Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

tmp95F5 TMP

Cargado por

FrontiersDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

tmp95F5 TMP

Cargado por

FrontiersCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Malaysian J Pathol 2013; 35(1) : 71 76

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Review of patients with Strongyloides stercoralis infestation in a

tertiary teaching hospital, Kelantan

AZIRA NMS,*,**ABDEL RAHMAN MZ* and ZEEHAIDA M*

*Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, and **Cluster of

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Abstract

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode infecting humans. The actual prevalence of

infestation with this parasite in our setting is not well established. Thus, this study was conducted

to determine the age, sex and co-morbid conditions among patients with S. stercoralis infestation as

well as to study the common manifestations of strongyloidiasis in our patients. Records of patients

with positive S. stercoralis larvae from January 2000 to December 2012 in Hospital Universiti Sains

Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan were reviewed. Ten patients were male and two were female.

Their ages ranged from 19 to 78 years old. The majority (92%) of cases, presented with intestinal

symptoms and 50% with moderate to severe anaemia. Thirty percent of cases had extraintestinal

manifestations such as cough, sepsis and pleural effusion. Ninety-two percent of the patients had

a comorbid illness. Most patients were immunocompromised, with underlying diabetes mellitus,

retroviral disease, lymphoma and steroid therapy contributing to about 58% of cases. Only 58%

were treated with anti-helminthic drugs. Strongyloidiasis is present in our local setting, though the

prevalence could be underestimated.

Key words: Strongyloides stercoralis, diarrhoea, abdominal discomfort

INTRODUCTION

Strongyloides stercoralis is a widespread, soiltransmitted intestinal helminth, which infects

millions of people worldwide.1 It was first

described in 1876 from stool specimens obtained

from soldiers who had returned from Vietnam and

were suffering from severe diarrhoea and other

gastrointestinal symptoms.2 Human infection

occurs in endemic areas when the infective

filariform larvae in contaminated soil actively

penetrate the intact skin of the feet sole or hand

palm; or the rhabditiform larva are ingested

with contaminated food.3 Low socioeconomic

backgrounds and habits that facilitate parasitic

transmission are known to be the major risk

factors for acquiring the primary infection.2,4

The disease is generally asymptomatic in an

immunocompetent person. It commonly manifests

as intestinal symptoms, frequently diarrhoea,

fever and abdominal pain. Some patients

present with cough, dyspnoea or constipation.5

Complications include autoinfection which may

lead to hyperinfection syndrome (HS) which is

a potentially serious life-threatening condition

in immunocompromised and immunosupressed

patients. 3 Generally, most of the patients

have underlying co-morbidities for instance

malnutrition, corticosteroid therapy, chronic

obstructive airway disease, chronic liver disease

or cirrhosis and peptic ulcer disease.5

The actual prevalence of infestation with this

parasite in our setting is not well identified. The

commonly associated risk factors for acquiring

this parasitic infestation include traveling into an

endemic area, working in the agriculture sector

and gardening as well as visiting contaminated

beaches.6

Current estimates indicate that at least 30-100

million people are infected with S. stercoralis

in 70 countries, and the risk for developing

advanced clinical complications is high in patients

with certain underlying clinical conditions.2,7

However, the present global estimation for the

prevalence of strongyloidiasis is not precise

and accurate, since the infection is sometimes

Address for correspondence and reprint requests: Dr. Nurul Azira Mohd Shah, Cluster of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

Universiti Teknologi Mara, 47000, Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia. Email: nazlizainuddin@yahoo.com

71

Malaysian J Pathol

misdiagnosed or difficult to detect because of the

poor sensitivity of the usual applied diagnostic

tests and the absence of reference standard (gold

standard) that provides an absolute evidence

for diagnosis.8,9 Therefore, S. stercoralis is

considered to be the most neglected among

soil-transmitted helminths infections.4

The disease has been studied among schoolage children10,11, travelers and immigrants,12,13

in tropical countries, 14 subjects with low

socioeconomic status and unhygienic habits,15-17

cancer patients,18 immunosuppressed patients,19

haematopoietic stem cell transplantation,19 and

in HTLV-1-infected patients.20 In addition, there

are case reports of acute, relapsed and fatal

strongyloidiasis.21-24

The occurrence of strongyloidiasis varies

widely among different countries, localities,

and socioeconomic backgrounds.6 The disease is

endemic in tropical, temperate and heavy rainfall

areas.3

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Southeast

Asia was determined as 11%.25 In Malaysia, the

prevalence of strongyloidasis among cancer

patients of all age groups who were treated with

various chemotherapeutic regimes was reported

as 5.7% (unpublished data). Rahmah et al.,16

had reported a prevalence of up to 1.2% among

aborigine children. The epidemiology of S.

stercoralis infection has been studied in much

more detail in Thailand, especially among school

children26 and was noted as 1.8%, this being 6-30

times greater than previous reports reported in

the same country.10

Infection with S. stercoralis is frequently

imported to non-endemic areas by travelers

and immigrants.27 In Spain, the epidemiology

of strongyloidiasis in the Mediterranean was

described as 0.9% among patients who were

elderly men and farmers who had walked

barefooted. 9 In the USA, 347 cases of

strongyloidiasis-associated deaths occurred

within a period of 15 years studied.28 In the

same country, it was found that half of cancer

patients who had strongyloidiasis had solid organ

malignancy and the remaining had haematologic

malignancy.18 Meanwhile in Columbia, 3.6% of

immunocompromised patients were found to be

infected with S. stercoralis.29

This study was conducted to determine the sex,

age, geographical area and co-morbid conditions

among patients with S. stercoralis infestation as

well as to study the clinical manifestations of

strongyloidiasis in our patients.

72

June 2013

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Records of patients with positive S. stercoralis

larvae from January 2000 to December

2012 in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia,

Kubang Kerian, Kelantan were reviewed. A

total of 15,155 of stool samples were received

within this study period. Single direct stool

microscopical examination was conducted. Wet

mount preparation of stool concentrate with

normal saline was done prior to microscopical

examination of the larvae. The morphology of the

larvae seen was described. Patients demographic

data such as age, sex, geographic area, co-morbid

conditions and clinical manifestations were

collected using a checklist. Data were analyzed

and presented as descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Only twelve cases were detected in 13-year

period from year 2000 to 2012. The overall

prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection

determined by the above method was 0.08%

(12/15,155). Ten patients (83.3%) were male

whereas two (16.7%) were female. Nine patients

were aged more than 60 years old while three

were less than 60. Most of the patients were

from Bachok (4), followed by Terengganu

(3), Kota Bharu (2), Pasir Putih (2) and Kuala

Lumpur (1).

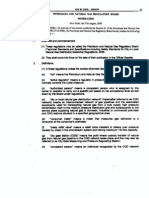

Ninety-two percent of the patients had

a co-morbid illness. Patients were mainly

immunocompromised patients, with underlying

diabetes mellitus (DM), retroviral disease,

lymphoma, chronic renal failure and steroid

therapy contributing 58% of cases (7 out of

12) (Figure 1). Concurrent illness such as

chronic obstructive airway disease (COAD),

hypertension (HPT) and chronic rheumatic heart

disease (CRHD) were also observed.

Our findings showed that most patients had

intestinal manifestations which were mainly

diarrhoea and abdominal discomfort (Table 1).

Less than half of the patients had extra-intestinal

manifestations. Twenty-five percent of patients

most probably had developed secondary bacterial

infections which lead to septicaemia.

Fifty-eight percent (7 out of 12) of patients

were treated with albendazole. In terms of

outcome, 11 patients survived while 1 died as

a result of secondary septicaemia.

STRONGYLOIDES STERCORALIS

Note: DM- Diabetes mellitus; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; COAD; Chronic Obstructive airway Disease;

HPT; Hypertensian;CRHD: Chronic Rheumatic Heart Disease, CRF; Chronic Renal Failure

FIG. 1: Percentage distribution of underlying co-morbidities in patients with Strongyloides stercoralis

infestation.

DISCUSSION

Strongyloides stercoralis is an important

intestinal helminthic infestation. It is endemic

mainly in rural areas in Malaysia but the actual

prevalence is not determined.

From our review of these strongyloidiasis

patients, males are more prone to infestation

compared to females. In our series, most of

the male patients were farmers. Male gender

has been attributed with higher prevalence

of strongyloidiasis. This could be due to

occupational exposure as most of the cases

reviewed here are farmers. In addition, the

cure rate of the infection in man is lower than

that in female, and this condition is marked by

the persistent elevation of serum IgG4.3,30 This

finding was reported in previous studies.9,7

Our centre is a referral centre for haematological

malignancies such as lymphoma and leukaemia

as well as solid organ cancers such as breast

cancer. In this review, the majority of patients

were immunocompromised. Although most

patients had intestinal symptoms, some

presented with extraintestinal symptoms such

as pleural effusion. Immunocompromised and

immunosuppressed conditions are identified as

common risks associated with this infestation

as well as contributing factors for developing

hyperinfection syndrome (HS). Autoinfection

can become amplified into a potentially fatal HS,

characterized by increased numbers of infective

filariform larvae in stool and sputum. Systemic

manifestations attributable to increase parasite

burden and migration, include gastrointestinal

bleeding and respiratory distress.3

TABLE 1: Clinical manifestations in patients with Strongyloides stercoralis infestation

Symptoms/ signs

Intestinal symptoms

Diarrhea

Constipation

Abdominal discomfort

Anorexia

Number (%)

11 (92)

9 (75)

1 ( 8)

7 (58)

5 (42)

Extraintestinal symptoms

Cough

Pleural effusion

Sepsis

4 (33)

2 (17)

2 (17)

3 (25)

Others

Moderate to severe anaemia

Fever

Weight loss

6 (50)

6 (50)

1 ( 8)

73

Malaysian J Pathol

In disseminated strongyloidiasis, bacteraemia

may develop as a result of translocation of

enteric bacteria through the tract created by

invading filariform larvae or bacteria itself can

be carried on the larva. This stage is found not

to be uncommon in the reviewed cases.3

There is no standard agreement on the

screening of S. stercoralis in suspected patients.

Routine diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is made

by a combination of stool direct microscopy,

concentration method, and culture method. Thus,

there are many reasons that can explain a very

low prevalence of strongyloidiasis among our

patients in this study. The diagnosis of chronic

strongyloidiasis from stool samples can be

difficult and insufficiently sensitive to be used

alone for screening because of intermittent larval

output in stool31,32 which lead to a low yield

of detection.33 The low sensitivity of routine

microscopical method may further contribute

to the low prevalence of detected infection.

In addition, the possibility of other unreported

cases may contribute to the overall low prevalence.

Most patients especially immunocompetent

patients are asymptomatic.33 Thus, such patients

were not presented to our setting.

On the other hand, the detection rate by direct

stool microscopy is found to be increased during

acute infection and hyperinfection as the result of

increased larval output as reported previously.34-36

However, it is extremely uncommon to see acute

infection or hyperinfection in routine clinical

practice or in surveys, since most of the positive

cases, if presented, are in the chronic phase

of the infection. Therefore, direct microscopy

alone is not useful in routine screening of

strongyloidiasis unless it is combined with other

detection methods or when the chronic disease

turns into active hyperinfection.6

The detection of parasitic DNA in faecal

samples using PCR-based methods proved

to be a sensitive and specific method for the

diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in individuals with

or without clinical symptoms at all infection

stages.37,38 Recent studies and case reports using

Strongyloides-real-time PCR reported increased

detection rates when compared with other stoolbased procedures.39 However, this method is not

widely available and is expensive, limiting its

use in developing countries.

Serological tests have shown a correlation

between S. stercoralis infection and antibody

level at all stages including acute, chronic,

hyperinfection, after treatment (treatment followup), and cure.6,40 In addition, serodiagnosis using

74

June 2013

ELISA appear to be useful in the diagnosis of

strongyloides infection in immunosuppressed

and immunocompetent patients.18 However,

there are some limitations for ELISA that may

affect results including: cross-reactions with

other nematode infections; variable sensitivity

and specificity; lack of a gold standard; and

inability to differentiate between acute or

chronic infections.2,41 In addition, the sensitivity

of serology is good in individuals with chronic

infection but is lower in those infected after

travelling to endemic areas.38,42

Albendazole is the preferred anti-helminthic

in this setting in view of its single dosing which

provides better compliance. Albendazole at

400 mg orally twice a day for 3 days has been

shown to clear stools of S. stercoralis larvae in

38% to 45% and normalize serology in 75% of

chronically infected individuals in whom larvae

were not detectable.3

As most of the reviewed cases were

immunocompromised patients, extra attention

should be made in providing screening tests to

those who are immunocompromised particularly

those presenting with symptoms of chronic

strongyloidisis, steroid therapy, diabetic, HIV

and patients with malignancy. This may help

in reducing the risk of hyperinfection and

disseminated strongyloidiasis. Screening of at

risk individiuals has also being suggested by

Keiser et al.3

In conclusion, Strongyloidiasis is present

in our local setting. However, as the current

available method which is microscopy has

low sensitivity, the actual prevalence of

strongyloidiasis might be underestimated. Thus,

other more sensitive methods such as molecular

methods may help in determining the actual

prevalence in this region. The infection should

be looked for especially in immunosuppressed

patients as its treatment would improve morbidity

and mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Nik Zairi

Zakaria and Mr. Zulnuhisham Suhaimi from

the Medical Microbiology and Parasitology

Laboratory, School of Medical Sciences,

Universiti Sains Malaysia for their technical

assistance.

REFERENCES

1. Weinstein D, Lake-Bakaar G. Strongyloides

stercoralis infection presenting with severe

STRONGYLOIDES STERCORALIS

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

malabsorption and arthritis in an immune competent

host. Internet J Rheumatology. 2006; 2(2). doi:

10.5880/13e9.

Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides

stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 33(7):

1040-7.

Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis

in the immunocompromised population. Clin

Microbiol Rev. 2004; 17(1): 208-17.

Olsen A, van Lieshout L, Marti H, et al.

Strongyloidiasis - the most neglected of the

neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med

Hyg. 2009; 103(10): 967-72.

Tsai HC, Lee SS, Liu YC, et al. Clinical

manifestations of strongyloidiasis in southern

Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2002; 35(1):

29-36.

Marcos LA, Terashima A, Dupont HL, Gotuzzo

E. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an

emerging global infectious disease. Trans R Soc

Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 102(4): 314-8.

Yori PP, Kosek M, Gilman RH, et al. Seroepidemiology

of strongyloidiasis in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J

Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 74(1): 97-102.

Lindo JF, Lee MG. Strongyloides stercoralis and S.

fulleborni. In: Gillespie SH, Pearson RD, editors.

Principles and practice of clinical parasitology. 1st

ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. p. 47992.

Snchez PR, Guzman AP, Guillen SM, et al. Endemic

strongyloidiasis on the Spanish Mediterranean coast.

QJM. 2001; 94(7): 357-63.

Anantaphruti MT, Nuamtanong S, Muennoo

C, Sanguankiat S, Pubampen S. Strongyloides

stercoralis infection and chronological changes of

other soil-transmitted helminthiases in an endemic

area of southern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop

Med Public Health. 2000; 31(2): 378-82.

Dada-Adegbola HO, Bakare RA. Strongyloidiasis

in children five years and below. West Afr J Med.

2004; 23(3): 194-7.

Loutfy MR, Wilson M, Keystone JS, Kain KC.

Serology and eosinophil count in the diagnosis and

management of strongyloidiasis in a non-endemic

area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002; 66(6): 749-52.

Sudarshi S, Stmpfle R, Armstrong M, et al.

Clinical presentation and diagnostic sensitivity

of laboratory tests for Strongyloides stercoralis

in travellers compared with immigrants in a nonendemic country. Trop Med Int Health. 2003; 8(8):

728-32.

Vannachone B, Kobayashi J, Nambanya S, Manivong

K, Inthakone S, Sato Y. An epidemiological survey

on intestinal parasite infection in Khammouane

Province, Lao PDR, with special reference to

Strongyloides infection. Southeast Asian J Trop

Med Public Health. 1998; 29(4): 717-22.

Huminer D, Symon K, Groskopf I, et al.

Seroepidemiologic study of toxocariasis and

strongyloidiasis in institutionalized mentally

retarded adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992; 46(3):

278-81.

Rahmah N, Ariff RH, Abdullah B, Shariman MS,

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

Nazli MZ, Rizal MZ. Parasitic infections among

aborigine children at Post Brooke, Kelantan,

Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 1997; 52(4): 412-5.

Machado ER, Teixeira EM, de Paula FM,

Gonalves-Pires MRF, Ueta MT, Costa-Cruz JM.

Immunoparasitological diagnosis of Strongyloides

stercoralis in garbage collectors in Uberlndia, MQ

Brazil. Parasitol Latinoam. 2007; 62(3-4): 180-2.

Safdar A, Malathum K, Rodriguez SJ, Husni

R, Rolston KV. Strongyloidiasis in patients at a

comprehensive cancer center in the United States.

Cancer. 2004; 100(7): 1531-6.

Schaffel R, Nucci M, Carvalho E, et al. The

value of an immunoenzymatic test (enzymelinked immunosorbent assay) for the diagnosis of

strongyloidiasis in patients immunosuppressed by

hematologic malignancies. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2001; 65(4): 346-50.

Hirata T, Uchima N, Kishimoto K, et al. Impairment

of host immune response against strongyloides

stercoralis by human T cell lymphotropic virus

type 1 infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 74(2):

246-9.

Abdelrahman MZ, Zeehaida M, Rahmah N,

et al. Fatal septicemic shock associated with

Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a patient with

angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a case report

and literature review. Parasitol Int. 2012; 61(3):

508-11.

Norsarwany M, Abdelrahman Z, Rahmah N, et al.

Symptomatic chronic strongyloidiasis in children

following treatment for solid organ malignancies:

case reports and literature review. Trop Biomed.

2012; 29(3): 479-88.

Prendki V, Fenaux P, Durand R, Thellier M,

Bouchaud O. Strongyloidiasis in man 75 years after

initial exposure. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011; 17(5):

931-2.

Win TT, Sitiasma H, Zeehaida M. Strongyloides

stercoralis induced bilateral blood stained pleural

effusion in patient with recurrent Non-Hodgkin

lymphoma. Trop Biomed. 2011; 28(1), 64-7.

Genta RM. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis:

critical review with epidemiologic insights into the

prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis.

1989; 11(5): 755-67.

Steinmann P, Zhou XN, Du ZW, et al. Occurrence

of Strongyloides stercoralis in Yunnan Province,

China, and comparison of diagnostic methods. PLoS

Negl Trop Dis. 2007; 1(1): e75.

van Doorn HR, Koelewijn R, Hofwegen H, et

al. Use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

and dipstick assay for detection of Strongyloides

stercoralis infection in humans. J Clin Microbiol.

2007; 45(2): 438-42.

Croker C, Reporter R, Redelings M, Mascola L.

Strongyloidiasis-related deaths in the United States,

1991-2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010; 83(2):

422-6.

Botero JH, Castao A, Montoya MN, Ocampo

NE, Hurtado MI, Lopera MM. A preliminary

study of the prevalence of intestinal parasites in

immunocompromised patients with and without

75

Malaysian J Pathol

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

76

gastrointestinal manifestations. Rev Inst Med Trop

Sao Paulo. 2003; 45(4): 197-200.

Walzer PD, Milder JE, Banwell JG, Kilgore G,

Klein M, Parker R. Epidemiologic features of

Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic

area of the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

1982; 31(2): 313-9.

Marty FM. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome

and transplantation: a preventable, frequently fatal

infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009; 11(2): 97-9.

Wirk B, Wingard JR. Strongyloides stercoralis

hyperinfection in hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009; 11(2):

143-8.

Mora CS, Segami MI, Hidalgo JA. Strongyloides

stercoralis hyperinfection in systemic lupus

erythematosus and the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 36(3): 135-43.

Kia EB, Rahimi HR, Mirhendi H, et al. A

case of fatal strongyloidiasis in a patient with

chronic lymphocytic leukemia and molecular

characterization of the isolate. Korean J Parasitol.

2008; 46(4): 261-3.

Azira NM, Zeehaida M. Strongyloides stercoralis

hyperinfection in a diabetic patient: case report.

Trop Biomed. 2010; 27(1): 115-9.

Stewart DM, Ramanathan R, Mahanty S, Fedorko

DP, Janik JE, Morris JC. Disseminated Strongyloides

stercoralis infection in HTLV-1-associated adult

T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Acta Haematol. 2011;

126(2): 63-7.

ten Hove RJ, van Esbroeck M, Vervoort T, van

den Ende J, van Lieshout L, Verweij JJ. Molecular

diagnostics of intestinal parasites in returning

travellers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;

28(9): 1045-53.

Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, et al. Molecular

diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal

samples using real-time PCR. Trans R Soc Trop

Med Hyg. 2009; 103(4): 342-6.

Basuni M, Muhi J, Othman N, et al. A pentaplex realtime polymerase chain reaction assay for detection

of four species of soil-transmitted helminths. Am J

Trop Med Hyg. 2011; 84(2): 338-43.

Rodrigues RM, de Oliveira MC, Sopelete MC, et al.

IgG1, IgG4, and IgE antibody responses in human

strongyloidiasis by ELISA using Strongyloides ratti

saline extract as heterologous antigen. Parasitol Res.

2007; 101(5): 1209-14.

Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Hendel-Paterson BR,

et al. Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case

series and worldwide physicians-in-training survey.

Am J Med. 2007; 120(6): 545. e1-8.

Marcos LA, Terashima A, Canales M,

Gotuzzo E. Update on strongyloidiasis in the

immunocompromised host. Curr Infect Dis Rep.

2011; 13(1): 35-46.

June 2013

También podría gustarte

- tmp80F6 TMPDocumento24 páginastmp80F6 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpCE8C TMPDocumento19 páginastmpCE8C TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp3CAB TMPDocumento16 páginastmp3CAB TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmpa077 TMPDocumento15 páginasTmpa077 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF178 TMPDocumento15 páginastmpF178 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp6F0E TMPDocumento12 páginastmp6F0E TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpEFCC TMPDocumento6 páginastmpEFCC TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmp1a96 TMPDocumento80 páginasTmp1a96 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp72FE TMPDocumento8 páginastmp72FE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF407 TMPDocumento17 páginastmpF407 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF3B5 TMPDocumento15 páginastmpF3B5 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpE3C0 TMPDocumento17 páginastmpE3C0 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpE7E9 TMPDocumento14 páginastmpE7E9 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpFFE0 TMPDocumento6 páginastmpFFE0 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp6382 TMPDocumento8 páginastmp6382 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp60EF TMPDocumento20 páginastmp60EF TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpB1BE TMPDocumento9 páginastmpB1BE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpC30A TMPDocumento10 páginastmpC30A TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp8B94 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp8B94 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp998 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp998 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp3656 TMPDocumento14 páginastmp3656 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp37B8 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp37B8 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpD1FE TMPDocumento6 páginastmpD1FE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpC0A TMPDocumento9 páginastmpC0A TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp4B57 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp4B57 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp9D75 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp9D75 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp27C1 TMPDocumento5 páginastmp27C1 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp2F3F TMPDocumento10 páginastmp2F3F TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpA0D TMPDocumento9 páginastmpA0D TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmp75a7 TMPDocumento8 páginasTmp75a7 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Buffer System - Group 3Documento5 páginasBuffer System - Group 3Rameen QadirAún no hay calificaciones

- TATA PROJECTS LIMITED Tilting & Drum Transfer Unit Technical SpecificationDocumento6 páginasTATA PROJECTS LIMITED Tilting & Drum Transfer Unit Technical SpecificationSridhar VedulaAún no hay calificaciones

- AnimalDocumento3 páginasAnimalSyamiminajwa RizanAún no hay calificaciones

- Songs BookDocumento38 páginasSongs BookАнастасія ЯщукAún no hay calificaciones

- Waterways Summer 2013Documento76 páginasWaterways Summer 2013Waterways MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Rosen 48V 200AH LiFePo4 Battery-PowerwallDocumento5 páginasRosen 48V 200AH LiFePo4 Battery-Powerwallgihan_maAún no hay calificaciones

- Pra Ukp 1-1Documento34 páginasPra Ukp 1-1Evantius TariganAún no hay calificaciones

- Technical Standards PNGRBDocumento44 páginasTechnical Standards PNGRBRashid HussainAún no hay calificaciones

- Hazard Management in Contracts Guidelines: Petroleum Development Oman L.L.CDocumento13 páginasHazard Management in Contracts Guidelines: Petroleum Development Oman L.L.Csatish20ntrAún no hay calificaciones

- 2020-Botao NHS Gad Budget-RevisedDocumento5 páginas2020-Botao NHS Gad Budget-RevisedJoseph Caballero CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Epidemiology of Chlamydia Trachomatis InfectionsDocumento20 páginasEpidemiology of Chlamydia Trachomatis InfectionsAmbarAún no hay calificaciones

- Genome Browser ExerciseDocumento5 páginasGenome Browser ExerciseyukiAún no hay calificaciones

- Overtime Pay-DOLEDocumento1 páginaOvertime Pay-DOLEJun CanilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Art of Focused ConversationsDocumento8 páginasArt of Focused Conversationsparaggadhia100% (1)

- Ecological Solid Waste Management Survey at Barangay 41 BogtongDocumento3 páginasEcological Solid Waste Management Survey at Barangay 41 BogtongRab Baloloy100% (1)

- School and Community RelationsDocumento8 páginasSchool and Community RelationsWendell HernandezAún no hay calificaciones

- Vaccination List: Name Anti-Hbs Vaccine To GIVE Hepa-B (PHP 340/dose)Documento10 páginasVaccination List: Name Anti-Hbs Vaccine To GIVE Hepa-B (PHP 340/dose)Manuel Florido ZarsueloAún no hay calificaciones

- General EcologyDocumento152 páginasGeneral Ecologykidest100% (2)

- Life Skills Curriculum - Secondary 1Documento546 páginasLife Skills Curriculum - Secondary 1Jeff Zacker100% (2)

- The Hunters: Anthropologists' Misconceptions of the !Kung PeopleDocumento4 páginasThe Hunters: Anthropologists' Misconceptions of the !Kung PeopleSimba GlynAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 7 - Products, Services - Brands-Building Customer ValueDocumento48 páginasChapter 7 - Products, Services - Brands-Building Customer ValuexuetingAún no hay calificaciones

- Tinjauan Penjelasan General Consent Di Pendaftaran Rawat Inap Rs Medika Permata HijauDocumento6 páginasTinjauan Penjelasan General Consent Di Pendaftaran Rawat Inap Rs Medika Permata HijauAgnesthesiaAún no hay calificaciones

- MCPS FBA Form 2016Documento4 páginasMCPS FBA Form 2016Nzinga WardAún no hay calificaciones

- Mark-Recapture Lab: BIOL 3370LDocumento2 páginasMark-Recapture Lab: BIOL 3370Lapi-475993899Aún no hay calificaciones

- Soal I KUNCIDocumento4 páginasSoal I KUNCIAyie Sharma100% (1)

- ChoiDocumento19 páginasChoiLuciana RafaelAún no hay calificaciones

- Red Cabbage IndicatorDocumento2 páginasRed Cabbage IndicatorgadbloodAún no hay calificaciones

- S9S12HA32CLLDocumento1 páginaS9S12HA32CLLAutotronica CaxAún no hay calificaciones

- ADEC - Al Khalil International School 2016-2017Documento19 páginasADEC - Al Khalil International School 2016-2017Edarabia.comAún no hay calificaciones

- English Debate Competition 558b213e259d1Documento22 páginasEnglish Debate Competition 558b213e259d1Mutiara MaulinaAún no hay calificaciones