Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Moving Toward Change 2010 Job Bank Survey

Cargado por

Mind Props0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

22 vistas11 páginasThis document summarizes the findings of a 2010 survey on the sociology job market. Key findings include:

1) There was a 32% increase in assistant and open faculty positions advertised in the ASA Job Bank from 2009 to 2010, indicating a recovery from declines in 2009, though total openings remain below historic averages.

2) The number of new PhDs declined 23% from 2008 to 2009, likely due to students delaying completion due to the poor job market.

3) 80% of advertised positions resulted in a new faculty hire, down slightly from 83% in 2009.

4) Over half (53.6%) of assistant/open position ads were by research and doctoral institutions

Descripción original:

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoThis document summarizes the findings of a 2010 survey on the sociology job market. Key findings include:

1) There was a 32% increase in assistant and open faculty positions advertised in the ASA Job Bank from 2009 to 2010, indicating a recovery from declines in 2009, though total openings remain below historic averages.

2) The number of new PhDs declined 23% from 2008 to 2009, likely due to students delaying completion due to the poor job market.

3) 80% of advertised positions resulted in a new faculty hire, down slightly from 83% in 2009.

4) Over half (53.6%) of assistant/open position ads were by research and doctoral institutions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

22 vistas11 páginasMoving Toward Change 2010 Job Bank Survey

Cargado por

Mind PropsThis document summarizes the findings of a 2010 survey on the sociology job market. Key findings include:

1) There was a 32% increase in assistant and open faculty positions advertised in the ASA Job Bank from 2009 to 2010, indicating a recovery from declines in 2009, though total openings remain below historic averages.

2) The number of new PhDs declined 23% from 2008 to 2009, likely due to students delaying completion due to the poor job market.

3) 80% of advertised positions resulted in a new faculty hire, down slightly from 83% in 2009.

4) Over half (53.6%) of assistant/open position ads were by research and doctoral institutions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 11

Roberta Spalter-Roth

American Sociological Association

Janene Scelza

American Sociological Association

Jerry Jacobs

University of Pennsylvania

Moving Toward Recovery:

Findings from the 2010 Job Bank Survey

Key Findings

Tere was a 32 percent

increase in assistant and

open rank faculty positions

advertised, a sharp

turnaround from declines

experienced in 2009;

Yet, total openings for these

types of positions remain

below historic averages and

did not fully recoup the

declines experienced during

2009;

Te number of new PhDs

declined sharply (23 percent)

between 2008 and 2009, most

likely because of students

delaying completion;

80 percent of advertised

positions yielded a new

faculty hire, down slightly

from the 83 percent observed

in 2009;

Just over half (53.6 percent)

of advertisements for

assistant and open rank

faculty positions were placed

by research and doctoral

institutions;

Tere are several notable

mismatches between the

felds of interest of graduate

students and the felds in

which departmental searches

are most common.

In 2009 we saw a dramatic decline

of 35 percent in the number of

assistant and open rank faculty

positions advertised in the American

Sociological Associations (ASA)

Job Bank, the major source of job

listings for the discipline (although

not all jobs available to sociologists

are listed). Likewise, there was a

dramatic 32 percent decline in the

number of departments advertising

these positions (Spalter-Roth,

Jacobs, and Scelza 2010).

By 2010, the job market in sociology

appears to have bottomed out and

a recovery seems to have begun.

The number of assistant and open

rank positions advertised in 2010

increased 32 percent, while the

number of advertising departments

increased 31 percent (see Figure

1). This growth is a cause for some

optimism among sociologists seeking

positions as assistant professors,

although the overhang of unplaced

or under-placed scholars will likely

continue to make the job market

challenging for newly-minted PhDs

for several years to come. Fewer

academic positions for new PhDs

were advertised last year (calendar

year 2009) than there were new

PhDs, with a ratio of 0.70 jobs per

new PhD. For calendar year 2010

there was about 1.2 jobs listed for

each sociologist receiving a PhD in

2009 (the last year for which data

is available). However, part of the

increase in jobs per person is the

result of a decline in the number of

new PhDs (which dropped from 477

in 2008 to 368 in 2009). This decline

of 23 percent most likely represents

a strategy of students delaying the

completion of their degree in hopes

of improvements in the job market. In

contrast to the increase in academic

jobs, there was a 16 percent decline

in the number of non-academic jobs.

The largest share of these positions

is post-doctoral fellowships, followed

by jobs in applied settings (see Table

1). The share of assistant professor

or open rank jobs advertised

by either stand-alone sociology

departments or joint sociology

departments remained constant at

about 62 percent, with the rest of the

advertisements for these positions

placed by departments outside of

sociology, not all of whom hired

sociologists.

The increase in the percentage

of academic positions advertised

in the ASA Job Bank occurred in

other humanities and social science

disciplines as well. However, the 35

percent increase in jobs for assistant

ASA Research Brief

August 2011

professors in sociology is higher than those reported

for two other disciplines for which specifc fgures are

available. The American Political Science Association

reported a 15 percent increase in advertisements for

assistant professors in its job listings (Jaschick 2011).

The American Historical Association reported a 21

percent increase in all positions over the same period

last year (Schmidt 2011) in contrast to the previous

year, which was described as the worst year ever.

This is the third survey of the job market done by

the ASA research department (see Too Many or Too

Few PhDs? Employment Opportunities in Academic

Sociology for fndings from the 2008 survey and

Still a Down Market: Findings From the 2009/2010

Job Bank Survey for fndings from the 2009 survey).

The intent of these surveys is to determine whether

departments that advertised academic jobs conducted

successful searches, whether those positions went

unflled and for what reason, and how searches varied

by institutional characteristics. This year for the frst

time we also matched the frequency of the specialty

areas for which departments sought applicants

and the frequency of specialty areas

chosen by student ASA members who

were perspective PhD candidates

with a masters degree. The coding

categories were based on areas of

special interest listed on the ASA

membership form.

We employed the previous years short

questionnaire and sent it to contacts

at each of the 338 departments or

schools that posted an advertisement

for at least one assistant professor

or open rank position in the ASA Job

Bank in calendar year 2010. Many of

these advertisements were for jobs that

began in the fall of 2011. The survey

was administered through Qualtrics,

which allows respondents to respond

online. We sent the survey to two

contact people in each department,

usually the chair and the person who

had placed the job advertisement.

We followed up with three reminders,

and then attempted to contact non-

responding departments via telephone. This year

the response rate was substantially lower than in the

previous year (71 percent compared to 91 percent),

with signifcant variation in response rates by type

of department and type of institution. This lower

response rate may be because we started the survey

later in the year when more department chairs my

have been on vacation. The tables presented in this

research brief limit counts and outcomes to those jobs

available in the United States.

Job Counts

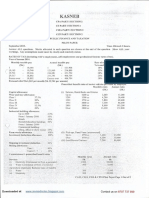

Table 1 shows the full count of jobs available in the

U.S. advertised in the ASA Job Bank in 2010. The

427 academic jobs that new PhDs could potentially fll

(including assistant, open rank and unspecifed rank)

constituted nearly 9 out of 10 of all faculty positions

advertised in the ASA Job Bank during 2010. The

assistant professor position is clearly the principal

portal for entry into academic careers. Assistant

professors may be more attractive to colleges and

universities because of their lower salaries and the

energy and focus they bring in anticipation of the

tenure-review process. It may also be the case that

some higher ranked faculty recruitment is not fully

Moving Toward Recovery: Findings from the 2010 Job Bank Survey 2

THE JOB MARKET SURVEY

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2009 and 2010.

1

Excludes foreign institutions.

Figure 1: Assistant & Open Rank Faculty Positions

Advertised, 2008 - 2010

1

2009 2010 2008

499

324

427

378

258

338

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Total Positions Advertised

Total Advertising

Departments

refected in the ASA advertisements because these

are not completely open searches. As noted above,

the number of academic jobs potentially available

to new PhDs increased by 32 percent compared

to those advertised in 2009. If we count non-U.S.

advertisements for assistant professors, open rank,

and unspecifed rank academic positions (including

those in Canada) there were an additional 44

positions advertised.

Almost all of an additional 212 non-academic jobs or

post-doctorates were likely available to new PhDs. If

these positions are added to the academic positions

then there would be about 1.7 jobs available for each

new PhD (Of course this does not count the number

of PhDs from prior years that did not fnd jobs that

matched their interests, those who took one-year

positions the year prior, or who completed post

doctorates in previous years.)

Response Rates

Table 2 shows the number of assistant and open rank

faculty positions advertised in 2011 by departments

that responded versus departments that did not

respond to the survey. Responding departments

advertised more than 70 percent of all jobs.

Table 3 includes two units of analyses, departments

and jobs. The response rate for each type of unit

of analysis is similar, because most departments

advertised only one job. Freestanding sociology

departments advertised the most jobs. These

departments also had the highest response rates (86

percent). The second largest number of departments

and job advertisements were from non-sociology

departments, including criminal justice, government

and public affairs, international studies, cultural

and ethnic studies, and communication. They also

include schools of business, in which sociologists are

often hired to teach courses such as organizational

analysis. Non-sociology departments or schools

likely advertised their jobs in other disciplinary

job banks along with the ASA Job Bank. These

departments had signifcantly lower response

rates than did sociology or joint departments (at

52 percent). Joint sociology departments (most

often coupled with anthropology or criminal justice)

placed substantially fewer ads than non-sociology

departments, but had a substantially higher response

rate (76 percent). Although there has been a decline

in the response rate since 2009, the 2010 response

rate is substantially higher than other disciplines (for

example, economics had a 43 percent response rate

to its latest survey).

The remainder of the fndings presented in this

brief is limited to the 71 percent of departments that

responded to the Job Bank Survey, providing us with

information about 304 of the 427 jobs advertised.

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2010.

1

Total positions advertised may be higher than shown due

to many recruiters placing advertisements in 2010 for an

unspecifed multiple number of openings.

Table 1: Positions Advertised by U.S.

Institutions in 2010

1

Type of Position Total Advertised

Academic 482

Instructor/Lecturer 37

Assistant Professor 303

Associate Professor 6

Full Professor 2

Open/Multiple Rank 125

Unspecifed Rank 9

Nonacademic 212

Sociological Practice 80

Postdoc/Fellowship 88

Other Academic (Admin) 41

Multiple Position Types 3

Total Positions Advertised 694

Table 2: Assistant and Open Rank Faculty

Positions Advertised in 2010

1

Total

Departments

Total Jobs

N % N %

Respondents 239 71 304 71

Non-Respondents 99 29 123 29

All Departments 338 100 427 100

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2009 and 2010.

1

Excludes foreign institutions.

American Sociological Association, Department of Research & Development 3

Te Job Search Process

Searches were conducted for 99 percent of the

assistant and open rank positions in departments that

responded to the survey, for a total of 300 searches

about which we have information. This percentage

was about the same as for the previous year, but

the percentage of successful searches in which a

candidate was hired was somewhat lower than in

2009 (80 percent versus 86 percent). However, the

percent of successful searches were substantially

higher in both years than in 2008 (69 percent). In

2010, the percentage of jobs that were canceled

after the search began was relatively low, but not

as low as in the prior year (7 percent compared to 4

percent). Table 4 shows the 2010 fgures. Although

slightly lower than the previous year, in 2010, fully 8

out of 10 jobs ended successfully, with the hiring of a

candidate.

Jobs Filled

The academic job market is a multi-step process that

includes beginning a search, bringing in candidates

for interviews, making job offers, and flling positions.

We also asked hiring departments whether the

position was flled at the assistant rank, and for the

frst time, whether a sociologist was hired. Figure 2

illustrates this process and shows the attrition at each

stage. Not all schools conduct searches for advertised

positions, often because the positions are canceled

or the search is suspended. Not all searches yield a

consensus candidate. Not all candidates accept an

offer. And, not all successful searches result in the

hiring of sociologists. Given the multiplicity of stages

that take place before a hire is made, it is unrealistic

to expect that 100 percent of advertisements will

translate into hires. During 2010, the overall yield rate

(hires/advertisements) for assistant professor or open

hire positions and the yield for job searches (hires/

Table 3: Assistant and Open Rank Faculty Positions Advertised in 2010 by Type

of Department

1

Departments Jobs

Type of Department

Total

Departments

Placing

Advertisements

Response Rate

(%)

Total Jobs

Advertised

Jobs Advertised

by Responding

Departments

(%)

Freestanding Sociology 133 86 167 87

Joint Sociology 75 76 91 77

Non-sociology 126 52 165 53

Unknown Type 4 25 4 25

All Departments 338 71 427 71

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2009 and 2010.

1

Excludes foreign institutions.

Table 4: Searches Conducted by

Departments in 2010 (Responding

Departments Only)

N %

Total Jobs Advertised by

Responding Departments

304 100

Searches Conducted 300 99

Successful 244 80

Later Canceled or

Suspended

22 7

Not Filled for Other

Reasons

29 10

Not Filled for Reasons

Unknown

6 2

Searches Not Conducted 3 1

Search Conducted, but

Hiring Status Not Given

2 1

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2009 and 2010.

Moving Toward Recovery: Findings from the 2010 Job Bank Survey 4

searches) were both approximately 8 out of 10. The

yield was slightly lower than in 2009 when the overall

yield rate was 8.2 out of 10, and yield for job searches

was approximately 8.6 out of 10.

The highest rate of slippage in the job search process

was between the job offer and the job acceptance, with

89 percent of offers made resulting in candidates hired.

This percentage was slightly lower than in the previous

year (93 percent). Of the 244 successful searches in

2010, about 82 percent were flled by sociologists. This

number may be an overestimate since the response

rate for jobs outside of sociology departments was only

52 percent, and these departments are probably less

likely to hire sociologists. For example, as one chair of

a criminal justice department explained,

We actually advertised for three criminal justice

assistant professor positions. All three positions

have been flled, and one of the three new

assistant professors is a sociologist.

In some cases, sociologists were the preferred hire but

did not accept the job. Another chair stated:

A sociologist was the top choice for the

position and a letter of offer was extended. The

sociologist did not accept the offer, so we offered

it to the second person on the list and that

person was a political scientist.

Jobs Not Filled

A slightly higher percentage of jobs went unflled

in 2010 than in 2009 (19 percent compared to 16

percent) but the rates in both years were higher than

in 2008 (with 29 percent unflled). Table 5 details

reasons why departments or schools were unable to

fll positions. In 2009, the most common reason for

unflled positions was that the search was canceled

or suspended. Close to one-half (46 percent) of the

48 unflled positions was the result of cancellations or

suspensions. Likewise, these were the most common

reason for unflled positions in 2010, but the share was

lower than in the previous year (39 percent). As one

chair complained,

This was one of the more aggravating

experiences of my academic career. I had

resisted beginning this search because I feared

there werent funds for it, but my Dean and

Provost insisted. Two weeks before the search

closed, when applications were coming in at a

rate of something like 10 a day, we were told the

funding had been rescinded. I had to write to

everyone whod applied, apologizing profusely.

I may also have permanently damaged my

relations with the Dean and Provost, because

I told them in uncensored terms what I thought

of their leadership abilities. They said the

position was simply postponed, but now theyre

American Sociological Association, Department of Research & Development 5

Figure 2: The Hiring Process for Assistant and Open Rank Positions Advertised Through

the Job Bank (Responding Departments Only)

Source: ASA Survey of Academic Employers, 2009 and 2010.

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

304

300

286

273

244

225

200

57

Total Jobs

Advertised

Searches

Conducted

Interviews

Conducted

Candidates

Hired

Offers Made

Hired at the

Assistant

Rank

Hired a

Sociologist

Jobs Not

Filled

acknowledging that were not going to get it back

this coming year. I dont expect to see us doing

any hiring in the next 2-3 years minimum.

A higher percentage of job candidates turned down

jobs than in the prior year (28 percent compared to 21

percent), perhaps because the job market was better

in 2010 and they received more than one offer. As one

chair stated,

We interviewed four candidates, made three

consecutive offers, and when unsuccessful,

postponed the search until the following year.

This summer at [the ASA Annual Meeting] were

restarting the search.

There was also an increase in the percentage of jobs

that were unflled because the department could not

agree on a candidate or could not fnd one that was

well-qualifed enough for the positions (19 percent of

unflled jobs compared to 13 percent in 2009).

Variation Across Institutions

Thus far, we have seen the results of the hiring

process for all types of institutions. In Table 6 we

examine the job search process among different

types of institutions. We use the 2005 Carnegie

classifcation system to categorize these institutions.

A smaller percentage of jobs were flled by all types of

institutions than in the previous year, except at Very

High Research or Research Extensive institutions,

where there was essentially no change (flling 78

percent of jobs in 2010 compared to 77 percent in

2009). These institutions, which have the highest

number of faculty per department, advertised the

largest number of jobs, and this number was higher

than in 2009 (113 jobs compared to 98 jobs). While

78 percent of those jobs were flled in 2010 (about

the same that were flled in 2009), this percentage

was slightly smaller compared to other types of

Table 5: Reasons Why Assistant and Open

Rank Faculty Positions Were Not Filled in

2010 (Responding Departments Only)

N %

Total Jobs Not Filled 57 100

Canceled 13 23

Suspended 9 16

Search Still in Progress 2 4

Candidate Turned Down Offer 16 28

No Agreement as to Candidate

or Lack of Qualifed Candidates

11 19

Reason Not Given 6 11

Source: ASA Job Bank Survey, 2010.

1

Respondents were asked to select all reasons why a position

was not flled. In most cases, multiple reasons were selected

where offers were turned down and the search was ultimately

canceled or suspended, or that the pool of qualifed candidates

was exhausted once the offer was turned down..

Table 6: Assistant and Open Rank Faculty Positions Advertised in 2010 by Type of Department

Type of Institution

Total

Depts.

Responding Departments

Response

Rate

(%)

Number

of Jobs

Advertised

Searches

Conducted

Candidates

Brought In

Offers

Made

Jobs Filled

(%)

Very High Research 115 75 113 111 105 99 78

High Research/Doctorate 66 83 80 79 75 71 81

Masters 90 67 70 70 67 66 80

Baccalaureate 56 61 37 37 36 34 86

Associates/Special Focus 11 36 4 3 3 3 75

All Departments 338 71 304 300 286 273 80

Source: ASA Job Bank Survey, 2010

Moving Toward Recovery: Findings from the 2010 Job Bank Survey 6

advertising institutions. It may be that Very High

Research Schools are more selective than the other

types of institutions because they have access

to more graduate students and adjunct faculty to

teach courses if they do not fll a position. Both High

Research/Doctorate and Masters Comprehensive

schools that responded to the survey advertised more

jobs in 2010 than in 2009 (80 compared to 55), but

had fewer searches that resulted in hires. Responding

Baccalaureate-only institutions, which have the

smallest departments on average, advertised fewer

jobs than in 2009 (37 compared to 43). Although they

advertised the fewest jobs, those Baccalaureate-only

schools that responded (61 percent) flled the highest

percentage of jobs (86 percent). This type of school

may be more likely to advertise on regional listservs,

rather than a nationally-oriented job bank. Associate

and special focus schools advertised only four jobs.

Match and Mismatch Across Specialties

Among the reasons for failure to complete searches

may be the mismatch between the specialty areas

in which departments wish to hire and the areas

in which candidates specialize. Table 7 compares

the specializations listed in all assistant and open

rank positions advertised in the Job Bank in 2010

American Sociological Association, Department of Research & Development 7

Table 7: Comparison of Specializations Listed in All Assistant and Open

Rank Job Bank Advertisements in 2010 to Areas of Interest Selected by PhD

Candidates on ASA Membership Forms in 2010.

Specialization

Advertised

Specialties (N=427)

Areas of Student

Interest in 2010

(N=4,511)

Difference in %

of Specialties

Compared to

Interest

1

% Rank % Rank Percent

Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance 30.9 1 17.9 7 13.0

Politics and Social Change 23.0 2 33.9 2 -10.9

Place and Environment 23.0 3 13.7 10 9.3

Race and Ethnicity 22.5 4 19.2 6 3.3

Medicine and Health 20.8 5 12.3 12 8.5

Inequalities and Stratifcation 19.7 6 34.7 1 -15.0

Quantitative Approaches 19.4 7 11.5 14 7.9

Work, Economy and Organizations 16.9 8 20.4 4 -3.5

Application and Practice 16.6 9 10.6 16 6.1

Theory, Knowledge, Science 12.6 10 15.0 9 -2.3

Family, Life Course, and Society 11.9 11 16.8 8 -4.8

Other Specialization 10.5 12 3.6 18 6.9

Gender and Sexuality 10.3 13 19.6 5 -9.3

Sociology of Culture 8.4 14 24.3 3 -15.8

Comparative and Historical Approaches 7.7 15 12.5 11 -4.7

Open Specialization/Not Specifed 7.0 16.0 N/A N/A N/A

Social Psychology and Interaction 6.6 17 11.5 13 -4.9

Qualitative Approaches 6.1 18 10.6 15 -4.5

Population and Ecology 5.6 19 6.8 14 -1.2

Average specialty areas per job = 2.8

Source: ASA Job Bank Survey, 2010

1

When the percent of specialties advertised exceeds the percent of students interested in that area, the difference

in percent is positive. When the difference in percent is negative, interest exceeds availability.

with those listed by PhD candidates on their ASA

membership forms (As previously noted, both were

coded using the ASA list of specialty areas on the

membership form). Of the areas listed, there was

more than a fve percent gap in 10 cases and less

than a fve percent gap in the eight other cases.

We also coded advertisements that did not list

specializations, or stated that the specialization

was open. There is no comparable category for this

variable on the ASA membership form. There were

four areas with more than a 10 percent gap. The

largest gap was in sociology of culture which ranked

as the 3

rd

highest specialty area among ASA PhD

candidates but only 14

th

highest among advertising

departments. The second largest gap was in

inequalities and stratifcation (including race, class,

and gender), which was the highest ranked specialty

among students, but was the 6

th

most frequent

specialty in Job Bank advertisements. The 3

rd

largest

gap (13 percent) was in social control, law, crime,

and deviance. Although it was the most frequently

sought specialty by advertising departments, it was

ranked 7

th

highest among students. The result was

an encouraging market for those new PhDs who

specialized in this area. As one chair noted,

The market is very competitive for sociologists

with backgrounds in criminology. We brought 14

people to campus for two positions and made six

offers that were declined. We fnally were able to

hire two people at the end of the search.

Population and ecology had the smallest

gap (although it was also listed in the fewest

advertisements). Theory, knowledge and science

had about a two percent gap, and race and ethnicity

had about a three percent gap. The differences may

not be as large as the table suggests, however,

because departments advertised an average of 2.8

specialties and students were permitted to list up to

four specialties on their membership form. Further,

the demand for specialties may not remain stable

from year to year.

New PhD sociologists can be somewhat more

optimistic about the current job market for assistant

professors with a 32 percent increase in the number

of jobs advertised in the 2010 Job Bank, compared

to the 35 percent dip in the previous year. There

were more academic jobs advertised and fewer

jobs advertised in applied, research, and policy

positions than in 2009. Early indications suggest a

continued improvement in the number of positions

being advertised in 2011. In addition, supply-side

competition may have lessened because there was

a drop in the number of new PhDs. However, those

PhDs who did not obtain jobs because of the poor job

market in 2009 probably engaged in a job search this

year, so that the jobs per person was probably not

as high as reported. Moreover, if there is a group of

advanced graduate students awaiting improvements

in the job market, then the apparent decline in supply

of new PhDs may be temporary. Nonetheless, the

data do not indicate that the discipline as a whole

is producing too many PhDs, the source of an on-

going debate for at least a decade, although reducing

the number of graduate students accepted has been

the policy of numbers of universities over the last year

or so (Jaschick 2009). A positive job market for new

PhDs is especially likely if they and their departments

consider jobs outside of the academy doing applied,

research, and/or policy work as well as academic

jobs. The comments from chairs also suggest that

sociologists are competitive for jobs in academic

departments outside of sociology, especially if

graduate students consider, and departments support,

some switch in specialty areas to include at least one

of those where there is an undersupply of sociologists

(such as criminal justice, environmental studies,

public policy, and quantitative methods). Finally,

we hope for a higher response rate next year by

starting the survey before summer break when more

department chairs may be at their offces.

Moving Toward Recovery: Findings from the 2010 Job Bank Survey 8

CONCLUSIONS

References

Jaschik, Scott. 2011. Recovery in Political Science. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved July 28, 2011 (http://www.

insidehighered.com/news/2011/07/28/political_science_job_market_shows_signs_of_recovery).

Jaschik, Scott. 2009.Top Ph.D. Programs, Shrinking. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved July 22, 2010 (http://www.

insidehighered.com/layout/set/print/news/2009/05/13/doctoral).

Schmidt, Peter. 2011. Historians Continue to Face Tough Job Market. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved July 1,

2011 (http://chronicle.com/article/Historians-Continue-to-Face/125794/).

Spalter-Roth, Roberta, Jerry Jacobs, and Janene Scelza. 2009. Too Many or Too Few PhDs? Employment Opportunities

in Academic Sociology. Retrieved July 21 ( http://www.asanet.org/images/research/docs/pdf/Too%20Many%20or%20

Too%20Few%20PhDs.pdf).

Spalter-Roth, Roberta, Jerry Jacobs, Janene and Scelza. 2010. Still a Down Market? Findings From the 2009/2010

Job Bank Survey. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. Retrieved July 21, 2011 (http://www.asanet.org/

research/ASAJobBankStudy09.pdf).

American Sociological Association, Department of Research & Development 9

Title Date Format

The Impact of Cross-Race Mentoring for Ideal and Alternative PhD Careers in Sociology 2011 PDF

Sociology Masters Graduates Join the Workforce 2011 PDF

Are Masters Programs Closing? What Makes for Success in Staying Open? 2011 PDF

Falling Behind: Sociology and Other Social Science Faculty Salaries, AY 2010-2011 2011 PDF

A Decade of Change: ASA Membership From 2000 - 2010 2011 PDF

Findings From ASA Surveys of Bachelors, Masters and PhD Recipients: Implications for Departments in a Jobless

Recovery

2011 PPT

Homosociality or Crossing Race/Ethnicity/Gender Boundaries? Pipeline Interventions and the Production of Scholarly

Careers

2011 PPT

Networks and the Diffusion of Cutting-Edge Teaching and Learning Knowledge in Sociology 2011 PDF

The Gap in Faculty Pay Between Private and Public Institutions: Smaller in Sociology Than in Other Social Sciences 2010 PDF

Still a Down Market: Findings from the 2009/2010 Job Bank Survey 2010 PDF

From Programs to Careers: Continuing to Pay Attention to the Master's Degree in Sociology 2010 PDF

Teaching Alone? Sociology Faculty and the Availability of Social Network 2010 PDF

Mixed Success: Four Years of Experiences of 2005 Sociology Graduates 2010 PDF

Sociology Faculty See Smaller Raises but Still Outpace Infation in AY 2009-2010: Other Social Science Disciplines Not

Able to Recoup Losses

2010 PDF

What's Happening in Your Department? Department Resources and the Demand Side of Hiring 2010 PDF

Down Market? Findings from the 2008 ASA Job Bank Study 2009 PDF

Paying Attention to the Master's Degree in Sociology 2009 PDF

What's Happening in Your Department With Assessment? 2009 PDF

Sociology Faculty Salaries AY 2008/09: Better Than Other Social Sciences, But Not Above Infation 2009 PDF

Idealists v. Careerists: Graduate School Choices of Sociology Majors 2009 PDF

What's Happening in Your Department: Who's Teaching and How Much? 2009 PDF

Decreasing the Leak from the Sociology Pipeline: Social and Cultural Capital to Enhance the Post-Baccalaureate Soci-

ology Career

2009 PDF

What's Happening in Your Department? A Comparison of Findings From the 2001 and 2007 Department Surveys 2008 PDF

PhD's at Mid-Career: Satisfaction with Work and Family 2008 PDF

Too Many or Too Few PhDs? Employment Opportunities in Academic Sociology 2008 PDF

Pathways to Job Satisfaction: What happened to the Class of 2005? 2008 PDF

Sociology Faculty Salaries, AY 2007-08 2008 PDF

How Does Our Membership Grow? Indicators of Change by Gender, Race and Ethnicity by Degree Type, 2001-2007 2008 PDF

What are they Doing With a Bachelor's Degree in Sociology? 2008 PDF

The Health of Sociology: Statistical Fact Sheets, 2007 2007 PDF

Sociology and Other Social Science Salary Increases: Past, Present, and Future 2007 PDF

Race and Ethnicity in the Sociology Pipeline 2007 PDF

Beyond the Ivory Tower: Professionalism, Skills Match, and Job Satisfaction in Sociology [Power Point slide show] 2007 PPT

What Sociologists Know About the Acceptance and Diffusion of Innovation: The Case of Engineering Education 2007 PDF

Resources or Rewards? The Distribution of Work-Family Policies 2006 PDF

Profle of 2005 ASA Membership 2006 PDF

What Can I Do with a Bachelors Degree in Sociology? A National Survey of Seniors Majoring in SociologyFirst

Glances: What Do They Know and Where Are They Going?

2006 PDF

Race, Ethnicity & American Labor Market 2005 PDF

Race, Ethnicity & Health of Americans 2005 PDF

The Best Time to Have a Baby: Institutional Resources and Family Strategies Among Early Career Sociologists 2004 PDF

Academic Relations: The Use of Supplementary Faculty 2004 PDF

Te following are research briefs and reports produced by the ASAs Department of Research and Development for dissemination in a variety

of venues and concerning topics of interest to the discipline and profession. Tese briefs are located at http://www.asanet.org/research/briefs_

and_articles.cfm. You will need Adobe Reader to view our PDFs.

research@asanet.org

Department of Research & Development

American Sociological Association

También podría gustarte

- Linear and Generalized Linear Mixed Models and Their ApplicationsDe EverandLinear and Generalized Linear Mixed Models and Their ApplicationsAún no hay calificaciones

- Stemfinalyjuly14 1.pdf-126009783 PDFDocumento10 páginasStemfinalyjuly14 1.pdf-126009783 PDFĐỗ Lê DuyAún no hay calificaciones

- Vocational Training For The Unemployed: Its Impact On Uncommonly Served GroupsDocumento20 páginasVocational Training For The Unemployed: Its Impact On Uncommonly Served GroupsNuroel HafnatiAún no hay calificaciones

- Artikel 6Documento24 páginasArtikel 6pandukarnoAún no hay calificaciones

- Discussion Paper Series: Perceived Wages and The Gender Gap in STEM FieldsDocumento20 páginasDiscussion Paper Series: Perceived Wages and The Gender Gap in STEM FieldsvictorAún no hay calificaciones

- sp6101 06 Uggen and Shannon 1Documento26 páginassp6101 06 Uggen and Shannon 1api-247020555Aún no hay calificaciones

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocumento19 páginasWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherAneeka FarooqiAún no hay calificaciones

- Conde-Ruiz2021 Article GenderDistributionAcrossTopicsDocumento40 páginasConde-Ruiz2021 Article GenderDistributionAcrossTopicsProdeep kumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review of Unemployment in MalaysiaDocumento7 páginasLiterature Review of Unemployment in Malaysiafat1kifywel3100% (1)

- Journal 2Documento49 páginasJournal 2IcookiesAún no hay calificaciones

- Middle Level SkillsDocumento1 páginaMiddle Level SkillsDionesio OcampoAún no hay calificaciones

- Example of Research PaperDocumento8 páginasExample of Research PaperAbidullahAún no hay calificaciones

- A Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit ExtensionsDocumento41 páginasA Quantitative Analysis of Unemployment Benefit ExtensionsAmmar SalihovicAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of Government Policy On Economic GrowthDocumento11 páginasThe Impact of Government Policy On Economic GrowthGanesh R Nair100% (1)

- MSDM PlacementDocumento12 páginasMSDM PlacementMeryana Santya ParamitaAún no hay calificaciones

- dp10788 000Documento51 páginasdp10788 000RehanAún no hay calificaciones

- PHD Career Preferences - PLoS One - 2012Documento9 páginasPHD Career Preferences - PLoS One - 2012Feyza Nur ArslanAún no hay calificaciones

- Differences by Degree: Evidence of The Net Financial Rates of Return To Undergraduate Study For England and WalesDocumento28 páginasDifferences by Degree: Evidence of The Net Financial Rates of Return To Undergraduate Study For England and WalesmasithreadAún no hay calificaciones

- Do Labor Statistics Depend On How and To Whom The Questions Are Asked? Results From A Survey Experiment in TanzaniaDocumento30 páginasDo Labor Statistics Depend On How and To Whom The Questions Are Asked? Results From A Survey Experiment in TanzaniarussoAún no hay calificaciones

- Rudakov Et Al 2019Documento33 páginasRudakov Et Al 2019trejo.cesarAún no hay calificaciones

- A Literature Review of Employment Programs Impact On RecidivismDocumento31 páginasA Literature Review of Employment Programs Impact On RecidivismMaisha Tabassum AnimaAún no hay calificaciones

- JRD 2022 V1N1 P02Documento10 páginasJRD 2022 V1N1 P02Joan Perolino MadejaAún no hay calificaciones

- Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment Among NursesDocumento37 páginasRelationship Between Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment Among Nurseslinulukejoseph100% (1)

- January 2019 - December 2019Documento19 páginasJanuary 2019 - December 2019Princess Aiza MaulanaAún no hay calificaciones

- Todays Education Tomorrows JobDocumento9 páginasTodays Education Tomorrows JobRozy SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Review of Job Portal in Recuirement Process Life CycleDocumento3 páginasReview of Job Portal in Recuirement Process Life Cyclerutwik ankusheAún no hay calificaciones

- Graduate Unemployment Literature ReviewDocumento4 páginasGraduate Unemployment Literature Reviewc5pbp8dk100% (1)

- A Comparative Analysis of Job Motivation and Career Preference of Asian Undergraduate StudentsDocumento23 páginasA Comparative Analysis of Job Motivation and Career Preference of Asian Undergraduate StudentsnelsonAún no hay calificaciones

- "Today's Education, Tomorrow's Job": A Research PaperDocumento9 páginas"Today's Education, Tomorrow's Job": A Research PaperRozy SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Balafoutas Sutter 2010Documento35 páginasBalafoutas Sutter 2010Zurdo de GuadalupeAún no hay calificaciones

- HardTimes2015 ReportDocumento52 páginasHardTimes2015 ReportrupertaveryAún no hay calificaciones

- CEP Discussion PaperDocumento41 páginasCEP Discussion PaperNicholas See TongAún no hay calificaciones

- Making The Case For A Higher Minimum WageDocumento8 páginasMaking The Case For A Higher Minimum WageRabeya Bushra KonaAún no hay calificaciones

- Barra 2016Documento23 páginasBarra 2016anisbouzouita2005Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Effects of Extracurricular Activities & Gpa On Employability of Egyptian Students of Public & Private UniversitiesDocumento19 páginasThe Effects of Extracurricular Activities & Gpa On Employability of Egyptian Students of Public & Private UniversitiesMsa-Management Sciences JournalAún no hay calificaciones

- Yu Shunxian 2016 ResearchpaperDocumento41 páginasYu Shunxian 2016 Researchpapertahsina akhterAún no hay calificaciones

- Unveiling The Aftermath of Education-Job Mismatch Among Uic Business Administration GraduatesDocumento46 páginasUnveiling The Aftermath of Education-Job Mismatch Among Uic Business Administration GraduatesAndreaAún no hay calificaciones

- Literatures and StudiesDocumento6 páginasLiteratures and StudiesRynefel ElopreAún no hay calificaciones

- Labour Economics Literature ReviewDocumento7 páginasLabour Economics Literature Reviewc5sd1aqj100% (1)

- Dei DegringoladeDocumento3 páginasDei DegringoladestupefyinjonesAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter II To IVDocumento21 páginasChapter II To IVJuliet ToriagaAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review On Unemployment and CrimeDocumento7 páginasLiterature Review On Unemployment and Crimeluwahudujos3100% (1)

- Research Paper Unemployment RateDocumento5 páginasResearch Paper Unemployment Rateafnhinzugpbcgw100% (1)

- Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Nurses and Midwives of DohDocumento12 páginasJob Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Nurses and Midwives of Dohkaori mendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Marginal Labor Supply DisincentivesDocumento67 páginasThe Marginal Labor Supply DisincentivesErlina RahmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Keith Research Paper WordDocumento7 páginasKeith Research Paper Wordapi-301968534Aún no hay calificaciones

- Pellizzari 2004Documento44 páginasPellizzari 2004Valentina CroitoruAún no hay calificaciones

- How Effevtive Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing CountriesDocumento28 páginasHow Effevtive Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing CountriesRIFDAAún no hay calificaciones

- Tracer Study of TRISDocumento5 páginasTracer Study of TRISLyra AlamoAún no hay calificaciones

- TTR SchoolstaffingDocumento16 páginasTTR SchoolstaffingNational Education Policy CenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Chap 2Documento7 páginasChap 2Barry Hilton PatnettAún no hay calificaciones

- Annotated Bibliography FinalDocumento6 páginasAnnotated Bibliography FinalMast SoftechAún no hay calificaciones

- Education Supports Racial and Ethnic Equality in STEM: Executive SummaryDocumento11 páginasEducation Supports Racial and Ethnic Equality in STEM: Executive Summarybrian_d_fungAún no hay calificaciones

- Working Papers: Declining Labor Turnover and TurbulenceDocumento45 páginasWorking Papers: Declining Labor Turnover and TurbulenceTBP_Think_TankAún no hay calificaciones

- StatisticsDocumento1 páginaStatisticsTaha BhalamAún no hay calificaciones

- Jobsatisfaction, Organisational Commitment, NurseDocumento37 páginasJobsatisfaction, Organisational Commitment, NurselinulukejosephAún no hay calificaciones

- Wilson - Dropout - Protocol - CSRDocumento35 páginasWilson - Dropout - Protocol - CSRAnna MaryaAún no hay calificaciones

- Rocío Pérez Sauquillo Cano Coloma W1465490 Academic EnglishDocumento6 páginasRocío Pérez Sauquillo Cano Coloma W1465490 Academic EnglishRo SsaAún no hay calificaciones

- Labor Market Transitions and The Availability of Unemployment InsuranceDocumento37 páginasLabor Market Transitions and The Availability of Unemployment InsuranceTBP_Think_TankAún no hay calificaciones

- Ndisio - Assesment of Locally Cultivated Groundnut (Arachis Hypogaea) Varieties For Susceptibility To Aflatoxin Accumulation in Western KenyaDocumento95 páginasNdisio - Assesment of Locally Cultivated Groundnut (Arachis Hypogaea) Varieties For Susceptibility To Aflatoxin Accumulation in Western KenyaMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Straw ManDocumento80 páginasStraw ManMind Props100% (2)

- Road Safety Policy GuidelinesDocumento75 páginasRoad Safety Policy GuidelinesMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Public Finance and TaxationDocumento5 páginasPublic Finance and TaxationMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Academic WorkloadDocumento53 páginasAcademic WorkloadMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Accredition FormDocumento2 páginasAccredition FormMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Accommodation Guide QLD Nov 2013Documento16 páginasAccommodation Guide QLD Nov 2013Mind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- 2014 Tuition Fee Advice For International Students Studying at UqDocumento1 página2014 Tuition Fee Advice For International Students Studying at UqMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Syllabus 3Documento6 páginasSyllabus 3Mind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- SW HandbookDocumento100 páginasSW HandbookMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Post Study Work Arrangements FAQDocumento5 páginasPost Study Work Arrangements FAQMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Qut SW80 26537 Dom CmsDocumento2 páginasQut SW80 26537 Dom CmsMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Qut SW80 26537 Dom Cms UnitDocumento5 páginasQut SW80 26537 Dom Cms UnitMind PropsAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis 2011 LaidlawDocumento253 páginasThesis 2011 LaidlawTiến NguyễnAún no hay calificaciones

- The Vulnerability of Interdependent Critical Infrastructures SystemsDocumento103 páginasThe Vulnerability of Interdependent Critical Infrastructures SystemsChristiansen SavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Extending Conceptual Boundaries Work Voluntary Work and EmploymentDocumento22 páginasExtending Conceptual Boundaries Work Voluntary Work and EmploymentJoy JoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Historicist Conceptions of RationalityDocumento17 páginasHistoricist Conceptions of RationalityArfaida LadjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Film and Litteracture ConnectionDocumento15 páginasFilm and Litteracture Connectionazer comel100% (1)

- The Changing Role of The University in The Production of New KnowledgeDocumento10 páginasThe Changing Role of The University in The Production of New KnowledgeAline LopesAún no hay calificaciones

- St. Mary's College of Marinduque Isok 1 Boac, Marinduque Integrated Basic Education Department S.Y. 2021-2022Documento7 páginasSt. Mary's College of Marinduque Isok 1 Boac, Marinduque Integrated Basic Education Department S.Y. 2021-2022Mariyya Monikka Fernandez JandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Contributions of Classical Thinkers On Social PsychologyDocumento9 páginasContributions of Classical Thinkers On Social PsychologyKaran KujurAún no hay calificaciones

- Ariail Reed Isaac. Power Relational, Discursive, and Performative DimensionsDocumento27 páginasAriail Reed Isaac. Power Relational, Discursive, and Performative DimensionsJuan Pablo Peñuela ParraAún no hay calificaciones

- (Caroline Joan S. Picart) From Ballroom To DanceSpDocumento180 páginas(Caroline Joan S. Picart) From Ballroom To DanceSpchimcuccu9944Aún no hay calificaciones

- riccardo,+OP04319 Cambio 2020 20 05-10753winter 41-52Documento12 páginasriccardo,+OP04319 Cambio 2020 20 05-10753winter 41-52Saif NAún no hay calificaciones

- Learning Activity SheetDocumento12 páginasLearning Activity SheetJessa GazzinganAún no hay calificaciones

- Wa0005.Documento14 páginasWa0005.Shambhavi MishraAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 1.1 - Social Psychology As A DisciplineDocumento38 páginasChapter 1.1 - Social Psychology As A DisciplineKARLA MAE REVANOAún no hay calificaciones

- SHS Core Understanding Culture Society and PolitiDocumento8 páginasSHS Core Understanding Culture Society and PolitiNerriza VinzeAún no hay calificaciones

- What I Learned in Adult Development - A ReflectionDocumento7 páginasWhat I Learned in Adult Development - A ReflectionJonathan H WestAún no hay calificaciones

- The Triumph of The Moon - Ronald HuttonDocumento446 páginasThe Triumph of The Moon - Ronald HuttonMahaotAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review Sociology ExampleDocumento5 páginasLiterature Review Sociology Exampleea1yw8dx100% (1)

- Urban Sociology & Industrial SociologyDocumento4 páginasUrban Sociology & Industrial SociologyPragnyaraj BisoyiAún no hay calificaciones

- DISS - Module-3 - Quarter 2Documento10 páginasDISS - Module-3 - Quarter 2Alex Sanchez100% (1)

- Horkheimer On Critical Theory 1937 PDFDocumento28 páginasHorkheimer On Critical Theory 1937 PDFKostas Bizas100% (1)

- Ucsp Lesson 1Documento2 páginasUcsp Lesson 1Lucille SeropinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Q2 Intro To Philo 12 - Module 3Documento30 páginasQ2 Intro To Philo 12 - Module 3Cris FalsarioAún no hay calificaciones

- Functions of The FamilyDocumento8 páginasFunctions of The FamilyWilliam SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Exploration of Human Rights: When Human Rights Become Part of The ProblemDocumento14 páginasCritical Exploration of Human Rights: When Human Rights Become Part of The ProblemInformerAún no hay calificaciones

- UCSP Module I Anthropology, Sociology, and Political Science No Pics PDFDocumento7 páginasUCSP Module I Anthropology, Sociology, and Political Science No Pics PDFStudy with Ser Gi100% (1)

- ED 202 MODULE MasbanoDocumento80 páginasED 202 MODULE MasbanoLowela Joy AndarzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Max Weber Bureaucratic Theory PDFDocumento1 páginaMax Weber Bureaucratic Theory PDFVeronica TanAún no hay calificaciones

- Friedman-Legal Culture and Social Development PDFDocumento17 páginasFriedman-Legal Culture and Social Development PDFCésar Antonio Loayza VegaAún no hay calificaciones

- Philosophical and Sociological Bases of EducationDocumento167 páginasPhilosophical and Sociological Bases of EducationChethan C E100% (1)