Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Informe Cecchini. Sobre Los Costes de La No-Europa

Cargado por

Nicky SantoroTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Informe Cecchini. Sobre Los Costes de La No-Europa

Cargado por

Nicky SantoroCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

)

r

~

RESEARCH ON THE "COST OF NON-EUROPE"

BASIC FINDINGS

VOLUME 5 PART B

I B --------

- ~ --

---

--

- ----

- - -====-- = ~ =

THE "COST OF NON-EUROPE"

***

* *

* *

* *

***

IN PUBLIC-SECTOR PROCUREMENT

Document

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES

This publication was prepared outside the Commission of the European Communities.

The opinions expressed in it are those of the author alone; in no circumstances should

they be taken as an authoritative statement of the views of the Commission.

Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication.

Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1988

ISBN 92-825-8647-2

Part A + Part B: ISBN 92-825-8648-0

Catalogue number: CB-P2-88-F14-EN-C

ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels Luxembourg, 1988

Printed in the FR of Germany

RESEARCH ON THE "COST OF NON-EUROPE"

BASIC FINDINGS

VOLUME 5 PART B

EUROPE"

***

* *

* *

* *

***

IN PUBLIC-.SECTOR PROCUREMENT

BELEGEXEMPLAR - 0\ESE VEROFFENTUCHUNG

iST ERSCH\ENEN UND W\RD VfJN7AMT

, GEN vtR'fRtEBEN

FOR VERbFFENTLtCHUN

WS Atkins Management Consultants

<\NTirPA0

E urequipu,6AuRolana Partner-Eurequip It alia

. - ED BY THE OFFICE

SPEC\iv\EN u::,Y -,:_USH

r .=>'U'' \rATIONS

FOR ur-r-1 - ' .J- -

EXEMPLAiRE TEMOlN DE MISE EN VENTE

PAR L'OFf\CE DES ;::>UBLICATIONS

ESEMPLARE MES90 IN VENDlTA OALL'UPFlCto

DELLE pUBBLICAZ\ONI

ooP

DOOR t<15t

BEWIJSEXEMPLAAR VAN

Document

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES

This publication was prepared outside the Commission of the European Communities.

The opinions expressed in it are those of the author alone; in no circumstances should

they be taken as an authoritative statement of the views of the Commission.

ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels - Luxembourg, 1988

Printed in the FR of Germany

- SS'i -

THE COST OF NON-EUROPE IN PUBLIC SECTOR PROCUREMENT

PART I I REPORT

WS ATKINS MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS

Woodcote Grove Ashley Road

Epsom Surrey KT18 5BW

10524.01

10/36:87

- 555 -

CONTENTS

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY- see part A

2. IDENTIFICATION OF IMPORTANT SECTORS AND PRODUCTS

2.1 Product Reviews

2.2 The Price Effect List

2.3 The Restructuring List

2.4 Selection of Products for Analysis

3. PRICE COMPARISONS

Page

42

42

42

48

52

55

3.1 Objectives and Methodology 55

3.2 Practical Problems of Price Comparison 56

3.3 Data Sources 59

3.4 Comparison of Prices - General Comments 62

3.5 Savings Thresholds and Calculation of Savings

Factors 66

3.6 Comment on Products in Direct Price Enquiries 68

.. 55f> -

4. CASE STUDY 1: COAL

5.

6.

7.

4.1 Industry Structure

4.2 Competitiveness

4.3 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

4.4 Scenario

CASE STUDY 2: HEAVY FABRICATIONS (BOILERS AND PRESSURE

VESSELS)

5. 1 Industry Structure

5.2 Competitiveness

5.3 Economies of Scale

5.4 Effect of Opening Up Public Procurement

5.5 Scenario

CASE STUDY 3: TURBINE GENERATORS

6. 1 Industry Structure

6.2 Competitiveness

6.3 Economies of Scale

6.4 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

6.5 Scenario

CASE STUDY 4: ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVES

7. 1 Industry Structure

7.2 Competitiveness

7.3 Economies of Scale

7.4 The Effect of Opening Up Public Procurement

7.5 Scenario

Page

90

90

90

92

93

95

95

100

100

102

105

107

107

110

113

116

117

119

119

124

125

127

129

- 557 -

8. CASE STUDY 5: MAINFRAME COMPUTERS

8.1 Industry Structure

8.2 Competitiveness

8.3 Economies of Scale

8.4 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

8.5 Scenario

9. CASE STUDY 6: SWITCHING EQUIPMENT

9.1 Industry Structure

9.2 Competitiveness

9.3 Economies of Scale

9.4 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

9.5 Scenario

10. CASE STUDY 7: TELEPHONE HANDSETS

10.1 Industry Structure

10.2 Competitiveness

10.3 Economies of Scale

10.4 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

10.5 Scenario

11. CASE STUDY 8: LASERS

11.1 Industry Structure

11.2 Competitiveness

11.3 Economies of Scale

11.4 Effects of Opening Up Public Procurement

11.5 Scenario

Page

130

130

133

135

135

137

139

139

145

147

151

152

153

153

155

156

157

158

160

160

163

163

164

165

- SSR -

Page

12. POTENTIAL SAVINGS IN PUBLIC EXPENDITURE 166

12.1 Introduction 166

12.2 Formulae Used in the Model 167

12. 3 Data Used 169

12.4 Hypothesis on the Change in Import Penetration 173

12.5 Base Case Calculations 181

12.6 Sensitivity Analysis 185

12.7 Caveats 187

12.8 Unquantified Effects 189

APPENDICES

I SPECIFICATION OF PRICE EFFECT LISP SAMPLE PRODUCTS

II CALCULATION OF TYPICAL SAVINGS THRESHOLDS AND

POTENTIAL SAVINGS

III THE CASE STUDY INDUSTRIES IN THE USA

IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

V BIBLIOGRAPHY

192

198

238

276

279

- 559 -

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - see part A

Page

Tables

Table 2. 1 Evaluation of Products for Potential Benefits from

the Internal Market 43

Table 2.2 The Price Effect List 49

Table 2.3 The Restructuring List 50

Table 3.1 Average Prices of 'Eurostat' Standard Goods 1986 61

Table 3.2 Price of Sample Products to Public Sector Purchasers

(from direct enquiries) 63

Table 3.3 Potential Static ~ r i e Savings by Product 69

Table 3.4 Potential Price Savings for Digoxin 74

Table 3.5 Potential Price Savings for BEUC Basket of

Pharmaceuticals 74

Table 3.6 Potential Price Savings for Power Cables 76

Table 3.7 Potential Price Savings for Street Lamps 77

Table 3.8 Potential Price Savings for Fluorescent Tubes 78

Table 3.9 Potentia 1 Price Savings for School Desks 79

Table 3.10 Potential Price Savings for Office Desks 80

Table 3.11 Potential Price Savings for Filing Cabinets 80

- 560 -

Table 3.12

Table 3.13

Table 3. 14

Table 3.15

Table 3.16

Table 3.17

Table 3.18

Table 3.19

Table 3.20

Table 3. 21

Table 3. 22

Table 5. l

Table 5.2

Table 6. l

Table 6.2

Table 6.3

Table 6.4

Table 7 .l

Table 7.2

Table 8. l

Table 8.2

Table 8.3

Potential Price Savings for Uniforms

Potential Price Savings for Copier Paper

Potential Price Savings for Cement

Potential Price Savings for Opel Ascona

Potential Price Savings for Fiat Ducato

Potential Price Savings for VW Transporter

Potential Price Savings for Cardiac Monitor

Potential Price Savings for X-ray Machine

Potential Price Savings for Transformers

Potential Price Savings for Goods Wagon

Potential Price Savings for Telephones

Cost Structure in Boilers/Pressure Vessels Fabrication

Short Term Economies of Scale in Boilers/Pressure

Vessels

Ranking of Firms by Export Orders 1981-86 for Power

Generation Plant

Ranking of Heavy Electrical Engineering Firms

Cost Breakdown in Turbine Generator Manufacture

Short Run Economies of Scale in Turbine Generator

Manufacture

Page

81

82

82

84

84

85

85

87

88

88

89

l 01

l Ol

lll

112

114

115

Cost Structure of Some Locomotive Manufacturers 126

Short Run Economies of Scale in Locomotive Manufacture 126

Computer Equipment Suppliers to Europe: Market Shares

and Production 1986 131

Manufacturers Shares of the European Mainframe Market 131

Manufacturers Shares of the European Public Sector

Mainframe Market 136

- 561 -

Table 9.1

Table 9.2

Table 9.3

Table 9.4

Table 9.5

Table 9.6

Tab 1 e 10.1

Table 10.2

Tab 1 e 12.1

Table 12.2

Table 12.3

Table 12.4

Table 12.5

Table 12.6

Table 12.7

Table 12.8

Table 12.9

Tab 1 e 12.10

Table 12. 11

Main European CPE Switching Systems

CPE Digital Switches Installed in Belgium, France,

Germany, Italy and the UK (1987)

Public Switches to be Installed in 1987

Recent Mergers, Joint Ventures and Acquisitions in the

European Public Switching Industry

Cost Breakdown in Switch Manufacture

Short Run Economies of Scale in Switch Manufacture

Cost Structure in Telephone Handset Manufacturing

Short Term Economies of Scale in Telephone Handsets

Potential Savings Factors

Breakdown of Public Purchasing by Product Category

Assumed Public Sector Import Penetration Rates

Avera9e Import Penetration n t e ~

Public/Private Sector Intermediate Consumption

Implicit Private Sector Import Penetration

Change in Public Sector Import Penetration after "1992"

Base Case Estimate of the Static Trade Effect

Base Case Estimate of the Competition Effect

Base Case Estimate of the Restructuring Effect

Summary of Base Case Estimates of Total Savings

Table 12.12 Sensitivity Analysis

Table 12.13 Summary of Potential Savings

Tab 1 e I I. 1

Table I I. 2

Table II.3

Table I I. 4

Tab 1 e I I I. 2 . 1

Tab 1 e I I I. 3 . 1

Estimation of Savings Thresholds

Calculation of Potential Savings Factors

Calculation of Potential Savings - Summary

Hermes Model Factors

Comparison of US and EC Boiler Production

US and EC Production of Turbine Generator Sets

Page

140

141

142

148

148

149

156

157

170

172

176

177

178

179

180

182

183

184

185

186

187

204

219

234

235

244

246

- 562 -

Page

Table III.4.1 Comparison of US and EC Locomotive Industry 251

Table III.5.1 US Mainframe Computer Manufacturers 253

Table III.5.2 Comparison of the US and EC Mainframe Computer

Industries 255

Table III.6.1 Supplies of Switches to the USA 1984 257

Table III.6.2 Manufacturers' Sales of Digital Switches 261

Table III.6.3 Production of Digital Switches by Region 262

Table III.6.4 Comparison of Prices for Digital Switches 262

Table III.6.5 Trade Balances in Telecommunications Equipment ( 1984) 264

Table III.7.1 Breakdown of US Telecoms Market by Type of Equipment 266

Table III.7.2 Telephone Operating Revenues by Type of Carrier (USA) 268

III.9.1 EC US T3riff on S@l!rted Products 1987

?7C

-:-

Figures

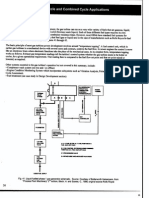

Figure II. 1 A Simple Transport Cost Model

200

- 563 -

42

2. IDENTIFICATION OF IMPORTANT SECTORS AND PRODUCTS

2.1 Product Reviews

The purpose of this Section is to identify those products for which

there might be a significant static price effect (the "price effect

list"), and those industries for which there might be an important

economies of seale or restructuring effect (the "restructuring"

list). The prices of those products on the price effect list, and

the structure, costs and development strategies of industries on the

economies of scale list, are analysed in the following sections of

the Report.

Table 2.1 shows the results of a systematic analysis of supplying

sectors, summarised at the 2 digit NACE code level, but considering

products at the 3 digit level. The table shows two alternative

measures, using the French contract data and the input-output

analysis reported in Section 5.3 and 5.4 of the Part I Report, of:

* the share of the product in total public purchasing

* the importance of the public sector as purchaser of the whole

branch's output.

These data have been used to measure the relative impact of opening

up public purchasing on different product sectors.

2.2 The Price Effect List

The Price Effect List includes products which:

* have a large share in public purchasing, so that price

differences lead to significant savings

N

A

C

E

/

D

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

o

n

0

:

A

G

,

F

I

S

H

,

H

U

N

T

I

N

G

0

1

A

g

r

i

c

u

l

t

u

r

e

a

n

d

h

u

n

t

i

n

g

0

2

F

o

r

e

s

t

r

y

0

3

F

i

s

h

i

n

g

1

:

E

N

E

R

G

Y

A

N

D

W

A

T

E

R

1

1

E

x

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

o

f

s

o

l

i

d

f

u

e

l

s

1

2

C

o

k

e

o

v

e

n

s

1

3

E

x

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

o

f

p

e

t

r

o

l

e

u

m

&

g

a

s

1

4

O

i

l

r

e

f

i

n

i

n

g

1

5

N

u

c

l

e

a

r

f

u

e

l

s

1

6

P

o

w

e

r

g

e

n

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

1

7

W

a

t

e

r

s

u

p

p

l

y

2

:

N

O

N

E

N

E

R

G

Y

M

I

N

E

R

A

L

S

2

1

M

e

t

a

l

l

i

f

e

r

o

u

s

o

r

e

s

2

1

1

f

e

r

r

o

u

s

2

1

2

n

o

n

f

e

r

r

o

u

s

2

2

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

p

r

e

l

i

m

i

n

a

r

y

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

I

-

0

I

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

I

-

0

1

-

0

p

r

o

c

e

s

s

i

n

g

o

f

m

e

t

a

l

s

1

-

0

2

2

1

i

r

o

n

a

n

d

s

t

e

e

l

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

2

2

2

s

t

e

e

1

t

u

b

e

s

F

2

2

3

c

o

l

d

f

o

r

m

i

n

g

o

f

s

t

e

e

l

T

A

B

L

E

2

.

1

-

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

O

F

P

R

O

D

U

C

T

S

F

O

R

P

O

T

E

i

i

T

l

A

L

B

E

N

E

F

I

T

S

F

R

O

M

T

H

E

I

N

T

E

R

N

A

L

M

A

R

K

E

T

I

%

P

P

/

I

I

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

1

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

1

o

f

P

P

o

u

t

p

u

t

I

S

t

a

t

i

c

P

r

i

c

e

A

d

v

a

n

t

a

g

e

I

r

e

j

e

c

t

I

R

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

/

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

S

e

a

l

e

r

e

j

e

c

t

I

0

.

6

0

.

1

3

.

5

2

.

4

0

.

1

0

.

9

8

.

0

1

6

.

8

0

.

3

2

.

2

0

.

4

0

.

3

0

.

6

I

1

.

1

0

.

1

5

3

.

1

3

1

.

3

I

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

b

l

i

c

P

P

=

3

0

%

o

f

o

u

t

p

u

t

i

n

F

r

a

n

c

e

;

p

o

l

i

c

i

e

s

e

x

i

s

t

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

t

i

c

2

.

3

N

o

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

P

P

3

.

0

C

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

w

o

r

l

d

m

a

r

k

e

t

(

a

l

>

o

,

h

i

g

h

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

c

o

s

t

s

f

o

r

n

a

t

u

r

a

l

g

a

s

)

1

6

.

1

H

i

g

h

l

y

c

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

w

o

r

l

d

m

a

r

k

e

t

;

p

r

i

c

e

1

5

.

7

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

f

r

o

m

s

u

p

p

l

i

e

r

s

m

J

r

g

i

n

a

l

.

R

e

t

a

i

l

p

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

a

r

e

d

u

e

t

o

e

x

c

i

s

e

t

a

x

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1

8

.

0

N

o

E

C

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

o

f

o

r

e

s

;

E

C

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

d

o

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

o

w

n

p

r

o

c

e

s

s

i

n

g

f

a

c

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

.

N

o

o

p

e

n

m

a

r

k

e

t

,

s

o

n

o

o

b

s

e

r

v

a

b

l

e

p

r

i

c

e

s

1

1

.

3

S

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

t

r

a

d

e

u

n

r

e

a

l

i

s

t

i

t

1

3

.

2

N

o

t

f

r

e

e

l

y

t

r

a

d

e

a

b

l

e

-

h

i

g

h

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

c

o

s

t

,

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

i

c

a

r

g

u

m

e

n

t

s

E

u

r

o

p

e

a

n

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

m

o

r

e

e

x

p

e

n

s

1

v

e

t

h

a

n

o

t

h

e

r

w

o

r

l

d

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

.

S

o

m

e

P

P

b

y

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

e

d

s

t

e

e

l

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

u

t

m

a

i

n

l

y

o

n

a

c

o

m

m

e

r

c

i

a

l

b

a

s

i

s

.

T

h

e

r

e

i

s

s

o

m

e

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

o

f

n

o

n

-

f

e

r

r

o

u

s

m

i

x

i

n

g

b

u

t

n

o

f

o

r

i

n

t

r

a

-

E

C

t

r

a

d

e

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

0

X

0

0

0

(

X

)

0

0

0

S

t

e

e

l

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

a

r

e

t

r

a

d

e

d

0

1

.

3

c

o

m

m

o

d

i

t

i

e

s

.

S

u

p

p

l

i

e

r

s

a

r

e

t

r

a

d

e

r

s

w

h

o

b

u

y

i

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

l

y

.

E

x

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

s

m

a

y

b

e

s

p

e

c

i

a

l

!

1

.

8

s

t

e

e

l

s

f

o

r

a

r

m

a

m

e

n

t

s

a

n

d

f

i

g

l

o

t

i

n

g

v

e

h

i

c

l

e

s

.

!

B

u

t

a

l

l

m

e

t

a

l

s

r

e

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

o

n

l

y

0

.

3

%

o

f

P

P

,

I

s

o

p

o

t

e

n

t

i

a

l

g

a

i

n

s

a

r

e

I

I

I

I

P

r

o

d

u

c

e

d

b

y

s

m

a

l

l

u

n

i

t

s

;

w

e

i

g

h

t

o

f

p

u

b

.

p

u

r

c

h

.

i

s

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

R

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

l

i

k

e

l

y

;

n

e

w

m

i

n

e

s

a

r

e

m

o

r

e

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

.

A

l

s

o

m

o

r

e

J

r

d

c

o

u

n

t

r

y

t

r

a

d

e

-

c

l

o

s

u

r

e

s

e

x

p

e

c

t

e

d

N

o

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

P

P

C

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

w

o

r

l

d

m

a

r

k

e

t

F

r

e

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

-

n

o

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

t

i

c

p

o

l

i

c

y

0

X

0

0

0

P

r

o

b

a

b

l

e

p

r

o

c

e

s

s

i

n

g

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

-

(

X

)

b

u

t

n

o

i

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

l

i

k

e

l

y

t

o

b

e

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

N

o

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

b

e

y

o

n

d

0

e

x

i

s

t

i

n

g

s

i

z

e

-

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

i

c

c

o

n

s

i

d

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

,

f

u

e

l

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

e

t

c

.

N

o

r

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

e

.

G

e

o

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

c

o

n

s

t

r

a

i

n

t

s

N

o

r

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

e

x

c

e

p

t

c

l

o

s

u

r

e

o

f

e

x

i

s

t

i

n

g

m

i

n

e

s

i

n

f

a

v

o

u

r

o

f

n

o

n

-

E

C

i

m

p

o

r

t

s

P

P

i

s

l

e

s

s

t

h

a

n

2

%

o

f

s

e

c

t

o

r

o

u

t

p

u

t

,

s

o

P

P

h

a

s

n

o

e

f

f

e

c

t

o

n

r

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

.

e

x

c

e

p

t

a

)

S

t

e

e

l

t

u

b

e

s

:

w

a

t

e

r

s

e

c

t

o

r

i

s

a

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

r

,

b

u

t

t

h

e

r

e

i

s

n

o

e

v

i

d

e

n

c

e

o

f

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

t

i

c

b

u

y

i

n

g

b

)

S

p

e

c

i

a

l

s

t

e

e

l

s

:

f

o

r

d

e

f

e

n

c

e

,

a

e

r

o

s

p

a

c

e

a

n

d

n

u

c

l

e

a

r

1

n

d

u

s

t

r

i

e

s

.

T

o

t

a

l

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

o

f

t

h

e

s

e

t

w

o

i

t

e

m

s

i

s

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

0

0

0

X

X

T

A

B

L

E

2

.

1

-

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

O

F

P

R

O

D

U

C

T

S

F

O

R

P

O

T

E

N

T

I

A

L

B

E

N

E

F

I

T

S

F

R

O

M

T

H

E

I

N

T

E

R

N

A

L

M

A

R

K

E

T

(

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

M

A

C

E

/

D

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

o

n

2

2

4

n

o

n

f

e

r

r

o

u

s

m

e

t

a

l

s

F

1

-

0

2

3

M

i

n

i

n

g

o

f

n

o

n

m

e

t

a

l

l

i

c

m

i

n

e

r

a

l

s

2

4

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

e

o

f

n

o

n

-

m

e

t

a

l

l

i

c

1

-

0

m

i

n

e

r

a

l

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

F

2

5

C

h

e

m

i

c

a

l

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

2

6

M

a

n

-

m

a

d

e

f

i

b

r

e

s

1

-

0

F

3

:

M

E

T

A

L

M

A

N

U

F

A

C

T

U

R

E

,

M

E

C

H

/

E

L

E

C

.

E

N

G

3

1

M

e

t

a

l

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

s

3

2

M

e

c

h

a

n

i

c

a

l

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

%

o

f

P

P

5

.

5

0

.

9

P

P

/

I

o

u

t

p

u

t

2

2

.

5

0

.

5

S

t

a

t

i

c

P

r

i

c

e

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

l

y

t

r

a

d

e

d

c

o

u

m

a

d

i

t

y

(

n

o

t

e

:

P

P

s

h

a

r

e

o

f

o

u

t

p

u

t

i

s

h

i

g

h

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

l

o

c

a

l

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

i

s

s

m

a

l

l

c

o

m

p

a

r

e

d

t

o

i

m

p

o

r

t

s

)

I

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

I

I

r

e

j

e

c

t

I

I

o

I

I

I

I

I

I

P

P

l

i

m

i

t

e

d

t

o

a

s

p

h

a

l

t

a

n

d

r

o

a

d

m

a

k

i

n

g

I

0

m

a

t

e

r

i

a

l

s

.

O

t

h

e

r

r

o

a

d

m

a

t

e

r

i

a

l

s

a

r

e

h

i

g

h

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

c

o

s

t

/

l

o

w

v

a

l

u

e

c

o

m

m

o

d

i

t

i

e

s

o

f

l

o

c

a

l

s

u

p

p

l

y

0

.

5

c

2

.

0

P

P

a

r

e

c

e

m

e

n

t

,

c

o

n

c

r

e

t

e

r

o

a

d

m

a

k

i

n

g

0

.

6

2

.

2

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

,

c

o

n

c

r

e

t

e

s

t

r

e

e

t

f

u

r

n

i

t

u

r

e

a

n

d

3

.

2

1

.

1

2

.

1

1

.

8

2

.

7

6

.

5

c

e

r

a

m

i

c

s

a

n

i

t

a

r

y

w

a

r

e

.

P

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

m

a

y

e

x

i

s

t

f

o

r

f

o

r

w

h

i

c

h

c

a

r

t

e

1

s

h

a

v

e

e

i

l

'

S

t

e

i

f

i

n

t

l

o

e

p

a

s

t

5

.

5

M

a

i

n

l

y

c

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

i

n

t

e

r

.

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

m

a

r

k

e

t

s

2

.

4

w

i

t

h

m

a

i

n

l

y

p

r

i

v

a

t

e

s

e

c

t

o

r

n

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

r

s

,

e

x

c

e

p

t

:

P

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

s

(

m

a

i

n

l

y

p

u

b

l

i

c

s

e

c

t

o

r

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

r

s

a

n

d

m

o

n

o

p

o

l

y

s

u

p

p

l

i

e

r

s

)

E

x

p

l

o

s

i

v

e

s

(

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

e

d

!

5

.

5

M

o

s

t

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

h

a

v

e

a

p

r

i

v

a

t

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

,

3

.

3

b

u

t

P

P

a

r

e

c

o

n

c

e

n

t

r

a

t

e

d

i

n

d

f

e

w

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

f

o

r

w

h

i

c

h

t

h

e

r

e

i

s

1

i

t

t

l

e

p

,

i

v

a

t

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

:

-

3

1

4

/

3

1

5

h

e

a

v

y

s

t

e

e

l

f

a

b

r

i

c

n

t

i

o

n

-

b

r

i

d

g

e

s

-

l

a

r

g

e

b

o

i

l

e

r

s

-

v

e

s

s

e

l

s

3

1

4

.

3

p

i

t

p

r

o

p

p

i

n

g

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

3

1

4

.

4

r

a

i

l

w

a

y

t

r

a

c

k

a

n

d

f

i

t

t

i

n

g

s

T

o

t

a

1

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

,

h

o

w

e

v

e

r

,

a

.

e

s

m

a

1

1

(

2

%

o

f

t

o

t

a

l

)

5

.

5

M

a

i

n

l

y

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

f

o

r

i

n

d

u

s

t

y

.

S

a

l

e

s

9

.

3

t

o

p

u

b

l

i

c

s

e

c

t

o

r

:

3

2

5

.

1

m

i

n

i

n

g

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

(

o

a

l

I

H

V

A

C

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

(

o

f

f

i

c

e

s

)

e

q

u

i

p

.

f

o

r

s

t

e

e

l

,

;

h

i

p

b

u

i

l

d

i

n

g

,

c

a

r

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

.

I

t

i

s

l

i

k

e

l

y

t

h

a

t

p

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

e

x

i

s

t

f

o

r

s

o

m

e

o

f

t

h

e

s

e

i

t

e

m

s

-

b

u

t

c

o

m

p

a

r

i

s

o

n

s

w

o

u

l

d

b

e

v

i

r

t

u

a

l

l

y

i

m

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

e

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

s

p

e

c

i

f

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

X

X

X

X

X

X

(

X

)

(

X

)

(

X

)

R

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

/

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

S

c

a

l

e

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

l

y

n

o

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

.

M

a

i

n

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

a

r

e

l

i

k

e

l

y

t

o

b

e

g

o

l

d

,

o

t

h

e

r

v

a

l

u

a

b

l

e

m

e

t

a

l

s

f

o

r

s

t

r

a

t

e

g

i

c

s

t

o

c

k

p

i

l

e

s

,

a

l

l

o

y

s

f

o

r

a

e

r

o

s

p

a

c

e

a

n

d

a

r

m

a

m

e

n

t

s

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

-

a

w

i

d

e

r

a

n

g

e

o

f

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

,

m

a

i

n

l

y

i

m

p

o

r

t

e

d

N

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

N

o

r

e

s

t

r

i

c

t

i

o

n

s

o

n

s

c

a

l

e

M

a

i

n

p

r

o

d

u

c

e

r

s

o

f

b

u

l

k

c

h

e

m

i

c

a

l

s

a

r

e

i

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

.

C

h

e

m

i

c

a

l

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

a

n

d

p

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

s

h

a

v

e

n

o

r

e

s

t

r

i

c

t

i

o

n

o

n

s

c

a

l

e

:

p

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

s

i

s

t

e

n

d

i

n

g

t

o

o

l

i

g

o

p

o

l

y

T

h

e

h

e

a

v

y

f

a

b

r

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

e

c

t

o

r

i

s

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

t

u

p

o

n

p

u

6

l

1

c

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

.

I

t

1

s

a

d

e

c

l

i

n

i

n

g

!

s

e

c

t

o

r

a

n

d

r

e

c

e

i

v

e

s

g

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

I

f

o

r

r

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

.

T

h

e

r

e

i

s

l

i

k

e

l

y

t

o

b

e

s

c

o

p

e

f

o

r

E

u

r

o

p

e

a

n

r

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

i

n

,

e

g

.

,

p

o

w

e

r

s

t

a

t

i

o

n

b

o

i

l

e

r

m

a

k

i

n

g

M

a

y

b

e

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

i

n

m

i

n

i

n

g

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

r

e

j

e

c

t

0

0

0

X

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

,

s

t

e

e

l

p

l

a

n

t

,

e

t

c

-

t

h

e

s

e

a

r

e

i

n

c

.

a

l

s

o

p

a

r

t

o

f

t

h

e

h

e

a

v

y

s

t

e

e

l

f

a

b

r

i

c

a

t

1

0

n

a

b

o

v

e

s

e

c

t

o

r

(

3

1

)

V

I

"

'

V

I

T

A

B

L

E

2

.

1

-

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

O

F

P

R

O

D

U

C

T

S

F

O

R

P

O

T

E

N

T

I

A

L

B

E

N

E

F

I

T

S

F

R

O

M

T

H

E

I

N

T

E

R

N

A

L

M

A

R

K

E

T

(

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

N

A

C

E

/

D

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

o

n

3

3

O

f

f

i

c

e

m

a

c

h

i

n

e

r

y

1

-

0

3

7

I

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

s

I

3

4

E

l

e

c

t

r

i

c

a

l

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

1

-

0

F

(

;

n

c

3

3

)

3

5

M

o

t

o

r

v

e

h

i

c

l

e

s

1

-

0

3

6

O

t

h

e

r

m

e

a

n

s

o

f

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

3

7

I

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

4

:

O

T

H

E

R

M

A

N

U

F

A

C

T

U

R

I

N

G

4

1

/

2

F

o

o

d

,

d

r

i

n

k

a

n

d

t

o

b

a

c

c

o

4

3

/

4

5

T

e

x

t

i

l

e

s

a

n

d

c

l

o

t

h

i

n

g

F

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

%

P

P

/

I

I

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

I

I

r

e

j

e

c

t

o

f

P

P

o

u

t

p

u

t

!

S

t

a

t

i

c

P

r

i

c

e

A

d

v

a

n

t

a

g

e

1

.

9

4

.

4

1

3

.

5

1

.

8

1

.

9

8

.

3

1

0

.

6

1

.

7

0

.

3

0

.

7

0

.

6

1

3

.

8

1

0

.

4

2

1

.

4

4

.

0

2

.

2

I

P

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

e

x

i

s

t

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

d

i

s

c

r

i

m

i

n

a

t

o

r

y

p

r

i

c

i

n

g

b

y

m

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

e

r

s

.

T

r

a

d

e

i

s

i

m

p

e

d

e

d

b

y

c

u

s

t

o

m

s

r

e

g

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

a

n

d

e

l

e

c

t

r

i

c

a

l

s

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

s

,

J

n

d

s

o

m

e

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

i

n

g

.

P

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

w

o

u

l

d

n

o

t

b

e

m

f

!

a

s

u

r

a

b

l

e

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

p

e

r

f

o

r

m

a

n

c

e

P

u

b

l

i

c

s

e

c

t

o

r

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

3

4

1

C

a

b

l

e

s

3

4

2

P

o

w

e

r

g

e

n

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

3

4

4

T

e

l

e

c

o

m

m

s

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

3

4

4

B

r

o

a

d

c

a

s

t

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

3

4

7

E

l

e

c

.

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

/

l

i

g

h

t

i

n

g

f

o

r

o

f

f

i

c

e

s

3

4

7

R

o

a

d

l

i

g

h

t

i

n

g

T

h

e

r

e

i

s

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

t

i

c

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

i

n

g

,

p

a

r

t

l

y

d

u

e

t

o

h

e

r

i

t

a

g

e

o

f

e

q

u

i

p

r

r

e

n

t

&

s

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

s

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

a

r

e

f

r

e

e

l

y

t

r

a

d

e

d

.

"

N

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

"

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

h

a

v

e

a

h

i

g

h

f

o

r

e

i

g

n

c

o

n

t

e

n

t

.

T

h

e

r

e

a

r

e

p

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

t

l

b

l

s

d

u

e

p

a

r

t

l

y

t

o

s

u

p

p

l

i

e

r

s

'

d

i

s

c

r

i

m

i

n

a

t

o

r

y

p

r

i

c

i

n

g

p

o

l

i

c

i

e

s

-

s

o

g

a

i

n

s

f

r

o

m

t

r

a

d

e

a

r

e

d

i

f

f

i

c

u

l

t

(

b

u

t

P

P

c

a

n

b

e

a

s

a

l

e

v

e

r

t

o

b

r

e

a

k

c

a

r

t

e

l

p

r

i

c

i

n

g

)

(

X

)

X

X

X

X

0

0

X

5

6

.

0

T

h

i

s

I

s

t

h

e

a

r

e

a

I

n

w

h

i

c

h

n

l

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

s

t

i

c

2

3

.

9

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

i

n

g

m

o

s

t

a

p

p

l

i

e

s

,

i

n

p

a

r

t

i

c

u

l

a

r

:

3

6

1

s

h

i

p

b

u

i

l

d

i

n

g

3

6

2

r

a

i

l

w

a

y

r

o

l

l

i

n

g

s

t

o

c

k

(

X

)

3

6

4

a

e

r

o

s

p

a

c

e

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

(

X

)

H

o

w

e

v

e

r

,

p

r

i

c

e

s

c

a

n

n

o

t

b

e

l

O

m

p

a

r

e

d

(

X

)

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

s

p

e

c

i

f

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

1

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

(

I

n

c

l

u

d

e

d

i

n

3

3

a

b

o

v

e

)

.

T

h

e

r

e

i

s

g

e

n

e

r

a

l

l

y

0

e

x

t

e

n

s

i

v

e

t

r

a

d

e

i

n

t

h

e

s

e

i

t

e

m

s

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

I

t

h

e

s

e

c

t

o

r

i

s

v

e

r

y

s

p

e

c

i

a

l

i

s

e

d

.

A

n

a

r

e

a

I

w

h

e

r

e

t

h

e

r

e

m

a

y

b

e

s

c

o

p

e

f

o

r

w

i

d

e

r

I

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

i

n

g

i

s

M

e

d

i

c

a

l

E

q

u

l

_

p

n

e

n

t

I

I

I

I

1

.

9

l

o

c

a

l

s

u

p

p

l

y

n

o

r

m

a

l

l

y

r

e

q

u

i

r

e

d

b

y

p

u

b

l

i

c

I

0

.

3

e

s

t

a

b

l

i

s

h

m

e

n

t

.

W

i

d

e

r

a

n

g

e

o

f

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

,

I

0

e

a

c

h

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

i

n

t

o

t

a

l

P

P

I

I

1

.

6

I

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

i

t

e

m

s

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

i

n

g

,

I

0

1

.

1

a

l

t

h

o

u

g

h

p

r

i

c

e

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

m

a

y

e

x

i

s

t

,

I

(

X

)

e

g

.

f

o

r

u

n

i

f

o

r

m

s

I

I

R

e

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

/

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

S

c

a

l

e

C

o

m

p

u

t

e

r

s

h

a

v

e

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

e

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

i

n

R

&

D

a

n

d

m

a

r

k

e

t

i

n

g

(

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

c

o

m

p

a

t

i

b

i

l

i

t

y

)

.

M

o

s

t

i

n

s

t

r

u

m

e

n

t

s

m

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

e

i

s

s

m

a

l

l

-

s

c

a

l

e

a

n

d

t

h

e

r

e

i

s

e

x

t

e

n

s

i

v

e

t

r

a

d

e

T

h

e

r

e

a

r

e

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

e

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

o

f

s

c

a

l

e

i

n

p

o

w

e

r

g

e

n

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

t

e

l

e

c

o

m

m

s

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

a

n

d

p

e

r

h

a

p

s

b

r

o

a

d

c

a

s

t

e

q

u

i

p

m

e

n

t

(

b

u

t

r

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

l

y

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

a

n

d

a

l

r

e

a

d

y

i

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

s

u

p

p

l

y

)

A

l

r

e

a

d

y

E

u

r

o

p

e

a

n

s

c

a

l

e

m

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

A

l

l

t

h

e

t

h

r

e

e

s

u

b

s

e

c

t

o

r

s

l

i

s

t

e

d

a

r

e

o

p

e

r

a

t

i

n

g

b

e

l

o

w

o

p

t

i

m

u

m

c

a

p

a

c

i

t

y

i

n

E

C

c

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

s

h

i

p

b

u

i

l

d

i

n

g

r

a

i

l

w

a

y

r

o

l

l

i

n

g

s

t

o

c

k

a

e

r

o

s

p

a

c

e

N

o

r

e

s

t

r

i

c

t

i

o

n

o

n

s

c

a

l

e

o

f

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

.

P

u

b

l

i

c

s

e

c

t

o

r

i

s

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

c

h

a

s

e

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

s

e

c

t

o

r

i

s

i

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

r

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

u

n

i

f

o

r

m

s

.

N

o

r

e

s

t

r

i

c

t

i

o

n

o

n

s

c

a

l

e

o

f

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

r

e

j

e

c

t

X

0

X

X

0

X

X

X

0

0

0

T

A

B

L

E

2

.

1

-

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

I

O

N

O

f

P

R

O

D

U

C

T

S

F

O

R

P

O

T

E

N

T

I

A

L

B

E

N

E

F

I

T

S

F

R

O

M

T

H

E

I

N

T

E

R

N

A

L

M

A

R

K

E

T

(

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

N

A

C

E

!

D

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

o

n

4

4

/

4

5

L

e

a

t

h

e

r

g

o

o

d

s

/

f

o

o

t

w

e

a

r

4

6

4

7

4

8

4

9

T

i

m

b

e

r

a

n

d

w

o

o

d

e

n

f

u

r

n

i

t

u

r

e

P

a

p

e

r

a

n

d

p

r

i

n

t

i

n

g

R

u

b

b

e

r

a

n

d

p

l

a

s

t

i

c

s

O

t

h

e

r

m

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

5

:

C

O

N

S

T

R

U

C

T

I

O

N

A

N

D

C

I

V

I

L

E

N

G

I

N

E

E

R

I

N

G

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

I

-

0

F

1

-

0

F

6

:

D

I

S

T

R

I

B

U

T

I

V

E

T

R

A

D

E

S

1

-

0

F

7

:

T

R

A

N

S

P

O

R

T

A

N

D

C

O

M

M

U

N

I

C

A

T

I

O

N

I

-

0

F

o

f

w

h

i

c

h

7

5

a

i

r

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

1

-

0

8

:

B

A

N

K

I

N

G

A

N

D

F

I

N

A

N

C

E

,

R

E

A

L

E

S

T

A

T

E

8

1

/

8

2

C

r

e

d

i

t

a

n

d

i

n

s

u

r

a

n

c

e

1

-

0

%

P

P

/

I

!

A

c

c

e

p

t

/

I

r

e

j

e

c

t

I

o

f

P

P

o

u

t

p

u

t

!

S

t

a

t

i

c

P

r

i

c

e

A

d

v

a

n

t

a

g

e

0

.

1

0

.

1

0

.

6

0

.

1

2

.

8

0

.

4

0

.

7

0

.

4

0

.

4

2

8

.

6

2

6

.

8

4

.

5

7

.

7

5

.

4

0

.

8

0

.

5

1

.

9

I

1

.

4

I

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

.

O

n

l

y

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

1

.

0

i

t

e

m

i

s

a

r

m

y

/

p

o

l

i

c

e

b

o

o

t

s

3

.

0

I

n

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

t

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

s

;

h

i

g

h

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

1

.

5

c

o

s

t

s

:

o

n

l

y

P

P

i

t

e

m

o

f

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

c

e

i

s

s

c

h

o

o

l

/

o

f

f

i

c

e

d

e

s

k

s

8

.

6

P

r

i

n

t

i

n

g

a

n

d

p

u

b

l

i

s

h

i

n

g

i

s

s

u

b

j

e

c

t

t

o

1

.

3

l

a

n

g

u

a