Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Vaughn Households Crafts

Cargado por

Fernando Padilla DezaDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Vaughn Households Crafts

Cargado por

Fernando Padilla DezaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Society for American Archaeology

Households, Crafts, and Feasting in the Ancient Andes: The Village Context of Early Nasca

Craft Consumption

Author(s): Kevin J. Vaughn

Source: Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), pp. 61-88

Published by: Society for American Archaeology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4141564 .

Accessed: 25/03/2013 07:53

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Latin

American Antiquity.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HOUSEHOLDS, CRAFTS,

AND FEASTING IN THE ANCIENT ANDES:

THE VILLAGE CONTEXT OF EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION

Kevin J.

Vaughn

Craft consumption

in

Early

Nasca

(ca.

A.D.

1-450) society

is

explored by evaluating

the use

of polychrome pottery

within

the context

of

a residential

village.

Data are

presented from

the

Early

Nasca

village, Marcaya,

where excavations

utilizing

a household

archaeology approach

revealed that most

polychromes

were consumed

by

households with

high

and low sta-

tus

alike, while certain vessel

shapes

were

reservedfor high-status

households. These

findings challenge

the common

assump-

tion that

highly

valued

crafts

were

monopolized by

elites in

middle-range

societies, and show instead that there is a

potential

demand

for crafts by

both elites and commoners. It is

argued

that

polychrome pottery

was

broadly

used in Nasca because

it was

integral

to ritual

consumption

that

first

took

place

in

feasting

ceremonies at the

regional

center Cahuachi, while cer-

tain vessel

types

were restricted to

high-status

households that acted as intermediaries between Cahuachi and the

village.

Recientemente, los

arque6logos

han

dirigido

su

atencidn

mds al uso de los

productos

artesanales en las sociedades de caci-

cazgos.

Los estudios han demostrado

que

el uso de estos

productos

en las culturas

prehispdnicasfue

mucho mds

complicado

de lo

que

se habia

previamente sugerido.

No

obstante, los andlisis han tendido a

favorecer

estudios con un

enfoque

al con-

sumo de las dlites. Este articulo

explora

cdmo los

productos

artesenales

fueron

utilizados

por

las dlites

y

los

plebeyos.

El

enfoque

es la sociedad Nasca

Temprano (1-450

d.

C.)

donde se

evallia

el consumo de la cerdmica

policroma

dentro del con-

texto de

Marcaya,

una aldea residencial. Las

investigaciones que

utilizan la

perspectiva

de la

arqueologia

domdstica reve-

laron

que

una cerdmica

policroma fue

utilizada

por

individuos de estatus alto

y bajo.

Por otro

lado,

ciertos

tipos

de

vasijas

fueron

reservados

para

las dlites. Se

sugiere que

debido a su uso ritual, la cerdmica

policroma disfrutd

de una distribucio'n

extensa en la sociedad Nasca

Temprana,

tanto en las

aldeas como en los centros ceremoniales como Cahuachi,

donde

fue

usada en las ceremonias. Los resultados del estudio tienen

implicaciones para

nuestra

comprensidn

del modo de

incorpo-

racidn de los

productos

artesanales en las

economias

de las sociedades de

cacicazgos.

The

nature of

crafts,

and the

ways

in which

finely

made

material

objects

are

integrated

into the economies of

middle-range

soci-

eties,

has been the

subject

of a

growing

number of

archaeological investigations (Ames 1995;

Bay-

man

1999;

Costin

2001;

Costin and

Wright

1998;

Mills

2000;

Shimada

1998;

Spielmann 2002).

Tra-

ditionally,

studies that evaluate crafts have followed

a basic

dichotomy

between

highly

valued

prestige

goods monopolized by

elites and

ordinary

utilitar-

ian

goods

that

enjoyed

unrestricted distribution

(e.g.,

Brumfiel and Earle

1987;

Frankenstein and

Rowlands

1978).

It is often

argued

that crafted

pres-

tige goods

were valuable for the social

reproduc-

tion of

elites,

while non-elites did not have the

means or the reasons to finance the

production

of

these

goods. Recently, however,

there has been a

general

dissatisfaction with these dichotomous

models to

explain

the social and economic uses of

crafts in

middle-range

societies

(Bayman

2002;

Costin

2001;

Costin and

Wright

1998;

Inomata

2001;

Spielmann

2002;

Trubitt

2000).

In

particu-

lar,

it is now

recognized

that there was a

potential

demand for crafts from all sectors of

society,

and

that crafts moved

through

various

segments

of soci-

ety

in

complex

economic

patterns

not

easily

explainable by

traditional models.

For

example,

in a

critique

of the

prestige-goods

model,

which assumes that social valuables were

monopolized by

elites in an effort to

gain political

power (e.g.,

Brumfiel and Earle

1987;

Friedman

and Rowlands

1978), Bayman (2002)

has

argued

that Hohokam marine shell ornaments were not

simply prestige goods produced

for and used exclu-

Kevin

J. Vaughn

n

Department

of

Anthropology,

Pacific Lutheran

University,

Tacoma,

WA 98447-0003

(vaughn@plu.edu)

Latin American

Antiquity, 15(1), 2004, pp.

61-88

Copyright@

2004

by

the

Society

for American

Archaeology

61

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62

LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

[Vol. 15,

No.

1,

2004

sively by

elites.

Instead,

these artifacts had differ-

ent roles in Hohokam

society

as

symbols

of

group

identity, insignia

of

office,

as well as instruments

of

power,

and were used

by

a

variety

of social

groups

that included elites and commoners

(Bay-

man

2002:70). Importantly,

this

study implies

that

simple

models such as the

prestige-goods

model

fail to take into account the different roles and

meanings

of crafts in

middle-range

societies

(Bay-

man

2002:74).

Recent evidence

suggests

that

finely painted

polychrome pottery

of the

Early

Intermediate

period

Nasca culture also does not fit

easily

into a

dichotomy

of

prestige

versus utilitarian

good.

This

dichotomy

fails to

adequately

describe and

explain

the

production, circulation,

and

consumption

of

these items.

Though polychromes

were

finely

made

(Carmichael 1990),

are well-known as the

princi-

pal

vehicle of Nasca

ideology (Carmichael 1998),

and were

employed by foreign

elites outside of the

immediate Nasca

region

as

status-enhancing pres-

tige goods (Carmichael 1992a;

Goldstein

2000;

Sil-

verman

1997;

Valdez

1998),

within the Nasca

heartland

polychromes appear

to have been con-

sumed

by

varied

segments

of

society,

not

just

elites

(Carmichael 1988, 1995, 1998). Furthermore,

while

production

of these items was restricted and indica-

tive of

specialization (Vaughn

and Neff

2000),

their

consumption, paradoxically,

was not restricted.

I evaluate the contradiction between the

restricted

production yet widespread

distribution of

Nasca

polychromes.

I situate the discussion

by

con-

sidering

the

consumption

of

highly

valued crafts in

middle-range

societies,

highlighting

recent research

that

suggests

there was a demand for crafts in mid-

dle-range

societies from both elites and non-elites.

I

argue

that one

way

for non-elites to obtain crafts

was

through

the commensal

politics

of ceremonial

feasting.

I

present primary

data from the

Early

Nasca

domestic

site,

Marcaya,

where excavations under-

taken from the

perspective

of household archaeol-

ogy

revealed that a

large quantity

of

polychromes,

particularly

bowls and

vases,

was consumed

by

households of both

high

and low status even

though

these items were

produced

elsewhere.

I

argue

that

polychrome

bowls and vases were consumed

widely

in Nasca

society

because

they

were

integral

to rit-

ual

consumption

first carried out in

feasting

cere-

monies at Cahuachi, the

region's

ceremonial center.

Certain vessel

types,

modeled

headjars

in

particu-

lar, however,

were restricted to

high-status

house-

holds at

Marcaya.

I

suggest

that their restricted con-

sumption

is related to

prestige-building

activities

by

high-status

individuals and households who

may

have been intermediaries between

regional

cere-

monial centers and

villages.

Crafts, Consumption,

and

Feasting

in

Middle-Range

Societies

While a definition of "craft"

potentially

includes

any

material

object

made

by

humans

(Costin 1998),

a more narrow definition is

employed

here. A craft

is defined as

any object

or

group

of

objects

manu-

factured

by

skills that not all members of

society

have. In other

words,

crafts are

objects produced

in the context of

specialization,

no matter the

scale,

intensity,

or context of that

specialization (e.g.,

Costin

1991).

Research in the last two decades has

suggested

that the

specialized production

of crafts was inte-

gral

to

many

nonstratified, middle-range,

and even

small-scale societies.

Furthermore,

crafts were

pro-

duced, circulated,

and consumed in

very complex

economic

systems

within these smaller-scale soci-

eties

(Arnold

and Munns

1994;

Bayman

1999;

Clark

1995;

Clark and

Parry

1990;

Cross

1993;

Sassaman

1998;

Spielmann 2002).

Crafts

and

Consumption

Studies of craft

specialization

have tended to favor

the

analysis

of craft

production

over other

stages

of

what can be referred to as the "craft

economy" (Bay-

man

1999).

Craft

consumption

in

particular

has seen

little

explicit

treatment when

compared

to

produc-

tion,

even

though

much of what

archaeologists study

is

directly

related to

consumption

in one form or

another

(Smith 1998). I

follow Smith's (1998:115)

general

definition of

consumption by defining

craft

consumption

as the

selection, use, maintenance,

repair,

and discard of an item after it has been

pro-

duced and circulated. Craft

consumption

is an

important

avenue of

inquiry

because without under-

standing

what

segments

of

society

consumed them

and in what contexts, it is difficult to

postulate

exactly why

crafts were

produced

in the first

place.

This is

especially

the case because

production

is

generally organized

to meet consumer demands

(Costin 2001:306; Morrison 1994; Smith 1998),

no

matter who those consumers

might

have been.

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 63

Not

surprisingly,

when

consumption

has been

considered in the

analysis

of

archaeological

data,

discussion is dominated

by

the elite

consumption

of

crafts,

as these individuals are often assumed to

be the most

important

consumers of these

goods.

While crafted

goods

were vital to elites in the

polit-

ical

economy

of

preindustrial

societies

primarily

as a form of wealth finance

(e.g.,

Earle

1997),

stud-

ies have

rarely emphasized

the

consumption

of

crafts

by

non-elites even

though

recent research

suggests

that

they

were

important

to this

segment

of

society

as well

(Bayman

2002;

Wattenmaker

1998).

One reason is

that,

whether

implicit

or

explicit,

a distinction is

usually

made between crafts

produced

for

people

in

positions

of social and

polit-

ical

power

or

prominence,

and crafts

manufactured

for the "mundane

spheres

of life"

(Helms 1993:14).

Helms

(1993, 1999)

makes the distinction unam-

biguously

as she reserves the term "skilled craft-

ing"

of

goods

for "elite related 'states or forms of

meaning"' (Helms 1993:14). Furthermore,

the

products

of skilled

crafting

are reserved for

public,

political spheres

while

"ordinary" goods

are made

for the

private

domestic

sphere (Helms 1993:14).

There are theoretical reasons to assume that the

products

of skilled

crafting, implying

a certain level

of

competence,

were reserved for those in a

posi-

tion of

power.

The

primary

reason,

of

course,

is that

elites are the

only

members of

society

with the

resources to finance these endeavors

(Brumfiel

and

Earle

1987;

Earle

1991, 1997). Highly

valued

crafted

goods

are well known as

symbols

of

power

and

insignia

of office for elites in non-state soci-

eties

(e.g.,

Helms

1999). However,

have archaeol-

ogists

dismissed the

possibility

that other members

of

society

could access these

goods?

Need we

assume that under all circumstances the

products

of skilled

crafting

were reserved

only

for those in

positions

of

power?

For

example,

Lecount

(1999)

demonstrates that

commoners of the Terminal Classic at Xunantunich

also consumed

highly

valued

goods

that were dis-

tributed to them

by

elites

(LeCount 1999:254).

LeCount describes a shift in the distribution of

polychrome pottery

at two sites in Belize between

the Late Classic

II phase

and the Terminal Classic.

While

previously

limited to elite contexts

during

the Late Classic II, polychrome pottery enjoyed

unrestricted distribution

during

the Terminal Clas-

sic (LeCount 1999:251). LeCount

argues

that

poly-

chrome

pottery

was distributed

equally

across

social

groups during

the Terminal Classic because

elites at the time

emphasized community

solidar-

ity

while

building

vertical alliances and

symboliz-

ing

shared

power by gifting

these crafted items to

commoners

(LeCount 1999:254), resulting

in the

relatively widespread

distribution of

polychrome

pottery.

The

importance

of this case

study

is its demon-

stration of how a crafted item

(polychrome pottery)

moves

through

various social strata

by

means of

the

political strategies employed by

elites.

Thus,

tracing

the distribution and

consumption

of this

particular

artifact class revealed

important insights

into Terminal Classic

political strategies.

Other studies have

suggested

a

potential

demand

for crafts

by

both elites and non-elites. For exam-

ple,

Wattenmaker

(1998)

has

proposed

that crafts

embody culturally meaningful symbolic

commu-

nication and that information is embedded in some

crafts that

appeal

to all members of a social

group,

not

just

elites.

Indeed, crafts,

especially highly

vis-

ible ones such as

serving

vessels, cloth,

and

per-

sonal

adornments,

provide

material evidence of

group membership (Bayman

2002:80;

Costin

1998:3;

Wobst

1977), symbolize

the

identity

of

their

producers

and consumers

(Chilton 1999),

and

continuously

reinforce this

intragroup identity

(Hodder 1982).

These factors contribute to a

demand for crafts

by people

from all

segments

of

society.

Crafts

and the Politics

of Feasting

While there

may

be a demand for crafts

by

all

seg-

ments of

society, obtaining

them is

problematic

for

individuals and

groups

who lack the means and the

resources to do so. The

example

from the Termi-

nal Classic illustrates that elites can use

highly

val-

ued crafts as

political currency by giving

them to

commoners in an effort to build

community

soli-

darity.

One social arena in which non-elites can

obtain

goods

in this fashion is

through

the com-

mensal

politics

of

feasting

ceremonies

(e.g.,

Dietler

1990, 1996; Dietler and

Hayden 2001a), "events

...

constituted

by

the communal

consumption

of food

and/or drink" (Dietler

and

Hayden 2001b:3). Feasts

are

"inherently political" (Dietler 2001:66), and

feasting

as a social and communal act

provides

the

opportunity

for

political action, status

negotiation,

and social

change (Dietler 1990, 2001; Hayden

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 15,

No.

1,

2004

1996, 2001;

Junker

2001;

Lau

2002;

LeCount

2001;

Potter

2000).

As instruments of

change,

feasts

provide oppor-

tunities for

sponsors

to enhance their

status,

often

accomplished through

the

display

of

goods

includ-

ing important

artifacts

(DeMarrais

et al.

1996;

Wiessner

2001:116)

and

through gift giving (Clark

and Blake

1994:21;

Dietler

1996:91;

LeCount

1999;

Perodie

2001). By

their

very

nature feasts cre-

ate

reciprocal obligations

between host and

guest

(Lau 2002:280) through

the

gifting

of food and

drink as well as items of material

import.

A well-known

ethnographic example

of the rela-

tionship

between

gifting

and status enhancement is

the Northwest Coast

potlatch

characterized

by

the

distribution of

large quantities

of food and

goods

(Piddocke 1965).

Potlatches were

highly political

venues of status

display

where social

prestige

was

obtained and enhanced

(see

Boas

1966).

Piddocke

(1965) suggests

that

potlatches provided opportu-

nities for

sponsors

to

display

their

generosity by

dis-

tributing

food and

wealth, thereby enhancing

their

social

prestige.

The

potlatch, then,

provides

one

ethnographic example

where the mechanism of

communal

feasting

afforded the

opportunity

for

par-

ticipants, including

non-elites,

to obtain

highly

val-

ued crafts in the form of

gifts given by

feast

sponsors.

Feasting

in the Andes.

Ethnographic,

ethnohis-

toric,

and

archaeological

studies have demonstrated

that

feasting

was

prevalent throughout

the

prehis-

panic

Andes. Andean "work

party

feasts" featur-

ing

the distribution of abundant

quantities

of chicha

maize beer were

given

for workers in

exchange

for

their

participation

in labor

projects (Lau 2002).

Such feasts are well known

among

modem

indige-

nous

groups (Allen 1988),

the Inka

Empire (Bray

2003;

Morris

1979;

Murra

1980),

and

pre-Inka

Andean societies as well

(Gero 1992;

Hastorf and

Johannessen

1993;

Lau

2002;

Moore

1989;

Mose-

ley 1975).

A clear

example

of

feasting

in a

middle-range

Andean

society

is documented

among

the

Early

Intermediate

period Recuay.

Lau (2002) argues

that

by

A.D. 500, evidence for

public

ceremonies

involving

both ancestor

worship

and

public

feast-

ing

was

apparent

at Chinchawas, a

high-altitude

Recuay

site in the Cordillera

Negra

near Huaraz.

During

the earlier

Kaytin

and Chinchawasi

phases

(A.D. 500-800),

the

occupation

was characterized

by public feasting clearly

associated with

high-sta-

tus residences. These feasts were arenas

whereby

local elites made efforts to enhance their status

through

wealth

display

of

sumptuary goods

and the

consumption

of

large quantities

of chicha and

camelid meat

(Lau 2002:298).

In

contrast,

the later

Warmi

phase (afterA.D. 800)

was characterized

by

smaller-scale ceremonies

consisting

of

dedicatory

offerings

and ritual

drinking.

This local shift is

explained

as the result of Wari

expansion

into the

region

(Lau 2002:300).

This

example

illustrates the

importance

of feast-

ing

in the

early development

of Andean middle-

range

societies.

Feasting

was a critical social

setting

in which local elites were able to

garner prestige

and

co-opt

the labor of non-elites

by appearing

to

be

generous

in their distribution of

large

amounts

of food and drink. Lau sees this

pattern

as

part

of

broader

"leadership

innovations ... and ... strate-

gies" during

the

Early

Intermediate

period through-

out the Andes

(Lau 2002:300).

Craft Consumption

and

Feasting

in

Early

Nasca

Based on the

foregoing summary

of recent theo-

retical

developments regarding

crafts,

I

suggest

that

it is

equally

valuable to look at non-elite con-

sumption.

While demand from elites and non-elites

may

exist,

the

potential

for non-elites to obtain

finely

crafted

goods

in

middle-range

societies can

be

problematic.

One

way

non-elites can obtain them

is

through feasting

ceremonies,

a social arena in

which elites

display

and distribute

highly

valued

crafts

(such

as

polychrome pottery)

to simultane-

ously

enhance their own status while

engendering

group solidarity.

In the

Andes, feasting

was an activ-

ity

that elites could use to create

reciprocal oblig-

ations and social debt

very early

in

prehistory.

It is in this theoretical context that I examine the

apparent paradox

that exists between the

produc-

tion and

consumption

of

Early

Nasca

polychrome

pottery,

which

according

to recent research was

produced

in restricted contexts

yet

distributed

widely

to all

segments

of

society.

I focus on

Early

Nasca craft

consumption by determining

the

degree

to which

polychromes

were consumed

by

non-

elites. If consumed as

previously assumed, can we

account for this non-elite

consumption

in the

broader theoretical context of crafts, feasting,

and

middle-range

societies outlined above?

To evaluate non-elite craft

consumption,

atten-

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 65

tion should first turn to residential

villages

where

the

majority

of non-elites lived in

prehispanic

Andean societies. I therefore shift to a discussion

of the

village approach,

and to evaluate

degrees

of

status differentiation within the Andean

village,

I

focus on households.

Elites, Non-Elites,

and Households

in Andean

Villages

Until

recently,

the

study

of

prehispanic

Andean

societies has been characterized

by

an

emphasis

on

urban sites and ceremonial centers-what could be

referred to as the

"temples-and-tombs" approach

(Schreiber 1999:162). Indeed,

as Schreiber indi-

cates,

the

emphasis

on

larger,

more

spectacular

archaeological

sites has come at the

expense

of

understanding

smaller,

humbler

settlements,

which

make

up

the

largest portion

of Andean societies. In

order to evaluate this

segment

of

society,

archae-

ologists,

like all social

scientists,

must

employ

a

variety

of

interpretive

scales to build

satisfactory

models

(Smith 1993).

One

approach,

referred to as

the

"village" approach (Vaughn 2000),

also the

"local

perspective" (Bermann 1994),

the "com-

munity" perspective (Kolb

and Snead

1997),

and

"rural

archaeology" (Schwartz

and Falconer

1994),

focuses on

single

communities. While the

village

approach

does not

ignore patterns

of

change

at a

regional

level,

it assumes that

analyzing

smaller set-

tlements is a

profitable

means of

evaluating pre-

historic societies. Because a

village

or

community

has its own

sociopolitical

order,

economic

patterns,

and historical

trajectories,

often

very

different from

that witnessed at other

scales,

the

village approach

necessarily complements regional analyses

and

provides relatively fine-grained perspectives

on

social and economic

organization

that

regional

approaches

cannot

provide.

Furthermore,

the

means

by

which the

village

articulates with other

segments

of

society (such

as the civic-ceremonial

center,

regional

center, etc.)

is

key

to understand-

ing

that

society.

More

importantly,

if we are to

understand the movement of

goods

from

produc-

tion to

consumption

in

prehispanic societies, we

must focus on where those

goods

were

actually

consumed.

Regardless

of the name of the

approach,

an

archaeological

research

program

that focuses on a

smaller level of

analysis

than the

region-one

that

evaluates a

single village-must

have a

primary

unit of

analysis. Although

some of the above

approaches employ

the entire

community

as the

unit of

analysis (e.g.,

Kolb and Snead

1997),

house-

holds are more

frequently targeted.

Ethnographic

and ethnohistoric evidence

sug-

gests

that the nuclear

family

household was an

important

economic unit in

prehispanic

Andean

societies

(Aldenderfer

and Stanish

1993;

Stanish

1989:8, 1992:18).

Households are the

primary pro-

ductive, consumptive,

and

exchange

units in ethno-

graphic examples

of Andean societies. As the

principal

economic

unit,

the household is the most

useful

analytical

tool for

evaluating sociopolitical

and economic

relationships

within

archaeological

settlements

(Stanish 1989:7).

One

primary advantage

of "household archae-

ology"

is that status differences within a

village

can

be evaluated

(Bermann 1997;

Blanton

1995;

Hirth

1993; Santley

and Hirth

1993;

Stanish

1989, 1992;

van

Gij seghem 2001). Following

this

approach,

we

would

expect

status differences within a commu-

nity

to be manifested in one or more of the fol-

lowing ways: (1)

There

may

be households that are

larger

than others.

Ethnographically

and ethnohis-

torically,

individuals of

higher

rank tend to have

larger

households than those of lower rank

(Cou-

pland

and

Banning

1996;

Hirth

1993:123; Netting

1982), resulting

in much

larger physical

structures.

(2)

There

may

be structures that contain a

variety

of

specialized

architectural

features,

are subdivided

into

public

and

private space,

or involve a

greater

labor investment in construction

(Abrams

1989;

Hirth

1993:124). (3)

There

may

be structures whose

artifact

assemblage

contains

goods

of

higher

value,

and more items overall because

higher-status

households can

potentially

consume

relatively

more while

producing

less

(Hirth 1993;

Smith

1987;

Wilk and Ashmore

1988:124).

Valuable

goods

can be in the form of

"exotics,"

products

requiring higher

labor

investments,

or items with

significant

ritual or cultural value that

may

not nec-

essarily

be related to distant sources or

high

labor

investment. These three

expectations

serve as indi-

cators of either individuals, families, or households

of

higher

status (Hirth 1993:123).

Household

Craft Consumption

in Nasca

To evaluate the dimensions of elite and non-elite

craft

consumption,

I focus on

Early

Intermediate

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

[Vol. 15,

No.

1,

2004

Ica

Palpa

Rfo Grande

Ingenio

Nasca

Cahuachi N

0 50 km

Figure

1.

Map

of the Nasca

region

with the Southern Nasca

Region (SNR) highlighted (after

Schreiber and Lancho

1995:Figure 1).

period

Nasca

society.

The Nasca culture

developed

a craft

economy

of

finely

made

polychrome

ceram-

ics

early

in its

history,

and

preliminary

observations

indicate that these

ceramics,

although

made in

restricted

contexts,

were distributed

widely

and

consumed

by many

social

groups. Therefore,

Nasca

provides

the

opportunity

to evaluate

archaeologi-

cal

assumptions

about the role crafts

played

in mid-

dle-range

societies. While Nasca

appears

to have

lacked institutionalized

inequalities

in the form of

stratification,

forms of rank were

clearly present

(Carmichael 1988, 1995).

These

inequalities

were

manifested in differential

burials,

suggesting

that

certain members of Nasca

society

were ranked

above

others; however,

the

degree

of differentia-

tion,

which Carmichael refers to as a "status con-

tinuum"

(1995:175),

has not been evaluated in local

communities.

Archaeological

Context

The

prehispanic

Nasca culture

(ca.

A.D.

1-750)

developed

in an area of the south coast of Peru

defined

by

the Ica and Grande

drainages

and their

tributaries

(Figure 1).

The Nasca

region,

as it is

commonly

referred to

(Carmichael 1998),

is

extremely dry

and is delineated

by

the Andean

foothills to the

east,

the Pacific Ocean to the

west,

the Ica River

valley

in the

north,

and the Las Tran-

cas River

valley

in the south. Discussion focuses

on the Southern Nasca

Region (hereafter SNR)

defined

by

the

Aja,

Tierras Blancas

(which together

converge

in the modem town of Nasca to form the

Nasca

River), Taruga,

and Las Trancas river val-

leys (Schreiber

and Lancho

1995;

Vaughn 2000).

Ecologically,

the

region

is defined as

pre-montane

desert formation

(ONERN 1971).

The rivers that

run

through

the

valleys, only intermittently

filled

with

water,

are classified as "influent streams"

(ONERN 1971;

Schreiber and Lancho

1995).

Despite

the somewhat

marginal

nature of the

influent streams and the desert

environment,

in the

early part

of Nasca's

development,

the flooded

rivers

appear

to have

provided enough

water to

nourish

crops

on an annual basis

(Rowe 1963).

Indeed,

an alliance of chiefdoms based on a mixed

agro-pastoral economy

flourished in the

region

dur-

ing

most of the

Early

Intermediate

period (ca.

A.D.

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 67

Table 1. Peruvian and Nasca

Chronology. (After

Carmichael

1998;

Conlee 2000, 2003;

Schreiber 1998:Table A-1).

Horizons and Intermediate Periods Culture Nasca Phases

Approximate

Dates

Late Horizon Inka A.D. 1476

-

1532

Late Intermediate Period Tiza A.D. 1000

- 1476

Middle Horizon

Loro, Wari A.D. 750 - 1000

Early

Intermediate Period Late Nasca

6,7

A.D. 550 - 750

Middle Nasca 5 A.D. 450 - 550

Early

Nasca

2, 3,

4 A.D. 1-450

Early

Horizon Proto Nasca 1 100 B.C.

-

A.D. 1

Paracas 800 - 100 B.C.

Initial Period 1800

-

800 B.C.

Archaic 9000 -1800 B.C.

1-750;

Table

1).

The Nasca

chronological sequence

is divided into

Early

Nasca

(phases 2-4),'

Middle

Nasca

(phase 5),

and Late Nasca

(phases

6 and

7)

cultures

(Carmichael 1998;

Schreiber and Lancho

1995;

also see Silverman and Proulx

2002).

Recent research has demonstrated that Nasca

was a

loosely

allied

"confederacy" (Silverman

1993;

Silverman and Proulx

2002)

of chiefdoms

with a mixed

agropastoral

economic base

(Vaughn

2000). Sociopolitical leadership

did not

appear

to

be

highly

centralized in

Early

Nasca

society

(though

see Reindel and Isla

1998, 20012). Instead,

status was

probably negotiated, highly

flexible,

and

involved

political

acts and status

display

at

regional

ceremonial centers such as

Cahuachi,

certainly

the

most

important

of these centers

(see below;

Sil-

verman and Proulx

2002:244).

Pottery, Fertility,

and

Early

Nasca

Feasting

Polychrome Pottery.

One of the most

impressive

artifact classes of

Nasca,

indeed one that has

given

the

prehispanic

culture worldwide

fame,

is its

poly-

chrome

pottery.

Since their

"discovery" early

in the

twentieth

century,

Nasca

polychromes

were rec-

ognized

for their

quality (Uhle 1914). They

have

very

thin vessel walls

(Carmichael 1990:34;

Proulx

1968), up

to 15 distinct mineral-based

slip

colors

(Proulx 1968:25),

a wide

range

of vessel

shapes,

and

compelling iconography featuring

natural and

supernatural

motifs. The manufacture and

painting

of

polychromes

took a

great

deal of technical skill

(Carmichael 1990, 1998:224),

and it is reasonable

to assume that

they represent specialized

craft

pro-

duction. The

intensity, context, concentration,

and

scale of that

specialization (e.g.,

Costin

1991;

Costin and

Hagstrum 1995)

have

yet

to be

fully

defined.

However,

the

degree

of skill

required

in

their manufacture

suggests they

were not made

by

everyone

in

society (Vaughn

and Neff

2000).

Indeed,

an instrumental neutron activation

analy-

sis of a

sample

of

polychromes

from

Marcaya,

an

Early

Nasca

village (see below),

has indicated

pro-

ductive

specialization, given

the

pottery's compo-

sitional

uniformity

when

compared

to

plain

utilitarian wares

(Vaughn

and Neff

2000).

Agricultural Fertility.

Nasca

iconography

is well

known

(Carmichael 1992b, 1994;

Kroeber

1956;

Kroeber and Collier

1998;

Proulx

1968, 1983,

1994, 2000;

Roark

1965;

Sawyer

1961, 1966;

Townsend

1985;

Uhle

1914),

and is

generally

con-

sidered to be Nasca's

"principal purveyor

of ide-

ology" (Carmichael 1998:224). Agricultural

fertility

is the

prevailing

theme

conveyed

on Nasca

pottery (Carmichael 1992b, 1994;

see also Proulx

2000;

Silverman and Proulx

2002),

and for

Carmichael

(1998:224),

"the entire

corpus

of Nasca

iconography

is a

sacred,

interrelated visual

system

with its referents tied to the

dominating

themes of

water and

propagation."

Given the

marginal

envi-

ronment of the Nasca

region,

this

preoccupation

with water and

agricultural fertility

is not

surpris-

ing.

In

fact,

the

body

of

iconography depicted

on

polychromes

was

only

one of several cultural fea-

tures left

by

the

people

of Nasca that

speak

to their

concern with

growth, fertility,

and water.

For

example,

the famous Nasca

geoglyphs

(Nasca Lines)

have been

argued

to be an

integral

part

of the

worship

of mountain

gods

who con-

trolled

meteorological phenomena

such as

clouds,

lightning,

and most

importantly,

rain in traditional

Andean belief

systems (Reinhard 1988:365).

The

geoglyphs

themselves were

mostly

related to reli-

gious practices designed

to ensure that water would

be

provided

for

people

and their

crops (Reinhard

1988). Furthermore, disembodied,

or

trophy,

heads

are seen

contextually

as

having

a

symbolic

link to

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 15,

No.

1,

2004

fertility (Carmichael 1992b;

DeLeonardis

2000).

For

example,

the

"Sprouting

Head" motif found on

Nasca

polychromes,

in which

plants grow directly

out of

trophy

heads,

is seen to

represent

a direct

link between disembodied heads and

agricultural

fertility (Carmichael 1992b). Additionally,

disem-

bodied heads are seen as

part

of the "life to death

continuum"

(Carmichael 1992b)

in which the blood

from

decapitated

heads was

necessary

for human

and

plant fecundity (Allen 1981).

Early

Nasca

Feasting. Iconographic

evidence

also

suggests

that

large, group-oriented

ceremonies

involving feasting

were

integral

to Nasca life. For

example,

Carmichael

(1998:224, Figure 13)

observes that a scene

depicted

on a

double-spout

bottle

provides iconographic

evidence for

pottery

used in ceremonial and

feasting

contexts. The scene

depicts

a "central

deity" holding

a

panpipe,

sur-

rounded

by

ceramic

vessels,

and

people playing

panpipes

and

trumpets.

Carmichael

suggests

that

this bottle

may depict

a "festival in its

early stages"

(Carmichael 1998:224). Likewise,

Townsend

(1985:125, Figure 7)

has

reported

a

flaring

bowl

depicting

what he

interprets

to be an

agricultural

ceremony.

In Townsend's

interpretation,

the artist

"intended to

represent

a costumed

figure

such as

those who

appeared

in the

public plazas,

and

per-

haps

also in

agricultural

fields,

to celebrate the

great

annual feasts of the Nazca

region" (Townsend

1985:125).

It is

very likely

that

many

of these

"great

annual feasts" were carried out at

Cahuachi,

the

principal

ceremonial center of

Early

Nasca culture.

During Early

Nasca

times,

Cahuachi was the

focus of

pilgrimages

and

ceremony (Silverman

1993, 2002;

Silverman and Proulx

2002).

Excava-

tions conducted at the site

(Silverman 1993)

have

demonstrated that Cahuachi was not an urban cen-

ter in the traditional

archaeological

sense of the

word

(based

on Old World models of urbaniza-

tion),

but rather an Andean ceremonial center

(e.g.,

Rowe

1963).

The evidence for the ceremonial

nature of Cahuachi includes its numerous

temple

mounds and other structures

(Silverman 1993:310),

the ceremonial contexts found in excavations and

surface

analysis (Silverman 1993; Valdez 1994),

and the sacred burial

grounds

located at the site (Sil-

verman 1993; see also Silverman and Proulx 2002).

By

virtue of its ceremonial nature, Cahuachi is

believed to be a

place

where

pilgrims

from

through-

out the south coast

occasionally congregated

to

participate

in rites of intensification.

Many

of the

group

ceremonies conducted at the site involved

feasting (see

Silverman

1993;

Silverman and

Proulx

2002:132; Strong

1957:31;

Valdez

1994).

These ceremonial feasts at Cahuachi were "not

just

religious

acts.

They

were

political

acts clothed in

ritual and

embodying

Nasca

ideology" (Silverman

and Proulx

2002:244). Integral

to the

feasting

con-

text were the vessels in which food and drink was

served.

Clearly,

the most

commonly

used vessels

were the well-known

polychromes,

as few other

vessels

appropriate

for

serving

have been found in

excavations at Cahuachi

(Silverman 1993).

Cahuachi was not

just

an

important pilgrimage

center and a site of ritual

feasting,

but was also the

location of

polychrome production. Previously,

it

was

proposed

that an excess of

polychrome pot-

tery

was

produced

at Cahuachi and distributed to

groups making pilgrimages

to the site

(Vaughn

and

Neff

2000).

Given the current evidence of artifacts

related to

pottery production

(see Vaughn

and Neff

2000:88 for a

summary),

and a

compositional study

suggesting

a restricted locus of

polychrome pro-

duction,

it is clear that some

pottery

was

produced

at the ceremonial center

(see

Silverman

1993:277,

Figure 19.9), though

it is still unclear how much.

The Domestic Context

of

Nasca

Polychrome

Consumption

Paradoxically, although

Nasca

polychromes

are

very finely

made and have restricted

production

contexts,

they

were

apparently

used

by

all mem-

bers of Nasca

society.

For

example,

Carmichael has

suggested

that

"(t)he (Nasca)

ceramic

complex

was

an

open

shared

system

to which all members of

society

had access"

(Carmichael 1995:171).

Carmichael's conclusion was based on observa-

tions that fine

specimens analyzed

from burials

show evidence of use-wear

prior

to

being

interred

in

tombs,

and that most vessel

types

were available

to

people regardless

of their status.

Additionally,

researchers

working

on the south coast of Peru have

noted that Nasca habitation sites are covered with

the

fragmented

remains of

polychrome pottery

(Carmichael 1998:222; Silverman and Proulx

2002), implying

that the ceramics were used in

domestic as well as ceremonial contexts, and

per-

haps

even moved between these contexts.

The

apparent

extensive distribution of

poly-

chromes

throughout

the south coast of Peru led

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 69

some

early

researchers to

suggest

that Nasca was

an

expansive

state

extending

from the Pisco to the

Acari

valleys

and centered at Cahuachi

(Rowe

1963:304; Strong 1957).

Recent research indicates

instead that outside of the Ica and Grande

drainages,

polychromes

are

present

to a limited extent in elite

contexts,

and

suggests status-building

efforts

by

local elites who associated themselves with distant

powers (Carmichael 1992a;

Goldstein

2000;

Sil-

verman

1997;

Valdez

1998),

and

specifically

with

those

powers

associated with Cahuachi

(see

Valdez

1998).

These statements have remained untested

because

securely

excavated domestic contexts have

been

lacking

within the Nasca heartland.

Many

studies have

analyzed

ceramics recovered from

graves (Kroeber 1956;

Kroeber and Collier

1998;

Proulx

1968;

Tello

1917;

Uhle

1914); however,

there are few

examples

of excavated

polychrome

pottery

outside of

cemetery

contexts. These come

from excavations at

Cahuachi,

Pueblo

Viejo (Isla

et al.

1984),

and

recently,

Los Molinos and La

Mufia,

two

large

ceremonial sites

investigated by

Reindel and Isla

(1998, 2001). Therefore,

patterns

of Nasca

pottery

use in the domestic context are

unknown. In an

early study

of Nasca

iconography,

Catherine Allen

suggested

that,

"We

may guess-

from their

fineness,

apparently impractical

vessel

shapes,

and

good preservation-that

Nasca ceram-

ics were reserved for ritual

uses,

but

beyond

this

speculation

the

living

context of their use is forever

lost to us"

(1981:45-46).

How, then,

are we to understand the

apparent

wide distribution and

consumption

of Nasca

poly-

chromes? How were

they incorporated

into the "liv-

ing

context?" That

is,

how were

they

used and in

what contexts? What relation did the

consumption

of

polychromes

at habitations have to the con-

sumption

of

polychromes

in ceremonial contexts

such as those at Cahuachi? One method for address-

ing

these

questions

was to turn attention to a

pre-

hispanic

Nasca

village.

Given statements

by

previous

researchers,

we would

expect

a

high

con-

sumption

of

polychromes among

all social

groups

in the domestic context. Given the nature of status

differences at residential sites, however (Goldstein

2000:336), we

might

also

expect

a difference in the

quantities

of

polychromes

consumed and the kinds

of

polychromes

consumed between

high-status

and

low status

groups.

To address these

questions,

as

part

of a

larger

research

program investigating

the

domestic context of

Early

Nasca

society,

excava-

tions were conducted at the small

village

site,

Mar-

caya.

Marcaya

Marcaya

is

approximately

1

ha in size and is located

in the

Yunga ecological

zone of the Andean

foothills.

Lying

16 km

upstream

from the

modern

town of

Nasca,

at an elevation of

1,000

m above

sea

level,

the site is situated on the northern hill-

side of the Tierras Blancas River

valley

on a

gen-

tly sloping

colluvial fan

just

southeast of Cerro

Pongo

Chico

(Figure 2).

Surface Analysis

Because of a lack of

deposition,

structure founda-

tions remain visible on the surface of the site

today

and bear a

strong

resemblance to

previously

recorded

early

Nasca architecture

(Schreiber 1988;

Schreiber and Isla

1996).

The site consists of over

70 structures concentrated in three

separate

loci

(Figure 3).

Two basic

types

of structures were

recorded: houses and

patios.

Houses are small and

round,

generally

between 3 and 5 m in

diameter,

with walls

composed

of unworked and dressed

fieldstone set in mud mortar. The walls were

orig-

inally

between I and 1.5

m

in

height.

Doors in the

house walls led to attached

patios, larger

ovoid

structures

up

to 14 m in

length.

Houses and

patios

formed

contiguous

structure clusters referred to as

patio groups.

A number of undefined structures

were also recorded. These structures were isolated

and had little evidence for domestic

occupation.

They may

be ancient

corrals, though

this remains

to be determined

through

further

testing.

Twenty-three patio groups

were recorded

through

surface

analysis

and

mapping.

On the sur-

face,

the recorded

patio groups appeared

to be

archaeological

households

using

the three criteria

outlined

by

Stanish for

recognizing

households in

the

archaeological

record

(Stanish 1989, 1992).

That is,

they

were (1) distinct structure

groups

that

were (2) repeated throughout

the site, and (3) con-

tained the material remains of domestic activities.

The

goal

of the excavations was to obtain infor-

mation on socioeconomic activities that took

place

in the

patio groups, including

the nature of

poly-

chrome

consumption,

and status differences at the

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

[Vol. 15,

No.

1,

2004

V

V

0

//o

0 Volischo

Of~ " Tururugi

cat

ya rande

-,00

Marca a

Ata' nco

00

alO

01800

Cerro

Marcaya

0

MinaSol de Oro

Cerro Pt

la1,0

400~ n

i1

kilorneter

Figure

2.

Map

of the immediate surroundings

of

Marcaya.

site,

including

differences in

polychrome

con-

sumption

between identified

patio groups.

A surface

analysis

was undertaken to determine

the

variability

in household size and labor invest-

ment

present

at

Marcaya.

In the surface

inspection,

the size of

patio groups,

the

presence

of internal

architectural

features,

and the

quality

of architec-

ture were recorded. Based on overall

dimensions,

patio groups

were defined as either small or

large,

with

patio groups

over

90

m2 defined as

large.

Inter-

nal features and architectural

spaces

visible on the

surface were also recorded.

Internally

defined

spaces

within houses and

patios

were

very

rare and

found in

only

three

patio groups. Finally,

the vari-

ability

in architectural

quality

was recorded. While

in most

houses,

walls were constructed

using

sim-

ple

fieldstone and mud

mortar,

in some

houses,

an

effort was made to delineate well-defined interior

spaces by using partially

dressed field stone with

smooth,

flat sides. Architectural differences were

also manifested in the construction of house doors.

Doors were made

by

either

leaving

a

gap

in the wall

construction or were framed

by

two dressed stones

placed vertically

on either side of the

gap.

In

short,

with

regards

to surface evidence of sta-

tus differences there were four criteria that differ-

entiated households:

(1)

size of the

patio group, (2)

presence

of internal architectural

features, (3) pres-

ence of worked stone in wall

architecture,

and

(4)

presence

of worked stone in the doors of houses.

Only

three

patio groups

at

Marcaya

met all four of

these criteria:

X, XII,

and XV

and,

based on these

surface

differences, they

were defined as

high-sta-

tus households

(Table 2;

see

Figure 4).

Household Excavations at

Marcaya

A

judgmental sampling strategy

was chosen to

attain excavation data that would

permit

evaluation

of the differences between

high-

and low-status

households. Excavations were conducted within

eight

different

patio groups (as

well as ten isolated

structures),

of which two were

high

status and six

were low status

(Figure 4).

The most common features encountered in exca-

vations were those related to food

processing,

preparation,

and

storage (Figures

5 and

6).

Each of

the

patio groups

excavated contained artifacts and

features related to these

activities,

though

the iden-

tified features and

quantity

of material recovered

varied from one

patio group

to another. Hearths

were found in numerous structures

including

both

houses and

patios,

and

large

batanes

(grinding

stones)

and

chungas (rockers)

were recovered as

well. Excavation and surface

analysis (as many

were

exposed

on the

surface)

revealed stone-lined

pits

in

virtually every

structure

(Figure 7).

Local

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 71

/

: Marcaya

-Tocus

2/

.

-

architecture

-.

modern road

_ _ 2m contour

Locus10 meters

0

f,

!1:'.'

f '--'

'-'

'-'

2:-

?

..

-'

....

Figure

3.

Topographic map

of

Marcaya.

Based on surface

analysis,

the site was divided into three

principal

loci. Two

high

status

patio groups (X

and

XII)

are indicated.

informants indicated that modem features similar

to these were referred to in recent times as collo-

mas,

and this term was

adopted

for the

prehispanic

features.3

Aside from the

processing

and

storage

of sub-

sistence-related

goods,

material correlates of other

domestic activities were found. Most

patio groups

produced

some evidence for lithic

production using

local raw materials and obsidian from the

Quispi-

sisa source

(Vaughn

and Glascock

2004).

One

patio

group (V) appears

to be a small lithic

workshop.

Additionally,

residents of each household were

involved in

weaving.

Whole and

fragmented spin-

dle whorls were recovered in most

patio groups.

Analysis

of the size and

weight

of the

spindle

whorls

suggests they

were used to

spin

camelid

wool

(Vaughn 2000).

Economic activities at

Marcaya appear

to have

been

predominantly organized by

the household.

Archaeological

correlates for economic activities

found in each

patio group suggest

that households

were the

primary

economic unit at

Marcaya

and

each was

economically independent,

as each

patio

group

was

functionally

redundant and had the com-

ponents

to sustain a domestic unit. All households

contained evidence for food

storage

and

process-

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

[Vol. 15,

No. 1, 2004

Table 2. Various Measures of Status from Surface

Analysis

and Excavations

Suggest

That Two Patio

Groups,

X and

XII,

at

Marcaya

are

Noticeably

Different.

Worked Worked Status Based

Patio Area Stone Stone Internal on Surface

Polychrome Panpipe

Groups (m2)

Size Walls Door Architecture

Analysis

Index Index

I

? ? y y

n low 36.67 0.00

II

34.5 small n

y

n low n/aa n/a

III 16.4 small n n n low n/a n/a

IV 54.6 small

y y

n low n/a n/a

V 128.0

large y y

n low 32.16 0.00

VI 30.9 small n n n low n/a n/a

VII ? ? n

y

n low n/a n/a

VIII 145.5

large y y

n low 33.33 0.00

IX

57.6 small n

y

n low n/a n/a

X 126.9

large y y y high

143.88 0.75

XI 91.8

large

n n n low 97.57 0.19

XII

95.9

large y y y high

130.7 0.68

XIII 63.7 small

y y

n low n/a n/a

XIV ? ?

y y

n low 128.00 1.00

XV 112.0

large y y y high

n/a n/a

XVI 54.0 small

y y

n low n/a n/a

XVII 44.2 small

y y

n low n/a n/a

XVIII 66.6 small

y y

n low n/a n/a

XIX 32.2 small n

y

n low n/a n/a

XX 26.8 small n n n low n/a n/a

XXI 57.0 small n

y

n low n/a n/a

XXII 71.5 small n

y

n low 32.22 0.00

XXIII 25.8 small n n n low n/a n/a

Indices were calculated

by dividing

the

weight

of the artifact

type by

the total cubic meters

excavated, resulting

in a stan-

dardized measure for each

patio group.

Note that Patio

Group

XV was not excavated.

ing, cooking,

and

consumption. Collomas,

the

only

known

storage

facilities at

Marcaya,

were found

without

exception,

either within the confines of

patios

and houses or in

closely

associated

patio

groups.

No evidence for communal

storage,

food

processing,

or other activities were revealed.

An

exception

to the

self-sufficiency

of house-

holds was that none

appeared

to

produce pottery.

Indeed,

firing

loci,

caches of

clay, wasters,

and

other

manufacturing

evidence were not found in

fieldwork.

Additionally, spindle

whorls were made

by

the rather laborious

process

of

modifying

bro-

ken wall sherds from

large storage vessels,

pro-

viding evidence,

albeit

indirect,

that ceramics were

not made at the site.

Ceramics recovered within all

patio groups

fell

into the Nasca 3 and Nasca 4

phases (e.g.,

Proulx

1968),

and radiocarbon dates from charcoal sam-

ples span

a

relatively

short

period

of time

(Table

3). Although

when two standard deviations are

taken into

consideration,

the

occupation

of the site

could

encompass

several

centuries,

all three radio-

carbon dates

overlap

within the end of the fourth

and the

beginning

of the fifth centuries

A.D.,

specif-

ically

A.D.

370-420,

suggesting

that this interval

may

have been the

primary occupation

of the site.

Overall,

the shallow

deposits,

the

relatively

restricted

phases

of the

pottery,

as well as the radio-

carbon dates

suggest

a short

occupation

at

Marcaya.

Though

fieldwork did not reveal evidence for

its

manufacture,

pottery

was the most

ubiquitous

artifact. The

pottery

included what was defined as

utilitarian ware

(wall

thickness 6 mm or

more)

and

fine ware

(wall

thickness less than 6

mm).

This arbi-

trary

classification

separated

the vessel

assemblage

into two basic

categories: painted polychrome pot-

tery

and

plain

utilitarian

pottery.

This classification

encompassed

all vessel

types

except

for one. The

exception

was a

type

of

glob-

ularjar simply

decorated with

wide,

wavy,

maroon

lines on a white or buff

background

with black out-

line.

Strong (1957:Figure 12) originally

referred to

this

design

as Cahuachi Broad Line

Red, White,

and

Black,

and others have followed

(Silverman

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughn]

EARLY NASCA CRAFT CONSUMPTION 73

Sxx

,xxi

XX0

XIX

Site Datum

Test Unit 1

XVIIXV

XXIIIll

X

,

XV

XVI

IV

X

XII

XIII

o C

CVL

,VIII

VII

-

VI

IV

..)

-

III

Excavated structure

N

Structure excavated

with test trench

10t m1eters

Figure

4. Excavated structures at

Marcaya.

Dashed lines indicate

patio groups

as

designated

in the field.

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 25 Mar 2013 07:53:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

[Vol. 15,

No.

1,2004

Patio

Group

XII

SHigh

artifact concentration

t

Deflated

N 2m

Colloma

Deflated

Sub-Datum B

+ a

Colloma

Hearth

Batan

Deflated

SAsh

ump

ola

Storage pit

Headja

Structure 29

x1

Roof supports

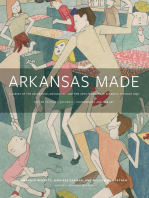

Figure

5. Excavations in Patio

Group XII.

1993).

In

published

literature,

this

design

is

only

present

on a

particular

vessel

form,

referred to as

Three-Handled

Jars

(shape TIT) (Kroeber

and Col-

lier

1998:Figures 90, 128, 155,

and

187;

Proulx

1970:64 and Plate

12E).

I refer to these

jars

sim-

ply

as

"painted jars" (Vaughn

and Neff

2000),

and

the term refers

specifically

to these three-handled

jars

with the Cahuachi Broad Line

Red, White,

and

Black

design.

Painted

jars

are an

exception

to the

dichotomy

between utilitarian ware and fine ware

because

they

are

painted (although

sometimes

crudely)

but have

very

thick walls. In this

paper,

these

painted jars

are referred to as utilitarian wares

because of their wall thickness.

Both utilitarian and fine wares were found in all

excavated contexts

(Figures

8 and

9).

When the

MNI

indicator is used4 the

proportion

of fine ware

vessels at

Marcaya

amounts to 55

percent

of the

total vessel

assemblage (Table 4). Compositional

analysis

of the

pottery through

neutron activation

demonstrated that the

composition

of the

utilitat-

ian wares varied while the fine wares were com-

positionally homogeneous, strongly suggesting

that

although they

were not

produced

at the

site,

poly-

chrome

pottery

was

produced

in a concentrated

context

(Vaughn