Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Chua Cheong Gould 2012

Cargado por

faris_hibaturDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Chua Cheong Gould 2012

Cargado por

faris_hibaturCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTING RESEARCH American Accounting Association

Vol. 11, No. 1 DOI: 10.2308/jiar-10212

2012

pp. 119146

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on

Accounting Quality: Evidence from Australia

Yi Lin (Elaine) Chua, Chee Seng Cheong, and Graeme Gould

ABSTRACT: Following the mandatory implementation of International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS) in Australia as of January 1, 2005, this study examines

its impact on accounting quality by focusing on three perspectives: (1) earnings

management, (2) timely loss recognition, and (3) value relevance. Using four years of

adoption experience since the mandate was first made effective in Australia for a wide

range of accounting-based metrics and market-based information, we find that the

mandatory adoption of IFRS has resulted in better accounting quality than previously

under Australian generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). In particular, the

findings indicate that the pervasiveness of earnings management by way of smoothing

has reduced, while the timeliness of loss recognition has improved post-adoption.

Additionally, the value relevance of financial statement information has improved,

especially for non-financial firms. This is despite the fact that there is evidence to suggest

that financial firms are engaged in managing earnings toward a small positive target after

the mandatory adoption of IFRS in Australia.

Keywords: IFRS; accounting quality; international accounting; Australia.

I. INTRODUCTION

I

n 2002, Australia and the European Union (EU) formalized their decision to adopt

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) mandatorily as of January 1, 2005 (FRC

2002; Armstrong et al. 2010). Even though IFRS

1

have been developed by the International

Accounting Standards Board (IASB) for a notably long period,

2

these events marked the beginning

Yi Lin (Elaine) Chua is an Associate Lecturer, Chee Seng Cheong is a Senior Lecturer, and Graeme Gould is a

Lecturer, all at the University of Adelaide.

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable comments of Ervin Black (editor), Nabil Elias (discussant), Jim Larkin, Grant

Richardson, two anonymous referees, and participants at the 2010 Journal of International Accounting Research

conference. All errors and omissions are our own.

Published Online: January 2012

1

For simplicity, the term IFRS is used in this paper to include both old and new versions of international

accounting standards (including IAS). This is consistent with the denition of IFRS as stated in IAS 1.11

(Deloitte 2009b).

2

This effort started in 1973 with the establishment of the IASBs predecessor, the International Accounting

Standards Committee (IASC). Standards issued by the IASC were known as International Accounting Standards

(IAS), and these standards were subsequently incorporated into IFRS in 2006, which resulted in a single set of

international accounting standards being used today (Ball 2006).

119

of the era of mandatory IFRS adoption by countries around the world. This has introduced a new

phase of interest in IFRS, as many global capital market participants are becoming increasingly

concerned whether accounting quality had been signicantly affected by the transition. To address

this question, we examine the association between IFRS adoption and accounting quality in the

context of the Australian capital market. Specically, earnings management, timely loss

recognition, and value relevance of accounting numbers are compared before and after the

mandatory introduction of IFRS in Australia to determine its effect on accounting quality.

3

As the adoption worldwide represents a major shift in the international nancial reporting

arena, empirical evidence on IFRS adoption has become more and more imperative in accounting

literature. In particular, much related research began by focusing on the determinants and

consequences of adopting IFRS voluntarily (e.g., Ashbaugh and Pincus 2001; Barth et al. 2008).

Based on these studies, improved accounting quality due to high-quality accounting standards and

enhanced comparability are among the benets claimed by proponents of IFRS adoption. However,

the inherent self-selection bias in the earlier research on voluntary IFRS adoption has prompted the

question whether the positive ndings can be generalized to those adopting rms in the mandatory

environment. In contrast to the traditional approach of adopting IFRS voluntarily, such as those

commonly found in Germany for example (Soderstrom and Sun 2007), more and more countries

are now following the footsteps of the forerunner countries, like Australia and the EU, to make the

adoption compulsory for rms in their countries.

4

As a consequence, these affected rms are

required to change to IFRS in compliance with the law and have little say about the resulting

impacts.

This study aims to exploit the unique features offered by the Australian adoption of IFRS and

to contribute to the literature examining the effects of adopting IFRS in several ways. First,

Australia is one of the rst countries located outside of the EU that has mandated the adoption of

IFRS. Therefore, we contribute to the existing literature that has largely focused on EU adoption

only. The ndings also provide more comparable evidence to other adopting countries, as their

adoption is not similarly motivated by the EU harmonization efforts

5

and so their degree of

adoption impacts can vary from those in the EU (Daske et al. 2008). Additionally, Australia is a

forerunner country in mandating the adoption of IFRS and so it has a comparatively longer

adoption experience relative to other countries that mandated the adoption post-2005. This allows a

sufcient information window to assess the impact of mandating the adoption, as the effects often

require time to materialize post-implementation. Finally, Australia is also the rst non-EU adopting

country that had fully prohibited an early adoption of IFRS prior to the 2005 mandate (Jeanjean and

Stolowy 2008). This provides a suitable setting to include only mandatory adopters in this study, as

the presence of voluntary adopters would create a self-selection bias to the ndings that needs to be

controlled for (see Leuz and Verrecchia 2000; Ashbaugh and Pincus 2001; Van Tendeloo and

Vanstraelen 2005; Covrig et al. 2007; Barth et al. 2008).

With a cumulative four years of adoption experience on-hand for Australia, we compare the

quality of accounting numbers under Australian GAAP and IFRS by using a wide range of

accounting-based metrics and market-based data. Consistent with prior research, the impact on

3

The research question focuses on the application of IFRS in the Australian context and therefore should

accurately refer to the Australian equivalent of IFRS (A-IFRS) and not IFRS per se. Given that both sets of

standards are almost identical in most cases, for simplicity IFRS is used throughout this paper.

4

Details about the adoption timetable for individual countries can be obtained from the IAS Plus website at http://

www.iasplus.com

5

The EUs harmonization efforts began in the 1970s and since then have involved a number of Accounting

Directives. Among them, the Fourth Directive requires all limited liability companies to prepare annual nancial

statements, while the Seventh Directive requires a parent company to prepare consolidated nancial statements

(Haller 2002; Jones and Higgins 2006; ICAEW 2007).

120 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

accounting quality is examined from three different perspectives (Lang et al. 2003; Lang et al.

2006; Barth et al. 2008; Christensen et al. 2008; Paananen and Lin 2009). First, we compare the

pervasiveness of earnings management under Australian GAAP and IFRS, by examining the extent

in which earnings are smoothed and managed toward a positive target. Second, we assess whether

the mandatory change in accounting standards has affected the timely loss recognition in the

Australian capital market. Third, we assess whether IFRS has led to a change in the value relevance

of accounting numbers produced by Australian rms. Based on this research design, we not only

take into account the uniqueness of the Australian adoption of IFRS, but also provide more robust

evidence than previous Australian studies that have only included a single metric and a limited

timeframe in examining the quality of accounting numbers under IFRS (see Goodwin et al. 2008a;

Jeanjean and Stolowy 2008). By limiting the investigation in Australia, we also aim to hold

constant the inuence of institutional factors in determining accounting quality to strengthen the

validity of our ndings.

Overall, inferences based on a sample of 1,376 rm-year observations for 172 Australian listed

rms provide support that the adoption of IFRS in Australia has made an improvement to

accounting quality. Specically, we nd evidence that following the mandatory adoption of IFRS,

Australian rms engage in less earnings management by way of income smoothing, better timely

loss recognition, and improvement in value relevance of accounting information.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the relevant

literature on the adoption of IFRS, which subsequently leads to the development of hypotheses. The

third section explains the research design and sample data employed in the study. The fourth section

presents the descriptive and empirical results, and we provide our conclusions in the nal section.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Consistent with the long-term objective of the IASB, IFRS purport to be a set of high-quality

accounting rules that would ideally be applied consistently by public companies globally to ensure

that they are acceptable by the capital markets around the world (IASB 2009). While there is no

consensus as to what constitutes high-quality accounting standards, IFRS are perceived to be high

quality because they represent a collection of the worlds best accounting practices and are

purported to be more capital-market-oriented than many domestic accounting standards

6

(Ding et

al. 2007). The principles-based nature of IFRS (Carmona and Trombetta 2008) also encourages

rms to report accounting information that better reects the economic substance over form and

therefore promotes greater transparency (Maines et al. 2003). Accordingly, it is posited that the

adoption of IFRS is associated with high accounting quality, and the research by Barth et al. (2008)

is a prominent paper in support of this view.

7

By using a sample of rms from 21 countries, Barth et

al. (2008) show that rms that adopted IFRS voluntarily exhibit less earnings management, more

timely loss recognition, and greater value relevance of accounting income. Together, these ndings

support the notion that the IFRS rms are of higher quality than those matched sample rms

applying non-U.S. local accounting standards. Furthermore, accounting quality is also found to

have improved after those adopting rms moved from local accounting standards to IFRS. Overall,

the research evidences that accounting quality, on average, has improved for voluntary IFRS

adopters around the world.

6

This contrasts from the stakeholders-oriented accounting standards traditionally found in code-law countries,

like Germany and France. It is argued by prior literature that the stakeholders-oriented standards are of lower

quality than the capital-market-oriented standards (Ball et al. 2003).

7

See also Bartov et al. (2005) in respect to the higher-value relevance of IFRS earnings over those under German

GAAP for the voluntary adoption in Germany.

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 121

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

Those in favor of IFRS adoption also argue that IFRS standards enhance comparability of

nancial statements across countries and markets, which is also a component of high-quality

nancial reporting (Pownall and Schipper 1999). By using the same accounting language in

preparing nancial statements across different countries, global investors and nancial analysts are

less likely to face interpretation difculties, thereby facilitating information ow between capital

markets and encouraging cross-border capital raisings.

8

Ashbaugh and Pincus (2001) nd that for

rms in 13 countries, analysts forecast accuracy increases after they voluntarily adopted IFRS.

Additionally, they also nd that forecast accuracy is negatively associated with the differences

between domestic accounting standards and IFRS. These ndings support the argument that by

eliminating many differences in accounting standards and standardizing the format of reporting

through the use of IFRS, analysts and investors can reduce the need to make adjustments when

comparing nancial statements internationally (Ball 2006), enabling them to better monitor and

evaluate the quality of nancial statements across rms (Jeanjean and Stolowy 2008; Daske et al.

2008). This potentially induces management to provide higher-quality information to users for their

decision making.

Despite the persuasive arguments that IFRS adoption enhances accounting quality and that some

evidence exists supporting the claims, there are also prior studies that suggest the contrary, especially

in the mandatory adoption environment. For instance, Paananen and Lin (2009) nd that the

development of IFRS had caused accounting quality to worsen over time. Specically, they nd that

German rms exhibit a fall in accounting quality after they adopted IFRS mandatorily. This is further

supported by Christensen et al. (2008), who nd consistent results analogous to Barth et al. (2008) for

voluntary adopting rms in Germany, but could not nd such improvements for German rms that

delayed their adoption until being mandated. Furthermore, Jeanjean and Stolowy (2008) nd that the

rst-time IFRS adopting rms in Australia and the U.K. showed relatively persistent earnings

management after the mandatory adoption of IFRS, while those in France showed an increase in

earnings management. In contrast to the positive results of earlier research on voluntary IFRS

adoption, these recent studies suggest that it is not appropriate to generalize the effects of adopting

IFRS from the previous voluntary adoption experience to the current mandatory environment.

Considering the mixed ndings for the impact of adopting IFRS on accounting quality,

distinguishing prior studies across voluntary and mandatory adopters thus rests on the inuence of

adopters incentive to utilize IFRS. Those voluntary IFRS adopters are said to have discretion to

choose the best disclosure rules (IFRS in this instance) that reduce information asymmetry with

principals (who are less informed) about future prospects of the rm and managers consumption of

perquisites

9

(Jensen and Meckling 1976), whereas rms in countries that mandated IFRS adoption

must now apply IFRS regardless of whether they consider this to be an economical decision. As a

result, several recent studies have considered reporting incentives to be a more dominant factor in

determining the observed accounting quality (Ball et al. 2003; Burghstahler et al. 2006; Soderstrom

and Sun 2007; Christensen et al. 2008). Therefore, the inherent self-selection bias in the earlier

research of voluntary IFRS adoption potentially overestimates the positive impact of adopting

IFRS, and the ndings cannot be generalized to the current trend of mandatory adoption without

caution.

8

The endorsement of the International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSCO) in 2000, which permits

companies to prepare IFRS-based accounts for cross-border offerings and listings in major capital markets, is

indicative that IFRS are acceptable for international investments and transactions (Haller 2002; Deloitte 2009a).

Similarly, Covrig et al. (2007) also nd that companies around the world attracted higher investments from

foreign mutual funds by adopting IFRS voluntarily instead of using domestic standards.

9

Each rm is expected to choose the best set of accounting standards based on their individual circumstances,

which may not necessarily result in the same set of accounting standards being used by all rms.

122 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

The mixed ndings documented by prior studies also highlight that the effect of adopting IFRS

on accounting quality could vary across different countries. This is because prior literature suggests

that countries institutional structures play an important role in determining accounting quality

through the countries legal and political systems (Burghstahler et al. 2006; Soderstrom and Sun

2007; Holthausen 2009). Specically, Daske et al. (2008) show that the incremental economic

benets following the mandatory IFRS adoption only occur in countries where rms have

incentives to be transparent and where legal enforcement is strong. This contradicts the proposition

that switching to IFRS does not provide much incremental benet to countries that have enjoyed

high-quality accounting standards and strong investor protection mechanisms. This is based on the

assumption that these countries would have better reporting practices prior to the introduction of

IFRS, all else equal, even if the presumption that high-quality accounting standards alone improve

rms reporting quality is valid (Jeanjean and Stolowy 2008). Having said that, many past studies

on IFRS adoption have particularly concentrated on the EU setting because of the large number of

countries involved (Armstrong et al. 2010) and the presence of many code-law countries in the EU

that facilitates a comparison of common-law and code-law standards (Christensen et al. 2008).

Nevertheless, it is difcult to generalize the ndings of these EU studies to non-EU adopting

countries, as harmonization efforts within the EU may have resulted in a signicantly larger impact

following the EU adoption than other non-EU adopting countries (Daske et al. 2008). Overall, there

is no clear evidence on how the implementation of IFRS impacts accounting quality for the growing

number of non-EU countries that have either mandated or are in the process of mandating the

adoption.

Hypotheses Development

In view of the conicting arguments and mixed ndings for the impact of adopting IFRS

mandatorily on accounting quality, the net effect for the Australian adoption of IFRS is therefore

uncertain. Although Australia began its mandatory adoption of IFRS from January 1, 2005,

Australian rms have had experience in using principles-based standards from the application of

Australian GAAP, which should be similarly applicable to the use of IFRS (Brown and Tarca

2005). This provides Australia with a potential competitive advantage over other adopting

countries, especially those code-law countries in the EU. Furthermore, the existence of a high-

quality national accounting regime in Australia and a well-regarded reputation for enforcement may

also imply that the country had already enjoyed high-quality reporting practices prior to the

introduction of IFRS

10

(La et al. 1998; Kaufmann et al. 2008; Haswell and McKinnon 2003;

Haswell and Langeld-Smith 2008). This favorable position is expected to allow Australian rms to

have a more manageable and smoother transition to IFRS, suggesting that the adoption is expected

to result in a smaller or negligible impact on the change in Australian accounting quality.

Taking into account the benets asserted by supporters of IFRS adoption and ndings of prior

research, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC)

11

of Australia claimed in 2002 that the adoption of

IFRS would improve the overall quality of nancial reporting in Australia (FRC 2002).

However, this view was not entirely supported by all commentators, academics, and the business

community. Specically, Haswell and McKinnon (2003) suggested that a change to IFRS could

possibly reduce the overall quality of nancial reports in Australia, which potentially contradicts the

10

There is no empirical evidence to suggest that Australia has experienced signicant institutional changes during

the sample period.

11

The FRC is an Australian government body responsible for providing broad oversight for the standards-setting

process in Australia. More details about this organization can be obtained from the FRC website at http://www.

frc.gov.au

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 123

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

objective of the Australian adoption of IFRS. The concern is also further exacerbated by the

ndings of several studies, which documented that Australian rms were not well prepared for the

transition to IFRS, even within months prior to the mandate date (see Muir 2004; Jones and Higgins

2006; Goodwin et al. 2008b). Moreover, some commentators still observed many notable

differences between Australian GAAP and IFRS (Howieson and Langeld-Smith 2003; Haswell

and McKinnon 2003; Haswell and Langeld-Smith 2008; Goodwin et al. 2008a), and that

implementation had also resulted in signicant costs to many adopting rms (PWC 2008). Given

the unsettling results about the preparedness of Australian rms on the adoption, there are some

doubts about the effectiveness of implementation following the adoption and its inuence on

decreasing accounting quality in Australia.

Two studies have directly examined the impact of the mandatory adoption of IFRS on

accounting quality in Australia. First, Goodwin et al. (2008a) investigate the effect of IFRS

adoption in Australia on both the accounts and value relevance, by examining the rst-time

reconciliations to IFRS provided in the rst annual accounts under IFRS. Despite nding that the

adoption of IFRS has resulted in signicant adjustments to accounting numbers and ratios, they nd

mixed ndings in terms of the value relevance of the IFRS numbers over those under Australian

GAAP, suggesting that nancial reporting quality has not been improved as claimed by the FRC. In

the other study, using earnings management as a proxy for accounting quality, Jeanjean and

Stolowy (2008) examine whether the adopting rms in Australia have managed their earnings to

avoid losses any less after the introduction of IFRS.

12

By analyzing the distributions of earnings

between 2002 and 2006, they nd that the pervasiveness of earnings management had not changed

in Australia. Although each of these two studies has assessed accounting quality from a different

perspective (value relevance and earnings management), both studies are subject to the same

limitation of relying on a single measure to investigate the multi-dimensional concept of accounting

quality. On top of that, both studies only focused on a short period of time after the implementation

of IFRS in Australia and so may not have allowed sufcient time for the effects of adoption to

materialize. To address these limitations, we therefore use multiple measures to proxy accounting

quality, as well as a longer information window than the existing literature.

On the whole, we predict that the mandatory implementation of IFRS had affected accounting

quality in Australia. Even though Australian rms are perceived to have a more superior position in

the changeover to IFRS, prior research has shown that the compulsory move from Australian

GAAP to IFRS still resulted in signicant adjustments to both the accounts and the transition

process (see Muir 2004; Jones and Higgins 2006; Goodwin et al. 2008a, 2008b). While earlier

studies on IFRS adoption provide support to the claim that accounting quality should improve

following the use of IFRS (e.g., Bartov et al. 2005; Barth et al. 2008), there are also several

instances where a negative impact has been found on accounting quality in the recent mandatory

environment (e.g., Christensen et al. 2008; Paananen and Lin 2009). As a consequence, these mixed

ndings do not provide us with a clear prediction about the impact on accounting quality in the

context of the Australian adoption of IFRS. On one hand, the mandatory introduction of IFRS in

Australia can be justied by the positive ndings of earlier research. The benet of improved

accounting quality following IFRS adoption is also likely to eventuate in the Australian

environment where both legal enforcement and investor protection are purported to be strong. On

the other hand, the recent studies have shown that mandating such a radical change in nancial

reporting is less likely to increase rms incentive to benet from IFRS adoption; thereby, this

potentially impedes the effective implementation of IFRS and hampers the existing high-quality

12

Apart from Australia, Jeanjean and Stolowy (2008) also include France and the U.K. in their study. The ndings

of this paper are discussed in the earlier section.

124 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

reporting practices in Australia. Furthermore, the well-regarded reputation for a high-quality

Australian accounting regime in the time preceding IFRS adoption is also likely to set a relatively

high benchmark for an improvement in accounting quality to materialize following the mandatory

change in Australia. Putting the aforementioned limitations aside, Goodwin et al. (2008a) and

Jeanjean and Stolowy (2008) show that accounting quality in terms of value relevance and earnings

management has not improved within the short timeframe after the mandatory implementation of

IFRS in Australia. If accounting quality has indeed been enhanced as a result of the mandatory

adoption of IFRS, then we should expect to nd less earnings management, more timely

recognition of losses, as well as higher value relevance of accounting numbers in Australia post-

adoption, or vice versa.

Taken together that we have no clear prediction about the direction of which accounting quality

had been affected by the mandatory adoption of IFRS in Australia, we therefore propose the

following research hypotheses:

H1: Earnings management has changed following the mandatory adoption of IFRS in

Australia.

H2: Timely loss recognition has changed following the mandatory adoption of IFRS in

Australia.

H3: The degree of association between accounting data and share price (i.e., value relevance)

has changed following the mandatory adoption of IFRS in Australia.

III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Sample and Dataset Selection

As stated earlier, we focus on the Australian capital market to analyze the impact of mandating

the adoption of IFRS. Table 1 presents the sample selection process. We began by selecting the top

500 rms by market capitalization listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) in both the pre-

adoption and the post-adoption periods.

13

We retain rms that are part of the top 500 by market

capitalization in both periods for our study. This enables the inclusion of rms that are of similar

size before and after the adoption of IFRS, which have previously used Australian GAAP in the

pre-adoption period and later transited mandatorily to IFRS in the post-adoption period for

investigation. Also, sample rms must have scal year-end of 12 months for each sample period

and data available both before and after the adoption of IFRS to enable a comparison between

periods of the same rms, for which all nancial and accounting data were collected from

Connect4, Worldscope, and Thomson One databases. Based on these requirements, our nal

sample consists of 172 Australian listed rms, which provides 1,376 (8 years 3172 rms) rm-year

observations for the study.

14

We use each rm as its own control for two reasons. First, the adoption of IFRS in Australia is

compulsory, beginning on the same date for both listed and unlisted reporting entities governed by

the Corporations Act 2001. Therefore, there is no benchmark rm using Australian GAAP available

13

Our cut-off dates in selecting the top 500 Australian listed rms by market capitalization for both the pre-

adoption and the post-adoption periods are June 30, 2004, and June 30, 2009. June 30, 2009, was the last

nancial year end (in the post-adoption period) for our sample period, while June 30, 2004, was the last nancial

year end in June (in the pre-adoption period) in which all sample rms prepared their nancial statements under

Australian GAAP (including for rms with December 31 year end and those with post-December 31 year end).

14

There are equal numbers of rm-year observations in the pre-adoption period (i.e., 688 rm-year observations)

and the post-adoption period (i.e., 688 rm-year observations).

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 125

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

in the post-adoption period for comparison. Secondly, a matched sample using benchmark rms

from other countries that either preclude or have not mandated the use of IFRS introduces country-

level differences. Additionally, it is not plausible to identify a country that possesses similar unique

features like Australia in terms of its institutional framework but is yet to adopt IFRS. Hence,

constructing a sample using the same rms as well as standardizing the rm-year observations in

both the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods would make it more likely that any change

observed in accounting quality is attributable to the adoption of IFRS. At the same time, these

requirements also control for rm-specic factors.

Table 2 presents the sample industry breakdown that has been categorized based on the Global

Industry Classication Standard (GICS) Sector Codes (two-digit). As shown in the table, the

sample rms are spread across a wide range of industries, with most in nancials, industrials,

consumer discretionary, and materials.

Consistent with the EU, the Australian transition to IFRS was made effective from January 1,

2005, and therefore would have expected the rst IFRS accounts in the scal year-ended December

31, 2005. However, only 13 percent of the sample rms (as shown in Table 3) have a December

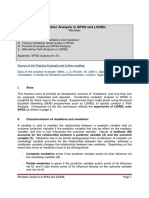

TABLE 1

Sample Selection

No. of Firms Total

Initial sample (All Ordinaries) as of June 30, 2004 (pre-adoption period)

a

496

Initial sample (All Ordinaries) as of June 30, 2009 (post-adoption period)

b

493

Firms included in All Ordinaries as of both June 30, 2004, and June 30, 2009 249

Less: Firms that are eliminated due to missing data from 2001 to 2009

c

52

Less: Firms that are exempted from the Australian mandatory IFRS adoption

d

11

Less: Firms that changed their scal year-end during 2001 to 2009

e

14

Final Sample: Number of Firms 172

Number of Reporting Years

(1) Pre-Adoption Period 4 years

(2) Post-Adoption Period 4 years

Total Reporting Years 8 years

Final Sample: Number of Firm-Year Observations 1,376

a,b

The ASX denes All Ordinaries (All Ords) as capitalization weighted index of performance of share prices of about

500 of the largest Australian companies. The constituent list for All Ordinaries Index includes only the eligible

companies listed on the ASX and thus may not have exactly 500 companies at a particular date (ASX 2011).

c

Most rms are excluded from the sample due to the unavailability of data for closely held shares (CLOSE). Given that

this information is not readily available from the published annual reports, these missing values cannot be obtained

feasibly from other sources (for example, Connect4). The exclusion of these rms from the sample is unlikely to

affect the conclusions of this study on the basis that the remaining rm-year observations are still sufcient to

construct a large sample (. 100).

d

Firms are exempted from the Australian mandatory adoption of IFRS because they are either dual listed on the ASX

(for example, Rio Tinto Limited) or incorporated outside Australia (for example, Singapore Telecom Ltd.).

Therefore, they have not prepared their nancial reports under Australian GAAP (in the pre-adoption period) and the

Australian equivalent of IFRS (in the post-adoption period) to enable a comparison in this study. This elimination is

also similarly done by Kvaal and Nobes (2010).

e

Firms do not prepare nancial statements for a scal year of 12 months in the rst year of changing their scal year-

end. For the purpose of determining annual return for the value relevance metrics, these rms are excluded from the

sample to standardize comparison between periods.

126 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

nancial year end date. As a result, the 2006 reporting year became the rst period in which the

majority sample rms with non-December nancial year end dates were required to comply with

IFRS reporting. Table 4 presents the reporting years for which data are grouped into the pre-

adoption and the post-adoption periods, on the basis of whether the sample rms have scal year-

end of December 31 or post-December 31.

15

This approach ensures that data for the post-adoption

period consist of the rst four reporting periods under IFRS for all sample rms, with an equal

number of observations for the same rms in the pre-adoption period.

Accounting Quality Metrics

Following prior research, we operationalize accounting quality based on three perspectives: (1)

earnings management, (2) timely loss recognition, and (3) value relevance (Lang et al. 2006; Barth et

al. 2008; Christensen et al. 2008; Paananen and Lin 2009). Albeit there are numerous ways proposed

by prior studies in measuring accounting quality,

16

there is still a lack of consensus on the denition

of the concept. Therefore, we attempt to adopt these three perspectives, in order to draw upon the

interpretation of Ball et al. (2003, 237) on accounting quality. That is, nancial reporting quality is

related to the concept of transparency, dened as the ability of users to see through the nancial

statements to comprehend the underlying accounting events and transactions in the rm.

Consistent with this interpretation, we attempt to associate our concept of accounting quality

with accounting-based attributes,

17

by adopting earnings management and timely loss recognition

constructs that allow us to concentrate on the quality of accounting information prepared under

TABLE 2

Industry Breakdown

GICS Classication GICS Sector Code Number of Firms Percentage

Energy 10 8 4.65%

Materials 15 25 14.54%

Industrials 20 30 17.44%

Consumer Discretionary 25 28 16.28%

Consumer Staples 30 10 5.82%

Health Care 35 16 9.30%

Financials 40 40 23.26%

Information Technology 45 9 5.23%

Telecommunication Services 50 3 1.74%

Utilities 55 3 1.74%

Total 172 100.00%

GICS Global Industry Classication Standard.

15

A year end date of June 30 is most common for this group of rms.

16

Other measures include accrual quality, persistence, predictability, and conservatism (Schipper and Vincent

2003; Francis et al. 2004).

17

Francis et al. (2004) identify seven earnings attributes as related to earnings quality (similar to accounting

quality). They classify seven earnings attributes into two categories: accounting based (accrual quality,

persistence, predictability, and smoothness) and market based (value relevance, timeliness, and conservatism).

As explained in their paper, accounting-based attributes use only accounting information, while market-based

attributes depend on the relation between market data and accounting data.

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 127

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

Australian GAAP (in the pre-adoption period) and IFRS (in the post-adoption period). At the same

time, we also include market-based constructs for value relevance to complement those accounting-

based constructs in strengthening our ndings for the multi-faceted concept of accounting quality.

Earnings Management

We develop four constructs to proxy two perspectives of earnings management: (1) earnings

smoothing and (2) managing earnings toward a positive target. This is done by closely following

the metrics used in Barth et al. (2008), and they include the variability of the change in net income

(DNI), the mean ratio of the variability of the change in net income (DNI) to the variability of the

change in operating cash ows (DOCF), the Spearman correlation of accruals (ACC) and cash

ows (CF), as well as the coefcient from a logit regression of small positive earnings (SPOS).

By using a variety of constructs to measure earnings management, we aim to provide evidence

that is less circumstantial, given that earnings management is neither directly observable nor can be

easily disentangled from the effects of accounting differences arising from the changes in the

underlying economics (Lang et al. 2003). Nevertheless, we also attempt to minimize the inuence of

other factors on earnings management, by including several control variables that are identied by

prior studies to be unrelated to the mandatory adoption of IFRS (Lang et al. 2006; Barth et al. 2008).

The rst earnings smoothing measure is based on the variability of the change in annual net

income (scaled by total assets) (DNI). This measure is designed to detect the presence of earnings

smoothing because to the extent that earnings are being opportunistically managed, all else equal,

there should be lower earnings variability. Therefore, we measure the uctuation in earnings stream

by the change in annual net income. The reported earnings are also rst being deated (by total assets)

so that the earnings series is more likely to demonstrate a random walk and can be inferred as less

affected by the fundamental differences among rms (Lev 1983). Nonetheless, the reported earnings

can still be sensitive to a wide range of other factors that are unattributable to the mandatory adoption

of IFRS. As a result, we include a number of control variables identied in prior literature (Lang et al.

2006; Barth et al. 2008) to partially mitigate these confounding effects before inferring the results as

the effect of changing to IFRS compulsorily. This means that the interpretation of the regression thus

focuses on the residuals that are generated from the relevant regression, rather than on the reported

earnings themselves. On this basis, the rst earnings smoothing measure is taken as the variance of

the residuals (Equation (1)) from a regression of the change in annual net income (scaled by total

assets) (DNI) on the control variables (Equation (1a)):

18

TABLE 3

Fiscal Year End Breakdown

Fiscal Year End

Number of

Firms

Number of

Firm-Year

Observations Percentage

First IFRS

Reporting Year

Reporting Year

Observations

December 31 23 92 13.37% Year 2005 20012008

Post-December 31 149 596 86.63% Year 2006 20022009

Total 172 688 100.00%

18

As explained by Barth et al. (2008), using this approach assumes that the measure of the variability of the change

in net income (DNI) is unrelated to the control variables.

128 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

Variability of DNI

#

r

2

ErrorDNIi

; 1

where:

DNI

#

residuals from the regression of DNI on the control variables (Equation (1a)).

Equation (1a): Regression of DNI on the control variables:

DNI

i

a

0

a

1

SIZE

i

a

2

GROWTH

i

a

3

EISSUE

i

a

4

LEV

i

a

5

DISSUE

i

a

6

TURN

i

a

7

CF

i

a

8

AUD

i

a

9

NUMEX

i

a

10

XLIST

i

a

11

CLOSE

i

a

12

IND

i

a

13

TIME

i

Error

DNIi

;

1a

where:

SIZE natural logarithm market value of equity;

GROWTH percentage change in sales;

EISSUE percentage change in common stock;

LEV total liabilities divided by equity book value;

DISSUE percentage change in total liabilities;

TURN sales divided by total assets;

CF annual net cash ow from operating activities divided by total assets;

AUD dummy variable that equals 1 if the rms auditor is PwC, KPMG, Arthur Andersen,

Ernst & Young, or Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, and 0 otherwise;

NUMEX number of exchanges on which a rms stock is listed;

XLIST dummy variable that equals 1 if the rm is listed on any U.S. stock exchange, and

Worldscope indicates that the U.S. exchange is not the rms primary exchange;

CLOSE percentage of closely held shares of the rm as reported by Worldscope;

IND dummy variables for industry xed effects, classied using the two-digit Global

Industry Classication Standard (GICS) Codes; and

TIME dummy variables for time (year) xed effects.

The above regression is run separately for the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods by using

the rm-year observations that have been pooled into the respective time periods (either the pre-

adoption or the post-adoption periods). This results in two sets of residuals being generated, and the

variance of the residuals is calculated for each respective group before being compared using a

variance ratio F-test.

To the extent that a variety of control variables have been included in the rst measure to

account for the inuence of other factors, the volatility of earnings may still be inuenced by

various rm-specic characteristics that would remain prevalent in the underlying volatility of the

TABLE 4

Reporting Years: The Pre-Adoption Period and the Post-Adoption Period

Firms with Fiscal

Year End of:

Pre-Adoption Period Post-Adoption Period

1st Year 2nd Year 3rd Year 4th Year 1st Year 2nd Year 3rd Year 4th Year

December 31 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

Post-December 31

(e.g., June 30)

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 129

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

cash ow stream. When rms experience more volatile cash ows, then rms should also expect a

naturally more volatile net income. Therefore, the second earnings smoothing measure extends the

analysis of the rst measure by benchmarking it against the volatility of cash ows. This involves

calculating the ratio of the variance of the changes in annual net income (DNI) to the variance of the

change in operating cash ows (DOCF).

Similar to the rst measure, the volatility of cash ows is taken as the variance of the residuals

(DOCF

#

) (Equation (2)) from a regression of the change in operating cash ows (scaled by total

assets) (DOCF) (Equation (2a)):

Variability of DNI

#

Variability of DOCF

#

r

2

ErrorDNIi

r

2

ErrorDOCFi

; 2

where:

DNI

#

residuals from the regression of DNI on the control variables (Equation (1a)); and

DOCF

#

residuals from the regression of DOCF on the control variables (Equation (2a)).

Equation (2a): Regression of DOCF on the control variables:

DOCF

i

a

0

a

1

SIZE

i

a

2

GROWTH

i

a

3

EISSUE

i

a

4

LEV

i

a

5

DISSUE

i

a

6

TURN

i

a

7

CF

i

a

8

AUD

i

a

9

NUMEX

i

a

10

XLIST

i

a

11

CLOSE

i

a

12

IND

i

a

13

TIME

i

Error

DOCFi

:

2a

Again, the above regression is run separately for the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods by

using the rm-year observations that have been pooled into the respective time periods. This results

in two sets of residuals being generated for the change in operating cash ows (DOCF

#

), and the

variance of the residuals is calculated for each respective group before computing the ratio for the

pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods.

Unlike the rst earnings smoothing measure, there is no known formal statistical test to

compare the difference between the respective ratios of variances (DNI

#

/DOCF

#

) for the pre-

adoption and the post-adoption periods. As an alternative, we follow the methodology of Lang et al.

(2003) to test whether the ratio of variances is signicantly less than 1 for each group respectively

using a variance ratio F-test.

Our third earnings smoothing measure is the Spearman correlation between accruals and cash

ows. It is expected that rms use accruals when they engage in earnings management, especially in

time of poor cash ows, to smooth cash ows variability. While there is naturally a negative correlation

between accruals (ACC) and cash ows (CF), prior studies argue that a larger magnitude of negative

correlation between these variables is indicative of earnings smoothing, all else equal (Myers et al.

2007; Land and Lang 2002; Lang et al. 2003; Lang et al. 2006). Consistent with the previous two

measures, other factors could similarly inuence cash ows (CF) and accruals (ACC). As a result, the

Spearman partial correlation between these two variables (Equation (3)) is determined based on the

residuals from regressions of cash ows and accruals (Equation (3a) and Equation (3b)) as follows:

19

Spearman correlation between cash flows CF

#

and accruals ACC

#

CORR Error

CFi

; Error

ACCi

; 3

where:

19

Since one of the dependent variables used for this analysis is CF, the same variable is now excluded as a control

variable.

130 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

CF

#

residuals from the regression of CF on the control variables (Equation (3a)); and

ACC

#

residuals from the regression of ACC on the control variables (Equation (3b)).

Equation (3a): Regression of CF on the control variables:

CF

i

a

0

a

1

SIZE

i

a

2

GROWTH

i

a

3

EISSUE

i

a

4

LEV

i

a

5

DISSUE

i

a

6

TURN

i

a

7

AUD

i

a

8

NUMEX

i

a

9

XLIST

i

a

10

CLOSE

i

a

11

IND

i

a

12

TIME

i

Error

CFi

: 3a

Equation (3b): Regression of ACC on the control variables:

ACC

i

a

0

a

1

SIZE

i

a

2

GROWTH

i

a

3

EISSUE

i

a

4

LEV

i

a

5

DISSUE

i

a

6

TURN

i

a

7

AUD

i

a

8

NUMEX

i

a

9

XLIST

i

a

10

CLOSE

i

a

11

IND

i

a

12

TIME

i

Error

ACCi

;

3b

where ACC

i

NI

i

CF

i

.

After obtaining the Spearman correlations rho for the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods

respectively, the two Spearman correlations rho are then compared using a signicance test suggested

by Sheskin (2004) to evaluate a change in the earnings smoothing behavior after IFRS adoption.

To examine earnings management from the perspective of managing earnings toward a positive

target, we pool all observations for the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods to measure the

frequency of small positive earnings (SPOS). Following prior research, we use a dummy variable

for small positive earnings (SPOS) that sets to 1 for observations for which annual net income

(scaled by total assets) is between 0 and 0.01, and sets to 0 otherwise (Lang et al. 2003; Lang et al.

2006; Barth et al. 2008). We also modify the model by Barth et al. (2008), by swapping the binary

variable of POST with the binary variable of SPOS as the dependent variable for the logit

regression. We consider this modication to be more appropriate for this study because the

Australian adoption of IFRS was compulsory, and thus the variable POST is no longer

representative of an event that could be dependent on rms reporting small positive earnings (i.e.,

SPOS). Instead, this enables us to examine whether the probability of rms reporting small positive

earnings (SPOS) has changed after rms transited to IFRS (POST), together with the control

variables used in previous measures, by interpreting the coefcient b

1

from a logit model.

Equation (4): Logit regression of SPOS on POST and the control variables:

SPOS

i

b

0

b

1

POST

i

b

2

SIZE

i

b

3

GROWTH

i

b

4

EISSUE

i

b

5

LEV

i

b

6

DISSUE

i

b

7

TURN

i

b

8

CF

i

b

9

AUD

i

b

10

NUMEX

i

b

11

XLIST

i

b

12

CLOSE

i

b

13

IND

i

b

14

TIME

i

Error

i

;

4

where:

POST dummy variable that equals 1 if observations are in the post-adoption period, and 0

otherwise; and

SPOS dummy variable that equals 1 if net income scaled by total assets is between 0 and

0.01, and 0 otherwise.

Timely Loss Recognition

Considering that prior studies often cite the reluctance of rms to recognize large losses in a

timely manner (Ball et al. 2003; Leuz et al. 2003; Lang et al. 2003; Lang et al. 2006; Barth et al.

2008), we follow the earnings threshold used in prior studies to measure the frequency of large

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 131

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

losses being reported, by using a dummy variable that sets to 1 for observations for which annual

net income (scaled by total assets) is less than 0.20, and sets to 0 otherwise (Leuz et al. 2003;

Lang et al. 2003; Lang et al. 2006; Barth et al. 2008). Having pooled all observations, we again

modify the timely loss recognition model used by Barth et al. (2008). We use the result for the

frequency of large losses (LNEG) as the dependent variable and estimate a logit regression on a

dummy variable for the post-adoption period (POST), together with the control variables. The

probability that the adopting rms report large losses differently between the pre-adoption and the

post-adoption periods is interpreted based on the coefcient k

1

.

Equation (5): Logit Regression of LNEG on POST and the Control Variables:

LNEG

i

k

0

k

1

POST

i

k

2

SIZE

i

k

3

GROWTH

i

k

4

EISSUE

i

k

5

LEV

i

k

6

DISSUE

i

k

7

TURN

i

k

8

CF

i

k

9

AUD

i

k

10

NUMEX

i

k

11

XLIST

i

k

12

CLOSE

i

k

13

IND

i

k

14

TIME

i

Error

i

;

5

where:

LNEG dummy variable that equals 1 if net income scaled by total assets is less than 0.20,

and 0 otherwise.

Value Relevance

As mentioned earlier, the preceding analyses focus mainly on the quality of accounting

information without much reference to market data. Considering that the introduction of IFRS has a

capital-market orientation, we employ three value relevance measures that are consistent with Barth

et al. (2008) to examine the association between accounting data and share price. All else equal,

rms with higher accounting quality are expected to have a higher association between share price

and accounting data.

Our rst value relevance measure is based upon the explanatory power of the price regression.

To obtain the adjusted R

2

that is controlled for industry and for time effects, we adopt the two-stage

regression technique used in Barth et al. (2008). We rst obtain residuals from a regression of share

price (P) on industry and time (year) xed effects, before regressing the residuals (P*) on net

income per share (NI/P) and book value of equity per share (BVEPS). To ensure that accounting

information has had sufcient time to be absorbed by the market, we measure share price three

months after the scal year-end.

20

Equation (6): Regression of P* on BVEPS and NIPS:

P

i

d

0

d

1

BVEPS

i

d

2

NIPS

i

Error

i

; 6

where:

P share price three months after the scal year-end date;

P* residuals from a regression of P on industry and time (year) xed effects;

BVEPS book value of equity per share; and

NIPS net income per share.

Consistent with other measures, the above regression is run separately for the pre-adoption and the

20

This is in line with Section 319 of the Corporations Act 2001, which requires Australian listed corporations to

lodge their nancial reports within three months after the end of the scal year-end to the Australian Securities

and Investments Commission (ASIC).

132 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

post-adoption periods by using the rm-year observations that have been pooled into the respective

time periods.

The second and third value relevance measures are based upon the explanatory power from a

Basu (1997) reverse return regression of net income per share (NI/P) on annual share price

returns. Consistent with prior research, we run separate regressions for rms with good news

(rms with non-negative annual share returns) and rms with bad news (rms with negative

annual share returns) (Basu 1997; Ball et al. 2000; Barth et al. 2008), while also similarly

controlling for industry and time (year) xed effects as in the previous measure.

Equation (7): Regression of [NI/P]* on RETURN:

NI=P

i

d

0

d

1

RETURN

i

Error

i

; 7

where:

NI/P net income per share divided by the beginning of scal year share price;

[NI/P]* residuals from a regression of NI/P on industry and time (year) xed effects; and

RETURN shareholders total annual return from nine months before the scal year-end to

three months after the scal year-end.

The above regression is run separately for the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods for both

good news and bad news rms using the rm-year observations that have been pooled into the

respective time periods.

IV. RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics for both test variables and control variables across the

pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods. A comparison between the periods reveals that the

mean or median values across all continuous test variables are signicantly different, with the

exception of accruals (ACC). This could possibly be explained by the economic downturn

experienced worldwide during the post-adoption period, therefore causing signicant changes to the

test variables. It is interesting to note that the change in net income (DNI) was increasing (mean and

median are greater than 0) during the pre-adoption period, but the opposite trend is observed during

the post-adoption period (negative DNI). In addition, the shareholders return (RETURN) has

decreased tremendously from 32.05 percent (mean) during the pre-adoption period to 7.87 percent

(mean) after the adoption of IFRS. Without controlling for other factors, Table 5 indicates that the

sample rms experienced signicant changes in variability (standard deviation) in the post-adoption

period than in the pre-adoption period. This could also partially reect the uncertainty in the

economic environment faced by the sample rms during the economic crisis, which emphasizes the

need to incorporate control variables in the regression analyses.

In terms of control variables, Table 5 shows that the sample rms have grown signicantly

larger (SIZE) after moving toward IFRS (both mean and median), despite showing insignicant

difference in the change in common stock (EISSUE) (both mean and median). Given that rms are

getting bigger (SIZE) but the level of common stock (EISSUE) remains relatively stable, it is not

surprising to nd that the leverage ratio (LEV) and the percentage change in total liabilities

(DISSUE) have increased following IFRS adoption. Moreover, the adoption of IFRS increases the

likelihood that the sample rms are audited by one of the Big 4 auditors

21

(AUD), possibly to

21

Previously, the ve largest auditing rms were known as the Big 5 auditors. With the collapse of Arthur

Andersen, the remaining four rms are collectively labeled as the Big 4 auditors. Both expressions equally

represent a group of the largest auditing rms in the accounting industry.

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 133

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

TABLE 5

Descriptive Statistics

Pre (n 688) Post (n 688)

Mean Median Std. Dev. Mean Median Std. Dev.

Test Variables

DNI 0.0060 0.0028 0.0794 0.0085*** 0.0026*** 0.0919***

DOCF 0.0074 0.0035 0.0948 0.0007 0.0016* 0.0828***

ACC 0.0332 0.0291 0.0787 0.0347 0.0234 0.0764

CF 0.0866 0.0858 0.1296 0.0994** 0.0818 0.1113***

SPOS 0.0465 0.0000 0.2107 0.0698* 0.0000 0.2549

LNEG 0.0451 0.0000 0.2076 0.0378 0.0000 0.1908

P 5.5676 3.3950 5.8873 8.0574*** 4.1400*** 9.7041***

NI/P 0.0536 0.0590 0.1033 0.0383** 0.0594 0.1393***

BVEPS 2.2565 1.5340 2.1987 3.1783*** 1.8944*** 3.3482***

NIPS 0.3016 0.1806 0.4369 0.4825*** 0.2615*** 0.7284***

RETURN 0.3205 0.2206 0.4770 0.0787*** 0.0490*** 0.3908***

Control Variables

SIZE 6.3523 6.0717 1.7512 6.9340*** 6.7380*** 1.6881

GROWTH 0.1931 0.1015 0.3929 0.1480** 0.0974 0.3337***

EISSUE 0.1920 0.0394 0.3650 0.2022 0.0356 0.4919***

LEV 1.6581 0.8716 2.7939 1.9260* 0.9859*** 3.1401***

DISSUE 0.2186 0.0634 0.5980 0.2556 0.1109** 0.6488**

TURN 0.8893 0.6769 0.7689 0.8361 0.7064 0.7013**

AUD 0.8372 1.0000 0.3694 0.8677 1.0000 0.3390

NUMEX 1.1831 1.0000 0.5696 1.1570 1.0000 0.5410

XLIST 0.0349 0.0000 0.1836 0.0349 0.0000 0.1836

CLOSE 0.3651 0.3744 0.2326 0.3453 0.3613 0.2299

*, **, *** Represent signicant difference between the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods at the 10 percent, 5

percent, and 1 percent condence levels, respectively (two-tailed).

All continuous variables are winsorized at the 5 percent level.

Variable Denitions:

DNI change in annual net income, where net income is scaled by end-of-year total assets;

DOCFchange in annual net cash ows from operating activities, where cash ows is scaled by end-of-year total assets;

ACC net income less cash ow from operating activities, scaled by end-of-year total assets;

CF annual net cash ow from operating activities divided by total assets;

SPOS dummy variable that equals 1 for observations for which annual net income scaled by total assets is between 0

and 0.01, and 0 otherwise;

LNEG dummy variable that equals 1 for observations for which annual net income scaled by total assets is less than

0.20, and 0 otherwise;

P stock price three months after the scal year-end;

NIPS net income per share;

BVEPS book value of equity per share;

NI/P net income per share divided by beginning of year price;

RETURNshareholders total annual return from nine months before the scal year-end to three months after the scal

year-end;

SIZE natural logarithm market value of equity;

GROWTH percentage change in sales;

EISSUE percentage change in common stock;

LEV total liabilities divided by equity book value;

DISSUE percentage change in total liabilities;

(continued on next page)

134 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

overcome the reporting complexity faced during the transition to new standards. Surprisingly, the

sample rms are, on average, listed on fewer stock exchanges (NUMEX) in the post-adoption

period (1.1570) than in the pre-adoption period (1.1837). Additionally, there is no change in terms

of rms listing on the U.S. stock exchanges

22

(XLIST) before and after the adoption. These two

preliminary ndings are contrary to the common argument that the use of IFRS facilitates access to

international capital markets (Jones and Higgins 2006).

Table 6 provides a Spearman correlation matrix for the continuous variables, with correlations

for the pre-adoption period being shown in Panels A and B and the post-adoption period being

shown in Panels C and D. Overall, correlations between the variables in both periods are modest,

which suggests that multicollinearity is not a substantive issue. The only exception is correlation

between share price (P) and net income per share (NIPS), in which correlation between these two

variables is the highest in both the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods, and is greater than

0.70. Furthermore, accruals (ACC) and cash ows (CF) are also found to be negatively correlated in

both the pre-adoption (0.55 signicant at 1 percent) and the post-adoption periods (0.47

signicant at 1 percent), which is consistent with the prior expectation that the negative correlation

reects the natural outcome of accrual accounting (Leuz et al. 2003; Barth et al. 2008). In addition,

three variablesincluding the change in net income (DNI), the change in cash ows (DOCF), as

well as cash ows (CF)are all positively correlated at the 1 percent signicance level in both the

pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods. These positive relationships are also expected, given

that a rms reported earnings (e.g., DNI) should be reective of its own cash ow stream (e.g.,

DOCF and CF).

Empirical Results

Earnings Management

In terms of earnings management, the results reported in Panel A of Table 7 are mostly

consistent with our expectations that the adoption of IFRS in Australia had signicantly impacted

accounting quality.

As emphasized earlier, the analyses for the rst three earnings management measures focus on the

residuals from regressing each dependent variable on a specic set of control variables. Based on this

approach, a comparison of the residual variance (for DNI

#

) shows that the variability of the change in

net income is signicantly higher in the post-adoption period (0.0072) than in the pre-adoption period

(0.0056), suggesting that income-smoothing behavior has reduced following IFRS adoption.

To further support the rst nding, the second earnings management measure analyzes the

variability of the change in operating cash ows for both the pre-adoption and the post-adoption

TABLE 5 (continued)

TURN sales divided by total assets;

AUDdummy variable that equals 1 if the rms auditor is PwC, KPMG, Arthur Andersen, Ernst & Young, or Deloitte

Touche Tohmatsu, and 0 otherwise;

NUMEX number of exchanges on which a rms stock is listed;

XLISTdummy variable that equals 1 if the rm is listed on any U.S. stock exchange and Worldscope indicates that the

U.S. exchange is not the rms primary exchange, and 0 otherwise; and

CLOSE percentage of closely held shares of the rm as reported by Worldscope.

22

This can be interpreted from the variable XLIST because all sample rms with a listing on any U.S. stock

exchanges have their primary listing outside of the U.S.

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 135

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

TABLE 6

Spearman Correlation Matrix between Variables for the Pre-Adoption Period and the

Post-Adoption Period

Panel A: Pre-Adoption Period

DNI DOCF ACC CF P NI/P BVEPS NIPS

DNI 1.00

DOCF 0.42*** 1.00

ACC 0.10** 0.28*** 1.00

CF 0.22*** 0.35*** 0.55*** 1.00

P 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.21*** 1.00

NI/P 0.32*** 0.08** 0.23*** 0.19*** 0.06 1.00

BVEPS 0.05 0.04 0.01 0.06 0.59*** 0.25*** 1.00

NIPS 0.22*** 0.03 0.14*** 0.25*** 0.70*** 0.51*** 0.66*** 1.00

RETURN 0.31*** 0.17*** 0.10** 0.20*** 0.05 0.10** 0.13*** 0.03

SIZE 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.05 0.65*** 0.05 0.60*** 0.55***

GROWTH 0.18*** 0.10*** 0.07* 0.13*** 0.10** 0.18*** 0.03 0.17***

EISSUE 0.10*** 0.12*** 0.10** 0.21*** 0.01 0.12*** 0.05 0.05

LEV 0.07* 0.01 0.08** 0.04 0.35*** 0.13*** 0.31*** 0.32***

DISSUE 0.19*** 0.14*** 0.14*** 0.12*** 0.03 0.01 0.03 0.03

TURN 0.13*** 0.13*** 0.26*** 0.57*** 0.12*** 0.14*** 0.09** 0.13***

NUMEX 0.03 0.00 0.07* 0.06 0.14*** 0.07* 0.07* 0.05

CLOSE 0.00 0.03 0.04 0.00 0.16*** 0.02 0.19*** 0.15***

Panel B: Pre-Adoption Period (continued)

RETURN SIZE GROWTH EISSUE LEV DISSUE TURN NUMEX CLOSE

RETURN 1.00

SIZE 0.14*** 1.00

GROWTH 0.18*** 0.00 1.00

EISSUE 0.05 0.03 0.19*** 1.00

LEV 0.00 0.37*** 0.00 0.01 1.00

DISSUE 0.06 0.02 0.36*** 0.31*** 0.06 1.00

TURN 0.11*** 0.12*** 0.11*** 0.13*** 0.22*** 0.12*** 1.00

NUMEX 0.10** 0.29*** 0.15*** 0.03 0.07* 0.18*** 0.14*** 1.00

CLOSE 0.03 0.21*** 0.02 0.09** 0.07* 0.00 0.02 0.05 1.00

*, **, *** Represent the 10 percent, 5 percent and 1 percent level of signicance in two-tailed tests, respectively.

Panel C: Post-Adoption Period

DNI DOCF ACC CF P NI/P BVEPS NIPS

DNI 1.00

DOCF 0.35*** 1.00

ACC 0.18*** 0.28*** 1.00

CF 0.20*** 0.27*** 0.47*** 1.00

P 0.13*** 0.01 0.09** 0.20*** 1.00

NI/P 0.28*** 0.04 0.30*** 0.24*** 0.07* 1.00

BVEPS 0.04 0.02 0.16*** 0.14*** 0.65*** 0.18*** 1.00

NIPS 0.26*** 0.012 0.28*** 0.24*** 0.78*** 0.53*** 0.66*** 1.00

(continued on next page)

136 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

periods to ascertain whether the observed increase in the volatility of income is also similarly found in

the volatility of cash ows. It is found that the ratio of the variance of the change in net income (DNI

#

)

to the variance of the change in operating cash ows (DOCF

#

) is substantially higher in the post-

adoption period (1.3250) than in the pre-adoption period (0.8070). Even without a statistical test to

determine whether the difference between the ratios is signicant, a change in the ratio from less than

1 to greater than 1 further indicates that it is not a higher volatility of cash ows that drives the higher

earnings variability in the post-adoption period relative to the pre-adoption period. By analyzing the

ratio of variances for the respective periods, only the pre-adoption period has a ratio signicantly less

than 1 (at the 0.01 level). This again provides an indication that the variability of the change in net

income in the pre-adoption period is below the variability of the change in operating cash ows. All

these results together suggest that the smoother earnings stream observed when Australian GAAP

were being used is not a result of smoother cash ow stream but more likely by the effect of accruals,

and that the adoption of IFRS has subsequently reversed that practice.

The result for our third measure of correlation between accruals (ACC) and cash ows (CF)

shows that the correlation between these two variables has become less negative in the post-

adoption period (0.4499) than in the pre-adoption period (0.4553). This corresponds with the results

on the rst two measures, although the difference is not signicant, to suggest that earnings

smoothing has reduced following the adoption of IFRS.

While all the ndings so far consistently support the notion that the adoption of IFRS has

lowered earnings management by way of smoothing, the signicant coefcient for POST in the

TABLE 6 (continued)

DNI DOCF ACC CF P NI/P BVEPS NIPS

RETURN 0.29*** 0.16*** 0.04 0.20*** 0.28*** 0.06 0.03 0.18***

SIZE 0.09** 0.01 0.07* 0.00 0.65*** 0.01 0.54*** 0.52***

GROWTH 0.16*** 0.18*** 0.02 0.16*** 0.20*** 0.09** 0.09** 0.18***

EISSUE 0.05 0.05 0.02 0.16*** 0.06 0.10*** 0.08** 0.00

LEV 0.01 0.01 0.07* 0.16*** 0.27*** 0.01 0.20*** 0.20***

DISSUE 0.06 0.14*** 0.15*** 0.04 0.09** 0.07* 0.00 0.15***

TURN 0.09** 0.07* 0.24*** 0.51*** 0.11*** 0.11*** 0.10*** 0.08**

NUMEX 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.09** 0.05 0.08** 0.01 0.01

CLOSE 0.03 0.00 0.07* 0.05 0.13*** 0.02 0.19*** 0.13***

Panel D: Post-Adoption Period (continued)

RETURN SIZE GROWTH EISSUE LEV DISSUE TURN NUMEX CLOSE

RETURN 1.00

SIZE 0.13*** 1.00

GROWTH 0.13*** 0.07* 1.00

EISSUE 0.02 0.11*** 0.22*** 1.00

LEV 0.04 0.32*** 0.09** 0.08** 1.00

DISSUE 0.12*** 0.03 0.39*** 0.19*** 0.16*** 1.00

TURN 0.07* 0.18*** 0.14*** 0.06 0.12*** 0.08** 1.00

NUMEX 0.03 0.19*** 0.08** 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.19*** 1.00

CLOSE 0.01 0.20*** 0.06 0.10*** 0.09** 0.06* 0.09** 0.01 1.00

*, **, *** Represent the 10 percent, 5 percent and 1 percent level of signicance in two-tailed tests, respectively.

The Impact of Mandatory IFRS Adoption on Accounting Quality 137

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

TABLE 7

Accounting Quality Analysis

a

Panel A: Earnings Management Metrics

Prediction

Pre

(n 688)

Post

(n 688)

Eq. (1): Variability of DNI

#b

Post 6 Pre 0.0056 0.0072***

Eq. (2): Variability of DNI

#

over DOCF

#c,d

,1 0.8070

1.3250

Eq. (3): Correlation of ACC

#

and CF

#e

Post 6 Pre (0.4553) (0.4499)

Eq. (4): Small positive net income (SPOS)

f

6 0 1.8400***

Panel B: Timely Loss Recognition Metric

Prediction Pre (n 688)

Post

(n 688)

Eq. (5): Large negative net income (LNEG)

g

6 0 2.0834***

Panel C: Value Relevance Metrics

Prediction Pre (n 688)

Post

(n 688)

Eq. (6): Price model

h

Post 6 Pre 0.4827 0.5396***

Eq. (7): Return model

i

Good news Post 6 Pre (0.0001) (0.0005)

Bad news Post 6 Pre 0.0700 0.0869***

*** Represents signicant difference between the pre-adoption and the post-adoption periods at the 1 percent condence

level (two-tailed).

Signicantly less than 1 at the 1 percent level (left-tailed).

a

We have not presented the full regression results in this paper, but would be happy to provide them upon request.

b

Variability of DNI

#

is the variance of residuals from a regression of the change in annual net income (scaled by total

assets), DNI, on the control variables.

c

Variability of DOCF

#

is the variance of residuals from a regression of the change in operating cash ows (scaled by

total assets), DOCF, on the control variables.

d

Variability of DNI

#

over DOCF

#

is the ratio of DNI

#

divided by DOCF

#

.

e

Correlation of ACC

#

and CF

#

is the partial Spearman correlation between the residuals from accruals, ACC, and cash

ows, CF, regressions.

f

SPOS is a dummy variable that sets to 1 for observations for which the annual net income scaled by total assets is

between 0 and 0.01, and sets to 0 otherwise. SPOS is regressed on a dummy variable (POST) that equals 1 for

observations in the post-adoption period, and 0 otherwise. The coefcient on POST is tabulated.

g

LNEG is a dummy variable that sets to 1 for observations for which the annual net income scaled by total assets is less

than 0.20, and sets to 0 otherwise. LNEG is regressed on a dummy variable (POST) that equals 1 for observations in

the post-adoption period, and 0 otherwise. The coefcient on POST is tabulated.

h

Adjusted R

2

is obtained from a two-stage regression of stock price (P), where P is stock price as of three months after

the scal year-end. In the rst stage, P is regressed on industry and time (year) xed effects to obtain the residual (P*).

In the second stage, P* is regressed on book value of equity per share (BVEPS) and net income per share (NIPS).

Adjusted R

2

is tabulated.

i

Adjusted R

2

is obtained from a two-stage regression for good/bad news. Good (bad) news observations represent those

for which RETURN is non-negative (negative), where RETURN is shareholders total annual return from nine months

before the scal year-end to three months after the scal year-end. NI/P is rst regressed on industry and time (year)

xed effects, where NI/P is net income per share divided by beginning of year price. In the second stage, the residual

([NI/P]*) from the rst-stage regression is regressed on RETURN. Adjusted R

2

is tabulated separately for good and bad

news subsamples.

138 Chua, Cheong, and Gould

Journal of International Accounting Research

Volume 11, No. 1, 2012

logit regression of small positive income (SPOS),

23

1.84, indicates that there is a signicant

difference in terms of rms managing earnings toward a positive target across the pre-adoption and

the post-adoption periods. This nding is found to be inconsistent with Barth et al. (2008), as they

nd that the IFRS adopting rms exhibit no signicant difference in terms of managing earnings

toward a positive target from those rms that do not adopt IFRS, as well as across time when these