Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

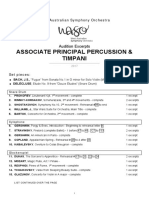

20 Tips On Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts

Cargado por

sebygavril0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

21 vistas5 páginas20 Tips on Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts TXT

Título original

20 Tips on Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts TXT

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

TXT, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documento20 Tips on Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts TXT

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como TXT, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

21 vistas5 páginas20 Tips On Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts

Cargado por

sebygavril20 Tips on Creating Realistic Sequenced Drum Parts TXT

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como TXT, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 5

CREAZA SECVENTE DE TOBE REALISTIC

CREATING REALISTIC SEQUENCED DRUM PARTS

Music mythology has it that real drummers are illiterate, beer-swilling

louts with about as much musicality as a dead dog. Nevertheless, it

can be hard to find an acceptable substitute. Sam Inglis offers a

few pointers.

Many SOS readers would rightly argue that the great advantage of sequenced,

electronic drums is that they don't force you to use 'realistic' drum patterns o

r

sounds. Much dance music, for instance, is built around incredibly fast, precise

patterns and sounds which bear only the loosest relation to anything you can

actually produce by hitting a stretched skin with a wooden stick. The ability to

produce rhythms through programming, layer by layer and step by step,

certainly offers great scope for the imagination and freedom from the technical

and sonic limitations imposed by having to play and record real drumming.

Nevertheless, it's often the case that the sound and feel of a real drum part is

required, and circumstances - time, space, lack of facilities or lack of a

drummer - force people who don't play the drums themselves to knock

something up on a sequencer. And though a sequenced part will never be a perfect

imitation, there are a

number of things you can do to make it sound more convincing.

1. Remember the physical limitations to which real drummers are subject. Obvious

ly, individual

drummers have only two arms and two legs, and are therefore only 'four-note poly

phonic' in

synth-speak - but there are also other restrictions on what is physically possib

le. Many typical rock

and pop rhythms incorporate a steady eight- or 16-to-the-bar hi-hat or cymbal rh

ythm. Above a

certain tempo, this will necessarily involve using both hands, usually playing a

lternate notes, so it's

important to think about which hand is doing what; you can't hit the hi-hat at t

he same time as the

snare or crash cymbal, for instance, if you're using both hands to keep up a ste

ady rhythm on the

hi-hat - see example 1, on page 70.

2. For the same reason, there are certain sounds which can't be combined realist

ically in the same pattern. You

can't switch instantaneously between brushes and sticks, for instance, or betwee

n using a normal hi-hat and

one with a tambourine clipped to the top. Sticks can be used to produce rimshots

, but brushes and beaters

can't, so it would be unusual to mix rimshots and brushed snare. Nor is it commo

n to combine hi-hat and ride

cymbal in the same pattern - they're usually set up on opposite sides of a drum

kit. You wouldn't usually do loud

crashes on the same cymbal in quick succession, either; if you want successive c

rashes, use two different

cymbal sounds.

3. Bear in mind that the force with which drums are struck will not be constant.

To a certain extent,

there will be random variation in the velocity of each hit, but there will also

be more predictable

variations. In pop and rock drumming, for instance, the first beat of the bar is

often emphasised,

while reggae rhythms are characterised by a heavier third beat. There are also p

hysical limitations on

how hard you can strike a drum: beats played in quick succession will tend to be

quiet, since you

can't raise the sticks as high, or get so much travel with the bass drum pedal,

between hits.

4. Also, don't ignore dynamics within the song. In dance music, the drums are of

ten compressed to the point

where they are totally even in volume throughout, and any dynamic changes are ef

fected by simply dropping out

parts of the rhythm. Real drummers, however, use crescendos and other dynamic ef

fects to add feel to a track;

often, for instance, they will build up the volume going into a chorus.

5. Use sounds which are appropriate to th

e dynamic level of

a particular drum sequence. Some percussi

on instruments,

like crash cymbals, are virtually impossi

ble to play quietly,

while others, like rimshots, bongos and h

andclaps, are

inevitably relatively quiet. A sequenced

full-on drum assault

will thus sound a little false if it is b

ased around huge,

reverberating rimshots or triangles.

6. Use only percussion instruments which

are appropriate to the

style of music you're trying to emulate,

and remember that most

real drumkits actually contain a very lim

ited number of drums. Not

many rock drummers would have wind chimes

, timbales, tablas or

claves in their standard kit; similarly,

if you're aiming for a '60s pop

feel, that 808 snare probably won't be a help. Few drumkits feature all of the h

uge range of toms found in many

synth drum sets - it's often best to choose two or three and use only those. Als

o, be careful when reproducing

drum parts played on brushes: some synths' so-called 'brush' sets actually repla

ce only the snare samples with

brushed sounds, and don't bother to provide brushed samples of cymbals or toms.

7. It's one thing to have the feel of a pattern in your mind: however, it's much

harder to analyse the

slight timing variations that produce that feel. The best way to capture 'feel',

therefore, is to play the

parts into your sequencer, from a keyboard or other controller, in real time. St

art with the two most

important - usually the bass drum and snare - in a single pass. Playing the drum

s well is, like most

instruments, difficult, and requires a lot of learning. However, it's not hard t

o use two fingers to bash

out a basic rhythm, and doing so makes it much easier to capture the elusive 'fe

el' of a real drum

part. And the beauty of sequencing is that you can correct any mistakes afterwar

ds.

8. If you're not sure what sort of feel your drum part should have, or you can't

seem to get it right by just recording

to a click track, remember that you don't have to record the drums first. If you

r song centres around a particular

piano or bass riff, for instance, you could try recording that into your sequenc

er first and add the drums later.

Being able to hear the important instrumental parts is very useful for deciding

what kind of rhythm will or won't

work.

9. If you do need to edit the patterns you've entered, avoid snap to grid or sim

ilar functions. It's all too

easy to end up not only correcting mistakes, but also the timing variations that

are responsible for

the 'feel' of the part.

10. Though editing can be used to remedy mistakes or really sloppy timing, there

's

little point in painstakingly bashing out your rhythms in real time if you're th

en going

to quantise away all the variations. If you must quantise, leave a fairly wide m

argin

so that only really late or early beats are corrected.

11. Bear in mind that a lot of real drumming styles actually depend on

consistent deviations from theoretically accurate timing. Sometimes this is

quite obvious, as in the case of heavy syncopation or 'swing', which

imposes a triplet feel on a four-beat rhythm, but it can be much more subtle.

For instance, playing slightly ahead of the beat, particularly on the first and

third beats of a four-beat bar, is a common device used to add urgency to a

rhythm, and is characteristic of much disco, pop and country drumming. In

other genres like the blues, by contrast, drummers sometimes deliberately delay

the 'off' beats to

create a laid-back feel.

12. Don't simply record a one- or two-bar sequence and then repeat it throughout

the entire song. Even if you

want to have the same drum pattern all the way through, record it several times

and mix the different versions

up. Each version you record will have slightly different dynamics and timing var

iations, and the variety will help to

reproduce the looser feel of a real drum track and implement some of the dynamic

changes I've already

mentioned.

13. Keep it simple. With today's sequencers and multitimbral sound sources, it's

easy to over-egg the

rhythmical pudding, either by adding improbable numbers of virtual tambourine, s

haker and triangle

players, or by programming intricate rhythms and fills where most real drummers

would exercise

self-restraint (or lack of ambition!).

14. Listen to drumming on records to pick up the sort of patterns and fills that

get used in a particular musical

style. Careful listening can make you realise that your assumed ideas about a pa

rticular style of drumming are

actually quite wide of the mark. For instance, it's very easy to get into the ha

bit of automatically plonking a heavy

kick drum on the first beat of every bar - but there are a number of styles, not

ably reggae and jazz, in which the

bass drum is often not played at all on the first beat (see example 2, on page 7

0).

15. Learn to read drum notation (if y

ou already read

music, it's dead easy - see box oppos

ite) and look at

transcriptions in drumming magazines

and books; the

more you know about playing the drums

, the more

accurately you'll be able to program

realistic drum

patterns.

16. Synth and drum machine sounds are

usually made using

samples of each instrument in isolati

on. Recording a real

drumkit is a different matter, howeve

r; overhead or room

mics are always used (usually in conj

unction with close mics

on individual drums) to pick up not o

nly cymbals and toms,

but the sound of the whole kit, along

with a certain amount of

room ambience. Programmed drum parts

in their raw state

can sound sterile and disjointed by c

omparison, because

they lack this element. You can avoid

this to a certain extent

by taking care with panning - don't p

an anything too hard left

or right, and keep the bass drum in t

he centre of the field. You

can also experiment with putting a ro

om reverb on the drums

to make them sound more coherent.

17. Beware, however, that synth progr

ammers have a

tendency to swathe every drum sound i

n a blanket of

reverb. This may sound impressive when you're trying the instrument out in a mus

ic shop, but again,

doesn't always represent the pinnacle of realism. Massive reverb does suit some

styles of drumming

(Def Leppard anyone?) but by no means all - and where it is used to excess on re

al drums, its effect

is often to make them sound more artificial. Experiment with different depths an

d styles of reverb

until you find something that sounds right.

18. Standard drum kit sound sets, particularly

those conforming to the General MIDI drum

map, suffer certain persistent problems.

Perhaps the most obvious of these is the use

of only three different hi-hat sounds - open,

closed and pedal - when real drumming

makes use of a continuous range of sounds

from quiet to soft, from tight closed to open. A

common device for creating effective build-ups

into loud sections, for instance, is to open the

hi-hat gradually over a bar or two, moving from a tight 'tsk' to a looser, splas

hy sound - which progression can't

really be reproduced using only single open and closed sounds. There are also no

ticeable sonic differences

between a hi-hat struck with the tip of the stick and with the shaft; real drumm

ers do both, often alternately.

Getting hold of a more comprehensive set of hi-hat samples, then, is an effectiv

e way to improve the authenticity

of your sequenced drumming. You could even consider miking up and playing a real

hi-hat over your sequenced

kick and snare pattern.

19. Another problem with many sampled sound sets is that they do not reflect the

ways in which the

sound of real percussion instruments varies depending on the force with which th

ey're struck.

Giving a hi-hat or a cymbal a heavy bash produces a sound which is not only loud

er than a gentle

tap, but quite different in timbre; the same is true of snares and other drums.

If your sound set merely

responds to velocity by making the sounds louder or quieter, you need to be care

ful how you use

them (for instance, avoid trying to reproduce quiet cymbal washes if you only ha

ve samples of loud

crashes).

20. Don't be afraid of changes in tempo. Real drummers speed up and slow down -

sometimes deliberately,

sometimes not - and these tempo changes can help to give a track a more organic

sound. Some tempo

changes are very obvious, such as rallentando (slowing down towards the end of a

song) and segues between

slow and fast sections of a song. Others, however, are more subtle: it's quite c

ommon for drummers to speed

up slightly going into a chorus, for instance. Some classic recordings even feat

ure a gradual increase in tempo

over entire sections or, in extremes, over the entire song - a well-known recent

example is Pulp's 'Common

People'. It may take a little extra sequencing to implement tempo changes in mid

-song, but the results can be

very effective.

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Drummer Beginners PacketDocumento31 páginasDrummer Beginners PacketMark Abola100% (11)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- Whre The Black Hawk Soars - R. W. SmithDocumento79 páginasWhre The Black Hawk Soars - R. W. SmithTiago urbano100% (4)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Camel Audio Alchemy VST ManualDocumento160 páginasCamel Audio Alchemy VST Manualrocciye100% (5)

- Musician's Handbook - 2016Documento132 páginasMusician's Handbook - 2016debikson0% (1)

- The Drum Mixing GuideDocumento25 páginasThe Drum Mixing GuideMirkoGMazzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Yamaha PSR E423 EnglishDocumento28 páginasYamaha PSR E423 Englishrajibranjan7338Aún no hay calificaciones

- Null 5 PDFDocumento51 páginasNull 5 PDFphilip kanzaAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- Highway SoundscapesDocumento24 páginasHighway Soundscapescesar perisAún no hay calificaciones

- The Classical PeriodDocumento30 páginasThe Classical PeriodCring Cring RamosAún no hay calificaciones

- Smartmusic Softsynth Percussion Midi MapsDocumento3 páginasSmartmusic Softsynth Percussion Midi MapsSentido Común Alternativo SCAAún no hay calificaciones

- 40 HighSchoolCadetsDocumento84 páginas40 HighSchoolCadetsMareina Harris100% (1)

- Havendance: David R. HolsingerDocumento42 páginasHavendance: David R. HolsingerBrian RepetaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ryan George: Fornine MusicDocumento22 páginasRyan George: Fornine MusicalexAún no hay calificaciones

- Associate Principal Percussion and Timpani Excerpts 2017Documento124 páginasAssociate Principal Percussion and Timpani Excerpts 2017chaohua fu100% (2)

- Red Rock Mountain PDFDocumento34 páginasRed Rock Mountain PDFtrevorAún no hay calificaciones

- ASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDocumento11 páginasASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDanny_Grafix_1728Aún no hay calificaciones

- ASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDocumento11 páginasASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDanny_Grafix_1728Aún no hay calificaciones

- ASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDocumento11 páginasASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDanny_Grafix_1728Aún no hay calificaciones

- AbcDocumento4 páginasAbcsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Soundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkerDocumento6 páginasSoundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkersebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Soundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkerDocumento6 páginasSoundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkersebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Soundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkerDocumento6 páginasSoundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkersebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Soundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkerDocumento6 páginasSoundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkersebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Soundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkerDocumento6 páginasSoundcard Recording FAQ's Answered by Martin WalkersebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordDocumento4 páginasWhat The Hell Is Mixing by Nigel LordsebygavrilAún no hay calificaciones

- Classifications of InstrumentsDocumento14 páginasClassifications of InstrumentsJizza che MayoAún no hay calificaciones

- Cym Catalog 14Documento41 páginasCym Catalog 14JuanLuisGuerraBaltazarAún no hay calificaciones

- EDQ by Oparachukwu Test IDocumento32 páginasEDQ by Oparachukwu Test IMikeson100% (1)

- EXZ007 "EXZ Orchestra" Sound ListDocumento10 páginasEXZ007 "EXZ Orchestra" Sound ListRobert PatkoAún no hay calificaciones

- Brass Band InstrumentationDocumento20 páginasBrass Band InstrumentationJelle Visser100% (1)

- Daniel Denis MD2010Documento5 páginasDaniel Denis MD2010Clint HopkinsAún no hay calificaciones

- Cine PercDocumento154 páginasCine PerchogarAún no hay calificaciones

- Cymbal Technique GuideDocumento3 páginasCymbal Technique GuidescooterbobAún no hay calificaciones

- EZX KeysDocumento1 páginaEZX KeysRadio MondoAún no hay calificaciones

- TD-6 6VDocumento21 páginasTD-6 6VBastiaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra Gemma New, Music Director: Announces The Following VacancyDocumento5 páginasHamilton Philharmonic Orchestra Gemma New, Music Director: Announces The Following VacancysandraAún no hay calificaciones

- AT-350C Version 2 Manual: New Features and FunctionsDocumento16 páginasAT-350C Version 2 Manual: New Features and Functionsandre_tfjrAún no hay calificaciones

- VI DL JazzDrums Patch Matrix Preset v5Documento42 páginasVI DL JazzDrums Patch Matrix Preset v5Nils Van der PlanckenAún no hay calificaciones

- Coleman - Instrument Design in Selected Works For Solo Multiple Percussion PDFDocumento66 páginasColeman - Instrument Design in Selected Works For Solo Multiple Percussion PDFMarceloAún no hay calificaciones

- Veronica Kongs 2007Documento93 páginasVeronica Kongs 2007kingtigerAún no hay calificaciones

- Product Catalogue 2008Documento17 páginasProduct Catalogue 2008plsdAún no hay calificaciones