Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Transitions of The Angry Middle Class

Cargado por

Sarath P BabuTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Transitions of The Angry Middle Class

Cargado por

Sarath P BabuCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Transitions of the angry middle class

Online Complaint Forum. - File Your Complaint Here. Immediate Strong Action on

Company. consumer-complaint-forum.akosha.com

Ads by Google

JACK GOLDSTONE

SHARE COMMENT (22) PRINT T+

TOPICS

economy, business and finance

economy (general)

politics (general)

democracy

What the people of India want, just as the angry middle classes in

Ukraine, Bosnia Thailand and Venezuela do, is a government that is

accountable, responsible, and effective in moving their country

further into the modern world

A few years ago, the emerging markets and middle-income developing countries

were considered to have a rosy future the rising middle class was going to

usher in an era of stability, democracy and mass consumer markets that would

lead the world economy.

The global middle class is growing, but the hoped-for smooth democratic

transitions have not occurred. Instead, what we have seen are clashes between an

increasingly angry middle class and governments that have broken faith or taken

them for granted.

Trajectory of confrontations

Last year, two of the most promising emerging market nations Brazil and

Turkey were rocked by massive urban protests. These put in doubt the future

of political parties and leaders that had seemed unassailable. The decision by

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseffs Workers Party to spend lavishly on the

World Cup and Olympics while raising bus fares and letting the exchange value of

the Brazilian Real soar hit hard at the pockets of urban Brazilians. Ms. Rousseff

had to back down and recast her policies. In Istanbul, the decision by Prime

Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to reshape the city with new construction,

including the closing of Gezi Park, a deeply valued urban refuge, gave rise to

protests; Mr. Erdogans decision to respond with excessive force called into

question his commitment to democracy, as did his dismissive disparaging of the

protesters. Eventually, Mr. Erdogan not only backed down, but found himself on

the defensive, with his ministers and party under investigation for corruption.

In Brazil and Turkey both recently emerged from military rule but with an

increasingly established pattern of democracy the regimes avoided the use of

deadly force and backed away from confrontation, seeking instead to respond to

the protesters demands. Yet, in the last few months, other countries that have

only started to move toward democracy more recently or more weakly have seen

similar confrontations, and these have erupted into deadly confrontations, in at

least one case (Ukraine) toppling the regime.

What is responsible for the violent protests that have emerged nearly

simultaneously in the Ukraine, Bosnia, Thailand and Venezuela? As in Brazil and

Turkey, what we are seeing is the real result of the emergence of a global middle

class not merely passive consumers or docile voters, they are demanding that

governments not accustomed to accountability and showing deference to popular

demands start acting like true democracies. Where the rulers of emerging

democracies remain visibly corrupt, or treat crucial foreign and domestic policies

simply as their personal choices to make, they are provoking waves of anger and

mass protests. And where instead of backing down they persist in confrontation,

they are reaping violence and losing control of their country.

What economic indicators show

From So Paulo to Caracas, from Sarajevo to Kiev, and from Istanbul to Bangkok,

we are seeing a similar phenomenon. These are movements of the angry

emerging middle class in countries at a crossroads. If we examine the background

to recent events in the Ukraine, Bosnia, Thailand and Venezuela, we find that

despite the geographic distances that separate them, these countries are

remarkably similar.

All four are middle-income countries. According to the International Monetary

Fund (IMF), the best off, oil-enriched Venezuela, ranks 73rd in per capita GDP

(adjusted for the purchasing power parity of its currency). Thailand ranks 92nd,

Bosnia-Herzegovina ranks 99th, and Ukraine is the poorest, ranking 106th. Thus,

among the worlds 187 countries ranked by the IMF, they are almost exactly in

the middle.

They have just arrived at the point where the vast majority of the population is

literate and expects the government to provide a sound economy, jobs and decent

public services. Yet, they are not yet economically comfortable and secure. That

security, and a better future for themselves and their children, depends very

heavily on whether government leaders will work to provide greater

opportunities and progress for the nation as a whole, or only to enrich and

protect themselves and their cronies. In sum, all these countries are at a point

where limiting corruption and increasing accountability are crucial to whether

their country will continue to catch up to the living standards of richer countries,

or fall back to the standards of poorer ones.

The short-term economic performance of these countries is not as important as

where they stand in this transition, having escaped dire poverty but now just

knocking on the door of modern western-style security and prosperity. In fact,

the short-term performance of these countries is varied. According to the World

Bank, in 2012, the economy of Ukraine grew by only 0.2 per cent, while that of

Bosnia-Herzegovina declined by 0.7 per cent. In contrast, Thailands economy

performed wonderfully, with GDP increasing by 6.5 per cent, and Venezuela also

enjoyed strong growth of 5.6 per cent.

Yet, short-term economic performance can be misleading. In 2010, just before

Egypt erupted into turmoil, the nations economy had enjoyed 5.3 per cent GDP

growth; in the first half of 2010, Syrias economy boomed with a 6.0 per cent

GDP gain. The problem is that these short-term, overall growth rates tell us

nothing about how prosperity has been distributed, about the gap between

economic growth and political exclusion, or the amount of economic growth that

is stolen through corruption. It is these latter factors that feed anger that can

erupt in protests.

Import for India

Given that people are protesting not out of sheer poverty, but against rulers they

see as stealing their chances to move forward, it should be no surprise that these

four countries are also rated as highly corrupt. According to the corruption index

compiled by Transparency International (TI), Thailand, Ukraine and Venezuela

are among the most corrupt countries in the world: Thailand ranks 102nd,

Ukraine 144th, and Venezuela at 160th in the level of perceived corruption. The

2012 TI scale rates Bosnia as somewhat more honest, at only 72nd in corruption;

but in the last year, perceived corruption has risen sharply, as one of the main

complaints of rioters in that country is that the Bosnian governments

privatisation of state assets in the last year was a spectacle of gross corruption.

To be sure, the angry middle classes that are demanding change are not always

democrats, nor are they always supported by a majority of the population. In

Thailand, the demonstrators in Bangkok are seeking to overturn a freely elected

Prime Minister who clearly has support among a majority of Thais; the yellow-

shirt activists who have shut down the government are monarchists who want an

appointed leader to take over instead. In Venezuela, the Bolivarian Revolution

remains popular with those outside the urban middle classes who have benefitted

from the regimes largesse, fiscally ruinous though it may be. Even in the

Ukraine, the protesters in Kiev overturned a government that had won electoral

support from a majority of the country, though concentrated in the southeast

portion of the country

Yet, democracy in the sense of majority rule is not what people are seeking. The

middle classes in the Ukraine, Bosnia, Thailand and Venezuela are demanding

greater accountability, and are challenging regimes seen as corrupt, out of touch

and which form obstacles to a better future.

Perhaps, most important, is what these events portend for the worlds largest

democracy India. Just as in Turkey, Brazil, Thailand and the Ukraine, India is

developing an urban middle class that aspires to a better life. Yet, just like these

countries, India cannot yet provide that middle class the assurance of security

and stability. Also, like these countries, the fruits of modernisation are being very

unevenly distributed across the population, and this problem is made worse by

rampant corruption. What the people of India want, just as the angry middle

classes in these four countries do, is a government that is accountable,

responsible, and effective in moving their country further into the modern world.

Not only the coming election, but what follows this election, will determine

whether Indias democracy remains peaceful. Much hope for change is riding on

this election, but if whoever emerges as the victor does not deliver meaningful

change, and puts India firmly back on the road to rapid economic growth with a

more open and responsible government, then Indias middle classes will be angry

as well. Todays scenes from Caracas and Istanbul may then be repeated in New

Delhi before too long.

(Jack Goldstone is Hazel Professor of Public Policy at George Mason University,

U.S.)

También podría gustarte

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- RedBus TicketDocumento2 páginasRedBus TicketSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Report Front PagesDocumento5 páginasReport Front PagesSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- Email EtiquetteDocumento27 páginasEmail EtiquetteVeeraAún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Asianet SelfCare ReceiptDocumento2 páginasAsianet SelfCare ReceiptSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Os 1st Pages: Mba 2012 Sngist TopperDocumento6 páginasOs 1st Pages: Mba 2012 Sngist TopperSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- A Mandate For The UNHRCDocumento2 páginasA Mandate For The UNHRCSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Hotel Receipt Template PDF DownloadDocumento7 páginasHotel Receipt Template PDF DownloadSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- To Whom So Ever It May ConcernDocumento1 páginaTo Whom So Ever It May ConcernSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Seawater DesalinationDocumento26 páginasSeawater Desalinationchameera82Aún no hay calificaciones

- 11 Major Rebranding Disasters and What You Can Learn From ThemDocumento18 páginas11 Major Rebranding Disasters and What You Can Learn From ThemSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- 12 Little Known Laws of KarmaDocumento4 páginas12 Little Known Laws of KarmaSarath P Babu100% (1)

- Organization Studys Ayur by LijinDocumento71 páginasOrganization Studys Ayur by LijinSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Hotel Receipt Template PDF Download PDFDocumento1 páginaHotel Receipt Template PDF Download PDFSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Different Types and Kinds of Mutual FundsDocumento3 páginasDifferent Types and Kinds of Mutual FundsSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- Women Entrepreneurs To Be Promoted AsDocumento3 páginasWomen Entrepreneurs To Be Promoted AsSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- International Women EnpowermentDocumento5 páginasInternational Women EnpowermentSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- First in India (General Knowledge)Documento3 páginasFirst in India (General Knowledge)Sarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- MBA Syllabus 2012Documento84 páginasMBA Syllabus 2012NathirshaRahimAún no hay calificaciones

- 10 Ways To Build Self ConfidenceDocumento4 páginas10 Ways To Build Self ConfidenceSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Methodology, Aug 2012 Question PaperDocumento2 páginasResearch Methodology, Aug 2012 Question PaperSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- TCC Summer Os ReportDocumento90 páginasTCC Summer Os ReportSarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- SSC CGL 2014 Exam Age Limit Changes and Application Deadline ExtendedDocumento1 páginaSSC CGL 2014 Exam Age Limit Changes and Application Deadline ExtendedAshish MishraAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Methodology Question Paper MG UniversityDocumento1 páginaResearch Methodology Question Paper MG UniversitySarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Mis Mba Full NoteDocumento41 páginasMis Mba Full NoteShinu Joseph Kavalam83% (6)

- Mis Mba Full NoteDocumento41 páginasMis Mba Full NoteShinu Joseph Kavalam83% (6)

- Organizational Study Report at Travancore Cochin ChemicalsDocumento59 páginasOrganizational Study Report at Travancore Cochin ChemicalsSarath P Babu100% (4)

- Lesson 01Documento6 páginasLesson 01Anjum MushtaqueAún no hay calificaciones

- Analyzing Capital Structure of Tesco and SainsburyDocumento3 páginasAnalyzing Capital Structure of Tesco and SainsburySarath P Babu100% (1)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- May2 27Documento57 páginasMay2 27Sarath P BabuAún no hay calificaciones

- 20 Residential Lafarge Gypsum Board Echobloc BrochureDocumento7 páginas20 Residential Lafarge Gypsum Board Echobloc BrochureSajed LyndAún no hay calificaciones

- Revitalizing Agriculture in MyanmarDocumento64 páginasRevitalizing Agriculture in MyanmarKo Ko MaungAún no hay calificaciones

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- International Journal of Behavioral Science (ISSN: 1906-4675)Documento112 páginasInternational Journal of Behavioral Science (ISSN: 1906-4675)Ijbs JournalAún no hay calificaciones

- The Iron LadiesDocumento4 páginasThe Iron Ladiescjparas27Aún no hay calificaciones

- Researchspu, 13 Thanaporn KariyapolDocumento13 páginasResearchspu, 13 Thanaporn KariyapolSu MonsanAún no hay calificaciones

- CM 3: Language-In-Education Policy 2: Leps of Southeast Asia and Common Issues and ChallengesDocumento140 páginasCM 3: Language-In-Education Policy 2: Leps of Southeast Asia and Common Issues and ChallengesAskin Dumadara VillariasAún no hay calificaciones

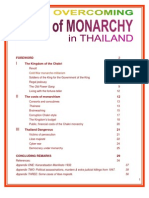

- Overcoming Fear of MonarchyDocumento61 páginasOvercoming Fear of MonarchyJunyaYimprasert100% (2)

- Thailand: Temple of The Emerald BuddhaDocumento7 páginasThailand: Temple of The Emerald BuddhaSukhuman JanputtipongAún no hay calificaciones

- Wanni W. Anderson (Editor), Robert G. Lee (Editor) - Displacements and Diasporas - Asians in The Americas (2005, Rutgers University Press)Documento310 páginasWanni W. Anderson (Editor), Robert G. Lee (Editor) - Displacements and Diasporas - Asians in The Americas (2005, Rutgers University Press)yangjiadi liuAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Sir Cecil FJ DormerDocumento28 páginasFinal Sir Cecil FJ DormerAaronDormerAún no hay calificaciones

- Southeast Asian Music and Arts Lesson PlansDocumento7 páginasSoutheast Asian Music and Arts Lesson PlansRutchelAún no hay calificaciones

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Thailand Medical Hub: Impacts On Thailand Medical Industry: Anongnat Wangwatthaka Thammasat UniversityDocumento19 páginasThailand Medical Hub: Impacts On Thailand Medical Industry: Anongnat Wangwatthaka Thammasat UniversityjwangwatthakaAún no hay calificaciones

- German Connection and The Establishment of The First Military Youth Movement in ThailandDocumento25 páginasGerman Connection and The Establishment of The First Military Youth Movement in ThailandDogeAún no hay calificaciones

- Indian Foreign Postal Rates 1957-2019Documento33 páginasIndian Foreign Postal Rates 1957-2019Abhishek Bhuwalka100% (1)

- Evans Et Al - Deviant Behavior 2000 PDFDocumento15 páginasEvans Et Al - Deviant Behavior 2000 PDFAlejandro CRAún no hay calificaciones

- (123doc) - Tape-Scription-Noi-Dung-Phan-Nghe-1Documento1 página(123doc) - Tape-Scription-Noi-Dung-Phan-Nghe-1Hà TrangAún no hay calificaciones

- Thailand Traditions and BeliefsDocumento6 páginasThailand Traditions and Beliefsapi-316342033100% (1)

- TCCC Voyageur July 2012Documento16 páginasTCCC Voyageur July 2012ThaiCanadianAún no hay calificaciones

- Guide - Mistine Direct Selling in The Thai Cosmetics MarketDocumento25 páginasGuide - Mistine Direct Selling in The Thai Cosmetics MarketThox Sic100% (1)

- Asia Pacific Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index April 2019Documento28 páginasAsia Pacific Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index April 2019Monique AdalemAún no hay calificaciones

- Contact chemical companies in ThailandDocumento14 páginasContact chemical companies in ThailandEric RavinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Thai KKDocumento4 páginasThai KKZainal Anuar RuslanAún no hay calificaciones

- Bestofasia AhlmoysjDocumento115 páginasBestofasia AhlmoysjAyesha LataAún no hay calificaciones

- Limbo Blue-Collar Roots White - Collar Dreams 2Documento6 páginasLimbo Blue-Collar Roots White - Collar Dreams 2api-662061634Aún no hay calificaciones

- Advancing Climate Resilience in ASEAN: MARCH 2020Documento36 páginasAdvancing Climate Resilience in ASEAN: MARCH 2020Lutfi ZaidanAún no hay calificaciones

- VJC Prelim H2 P1 QPDocumento7 páginasVJC Prelim H2 P1 QPFanny ChanAún no hay calificaciones

- Thai Course EnglishDocumento6 páginasThai Course EnglishpaucasteAún no hay calificaciones

- Master Plan For Automotive IndustryDocumento109 páginasMaster Plan For Automotive IndustryAvilash100% (1)

- Ulangan Descriptive TextDocumento3 páginasUlangan Descriptive TextYusrizal RusliAún no hay calificaciones

- Tourism in Bangladesh Problems and ProspDocumento10 páginasTourism in Bangladesh Problems and ProspShanto ChowdhuryAún no hay calificaciones

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,De EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (69)

- Can't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeDe EverandCan't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentDe EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (6)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziDe EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (157)

- High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingDe EverandHigh-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingAún no hay calificaciones

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfDe EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (36)

- The Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoDe EverandThe Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (10)

- The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyDe EverandThe Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Black Detroit: A People's History of Self-DeterminationDe EverandBlack Detroit: A People's History of Self-DeterminationCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (4)