Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Toronto: Gerald Ferguson at Wynick/Tuck

Cargado por

Angelica Gonzalez0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

26 vistas2 páginasmike nelson

Título original

ContentServer (13)

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentomike nelson

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

26 vistas2 páginasToronto: Gerald Ferguson at Wynick/Tuck

Cargado por

Angelica Gonzalezmike nelson

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 2

s

Often, the compositions in

Reid's watercoiors seem to result

more from physical process than

formal intent; she lets gravity and

other properties of the medium

play a major role. In this way, she

arrives at a relaxed, organic inter-

pretation of Minimalist form.

Meiissa E. Feidman

TORONTO

Gerald Ferguson

at Wynick/Tuck

Gerald Ferguson is perhaps best

known to Canadian art viewers

for his 7,000,000 Grapes instal-

lation at the National Gallery of

Canada in 2000. In that work the

artist designed a stencil of 40

grapes, borrowing the composi-

tion of the fruit from the still life

that appears in Picasso's Les

Demoiselles d'Avignon. Using

a roller and black enamel paint,

the stencil was applied 250

times on each of a hundred

48-inch-square canvases. The

individual paintings are almost

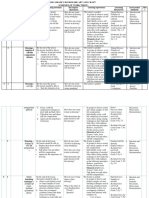

Gerald Ferguson; A/o. 2, 2002. enamel on drop

Cloth, 78 by S2 Inches; at Wynick/Tuck.

entirely black, except for the

occasional small bit of raw oan-

vas. Hung on the wall in a grid,

the paintings resemble a starry

night skythe gorgeous and

serendipitous result of a very

mechanical process.

In his recent show at Wynick/

Tuck, Ferguson continues to

develop his unique brand of

process painting in which beauty

is the by-product of banal, anti-

vtrtuosic means. In 11 new

paintings (all 2003), rather than

using a stencil, the artist frot-

taged a length of 2-inch welded

steel chain by placing it under a

canvas in various positions and

passing over the top with a roller

and black paint. Instead of plain

canvas, Ferguson employed

fabric drop cloths that had been

used by housepainters. With

their spills and marks, the

drop cloths were themselves

ready-made paintings. In the

beautiful, opportune "collabora-

tions," Ferguson simply adds

his signature with the frottaged

chain.

The drop cloth in No. 2 {78 by

92 inches), an old sheet, is pat-

terned with small, yellow flowers.

Brilliant pink and blue splotches of

paint punctuate the surface.

Ferguson laid a length of the 2-

inch chain under this sheet in

even rows. The result is an intri-

cate, abstract pattern of thou-

sands of aggressive dashes.

No. 17 {80 by 92 inches) is made

on a white drop cloth bearing four

black, square outlines in a row

across the top and black paint spills

at the bottom right and top left. The

chain marks are less dense than in

No. 2; there is only a delicate pat-

tern of thin, black vertical lines over

the surface. No. 27(59 by 53 inch-

es) is one of the more

spare compositions. A

cream-colored cloth is

frottaged with thin black

lines. There are only

three interruptions to

the otherwise airy com-

position: a thick red line

cuts through the middle

of the canvas; a thinner

black line enters from

the bottom right; and a

black L shape, tilted

slightly to the left,

appears near the top.

In these new works,

Ferguson continues to

create visually complex

paintings using the

most humble of materi-

als and processes.

Melissa Kuntz

OXFORD

Mike Nelson at the

Modem Art Museum

British artist Mike Nelson has

made his name as the king of sal-

vage installation. This magpie fre-

quenter of flea markets and thrift

stores utilizes everything from

reclaimed doors to discarded tele-

phones and broken toys to create

his disorienting, space-devouring

works. Unlike previous Nelson

adventures, notably in the Venice

Biennale and Turner Prize exhibi-

tions of 2001, his latest show was

not one ail-encompassing environ-

ment but a show in three acts,

hence the (punning) title, 'Triple

Bluff Canyon."

First came a disheveled cinema

foyer with boarded-up box office

and dog-eared posters for Alien,

an inauspicious no-man's-land of

a beginning with three numbered

doors urging the visitor to choose

his or her own multiplex destiny.

Just one of the exits worked, but

only to reveal the unpainted

wooden structure ot the false

lobby. Nelson's first "bluff" being a

film set of a cinema.

Further on, the next space again

took us behind the scenes, this

time to the artist's front-room-cum-

studio in South London, which he

re-created right up to the ceiling

rose. This was not the first time

Nelson displayed his studio as a

set within an exhibition, but here

one was not granted entrance and

could merely peer into the installa-

tion through the glassless window

bays. This shift from total immer-

sion to theatrical distance sug-

gests Nelson wants the act of

viewing to be as important as any

phenomenological concerns. A

projector on a table in the room

bounced a film off a convex mirror

and back to the gallery wall, but

this was no cinematic experience.

Instead, a little-known U.S. con-

spiracy theorist named Jordan

Maxwell ranted on about the

Knights Templar and the llluminati,

claiming that these groups had

been plotting a New World Order

with roots in ancient Egypt.

As if on cue, the next installation

offered a giant pyramidal sand

dune. A rickety, narrowing wooden

corridor that resembled a disused

mineshatt seemed to offer a pas-

sage through the tons of sand but

culminated in a Nelson trademark:

a dead end lit by a naked lightbulb.

With no way through, the viewer

was forced to retrace the path back

to the ground-floor information desk

and up a flight of stairs to the muse-

um's first floor, where the partially

submerged wooden structure was

visible in a sea of sand. The image

paid homage to Robert Smithson's

Partially Buried Woodstied{1970),

built at Kent State University, in

which earth was piled onto an exist-

ing structure until the central beam

cracked. The exhibition catalogue

highlights the connection between

Smithson's work, which was politi-

cized after student demonstrators

were killed on campus months

later, and Nelson's desert remake,

which included discarded oil drums

referencing the Iraq war and occu-

pation. However, there is another

link between the two artists.

Smithson lamented the stale

View of Mike Nelson's installation

"Triple Bluff Canyon," 2004;

at the Modern Art Museum.

atmosphere of the gallery ("muse-

ums are tombs," he onoe wrote)

and so took his work outside, while

Nelson goes some way to reinvigo-

rating the museum with works of art

that suggestively transport the out-

side world into the white cube.

Ossian Ward

PARIS

Jennifer Allora

and Guillermo Calzadilla

at Chantai Crousel

"Ciclonismo," a term invented by

this artist team, is the study of the

effect of natural phenomena, such

as cyclones, on social movements

in the Caribbean. "Histories of

power, colonization, and cross-

cultural exchanges can be told

through wind routes," explains the

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo

Calzadilla: The Nature of Conflict,

2004, used motor oii, water, mixed

mediums; at Chantai Crousel.

189

También podría gustarte

- Art Principles with Special Reference to Painting: Together with Notes on the Illusions Produced by the PainterDe EverandArt Principles with Special Reference to Painting: Together with Notes on the Illusions Produced by the PainterAún no hay calificaciones

- Turner Five letters and a postscript.De EverandTurner Five letters and a postscript.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Photo-Eye 1998 Nudes CatalogDocumento16 páginasPhoto-Eye 1998 Nudes CatalogAshutosh Kashmiri38% (8)

- Head Presidents-A Wheelchair Is Abandoned in A Corner Alongside ADocumento7 páginasHead Presidents-A Wheelchair Is Abandoned in A Corner Alongside AAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- The New Whitney MuseumDocumento3 páginasThe New Whitney MuseumJames D. BalestrieriAún no hay calificaciones

- The Goldfinch PaintingDocumento6 páginasThe Goldfinch PaintingJorge De Felipe MoreiraAún no hay calificaciones

- Basarab Nicolescu, Alexandre de Salzmann, Un Grand Artiste Oublié Du 20e SiècleDocumento69 páginasBasarab Nicolescu, Alexandre de Salzmann, Un Grand Artiste Oublié Du 20e SiècleBasarab Nicolescu100% (2)

- Early Plywood Support for George Inness PaintingDocumento5 páginasEarly Plywood Support for George Inness PaintingMaja Con DiosAún no hay calificaciones

- See Also: : Contemporary/Postmodern Art View Image ListDocumento3 páginasSee Also: : Contemporary/Postmodern Art View Image ListPedro AgudeloAún no hay calificaciones

- Printmaking - Introduction To ArtDocumento21 páginasPrintmaking - Introduction To ArtamyzonkersAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is A Print Brochure 1999Documento6 páginasWhat Is A Print Brochure 1999P FAún no hay calificaciones

- DZbookDocumento84 páginasDZbookÆl TanitocAún no hay calificaciones

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocumento2 páginasEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldpstrlAún no hay calificaciones

- Renaissance To Modern Art - ARTWORKSDocumento12 páginasRenaissance To Modern Art - ARTWORKSFarah CalimquimAún no hay calificaciones

- Gagosian - September 2022Documento10 páginasGagosian - September 2022ArtdataAún no hay calificaciones

- The Printed Image 8Documento10 páginasThe Printed Image 8PriscilaAún no hay calificaciones

- Art Unlimited - Art Basel 42Documento126 páginasArt Unlimited - Art Basel 42ninicuriosini100% (1)

- An-My LeDocumento3 páginasAn-My LeelsmddAún no hay calificaciones

- Cneed: Marc Werner Enters The Mazes Created by The Master-Builder of Reality, Mike Nelson, and Leaves in A DazeDocumento4 páginasCneed: Marc Werner Enters The Mazes Created by The Master-Builder of Reality, Mike Nelson, and Leaves in A DazeAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Prints Abound Paris in The 1890s From The Collections of Virginia and Ira Jackson and The National Gallery of Art PDFDocumento184 páginasPrints Abound Paris in The 1890s From The Collections of Virginia and Ira Jackson and The National Gallery of Art PDFMatina Karali100% (3)

- Twentieth Century English LiteratureDocumento51 páginasTwentieth Century English LiteratureYasemen KirisAún no hay calificaciones

- Collage: 1 HistoryDocumento11 páginasCollage: 1 HistorytanitartAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus Chris Video Green Los Angeles Art and The Triumph of NothingnessDocumento173 páginasKraus Chris Video Green Los Angeles Art and The Triumph of NothingnessFederica Bueti100% (3)

- Piranesi's Dark Prison TransformedDocumento28 páginasPiranesi's Dark Prison Transformedlalala100% (1)

- Soft Sculpture EventsDocumento28 páginasSoft Sculpture EventsAlabala BalaaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 28 Art Between The WarsDocumento11 páginasChapter 28 Art Between The Wars126n8xbhAún no hay calificaciones

- Art History - MidtermDocumento7 páginasArt History - Midtermalejandra.alvarez.polAún no hay calificaciones

- Childrens Book of Art PDFDocumento141 páginasChildrens Book of Art PDFIsabel Noemi Faro Coelho100% (4)

- MOMA 1967 Jan-June 0045 32Documento2 páginasMOMA 1967 Jan-June 0045 32Marcos Ortiz CasasAún no hay calificaciones

- The Return To RepresentationDocumento12 páginasThe Return To RepresentationWRONGHEARAún no hay calificaciones

- Treasury of Traditional Stained Glass DesignsDe EverandTreasury of Traditional Stained Glass DesignsCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (3)

- Bomford ColourArtScience SM PDFDocumento24 páginasBomford ColourArtScience SM PDFpoisoneveAún no hay calificaciones

- Joshua Reynolds's "Nice Chymistry": Action and Accident in The 1770s Author(s) : Matthew C. Hunter Source: The Art Bulletin, March 2015, Vol. 97, No. 1 (March 2015), Pp. 58-76 Published By: CAADocumento20 páginasJoshua Reynolds's "Nice Chymistry": Action and Accident in The 1770s Author(s) : Matthew C. Hunter Source: The Art Bulletin, March 2015, Vol. 97, No. 1 (March 2015), Pp. 58-76 Published By: CAATherenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Master Drawings - The Woodner Collection (Art Ebook) PDFDocumento308 páginasMaster Drawings - The Woodner Collection (Art Ebook) PDFvoracious_wolfAún no hay calificaciones

- Pop Art, Op Art, Minimalism, and ConceptualismDocumento40 páginasPop Art, Op Art, Minimalism, and ConceptualismNatnael BahruAún no hay calificaciones

- 02 - Intervencija Crtezom U Interijeru - Walter de MariaDocumento5 páginas02 - Intervencija Crtezom U Interijeru - Walter de MariaKristijan VrdoljakAún no hay calificaciones

- Prints and Visual C 009941 MBPDocumento302 páginasPrints and Visual C 009941 MBPnaluahAún no hay calificaciones

- Art Content Knowledge II Praxis Exam: Collection of QuestionsDocumento21 páginasArt Content Knowledge II Praxis Exam: Collection of Questionsmaisangel100% (8)

- Museum VisitDocumento10 páginasMuseum Visitapi-252383460Aún no hay calificaciones

- Curator's Picks - Cézanne at London's Tate Modern - Financial TimesDocumento30 páginasCurator's Picks - Cézanne at London's Tate Modern - Financial TimesAleksandar SpasojevicAún no hay calificaciones

- Gagosian Gallery - May 2023Documento16 páginasGagosian Gallery - May 2023ArtdataAún no hay calificaciones

- Moma Catalogue 2985 300190099Documento17 páginasMoma Catalogue 2985 300190099Marisol ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- An Exhibition of Chinese Tapestries An Exhibition of Chinese TapestriesDocumento5 páginasAn Exhibition of Chinese Tapestries An Exhibition of Chinese TapestriesVashishta VashuAún no hay calificaciones

- Art May 2013Documento33 páginasArt May 2013ArtdataAún no hay calificaciones

- The Burlington Magazine Publications LTDDocumento10 páginasThe Burlington Magazine Publications LTDTalita LopesAún no hay calificaciones

- Art in America, October, 2001: America The Transient - Jane DicksonDocumento4 páginasArt in America, October, 2001: America The Transient - Jane DicksonalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- The Picasso Papers (Rosalind E. Krauss)Documento142 páginasThe Picasso Papers (Rosalind E. Krauss)ggrazzianoAún no hay calificaciones

- Deconstructing Ode to JoyDocumento6 páginasDeconstructing Ode to JoySara Alonso GómezAún no hay calificaciones

- Rachel Whiteread's 'House'. LondonDocumento3 páginasRachel Whiteread's 'House'. LondonchnnnnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cat 147 NDocumento57 páginasCat 147 NFernanda_Pitta_5021100% (1)

- Franziska Windisch - Walk With A WireDocumento13 páginasFranziska Windisch - Walk With A WireArtdataAún no hay calificaciones

- Softsculptureevents - MEKE SKULPTURE VAOOO PDFDocumento28 páginasSoftsculptureevents - MEKE SKULPTURE VAOOO PDFadinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Early Polychrome Chests From Hadley, MassachusettsDocumento20 páginasEarly Polychrome Chests From Hadley, MassachusettsCristi CostinAún no hay calificaciones

- The Fascination of The UnfinishedDocumento6 páginasThe Fascination of The UnfinishedHaalumAún no hay calificaciones

- Roberta Smith On Robert RymanDocumento6 páginasRoberta Smith On Robert RymanŽeljkaAún no hay calificaciones

- Inmemory00duch PDFDocumento28 páginasInmemory00duch PDFilaughedAún no hay calificaciones

- Taschen Magazine 2004-02Documento92 páginasTaschen Magazine 2004-02jferreira40% (15)

- Pop in The AgeDocumento15 páginasPop in The AgeAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Burden of History - HaydenDocumento25 páginasThe Burden of History - HaydenAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Fabricas de Identidad (Retóricas Del Autorretrato)Documento6 páginasFabricas de Identidad (Retóricas Del Autorretrato)Izei Azkue AstorkizaAún no hay calificaciones

- Oldenburg CatalogueDocumento247 páginasOldenburg CatalogueantonellaAún no hay calificaciones

- Documenta 7Documento24 páginasDocumenta 7Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- 43188773Documento4 páginas43188773Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Whitney 1993Documento7 páginasWhitney 1993Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Conterexhibitions 1850Documento16 páginasConterexhibitions 1850Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.)Documento97 páginasMuseum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.)Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- 781176964relacio ContentDocumento19 páginas781176964relacio ContentAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- 43188773Documento4 páginas43188773Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Arabic Philosophy PDFDocumento10 páginasArabic Philosophy PDFAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Museum of Dissensus PDFDocumento76 páginasThe Museum of Dissensus PDFAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Short CenturyDocumento7 páginasShort CenturyAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Terry Smith - Contemporary ArtDocumento19 páginasTerry Smith - Contemporary ArtAngelica Gonzalez100% (3)

- 43188773Documento4 páginas43188773Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Moma Catalogue Information PDFDocumento215 páginasMoma Catalogue Information PDFAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Hayden White - Historiography and HistoriophotyDocumento8 páginasHayden White - Historiography and HistoriophotyAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Dematerialization and Politicization ofDocumento31 páginasDematerialization and Politicization ofAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Museum of Dissensus PDFDocumento76 páginasThe Museum of Dissensus PDFAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Moma Press-Release 326691Documento2 páginasMoma Press-Release 326691Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Moma Press-Release 326692Documento35 páginasMoma Press-Release 326692Angelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Moma - Master Checklis InformationDocumento20 páginasMoma - Master Checklis InformationAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Issue 14 Ecosystem of ExhibitionsDocumento43 páginasIssue 14 Ecosystem of ExhibitionsAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Deleuze and Contemporary Art PDFDocumento337 páginasDeleuze and Contemporary Art PDFIolanda Anastasiei100% (2)

- Conceptual Art - Benjamin Buchloh - OctoberDocumento40 páginasConceptual Art - Benjamin Buchloh - OctoberAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- The MapDocumento14 páginasThe MapAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Global Art Post-Colonialism and The EndDocumento17 páginasGlobal Art Post-Colonialism and The EndAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- MomaDocumento123 páginasMomaAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Texte Zur KunstDocumento12 páginasTexte Zur KunstAngelica GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Performance ArtDocumento11 páginasPerformance ArtNabiilah Ardini Fauziyyah100% (1)

- Propositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DaysDocumento14 páginasPropositions For A Decolonial Aesthetics and Five Days of Decolonial DayspedrooyeAún no hay calificaciones

- Dissociation + RadioheadDocumento15 páginasDissociation + RadioheadFennelstratocasterAún no hay calificaciones

- IntachDocumento11 páginasIntachAbhishek JaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Endangered Species All GradesDocumento2 páginasEndangered Species All Gradesapi-303422685Aún no hay calificaciones

- By: Deepak Kumar Singh Saumya Kohli Sushant School of Art and ArchitectureDocumento32 páginasBy: Deepak Kumar Singh Saumya Kohli Sushant School of Art and ArchitecturedivugoelAún no hay calificaciones

- Ant and BreadDocumento16 páginasAnt and BreadGenevieve CalvendraAún no hay calificaciones

- Instructional Module (G8)Documento39 páginasInstructional Module (G8)Jesselyn Cristo TablizoAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Write CalligraphyDocumento7 páginasHow To Write Calligraphyjqg5196100% (2)

- The Army Painter Mixing GuideDocumento2 páginasThe Army Painter Mixing Guidepink_golem100% (1)

- Great Wall Walking Tour GuideDocumento83 páginasGreat Wall Walking Tour GuideJudy Baca50% (2)

- The Renaissance and ReformationDocumento3 páginasThe Renaissance and ReformationFrances Gallano Guzman AplanAún no hay calificaciones

- Liquid Ice 7895Documento4 páginasLiquid Ice 7895Павел АнгеловAún no hay calificaciones

- Manila Tytana Colleges Bsba - Financial Management Art AppreciationDocumento3 páginasManila Tytana Colleges Bsba - Financial Management Art AppreciationViah GorreroAún no hay calificaciones

- Dark Winter Color Palette GuideDocumento3 páginasDark Winter Color Palette Guidesunayhernandez1Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Tibetan FurnitureDocumento5 páginasA Tibetan FurnitureEma StrnadAún no hay calificaciones

- Newburyport Pottery Exhibit Antiques & Auction News November 22, 2019Documento1 páginaNewburyport Pottery Exhibit Antiques & Auction News November 22, 2019Justin W. ThomasAún no hay calificaciones

- Create A Cool Vector Panda Character in IllustratorDocumento26 páginasCreate A Cool Vector Panda Character in Illustratorsahand100% (1)

- Carto ConventionsDocumento9 páginasCarto Conventionsjulieta_cortazarAún no hay calificaciones

- Bow in MapehDocumento46 páginasBow in MapehFay BaysaAún no hay calificaciones

- Build Up Rate Format - PaintingDocumento2 páginasBuild Up Rate Format - PaintingFaiz Ahmad80% (10)

- On Course A1+ CLIL Worksheets. 2nd TermDocumento9 páginasOn Course A1+ CLIL Worksheets. 2nd TermNat cgAún no hay calificaciones

- Boq For RCDocumento9 páginasBoq For RCamanAún no hay calificaciones

- Canvas TrousesDocumento5 páginasCanvas TrousesBembis Bemauskas100% (1)

- Senior High School Department S.Y. 2021-2022 1st SemesterDocumento18 páginasSenior High School Department S.Y. 2021-2022 1st SemesterChristy ParinasanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Square and Compasses Volume 1 – Exploring the Origins of FreemasonryDocumento103 páginasThe Square and Compasses Volume 1 – Exploring the Origins of FreemasonryКонстантин Соколов100% (3)

- Nail PolishDocumento8 páginasNail PolishmuneebAún no hay calificaciones

- Eng 103 Midterm ReviewerDocumento11 páginasEng 103 Midterm ReviewerBeyoncé GalvezAún no hay calificaciones

- Study On Malayalam Script PDFDocumento68 páginasStudy On Malayalam Script PDFSAIBINAún no hay calificaciones

- Still Life Drawing TechniquesDocumento8 páginasStill Life Drawing Techniquesabuka.felixAún no hay calificaciones