Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Journal Medicine: The New England

Cargado por

'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Journal Medicine: The New England

Cargado por

'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

Vol ume 336 Number 22

1541

The New England

Journal

of

Medicine

Copyr i ght, 1997, by t he Massachuset ts Medi cal Soci et y

VOLUME 336

M

AY

29, 1997

NUMBER 22

COMPARISON OF CONVENTIONAL ANTERIOR SURGERY AND LAPAROSCOPIC

SURGERY FOR INGUINAL-HERNIA REPAIR

M

IKE

S.L. L

IEM

, M.D., Y

OLANDA

VAN

DER

G

RAAF

, M.D., C

EES

J.

VAN

S

TEENSEL

, M.D., R

OELOF

U. B

OELHOUWER

, M.D.,

G

EERT

-J

AN

C

LEVERS

, M.D., W

ILLEM

S. M

EIJER

, M.D., L

AURENTS

P.S. S

TASSEN

, M.D., J

OHANNES

P. V

ENTE

, M.D.,

W

IBO

F. W

EIDEMA

, M.D., A

UGUSTINUS

J.P. S

CHRIJVERS

, P

H

.D.,

AND

T

HEO

J.M.V.

VAN

V

ROONHOVEN

, M.D.

A

BSTRACT

Background

Inguinal hernias can be repaired by

laparoscopic techniques, which have had better re-

sults than open surgery in several small studies.

Methods

We performed a randomized, multicenter

trial in which 487 patients with inguinal hernias were

treated by extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair and

507 patients were treated by conventional anterior

repair. We recorded information about postoperative

recovery and complications and examined the pa-

tients for recurrences one and six weeks, six months,

and one and two years after surgery.

Results

Six patients in the open-surgery group but

none in the laparoscopic-surgery group had wound

abscesses (P

0.03), and the patients in the laparo-

scopic-surgery group had a more rapid recovery

(median time to the resumption of normal daily

activity, 6 vs.10 days; time to the return to work, 14

vs. 21 days; and time to the resumption of athletic

activities, 24 vs. 36 days; P

0.001 for all compari-

sons). With a median follow-up of 607 days, 31 pa-

tients (6 percent) in the open-surgery group had re-

currences, as compared with 17 patients (3 percent)

in the laparoscopic-surgery group (P

0.05). All but

three of the recurrences in the latter group were with-

in one year after surgery and were caused by sur-

geon-related errors. In the open-surgery group, 15 pa-

tients had recurrences during the first year, and 16

during the second year. Follow-up was complete for

97 percent of the patients.

Conclusions

Patients with inguinal hernias who

undergo laparoscopic repair recover more rapidly and

have fewer recurrences than those who undergo open

surgical repair. (N Engl J Med 1997;336:1541-7.)

1997, Massachusetts Medical Society.

From the Department of Surgery, University Hospital Utrecht, Utrecht

(M.S.L.L., T.J.M.V.V.); the Department of Epidemiology and Public

Health, University of Utrecht, Utrecht (Y.G., A.J.P.S.); the Department of

Surgery, Ikazia Hospital, Rotterdam (C.J.S., R.U.B., W.F.W.); the Depart-

ment of Surgery, Diakonessenhuis, Utrecht (G.-J.C.); the Department of

Surgery, St. Clara Hospital, Rotterdam (W.S.M.); the Department of Sur-

gery, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft (L.P.S.S.); and the Department of

Surgery, Hofpoort Hospital, Woerden (J.P.V.) all in the Netherlands.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Liem at the Department of General Sur-

gery, University Hospital Utrecht, G04.228, P.O. Box 85.500, 3508 GA

Utrecht, the Netherlands.

NGUINAL hernias are common, and although

the results of surgical repair are often satisfac-

tory, postoperative recovery may be slow, and

the hernia may recur. The period of recovery

after repair of inguinal hernia in patients with paid

recovery time is four to six weeks in most Western

countries.

1-4

Elimination of anxiety about resuming

work could shorten the recovery, but this possibility

has not been studied.

5

Recurrence rates have ranged from less than 1 per-

cent to more than 10 percent, with a follow-up of

more than five years.

4,6

These data should be viewed

with some caution, however, because follow-up data

are often incomplete and unreliable.

4,7

Indeed, the

overall recurrence rate in the Netherlands, the Unit-

ed Kingdom, and the United States and the results

of large, prospective, controlled studies suggest high-

er rates (up to 15 percent after five years).

3,7-9

Laparoscopic techniques for the repair of inguinal

hernias have recently been introduced,

10,11

and in

several small trials, these techniques proved superior

to open repair in terms of postoperative pain and re-

covery.

12,13

These studies were too small, however, to

detect differences in recurrence rates.

8,14-16

We conducted a multicenter, randomized study

to compare conventional anterior repair with extra-

peritoneal laparoscopic repair in terms of postoper-

I

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1542

May 29, 1997

The New Engl and Journal of Medi ci ne

ative recovery, complications, and recurrence rates

in patients with primary or first recurrent unilateral

hernias.

METHODS

We selected teaching and nonteaching hospitals in rural and ur-

ban regions for this study. The sex and age distributions of the

people living in these regions were similar to those in the Nether-

lands as a whole.

17

The surgeons in participating hospitals en-

rolled patients in the study. The study was approved by the ethics

committees at all the hospitals and by the Dutch Health Insur-

ance Council, and all patients gave informed consent.

Characteristics of the Patients

Patients over 20 years old who presented with clinically diag-

nosed, unilateral inguinal hernias (primary hernias or first recur-

rences) who were scheduled to undergo surgical repair with gen-

eral anesthesia were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria were

an additional surgical intervention planned during the hernia re-

pair; a history of extensive lower abdominal surgery, severe local

inflammation, or radiotherapy; advanced pregnancy (

12 weeks

gestation); and previous participation in the study (contralateral

hernia). Patients who were mentally incompetent or not able to

speak Dutch were also excluded.

Base-Line Studies

A standardized history was obtained, and a physical examina-

tion performed. Before randomization, the patients were told

both orally and in writing that they should resume normal activ-

ity after surgery, including work and sports, when they felt able

to do so. It was emphasized that this recommendation applied to

both surgical techniques.

Random Assignment to Treatment Groups

The patients were randomly assigned to either conventional an-

terior repair or extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair, with the as-

signments made at a central office. Randomization was carried out

by telephone, according to a computer-generated list, in groups of

25 or 50 patients; within each of these groups, the maximal allow-

able difference in the number of patients assigned to the two treat-

ments was 4. To ensure an equal distribution of patients in the

two treatment groups, they were stratified according to the hos-

pital and the type of hernia (primary or first recurrent).

Surgical Techniques

All 87 surgeons and residents who performed hernia repairs us-

ing the conventional anterior approach were experienced in this

technique or were supervised by an experienced surgeon. The re-

pair consisted of a reduction of the hernia, ligation of the hernial

sac, if necessary, and reconstruction of the inguinal floor with

nonabsorbable sutures, if necessary. A mesh prosthesis was not

used unless adequate repair was otherwise not possible.

Of the 87 surgeons and residents, 23 also performed laparo-

scopic repairs. They had ample experience with other laparoscopic

procedures and acquired experience with this particular procedure

under the supervision of experienced surgeons before they were

allowed to participate in the trial.

The laparoscopic technique has been described elsewhere.

18

It

was usually performed with the patient under general anesthesia.

Balloon dissection was used to develop the preperitoneal space

without entering the abdominal cavity. Extensive lateral dissec-

tion was performed, with isolation and manipulation of the struc-

tures of the spermatic cord. A polypropylene mesh (10 cm by 15

cm) was placed over the myopectineal orifice. The mesh was not

split and was not fixed in place. Patients were catheterized only if

a full bladder was suspected. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy was

not commonly given in either group.

Data Collection and Follow-up

Standardized data collection was performed by the attending

resident or surgeon, and each patient was evaluated at the hospi-

tal monthly by a physician or data manager from the central study

office. The hernia was classified as type I, II, III (subtype A, B,

or C), or IV (subtype A, B, or C), according to the classification

of Nyhus.

19

The operation time was defined as the time from the

first incision to the placement of the last suture.

We collected information about multiple operative and postop-

erative complications. The operative complications were bleeding

from epigastric or testicular vessels, injury to the vas deferens,

nerve injuries, peritoneal defects or defects in the hernial sac,

pneumoscrotum, and technical defects of laparoscopic instru-

ments or equipment. Cardiovascular complications during sur-

gery were defined as a fall in the diastolic pressure to a level below

50 mm Hg or cardiac arrhythmia. Discontinuation of the original

laparoscopic procedure in favor of either a transperitoneal laparo-

scopic procedure or a conventional procedure was also recorded

as a complication.

6

Postoperatively, all potential complications, such as hematoma,

seroma, chronic pain, and wound infection, were assessed and

documented. A serious wound infection was defined as the pres-

ence of pus or sanguinopurulent discharge at the operative site.

A urinary tract infection or epididymitis was recorded only if an-

tibiotic treatment was prescribed. Urinary retention was defined

as an inability to urinate, requiring catheterization. Postoperative

bleeding was recorded if compression was required to control it.

The length of hospitalization, defined as the number of days in

the hospital after the day of surgery, was also recorded. Patients

were discharged from the hospital if there was no serious infec-

tion or bleeding, the patient was able to walk, and only oral an-

algesic therapy was required to manage pain.

The patients were requested to return to the outpatient clinic

at one and six weeks; at six months; and at one and two years for

a standardized history taking and physical examination by a resi-

dent and, in most cases, by the surgeon who had performed the

surgery. The patients were asked to assess the severity of pain at

the operative site every day for the first week and at two and six

weeks, with the use of a 100-mm visual-analogue scale (scores

ranged from 0, for no pain, to 100, for unbearable pain), and to

record the use of analgesic drugs. Oral analgesia, initially aceta-

minophen (500 mg) or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug, was

given on request. Chronic pain was defined as pain in the groin,

scrotum, or medial part of the thigh that was serious enough for

the patient to mention at six months.

The activities of daily living were assessed with a questionnaire

from a Dutch health survey,

20

modified to include questions ap-

plicable to patients who had undergone inguinal-hernia repairs.

The scale ranged from 0 (worst score) to 100 (best score).

21

The

modified questionnaire was validated in 110 of the patients. The

testretest reliability was 0.89.

21,22

The questionnaire was admin-

istered one day and one, two, and six weeks after surgery. The pa-

tients were also asked to record in a diary the dates on which they

resumed normal daily activity at home, returned to work, and re-

sumed their usual athletic activities.

Since differences in advice about returning to work after in-

guinal hernia repair may affect the validity of this end point,

1,21,23

all study surgeons and other personnel were instructed to give the

same advice about the resumption of work and other activities.

In addition, the patients physicians received a letter explaining

the trial and stating that the patients should not limit their activ-

ities but do whatever they felt able to do.

5,21

All patients were

either visited or contacted by telephone by a member of the cen-

tral study office, who was unaware of the treatment assignments,

soon after discharge to explain the importance of keeping the di-

ary and answer any questions about the follow-up and resump-

tion of usual activities.

Home visits by experienced physicians were also conducted one

and two years postoperatively if patients were unable or did not

want to go to the hospital. Follow-up data were considered com-

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

CONVENTI ONAL ANTERI OR SURGERY VERSUS LAPAROSCOPI C SURGERY FOR I NGUI NAL- HERNI A REPAI R

Vol ume 336 Number 22

1543

plete only if they included the results of follow-up physical exam-

inations by an experienced physician at the planned times.

End Points

The primary end point of the study was a recurrence of the her-

nia, defined as a clinically detectable swelling in the groin or a

clearly palpable defect of the abdominal wall in the groin, diag-

nosed by two physicians. If a physician was unsure whether there

was a recurrence, the physical examination was repeated or ultra-

sonography of the groin was performed.

The main secondary end point was time off from work, defined

as the number of days between the day of surgery and the first

day a patient returned to work, for all patients who were em-

ployed. All deaths were assessed in terms of immediate cause and

the relation of the death to the hernia operation. The resumption

of usual activities, the score on the activities-of-daily-living ques-

tionnaire, postoperative pain, and complications were additional

secondary end points.

Statistical Analysis

In the main analyses, we compared conventional open surgery

and laparoscopic surgery with respect to the interval between sur-

gery and the diagnosis of a recurrence or the return to work. Data

for all patients who were randomly assigned to a treatment group

and underwent surgery were analyzed on an intention-to-treat

basis. In this analysis, we did not include patients without hernias,

those who withdrew their consent before undergoing surgery,

those who at the time of surgery were found to be poor candi-

dates for general anesthesia, and those who did not undergo the

assigned operation because of a misunderstanding resulting in an

unplanned open or laparoscopic repair. No interim analyses were

performed.

Continuous, normally distributed data are expressed as means

SD; other continuous data are expressed as medians with inter-

quartile ranges. For the analysis of differences between groups, we

used two-tailed t-tests or, if the results were not normally distrib-

uted, nonparametric tests. Chi-square or Fishers exact tests were

used to compare proportions. An analysis of variance for repeated

measurements was performed to compare the pain scores for the

two groups. Recurrence-free survival and the time to the resump-

tion of normal activity (i.e., daily home activity, paid work, and

sports) were analyzed with KaplanMeier survival curves, and dif-

ferences between the two treatment groups were compared by

the log-rank test. All reported P values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

We enrolled 1051 patients in the study between

February 1994 and June 1995. During this time,

114 eligible patients were not enrolled: 74 refused

to participate, 27 could not understand the proto-

col, and 13 were not enrolled for a variety of rea-

sons. Of the 1051 enrolled patients, 31 (13 assigned

to the open-surgery group and 18 assigned to the

laparoscopic-surgery group) decided not to undergo

surgery, in most cases because of the absence of se-

rious symptoms. Only three of these patients have

subsequently undergone surgery.

Eighteen patients (8 in the open-surgery group

and 10 in the laparoscopic-surgery group) were ex-

cluded. Three of these patients had bilateral repairs,

four were considered to be poor candidates for gen-

eral anesthesia, and three were found not to have in-

guinal hernias at surgery. An additional eight with-

drew informed consent: two wanted open repairs,

three wanted laparoscopic repairs, two refused annu-

al follow-up, and one underwent surgery at another

hospital. In addition, eight patients did not undergo

the assigned procedure because of a misunderstand-

ing between the central office and the surgeon, with

six of the patients undergoing unplanned open re-

pairs and two undergoing unplanned laparoscopic

repairs.

Hence, our main analysis is based on data from

487 patients who underwent laparoscopic repairs

and 507 who underwent open repairs. Randomiza-

tion was successful, and the two groups were similar

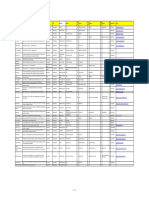

at base line (Table 1). A second analysis of recur-

rence rates included the 8 patients who did not un-

*Plusminus values are means

SD.

ADL denotes activities of daily living.

T

ABLE

1.

B

ASE

-L

INE

C

HARACTERISTICS

OF

994

P

ATIENTS

WITH

I

NGUINAL

H

ERNIAS

R

EPAIRED

WITH

O

PEN

OR

L

APAROSCOPIC

S

URGERY

.*

C

HARACTERISTIC

O

PEN

S

URGERY

(N

507)

L

APAROSCOPIC

S

URGERY

(N

487)

Age yr 55

15 55

16

Sex no. (%)

Male 485 (96) 461 (95)

Female 22 (4) 26 (5)

Height m 1.78

0.08 1.78

0.08

Weight kg 78.0

10.3 77.9

11.8

ADL score

Median

Interquartile range

94

83100

94

83100

Paid work no. (%) 278 (55) 266 (55)

Participation in sports

no. (%)

177 (35) 198 (41)

Primary hernia no. (%) 447 (88) 432 (89)

First recurrent hernia

no. (%)

60 (12) 55 (11)

History of contralateral

hernia no. (%)

14 (3) 28 (6)

Clinical presentation

no. (%)

Swelling in the groin 477 (94) 454 (93)

Discomfort or pain 423 (83) 416 (85)

Coincidental discovery 29 (6) 13 (3)

Potential risk factors for

recurrence no. (%)

Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease

50 (10) 48 (10)

Benign hyperplasia of

the prostate

25 (5) 37 (8)

Constipation 25 (5) 26 (5)

Strenuous activity 122 (24) 103 (21)

Characteristics of hernia

no. (%)

Left-sided 245 (48) 243 (50)

Right-sided 262 (52) 244 (50)

Medial 267 (53) 259 (53)

Lateral 230 (45) 214 (44)

Unknown 10 (2) 13 (3)

Medial and lateral

(pantaloon)

12 (2) 8 (2)

Scrotal 17 (3) 24 (5)

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1544

May 29, 1997

The New Engl and Journal of Medi ci ne

dergo the assigned operation (for a total of 493 pa-

tients in the laparoscopic-surgery group and 509 in

the open-surgery group).

Perioperative and Early Postoperative Results

The mean time from randomization to surgery

was 33

36 days in the open-surgery group and

35

33 days in the laparoscopic-surgery group. In

the open-surgery group, a herniotomy with a high

ligation of the hernial sac was performed in 21 pa-

tients (4 percent). This procedure was combined

with a narrowing of the internal ring with sutures in

44 (9 percent), and a mesh prosthesis was inserted

and a so-called tension-free repair performed in 15

(3 percent). The remaining 427 patients underwent

hernioplasty, with a Bassini technique used in 147

patients (29 percent), a Shouldice technique in 112

(22 percent), a BassiniMcVay technique in 97 (19

percent), a McVay technique in 46 (9 percent), and

various other, less well known techniques in the oth-

er patients. The number of operations per surgeon

ranged from 1 to 33. In the laparoscopic-surgery

group, the range was 1 to 74.

The Nyhus classification of the hernias and the

operative and early postoperative complications in

the two groups are shown in Table 2. The median

duration of surgery was five minutes shorter for the

conventional repair than for the laparoscopic repair.

In the laparoscopic-surgery group, an open proce-

dure was used in 20 patients and a transabdominal

preperitoneal laparoscopic procedure was used in

4 (Table 3). During laparoscopic surgery, 115 pa-

tients (24 percent) had peritoneal tears, but in only

8 of these patients (7 percent) did the tear result in

loss of pneumopreperitoneum, requiring a switch to

another technique. In 15 patients (3 percent), the

epigastric vessels were ligated because they blocked

the view of the surgeon; in 2 patients, these vessels

were ligated after being injured during the insertion

of a trocar. After surgery, 64 patients had a pneumo-

scrotum (13 percent), which disappeared within one

day in all but 3 patients (Table 2). The most severe

postoperative complications were serious wound in-

fections in six patients in the open-surgery group

(Table 2); two of these patients had to be rehospi-

talized.

Postoperative Recovery

The visual-analogue pain scores after surgery were

lower in the laparoscopic-surgery group than in the

open-surgery group (P

0.001), although the differ-

ence diminished with time (Fig. 1). Seventeen pa-

tients in the laparoscopic-surgery group and 27 in

the open-surgery group did not record pain scores;

complete data were available for 90 percent of the

patients. On the day of surgery, 288 patients (59

percent) in the laparoscopic-surgery group did not

require any analgesic drugs for postoperative pain, as

compared with 165 patients (33 percent) in the

open-surgery group. The proportions of patients

not requiring analgesia were 88 and 82 percent, re-

spectively, at one week and 92 and 91 percent, re-

spectively, at six weeks.

The patients in the laparoscopic-surgery group

were able to resume normal activity sooner than the

patients in the open-surgery group (Table 4). Scores

*Type I is an indirect hernia with a normal internal abdominal ring. Type

II is an indirect hernia with an enlarged and distorted internal abdominal

ring and an intact posterior wall. Type III is a hernia with a posterior-wall

defect (A, direct; B, indirect [also pantaloon or scrotal]; or C, femoral).

Type IV is a recurrent hernia (A, direct; B, indirect [also pantaloon]; or

C, femoral).

T

ABLE

2.

C

HARACTERISTICS

OF

S

URGERY

AND

O

PERATIVE

AND

E

ARLY

P

OSTOPERATIVE

C

OMPLICATIONS

.

CHARACTERISTIC

OPEN SURGERY

(N507)

LAPAROSCOPIC

SURGERY

(N487)

P

VALUE

Operation time min

Median

Interquartile range

40

3045

45

3560

0.001

no. of patients (%)

Anesthesia

General 201 (40) 481 (99)

Spinal 306 (60) 6 (1)

Prophylactic antibiotics 16 (3) 7 (1)

Nyhus classification*

Type I 45 (9) 25 (5)

Type II 129 (25) 199 (41)

Type III

A 121 (24) 95 (20)

B 151 (30) 113 (23)

C 1 (1) 0

Type IV

A 36 (7) 24 (5)

B 23 (5) 30 (6)

C 1 (1) 0

Operative complications

Switch to another surgical

technique

24 (5)

Cardiovascular complica-

tions

1 (1) 2 (1) 0.62

Vas deferens injury 1 (1) 1 (1) 1.00

Arterial bleeding (clips or

ligatures required)

2 (1) 7 (1) 0.10

Balloon rupture during

dissection

6 (1)

Use of extra trocar 2 (1)

Broken instruments 0 2 (1) 0.24

Postoperative complications

Related death 0 0

Serious wound infection

(abscess)

6 (1) 0 0.03

Wound infection requiring

rehospitalization

2 (1) 0 0.50

Urinary tract infection 2 (1) 1 (1) 1.0

Epididymitis 2 (1) 3 (1) 0.68

Urinary retention 2 (1) 5 (1) 0.28

Bleeding 1 (1) 1 (1) 1.00

Chronic pain 70 (14) 10 (2) 0.001

Hematoma at 6 weeks 14 (3) 24 (5) 0.07

Seroma at 6 weeks 0 7 (1) 0.007

Pneumoscrotum at dis-

charge from hospital

3 (1)

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

CONVENTI ONAL ANTERI OR SURGERY VERSUS LAPAROSCOPI C SURGERY FOR I NGUI NAL- HERNI A REPAI R

Vol ume 336 Number 22 1545

on the activities-of-daily-living questionnaire, which

were available for 98 percent of the patients, were

higher in the laparoscopic-surgery group at all times.

Complications and Recurrences

The median follow-up was 607 days (interquartile

range, 369 to 731). Recurrences were diagnosed in

31 patients (6 percent) in the open-surgery group

and 17 (3 percent) in the laparoscopic-surgery group

(P0.05) (Fig. 2). There were 11 deaths in the

open-surgery group and 6 in the laparoscopic-sur-

gery group, all of which were unrelated to the hernia

operation. All but 32 patients (3 percent) were ex-

amined in 1996.

Among the 17 patients in the laparoscopic-sur-

gery group who had recurrences, 10 (59 percent)

were operated on by surgeons who had just begun

to perform the operation independently. Six of these

10 patients were operated on by one surgeon, and

3 of his subsequent patients had recurrences. Four-

teen of the 17 recurrences (82 percent) in this group

occurred within the first year after surgery, whereas

in the open-surgery group 15 recurrences were di-

agnosed during the first year after surgery, and 16

during the second year. All but 12 of the 48 patients

with recurrences subsequently underwent additional

surgery, at which time the recurrence was con-

firmed.

The difference in the rates of recurrence between

the two groups was similar (P0.05) when the eight

patients who did not undergo the assigned operation

were included in the analysis.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that patients

with inguinal hernias recover more rapidly and have

fewer recurrences after laparoscopic repair than after

open repair. The duration of surgery was only slight-

ly longer (five minutes) with laparoscopic repair, pro-

viding little support for the widespread belief that

this procedure is more time-consuming than open

surgery. Nearly all the laparoscopic operations were

performed with general anesthesia, whereas 60 per-

cent of the open operations were performed with

spinal anesthesia. The use of general anesthesia might

be considered a disadvantage of laparoscopic repair.

Nevertheless, the patients in the laparoscopic-sur-

gery group were discharged from the hospital soon-

er and had less early and late postoperative pain than

the patients in the open-surgery group.

The difference in the rates of recurrence in the

two groups would appear to be clinically important.

With prolonged follow-up, more recurrences may be

expected in the open-surgery group,

9

and these late

recurrences may be prevented only by reinforcing

the groin region with additional support.

24

A late re-

currence after laparoscopic surgery may be uncom-

mon because mesh is used routinely to reinforce the

groin region from inside. The rationale for covering

the defect in the abdominal wall with mesh from in-

side is that the repair can better withstand the pres-

sure to which it is subjected, which originates inside

the abdomen.

25

The difference in recurrence rates in

the two groups can therefore be expected to increase

over time.

Early recurrences in general may be caused by

*TAPP denotes transabdominal preperitoneal lap-

aroscopy.

TABLE 3. REASONS FOR A SWITCH TO ANOTHER

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE DURING

LAPAROSCOPIC REPAIR IN 24 PATIENTS.

REASON TECHNIQUE USED

CONVEN-

TIONAL TAPP*

no. of patients

Loss of pneumopreperitoneum 6 2

Adhesions 3 2

Intubation impossible 2

Inadequate light 2

Arterial bleeding 2

Scrotal hernia 2

Hernial defect too large 1

Too much adipose tissue 1

Pain during spinal anesthesia 1

Figure 1. Mean (SE) Visual-Analogue Scores for Postopera-

tive Pain on the Day of Surgery, during the First 7 Days after

Surgery, and at 14 and 42 Days in Patients with Inguinal Herni-

as Repaired with Open or Laparoscopic Surgery.

A score of 0 denotes no pain, and a score of 100 unbearable

pain. Postoperative pain was less severe in the laparoscopic-

surgery group (P0.001).

0

100

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 42

80

60

40

20

Postoperative Day

V

i

s

u

a

l

-

A

n

a

l

o

g

u

e

P

a

i

n

S

c

o

r

e

Open surgery

Laparoscopic surgery

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1546 May 29, 1997

The New Engl and Journal of Medi ci ne

technical errors.

26

All but three recurrences in the

laparoscopic-surgery group occurred within one year

after surgery, and in most cases, the patients had lat-

eral hernias that had been overlooked. Insufficient

lateral preperitoneal dissection, resulting in furled

mesh, was another common mistake.

18

Ten of the re-

currences were in patients operated on by surgeons

who had limited experience with the laparoscopic

procedure, and a single surgeon was responsible for

9 of the 17 recurrences. These findings clearly illus-

trate the danger of underestimating the skill and ex-

perience required to master this technique.

Physical examination during follow-up is indis-

pensable for obtaining reliable data on rates of re-

currence, because follow-up by telephone or mail is

unreliable.

4,7,8

Virtually all our patients (97 percent)

had follow-up physical examinations performed by

two experienced physicians, who made home visits

to patients unable or unwilling to come to the hos-

pital for follow-up. Although others

4,7,27

have recog-

nized the importance of physical examination after

hernia repair, the percentages of patients examined

during follow-up have usually been lower than in

our study.

The patients returned to work sooner after laparo-

scopic repair than after open repair, as reported in

several smaller trials.

8,15

In our study, the difference

was appreciable (a median of seven days). This differ-

ence may be explained by the absence of an inguinal

incision, the absence of dissection of muscle in the

groin during laparoscopic repair, and the tension-free

repair, as well as by the lower complication rate.

It may be argued that a small group of surgeons

who are interested in a particular procedure will al-

ways perform better than those who do not have this

special interest and that different levels of experience

should be taken into account when comparing our

two groups of surgeons. Our surgeons were selected

broadly, and the initial errors made by several of them

indicate that they were not highly experienced. With-

in the group performing laparoscopic repairs and

within the group performing conventional repairs,

there were different levels of experience and skill.

Finally, the hospitals in our study were selected to

obtain a representative cross-section of patients and

surgeons in the Netherlands. This pragmatic approach

may provide an answer to the question of whether

the Dutch surgical community is capable of achiev-

ing better results overall with a laparoscopic ap-

proach than with the open approach currently used.

The results of our trial will be used by the govern-

ment to decide whether laparoscopic repair of in-

guinal hernias should be included as a reimbursable

procedure in our health care system. Given the su-

perior results of laparoscopic repair in terms of re-

covery and recurrence rates over time, and with the

lessons of the learning curve kept in mind, a gradual

introduction of laparoscopic hernia repair on a large

scale seems warranted, but only if the procedure is

supervised by experienced surgeons.

Supported by a grant (OG/011) from the Dutch Ministry of Health,

Welfare, and Sports.

*P0.001 for all comparisons.

ADL denotes activities of daily living.

TABLE 4. POSTOPERATIVE RECOVERY IN THE TWO

TREATMENT GROUPS.*

VARIABLE

OPEN

SURGERY

LAPAROSCOPIC

SURGERY

median (interquartile range)

Postoperative hospital stay

(days)

2 (12) 1 (12)

Time to resumption of

normal activity (days)

10 (616) 6 (410)

Time to return to work (days) 21 (1233) 14 (721)

Time to resumption of

athletic activities (days)

36 (2444) 24 (1438)

ADL score

At 1 day 39 (2256) 50 (3367)

At 1 week 72 (5683) 83 (7294)

At 2 weeks 83 (7294) 94 (83100)

At 6 weeks 83 (7294) 94 (83100)

Figure 2. KaplanMeier Curves for Recurrence-free Survival in

the Open-Surgery and Laparoscopic-Surgery Groups.

The median follow-up was 607 days (interquartile range, 369 to

731). The P value for the difference in the rates of recurrence

between the two groups was 0.05 by the log-rank test.

84

0

100

0 300 1200

96

92

88

600 900

Days after Surgery

P

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

F

r

e

e

o

f

R

e

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

e

s

(

%

)

NO. OF PATIENTS AT RISK

Laparoscopic surgery

Open surgery

Laparoscopic

surgery

Open

surgery

455

463

252

248

9

14

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

CONVENTI ONAL ANTERI OR SURGERY VERSUS LAPAROSCOPI C SURGERY FOR I NGUI NAL- HERNI A REPAI R

Vol ume 336 Number 22 1547

We are indebted to the surgeons, residents, and staff at St. Clara

Hospital, Diakonessenhuis, Hofpoort Hospital, Ikazia Hospital,

Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, and University Hospital Utrecht for

their help with this study; to Ms. C.G.M.M. Beckers, Ms. I.G.M. An-

nink, Ms. A.D.M. Schyns, and Drs. R.C. Zwart, I. Geurts, and

J.J.M. Heyligers of the Conventional Anterior versus Laparoscopic

Hernia Repair (COALA) Trial Office for data management and

secretarial support; to Drs. L.S. de Vries and I.M.C. Janssen for their

collaboration at the beginning of the trial; and to all our patients

for their willingness to participate in the study.

REFERENCES

1. Rider MA, Baker DM, Locker A, Fawcett AN. Return to work after in-

guinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 1993;80:745-6.

2. Salcedo-Wasicek MC, Thirlby RC. Postoperative course after herniorrha-

phy: a case-controlled comparison of patients receiving workers compensa-

tion vs. patients with commercial insurance. Arch Surg 1995;130:29-32.

3. Dutch Center for Health Care Information. Annual computer disk of

the hospitals, the annual of the hospitals. Utrecht, the Netherlands: SIG

Zorginformatie, 1995 (software). (In Dutch.)

4. Schumpelick V, Treutner KH, Arlt G. Inguinal hernia repair in adults.

Lancet 1994;344:375-9.

5. Shulman AG, Amid PK, Lichtenstein IL. Returning to work after her-

niorrhaphy: take it easy is the wrong advice. BMJ 1994;309:216-7.

6. Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Kerbl K. Laparoscopic general surgery. N Engl J

Med 1994;330:409-19.

7. Hay J-M, Boudet M-J, Fingerhut A, et al. Shouldice inguinal hernia re-

pair in the male adult: the gold standard? A multicenter controlled trial in

1578 patients. Ann Surg 1995;222:719-27.

8. Liem MSL, van Vroonhoven TJMV. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair.

Br J Surg 1996;83:1197-204.

9. Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK. The cause, prevention,

and treatment of recurrent groin hernia. Surg Clin North Am 1993;73:

529-44.

10. McKernan JB, Laws HL. Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias using

a totally extraperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg Endosc 1993;7:26-8.

11. Felix EL, Michas CA, Gonzales MH Jr. Laparoscopic hernioplasty:

TAPP vs. TEP. Surg Endosc 1995;9:984-9.

12. Stoker DL, Spiegelhalter DJ, Singh R, Wellwood JM. Laparoscopic

versus open inguinal hernia repair: randomised prospective trial. Lancet

1994;343:1243-5.

13. Payne JH Jr, Grininger LM, Izawa MT, Podoll EF, Lindahl PHJ, Bal-

four J. Laparoscopic or open inguinal herniorrhaphy? A randomized pro-

spective trial. Arch Surg 1994;129:979-81.

14. Vogt DM, Curet MJ, Pitcher DE, Martin DT, Zucker KA. Preliminary

results of a prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic onlay versus con-

ventional inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 1995;169:84-90.

15. Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Goodwin A, et al. Randomised controlled

trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: early results. BMJ

1995;311:981-5.

16. Barkun JS, Wexler MJ, Hinchey EJ, Thibeault D, Meakins JL. Laparo-

scopic versus open inguinal herniorrhaphy: preliminary results of a ran-

domized controlled trial. Surgery 1995;118:703-10.

17. Age distribution per municipality, 1 January 1994. Mndstat Bevolk

(CBS) 1994;10:24-32. (In Dutch.)

18. Liem MSL, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, et al. The learning curve

for totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg

1996;171:281-5.

19. Nyhus LM. Individualization of hernia repair: a new era. Surgery

1993;114:1-2.

20. Picavet HSJ, van Sonsbeek JLA, van den Bos GAM. Health interview

surveys, the measurement of functional disabilities in the elderly by surveys.

Mndber Gezond (CBS) 1992;7:5-20. (In Dutch.)

21. Liem MSL, van der Graaf Y, Zwart RC, Geurts I, van Vroonhoven

TJMV. A randomized comparison of physical performance following lap-

aroscopic and open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 1997;84:64-7.

22. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical

guide to their development and use. Oxford, England: Oxford University

Press, 1989.

23. Activity and recurrent hernia. BMJ 1977;2:3-4.

24. Lichtenstein IL, Shore JM. Exploding the myths of hernia repair. Am

J Surg 1976;132:307-15.

25. Stoppa RE. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias.

World J Surg 1989;13:545-54.

26. Peacock EE Jr, Madden JW. Studies on the biology and treatment of

recurrent inguinal hernia. II. Morphological changes. Ann Surg 1974;179:

567-71.

27. Iles JDH. Specialisation in elective herniorrhaphy. Lancet 1965;1:751-

5.

MASSACHUSETTS MEDICAL SOCIETY REGISTRY ON CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

To obtain information about continuing medical education courses in New England, call

between 9 a.m. and 12 noon, Monday through Friday, (617) 893-4610, or in Massachusetts,

1-800-322-2303, ext. 1342.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on April 19, 2013. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

También podría gustarte

- Family Medicine Board Review - Pass Your ABFM Exam - CMEDocumento6 páginasFamily Medicine Board Review - Pass Your ABFM Exam - CMEa jAún no hay calificaciones

- Kelantan Obstetrics Shared Care Guideline Finale1 10 3Documento100 páginasKelantan Obstetrics Shared Care Guideline Finale1 10 3JashveerBedi0% (1)

- RCM: Revenue Cycle Management in HealthcareDocumento15 páginasRCM: Revenue Cycle Management in Healthcaresenthil kumar100% (5)

- Conservative Management of Perforated Peptic UlcerDocumento4 páginasConservative Management of Perforated Peptic UlcerAfiani JannahAún no hay calificaciones

- Hernia IngunalisDocumento7 páginasHernia IngunalisAnggun PermatasariAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDocumento6 páginasLaparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDamal An NasherAún no hay calificaciones

- Corto y Largo PlazoDocumento6 páginasCorto y Largo PlazoElard Paredes MacedoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reoperation For Dysphagia After Cardiomyotomy For Achalasia: Clinical Surgery-InternationalDocumento5 páginasReoperation For Dysphagia After Cardiomyotomy For Achalasia: Clinical Surgery-Internationalgabriel martinezAún no hay calificaciones

- Vrijland Et Al-2002-British Journal of SurgeryDocumento5 páginasVrijland Et Al-2002-British Journal of SurgeryTivHa Cii Mpuzz MandjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Documento5 páginasLaparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Juan Carlos SantamariaAún no hay calificaciones

- Perbedaan Penanganan Antara Laparoskopi Vs Open Repair Pada Perforasi GasterDocumento7 páginasPerbedaan Penanganan Antara Laparoskopi Vs Open Repair Pada Perforasi GasterAfiani JannahAún no hay calificaciones

- Nah Incarcerated HerniaDocumento4 páginasNah Incarcerated Herniafelix_the_meowAún no hay calificaciones

- Utd 04524 Clinical - Article KunduzDocumento5 páginasUtd 04524 Clinical - Article Kunduzzenatihanen123Aún no hay calificaciones

- Isj-5899 oDocumento5 páginasIsj-5899 oAbhiram MundleAún no hay calificaciones

- Stapled Rectal Mucosectomy vs. Close HemorrhoidectomyDocumento9 páginasStapled Rectal Mucosectomy vs. Close HemorrhoidectomyNadllely Garcia ZapataAún no hay calificaciones

- 268 2011 Article 1088 PDFDocumento6 páginas268 2011 Article 1088 PDFIoel Tovar TrovaAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Study: Delorme's Procedure For Complete Rectal Prolapse: A Study of Recurrence Patterns in The Long TermDocumento6 páginasClinical Study: Delorme's Procedure For Complete Rectal Prolapse: A Study of Recurrence Patterns in The Long TermAnonymous A1ycUQ9zVIAún no hay calificaciones

- Apendisitis MRM 3Documento8 páginasApendisitis MRM 3siti solikhaAún no hay calificaciones

- VolvulusDocumento10 páginasVolvuluswatsonmexAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Surgery For DiverticulitisDocumento4 páginasLaparoscopic Surgery For DiverticulitisSigit SetiaWanAún no hay calificaciones

- Conventional Versus Laparoscopic Surgery For Acute AppendicitisDocumento4 páginasConventional Versus Laparoscopic Surgery For Acute AppendicitisAna Luiza MatosAún no hay calificaciones

- Incisional Hernia Mesh RepairDocumento5 páginasIncisional Hernia Mesh Repaireka henny suryaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic vs Open Colorectal Cancer SurgeryDocumento7 páginasShort- and Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic vs Open Colorectal Cancer SurgeryRegina SeptianiAún no hay calificaciones

- @medicinejournal European Journal of Pediatric Surgery January 2020Documento126 páginas@medicinejournal European Journal of Pediatric Surgery January 2020Ricardo Uzcategui ArreguiAún no hay calificaciones

- qt5kh1c39r NosplashDocumento12 páginasqt5kh1c39r NosplashSusieAún no hay calificaciones

- Brown 2014Documento8 páginasBrown 2014nelly alconzAún no hay calificaciones

- The Learning Curve For Hernia PDFDocumento5 páginasThe Learning Curve For Hernia PDFIgor CemortanAún no hay calificaciones

- Bun V34N3p223Documento6 páginasBun V34N3p223pingusAún no hay calificaciones

- Palliative Management of Malignant Rectosigmoidal Obstruction. Colostomy vs. Endoscopic Stenting. A Randomized Prospective TrialDocumento4 páginasPalliative Management of Malignant Rectosigmoidal Obstruction. Colostomy vs. Endoscopic Stenting. A Randomized Prospective TrialMadokaDeigoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDocumento8 páginasReoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDiego Andres VasquezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Incidence and Risk of Early Postoperative Small Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Resection For Colorectal Cancer 2014Documento7 páginasThe Incidence and Risk of Early Postoperative Small Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Resection For Colorectal Cancer 2014alemago90Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerDocumento9 páginasA Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerFarizka Dwinda HAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Versus Open Transhiatal Esophagectomy For Distal and Junction CancerDocumento6 páginasLaparoscopic Versus Open Transhiatal Esophagectomy For Distal and Junction CancerDea Melinda SabilaAún no hay calificaciones

- Esposito 2006Documento4 páginasEsposito 2006Fernando GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Bjs 10662Documento8 páginas1 Bjs 10662Vu Duy KienAún no hay calificaciones

- Mid-Term Pneumatic Dilatation for AchalasiaDocumento3 páginasMid-Term Pneumatic Dilatation for AchalasiaLuis PerazaAún no hay calificaciones

- Recurrent Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction Following Primary Treatment: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Laparoscopic TreatmentDocumento9 páginasRecurrent Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction Following Primary Treatment: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Laparoscopic TreatmentPatricio G.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Monitoring Complications of MeDocumento8 páginasMonitoring Complications of Meaxl___Aún no hay calificaciones

- Umesh Singh. TLTK-47Documento5 páginasUmesh Singh. TLTK-47HẢI HOÀNG THANHAún no hay calificaciones

- Bariatric SurgeryDocumento4 páginasBariatric SurgeryCla AlsterAún no hay calificaciones

- DTSCH Arztebl Int-115 0031Documento12 páginasDTSCH Arztebl Int-115 0031Monika Diaz KristyanindaAún no hay calificaciones

- Management of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive TreatmentDocumento5 páginasManagement of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive Treatmentapi-308365861Aún no hay calificaciones

- Jo (2003)Documento5 páginasJo (2003)Елена КарпинскаяAún no hay calificaciones

- emil2006Documento5 páginasemil2006mia widiastutiAún no hay calificaciones

- Complicated AppendicitisDocumento4 páginasComplicated AppendicitisMedardo ApoloAún no hay calificaciones

- Protocol oDocumento8 páginasProtocol oCynthia ChávezAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Vagotomy for Chronic Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocumento4 páginasLaparoscopic Vagotomy for Chronic Peptic Ulcer Diseasepeter_mrAún no hay calificaciones

- Hernia Jur Nal 2000Documento12 páginasHernia Jur Nal 2000Hevi Eka TarsumAún no hay calificaciones

- Frazee 2016Documento10 páginasFrazee 2016Herpian NugrahadilAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy PDFDocumento4 páginasLaparoscopic Appendectomy PDFdydydyAún no hay calificaciones

- Inguinal HerniaDocumento9 páginasInguinal HerniaAmanda RapaAún no hay calificaciones

- Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Propensity Score Matching AnalysisDocumento10 páginasLaparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Propensity Score Matching AnalysisFerdian PriantoAún no hay calificaciones

- Surgical Outcome of Genito Urinary Fistula - RayazDocumento3 páginasSurgical Outcome of Genito Urinary Fistula - RayazRiaz Ahmed ChaudhryAún no hay calificaciones

- Closure Vs Nonclosure of PeritoneumDocumento6 páginasClosure Vs Nonclosure of PeritoneumFrancisco Xavier Beltrán Vallejo100% (1)

- Bar Dram 2000Documento6 páginasBar Dram 2000Prasetyö AgungAún no hay calificaciones

- General Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueDocumento3 páginasGeneral Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueRahul SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Enhanced Recovery Protocol After Ileostomy ReversalDocumento4 páginasEnhanced Recovery Protocol After Ileostomy Reversalshah hassaanAún no hay calificaciones

- PICO InvaginasiDocumento4 páginasPICO InvaginasimutimutimutiAún no hay calificaciones

- A Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisDocumento5 páginasA Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisBenjamin PaulinAún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyDocumento10 páginasImpact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyPutri PadmosuwarnoAún no hay calificaciones

- Damage Control in Trauma Care: An Evolving Comprehensive Team ApproachDe EverandDamage Control in Trauma Care: An Evolving Comprehensive Team ApproachJuan DuchesneAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Studies of Postoperative Complications after Digestive SurgeryDe EverandCase Studies of Postoperative Complications after Digestive SurgeryAún no hay calificaciones

- The SAGES Manual of Biliary SurgeryDe EverandThe SAGES Manual of Biliary SurgeryHoracio J. AsbunAún no hay calificaciones

- Kawasaki CPD Online 2014Documento47 páginasKawasaki CPD Online 2014'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- GigiDocumento10 páginasGigiIsmail Eko SaputraAún no hay calificaciones

- GNAPS Online Simpo Rev 2Documento19 páginasGNAPS Online Simpo Rev 2chlorooAún no hay calificaciones

- Hubungan Kepribadian Tipe D Dengan Kejadian HipertensiDocumento4 páginasHubungan Kepribadian Tipe D Dengan Kejadian HipertensiS'Herlina Ali SopiahAún no hay calificaciones

- Cutaneous Tuberculosis in Children PDFDocumento10 páginasCutaneous Tuberculosis in Children PDFMeryam SetiawanAún no hay calificaciones

- Chronic Migrainous VertigoDocumento5 páginasChronic Migrainous VertigoDyah Wulan RamadhaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Hemoroid LigationDocumento6 páginasHemoroid Ligation'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- STROKE HEMORAGIKDocumento20 páginasSTROKE HEMORAGIKFebrita PutriAún no hay calificaciones

- JurnalDocumento6 páginasJurnal'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- Overview Dermatitis AtopiDocumento9 páginasOverview Dermatitis Atopi'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- Cutaneous Tuberculosis in Children PDFDocumento10 páginasCutaneous Tuberculosis in Children PDFMeryam SetiawanAún no hay calificaciones

- 2013 Sa64 PDFDocumento13 páginas2013 Sa64 PDF'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- Overview Dermatitis AtopiDocumento9 páginasOverview Dermatitis Atopi'Muhamad Rofiq Anwar'Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hand Expressing Breast PubmedDocumento15 páginasHand Expressing Breast PubmedAsri HartatiAún no hay calificaciones

- The Pharmacist's Guide To Evidence-Based MedicineDocumento2 páginasThe Pharmacist's Guide To Evidence-Based MedicineDhanang Prawira NugrahaAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Dental Hygiene II 2021-2022 Course CatalogDocumento2 páginasClinical Dental Hygiene II 2021-2022 Course Catalogapi-599847268Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nutritional Content and Health Benefits of EggplantDocumento6 páginasNutritional Content and Health Benefits of Eggplantdhanashri pawarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Amazing Science of AuriculotherapyDocumento26 páginasThe Amazing Science of AuriculotherapyNatura888100% (13)

- Crma Unit 1 Crma RolesDocumento34 páginasCrma Unit 1 Crma Rolesumop3plsdn0% (1)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines On The Management of ChildrenDocumento17 páginasClinical Practice Guidelines On The Management of ChildrenRajithaHirangaAún no hay calificaciones

- Intensive-Care Unit: TypesDocumento2 páginasIntensive-Care Unit: TypesRavi KantAún no hay calificaciones

- Handbook On ICMR Ethical GuidelinesDocumento28 páginasHandbook On ICMR Ethical Guidelinessamkarmakar2002Aún no hay calificaciones

- Orthopedics P - Iv June15 PDFDocumento2 páginasOrthopedics P - Iv June15 PDFPankaj VatsaAún no hay calificaciones

- Name Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailDocumento8 páginasName Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailshrutiAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of Depression Among Students in Iplc Senior High School-1Documento3 páginasThe Impact of Depression Among Students in Iplc Senior High School-1Roxanne TongcuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Exercise in PregnancyDocumento7 páginasExercise in PregnancynirchennAún no hay calificaciones

- AFOMP Newsletter January 2022 Vol14 No.1 UpdatedDocumento48 páginasAFOMP Newsletter January 2022 Vol14 No.1 UpdatedparvezAún no hay calificaciones

- DR Avijit Bansal-My Experiences at UCMSDocumento6 páginasDR Avijit Bansal-My Experiences at UCMScholesterol200Aún no hay calificaciones

- Myocardial Infarction Case StudyDocumento9 páginasMyocardial Infarction Case StudyMeine Mheine0% (1)

- Danielle Nesbit: Work ExperienceDocumento4 páginasDanielle Nesbit: Work ExperienceNav SethAún no hay calificaciones

- Nutritional Needs of A Newborn: Mary Winrose B. Tia, RNDocumento32 páginasNutritional Needs of A Newborn: Mary Winrose B. Tia, RNcoosa liquorsAún no hay calificaciones

- Ap2 Safe ManipulationDocumento5 páginasAp2 Safe ManipulationDarthVader975Aún no hay calificaciones

- Donning A Sterile Gown and GlovesDocumento3 páginasDonning A Sterile Gown and GlovesVanny Vien JuanilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Barriers To NP Practice That Impact Healthcare RedesignDocumento15 páginasBarriers To NP Practice That Impact Healthcare RedesignMartini ListrikAún no hay calificaciones

- Motivation Letter - EmboDocumento1 páginaMotivation Letter - EmboFebby NurdiyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Altitude SicknessDocumento2 páginasAltitude Sicknessapi-367386863Aún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Pharmacology Answers 2022Documento223 páginasClinical Pharmacology Answers 2022nancy voraAún no hay calificaciones

- StiDocumento12 páginasStiValentinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cholelithiasis N C P BY BHERU LALDocumento1 páginaCholelithiasis N C P BY BHERU LALBheru LalAún no hay calificaciones

- 7-Postoperative Care and ComplicationsDocumento25 páginas7-Postoperative Care and ComplicationsAiden JosephatAún no hay calificaciones