Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Corporate Governance

Cargado por

priyanka963Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Corporate Governance

Cargado por

priyanka963Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

Corporate Governance in IndiaThe 1956 Companies Act as well as other laws governing the functioning

of joint-stock companiesand protecting the investors rights built on this foundation. The beginning of

corporate developmentsin India were marked by the managing agency system that contributed to the

birth of dispersed equityownership but also gave rise to the practice of management enjoying control

rights disproportionatelygreater than their stock ownership. The turn towards socialism in the decades

after independencemarked by the 1951 Industries (Development and Regulation) Act as well as the

1956 IndustrialPolicy Resolution put in place a regime and culture of licensing, protection and

widespread red-tapethat bred corruption and stilted the growth of the corporate sector.The situation

grew from bad to worse in the following decades and corruption, nepotism andinefficiency became the

hallmarks of the Indian corporate sector. Exorbitant tax rates encouragedcreative accounting practices

and complicated emolument structures to beat the system. In the absenceof a developed stock market,

the three all-India development finance institutions (DFIs) theIndustrial Finance Corporation of India,

the Industrial Development Bank of India and the IndustrialCredit and Investment Corporation of India

together with the state financial corporations became themain providers of long-term credit to

companies. Along with the government owned mutual fund, theUnit Trust of India, they also held large

blocks of shares in the companies they lent to and invariablyhad representations in their boards.In this

respect, the corporate governance system resembled the bank-based German model wherethese

institutions could have played a big role in keeping their clients on the right track.Unfortunately, they

were themselves evaluated on the quantity rather than quality of their lending andthus had little

incentive for either proper credit appraisal or effective follow-up and monitoring.Borrowers therefore

routinely recouped their investment in a short period and then had little incentiveto either repay the

loans or run the business. Frequently they bled the company with impunity,siphoning off funds with the

DFI nominee directors mute spectators in their boards.This sordid but increasingly familiar process

usually continued till the companys net worth wascompletely eroded. This stage would come after the

company has defaulted on its loan obligations fora while, but this would be the stage where Indias

bankruptcy reorganization system driven by the1985 Sick Industrial Companies Act (SICA) would

consider it sick and refer it to the Board forIndustrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). As soon as

a company is registered with the BIFR itwins immediate protection from the creditors claims for at least

four years. Between 1987 and 1992BIFR took well over two years on an average to reach a decision,

after which period the delay hasroughly doubled. Very few companies have emerged successfully from

the BIFR and even for thosethat needed to be liquidated, the legal process takes over 10 years on

average, by which time theassets of the company are practically worthless. Protection of creditors

rights has therefore existedonly on paper in India. Given this situation, it is hardly surprising that banks,

flush with depositorsfunds routinely decide to lend only to blue chip companies and park their funds in

governmentsecurities.Financial disclosure norms in India have traditionally been superior to most Asian

countries thoughfell short of those in the USA and other advanced countries. Noncompliance with

disclosure normsand even the failure of auditors reports to conform to the law attract nominal fines

with hardly anypunitive action. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in India has not been known to

take actionagainst erring auditors.While the Companies Act provides clear instructions for maintaining

and updating share registers, inreality minority shareholders have often suffered from irregularities in

share transfers andregistrations deliberate or unintentional. Sometimes non-voting preferential shares

have been usedby promoters to channel funds and deprive minority shareholders of their dues. Minority

shareholdersCorporate Governance Page 9

10. have sometimes been defrauded by the management undertaking clandestine side deals with

theacquirers in the relatively scarce event of corporate takeovers and mergers.Boards of directors have

been largely ineffective in India in monitoring the actions of management.They are routinely packed

with friends and allies of the promoters and managers, in flagrant violationof the spirit of corporate law.

The nominee directors from the DFIs, who could and should haveplayed a particularly important role,

have usually been incompetent or unwilling to step up to the act.Consequently, the boards of directors

have largely functioned as rubber stamps of the management.For most of the post-Independence era

the Indian equity markets were not liquid or sophisticatedenough to exert effective control over the

companies. Listing requirements of exchanges enforcedsome transparency, but non-compliance was

neither rare nor acted upon. All in all therefore, minorityshareholders and creditors in India remained

effectively unprotected in spite of a plethora of laws inthe books.The years since liberalization have

witnessed wide-ranging changes in both laws and regulationsdriving corporate governance as well as

general consciousness about it. Perhaps the single mostimportant development in the field of corporate

governance and investor protection in India has beenthe establishment of the Securities and Exchange

Board of India (SEBI) in 1992 and its gradualempowerment since then. Established primarily to regulate

and monitor stock trading, it has played acrucial role in establishing the basic minimum ground rules of

corporate conduct in the country.Concerns about corporate governance in India were, however, largely

triggered by a spate of crises inthe early 90s the Harshad Mehta stock market scam of 1992 followed

by incidents of companiesallotting preferential shares to their promoters at deeply discounted prices as

well as those ofcompanies simply disappearing with investors money. These concerns about corporate

governancestemming from the corporate scandals as well as opening up to the forces of competition

andglobalization gave rise to several investigations into the ways to fix the corporate governance

situationin India. One of the first among such endeavours was the CII Code for Desirable

CorporateGovernance developed by a committee chaired by Rahul Bajaj. The committee was formed in

1996and submitted its code in April 1998. Later SEBI constituted two committees to look into the issue

ofcorporate governance the first chaired by Kumar Mangalam Birla that submitted its report in

early2000 and the second by Narayana Murthy three years later. The SEBI committee

recommendationshave had the maximum impact on changing the corporate governance situation in

India. The AdvisoryGroup on Corporate Governance of RBIs Standing Committee on International

Financial Standardsand Codes also submitted its own recommendations in 2001.Recommendations of

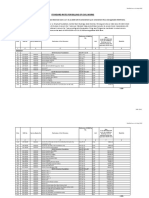

various committees on Corporate Governance in IndiaCII Code recommendations (1997) 1. No need for

German style two-tiered board. 2. For a listed company with turnover exceeding Rs 100 crores, if the

chairman is also the MD, at least half of the board should be independent directors, else at least 30%. 3.

No single person should hold directorships in more than 10 listed companies. 4. Non-executive directors

should be competent and active and have clearly defined responsibilities like in the Audit committee. 5.

Directors should be paid a commission not exceeding 1% (3%) of net profits for a company with (out) an

MD over and above sitting fees. Stock options may be considered too. 6. Attendance record of directors

should be made explicit at the time of re-appointment. Those with less than 50% attendance shouldnt

be re-appointed. 7. Key information that must be presented to the board is listed in the code. 8. Audit

Committee: Listed companies with turnover over Rs. 100 crores or paid-up capital of Rs. 20 crores

should have an audit committee of at least three members, all non-executive, competent and willing to

work more than other non-executive directors, with clear terms of reference and access to all financial

information in the company and should periodicallyCorporate Governance Page 10

11. interact with statutory auditors and internal auditors and assist the board in corporate accounting

and reporting. 9. Reduction in number of nominee directors. FIs should withdraw nominee directors

from companies with individual FI shareholding below 5% or total FI holding below 10%.Birla Committee

(SEBI) recommendations (2000) 1. At least 50% non-executive members. 2. For a company with an

executive Chairman, at least half of the board should be independent directors, else at least one-third.

3. Non-executive Chairman should have an office and be paid for job related expenses. 4. Maximum of

10 directorships and 5 chairmanships per person. 5. Audit Committee: A board must have a qualified

and independent audit committee, of minimum 3 members, all non-executive, majority and chair

independent with at least one having financial and accounting knowledge. Its chairman should attend

AGM to answer shareholder queries. The committee should confer with key executives as necessary and

the company secretary should be he secretary of the committee. The committee should meet at least

thrice a year -- one before finalization of annual accounts and one necessarily every six months with the

quorum being the higher of two members or one-third of members with at least two independent

directors. It should have access to information from any employee and can investigate any matter within

its TOR, can seek outside legal/professional service as well as secure attendance of outside experts in

meetings. It should act as the bridge between the board, statutory auditors and internal auditors with

arranging powers and responsibilities. 6. Remuneration Committee: The remuneration committee

should decide remuneration packages for executive directors. It should have at least 3 directors, all

Nonexecutive and be chaired by an independent director. 7. The board should decide on the

remuneration of non-executive directors and all remuneration information should be disclosed in annual

report. 8. At least 4 board meetings a year with a maximum gap of 4 months between any 2 meetings.

Minimum information available to boards stipulated.Narayana Murthy committee (SEBI)

recommendations (2003) 1. Training of board members suggested. 2. There shall be no nominee

directors. All directors to be elected by shareholders with same responsibilities and accountabilities. 3.

Non-executive director compensation to be fixed by board and ratified by shareholders and reported.

Stock options should be vested at least a year after their retirement. Independent directors should be

treated the same way as non-executive directors. 4. The board should be informed every quarter of

business risk and risk management strategies. 5. Boards of subsidiaries should follow similar

composition rules as that of parent and should have at least one independent directors of the parent

company. 6. The Board report of a parent company should have access to minutes of board meeting in

subsidiaries and should affirm reviewing its affairs. 7. Performance evaluation of non-executive directors

by all his fellow Board members should inform a re-appointment decision. 8. While independent and

non-executive directors should enjoy some protection from civil and criminal litigation, they may be held

responsible of the legal compliance in the companys affairs. 9. Code of conduct for Board members and

senior management and annual affirmation of compliance to it.Corporate Governance Page 11

12. Weaknesses of Corporate Governance In IndiaThe Satyam debacle has exposed the chinks in Indian

corporate governance mechanism and themonitoring authorities. It has raised many questions about

corporate governance in Indiathe role ofboards, of independent directors, of the auditors, of investors

and of analysts. Unanimously it has beena gross failure of corporate governance standards in India and

protection of rights of minorityinvestors.The board of directors is central to good governance, and the

role of the board has featuredprominently in discussions about Satyam. The board is the body charged

with having oversight of theoperations of the firm and setting its strategy. It should ensure that the

company is upholding highstandards of probity and conduct, and provide a probing analysis of the

activities of management. Inparticular, non-executive directors are supposed to give an independent

assessment of the quality ofmanagement. But time and time again, failures of corporate governance

suggest that they do not. Theinfractions of law have arisen despite independent directors which were

stopped by external forces.There are several reasons pointing to these anomalies-First, it is difficult to

appoint truly independent directors. This is particularly hard to achieve incountries such as India where

family ownership is widespread and there is a close-knit group ofcorporate leaders. It is difficult for non-

executive directors to perform a scrutiny objective at the bestof times, but it is particularly difficult to do

so when faced with a dominant CEO who expects supportnot criticism from the companys board. Many

countries have sought to separate the roles of chairmanand CEO. However, it can inhibit firms from

implementing effective strategies, especially incompanies operating with new technologies, such as

Indian IT/ITES firms, requiring visionarystrategies.Next, the very idea of independent directors is to

ensure commitment to values, ethical businessconduct and about making a distinction between

personal and corporate funds in the management of acompany. Yet, most independent directors have

become sidekicks for the management, eying theircommission and fees, forgetting their very purpose of

appointment. In the process, they implicitlytransform into dependent directors.To add to that the

present corporate governance modelled on the Western Anglo-Saxon model whichdoes not address

many of the current crises faced by India Inc. Professor Jayant Rama Verma of IIMBangalore had

extensively commented on the unsuitability of the Western Code of CorporateGovernance in his well

researched paper on the subject titled Corporate Governance in India -Disciplining the dominant

shareholder (1997):According to him, the governance issue in the Anglo-Saxon world aims essentially at

disciplining themanagement which is unaccountable to the owners. In contrast, the problem in the

Indian corporatesector, he pointed out, is disciplining the dominant shareholder and protecting the

minorityshareholders, vindicated in the recent Satyam case. To understand the issues that driving

corporategovernance in the West, a brief idea about it is inevitable. After successfully working over

thedecades separating ownership and management, owners, (especially, institutional owners)

realisedthat they have lost control over the management or the board. Professor Verma points out

succinctly,"The management becomes self-perpetuating and the composition of the board itself is

largelyinfluenced by the whims of the CEO. Corporate governance reforms in the US and the UK

havefocussed on making the board independent of the CEO.In contrast, the issues in India are entirely

distinct - primarily due to our overall social-economicconditions. Therefore the issue in Indian corporate

governance is not a conflict between managementand owners as elsewhere, but a conflict between the

dominant shareholders and the minorityshareholders. And Professor Verma rightly concludes, "The

board cannot even in theory resolve thisconflict" and that "some of the most glaring abuses of corporate

governance in India have beenCorporate Governance Page 12

13. defended on the principle of shareholder democracy since they have been sanctioned by resolutions

ofthe general body of shareholders."By now it is increasingly obvious that the very concept of corporate

governance modelled on theWestern system is un-workable in a country like India. These efforts are

akin to taking a hair of anelephant, transplanting it on the head of a bald man and making him look like a

bear. In the West thefocus is on ownerless, CEO-driven paradigm. In India, it is still family-controlled,

owner-drivenparadigm. CEOs do not matter much in the management of the company. Yet, the general

discussioncentres on a standard, global prescription to manage diverse situations. Needless to

emphasise, thesolution to these problems in India lies not within the company, but outside. This is

precisely whathappened in the Satyam case where outsiders of the company took the lid off the fraud.In

spite of numerous suggestions by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), for peerreviews of

audits among the companies listed in the Nifty and Sensex indices they have fallen flat onthe industry

fraternity. Presumably, SEBI will allocate the audits to firms that are part of a panel ofreputed auditors.

The simple solution would be for the regulator to make this course of actionmandatoryauditors could

be allotted audits by the regulator. To avoid the allegations ofoverregulation, companies can submit a

list of their preferred auditors, from which the regulator willhave to choose. Audits could also be rotated

annually, keeping them on their toes. And these samerules could also be applied to rating agencies,

internal auditors, independent directors etc. From timeto time these mechanisms can be fine-tuned and

made more practical.The moot question is why these reformative suggestions have not been

implemented? The answer isthat it depends on whos got more lobbying power. In the US, the large

pension funds that have beeninstrumental in getting more transparency from company managements.

India, on the other hand, hasno tradition of shareholder activism, despite organisations such as the Life

Insurance Corporation ofIndia having substantial stakes in companies. The dependence of political

parties on business intereststo fund elections also doesnt help. The failure of governments and

regulators to pass what seems likevery basic safeguards preventing conflicts of interest, not only in

India, but across the world, clearlyestablishes the clout that corporate interests have. Corporate

governance is thus a charade, a cosmeticexercise rather than an attempt to get to the root of the

problem.Of course, too rigid a focus on the stock market also has its own set of problems. As

SatyamComputer Services Ltds founder B. Ramalinga Raju said in his confession, the apparent reason

whyhe inflated earnings was because he feared that bad results would lead to a fall in the stock and

atakeover attempt. We neednt take Rajus word for it, but the fact remains that too much of a focus

onquarterly earnings and the linking of executive compensation with the stock market via stock

optionscould act as powerful incentives for inflating earnings.Corporate Governance Page 13

14. Recommendations to Implement Corporate GovernanceAfter a slew of scandals, politicians and

regulators, executives and shareholders are all preaching thegovernance gospel. Corporate governance

has come to dominate the political and business agenda.There is a growing concern among executives

that hasty regulation and overly strict internalprocedures may impair their ability to run their business

effectively. CEOs have to bear in mind thepotential trade-off between polishing the corporate

reputation and delivering growthfor all theheadlines on corporate responsibility, are investors

prepared consistently to sacrifice earnings for thesake of ethics?Regulations are only one part of the

answer to improved governance. Corporate governance is abouthow companies are directed and

controlled. The balance sheet is an output of manifold structural andstrategic decisions across the entire

company, from stock options to risk management structures, fromthe composition of the board of

directors to the decentralisation of decision-making powers. As aresult, the prime responsibility for good

governance must lie within the company rather than outsideit.A key lesson from the Enron experience,

where the board was an exemplar of best practice on paper,is that governance structures count for little

if the culture isnt right. Designing and implementingcorporate governance structures are important, but

instilling the right culture is essential. Seniormanagers need to set the agenda in this area, not least in

ensuring that board members feel free toengage in open and meaningful debate. Not all board

members need to be finance or risk experts,however. The primary task for the board is to understand

and approve both the risk appetite of aparticular company at any particular stage in its evolution and

the processes that are in place tomonitor risk.Culture is necessary but not sufficient to ensure good

corporate governance. The right structures,policies and processes must also be in place. Transparency

about a companys governance policies iscritical. As long as investors and shareholders are given clear

and accessible information about thesepolicies, the market can be allowed to do the rest, assigning an

appropriate risk premium to companiesthat have too few independent directors or an overly aggressive

compensation policy, or cutting thecosts of capital for companies that adhere to conservative

accounting policies. Too few companies aregenuinely transparent, however, and this is an area where

most organisations can and should do muchmore.If any institution, inside or outside the company,

deserves scrutiny, it is the board of directors.Executives have a clear responsibility consciously to define

and implement corporate governancepolicies that offer a decent level of reassurance to employees and

investors. Thereafter, disclosure isthe most effective way for companies to resolve the thorny tensions

that do exist between vision andprudence, innovation and accountability.There is an inherent tension

between innovation and conservatism, governance and growth. Asked toevaluate the impact of strict

corporate governance policies on their business, executives thought thatM&A deals would be negatively

affected because of the lengthening of due-diligence procedures, andthat the ability to take swift and

effective decisions would be compromised. State-of-the-art corporategovernance can bring benefits to

companies, to be sure, but also introduces impediments to growth.Some procedures and processes that

companies can implement to enhance corporate governance aredetailed as follows.Scheduling regular

meetings of the non-executive board members from which other executives areexcluded. Non-

executives are there to exercise constructive dissatisfaction with the managementteam. They need

to discuss collectively and frankly their views about the performance of theCorporate Governance Page

14

15. executives, the strategic direction of the company and worries about areas where they

feelinadequately briefed.Explaining fully how discretion has been exercised in compiling the earnings

and profit figures. Theseare not as cut and dried as many would imagine. Assets such as brands are

intangible and withfinancial practices such as leasing common, a lot of subtle judgments must be made

about what goeson or off the balance sheet. Use disclosure to win trust.Initiating a risk-appetite review

among non-executives. At the root of most company failures are ill-judged management decisions on

risk. Non-executives need not be risk experts. But it is paramountthat they understand what the

companys appetite for risk isand accept, or reject, any radical shifts.Checking that non-executive

directors are independent. Weed out members of the controlling familyor former employees who still

have links to people in the company. Also raise awareness of softconflicts. Are there payments or

privileges such as consultancy contracts, payments to favouritecharities or sponsorship of arts events

that impair non-executives ability to rock the boat?Auditing non-executives performance and that of

the board. The attendance record of nonexecutivesneeds to be discussed and an appraisal made of the

range of specialist skills. The board should discussannually how well it has performed.Broadening and

deepening disclosure on corporate websites and in annual reports. Websites shouldhave a corporate

governance section containing information such as procedures for getting a motioninto a proxy ballot.

The level of detail should ideally include the attendance record of non-executivesat board

meetings.Leading by example, reining in a company culture that excuses cheating. If the company

culture hasbeen compromised, or if one is in an industry where loose practices on booking revenues

andexpenditure are sometimes tolerated, take a few high-profile decisions that signal change.Finding a

place for the grey and cautious employee alongside the youthful and visionary one. Hiringthrusting

graduates will skew the culture towards an aggressive, individualist outlook. Balance thiswith some

wiser, if duller headspeople who have seen booms and busts before, value probity andare not in so

much of a hurry. Making compensation committees independent. Corporate bossesshould be prevented

from selling shares in their firms while they head them. Share options should beexpensed in established

companiescash-starved start-ups may need to be more flexible.Corporate governance is not just a box

ticking exercise, companies need an exchange of practicalguidance in order to conceive and implement

successful governance mechanism. Instead of a menu ofcorporate governance options it would be more

appropriate to present best practice guidelinesapplicable to businesses. These will serve as a benchmark

for appropriate customization in differentcompanies. Corporate governance should be considered as an

obligation not a luxury. Its spirit isgoing to expand further and deeper in the future.Corporate

Governance

También podría gustarte

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Industrial Tour Report (JEWEL - MANAGEMENT-CU)Documento37 páginasIndustrial Tour Report (JEWEL - MANAGEMENT-CU)Mohammad Jewel100% (2)

- Student Name Student Number Assessment Title Module Title Module Code Module Coordinator Tutor (If Applicable)Documento32 páginasStudent Name Student Number Assessment Title Module Title Module Code Module Coordinator Tutor (If Applicable)Exelligent Academic SolutionsAún no hay calificaciones

- Delhi Metro Rail Corporation LTD Jr. Engineer Results PDFDocumento3 páginasDelhi Metro Rail Corporation LTD Jr. Engineer Results PDFedujobnewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter Three Business PlanDocumento14 páginasChapter Three Business PlanBethelhem YetwaleAún no hay calificaciones

- ArraysDocumento36 páginasArraysKAMBAULAYA NKANDAAún no hay calificaciones

- @airbus: Component Maintenance Manual With Illustrated Part ListDocumento458 páginas@airbus: Component Maintenance Manual With Illustrated Part Listjoker hotAún no hay calificaciones

- Uuee 17-2020Documento135 páginasUuee 17-2020Tweed3AAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Titan Watch IndustryDocumento46 páginasHistory of Titan Watch IndustryWasim Khan25% (4)

- Ceramic Disc Brakes: Haneesh James S ME8 Roll No: 20Documento23 páginasCeramic Disc Brakes: Haneesh James S ME8 Roll No: 20Anil GöwđaAún no hay calificaciones

- ERACS JournalDocumento8 páginasERACS Journalmahasiswaprofesi2019Aún no hay calificaciones

- PROFILITE 60 EC Suspended 09 130 3001-01-830 Product Datasheet enDocumento4 páginasPROFILITE 60 EC Suspended 09 130 3001-01-830 Product Datasheet enGabor ZeleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Only PandasDocumento8 páginasOnly PandasJyotirmay SahuAún no hay calificaciones

- Container Stowage Plans ExplainedDocumento24 páginasContainer Stowage Plans ExplainedMohd akifAún no hay calificaciones

- Masonry Design and DetailingDocumento21 páginasMasonry Design and DetailingKIMBERLY ARGEÑALAún no hay calificaciones

- Netflix AccountsDocumento2 páginasNetflix AccountsjzefjbjeAún no hay calificaciones

- Project ProposalDocumento6 páginasProject Proposalapi-386094460Aún no hay calificaciones

- A New High Drive Class-AB FVF Based Second Generation Voltage ConveyorDocumento5 páginasA New High Drive Class-AB FVF Based Second Generation Voltage ConveyorShwetaGautamAún no hay calificaciones

- Concepts in Enterprise Resource Planning: Chapter Six Human Resources Processes With ERPDocumento39 páginasConcepts in Enterprise Resource Planning: Chapter Six Human Resources Processes With ERPasadnawazAún no hay calificaciones

- AcctIS10E - Ch04 - CE - PART 1 - FOR CLASSDocumento32 páginasAcctIS10E - Ch04 - CE - PART 1 - FOR CLASSLance CaveAún no hay calificaciones

- CAT Álogo de Peças de Reposi ÇÃO: Trator 6125JDocumento636 páginasCAT Álogo de Peças de Reposi ÇÃO: Trator 6125Jmussi oficinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cryogenics 50 (2010) Editorial on 2009 Space Cryogenics WorkshopDocumento1 páginaCryogenics 50 (2010) Editorial on 2009 Space Cryogenics WorkshopsureshjeevaAún no hay calificaciones

- Rift Valley University Office of The Registrar Registration SlipDocumento2 páginasRift Valley University Office of The Registrar Registration SlipHACHALU FAYEAún no hay calificaciones

- Mining Operational ExcellenceDocumento12 páginasMining Operational ExcellencegarozoAún no hay calificaciones

- Identifying Social Engineering Attacks - Read World ScenarioDocumento4 páginasIdentifying Social Engineering Attacks - Read World Scenarioceleste jonesAún no hay calificaciones

- HE Vibration AnalysisDocumento8 páginasHE Vibration AnalysisWade ColemanAún no hay calificaciones

- Stahl Cable Festoon SystemsDocumento24 páginasStahl Cable Festoon SystemsDaniel SherwinAún no hay calificaciones

- House Bill 470Documento9 páginasHouse Bill 470Steven DoyleAún no hay calificaciones

- Tough Turkish TBM Moves Through Fractured and Faulted Rock: Issue 1 + 2014Documento8 páginasTough Turkish TBM Moves Through Fractured and Faulted Rock: Issue 1 + 2014sCoRPion_trAún no hay calificaciones

- Final ThoughtDocumento6 páginasFinal ThoughtHaroon HussainAún no hay calificaciones

- SMB GistDocumento7 páginasSMB GistN. R. BhartiAún no hay calificaciones