Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Electric Bass Guitar - A Rockabilly Perspective

Cargado por

Diana Negroiu0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

294 vistas17 páginasThis article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Descripción original:

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoThis article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

294 vistas17 páginasElectric Bass Guitar - A Rockabilly Perspective

Cargado por

Diana NegroiuThis article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 17

This article was downloaded by: [Birmingham City University]

On: 04 May 2014, At: 15:36

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Popular Music and Society

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20

The Appearance of the Electric Bass

Guitar: A Rockabilly Perspective

Roy C. Brewer Freelance Musician and PartTime Lecturer

a

a

University of Oregon

Published online: 17 May 2010.

To cite this article: Roy C. Brewer Freelance Musician and PartTime Lecturer (2003) The

Appearance of the Electric Bass Guitar: A Rockabilly Perspective, Popular Music and Society, 26:3,

351-366, DOI: 10.1080/0300776032000116996

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0300776032000116996

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or

arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-

and-conditions

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2003

ISSN0300-7766 print/ISSN 1740-1712 online/03/030351-16 2003 Taylor & Francis Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/0300776032000116996

The Appearance of the Electric Bass

Guitar: A Rockabilly Perspective

Roy C. Brewer

Introduction

When listening to recordings from the first period of rockabillythat is, before

Elvis Presleys move to RCA Records in 1956it is obvious that the acoustic bass

played a major role in the sonic construction of the genre. The frenzied quality of

Presleys recordings from Sun Studio, for example, is as much due to the slapping

sound of Bill Blacks upright bass as to Presleys insolent vocal style. The musical

energy provided by the physical abuse of the acoustic bass helped propel the

raucous style and aroused a new sense of urgency in popular music. The fierce

approach to playing rockabilly bass and the traitorous disrespect to the cultural

traditions it represented were undeniably the roots of later rock and roll styles. By

the late 1950s, as rockabilly disseminated in to other popular musical styles, that

frenzied quality supplied by the upright bass was lost as the use of the electric

bass became more popular.

1

Arrangements for songs such as WalkDont Run,

by the Ventures in 1960, use the electric bass guitar in new parallel movement with

the electric guitars.

There has been a continuing debate about the influence of technology on the

sound and purpose of popular music, particularly those musics of ethnic origin.

There is little doubt that the rockabilly revival of the late 1970s and 1980s was

a response, albeit indirectly and probably unconsciously, to the new wave

of synthesizer-dominated pop music of that era. There is now a flourishing

rockabilly movement in the smaller rock and roll venues in the United States and

Western Europe, and also a new demand for the pioneers of rockabilly to perform.

In these deliberately historical performances of authentic rockabilly, the acoustic

bass has found a new home. We can now, in hindsight, view 1950s rockabilly and

its aftermath as a case study of the effects of technology, the electric bass guitar in

particular, on American popular music. Rockabilly helped standardize instrumen-

tation in the pop ensemble and ultimately changed the sonic character of rock

and roll and the direction it would take in the 1960s and 1970s. Amplification

of the vocal, guitar, and eventually bass, in both white and black roots music,

indeed altered the relationship between sound and sight during performances

and became an integral part of the music process and expectations of listeners

(Waksman 12949).

Although their construction is similar, the histories of the electric bass and

the electric guitar are surprisingly different. The electric guitar, for example,

entered popular music much more gradually. As early as 1932, Rickenbacker had

developed an amplified guitar, and, by 1940, retro fitting pickups were available

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

352 Brewer

on the market. So long before the early 1950s, when Leo Fender created his solid-

bodied Broadcaster and Gibson developed the Les Paul model, the electric guitar

had begun a period of assimilation in to vernacular musical styles. By 1954,

electric guitarists had been influenced by the swinging low-string styles of Arthur

Guitar Boogie Smith, single-note solo passages by Hank Williamss Sammy

Pruett, and the finger-picking styles of Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. Rockabilly

electric guitarists were also influenced by performers in R&B, who adopted the

instrument at a surprisingly early date. Then, towards the end of the 1950s, pro-

mising performers such as Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran in white rock, and Bo

Diddley and Chuck Berry in black rock, solidified the image of the electric guitar

in rock and roll for the performers of the 1960s (Waksman 162). But in rockabilly,

the lead singer seldom played electric guitar. Those who followed Elvis Presleys

economical prototype instrumentation, which was based upon standards of

instrumentation developed in country music (acoustic guitar, electric guitar,

acoustic bass), delegated the electric guitar lines to a sideman. There are, of course,

a handful of exceptions to the pattern, such as Carl Perkins and Roy Orbison, but

generally the rockabilly singer played, or at least held, an acoustic guitar rather

than an electric.

2

It is difficult to look at the dramatic changes within the short rockabilly era and

not conclude that the relatively sudden displacement of the acoustic bass from

the style had some role in what has been viewed as a homogenization of rock and

roll in the late 1950s. The visual image of the acoustic bass being abused by the

rockabilly player and the subsequent racket it produced were essential elements to

rockabilly. After the popularity of tame teen idols in the early 1960s, musicians of

the British invasion rediscovered and increased the rebellious nature and frenetic

qualities of rockabilly and R&B.

3

The post-rockabilly era also was a time for the

standardization of instrumentation in the rock and roll ensemble through the

success of instrumental hits. The earliest image of the electric bass guitarist was

finally defined in 1964 by the Beatles Paul McCartney, who played a 1963 Hofner

model 500/1 shaped much like an upright bass.

The acoustic bass

It is important to this study to address the unique sonic properties of the acous-

tic bass and to be able to achieve a clear comparison with the electric bass guitar.

Undoubtedly, individual timbre and volume will differ according to the construc-

tion and quality of the particular acoustic bass, but, nonetheless, the upright bass

has certain inherent qualities and physical limitations that encouraged the inven-

tion of the electric bass and its subsequent adoption by a majority of vernacular

musicians.

The acoustic bass, also known as double bass, string bass, upright bass, and

bull fiddle, has been played in European art music for centuries. While it is com-

monly included as the lowest pitched instrument in the European string family, it

is actually a descendent of the viol group (Clevinger). So, originally, the upright

bass was meant to be bowed. The bowing technique of sound production allowed

a variety of staccato and legato tones, and more resonance and volume. The

fact that the bass was primarily a plucked instrument in the vernacular world

probably played a part in its being replaced by the electric bass guitar.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 353

The bass has been included in ensembles for American vernacular music since

the ragtime orchestras and string bands of the 1890s, when it was commonly used.

Although the acoustic bass was used in live performances, the tuba, which was

easier to record, was often a substitute in the early recordings of jazz and other

music in the 1920s. Nevertheless, as jazz moved away from its New Orleans brass

band roots, the plucked bass gradually became the standard harmonic instrument

in the rhythm sections of early big bands in the late 1920s. As the size of ensembles

grew between the 1930s and 1950s, the collective sonic volume was raised. Conse-

quently, the acoustic bass became difficult to hear during both live and recording

situations. It is no wonder that Duke Ellington used two bassists simultaneously

in his swing band lineup of 1934, and that symphony orchestras have as many as

eight or ten players in the bass section (Pekar 11).

There were several solutions to the sonic problems presented during the 1930s.

Steel wrappings were added to gut strings and string heights were raised (thus

increasing string tension and resulting volume), and there were isolated, unsuc-

cessful attempts to amplify the acoustic bass. By the 1930s, Rickenbacker, Regal,

Vega, Gibson, and other instrument manufacturers were trying to develop acoustic

basses with electric amplification.

Bluegrass and commercial country music adopted the acoustic bass for both live

performances and recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. But basses were sometimes

too expensive for many hillbilly musicians and, instead, bass lines were often sup-

plied by the lower strings of the accompanying guitar or by single-stringed basses

constructed from washtubs, wire, and broomsticks. Although fine old antique

instruments were available for large sums of money in the 1950s for professional

musicians in orchestral professions, most basses of the rockabilly era were usually

of lesser quality. But the sound they produced, with little sustain or volume, and

limited overtones, added a certain cultural element to rockabilly recordings. In the

early 1950s, for example, the first bass Clayton Perkins played with his brother

Carl was a homemade two-string bass that weighed twice as much as a factory-

made model; it was the closest thing to a bass available to the inspired young

musicians (Perkins and McGee 46).

In bluegrass, country, and especially rockabilly, the acoustic bass supplied more

than simply the lower pitches in the ensemble. Rockabilly bassists used a slap-

ping technique in the right hand, which helped to punctuate the notes and

rhythms played. The slapping is perhaps better described as snapping the

string against the fingerboard so as to create a percussive effect on beats 1 and 3,

followed by a slapping of the strings with the palm of the hand on beats 2 and 4.

The bassist was responsible for both tonal and rhythmic elements. In some cases

dotted eighth and triplet subdivisions can be produced. But slapping the bass

requires the string to snap against the fingerboard, thus impeding its vibrations.

Plucking the string sideways in the more traditional method allows for more

vibration and low-end frequency resonance from the body of the instrument. So,

although the slapping technique does punctuate notes with high frequencies, it

ultimately squelches the lower frequencies of the note being produced. The differ-

ence in tone and clarity between these two techniques can be heard by comparing

Bill Blacks bass lines from his recordings with Elvis Presley at Sun to those of

Bob Moore on the recordings of Ric Carty in Nashville.

4

Where Black forfeited a

full, rich tone for the more dramatic slapping style, Moore generally used a more

traditional plucking style, allowing the bass to resonate.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

354 Brewer

Slapping the bass for percussive effect had been done long before the 1950s,

which is testament to the obviousness of the technique. A pioneer of the technique

was George Pops Foster in the 1930s, and it was perpetuated by John Lindsay,

Milt Hinton, Ray Brown, and others in the 1950s. Steve Brown tastefully employs

the technique in Jean Goldkettes recording of My Pretty Girl in 1927, and both

Ranson Knowling and Willie Dixon occasionally slapped the bass on some blues

recordings in the 1940s (Morrison 259). Slapping can often be heard during

solo sections of Hank Williamss recordings (Move It On Over, for example). The

technique was also performed to perfection by Marshall Lytle on the 1955 record-

ing of (Were Gonna) Rock Around the Clock, by Bill Haley and His Comets

(Shipton 302).

The slapping technique was often intensified in rockabilly by adding taped echo

effects during the recording process. This combination produced an overwhelming

and essential component of what is now often termed authentic rockabilly.

5

Carl

Perkins recounted his brother Claytons enthusiastic playing style to David McGee

in Go, Cat, Go:

The minute Clayton started that clickin behind Jays rhythm [guitar], then it all

exploded. It doesnt take a great musician to play. It takes feel, and a sound, and

thats what I heard. Im telling you theres times when us three boys sounded

like five people. That bass sounded like two instrumentsone clickin, and one

carrying that rhythm. (Perkins and McGee 47)

Perkins also recounts that he wanted his brother to click the strings in time rather

than focus on individual notes as the players on the Grand Ol Opry did. He

wanted the bass to imitate the sound of his foot tapping on the rickety front porch

of their shack in Tennessee (Perkins and McGee 46).

The electric bass guitar

Leo Fenders solid-bodied Precision Bass, which was available in the United

States by 1951, is now commonly referred to as the first electric bass guitar. But it

has recently been discovered that Paul H. Tutmarc had developed a solid-bodied

electric bass guitar in 1933 (Jasson and Malandrone 2022). It was capable of pro-

ducing more volume than several acoustic basses playing simultaneously. Simi-

larly, James Thompson built a solid-bodied electric guitar for recording purposes

in 1934. It was produced to fill the growing needs of bass players in smaller dance

bands who wanted more portability, volume, and left-hand harmonic precision

from their instruments. The relatively reasonable retail price must have played

a role in the popularity of the Precision Bass as well. By 1960, it had virtually

replaced the upright bass and had revolutionized the role of the bassist in ver-

nacular music. The relatively simple harmonic structures of early hillbilly compo-

sitions allowed the bassist (dressed in vaudevillian clown clothes, complete with

front tooth blacked out) to supply comic relief during performances. Certainly in

some way this stereotyped role was spurred on or at least enhanced by the mere

presence of the antique-looking and physically awkward acoustic bass.

Its no coincidence, then, that with the loss of the uprights visual reminder

of musical heritage, the bass players purpose in the ensemble and role on

stage changed as the electric bass became more commonly used. The compact

properties of the electric bass allowed the player new flexibility in the creative

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 355

and performance process. Instead of being limited to extra duties as a comic rube,

which were more visual than aural, the new volume and clarity of the electric bass

allowed bassists musical and physical freedoms (Malone 126, 204). Other proto-

type amplified basses were used as early as 1940 by jazz sidemen with the Lionel

Hampton band. Monk Montgomery, while playing with Hampton in 1953, for

example, is said to be the first jazz musician to have recorded the electric bass

guitar (Bacon and Ferguson 328). The relatively late addition of the electric bass to

jazz recordings may be, in part, due to the reinforcement of bass lines by the left

hand of the stride piano style.

In R&B, too, the electric bass found a home. Dave Myers, who switched from

guitar to the electric bass in 1958, helped make the Fender bass a success with his

recordings for Chicago blues artists. B. B. King, Little Walter, and Big Mama

Thornton all adopted the instrument for their groups to overcome the noise levels

found in nightclubs and road houses. In Detroit, James Jamerson switched to the

electric bass and played most of the bass lines recorded for the Motown label from

1959 to 1972 (Goldsby 30).

Because of its similarity to the guitar, played horizontally rather than vertically,

many of the first electric bassists were converted guitarists familiar with fretted

fingerboards and the technique associated with using a pick. Indeed, Leo Fender

invited the advice of professional guitarists and bassists from country, western

swing, and jazz while developing his prototype Precision Bass in 1951. If an

upright player was not accustomed to playing a fretted instrument, the electric

bass guitar required all new techniques for the converting player. All four of the

fingers on the left hand could be used with more ease and the right hand could

produce the sound by either the use of a plectrum or fingertips. Minuscule pitch

adjustments in the left hand were no longer necessary as much as precise finger

placement between the frets. Therefore, where the player once relied on helpful

portamento between position shifts, he now had to land precisely on the note. The

difference between acoustic and amplified instruments is explained by Muddy

Waters: That loud sound would tell everything you were doing. On acoustic, you

could mess up a lot of stuff and no one would know that youd ever missed

(Waksman 124).

Like the electric guitar, the new amplification of the bass also made new

demands on the player. For example, Bill Black, bassist for Elvis Presley, decided to

switch from his upright bass to electric some months prior to the recording of the

soundtrack for Jailhouse Rock in 1957. The switch to the fretted neck proved to be

difficult and frustrating for Black, who had no experience with guitar techniques

and was infamous for his microtonal idiosyncrasies on the upright. During the

recording of (Youre So Square) Baby I Dont Care, he threw the new electric

instrument across the studio floor in disgust after his repeated attempts to record

the introduction (Guralnick Last 408). He did, however, continue to play the instru-

ment during his successful recordings with the Bill Black Combo in the late 1950s

and early 1960s (Guralnick Good 9091).

Joe B. Mauldin played acoustic bass on all of the hit recordings by Buddy Holly,

but converted to a Fender electric bass during the summer of 1958 for what would

become Buddy Hollys last tour (Goldrosen and Beecher 119). He apparently had

no trouble making the switch and became more animated on stage. Bobby Jones,

who played on the road with Gene Vincent in the late 1950s, first took an interest

in the guitar when he was about thirteen years old and began playing the bass

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

356 Brewer

guitar some time around 1956. Unlike Jack Neal, his accomplished predecessor in

the Blue Caps, Jones never even played the acoustic bass. While on a world tour

with Gene Vincent, Jones mainly played a Fender bass.

6

The rockabilly perspective

As the musicians in the following section of this study will demonstrate, the

arrival of the electric bass guitar provided answers to many of the plights faced by

acoustic bassists.

7

In retrospect, these musicians have mixed feelings about the

electric bass and its role in the development of popular music, but most agree that

the portability of the electric bass was of utmost importance. To a lesser degree they

insinuate that its sound was more controllable and predictable, with intonation

no longer being problematic because of the fretted neck. There is agreement that

the volume of the electric bass provided a certain sonic power to the ensemble.

Most important for recording purposes, the instrument produced an undeviating

volume level, which made it easier to record and to hear in live concert settings

(Johnson 177).

Keeping in mind these changes caused by the advent of the electric bass in

other vernacular styles of music, most of which provided source material for the

rockabilly movement, what role did the electric bass guitar play in the transfor-

mation from 1950s rockabilly to what Craig Morrison terms white rock of the

1960s? As far as helping in the explanation of rockabilly as a distinct style and

despite my own convictions, the following quotations generally avoid commitment

to the idea that the electric bass played a role in the demise of rockabilly as a

distinct style.

Ken Davis, a guitarist and electric bassist active in the mid and late 1950s,

recalls the era of the appearance of the electric bass guitar:

I started playing electric bass in 1956. I took lessons from a Milwaukee teacher

who told me to keep it simple and to play it as a rhythm instrument. The main

reason was to allow me a better chance of getting in a band. I liked it . . . it was

great. To me, the electric bass, if played right, was a definite improvement to the

bands overall sound. By played right, I mean to play it as a bass and not like

a guitar as so many guitar-pickers-turned-to-bass-players had a tendency to do.

8

Davis is one of the few interviewed for this study who insinuate that there was a

prestige factor involved in owning an electric bass guitar and that it enabled him

to be hired by a band. There were certainly similar inclinations in R&B groups

during that period, who used amplification as a means to remain competitive in

the louder performance venues (Waksman 122).

Rockabilly musician Bob Kelly has similar memories:

Its funny you should mention the electric bass mainly because I am sort of in

the legends stage of my life and lots of rockabillies come up to me and ask

about the music of the 1950s. I got a Fender electric bass and amp as soon as

they were available and we could afford to buy one. Most of us back then were

guitar players that learned to play bass because we didnt need four guitar play-

ers in a band. The first one I saw was at a recording session at Sellers Recording

Studio in Fort Worth, Texas. I think that was about 1956 or 57. I bought my first

Fender Precision Bass in late 1958 or early 1959. I still played guitar in my own

band but I played bass with Scotty McKays band. As soon as the Fender Jazz

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 357

Bass came out, I immediately bought one because they were so much easier for

a guitar player to play.

Some of the really hot rhythm and blues records were beginning to use the

electric bass and, being a true rocker, I thought that was the only way to go. So,

I never played standup bass again. Some of the rockabilly guys today really

dont know how much bigger it made the band sound when you had an electric

bass. It was like a wimpy band becoming a killer. When the Fender company

started making the Precision Bass in the middle 1950s, thats when it all started to

explode and made it possible for rock and roll to emerge. It was a combination

of the electric guitar and the Fender electric bass that made it possible to have

rock and roll. The young kids can play the upright bass now because the

electronics are good enough to compete with the electric guitars and such.

9

These statements seem to suggest that the amplified electric bass supplied a

certain power and fullness that was, in part, responsible for the formation of rock

and roll after the rockabilly period. Bob Kellys comments insinuate that rock and

roll, as a style, should be partly defined as an ensemble sound with all electrified

instruments. Since many of the first generation of electric bassists were converted

electric guitarists, these quotations imply that the new capabilities inherent in the

electric bass challenged the traditional role of the instrument in the ensemble.

Where the physical limitations of the upright had prescribed the notes played for

the musical arrangement, the electric bass opened new doors.

10

Bill Mack, who played electric bass with Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps,

remembers the appearance of the electric bass guitar and its idiosyncrasies:

I started playing upright bass in 1947. I switched to electric in 1956 because it was

easier and it took up less room when going to a gig. The first time I saw an

electric bass was in the middle 1950s. I played one in a club in Piner, Kentucky,

called The Chicken Roost. It was a Gibson or a Kay and I really fell in love with

it. It was as different as night and day. The slap bass subsided somewhat after I

played some shows with Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, and Carl Perkins. Going

from one note to another just got easier and easier the more I played it. I had to

learn the frets but it didnt take long. For me, it was much easier than upright. It

allowed the player to play differently. The action [string height] became much

faster and easier to play. After a few weeks on the road with my electric bass all

the bands started using the electric bass everywhere I went.

The electric [bass] affected the way drums were played because it added

punch to the music and allowed the drummer to start adding rolls and riffs.

11

Mack recalls his early years, around 1955, with the electric bass and the

informality of instrumentation and personnel:

Paul [Peek] knew a musician from Greenville, named Red Redding, who had

moved to the Washington D.C. area. Paul asked him if I could come and play

bass in the band also. Red Redding said yes, bring him on. Red Redding was

gonna play his upright bass in the band, but when I got there, Red switched

from the upright bass to rhythm guitar, and I got to play my electric bass in The

Tunetoppers band. I had just changed over to the Fender electric bass. To my

knowledge I was the only one out there with an electric bass, especially on the

shows that I played. Marshall Grant asked me if the electric bass was hard to

play. I told him that I thought that it was easy. Later when we played a show

with Johnny Cash, Marshall Grant was playing an electric bass.

12

Dickie Harrell, who was the drummer for Gene Vincents Blue Caps during its

developmental years and is now one of the great mentors in the rockabilly revival,

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

358 Brewer

also has great respect for the electric bass. Yet his comments reveal the irony of the

displacement of the acoustic bass:

At first the standup bass was it! Then it changed to the electric. The electric has

more drive and adds a lot to the music. But with the upright you did a lot of

slapping. Gene [Vincent] used electric bass and his whole sound changed. Lotta

Lovin was a completely different sound. The electric adds so much to the music

and its easier for the player also.

13

The later 1950s recordings by Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps do, indeed, push

the limits of rockabilly by their increased tempi and exemplify the new pace of later

rockabilly music. The electric bass lines, which are rooted in traditional walking

eighth-note boogie-woogie patterns, stray into chromatic movement because of the

quick tempo. On the other hand, at these faster tempi, an acoustic bass player

would have probably shifted to a two-beat pattern, leaving the electric guitar to

play the faster boogie lines. Dickie Harrells dramatic snare-drum fills and other

sassy rhythmic accents, for which he has become famous, were made possible

because of the underlying rhythmic security supplied by the electric bass.

These subtle changes in performance were noticed by the Rolling Stones

guitarist, Keith Richards, who was influenced by the later rockabilly tours in

England:

The thing that really intrigued me, that turned me on to playing, was the rhyth-

mic ambiguity . . . the suggested rhythms going on, or a certain tension. Espe-

cially in early rock and roll, theres a tension between the 4/4 beat and the

eighths going on with the guitars. That was probably because the rhythm sec-

tion was still playing pretty much like a swing band. There was still a regular jazz

beat, 4/4 to the bar, a swing/shuffle.

It suddenly changed in 58, 59, 60, until it was all over by the early 60s. The

drummers were starting to play eight to the bar, and I thought at first maybe

they were just going for more power. Then I realized that, no, it was because of

the bass. The advent of reliable electric bass guitar. The traditional double bass

went bye-bye. This thing thats taller than most guys that play the thing. The

guitar players were being relegated to bass. If you didnt even have a bass, you

could tune down a guitar and play four strings; once you had an actual bass, it

was much louder than an acoustic pumping eight to the bar. And the natural

inclination of the drummer is then to pick up on what the new bass is doing,

because thats what youve got to follow. (Wheeler 97)

Although the rhythmic feel remained in the swing pattern, the late 1950s record-

ings by the Blue Caps and the statements above by two of its members and audi-

ence suggest that the acoustic bass simply could not keep up with the demands of

the transitional period in pop music.

14

The electric bass could be viewed as both

the cause and effect of the high level of intensity in these recordings. This is the

rockabilly style and instrumentation that the 1960s generation of British musicians

was hearing performed in American rockabilly tours in the late 1950s and early

1960s.

Bobby Wayne defends the qualities of the antique upright sound, but also

acknowledges the practicality of the electric bass:

I bought a used Kay upright bass in the 1950s for $35. I played slap bass until

the late 1960s. The first one I saw was in the 1950s. I didnt like it for my country

and rockabilly music because the electric bass was too loud! Besides, we couldnt

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 359

afford an electric bass. I didnt like it much because most of the guys tried to play

it like a guitar. Little pop and jazz combos used them and they sounded okay

with that sort of music. But the electric bass was more efficient than the dog-

house bass and easier to transport to gigs. The electric bass took over because so

many different things can be done with it. I always used to say, why dig a ditch

with a teaspoon when you can use a backhoe? You know the volume of the

doghouse was perfect even without a pickup. The doghouse was more felt than

heard!

15

The overall volume level of authentic rockabilly (at least in an ensemble of

steel string guitar, electric guitar, and acoustic bass) must have been pretty well

balanced and similar to that of bluegrass bands. For example, the acoustic guitar,

being strummed by the lead vocalist, is audible in the earliest recordings of

rockabilly and was commonly picked up by the vocal microphone. The volume

level of this style of rockabilly was dictated by the sonic properties of the acoustic

instruments. To this extent, an argument could be made that rockabilly was ill-

suited to larger stages and venues and better suited to honkytonks and private

parties. Judging by its instrumentation, rockabilly, originally, was the informal

and spontaneous chamber music of the displaced rural population living in an

urban environment.

Jimmy Harrell of the act called Jimmy and Alton reminisces on his economic

level during his formative years:

I learned to play the washtub bass at home prior to enlisting in the Navy. When

we decided to form a little group in San Diego we knew that we couldnt afford

a real one so we went to the store and bought a washtub, a broomstick, and

some cord and in no time we were in business. Later on, we made enough

money to rent an upright at Smokey Rogers [Ferlin Huskeys father-in-law]

music store in El Cajon. So in those days, it was purely economic reasons that

we started with the washtub then went to upright. It still amazes me how good

that old tub bass sounded, particularly with the type of music we were playing

country and roots-rock now called rockabilly. When we formed Jimmy and

Gene and the Rhythm Kings, the bass player just happened to own an upright.

16

Regardless of its cultural roots or performance purpose, the changing styles

of American popular music are seldom dictated by societal norms or performers

economic restrictions. Rockabilly performers reflections on the past attest to the

constantly changing commercial environment in which popular music exists.

J. M. Van Eaton, a Sun Studio session musician, remembers the appearance of

the electric bass and its effects on the music Sun Studio created:

Rockabilly had a lot of the slap bass in it and along about that same time people

were changing over from the upright bass to electric bass and that made a

difference in the sound. (Morrison 8)

Another session player at Sun, Roland Janes, who is openly skeptical of the value

of academic research in rockabilly, became animated and outspoken when I raised

the theory that the electric bass helped dilute the rockabilly style. He said: I know

you guys like to think we were living in a case . . . see, musicians evolve, man. We

evolved just like the instruments.

17

His practical and utilitarian philosophy

toward music explains how the electric bass must have been viewed by many:

I liked it [the electric bass]. . . . It gave a certain fullness. . . . [W]ith the acoustic, the

low end wasnt there. The electric just had a different tone. The acoustic bass was

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

360 Brewer

hard to record too . . . depending on the player. I used to put a mike on the

f hole and one about five inches over the bridge. Its easy to record when you

have a good player, but most of them used to just beat on it and slap around

on it. The electric was easier. The old bass was hard to get around. You had to

worry about it staying in tune. They were hard to maintain too.

18

Although Janes threw my proposal aside, he did volunteer that the music he

played and recorded during the 19571960 period was not really rockabilly. He

considered the sessions he played for Jerry Lee Lewis and Billy Lee Riley, for

example, to be more rock. His guarded and subtle definition does support the

theory that rockabilly was a transitional genre during the development of rock and

roll. Coincidentally, Norman Petty, producer for Buddy Holly, also placed a small

microphone between the strings at the top of the acoustic bass to capture the per-

cussive effect, and other microphones were positioned around the instrument to

hear actual pitches (Goldrosen and Beecher 61). Likewise, Paul Burlison, guitarist

for Johnny Burnette and the Rock and Roll Trio, recalled that the engineers at his

1956 sessions in Nashville for Coral Records positioned a microphone approxi-

mately one-and-a-half feet from the top of the fingerboard above Dorsey Burnettes

left hand.

19

As mentioned earlier, the electric bass reduced the physical demands on its

converted player. Rockabilly bassists played with such vigor that the acoustic

bass strings would cause damage to their instruments, and the repetitive grabbing

and slapping of the instrument took its toll on their fingertips as well. Marshall

Lytle, bassist for Bill Haley and His Comets, remembers his induction into popular

music:

Bill [Haley] asked me to come and play the bass for him. I said that I didnt know

how to play a bass. He said Ill teach you. So he spent one hour and taught me

the basic chords plus how to slap back and get a shuffle beat. The day I joined

The Saddlemen, I bought a bass.

20

He also remembers that his fingers were so sore and bloody that he had to

wrap tape around them to pound the strings of his bass fiddle. Later, when thick

calluses formed on his hands, the band-aids were no longer necessary.

21

Paul

Burlison also remembers the effects of the instrument on Dorsey Burnette:

Dorsey would slap the stew out of that thing. Ive seen him slap that thing till

the blood was running out of his fingers. Hed put tape on them, and when hed

pull the tape off, hed pull off a layer of skin. Now, a lot of people use power

and stuff [electric amplifications], But Ive seen Dorsey slap that thing. Id feel

so sorry for him. And he didnt do it like Bill and Johnny [the Black Brothers].

He [Dorsey] would bow-and-arrow that thing. Bill [Black] would take that

E-string, the big string, and hed loosen it about half way. He didnt even tune it.

He would hit it first then pull. He was slapping that string with the palm of his

hand. But Dorsey would pull them out and let them slap back against the neck.

Dorsey did it the hard way. By pulling it out and letting it slap against the neck.

(Bowman and Johnson 21)

Burlison further recounts similar logistical problems with the acoustic bass while

touring with the Rock and Roll Trio: One time Dorseys bridge busted. Dorsey

pulled the strings so hard, it came off right in the middle of a song. Sometimes

the G-strings would get unraveled. He did break one or two (Bowman and

Johnson 21).

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 361

I had a long conversation with Burlison during the Memphis Music and

Heritage Festival in 1998 about the importance of the upright bass to an authentic

rockabilly sound; he agreed that the slapping technique was essential. But he also

stated that the young players, often from Europe, were almost too good and had

developed the slapping technique into an art form.

Roy Huskey Jr., a current Nashville session bass player, describes the technique:

For rockabilly slap, I use three fingers to pull the string. For bluegrass slapping,

Ill use only one finger: I usually pop or pull the string and then come back and

slap the board. You have to do it a lot for your hands to get used to it. Ill use gut

[strings] for slapping, but Ive also used metal strings. If the engineer is getting a

good sound on the bass, it can be a lot of fun to slap on metal strings. They have

a more raucous sound, and you get a lot more overtones. I show up with a

gut-string bass for most recordings.

22

Regardless of the qualms the performers themselves had with the acoustic bass,

there had been many enormously successful recordings in the rockabilly period

that exploited its unique properties. The electric bass had yet to prove itself in

the studio. As Marshall Lytle, who performed with Bill Haley and His Comets,

explains the control the recording studios had over instrumentation: I switched

to Fender bass for our stage work in 1955 but continued with the upright for

recordings because of the clicking shuffle beat I created. [Thats] what the record

company wanted.

23

Jerry Lee Merritt, who played a Fender Stratocaster electric guitar with Gene

Vincents band for a very successful tour of Japan in 1959, recalls: The first

bass guitar I ever saw was a Dan Electro and it was a six-string bass. But when

I recorded with Gene Vincent for Capitol in Hollywood, California, we used an

upright bass.

24

These statements imply that, regardless of the practical lessons the musicians

had experienced on extended road tours, the record companies were still looking

for the acoustic bass sounds to which they had grown accustomed.

Carl Perkins explains the techniques used by his brother Clayton:

Clayton attacked that bass; he had something to prove and he proved it. His

attitude was Wait a minute, Im part of this! Im a big part of this and Im gonna

ride it to the hilt! Im the best damn bass slapper to ever come out of these parts,

and Im gonna make the girls look at me. And that was one of the reasons he

pushed that bass so hard and hit it hard. He blistered his hand but never backed

off of it. (Perkins and McGee 47)

In the early years of performing, Clayton Perkins learned the importance of

clowning while playing his upright. His antics included balancing on the

basss side with no hands and with the aid of a rubber ball on the endpin, riding

the bass pogostick-style into the audience (Perkins and McGee 66). It is odd that

Carl Perkins speaks so highly of the upright bass. In the 1960s and 1970s, his band

used the electric bass exclusively. His son did, however, play the upright with him

from time to time in the 1980s.

Jody Reynolds, who has enjoyed a second career in the rockabilly revival, also

seems to have preferred the upright bass:

I first saw an electric bass in 1956. It was okay. Im a guitar player, not really a

bass player. The electric made players play too loud and too much. Everyone

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

362 Brewer

played louder. I missed the slapping of the upright. There was a single slap, a

double slap, and a triple slap.

25

Jimmy Harrell reiterates the downfalls of the acoustic bass in the later 1950s:

Basically, I believe that there are two reasons most everyone switched to the

electric bass. Number one was transportability. It was awfully hard to haul that

thing [n upright bass] around. And second, all the engineers that I knew said that

it was much easier to record an electric than an upright (although Sam Phillips

certainly didnt seem to have a problem getting a good sound out of Bill Blacks

bass).

The rockabilly sound is much better with an upright and Im glad to see

modern groups using it. But by no means do I think that an electric bass ruins

rockabilly.

26

Harrells reluctance to condemn the electric bass and his overall acceptance of

it into rockabilly demonstrate the difficulties found in all definitions of musical

genre. Perhaps he was simply too close to the creation of rock and roll to form

negative opinions. Others, who found notoriety in the rockabilly revival, have

reconsidered the instrumentation of the ensemble.

27

Conclusions

There is little doubt that the displacement of the upright bass played a role in the

stylistic changes of blues, rock, and R&B. We can only speculate what direction

popular music would have taken if the electric bass had been introduced during

an era of less social and musical turmoil. As the record-buying market was shifting

from the musical tastes of Eisenhower America, leaving the postwar era, and enter-

ing the era of the space race, the electric bass guitar quickly found great acceptance

in popular and vernacular musics. The effects of the new technology were wide-

ranging and blind to racial barriers. Not only was there impact on white vernacu-

lar music, but the electric bass guitar also played a role in solidifying R&B as a

genre. It is not merely coincidence that the electric bass was deliberately shunned

by those performers of bluegrass who appreciated the authentic qualities of the

upright bass and the tradition it represented.

The information from the musicians interviewed for this study remains incon-

clusive as to the importance of the electric bass and its role in the development of

popular music. There is some consensus that the portability of the electric bass

was of utmost importance to the everyday life of a traveling musician in the 1950s.

The acoustic bass was cumbersome and prone to being damaged while in transit.

There seems to be agreement that the electric bass increased the overall sonic

volume of the rock and roll ensemble and that it allowed the player to perform

more complicated lines at faster tempi with ease. To a lesser degree, the musicians

maintain that the sound of the electric bass guitar was more controllable and

predictable, both in live and recording situations. But there is complete agreement

among my interviewees that the volume of the electric bass provided a certain

sonic power to the ensemble, which was important to rock and roll.

Most important to the definition of rockabilly, my sources generally avoid com-

mitment to my theory that the electric bass played a role in the demise of rockabilly

as a distinct style. In the rockabilly ensemble, the acoustic bass was a remnant

from hillbilly, bluegrass, and other white vernacular musical styles before 1954.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 363

Although several interviewees gave testament to the importance of the uprights

slapping technique to the rockabilly sound, most were, nevertheless, grateful for

the invention of the electric bass guitar.

The displacement of the upright bass from vernacular music in the United States

did not occur in a vacuum. By the mid 1950s, as the drum set snuck its way into

rockabilly and eventually country performance settings, both live and on record-

ings, the beating of the hi-hat cymbals in swing patterns and eighth-note subdivi-

sions replaced the sound formerly supplied in rockabilly by the slap technique

and tape echo.

28

This percussive sonic expansion, combined with the advent of the

electrically amplified bass guitar, provided a new and more constant rhythmic and

harmonic grounding, which allowed treble instruments more rhythmic freedoms.

But with the addition of the drum set and electric bass guitar to rock music of the

late 1950s, the frenetic slapping technique and the sometimes nebulous tonality

and haphazard intervallic patterns identified with the rockabilly upright bass

style were eliminated. However, the acoustic bass remained the standard for main-

stream pop records where studio orchestras were hired to support vocalists.

Nashville musician Bob Moore, for example, played acoustic bass on nearly all of

the 1960s RCA recordings for Elvis Presley. He did, however, decide to use an

electric bass on Down in the Alley, recorded in 1966 (Guralnick Careless 232).

Even the recordings being produced in the last years of the 1950s at rockabillys

birthplace, Sun Studio, followed the popular trends in music by discarding swing

rhythmic patterns and slapping bass effects, and adopting arrangements with

straight eighth-note subdivisions.

29

After examining the memories of the musicians of the rockabilly movement, it

is also obvious and somewhat surprising that the musicians who created the

rockabilly style were generally oblivious to their role in the evolution of popular

music; this explains their open-minded acceptance of the electric bass. It is ironic

that their preference of the electric bass eliminated an important element of

the genre they createdrockabilly. With the appearance of the electric bass,

rockabilly no longer had a representative instrument of yesteryear to mock. The

frenetic energy supplied by irreverent performance techniques that exploited the

instruments limitations was lost. This standardizing of instrumentation in rock-

oriented popular music refocused the listener toward the singer and his song and

set the stage for the teen idols who would inherit the nations new youth market,

which mushroomed during the waning years of rockabilly. Now, only in retro-

spect, which is often clouded by their recent successes in the rockabilly revival, do

these pioneers of popular music reconsider the value of the acoustic bass to the

rockabilly style.

Notes

1. Rockabilly is defined as an early style of white rock and roll that blended blues with

country music. The experimental period of rockabilly was relatively short-lived, last-

ing roughly from 1954 to 1960. Although there were some rockabilly releases toward

the end of the 1950s, mostly promoted by small independent record labels with

limited marketing, by the end of the 1950s rockabilly vocalists and instrumentalists

had been integrated into other styles of popular music.

2. In some cases there was no electric guitar used for solos on rockabilly recordings.

Such is the case with Ric Carteys 1956 demos for RCA, in which producer Jerry Reed

played solos on an acoustic steel-stringed guitar.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

364 Brewer

3. The 1970s saw a number of historical and sociological publications pertaining to

rockabilly, and in recent years a number of insightful biographies have been written

about the leading performers and instrumental sidemen of the era. Other aspects

of rockabilly, especially obscure and unreleased recordings and related biographical

information, have now developed an almost cultlike following with innumerable

websites and magazines devoted to the subject, and a large number of rockabilly acts

touring all over the world. In my own research into the music of the rockabilly

period, I have published the article The Use of Habanera Rhythm in Rockabilly

Music (Brewer) which examines rhythm interpretation and execution by

rockabilly musicians. This current study is a logical continuation of that research.

4. See Get Hot or Go Home: Vintage RCA Rockabilly 5659. LP. Country Music Foundation

Records CMF-014-L, 1988.

5. This slapping technique has been developed to an extreme art by bassists of the

rockabilly revival. See <http://members.aol.com/rodcat/bassindex.html> or <http://

www.spinne.vnweb.com/Slap.htm> for more information.

6. Website for Bobby Jones posted by the Rockabilly Hall of Fame <http://my.athenet.net/

~genevinc/gvbobbyjones.html>.

7. I mailed a two-page questionnaire to some thirty musicians (to which I received ten

written responses) and had e-mail and telephone correspondence with many others.

Other supporting quotations have been cited from other published sources.

8. Quotations from written responses to my questionnaire by Ken Davis, March 2000.

Ken Davis learned to sing and accompany himself on guitar/electric bass shortly after

his 1954 graduation from high school in Racine, Wisconsin. In early 1958, he and the

Honeybees, along with the Country Gentlemen, recorded Bundle of Lovin and

Sittin Pretty at the Pfau recording studio in Milwaukee. The record was released on

the Pfau label in March 1958 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/KenDavis.html>.

9. Quotations from responses by Bob Kelly to my e-mailed questionnaire, March 15,

2000. Gene Vincent recorded Kellys Git It and Somebody Help Me. Kelly was the

son of musicians in the small West Texas town of Olney. He began playing the guitar

at ten years old and was writing songs and singing them at thirteen. See <http://

my.athenet.net/~genevinc/BobGIKelly.html>.

10. The style in which the electric bass is played on WalkDont Run (1960) by the

Ventures is a good example of the new flexibility of the electric bass guitar.

11. Quotations from written responses to my questionnaire by Bill Mack, March 27, 2000.

Born William E. McCreight in Greenville, South Carolina, March 19, 1933, Mack was

the second bass player for Gene Vincent and The Blue Caps and toured from March

through December of 1957 playing electric bass guitar.

12. Quotations from the Bill Mack website hosted by the Rockabilly Hall of Fame <http://

my.athenet.net/~genevinc/gvBillMack.html>.

13. Quotations from written responses to my questionnaire by Dickie Harrell, March

2000 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/gvdickie.html>.

14. The charting recordings by VincentBe-Bop-A-Lula (1956), Lotta Lovin (1957),

and Dance to the Bop (1958)were already several steps away from the hillbilly

roots of rockabilly. Vincents career began as a direct influence of Elvis Presleys

infectious style and his band was from a bluegrass and jazz background.

15. Quotations from written responses to my questionnaire by Bobby Wayne, March 24,

2000 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/BobbyWayne.html>.

16. Quotations from written reponses to my questionnaire by Jimmy Harrell, March 26,

2000.

17. Roland Janes, telephone interview, March 1, 2000.

18. Quotations from telephone interview with Roland Janes, March 1, 2000. Janes was a

staff guitarist at Sun Studio from the mid 1950s through the 1960s. He played on

records by Jerry Lee Lewis, Warren Smith, and Billy Lee Riley, to name a few.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 365

19. Information from a conversation with Paul Burlison during the Memphis Music and

Heritage Festival, 1998 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/pBurlison.html>.

20. Denise Rosier at www.basslicks.com.

21. Website for Bill Haley and the Comets. <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/

BillHaley.html>

22. Denise Rosier at www.basslicks.com.

23. Quotation from e-mail correspondence with Marshall Lytle, July 3, 2000.

24. Quotations from responses by Jerry Lee Merritt to my e-mailed questionnaire,

February 25, 2000 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/gvdickie.html>.

25. Quotations from written responses to my questionnaire by Jody Reynolds, March 12,

2000 <http://my.athenet.net/~genevinc/JodyReynolds.html>.

26. Quotations from responses to my e-mailed questionnaire by Jimmy Harrell, March

26, 2000. After leaving the Navy, Jimmy moved in with Alton (and his parents). Alton

and Jimmy recorded for Ace Record Company in Jackson, Mississippi. They cut two

songs for Ace entitled Looking for Someone and Got It Made in the Shade in 1958

at the Cosimo Recording Studio, New Orleans, Louisiana. They recorded Have Faith

in My Love and No More Crying the Blues at Sun Records on April 5, 1959. These

songs were released later on Sun 323. Exactly two months later, on June 5, 1959, Alton

and Jimmy recorded I Just Dont Know, Whats the Use, Why Do I Love You,

and The Longest Walk. All songs were subsequently reissued on vinyl LP and

CD. The Longest Walk cannot be located among the Sun masters. See<http://

my.athenet.net/~genevinc/AltonJimmy.html>.

27. Such is the case of Charlie Feathers, who spent a great deal of time checking and

double-checking the amplification and delay effects on the acoustic bass before his

performances in the 1980s.

28. Some good examples of rockabilly with drums and no bass-slapping technique are

Rock and Roll Ruby by Warren Smith (1956) and Red Hot by Billy Lee Riley

(1957). On That Aint Nothin But Right by Joey Castle (1958), the hi-hats supply

eighth-note subdivisions very similar to those caused by tape-delay echo.

29. On the two most popular records by Jerry Lee Lewis at Sun, Whole Lot of Shakin

Going On and Great Balls of Fire, there was no bass used.

Works cited

Bacon, Tony, and Jim Ferguson. Electric Bass Guitar. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz.

Ed. Barry Kernfeld. London: Macmillan, 1988. 328329.

Bowman, Robert, and Ross Johnson. The Train Started Rollin: A Conversation with Paul

Burlison of the Rock n Roll Trio. Journal of Country Music 11 (198687): 1725.

Brewer, Roy. The Use of Habanera Rhythm in Rockabilly Music. American Music 17

(1999): 30017.

Clevinger, Martin. The Evolution of the Electric Bass Guitar. www.batnet.com, 1987.

Goldrosen, John, and John Beecher. Remembering Buddy: The Definitive Biography of Buddy

Holly. New York: Penguin, 1986.

Goldsby, John. 100 and Counting: The Players Who Shaped 20th Century Bass. Bass

Player Jan. 2000: 2841.

Guralnick, Peter. Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Boston, MA: Back Bay, 1999.

. Good Rockin Tonight: Sun Records and the Birth of Rock n Roll. New York: St. Martins

Press, 1991.

. Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1994.

Jasson, Mikael, and Scott Malandrone. Jurassic Basses: Was There Electric Bass Before

Leo? Bass Player July 1997: 2022.

Johnson, Alphonso. Bass Guitar. The Guitar A Guide for Students and Teachers. Ed.

Michael Stimpson. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1990. 177190.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music U.S.A.: A Fifty-Year History. Austin: U of Texas P, 1968.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

366 Brewer

Morrison, Craig. Go Cat Go: Rockabilly Music and Its Makers. Urbana, IL: U of Illinois P,

1996.

Pekar, Harvey. Sopisticated Basses: The Pioneering Parts and Players of Duke Ellingtons

Golden Years. Bass Player Jan. 2000: 1127.

Perkins, Carl, and David McGee. Go, Cat, Go: The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, the King of

Rockabilly. New York: Hyperion, 1996.

Shipton, Alyn. Double Bass. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Ed. Barry Kernfeld.

London: Macmillan, 1988. 30103.

Waksman, Steve. Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical

Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999.

Wheeler, Tom. Keith Richards: Not Fade Away. Guitar Player 23 (1989): 92106.

Interviews and conversations

Burlison, Paul. Information from a personal conversation during the Memphis Music and

Heritage Festival, 1998.

Davis, Ken. Written responses to questionnaire, March 2000.

Harrell, Dickie. Written responses to questionnaire, March 2000.

Harrell, Jimmy. Written responses to questionnaire, March 26, 2000.

Janes, Roland. Quotations from telephone interview, March 1, 2000.

Kelly, Bob. Written responses to questionnaire, March 15, 2000.

Mack, Bill. Written responses to questionnaire, March 27, 2000.

Lytle, Marshall. Quotations from his answers to e-mail questionnaire July 3, 2000.

Merritt, Jerry Lee. Written responses to questionnaire, February 25, 2000.

Wayne, Bobby. Written responses to questionnaire, March 24, 2000.

Reynolds, Jody. Written responses to questionnaire, March 12, 2000.

Roy Brewer is currently a freelance musician and part-time lecturer at the University

of Oregon. He earned his PhD in musicology (regional studies) from the University of

Memphis in 1996.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

C

i

t

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

5

:

3

6

0

4

M

a

y

2

0

1

4

También podría gustarte

- Million Dollar Les Paul: In Search Of The Most Valuable Guitar In The WorldDe EverandMillion Dollar Les Paul: In Search Of The Most Valuable Guitar In The WorldCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Duke Robillard Biography For Release of His Band's New Album "Low Down and Tore Up"Documento2 páginasDuke Robillard Biography For Release of His Band's New Album "Low Down and Tore Up"Stony Plain RecordsAún no hay calificaciones

- Fender ElectricGuitars Manual (2011) EnglishDocumento36 páginasFender ElectricGuitars Manual (2011) Englishapellon7Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Rolling Stones - We Love You BassDocumento3 páginasThe Rolling Stones - We Love You BasssoteroAún no hay calificaciones

- Song List Guitar Tab White Pages - Volume 3 PDFDocumento6 páginasSong List Guitar Tab White Pages - Volume 3 PDFgarrotebill100% (1)

- The Tennessee StudDocumento1 páginaThe Tennessee StudChris SpenceAún no hay calificaciones

- BLUE SKY Tab - Allman Brothers Band - E-ChordsDocumento4 páginasBLUE SKY Tab - Allman Brothers Band - E-ChordsDany SatyogrohoAún no hay calificaciones

- Roy Clark's 12th Street Rag transcriptionDocumento18 páginasRoy Clark's 12th Street Rag transcriptionSteve RobertsAún no hay calificaciones

- Instruction Manual: - MaintenanceDocumento4 páginasInstruction Manual: - MaintenanceAzhar Ali ZafarAún no hay calificaciones

- Fender 1988Documento110 páginasFender 1988Hans VeraAún no hay calificaciones

- Want To Knock 'Em Dead in Nashville - Learn These 20 Tasty Country Licks - Guitar WorldDocumento6 páginasWant To Knock 'Em Dead in Nashville - Learn These 20 Tasty Country Licks - Guitar Worldμιχαλης καραγιαννηςAún no hay calificaciones

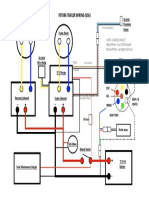

- Futura Trailers - Winch-Box-WiringDocumento1 páginaFutura Trailers - Winch-Box-Wiringsthollander100% (1)

- Más II-V-IDocumento15 páginasMás II-V-Igabriel4castellano100% (1)

- JMP-1H and JMP-1C: Owner'S ManualDocumento5 páginasJMP-1H and JMP-1C: Owner'S ManualmarcusolivusAún no hay calificaciones

- Operation Ivy - Bad Town BassDocumento2 páginasOperation Ivy - Bad Town BassToni AholaAún no hay calificaciones

- Gibson Les Paul Guitars HistoryDocumento15 páginasGibson Les Paul Guitars HistoryramjoceAún no hay calificaciones

- Heart-of-Gold - Neil-Young Punteos y AcordesDocumento11 páginasHeart-of-Gold - Neil-Young Punteos y AcordesximomateuAún no hay calificaciones

- Humbucker Pickup Models: Wiring Diagram For All Seymour DuncanDocumento2 páginasHumbucker Pickup Models: Wiring Diagram For All Seymour Duncanedgardo_alfaro8569Aún no hay calificaciones

- 12 ProgressionsDocumento2 páginas12 ProgressionsThomas CumberbatchAún no hay calificaciones

- ROVER TAB by Jethro Tull at Ultimate-GuitarDocumento4 páginasROVER TAB by Jethro Tull at Ultimate-GuitardermordAún no hay calificaciones

- Mana - Angel de Amor Bass PDFDocumento4 páginasMana - Angel de Amor Bass PDFToni AholaAún no hay calificaciones

- Guitar Guru: What Causes Buzzing Strings?Documento2 páginasGuitar Guru: What Causes Buzzing Strings?Jared WilliamsAún no hay calificaciones

- 5-Tone Tele Mod - Telecaster Guitar Forum PDFDocumento4 páginas5-Tone Tele Mod - Telecaster Guitar Forum PDFMasanobu TAKEMURAAún no hay calificaciones

- Acoustic Magazine Issue 47Documento2 páginasAcoustic Magazine Issue 47oysterhouseAún no hay calificaciones

- Sun Medley LeadsheetDocumento1 páginaSun Medley LeadsheetedinioAún no hay calificaciones

- TG 24 Crowded House - Don't Dream It's Over 1Documento1 páginaTG 24 Crowded House - Don't Dream It's Over 1ubaldo100% (1)

- 1mm1 Tab List v19Documento14 páginas1mm1 Tab List v19Liliana MadonnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Blues Bass Riff Lessons: Introduction to Repeated Bass LinesDocumento2 páginasBlues Bass Riff Lessons: Introduction to Repeated Bass LinesLeo FernándezAún no hay calificaciones

- Come OriginalDocumento4 páginasCome OriginalddssAún no hay calificaciones

- Guitar Buyer Magazine Issue 119Documento2 páginasGuitar Buyer Magazine Issue 119oysterhouse100% (1)

- Joe Walsh PDFDocumento2 páginasJoe Walsh PDFLugrinderAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Play Like Steve CropperDocumento8 páginasHow To Play Like Steve CropperChristopher ButsonAún no hay calificaciones

- GuitarsDocumento10 páginasGuitarsnonex2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mandolin Workshop With Herman Towles and Fiddle Workshop With Branson RainesDocumento1 páginaMandolin Workshop With Herman Towles and Fiddle Workshop With Branson RainesJennifer Brown BryanAún no hay calificaciones

- Fender Precision BassDocumento6 páginasFender Precision Bassloggynety159Aún no hay calificaciones

- 2004 Ibanez CatalogueDocumento22 páginas2004 Ibanez CatalogueAsad50% (2)

- Yamaha Guitar Serial Numbers - Dating Your Guitar - My Cool GuitarsDocumento7 páginasYamaha Guitar Serial Numbers - Dating Your Guitar - My Cool GuitarsMark GoducoAún no hay calificaciones

- 16 Series PDFDocumento8 páginas16 Series PDFfluidaimaginacionAún no hay calificaciones

- Duane Allman PDFDocumento1 páginaDuane Allman PDFLugrinderAún no hay calificaciones

- Jimi HendrixDocumento12 páginasJimi HendrixRiverAún no hay calificaciones

- Martin Price ListDocumento12 páginasMartin Price ListMeow Srivaranon100% (1)

- 2013 09 PDFDocumento131 páginas2013 09 PDFBcorgan100% (1)

- Guitarras Gibson 2Documento4 páginasGuitarras Gibson 2Oscar PenteadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Guns N Roses Appetite For Destructionpdf PDFDocumento96 páginasGuns N Roses Appetite For Destructionpdf PDFHeber Elias dos SantosAún no hay calificaciones

- Fuzz-Face-NPN-BC183L-Revision1 Devo Fare Questo Mannaggia CristttttDocumento1 páginaFuzz-Face-NPN-BC183L-Revision1 Devo Fare Questo Mannaggia CristttttMichele Paco Ardengo100% (1)

- h44 Stratotone e Size Plans v5Documento1 páginah44 Stratotone e Size Plans v5Jef CostelloAún no hay calificaciones

- HEY JOE TAB (Ver 8) by Jimi Hendrix at Ultimate-GuitarDocumento5 páginasHEY JOE TAB (Ver 8) by Jimi Hendrix at Ultimate-GuitardermordAún no hay calificaciones

- Judge Reed's Application For RehearingDocumento19 páginasJudge Reed's Application For RehearingEquality Case FilesAún no hay calificaciones

- Public Speaking: Harmonica: HistoryDocumento1 páginaPublic Speaking: Harmonica: HistoryLuis Alberto Gostín KrämerAún no hay calificaciones

- Fender Blacktop & Modern Player ElectricsDocumento5 páginasFender Blacktop & Modern Player ElectricsIgnacio Pérez-VictoriaAún no hay calificaciones

- All Web Site TunesDocumento28 páginasAll Web Site TunespseudoyouthAún no hay calificaciones

- MUSIC BOX BLUES CHORDS by Trans-Siberian Orchestra @Documento2 páginasMUSIC BOX BLUES CHORDS by Trans-Siberian Orchestra @watchman29Aún no hay calificaciones

- Scotty Moore Guitar LicksDocumento2 páginasScotty Moore Guitar Licksnotrock100% (1)

- Rickenbacker ManualDocumento8 páginasRickenbacker ManualKris CriadoAún no hay calificaciones

- California Dreamin'Documento2 páginasCalifornia Dreamin'Leentje Van ReynAún no hay calificaciones

- Bass Tab White PagesDocumento1018 páginasBass Tab White PagesAníbal AndradeAún no hay calificaciones

- First BluesDocumento3 páginasFirst BluesTakashiInadaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lowden Prices 2016Documento4 páginasLowden Prices 2016Dennis MurrayAún no hay calificaciones

- Guitar World - Vol.43 No. 08 August 2022-2Documento6 páginasGuitar World - Vol.43 No. 08 August 2022-2Benedito PradoAún no hay calificaciones

- Guitar Technique MethodDocumento41 páginasGuitar Technique MethodHans Marino100% (1)

- Electric Guitar Lesson PlanDocumento10 páginasElectric Guitar Lesson Planeric greenAún no hay calificaciones