Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Tet Offensive

Cargado por

Graciela RapDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Tet Offensive

Cargado por

Graciela RapCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1

Tet Offensive

Four-star General Vo Nguyen Giap led Vietnam's armies from their inception, in the 1940s, up to

the moment of their triumphant entrance into Saigon in 1975.

Possessing one of the finest military minds of this century, his strategy for vanquishing superior

opponents was not to simply outmaneuver them in the field but to undermine their resolve by

inflicting demoralizing political defeats with his bold tactics.

This was evidenced as early as 1944, when Giap sent his minuscule force against French outpost in

Indochina. The moment he chose to attack was Christmas Eve. More devastatingly, in 1954 at a

place called Dien Bien Phu, Giap lured the overconfident French into a turning point battle and

won a stunning victory with brilliant deployments. Always he showed a great talent for

approaching his enemy's strengths as if they were exploitable weaknesses.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, in 1968, the General launched a major surprise offensive

against American and South Vietnamese forces on the eve of the lunar New Year celebrations.

Province capitals throughout the country were seized, garrisons simultaneously attacked and,

perhaps most shockingly, in Saigon the U.S. Embassy was invaded. The cost in North Vietnamese

casualties was tremendous but the gambit produced a pivotal media disaster for the White House

and the presidency of Lyndon Johnson. Giap's strategy toppled the American commander in chief.

It turned the tide of the war and sealed the General's fame as the dominant military genius of the

20th Century's second half.

By John W. Flores

Twelve enemy soldiers, armed with B-40 rocket propelled grenades, moved stealthily through the

underbrush that lined the edge of the schoolyard of the Jeann d'Arc High School and Church

complex, located on the edge of Hue City. They took cover as 38-man U.S. Marine force

approached their position across an open field on the opposite side of the church. A violent and

bloody showdown was imminent.

It was the morning of February 4, 1968, five days after the NVA and VC had overrun Hue, the old

Imperial capital of Vietnam, at the beginning of their Tet Offensive. The Marines were from the

3rd Platoon, Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment (1/1), commanded by Sergeant

Alfredo "Freddy" Gonzalez, a 21 year-old Marine from Edinburg, Texas. He had taken charge

2

several days earlier after the lieutenant who normally commanded the platoon had been

wounded and evacuated.

Gonzalez had enlisted in the Marines three years earlier, in May 1965, just after graduating from

high school. He had always wanted to be a Marine from the time he was a small boy, according to

his mother, Dolia Gonzalez, who still lives in Edinburg. Often, while watching John Wayne war

movies at the town theater on Saturday afternoons, he would nudge his mother, cup his hand to

her ear and whisper, "Someday I'm going to be a Marine just like that."

After boot camp, Gonzalez served a one-year tour in Vietnam in 1966-67. "Freddy had just

completed one tour of duty, and he'd made it back home," recalled J.J. Avila, a close friend of

Gonzalez's who also served as a Marine in Vietnam. "He was on leave, and I remember he called

me over to his house and said he had had a serious dilemma. He had just gotten word that a

platoon of men he had served with in Vietnam had been blown away in an ambush." Gonzalez told

Avila he believed that he could have kept the men alive had he been at the scene. "And he had

reason to be so confident," said Avila. "He saved many men through his coolness under fire, a

calculating, rapid-fire courage, and a big-brother's concern for his men." Avila continued: "I told

Freddy, "Do not go back. You've done your duty." He said he did not want to go back. He's seen

enough of the war, and he wanted to be close to home to take care of his mother. But the ambush

really hit him hard. Finally, I knew it was no use. He'd made up his mind, and there was no

changing it. I told him he'd already done his duty, but if he had to go back, just be careful. Just

come back home."

When Gonzalez returned to Vietnam he was assigned to Alpha Company, 1/1. In January 1968 the

men had just come off duty along the DMZ at Con Thien and had moved south to the provincial

capital at Quang Tri. "I had no other officers with me," recalled retired Marine Colonel Gordon

Batcheller, who then a captain had taken command of Alpha Company on Christmas Day 1967.

"They were all gone. Sergeant Gonzalez was commander of the 3rd Platoon. We were ordered as

part of a large-scale movement down to Phu Bai, outside of Hue, the night before the Tet

Offensive started on January 30. We were alerted we would be a reaction force, then I got blown

away with an automatic weapon of some kind going into Hue and was medevaced out."

Lieutenant (now Maj. Gen.) Ray Smith, who took command of Alpha Company after Batcheller was

wounded, was impressed with platoon leader Gonzalez. "The thing that probably is most

surprising and maybe says a lot about him is that I thought of Sergeant Gonzalez as an old

veteran," said Smith, "At the time, I mean, I remember thinking of Sergeant Gonzalez as an old-

timer, a guy who had been around a while. I was just 21, and as it turned out he was four or five

months younger than me. I remember him as a real mature, grown-up sergeant type of a guy, as

3

opposed to the 21 year-old that he was. He was a real quite person, but he always had a smile on

his face. He was a little restrained in his emotions, but that was probably because he was truly one

of the 'grown-ups' in our organization."

"I primarily knew him on a personal basis, because in November and December 1967 in Quang Tri

we had an officer and staff NCO card game," continued Smith. "We would gather in the company

commander's bunker and play penny ante poker. You had to be an officer or a staff NCO to be

involved in that card game, but we made an exception for Gonzalez because he was to us a grown-

up among those kids. Like a lot of people that you remember for their actions, my memory of him

is as a big muscular guy. He was actually fairly small. I'm 6'feet-2" inches tall and 218 pounds.

Recently a friend sent me a photo of Sergeant Gonzalez and I standing beside each other. I

couldn't believe I was that much bigger than him. It was just the opposite in my memory. He was

the big one"

During the advance into Hue City, Gonzalez was wounded twice by machine-gun and mortar fire.

At one point, when Gonzalez and other Marines became targets of sniper fire, they took cover

behind an armoured vehicle that was rolling along ahead of the platoon. One of the privates under

Gonzalez's command was hit and went down on the road ahead. Gonzalez jumped from behind

the tank and sprayed fire at a VC machine-gun bunker that was hidden amid the heavy foliage

along the dirt road. While some members of his platoon were momentary stunned by Gonzalez's

bold move, others raked the machine-gun nest with automatic-weapons fire. Before the sergeant

reached the badly wounded Marine 20 or 30 yards ahead, he made his way along a narrow ditch

until he was near the bunker. He then lobbed two grenades inside, and the explosions killed the

enemy soldiers in the bunker. Gonzalez then made his way back to the wounded private, heaved

his 170-pound body over his shoulder and ran back towards the cover of the tank. Although hit by

bullet fragments and mortar shrapnel from other enemy troops and bleeding badly, Gonzalez

managed to reach the tank.

A Navy corpsman rushed to administer to Gonzalez and the dying Marine he had tried to save and

ordered the sergeant to leave by medevac chopper. But Gonzalez would have none of it, according

to Smith. These were his men, and he refused to leave them. As Gonzalez's boss, Smith tried to get

another sergeant to take command of the 3rd Platoon while the company continued its advance

on Hue City. But nobody challenged Gonzalez's decision to fight on. According to Smith, "The

gunnery sergeant said, "Lieutenant, I'll go and follow Sergeant Gonzalez around if you want me to,

but he is in command of 3rd Platoon." He said he was going to put him in for the Medal of Honor if

we survived. Always seen as a good solid, lead-by example Marine, when we entered the fight in

Hue City, Gonzalez became way more than that. for the next few days he became almost a one-

man army. All of us who survived remain in awe of him."

4

On February 4, 1968, as smith later recalled, "the first objective of the company was the St. Joan of

Arc School and church only about 100 yards away." It was a key position that both sides wanted

because it could serve as a protective bulwark during the fighting. "The building was square, with

an open compound in the middle," recalled Smith, "and we found that by 0700 hours it was

heavily occupied." Sergeant Gonzalez ordered his platoon to keep down, out of the line of fire,

while he surveyed the situation. Meanwhile Lieutenant Smith and the remainder of Alpha

Company entered the school.

Suddenly a fire storm erupted. Many of the Marines fell dead or wounded from machine-gun and

rocket fire, and platoons from scattering like pool balls after a break, with bullets whizzing inches

above the men's helmets. Only a handful were already inside the church and school corridors, and

those who had fanned out to take cover were under intense fire. "We were trying to secure the

church," said Smith, "and the enemy was inside the school. We had to blow holes in the walls so

we could get through and take the school rooms. It was very tough fighting." Smith's Marines

found themselves engaged in room-to-room combat.

Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Gravel, the battalion commander of the 1/1, said that in the convent

building the Marines proceeded from wall to wall. "One Marine would place a plastic C-4 charge

against the wall, stand back, and then a fire team would rush through the gaping hole. In the

school building Sergeant Gonzalez's 3rd Platoon secured one wing but came under enemy rocket

fire from across the courtyard." Although still suffering from his earlier wounds, Sergeant Gonzalez

managed to grab a handful of LAW's (M-72 light antitank weapons) and positioned himself on the

second floor of the school, firing at enemy positions from one window to another," said Smith. "He

had managed to take out several of the enemy positions when a rocket was fired at him and hit

him in the midsection."

Lawrence "Little Larry" Lewis of Chattanooga, Tenn., a rifleman in Gonzalez platoon, was only a

few feet away from the sergeant when he was hit. Lewis had arrived in Vietnam in September

1967 and was terribly frightened he would be killed. Sergeant Gonzalez had noticed that he was

upset and had talked to the young man and put him at ease. When Gonzalez went down, Lewis

pulled him out of the line of fire and laid him on a door. "His heart was still beating," Lewis

recalled, "but he was died a short time later. O couldn't believe he was hit. He was hero to us all,

and took care of us young guys when we got in country."

Gonzalez was a hero to his country as well. In 1969, his mother Dolia Gonzalez, was escorted to

the White House to receive the Medal of Honor awarded to her son posthumously. Signed by

President Richard Nixon and presented by Vice President Spiro Agnew, the official citation read:

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty

while serving as Platoon Commander, Third Platoon, Company A, First Battalion, first marines, first

5

Marine Division, in the Republic of Vietnam. On 31 January 1968, during the initial phase of

Operation Hue City, Sergeant Gonzalez's unit was formed as a reaction force and deployed to Hue

to relieve the pressures on the beleaguered city. While moving by truck convoy along Route #1,

near the village of Lang Van Long, the Marines received a heavy volume of enemy fire. Sergeant

Gonzalez aggressively maneuvered the Marines in his platoon, and directed their fire until the area

was cleared of snipers. Immediately after crossing a river south of Hue, the column was again hit

by intense enemy fire. One of the Marines on top of a tank was wounded and fell to the ground in

an exposed position. With complete disregard for his own safety, Sergeant Gonzalez ran through

the fire-swept area to the assistance of his injured comrade. He lifted him up and though receiving

fragmentation wounds during the rescue, he carried the wounded Marine to a covered position

for treatment. Due to the increased volume and accuracy of enemy fire from fortified machine-

gun bunker on the other side of the road, the company was temporarily halted. Realizing the

gravity of the situation, Sergeant Gonzalez exposed himself to the enemy fire and moved his

platoon along the East side of a bordering rice paddy to a dike directly from the bunker. Though

fully aware of the danger involved, he moved to the fire-swept road and destroyed the hostile

position with hand grenades. Although seriously wounded again on 3 February, the enemy had

again pinned the company down, inflicting heavy casualties with automatic weapons and rocket

fire. Sergeant Gonzalez, utilizing a number of light antitank assault weapons, fearlessly moved

from position to position firing numerous rounds at the heavily fortified enemy emplacements. He

successfully knocked out a rocket position and suppressed much of the enemy fire before falling

mortally wounded. The heroism, courage, and dynamic leadership displayed by Sergeant Gonzalez

reflects great credit upon himself and the Marine Corps and were in keeping with the highest

traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country."

That was not the only honor that Sergeant Gonzalez received. In 1975 an elementary school in his

hometown of Edinburg, was named in his honor, and in 1993 Navy Secretary John Dalton

announced that the Navy's most advanced and one of its deadliest warships would be named after

him. USS Alfredo Gonzalez (DDG-66), a guided-missle destroyer, was christened at Bath, Main, in

February 1995 and commissioned at Corpus Christi, Texas, in October 1996. The first modern

warship named for a Mexican-American, she is now serving with the Navy's Atlantic Fleet.

Tet Offensive - a turning point

by J ohn Omicinski

Gannett News Service

WASHINGTON - Thirty years ago this week, events in Southeast Asia changed the U.S. presidency, the press, the public and the

Pentagon in ways still reverberating.

On Jan. 30-31, 1968, North Vietnamese troops and their Viet Cong guerrilla allies in South Vietnam mounted a coordinated series of

shock attacks on more than 30 supposedly safe cities - including the South's capital, Saigon.

The Tet Offensive became a watershed news story, changing not only military realities but American politics, journalism and culture.

It also came at the beginning of 1968 which, as it turned out, would be overloaded with tragic events.

6

Dr. Martin Luther King and Sen. Robert Kennedy were assassinated. Riots hit many American cities. After demonstrators overwhelmed

their Chicago nominating convention, Democrats under Vice President Hubert Humphrey were badly split and narrowly lost the

presidency to Richard Nixon.

"There's no doubt Tet was one of the biggest events in contemporary American history," said Don Oberdorfer, a former Washington

Post reporter whose 1971 book "Tet!" remains a central study of those era-changing weeks. "Within two months, the American body

politic turned around on the war. And they were significantly influenced by events they saw on television."

North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh's attackers timed the wave of assaults to catch U.S. and South Vietnamese troops off guard

during the big Asian holiday, called Tet. Nonetheless, they suffered more than 58,000 deaths and suffered serious military setbacks in

succeeding weeks.

U.S. troops lost 3,895 in the next 12 weeks, but the American press portrayed Tet as a severe loss for American and South

Vietnamese troops. That happened partly because Gen. William Westmoreland and U.S. officials said, before Tet, that U.S. efforts had

"turned a corner" in Vietnam.

Tet produced a famous quote from a still-unnamed (and perhaps non-existent) U.S. officer: "We had to destroy the village in order to

save it." And it produced the My Lai massacre, when some U.S. troops went haywire and executed unarmed Vietnamese villagers.

Perhaps most famously, it produced Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams's Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of South Vietnam's

national police chief, Brig. Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan, executing a Viet Cong officer on the streets of Saigon with a pistol shot to his

head.

In graphic television footage and newspaper photos, Americans saw images of Viet Cong guerrillas breaching the U.S. Embassy

compound in Saigon and two Marines dragging a wounded and bloodied buddy from fighting in Hue.

News film from the battlefields was by 1968 transmitted from Tokyo via satellite. Often, the unedited film went straight onto the

airwaves for the evening news in jumbled, unexplained minutes that gave the war an even more chaotic look. Within days of the Tet

attacks, American campuses were in an uproar. Within weeks, many average Americans suddenly turned against the war.

And within two months, after dove Eugene McCarthy made a strong showing in the March 12 New Hampshire Democratic presidential

primary, President Johnson shocked the nation by taking himself out of the 1968 race.

Johnson's withdrawal came as a complete surprise and shock to a nation still reeling from the unexpected events in Vietnam.

Regarded as a watershed, too, was press icon Walter Cronkite's Feb. 27, 1968, broadcast saying the war was "mired in stalemate"

and the "only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as honorable people . . . "

Cronkite's shift into the opposition camp - followed in short order by the editors and opinion-makers at Time and Life magazines -

made it acceptable and almost fashionable for journalists to oppose the war.

"For the first time in modern history," wrote Robert Elegant of the Los Angeles Times, "the outcome of a war was determined not on

the battlefield but on the printed page and, above all, on the television screen.

Tet 30th Anniversary

Tet's 30th anniversary presents a good opportunity to cut through the bodyguard of lies that distort that battle's real significance.

Tet's 30th anniversary presents a good opportunity to cut through the bodyguard of lies that distort that battle's real significance.

If the Vietnam War had a defining moment, it had to be the Tet Offensive of 1968. For today's high school and college students all of

that war is ancient history, and even for those who lived through it, most of its battles have faded. But not Tet. Like Pearl Harbor or

the Cuban missile crisis, it sticks in our collective memory. Unfortunately, however, much of what we "know" about Tet is actually part

of the bodyguard of lies that has distorted its true meaning, leaving many veterans feeling guilty by association for the loss of the

war.

The most enduring untruth about Tet is that it was the turning point of the war. In fact, as University of Rochester Professor John E.

Mueller documented in War, Presidents and Public Opinion (Wiley), the American public actually turned against the war in October

1967, three months before Tet. When U.S. troops first went ashore in Vietnam in 1965, 61 percent of the American people approved

and only 24 percent were opposed. A plurality continued to support the war, albeit in decreasing numbers, for the next 31 months,

until October 1967, when for the first time more Americans opposed the distant war (46 percent) than approved of it (44 percent).

The decline was not due to the efforts of the anti-war movement, which, polls showed, was the most despised group in American

society. American pragmatism was the cause of the decline. "Either win the damn thing or get the hell out," was the public mood.

After all the reassurance from the politicians and generals that all was well, Tet was the icing on the cake, proof positive that we did

not know what we were doing. The perspicacity of the American people was confirmed by Clark Clifford when he took over as

secretary of defense after Tet and found that three years into the ground war the Joint Chiefs of Staff still had no plan for victory.

7

That shortcoming is usually ascribed to ineptitude, but in this issue, Stephen B. Young claims that President Lyndon B. Johnson,

following the lead of his predecessors, never subscribed to the goal of traditional victory and, in fact, had instructed his ambassador

to Vietnam, Ellsworth Bunker, to work toward an eventual U.S. disengagement without losing the war (see story, P. 20). That, says

Young, was achieved in the wake of the 1973 Paris Accords, but was then sabotaged by Congress and by the fecklessness of the Ford

administration.

Competing myths about Tet claim that it was a defeat for the United States, countered by equally strident claims that it was a military

victory. Those opposing views can be reconciled through the use of a military template, for military analysis looks at battlefield events

on three distinct but interlocking levels.

First is the tactical or battlefield level. Second is the operational or theater-of-war level. Third is the strategic or political-military level.

Victory at one level does not necessarily guarantee victory at a higher level. You may indeed win the battle but lose the war. This was

brought home to me in Hanoi a week before the fall of Saigon. "You know you never beat us on the battlefield!" I said to my NVA

counterpart. He thought about that a moment, then replied, "That may be so. But it's also irrelevant."

At the tactical and operational levels, Tet was an enormous victory for the United States and for the South Vietnamese government,

especially when it came to winning the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people, the stated goal of our counterinsurgency

warfare efforts. In his classic work Tet! (Da Capo), Washington Post war correspondent Don Oberdorfer made that clear. "There had

been no General Uprising and nothing resembling the beginning of one," he wrote. "Among the Vietnamese people, the battles had

created doubts about Communist military power. The Liberation Army had attacked in the middle of the Tet truce when the South

Vietnamese Army was on leave, and even so it had been able to achieve only temporary inroads. If the Communists were unable to

take the cities with a surprise attack in such circumstances, they would probably be unable to do better at any other time." It was the

end of the Viet Cong guerrillas. By 1970, 70 percent of enemy forces in the field were NVA regulars.

But at the strategic level it was another matter entirely, as Peter Braestrup, another Washington Post war correspondent whose Big

Story is reviewed in this issue, pointed out. Lyndon Johnson was "psychologically defeated" by Tet. Veterans need to stop blaming

themselves, for if the commander-in-chief is defeated, the nation is defeated, no matter how well military forces in the field may have

performed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This document is taken from two sources "The Orders and Medals of The Communist Governments of Indochina"

John Sylvester Jr.

And the official document published by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam's Institute of Orders (Vien Huan Chuong).

A History of the Democratic/socialist Republic of Vietnam, and Marxist Unification.

The communist in vietnam resembled many others among the Vietnamese nationlist in that they took their creed from abroad - in this

case from Leninism. Ho chi Minh over the years built a disciplined and purposeful organization that broke its nationalist opponents,

outlasted the French and Americans, and finally unified Indochina under its control.

Ho Chi Minh returned from the USSR in 1925 with Borodin's mission to China in order to form a communist movement in Indochina,

called first the Revolutionary Youth League and later in 1930 the Indochinese Communist Party. The party in 1930 led a peasant

uprising in the central provinces of Nghe An and Ha Tinh and created village "soviets" which were soon crushed by the French

military. The party returned to clandestinity. It built a first guerilla base in upland Cao Bang and Bac Son, participating in an abortive-

uprising in the fall of 1940. In May 1941 the party formed a broad united front called the League for the Indepedence of Vietnam

(Vietnam Doc-Lap Dong-Minh Hoi, or in short, the Viet Minh). (The term Viet Cong, the contraction for Vietnamese communist, was

later used by opponents more with the implication of the southern arm of the movement).

The party carefully refrained from challenging the Japanese, and prepared for the day of Japan's defeat. After the French were

interned in March 1945 and the Japanese conceded defeat on August 16, the party moved to seize the opportunity. Armed

Propaganda Teams demonstrated across the country. On September 2, 1945, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was proclaimed

and the flag of a five pointed yellow star on a red field was hoisted. Ho Chi Minh became the president of the Provisional People's

Government.

The Viet Minh moved to mollify the Chinese occupiers, keep out the French and destroy such native rivals as the VNQDD and

Trotskyites. The Viet Minh did well in consolidating its position except in the south, where they faced the opposition of the sects and

the British and French forces. In March 6, 1946, agreement, the French government, "recognized the Republic of Vietnam as a free

state which has its own governmment, parliament, army, and finances and which is part of the Indochinese Federation and the French

Union." (But a seperate French controlled Republic of Cochinchina was proclaimed June 1, 1948, with a flag of three horizontal blue

stripes on yellow.) Although the French even for a short while helped the Viet Minh combat its nationlist rivals, French policy

hardened, particularly as carried out on the scene by Admiral d' Argenlieu. In concert, the Viet Minh took a harsher line, for instance,

holding public ceremonies where citizens burned their French diplomas and destroyed their French medals.

8

The communist army claims its official orgin in the first "Platoon of National Salvation" formed in the 1940 uprising. In December

1944 Ho Chi Minh created the "Vietnamese People's Propaganda Unit for National Liberation," which became in September 1945, with

the new republic, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN). Under the capable General Vo Nguyen Giap the PAVN was built quickly using

the concept of a people's war, arms of varied orgin, and a balance of political indoctrination and military professionalism. by 1946 it

had about 100,000 men under arms, plus 35,000 paramilitary, and it continued to expand steadily thereafter. It fought with both

great courage and heavy casualties, taking at times beatings from the French forces, but also securing major victories at Cao Bang in

1950, over Group Mobile 100 in 1953, and finally at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The divisions then consisted of the 304th, 308, 312th,

316th, and 320th, and the 351st Heavy Division.

The Indochinese Communist Party, following recongnition by Peking and Moscow of the DRV in 1950, abandoned its clandestinity and

changed its name to the Vietnam Workers Party (Dan Lao-Dong Vietnam). with the partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel as a

result of the Geneva agreements, the DRV gained full territoral control of the north. As its soldiers and cadre were "regrouped" to the

north, the DRV apparently abandoned its position in the south pending unification of the country under an election to be held

according to the terms of the agreement. The election was never held, Diem believing the communists would not tolerate any true

one. As the Diem government unexpectedly reduced the chaos of the south and gained control, the communist had to rethink their

strategy for the south. They initially, however, were preoccupied with building their own system in the north, partly through the brutal

purges of the "land reform" program.

Starting in 1959 several thousand of the "regroupees" southern cadre were again sent to the south and there began again the effort

to achieve "a general uprising". There was then announced a purportedly seperate party for the south, the People's Revolutionary

Party (Dang Nhan-Dan Cach-Mang), and a broader front organization the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam-NLF

(Mat-Tran Dan-Toc Giai-Phong Mien-Nam). Control was retained in Hanoi and discipline over the southerners ensured by the security

apparatus. The flag of the NLF was half red, half light blue with a gold star in the center, close to that of the DRV. In December 1963

the Ninth Conference of the Central Executive Committee made the decision for a full effort to take the south, and the Second

Indochina War commenced in earnest.

In 1957 the PAVN had been systematically modernized on the Soviet model. Previously officers were designated by function, such as

battalion commander, and had no rank and wore no insignia. Following a 1958 law, ranks were established and insignia and epaulets

worn. The PAVN soldiers and units sent to the south, in order to maintain the pretense of a separate southern movement, used the

functional rank designations of the People's Liberation Armed Force of South Vietnam (PLAF) and their more modest insignia and

decorations. Military operations in central Vietnam, however, were controlled directly from the north, and that area was divided into

four tactical zones: the CMA Front, Military Region Tri Thien Hue, Military Region 5 below on the coast, and the B-3 Front inland.

Military operations further south were controlled by the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), located usually on the Cambodian

border directly north of Saigon.

After the "Special war" of 1961-63 against the strategic hamlet program and the shaky ARVN, the communist forces then challenged

in "armed struggle" the entering American units. Local guerilla and regional forces were intended to provide a "seething quality in the

coordinated struggle", while the main forces carried out "annihilating blows" that would cause "turning points in the war." Put on the

defensive by the hard pressing American units, the communists husbanded their forces for a major offensive during Tet 1968. They

achieved the desired surprize in attack, and impetus to the antiwar movement in the US, but the southern communist units were so

heavily blooded that thereafter the southern communists had little role in the war. The PLAF divisions, the 3rd, 5th and 9th, were

largely thereafter staffed by PAVN soldiers infiltrated down the impressive road supply network from the north. The DRV did not

acknowledge its direct involvement in the war in the south, and unit desifnations were camouflaged.

A COSVN directive of early 1971 called for continuing attacks to achieve "piecemeal" victories and to defeat pacification and

Viernamization. While achieving on the ground no real victories against the US forces, the communists kept the blood flowing and the

bulk of their forces safe in Cambodia. They caused the Americans, just like the French, to grow tired of the political burden and to

abandon the war. In January 1973 there were some 220,000 PAVN troops in the south comprising 15 infantry divisions and many

independent infantry, sapper, artillery, armor, anti-aircraft regiments, the rear service and other units. Five divisions (304, 312,

320B, 324B and 325) were north of the Hai Van Pass in MR- I and two were south (711 and 2nd). In MR-2 there were three divisions

(3rd, 1oth, and 320); in MR-3 two (7th and 9th); and in MR-4 three (1st, 5th and 6th). Other divisions were in the north and Laos.

In the 1973 Paris accord the US gained its prisoners back, but did not get the communist to withdraw their forces from the south. The

DRV got the US out of Vietnam, but did not get the US to pull down Thieu and the Republic of Vietnam as it left. But the Provisional

Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG) did gain status from its participation in the talks. With President

Nixon's political collapse, US pledges of continued support for the Republic of Vietnam proved false. The spurious peace disappeared.

By 1975 the PAVN was better armed by the Soviets and Chinese than the ARVN was by the US. It also had far more maneuverable

battalions. In the major offensive of 1975 the ARVN fell apart and "unification" was achieved. It was a victory of the main force PAVN

units, manifested in the Saigon victory parade in May which featured bemedaled. brass bands, tanks, SAM missiles, and only a few

southern guerillas.

Victory was also celebrated by the elevation of the name of the state to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the party to the

Vietnam Communist Party (Dang Cong-San Vietnam). The PRG disappeared with the formal unification of the country.

The aftermath was disappointing to the communist. Hanoi could manage war, but not peace, and certainly not an economy. The

attractions of the rich south, moreover, corrupted veteran cadra; the southerners were resentful of northern control; and a major

border war developed with the vicious Khmer Rouge. This was complicated by a deepening quarrel with China, which was angered

over Vietnam's proud and ungrateful attitude and deepening ties with the USSR. The PAVN was expanded to some 33 infantry, 12

economic construction, and 6 engineer divisions. In January 1978 it blitzkrieged Democratic Kampuchea but had to leave there for the

protection of its client state the 5th, 302nd, 307th, 309th, and part of the 950th divisions. The border war of February-March 1978

9

with China was a standoff, although the Vietnamese second line border units fought well. The SRV was the most formidable military

power of Southeast Asia, but also isolated, improverished, and heavily dependent on Soviet aid.

Later, tiring of the quagmire in Cambodia and of the economic and diplomatic costs of its intervention there, Hanoi reluctantly and

gradually pulled its forces out, leaving the problem to the United Nations. with the distressing collapse of communism in East Europe

and the Soviet Union, Hanoi cautiously mended its relations with Beijing. They remained divided over the rancor of history and

competing territorial claims on the border and the South china Sea. But they shared interest as two of the only four remaining

communist states. Moreover, the SRV, just as the PRC, was proceeding with economic libeeralization, while resisting political

liberalization. As fears by its ASEAN neighbord, the international community, and even the US.

The Medals: The Vietnamese communist movement began as a revolutionary political and partisan movement with the formal

simplicity that implies. But it was also influenced by the French and Soviet experience, and that led to the adoption of a system of

decoration and medals. Chairman Ho Chi Minh on January 26th, 1946, promulgated a decree listing ten categories of people who

deserved awards, including those who had sacrificed for the country, saved lives, and those who contributed three children to the

forces. According to information from prisoners and from examples found on the batttlefiels, medals were first awarded to communist

combatants and sympathizers at the end of 1947. The decorations were often presented as collective or unit awards. A unit receiving

the Southern medal would be presented the accompanying appellation "Valiant Unit in the Annihilation of Americans." A company

sized unit, for instance, would be eligible for this for destroying supposedly two US platoons in a single battle. Examples of other unit

awards mentioned by Hanoi radio include the Ho Chi Minh Order 3rd class given to the Engineer Corps command on the 25th

anniversary of its founding, March 25, 1980; and the Labor Medal First Class given to the Cadre of Nghia Binh province, March 30,

1978 for combatting illiteracy. Units as well as individuals, could be promoted after successes to a higher class award. Unit

awardsmight be indicated by the presentation of a red banner with an appropriate inscription such as "Resolved to Win" (Quyet

Thang.) Subsequent awards were often shown by pinning medals to the unit flag; the flags of some combat units are photographed

heavily incrusted with medals.

The award documents were often colorful with flags, ornamented borders, or pictures of the medal. Many were of postcard size and

lithographed. Entries on the documents were often in handwriting and sometimes typewritten. Following standard Vietnamese

practise, the seals were round and red. The documents reverse might carry space for entries of additional awards of the medal in its

various classes.

US Marines in Vietnam

This section covers the history of the U.S. Marines in Vietnam. It includes their

operations and personal accounts of battles fought, lives lost and victories won. It is

difficult to put on paper the feelings of the men who were Marines; they are a

different breed, they were Marines.

"It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man

stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to

the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by the dust and sweat

and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs and comes short again and again; who

knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions and spends himself in a worthy

course; who at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who,

at worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly; so that his place shall never be

with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory or defeat."

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

(Paris Sorbonne, 1910)

History has a strange way of repeating itself. In May 1845, American Marines went ashore from the USS Constitution in an attempt to

release a French Catholic missionary from prison. "Old Ironsides" was anchored at Touron Bay, Cochin, China, during her cruise

around the world. Touron Bay is known today as "Da Nang."

Much has happened since that first landing in Vietnam by American Navy men and Marines, over 125 years ago. Following the signing

of the Geneva accords, Bedell Smith, representing the American delegation, stated that the United States would not threaten or use

force to disturb the accords, and "would view any renewal of aggression in violation of the Agreements with grave concern as

seriously threatening international peace and security."

Enemy troops continued infiltrating from the north. The monsoon rains came, bogging down the mechanized army of the south, but

guerrillas don't need wheels.

As the rains fell heavily, the guerrilla units began strong offensives in every major sector of operations, including the southern deltas,

central highlands and the mountainous north.

It was then that the USS Maddox was attacked in international waters by North Vietnamese PT boats, an attack referred to as the Gulf

of Tonkin incident.

10

During a sneak night attack, the VC hit the air base at Pleiku in the central highlands. The American barracks was rocketed; aircraft

and helicopters were shredded. Eight Americans were killed; 125 more wounded.

The enemy then struck at Qui Nhon in Central Vietnam. The Americans counted their casualties.

The decision was made. Land the Marines!" March 8, 1965, began cloudy and windy. There was a pounding surf and a strong

offshore wind. Breakers reached 20 feet. The landing was delayed.

Then the small landing craft reached the beach. Ramps ground open and the Marines stormed ashore. They were greeted by a mob of

photographers, local officials and Vietnamese schoolgirls. Secretary of State Dean Rusk was asked if Marines would shoot back if fired

on "Obviously," he replied. "That's the history of the Corps."

The 3d Bn., Ninth Marines waded ashore 10 miles west of Da Nang. They were part of the Ninth Marine Expeditionary Brigade,

commanded by Brigadier General Frederick J. Karch. Once ashore, the Ninth Marines linked up with the Ist Bn., Third Marines which

landed by C-130 Hercules transport aircraft later in the day.

A month prior to the arrival of the Marine ground troops, a battery of Marine HAWK missiles was transferred to Vietnam for the

defense of the Da Nang Air Base. In support of the grunts, or infantry Marines, came Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron-162 from

Okinawa, which would bolster its sister squadron, HMM-163. Marine Observation Squadron-2 landed the following day. The Marines

surrounded the air base, weapons at the ready. Some moved atop Hill 327 that dominated numerous approaches to the air base. To

many, it was "just another landing." Not a single shot was fired; not a casualty was suffered. The lack of pain and bloodshed would

not be absent for long; sea breezes along the South China Sea would soon carry the smell of gunpowder, echoes of shells firing and

blood would spill on both sides. But for now, at least, it was just another landing. It was "move out...spread out, hurry up and wait."

It was hot. Throats were dry, backs wet with sweat and feet soaked from flooded rice paddies. Units moved to establish a perimeter

defense around the Da Nang Air Base and helicopter landing zones. They were on Hill 327 and Monkey Mountain. The Marines had

landed!

Click on any link to the left to read the articles on

The United states Army in Vietnam

Click on any link to your left for a review of the Army's role in Vietnam

America's Longest War

The Vietnam War was the longest military conflict in U.S. history. The hostilities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia claimed the lives of

more than 58,000 Americans. Another 304,000 were wounded. The Vietnam War was a military struggle fought in Vietnam from 1959

to 1975, involving the North Vietnamese and the National Liberation Front (NLF) in conflict with United States forces and the South

Vietnamese army. From 1946 until 1954, the Vietnamese had struggled for their independence from France during the First Indochina

War. At the end of this war, the country was temporarily divided into North and South Vietnam. North Vietnam came under the

control of the Vietnamese Communists who had opposed France and who aimed for a unified Vietnam under Communist rule. The

South was controlled by Vietnamese who had collaborated with the French. In 1965 the United States sent in troops to prevent the

South Vietnamese government from collapsing. Ultimately, however, the United States failed to achieve its goal, and in 1975 Vietnam

was reunified under Communist control; in 1976 it officially became the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. During the conflict,

approximately 3 to 4 million Vietnamese on both sides were killed, in addition to another 1.5 to 2 million Lao and Cambodians who

were drawn into the war.

The Vietnam War was the longest and most unpopular war in which Americans ever fought. And there is no reckoning the cost. The

toll in suffering, sorrow, in rancorous national turmoil can never be tabulated. No one wants ever to see America so divided again.

And for many of the more than two million American veterans of the war, the wounds of Vietnam will never heal. Fifty-eight thousand

Americans lost their lives. The losses to the Vietnamese people were appalling. The financial cost to the United States comes to

something over $150 billion dollars. Direct American involvement began in 1955 with the arrival of the first advisors. The first combat

troops arrived in 1965 and we fought the war until the cease-fire of January 1973. To a whole new generation of young Americans

today, it seems a story from the olden times.

No event in American history is more misunderstood than the Vietnam War. It was misreported then, and it is misremembered now.

Richard M. Nixon, 1985

También podría gustarte

- An Introduction To The My Lai CourtsDocumento9 páginasAn Introduction To The My Lai Courtsrng414Aún no hay calificaciones

- America's Backpack Nuke: A True Account: Love, War, History and Drama - The Mission Was Far Beyond the Call!De EverandAmerica's Backpack Nuke: A True Account: Love, War, History and Drama - The Mission Was Far Beyond the Call!Aún no hay calificaciones

- Along for the Ride: Navigating Through the Cold War, Vietnam, Laos & MoreDe EverandAlong for the Ride: Navigating Through the Cold War, Vietnam, Laos & MoreAún no hay calificaciones

- Mr. Gott TributeDocumento7 páginasMr. Gott TributeCameron NyeAún no hay calificaciones

- Personal Recollections of the War of 1861 As Private, Sergeant and Lieutenant in the Sixty-First Regiment, New York Volunteer InfantryDe EverandPersonal Recollections of the War of 1861 As Private, Sergeant and Lieutenant in the Sixty-First Regiment, New York Volunteer InfantryAún no hay calificaciones

- Sergeant William Johnson Is Hanged For Desertion and An Attempt To Outrage The Person of A Young Lady at The NewDocumento6 páginasSergeant William Johnson Is Hanged For Desertion and An Attempt To Outrage The Person of A Young Lady at The NewJohn PeacockAún no hay calificaciones

- Analysis of Lunev Chapter 2Documento3 páginasAnalysis of Lunev Chapter 2Jeffrey RussellAún no hay calificaciones

- Commanders of World War TwoDocumento220 páginasCommanders of World War TwoJefferson de Deus LeiteAún no hay calificaciones

- Experience of a Confederate States Prisoner (Memoirs)De EverandExperience of a Confederate States Prisoner (Memoirs)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Armed with Abundance: Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam WarDe EverandArmed with Abundance: Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam WarCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (3)

- Personal Recollections of the War of 1861: As Private, Sergeant and Lieutenant in the Sixty-First Regiment, New York Volunteer InfantryDe EverandPersonal Recollections of the War of 1861: As Private, Sergeant and Lieutenant in the Sixty-First Regiment, New York Volunteer InfantryAún no hay calificaciones

- A Moment in TimeDocumento714 páginasA Moment in Timebiggjohn85usAún no hay calificaciones

- Grandpaprofile 1Documento4 páginasGrandpaprofile 1api-272095034Aún no hay calificaciones

- Flags of FathersDocumento3 páginasFlags of Fathersapi-254277473Aún no hay calificaciones

- The American Experience in Vietnam: Reflections on an EraDe EverandThe American Experience in Vietnam: Reflections on an EraCalificación: 1 de 5 estrellas1/5 (1)

- Battlelines: Road to Gettysburg: Civil War Combat Artists and the Pictures They Drew, #1De EverandBattlelines: Road to Gettysburg: Civil War Combat Artists and the Pictures They Drew, #1Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Victors: Eisenhower And His Boys The Men Of World War IiDe EverandThe Victors: Eisenhower And His Boys The Men Of World War IiCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (108)

- The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America’s MilitaryDe EverandThe Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America’s MilitaryAún no hay calificaciones

- The Life and Times of Sgt. Joseph Thomas "Tom" Biway, USMCDe EverandThe Life and Times of Sgt. Joseph Thomas "Tom" Biway, USMCAún no hay calificaciones

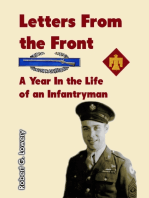

- Letters From the Front: A Year in the Life of an InfantrymanDe EverandLetters From the Front: A Year in the Life of an InfantrymanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Battle of Wilson's Creek: Union troops, commanded by Gen. N. Lyon VS. the Confederate troops, under command of Gens. McCulloch and Price, August 10, 1861De EverandThe Battle of Wilson's Creek: Union troops, commanded by Gen. N. Lyon VS. the Confederate troops, under command of Gens. McCulloch and Price, August 10, 1861Aún no hay calificaciones

- Three Paths To GettysburgDocumento132 páginasThree Paths To GettysburgGordon Fisher100% (3)

- Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant: Their Epic BattleDe EverandAndrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant: Their Epic BattleAún no hay calificaciones

- Wwii Interview - Samuel McfaddenDocumento17 páginasWwii Interview - Samuel Mcfaddenapi-423085333Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ride the Razor's Edge: The Younger Brothers StoryDe EverandRide the Razor's Edge: The Younger Brothers StoryCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Memoir of Tillie Pierce: An Eyewitness to the Battle of GettysburgDe EverandMemoir of Tillie Pierce: An Eyewitness to the Battle of GettysburgAún no hay calificaciones

- 03-17-08 DN!-1968, Forty Years Later Seymour Hersh InterviewDocumento6 páginas03-17-08 DN!-1968, Forty Years Later Seymour Hersh InterviewMark WelkieAún no hay calificaciones

- Richard Boyle: GI Revolts - The Breakdown of The US Army in VietnamDocumento35 páginasRichard Boyle: GI Revolts - The Breakdown of The US Army in VietnamBloom100% (1)

- James Jesus AngletonDocumento44 páginasJames Jesus AngletonSinead MarieAún no hay calificaciones

- My Lai JstorDocumento10 páginasMy Lai Jstorapi-247847830Aún no hay calificaciones

- Our Jungle Road To Tokyo [Illustrated Edition]De EverandOur Jungle Road To Tokyo [Illustrated Edition]Aún no hay calificaciones

- B7 Conflict in Vietnam History Gcse PaperDocumento2 páginasB7 Conflict in Vietnam History Gcse PaperseongilAún no hay calificaciones

- The Balangiga MassacreDocumento7 páginasThe Balangiga MassacreRochelle LluzAún no hay calificaciones

- To the End of the War: Unpublished FictionDe EverandTo the End of the War: Unpublished FictionCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (17)

- War Dawgs: Kulbes' Mongrels in Korea, 1950-1951De EverandWar Dawgs: Kulbes' Mongrels in Korea, 1950-1951Aún no hay calificaciones

- (1927) Complete History of The Southern Illinois' Gang WarDocumento102 páginas(1927) Complete History of The Southern Illinois' Gang WarHerbert Hillary Booker 2ndAún no hay calificaciones

- Guns On Cemetery HillDocumento30 páginasGuns On Cemetery HillcrdewittAún no hay calificaciones

- My Lai MassacreDocumento11 páginasMy Lai MassacreNick Adilah100% (1)

- The Brave LegendDocumento78 páginasThe Brave LegendGary R Boyd, PemapomayAún no hay calificaciones

- The Battle of Wilson's Creek: Union troops, commanded by Gen. Lyon VS. Confederate troops, commanded by Gens. McCulloch and PriceDe EverandThe Battle of Wilson's Creek: Union troops, commanded by Gen. Lyon VS. Confederate troops, commanded by Gens. McCulloch and PriceAún no hay calificaciones

- Wrapped in Danger: World War II Gifts Surface With Perilous ConsequencesDe EverandWrapped in Danger: World War II Gifts Surface With Perilous ConsequencesAún no hay calificaciones

- Sharon OldsDocumento2 páginasSharon OldsGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Gaiman TraducciónDocumento4 páginasGaiman TraducciónGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Jameson at Escuela Sur English TranscriptionDocumento21 páginasJameson at Escuela Sur English TranscriptionGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- An Interview CarverDocumento20 páginasAn Interview CarverGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Birds in The MouthDocumento11 páginasBirds in The MouthGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- An Interview CarverDocumento20 páginasAn Interview CarverGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- An Interview CarverDocumento20 páginasAn Interview CarverGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- English 121 Aimee Bender The Rememberer PDFDocumento7 páginasEnglish 121 Aimee Bender The Rememberer PDFGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- ULYSSES AnnotatedDocumento3 páginasULYSSES AnnotatedGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Does Abortion Increase Women's Risk For PTSD BMJ 2015Documento13 páginasDoes Abortion Increase Women's Risk For PTSD BMJ 2015Graciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- The Eyes Have ItDocumento2 páginasThe Eyes Have ItNastazia JolieAún no hay calificaciones

- Bender, Aimee - The RemembererDocumento3 páginasBender, Aimee - The RemembererJen JulianAún no hay calificaciones

- Conrad ImperialismDocumento8 páginasConrad ImperialismGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Conrad ImperialismDocumento8 páginasConrad ImperialismGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Recognising Lecture StructureDocumento10 páginasRecognising Lecture StructureGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Letter EndingsDocumento3 páginasLetter EndingsGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- KinshipDocumento2 páginasKinshipGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- TG Preview The Thing Around Your NeckDocumento10 páginasTG Preview The Thing Around Your NeckGraciela Rap50% (2)

- A Perfect Day For BananafishDocumento25 páginasA Perfect Day For BananafishGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethan Frome SummariesDocumento3 páginasEthan Frome SummariesGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- New Media and The Power of Networks: First Dixons Public Lecture and Inaugural Professorial LectureDocumento23 páginasNew Media and The Power of Networks: First Dixons Public Lecture and Inaugural Professorial LectureGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Adjectives and Relative ClausesDocumento3 páginasAdjectives and Relative ClausesGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Recognising Lecture StructureDocumento10 páginasRecognising Lecture StructureGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Essays On BananafishDocumento10 páginasCritical Essays On BananafishGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- A Brief History of The USDocumento8 páginasA Brief History of The USGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse Analysis - Term TestDocumento4 páginasDiscourse Analysis - Term TestGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Tabloidization of EmilyDocumento27 páginasTabloidization of EmilyGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Chimamanda Ngozi AdichieDocumento8 páginasChimamanda Ngozi AdichieGraciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- Slaughterhouse 5Documento2 páginasSlaughterhouse 5Graciela RapAún no hay calificaciones

- USAF1Documento96 páginasUSAF1barry_jive100% (2)

- El Trópico Según Pierre GourouDocumento20 páginasEl Trópico Según Pierre GouroucesarquispecosarAún no hay calificaciones

- Ho Chi Minh by Milton OsborneDocumento8 páginasHo Chi Minh by Milton OsborneJanina LouiseAún no hay calificaciones

- Milrev Apr1972Documento116 páginasMilrev Apr1972mikle97Aún no hay calificaciones

- Bai Tap On Mon Tieng Anh 6 9 Tu Ngay 02 03 2020 Co Dinh Cam Tu Part02Documento52 páginasBai Tap On Mon Tieng Anh 6 9 Tu Ngay 02 03 2020 Co Dinh Cam Tu Part02Chii VũAún no hay calificaciones

- The Illustrated History of The Vietnam War Personal Firepower PDFDocumento164 páginasThe Illustrated History of The Vietnam War Personal Firepower PDFNikos Chalkidis100% (7)

- Dien Bien PhuDocumento31 páginasDien Bien PhuAlexander Green100% (4)

- Decolonisation of IndochinaDocumento18 páginasDecolonisation of Indochinaitsduhtom100% (2)

- The Fourth Indo-China War - Nguyen Kim Hoa - Bryan S. TurnerDocumento8 páginasThe Fourth Indo-China War - Nguyen Kim Hoa - Bryan S. Turnernvh92Aún no hay calificaciones

- Dien Bien Phu MainDocumento18 páginasDien Bien Phu MainManish Yadav100% (1)

- The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1961-1973Documento391 páginasThe United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1961-1973Bob Andrepont100% (1)

- The Art of War 6 To 9Documento2 páginasThe Art of War 6 To 9Dana TalamAún no hay calificaciones

- Thayer Vietnam People's Army: Corporate Interests and Military ProfessionalismDocumento26 páginasThayer Vietnam People's Army: Corporate Interests and Military ProfessionalismCarlyle Alan ThayerAún no hay calificaciones

- Peter MacDonald - Soldiers of Fortune - The Twentieth Century Mercenary-Gallery Books (1986) PDFDocumento200 páginasPeter MacDonald - Soldiers of Fortune - The Twentieth Century Mercenary-Gallery Books (1986) PDFisbro178880% (5)

- History & Geography 7.5.2023Documento5 páginasHistory & Geography 7.5.2023Tri LeAún no hay calificaciones

- LectureWas The Vietnam War WinnableDocumento7 páginasLectureWas The Vietnam War WinnableMartin Scott CatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ang BayanDocumento11 páginasAng BayannpmanuelAún no hay calificaciones

- Containment in VietnamDocumento51 páginasContainment in VietnamNishanth ButtaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Battle of Dien Bien PhuDocumento22 páginasThe Battle of Dien Bien PhuPenjejakBadaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Aces and Aerial Victories The USAF in The SEA, 1965-1973Documento202 páginasAces and Aerial Victories The USAF in The SEA, 1965-1973Bob Andrepont100% (4)

- De Thi Hoc Ki 2Documento17 páginasDe Thi Hoc Ki 2Hang TranAún no hay calificaciones

- Target Saigon 1973-1975 Volume 3 Disaster at Da Nang March 1975 (Albert Grandolini) (Z-Library)Documento82 páginasTarget Saigon 1973-1975 Volume 3 Disaster at Da Nang March 1975 (Albert Grandolini) (Z-Library)Freedel Logie100% (2)

- Review Vietnam Epic TragedyDocumento4 páginasReview Vietnam Epic TragedyCao DuyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Vital Role of Intelligence in Counterinsurgency Operations PDFDocumento36 páginasThe Vital Role of Intelligence in Counterinsurgency Operations PDFstavrospalatAún no hay calificaciones

- Viet Nam 1945 - 1954Documento6 páginasViet Nam 1945 - 1954Russell StevensonAún no hay calificaciones

- Battle of Dien Bien PhuDocumento11 páginasBattle of Dien Bien PhuAdi SusetyoAún no hay calificaciones

- 68 76Documento50 páginas68 76tAún no hay calificaciones

- The Manifold Partisan: Anti-Fascism, Anti-Imperialism, and Leftist Internationalism in Italy, 1964-76Documento28 páginasThe Manifold Partisan: Anti-Fascism, Anti-Imperialism, and Leftist Internationalism in Italy, 1964-76prateekvAún no hay calificaciones

- Changing Worlds - Vietnam's Transition From Cold War To Globalization (2012) David W.P. ElliottDocumento433 páginasChanging Worlds - Vietnam's Transition From Cold War To Globalization (2012) David W.P. Elliottnhoa_890316Aún no hay calificaciones

- People's War Comes To The Towns: Tet 1968: Liz HodgkinDocumento7 páginasPeople's War Comes To The Towns: Tet 1968: Liz Hodgkinlucitez4052Aún no hay calificaciones

![Our Jungle Road To Tokyo [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/293579681/149x198/d02da53404/1617234265?v=1)