Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

COOK (2013) Aspect. Pre-Modern Hebrew

Cargado por

jpfvieiraDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

COOK (2013) Aspect. Pre-Modern Hebrew

Cargado por

jpfvieiraCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

HEBREW LANGUAGE

AND LINGUISTICS

Volume 1

AF

General Editor

Geoffrey Khan

Associate Editors

Shmuel Bolokzy

Steven E. Fassberg

Gary A. Rendsburg

Aaron D. Rubin

Ora R. Schwarzwald

Tamar Zewi

LEIDEN BOSTON

2013

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

Table of Contents

Volume One

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ vii

List of Contributors ............................................................................................................ ix

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... xiii

Articles A-F ......................................................................................................................... 1

Volume Two

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Articles G-O ........................................................................................................................ 1

Volume Three

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Articles P-Z ......................................................................................................................... 1

Volume Four

Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii

Index ................................................................................................................................... 1

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

aspect: pre-modern hebrew 201

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

Hebrew-Aramaic reads from right to left, if we

join the dots of the seghol pattern and allow

our voice to follow the pattern, we will begin at

the dot at the base of the pyramid, then rise to

the dot at the apex of the pyramid, and nally

descend toward the dot at the left base of the

pyramid, thus producing a rise-fall pattern.

3 1 Once again, it seems that the intonation

found in modern Yiddish can be traced to chant

patterns that originated in the Land of Israel.

3. L i n k t o t he An c i e n t L a n d of

I s r a e l a n d t o Mode r n I s r a e l

Kahan Newman conjectures that the Jews of

Ashkenaz, remnants of a Palestinian commu-

nity, settled in Ashkenaz before the Babylonian

Talmud became dominant. When, at a later

date, the Babylonian Talmud gained ascen-

dancy, the Jews of Ashkenaz kept the chant

patterns they had used for the Jerusalem Tal-

mud, even as they switched to the Babylonian

Talmud.

Other scholars have postulated a link between

the Land of Israel and the settlers of early Ash-

kenaz, as well. They have noted that in early

Ashkenaz, as in the Land of Israel, extraordi-

nary weight was placed on custom over law

(Ta-Shma 1992:6064, 75). In addition, the

piyyu of early Ashkenaz has been indisput-

ably linked to the piyyu of the Land of Israel

(Ta-Shma 1992:99). The phonology of Yiddish

has been said to derive from the Land of Israel

(Katz 1986:3536), and researchers who study

reading tradition have claimed that the genetic

link of the pre-Ashkenazic tradition with the

(non-Tiberian) Land of Israel tradition is a

proven fact (Ta-Shma 1992:100, n.152).

The intonation patterns discussed here not

only originated in the Land of Israel, but

they have also returned to the modern Israel.

Wherever Ashkenazic Jews have gone, they

have taken these intonation patterns with them.

Modern Israeli Hebrew has adopted these into-

nation patterns from Yiddish, as it has adopted

morphological patterns and patterns of syntax.

The texts and the context have changed, but the

old melody lingers.

Re f e r e n c e s

Grossman, Avraham. 1981. axme Akenaz

ha-rionim. Jerusalem: Magnes.

Heilman, Samuel C. 1981. Sounds of modern ortho-

doxy: The language of Talmud study. Never say

die! A thousand years of Yiddish in Jewish life and

letters, ed. by Joshua A. Fishman, 227253. The

Hague: Mouton.

. 1983. The people of the book. Chicago: Chi-

cago University Press.

Kahan Newman, Zelda. 1995. The inuence of

Talmudic chant on Yiddish intonation patterns.

Yiddish 10:2533.

. 2000. The Jewish sound of speech: Talmu-

dic chant, Yiddish intonation and the Origins

of Early Ashkenaz. Jewish Quarterly Review

90:293336.

Katz, Dovid. 1986. Ha-yesod ha-emi be-Yidi.

Ha-sifrut 3536:228251.

Shpiegel, Mira. 1991. Ha-amira ha-zimratit el

ha-Mina ve-ha-Talmud: Al keriot mi-mesorote-

hem el Yehude Bavel, Qurdisan ve-Akenaz.

MA Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Ta-Shma, Yisrael. 1992. Minhag Akenz ha-qad-

mon. Jerusalem: Magnes.

Weinreich, Uriel. 1956. Notes on the Yiddish rise-

fall intonation contour. For Roman Jakobson:

Essays on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday, ed.

by Morris Halle, Hugh McLean, and Horace Lunt,

633643, The Hague: Mouton.

Wolberger, Arie L. 1991. The music of holy argu-

ment: The ethnomusicology of talmudic debate.

PhD dissertation, Wesleyan University.

Yeivin, Israel. 1960. Hatamat tora e-be-al pe

bi-amim. Lonnu 24:4769, 167178, 207

231.

Zelda Kahan Newman

(Lehman College, City University of New York)

Aspect: Pre-Modern Hebrew

Aspect refers to the internal temporality of

a situation (internal temporal constituency

[Comrie 1976:3]), in contrast to tense, which

refers to a situations external temporality (i.e.,

the temporal location of an event). There are

three distinct categories of aspect:

(A) Situation aspect classies situations by

inherent temporal properties, which accord-

ing to the standard taxonomy include

states, acti-vities, accomplishments, and

achievements.

(B) Phasal aspect, whose types include incep-

tive, resumptive, repetitive, and completive,

treats alterations of a situations internal

temporality, focusing on the beginning,

middle, or end phase of a situation. Situ-

ation and phasal aspect at times have been

conated and the label Aktionsart applied

to one or the other or both types ( Action-

ality [Aktionsart]: Pre-Modern Hebrew).

(C) Viewpoint aspect refers to how a speaker

may choose to view or portray the internal

202 aspect: pre-modern hebrew

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

temporality of a situation. Relevant to

Hebrew are the perfective-imperfective

opposition as well as the perfect (anterior)

and the progressive viewpoint aspects, dis-

cussed in turn below.

1. Vi e wp oi n t As p e c t i n He b r e w

S t u di e s

Aspect is a relatively recently established cat-

egory of linguistic description. The term itself is

a loan translation from Slavic grammar, where

it refers to the perfective-imperfective morpho-

logical distinction (see Binnick 1991:135136).

In Hebrew studies, the Latin terms perfectum

and imperfectum were applied in their etymo-

logical sense of complete and incomplete in

the early 19th century (McFall [1982:44] traces

the introduction of the terms to Johann Jahns

1809 Grammaticae linguae Hebraeae). Hein-

rich Ewald (1879) popularized these terms in

his widely read Hebrew and Arabic grammars

and established the aspectual theory of the

Hebrew verbal system as the major alternative

to the medieval description of the Hebrew verb

forms in terms of tense (e.g., Elias Levitas 1518,

cited in McFall 1982:12). Despite differences

between Ewalds theory and Drivers (1998)

treatment of the Hebrew verb, the latters work

served to disseminate the basic aspectual the-

ory particularly in English-speaking scholarship

(see esp. Driver 1998:xiiilxxxvi).

In the 20th century numerous studies were

published in which the Hebrew verbal con-

jugations were described in terms of tense,

aspect, or (more recently) mood oppositions,

but no consensus was reached beyond the

long-standing tense explanation (e.g., Joon

and Muraoka 2006:326327) and the aspect

theory (e.g., GKC 309, 313) found in the stan-

dard grammars. For a survey of the eld, see

Cook (2002:chap. 2). The disparate approaches

reect the problems inherent in describing lin-

guistic structure in terms of abstract catego-

ries such as tense, aspect, or mood. For this

reason many linguists have eschewed such an

approach, choosing to focus on tense-aspect-

mood (TAM) as an undifferentiated whole,

and treating individual conjugations without

classifying them within one of these abstract

categories (e.g., Lindstedt 2001:770). While it

is true that the individual conjugations, which

generally express a cluster of TAM meanings

(e.g., perfective conjugations frequently express

past tense, future tense also expresses volitive

mood), are the real building blocks of TAM

systems, the abstract categories of tense, aspect,

and mood retain their usefulness for the pur-

poses of typological comparison. For example,

the presence of a distinct class of stative verbs

in Biblical Hebrew ( Actionality [Aktionsart]:

Pre-Modern Hebrew) and absence of tense

shifting (as for example English indicative I am

rich versus conditional If I were rich) both

align the Biblical Hebrew verbal system with

aspect-prominent TAM systems (Bhat 1999:40,

150). The following treats the grammatical

types which belong to the category of viewpoint

aspect and discusses how these are expressed in

the Hebrew verbal system in the pre-modern

period.

2. A B a s i c T a x on omy of

Vi e wp oi n t As p e c t

There are four basic viewpoint aspects relevant

to the description of Hebrew: perfective, imper-

fective, perfect, and progressive. These may be

dened in terms of the relationship between

an event frame and a reference frame. The

event frame is the time interval during which a

situation holds true; the reference frame is the

time span for which a speaker chooses to view

(portray) a situation. A helpful metaphor of

the relationships that may hold between event

and reference frames is that between different

types of camera lenses and the subject: the

perfective viewpoint is like a wide-angle lens,

which includes the end points of a situation but

at the expense of a detailed view of its internal

temporal structure; the imperfective viewpoint

is like a telephoto lens, which excludes the

end points of a situation because of its nar-

row scope but provides a detailed view of the

situations internal temporal structure. This

metaphor captures the characteristic temporal

succession of the perfective versus the tempo-

ral overlay of the imperfective, for example

(French) Quand Pierre entra, Marie tlphonait

When Pierre entered Marie was talking on

the phone versus Quand Pierre entra, Marie

tlphona When Pierre entered, Marie made

a phone call (Kamp and Rohrer 1983:253).

Because the imperfective tlphonait portrays

the internal temporal structure of the situation,

the previously-reported event entra is under-

aspect: pre-modern hebrew 203

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

The perfective/past conjugation in Hebrew can

be identied at every stage along this path,

beginning with its precursor in a West Semitic

resultative construction consisting of an adjecti-

val form and a subject pronoun: qarib + ( at)ta

you (are) drawn near. In the earliest stages of

Hebrew this conjugation developed beyond the

resultative to express both perfect and perfec-

tive aspects, presumably reecting the retention

of the former even after the latter came into

being (e.g., qrat you have drawn

near~you drew near).

Syntactic and discourse factors help distin-

guish between these two aspectual senses in

Biblical Hebrew, particularly in narrative dis-

course where perfective aspect is predominantly

expressed by the past narrative verb. Interrup-

tions of a string of past narrative forms by a

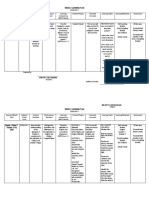

Figure 1. Grammaticalization paths for perfective/simple past verbs (adapted from Bybee,

Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994:105).

resultative (be/ have)

completive (nish)

\

/

perfect perfective/simple past

stood to overlay or interrupt the latter. By

contrast, if both situations are portrayed with

the perfective, they are understood to occur in

succession.

The classication of the perfect viewpoint

aspect has been debated because of its unique

features (see Comrie 1976:52). For one, the

perfect allows for tense distinctions in some

languages (e.g., English had run, has run, will

have run). For this reason relative tense theory

has been able to treat the perfect as a tense

form (Reichenbach 1947:297). At the same

time, the perfect may also combine with the

progressive viewpoint aspect (e.g., English had

been running). By making a distinction between

a situations nucleus and coda (to borrow

terms from syllable phonology), the perfect

can be dened in terms of the event frame and

reference frame relationship: the perfect has a

perfective-like scope, which includes the end

points of an interval of a situation; but this is

an interval of the codathe resultant state of

the preceding nucleus of the situationwhich

is included in the scope, and not an interval of

the nucleus, as the perfective scope includes.

This sort of analysis explains the characteristic

current relevance of perfect expressions: the

perfect conveys that a current state of affairs

(the event coda) is semantically or logically

the result of a preceding situation (the event

nucleus).

The progressive has been likewise variously

treated (see Binnick 1991:281290). Most

importantly, it cannot be distinguished from

the imperfective using the event and reference

frame model. However, there are a number of

cross-linguistic tendencies that distinguish the

two viewpoints. First, progressives often are or

develop from periphrastic constructions, and/

or are based on nominal forms (Dahl 1985:91;

Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994:130).

Second, progressives are more restricted than

imperfectives: they generally do not occur with

stative predicates, and they generally have a

narrower future time use, either expressing an

expected event (Comrie 1976:3334; Bybee,

Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994:249250) or an ele-

ment of intention (Binnick 1991:289). Third,

the perfective/imperfective opposition is often

correlated with the tensed past/non-past oppo-

sition, whereas the progressive is freely used for

past, present, and future time reference (Dahl

1985:9293). Hence, although the imperfective

and progressive are semantically indistinguish-

able, they can be differentiated based on consis-

tent cross-linguistic characteristics.

3. E x p r e s s i on of P e r f e c t a n d

P e r f e c t i v e Vi e wp oi n t s i n

He b r e w

In order to describe the expression of view-

point aspects over the course of the history of

Hebrew it is helpful to employ a framework

of typical paths of development involving the

relevant viewpoints. One of these is the devel-

opment path in gure 1, involving the perfect

and perfective viewpoints.

204 aspect: pre-modern hebrew

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

perfective/past verb often indicate a perfect

meaning of the latter (Zevit 1998). For exam-

ple,

YHWH (lhm hirb

<

m w-

hinnm hay-ym k- ha-

<

mayim l

<

-

r Yhwh your God has multiplied you; and,

look, today you (are) as the stars in heaven with

regard to (your) numerousness (Deut. 1.10);

way-yihall n -h

<

-(lhm w-nnn

k-l

<

qa (lhm And Enoch walked with

God, and (then) he was not, because God had

taken him (Gen. 5.24);

w-h k-m

<

-ql ha-

<

<

b-r

<

hab-b

<

m

<

z t

am-mil

<

m

<

k-y

<

<

h

<

-(lhm l-

<

n

<

lhakk -man litm And when you

hear the sound of marching in the tops of the

mulberry trees, then you shall go forth into

battle, for God will have gone forth before you

to strike the camp of the Philistines (1 Chron.

14.15). However, in non-literary epigraphic

texts and in non-narrative portions of the Bible

the perfective/past form regularly expresses per-

fective (past) situations. For example,

b-rn

m

<

la al-yh

<

a

<

nm w-i

<

<

m

--r

<

layim m

<

la lm w-

<

l

<

n

<

al kl-yir

<

l w-h

<

In Hebron he [David]

reigned over Judah seven years and six months,

and in Jerusalem he reigned thirty-three years

over all Israel and Judah (2 Sam. 5.5).

Since the past narrative form (wayyiqol)

went out of use in post-biblical Hebrew, the

perfective/past conjugation assumed the for-

mers functions. Thus in narrative contexts

the tense characteristics of the perfective/past

are highlighted (past tense being the default

temporal interpretation of perfective verbs

[Smith 2008]). However, the conjugation could

still express perfect aspect, distinguished from

perfective-past by the general context. For

example, the following present performative

verb ( hiarti I take responsibility)

determines the perfect interpretation of

ati I have taken upon myself in the follow-

ing example: ,

kol e-ati bi-mirato, hiarti et nizqo For

everything that I have taken it upon myself to

look after, I take responsibility for any damage

(Mishna Bava Qama 1.2; translation Perez-

Fernandez 1992:117).

The lost present state interpretation of the

perfective/past verb with stative predicates in

the Mishna is an important indicator of this

forms shift towards becoming a past tense,

since the interaction with statives is an impor-

tant distinguishing feature between perfective

and past verbs (Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca

1994:9192).

4. E x p r e s s i on of I mp e r f e c t i v e

a n d P r og r e s s i v e

The progressive and imperfective aspects are

not only semantically similar, but also develop-

mentally related: progressive constructions are

a regular source of imperfective verbs (Bybee,

Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994:127129). It is

therefore not surprising that the imperfective/

future conjugation and the predicative partici-

ple overlap in meaning and function in Biblical

Hebrew. For example, compare the following:

way-yi

<

lh h

<

- lmr ma-ttaqq.

way-ymr -aay

<

n maqq And

the man asked him, What are you searching

(imperfective/future) for? And he said, I (am)

searching (participle) for my brothers (Gen.

37.15b16a).

However, the shift of the Hebrew TAM sys-

tem from aspect to tense prominence (Stassen

1997:495499; Heine 2005:294) already in

Biblical Hebrew has made the predicative par-

ticiple the preferred means for the expression

of progressive situations in past time, though

some past progressive imperfective/future forms

still appear.

The above-described shift, along with the

imperfective/futures appropriation of the voli-

tive functions of the jussive and cohortative

forms in the post-biblical period, led to a

restriction of the imperfective/future form in

indicative clauses. The progressive-aspect parti-

ciple became the preferred indicative form not

only for progressive and habitual situations,

but also for vivid past narration and expected

future events (see Prez Fernndez 1992:134

138). Compared to Biblical Hebrew, however,

there is an increased use of periphrastic con-

structions (using the perfective/past copular

form) for tense distinctions with the progressive

aspect: modern hebrew 205

2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3

participle: ,

e-haya mitpallel al ha-olim we-omer, ze

ay we-ze met When he was praying for the

sick he would say, This one is going to live

and this one is going to die. (Mishna Berak-

hot 5.5; see Prez-Fernndez 1992:137).

Re f e r e n c e s

Bhat, Darbhe Narayana Shankara. 1999. The promi-

nence of tense, aspect, and mood. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Binnick, Robert I. 1991. Time and the verb: A guide to

tense and aspect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca.

1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect,

and modality in the languages of the world. Chi-

cago: University of Chicago Press.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Cook, John A. 2002. The Biblical Hebrew verbal

system: A grammaticalization approach. PhD

dissertation, Department of Hebrew and Semitic

studies, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Dahl, sten. 1985. Tense and aspect systems.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Driver, Samuel Rolles. 1998. A treatise on the use of

the tenses in Hebrew and some other syntactical

questions. 3rd edition, reprint, with an introduc-

tory essay by W. Randall Garr. Grand Rapids,

Michigan: Eerdmans (Original edition, 1892).

Ewald, Heinrich. 1879. Syntax of the Hebrew lan-

guage of the Old Testament. Trans. by James Ken-

nedy. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

GKC = Kautzsch, Emil (ed.). 1910. Gesenius Hebrew

grammar. Trans. by Arthur E. Cowley. Oxford:

Clarendon.

Joon, Paul and Takamitsu Muraoka. 2006. A gram-

mar of Biblical Hebrew. Revised English edition.

Rome: Pontical Biblical Institute Press.

Kamp, Hans and Christian Rohrer. 1983. Tense in

texts. Meaning, use, and interpretation of lan-

guage, ed. by Rainer Buerle, Christoph Schwarze,

and Arnim von Stechow, 250269. Berlin: Walter

de Gruyter.

Lindstedt, Jouko. 2001. Tense and aspect. Lan-

guage typology and language universals: An inter-

national handbook, ed. by Martin Haspelmath

et al., 768783. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

McFall, Leslie. 1982. The enigma of the Hebrew

verbal system. Shefeld: Almond.

Prez Fernndez, Miguel. 1997. An introductory

grammar of Rabbinic Hebrew. Trans. by John

Elwolde. Leiden: Brill.

Reichenbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of symbolic

logic. London: Collier-Macmillan.

Smith, Carlota S. 2008. Time with and without

tense. Time and modality, ed. by Jacqueline

Guron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 227250. Dor-

drecht: Springer.

Zevit, Ziony. 1998. The anterior construction in

classical Hebrew. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

John A. Cook

(Asbury Theological Seminary)

Aspect: Modern Hebrew

Like tense, aspect is a category related to the

expression of temporality. Aspect encodes dif-

ferent ways of viewing the internal temporal

constituency of a situation (Comrie 1976:3).

Tense and aspect encode topological rela-

tions between two time intervals. In main,

unembedded contexts, tense relates speech time

(S) to reference time (R), the time which the

statement is about (Reichenbach 1947); tense

is thus a deictic category. Aspect relates event

time (E), the time of the described event/state,

to R; this relation has to do, for instance,

with whether the boundaries of the event are

included in the reference time or not. Referring

to the boundaries of the event time is only one

facet of what is commonly covered by aspect.

This temporal relation has been dubbed gram-

matical aspect or viewpoint aspect (Smith

1991; Klein 1994:99119; Demirdache and

Uribe-Extebarria 2000). Other properties hav-

ing to do with the internal temporal structure of

events are (i) whether or not an event involves

change in time, i.e., stative vs. dynamic; (ii)

whether an event holds at a moment or at an

interval, i.e., punctual vs. durative; (iii) whether

an event has built into it a terminal point, or

can be protracted indenitely, i.e., telic vs.

atelic.

These three properties are used to classify

event descriptions into aspectual classes. An

attempt at such a classication dates back to

Aristotles distinction between kinsis and ener-

geia. The aspectual classes commonly featuring

in the literature are states, activities, accom-

plishments, and achievements (Ryle 1949:149

153; Vendler 1957; Kenny 1963; Dowty 1979:

chapter 2). These are referred to as lexical

aspectual classes. Here is an illustration of the

properties making up the classes.

(1)

Dynamic Durative Telic

State

Activity + +

Accomplishment + + +

Achievement + +

También podría gustarte

- Regna and GentesDocumento718 páginasRegna and Genteskalekrtica100% (8)

- VIGLIETTI Servilian Triens ReconsideredDocumento26 páginasVIGLIETTI Servilian Triens ReconsideredjpfvieiraAún no hay calificaciones

- Inscriptional Pahlavi GrammarDocumento173 páginasInscriptional Pahlavi GrammarDavid Noel67% (3)

- IslamDocumento225 páginasIslamfreewakedAún no hay calificaciones

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1091)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Abridged Draft Constitution Summary of Zimbabwe (Kalanga)Documento62 páginasAbridged Draft Constitution Summary of Zimbabwe (Kalanga)Parliamentary Monitoring Trust ZimbabweAún no hay calificaciones

- Plinth To ParamountDocumento424 páginasPlinth To Paramountkmanas153100% (1)

- IcebreakersDocumento3 páginasIcebreakersRandy RebmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Comparative and Superlatives: Professional English IiDocumento36 páginasComparative and Superlatives: Professional English IiZander Meza ChoqueAún no hay calificaciones

- Links in DiscourseDocumento14 páginasLinks in Discoursehossin karimiAún no hay calificaciones

- 0510 English As A Second Language: MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersDocumento10 páginas0510 English As A Second Language: MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersIbrahim LubabAún no hay calificaciones

- English Exercises - WAS-WASN't-WERE-WEREN'TDocumento2 páginasEnglish Exercises - WAS-WASN't-WERE-WEREN'TDaniella Alejandra ArevaloAún no hay calificaciones

- First Conditional - Grammar Chart: If Clause and Main ClauseDocumento4 páginasFirst Conditional - Grammar Chart: If Clause and Main Clauseandres contrerasAún no hay calificaciones

- 16th Century PoetryDocumento37 páginas16th Century PoetryHarzhin AzizAún no hay calificaciones

- IPA ChartDocumento4 páginasIPA ChartCrystal LeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter Vii: Communication For Academic PurposesDocumento10 páginasChapter Vii: Communication For Academic PurposesEllen Grace Baguilat PutacAún no hay calificaciones

- Transformational - Generative GrammarDocumento56 páginasTransformational - Generative GrammarHocon8682Aún no hay calificaciones

- Weekly Learning Plan EnglishDocumento6 páginasWeekly Learning Plan EnglishEvelyn DEL ROSARIOAún no hay calificaciones

- The Ing FormsDocumento3 páginasThe Ing FormsYostin Zamir Palacios MenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Anglosaxonreader00swee BW PDFDocumento420 páginasAnglosaxonreader00swee BW PDFcorvinAún no hay calificaciones

- B1 Grammar - On The Road BookletDocumento32 páginasB1 Grammar - On The Road BookletMustafa MhommedAún no hay calificaciones

- Lichtenberk, Frantisek - Multiple Uses of Reciprocal ConstructionsDocumento25 páginasLichtenberk, Frantisek - Multiple Uses of Reciprocal ConstructionsMaxwell MirandaAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Arabic Type EvolutionDocumento41 páginasHistory of Arabic Type Evolutionwooshy100% (1)

- Olympiad English Pronouns Worksheet Grade 5Documento2 páginasOlympiad English Pronouns Worksheet Grade 5SuvashreePradhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Carolyn D. Rude - Technical Editing-Pearson, Longman (2006)Documento489 páginasCarolyn D. Rude - Technical Editing-Pearson, Longman (2006)Javier FernándezAún no hay calificaciones

- AssignmentDocumento4 páginasAssignmentEsha KulsoomAún no hay calificaciones

- SK Kuala Mai Bharu: 28050 Kuala Krau Pahang Darul MakmurDocumento10 páginasSK Kuala Mai Bharu: 28050 Kuala Krau Pahang Darul MakmurSyakilla TaibAún no hay calificaciones

- The Functions of Context in Discourse Analysis: International Journal of Linguistics Literature and Culture August 2022Documento12 páginasThe Functions of Context in Discourse Analysis: International Journal of Linguistics Literature and Culture August 2022Rika Erlina FAún no hay calificaciones

- CORE Class Grade 2-3 (Phonics Survey)Documento1 páginaCORE Class Grade 2-3 (Phonics Survey)Chatty DoradoAún no hay calificaciones

- MR 2018 5 e 9 BorszekiDocumento38 páginasMR 2018 5 e 9 BorszekiborszekijAún no hay calificaciones

- Unit Plan MaterialsDocumento20 páginasUnit Plan Materialsapi-2201098980% (1)

- Book SudhaDocumento62 páginasBook SudhaNavi AchariyaAún no hay calificaciones

- (Hướng dẫn chấm này gồm 02 trang)Documento2 páginas(Hướng dẫn chấm này gồm 02 trang)Nguyen Hoang LanAún no hay calificaciones

- HDE Placement Test - 2020Documento14 páginasHDE Placement Test - 2020AriadnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Professional English IIDocumento4 páginasProfessional English IIDeepanAún no hay calificaciones