Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

New Mithaq Eng Tcm10-8830

Cargado por

waniasimDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

New Mithaq Eng Tcm10-8830

Cargado por

waniasimCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

2

:

2

ADCB Master Key to Islamic

Banking and Finance

C o n t e n t s :

Introduction

Common properties of Islamic financing modes

The Generic Islamic Modes

Salient Features of Variable Return Modes

Salient Features of Fixed Return Modes

Murabaha to the Order of Purchaser (MOP)

Ijara, the Islamic Lease Finance

Salam, an Islamic Forwards Mode

Istisnaa, an Industrial arm of Islamic finance

Conclusion

This booklet is the first cultural product of a special public awareness programme on Islamic finance

organized by Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank (ADCB) for the benefit of its highly valued clients. ADCB is

proud to take the lead in this cultural campaign, the first of its kind in the Emirates, with the objective

to enlighten the public on the ethical and practical appeal of Islamic banking and investment ser vices.

Believing that public awareness is necessar y for the breaking of new grounds in the provision of Islamic

finance, the ADCB is already committed to the gradual but steady introduction of authentic Islamic

banking products. We believe that public awareness on the principles of Islamic finance leads to better

customer relationships, and hence augurs for brighter and wider horizons vis--vis the growth of Islamic

finance.

As the title implies, the Master Key to Islamic Banking and Finance 1 is intended to set the scene for

its readers to appreciate the potential capacity of Islamic finance in terms of accommodating modern

banking needs. At this stage, basic questions are addressed about Islamic finance, why it is needed,

and how it fundamentally differs from conventional banking. This is done in terms of five basic questions

which are carefully chosen to address the most common queries which tend to be publicly raised about

the case for Islamic banking. This preliminar y background will, then, be supplemented by the Master

Key to Islamic Banking and Finance 2 which is intended to lay down the basic foundation of Islamic

modes of financing.

Having set the scene and laid the basic foundation of Islamic finance, the programme will proceed to

more practical questions of how banking needs can be provided in the Islamic way. It is the objective

of for thcoming booklets, to be produced later this year, to handle more technical issues in relation to

retail, corporate, and investment banking. The programme is addressed to a wide spectrum of potential

audience who wish to understand the relevance of Islamic finance to the ever rising challenges of the

modern world. Retail banking clients, corporate executive managers, institutional investors, professional

bankers, government officials, and academic students may all benefit from ADCBs planned series.

Introduction (1) Why Islamic banking and finance?

It is the mechanism of lending and borrowing at the interest-rate which triggered Muslims search for

an alternative financial order. Islamic finance owes its driving force to a solid consensus amongst

contemporar y Shariah scholars that the charging of interest on borrowed money is a breach of the

Quranic prohibition of usur y (riba). It is well known that similar prohibition existed in the earlier scriptures

of Judaism and Christianity.

In the Quran, it is stated that God has permitted trade and prohibited usur y (Quran 2:275). The

prohibition of usur y is stated in the strongest terms whereby Muslims are warned of war from God

and His Messenger if they fail to abide by this order (Quran 2:279). The tradition (Sunnah) of the

Prophet (peace be upon him) came to reasser t this Quranic prohibition and to elaborate on various

manifestations of usur y.

Money lending at a (fixed) price was practiced in many ancient civilizations though under severe ethical

criticisms by philosophers and religious leaders. The famous Greek Philosopher, Aristotle, developed the

argument that money is sterile and therefore it should not command a return for its own sake. In other

words, money can only function as a medium of exchange, to facilitate trade in goods and ser vices.

It is notewor thy that the contemporar y Western banking system emerged from a historical battle against

the Christian Church on the issue of usur y. It eventually benefited from a groundbreaking verdict by the

Protestant Bishop, John Calvin, who argued that money lending for productive activities was permissible

since it differed from the biblical usur y. Yet, when related to the Quran and the Prophets Sunnah, this

verdict was not shared by the majority of Muslim scholars. It explains why Muslims have conscientiously

shouldered the responsibility of reviving the human ethics of interest-free financing.

This booklet represents the second cultural product relating to ADCBs public

awareness initiative, which aims to portray the ethical and practical dimensions

of Islamic nance. It follows ADCBs rst booklet, Master Key to Islamic Banking

and Finance 1, which sought to provide some key fundamental answers to

the broad question of why Islamic nance is needed, and how it fundamentally

differs from conventional banking. The previous booklet presented a brief

introductory expose of Islamic banking outlining the most basic functions that

Islamic nancial institutions may perform and emphasising the condition that

all Islamic banking activities must always be in accordance with Shariah (i.e.

Islamic Law) which strictly prohibits usury (Riba).

In reality, the eld of activity for Islamic banks is much wider than simple bank

intermediation. Taking the subject forward, the present booklet seeks to, (inter

alia), explain the actual role that Islamic banks perform in practice, based

on the concept that the Islamic bank can play the roles of both investment

manager (as a Mudarib or Musharik, etc) as well as of the investor (owner of

funds i.e. Rabb al Maal).

Also among the objectives of the current booklet Master Key to Islamic Finance

2 is to outline the various alternative nancing modes which are most often

used in Islamic nance. This will pave the way for a more technical treatment

of retail, corporate and investment banking which will be the subject matter of

forthcoming editions in ADCBs present series of Islamic nance booklets.

ADCBs drive to promote awareness and provide information about Islamic

business, nance and banking is meant to be inclusive, and is aimed at

reaching a wide target audience with varying degrees of familiarity with,

and an interest in, Islamic nance. It seeks to assist all those who want to

understand the relevance of Islamic nance to the ever increasing challenges

of the modern nancial world. As such, it is hoped that bankers, corporate

managers, institutional investors, government ofcials, students of economics

and nance and many others would all be able to benet from this series of

Islamic nance booklets.

I

n

t

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

Common properties of

Islamic nancing modes

ADCB is committed to the gradual introduction of authentic Islamic banking

products. We believe such an approach can take place effectively and

sustainably only when coupled with a sound education and general awareness

programme on the principles of Islamic nance. Harnessing the true potential

of Islamic nance and reaping the full range of fruits and benets that it has to

offer would only be achieved through a sound understanding of the essential

ideals that are embodied in this discipline.

Prior to reviewing the individual properties of each of the different Islamic modes

of nancing, as a prelude it is well worth looking at some generic properties

shared by all of them. The gist of the rst booklet, Master Key to Islamic Banking

and Finance 1, was to highlight that the essential factor distinguishing an

Islamic banking system from a conventional banking framework relates to the

concept of money itself. Islamic modes of nancing view money simply as a

medium of exchange rather than as an object of trade, and thus money is not

allowed to beget more money. However, in the case of conventional nance,

money itself is the basis of numerous nancial transactions such as loans of

various kinds, such that the initial sum of money loaned serves as the basis on

which the conventional bank makes further monetary prot (typically in the form

of interest). This key distinction gives rise to certain features which apply to all

modes of Islamic nancing, and are listed as follows:

Common question: The fact that money in Islam is viewed exclusively as a

medium of exchange results in all potential Islamic banking customers who

seek nancing, being asked the question: what do you need the money for?.

Thus, it is a condition that the Islamic bank should understand and participate

in the underlying business activity which the nance is to be used for. Although

conventional banks may ask a similar question, this is usually only for purposes

of classication or analysis.

In the Islamic paradigm, the response to this question will directly determine

the nancing mode used, giving rise to the view that Islamic nance is better

suited to satisfy the real economic needs of customers for money, as opposed

to simply selling money for more money as is the conventional way.

Common source of jurisprudence: Islamic modes of nancing are all rooted in

the jurisprudential sources of Islam, the primary ones being the Quran and the

Sunnah (prophetic example). It is these sources which outline what is permissible

to invest in and what is not, and which requires transactions involving interest,

gambling and excessive uncertainty to be shunned. For example, the Quranic

verse God has permitted trade and forbidden usury sets the rationale for the

jurisprudence of economic exchange (qh al-beyou) in Islam. Throughout this

booklet, we will see that it is the adaptation of Islamic Jurisprudence which

determines the validity of nancial products and modes of business.

Common measure of nancial return: Islamic modes of nancing share the

common property of generating legitimate trade prot in conformity with

the common Shariah maxim, al-kharaj-bi-al-daman which means prot (is

justied) with risk. The difference between the prot rate associated with

trade and the forbidden usury was already noted in Master Key to Islamic

Banking and Finance 1

As mentioned earlier, Islamic banks may act as investor (by providing investible

funds) as well as investment manager. Thus, Islamic nancing modes

operated by Islamic banks may be regarded as investment modes, where

the Islamic banks aim is to nance economic or investment activities of its

clients. As an alternative activity, Islamic banks may act as an investment

manager when it receives deposits from its customers/investors, by investing

the funds received in various Shariah compliant activities itself.

At this stage it is more illuminating to focus on the investor role of the Islamic

bank, via which various nancing modes are offered to customers. Treatment

of investments is deliberately left to a special booklet which will be released in

the near future. The above common properties provide a useful framework for

introducing the different modes of Islamic nancing. Therefore:

i) Regarding the question what do you need the money for?, each mode of

nancing will be shown to satisfy a real economic need;

ii) Regarding the underlying jurisprudence, each of the modes of nancing

will also be seen to invoke particular rules pertaining to their deduction

and applicability;

iii) Regarding the distribution of nancial return, each of these modes will be

allied with a corresponding assumption of risk, justifying the returns.

Depending on the economic activities being envisaged, customers may

respond to the common question what do you need the money for in ve

different ways:

1. To acquire needed capital for a particular business activity.

2. To purchase particular goods already available in the market.

3. To benet from the service/use of existing durable assets (e.g.

equipments, buildings etc) for xed periods of time.

4. To nance the production of natural products (agricultural, mining etc).

5. To nance the manufacturing of industrial products (equipments, buildings

etc).

To satisfy the rst response Islamic banks may offer customers one of

two possible modes of nancing: Mudaraba or Musharaka. The former is

represented by a two-party contract involving the bank as the provider of capital

Generic Islamic

modes of finance

(Rabb al-Mal) and the customer as manager (Mudarib) in the agreed trade

activity. In the latter, the customer and the bank both contribute part of the

capital, and so the two parties enter a partnership (shirka). As a result of this

partnership, they share the prots (and losses) generated by the business, as

well as the management responsibilities.

The main contractual properties of Mudaraba or Musharaka will be presented

later on in this booklet in the section Salient Features of Variable Return

Modes since the prot rate in these two modes can take any value depending

on uncertain market conditions. In contrast, the second, third, fourth and fth

responses are best satised through the offering of xed return nancing

modes, which are covered in the section Salient Features of Fixed Return

Modes.

In particular, the second response calls on banks to acquire the requisite

goods and sell the same to the customers through Murabaha.

The third response necessitates delivery of the required goods to customers,

not via sale of goods itself (raqabah), but against sale of usufruct (manfaa)

for xed periods of time through Ijara (rental/lease).

The fourth and fth responses are examples of forward sales to meet specic

needs and are based on nancing modes known as Salam, and Istisnaa.

Usually, an amount is paid upfront (this may sometimes be deferred, in case

of Istisnaa) and delivery is agreed upon on a set date.

The above ve are the generic Islamic nancing modes which characterise the

bulk of Islamic banking and nance operations commonly in practice.

These modes serve as the basis upon which new, inventive, and often complex

nancing and investment structures are being researched and developed

continually, as part of the recent and continuing surge in innovation in the

Islamic nancial industry.

Other than the aforementioned ve generic modes, there are also other Islamic

modes of nance in practice which are used somewhat less frequently; these

include Investment Agency (wakala l Istithmar), as well as three modes which

relate specically to agricultural business deals, namely Muzara, (),

Mugharasa (), Musaqa ().

We will now elaborate on the special features for each of the generic modes

listed above.

Mudaraba, as briey introduced above, involves the bank as the capital

provider (Rabb al-Mal) and the customer as manager (Mudarib) for the agreed

trade activity.

At the core of any Mudaraba contract, there are four basic conditions:

Prot, when realised, has to be shared between the two parties in

accordance with a prot-sharing ratio stipulated at the time of the signing

of the contract. Losses, in case they arise, would have to be borne

entirely by the Rabb al-Maal (i.e. the bank) while the Mudarib only loses

his management effort.

The Rabb al-Maal cannot interfere in the day-to-day management of the

Mudaraba. S/he can however restrict and dene the possible elds of

economic activity for the Mudarib. This provision, however, has to be made

clear at the outset within the initial Mudaraba contract.

The Mudarib has a hand of trust (yad amana) in the management of

Mudaraba capital, which means s/he is expected to work to the best of

Salient features of

variable return modes

their ability. It means there cannot be a guarantee of capital or prot to

the Rabb al-Maal.

Loss of capital can be guaranteed by the Mudarib only when such loss is

proven to be the result of mismanagement or delinquency of the Mudarib

(mentioned above); or where such losses result from a breach of contract,

for example investing in a eld that falls outside the prescribed/specied

elds of economic activity.

Thus to elaborate further, the most salient features of Mudaraba are that,

rstly, the Islamic bank plays the role of the investor and does not participate

in the management of the business project, and secondly, while the prot

distribution ratio for the Mudarib and the Rab Al Mal is clearly pre-dened, the

actual amount of prot remains uncertain.

As can be expected, what attaches substantial uncertainty and risk to the

Mudaraba prot rate is the undened range of potential trade transactions

and operations which the Mudarib can freely practice in the management of

the Mudaraba capital. Hence, many Islamic banks, precisely in order to control

this risk, resort to the restriction of the Mudaraba contract such that it relates

to a pre-assigned set of well structured trade dealings in accordance with

Shariah.

Musharaka carries a similar uncertainty with regards to the actual prot amount,

as with a Mudaraba. The key difference is that the partnership is characterised

by a sharing in both the capital and management responsibilities; therefore, in

a Musharaka the customer is the banks partner investor, and the bank also

acts as joint investment manager, both aspects being unlike in a Mudaraba.

Moreover, the fact that part of the capital is contributed by the customer leads

to special provisions in the Musharaka contract which can be summed up in

the following:

Partners in a Musharaka all have the right to engage in the day-to-

day management of the Musharaka capital, except where one party

deliberately gives up this right to the other partner(s). Many Islamic banks

prefer to waive their rights of Musharaka management in favour of their

customers on the grounds that the latter are more qualied to run their

own businesses.

Prot, when realised, is usually shared by the partners in proportion to

their capital contributions (i.e. on a pro rata basis). Yet in the context of

Islamic banking, it is possible for one party to get a proportionately bigger

share of prot if this is to the mutual agreement of both parties. Loss,

however, has to be strictly shared on a prorata basis.

No party can be held liable to guarantee capital or prot to another party.

Only where mismanagement and delinquency are proven or where a breach

of the Musharaka contract is committed, can the party so charged be held

liable to guarantee capital contributions to other parties.

Prot (or loss) cannot be prioritised within the Musharaka contract. No

party (or group of parties) can be preferred to others in terms of prot

distribution or loss allocation, and no pre-xed return can be promised to

any. The fact that all parties have to be fairly treated as per the pre-agreed

prot distribution mechanism underscores prot & loss sharing (PLS) as

the core concept of Musharaka.

As in Mudaraba, it is the undened range of potential trade transactions in

Musharaka which increases the risk factor associated with the returns. To

control the risk of return in Musharaka, many Islamic banks limit the contract

to well-structured, pre-specied trade dealings which conform to Shariah.

Moving on to the next section, it will be observed that the outright adoption of

xed return modes seems to have emerged as the more direct way for Islamic

banks to mitigate risk

Being deposit-taking institutions, Islamic banks act under social, ethical and

religious responsibilities to guard depositors money and investors funds

against risks which can otherwise be effectively controlled in accordance

with Shariah. This is partly reected in judicious efforts of Islamic bankers

to develop well-structured nancing and investment transactions with least

possible risks.

Reduction of banking risk can be ethically favourable from an Islamic

perspective so long as injustice is not committed to any party in this process.

Acting under keen Shariah supervision, Islamic bankers developed a range

of xed return modes with calculated risks to depositors and investors. Three

main factors tend to characterise xed return modes:

That they all focus on single packages of well-structured trade transactions

- one at a time - rather than undened pools of trade transactions which

traditionally characterise Mudaraba and Musharaka.

That xity of return originates in the xity of prices, which is an important

Shariah requirement in all exchange transactions. Utilising this jurist

property, nancial innovation in Islamic banking has made tremendous

progress over the years in the structuring of xed return modes.

That deferred prices can be higher than spot prices for goods and services

so long as sale contracts conform to Shariah conditions. This makes it

possible to dene future re-payment schedules of bank dues in terms

which reect the time factor.

1

Murabaha is perhaps the most common tool of Islamic banking. It belongs

to the class of trust sales (beyou al-amana) in Islamic jurisprudence, which

necessitate the disclosure of the original cost of goods before selling the

same to a (third) party. Thus, in a Murabaha sale Islamic banks inform the

customer of the original cost at which a good has been acquired together

with the prot or mark-up required by the bank, before selling the same to the

customer.

Banking Murabaha is more accurately described as Murabaha to the Order of

Purchaser (MOP). It is a process which starts from a banking order placed by

the customer, stating the customers intention to buy a particular good from

the bank in accordance with the principles of Murabaha, provided that the

bank acquires the good to meet his order. At this stage, it is crucially important

to make sure that the good is not already owned by the customer in one way

or other, for otherwise this would be tantamount to a conventional loan the

reason being that since no asset would be changing hands, the mark up would

then be interest.

In a nutshell, the jurisprudence of Murabaha calls upon the bank to buy the

required goods, thereby, satisfying the preconditions of possession and

acquisition of the goods prior to their sale. Once acquired, the bank would

sell the same to the customer on credit with the prot mark-up reecting the

time value of the deferred price. To make the MOP workable, there needs to be

a promise by the customer to buy the goods once these have been acquired by

the bank specically to meet his/her order. The MOP raises special concerns

about clients promise to purchase the good once it is being acquired to his

order. Without binding promises, immense damages would surely befall Islamic

Murabaha to the

Order of Purchaser (MOP)

Salient features of

fixed return modes

1

Contrary to common perception, there is concensus among Islamic scholars that it is permissible to ask for a higher sale

price if the length of the deferred time period is also greater, as long as the underlying investments are deemed Shariah

compliant, and the agreed schedule for delivery and payment is set once, and subsequently not altered.

bankers, who would then end up having heaps of unwanted scattered goods

due to failure of clients to honour their promises. For this reason, Shariah

scholars have approved binding promises as means to dispel the risks.

Binding promises, however, should not be mistaken for enforcing clients to buy

the goods as ordered. Indeed, any enforcement of this sort is sufcient to

invalidate sale contracts in Shariah perspective. The client, therefore, is free

to turn down the good if so he wishes, but the binding promise is a means to

compensate the bank against loss of capital incurred as a result.

Fixity of price is a crucial provision which limits the banks ability to adjust the

price once it has been agreed, even where the client defaults. It was made

clear in the Master Key 1 that any penalty charge due to clients default is

tantamount to riba al-Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic usury). More generally, there is no

scope for oating mark-up in line with oating interest rates. Murabaha has

proved particularly powerful in the nancing of short to medium term investments.

More elaborate structures based on provisions of agency have been developed

over the last ten years, particularly in international commodity trade.

Ijara is the Islamic banks most preferred mode in relation to long-term

nancing and investment. As briey introduced above, Ijara is a sale of usufruct

yielded by a durable asset (equipment, real estate etc) for an agreed period of

time. Similar to Murabaha, the process of Ijara starts by the clients express

intention to hire the service of a specic durable asset if it can be acquired by

the bank to the clients order.

Also in line with Murabaha, the banks ownership of the asset must be

conrmed before being sold to a third party, except that the subsequent

Ijara, the Islamic

lease nance

sale in Ijara relates to the assets usufruct and not to the asset itself.

The Ijara contract denes the customer as a lessee (mustajir) and the

bank as a lessor ( mujir) .

Since the assets usufruct can only be generated for a xed period of time,

the price of Ijara (ujra) must be expressed in terms of this nite period of

time (number of months, years, etc). The generally accepted practice of

Islamic banks is to spread the agreed price of Ijara evenly over the agreed

period of time (monthly, quarterly etc).

Since the ujra is the price of usufruct, the banks entitlement of Ijara

payments depends on the customers ability to actually use the asset during

the contracted period. This means that such an Islamic lease differs from

a conventional lease in the following respects:

1. The Lessee cannot guarantee the asset against ordinary wear and tear

as a result of use.

2. Liability remains with the Lessor with regard to technical faults unlike

a conventional lease where once the contract is signed, it is assumed

the lessee bears responsibility.

3. Depending on the technical nature of the assets, the accepted

practice among Islamic banks is to divide maintenance costs (inclusive

of cooperative insurance, Takaful costs) between the bank and the

customer, such that routine preventive maintenance is borne by the

customer while structural maintenance is borne by the bank.

Ijara-cum-sale is a common technique practiced by Islamic banks, whereby

the customer is given the option to buy the asset at a specied price most

often the assets scrap value either during or at the end of the lease period.

It is worth noting, the forbidden combining of two sales in one contract in

Islamic jurisprudence does not apply here since Ijara-cum-sale is in effect

a type of sale option which the customer may or may not exercise.

The Ijara contract has remained the focus of extensive innovation over the last

ten years. A number of more advanced structures of Ijara have subsequently

been developed, which are beyond the scope of this current booklet.

Though less commonly practiced than Murabaha and Ijara, Salam is gaining

increasing importance as an Islamic futures mode of nancing and investment.

Conventional futures involve sale contracts where goods delivery and price

payment are both deferred to a future date. This, however, is not allowed in

Islamic sales. Conventional future contracts are impermissible in Islamic

jurisprudence on the grounds of being debt-for-debt transactions.

Debt is known to arise in sale transactions through the deference of either

money or any fungible goods (items which can easily be replaced for one

another - mithliyyat e.g. wheat, rice, minerals, petroleum etc). If money is used

to buy a fungible good but the delivery of both items is deferred to a future

date, this is effectively a debt-for-debt transaction which is not allowed in

Shariah. Hence, to avoid debt-for-debt transactions, it is important that

deference of fungible goods be matched by spot payment of money. Salam

is such a mode which satises this property and it is, thus, presented as the

means to nance Islamic futures.

The hallmark of Salam is the act of spot price payment to seller of future

goods. Buyer is called capital provider (al-muslim or rabb al-salam) since

he or she has to submit the whole price in the contract session. Seller is the

Salam-taker (al-muslam elaihi) who is committed to make delivery of specic

goods to the buyer, which has to be at a specic future date, for specic

volume or weight.

Salam nancing is particularly suitable for the nancing of large scale

agricultural crops where banks provide liquid capital to clients against future

delivery of crops. In the standard practice Islamic banks would normally

close their Salam positions by entering into parallel Salam contracts. This

makes it possible for banks to sell the original Salam goods at reasonable

prot margins.

It is important, however, to conclude parallel Salam contracts independently

of original Salam contracts. It means no cross-references must exist

between an original Salam contract and the one parallel to it. This important

provision ensures that the original obligation of a Salam-taker to deliver

specic Salam goods at a future date will always remain valid regardless of

any external conditions or circumstances.

Salam is gradually becoming a vital investment mode in international

markets which involve agricultural products, petroleum products and

minerals. Millions of dollars are being invested annually through Islamic

investment vehicles in low risk Salam transactions.

Istisnaa is the industrial counterpart of Salam. In essence, it is a two-party

contract involving the maker of an industrial product (called saan) and the

demander of the product (called mustasni), such that at a future date the

former delivers to the latter a specic product (e.g. equipment, furniture,

real estate property etc) of a specic quality against payment of a specied

and agreed amount.

Istisnaa, an industrial

arm of Islamic nance

Salam, an Islamic

forward mode

At the face of it, Istisnaa may look exactly like Salam except for the nature of

the goods traded in. Yet the nature of goods makes a crucial difference in

Islamic jurisprudence. Without going into thorny jurist issues, it sufces to

realise that industrial goods, in general, do not fall into the Salam category of

fungible goods. Hence, the problem of debt-for-debt transactions should not

arise with industrial goods.

The above difference with a Salam transaction gives Istisnaa more exibility in

terms of price payment. It now becomes possible to defer part of the price,

which otherwise is strictly prohibited in Salam. Payment of price in an Istisnaa

contract may therefore be spread over any period of time that is reasonably

agreed by the two parties.

There is no wonder then that Islamic banks have successfully tapped into the

immense potential of Istisnaa contracts in nancing as well as investment

management. This brief background concerning Islamic business and

nancing modes should prove extremely useful at a later stage when we

tackle more practical issues related to retail, corporate and investment fund

management.

Although the present booklet is brief and summarised, the aim has also been

to keep it concise enough to be able to provide a satisfactory basic insight

into the modes of business nance most commonly used within the Islamic

nance industry. At a later stage we hope to tackle more industry-specic

practical issues related to Islamic banking with a focus on retail, corporate

and investment fund management.

Conclusion

También podría gustarte

- AC FAN CalculationDocumento6 páginasAC FAN CalculationSubramanyaAún no hay calificaciones

- GE Multilin Relay Selection GuideDocumento40 páginasGE Multilin Relay Selection GuideSaravanan Natarajan100% (1)

- DC Battery Bank Sizing PDFDocumento37 páginasDC Battery Bank Sizing PDFflyzalAún no hay calificaciones

- Substation Insulation Coordination Studies-Sparacino PDFDocumento42 páginasSubstation Insulation Coordination Studies-Sparacino PDFPaco Mj100% (1)

- Hoffman Heat Dissipation Document PDFDocumento6 páginasHoffman Heat Dissipation Document PDFbilgipaylasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Hoffman Heat Dissipation Document PDFDocumento6 páginasHoffman Heat Dissipation Document PDFbilgipaylasimAún no hay calificaciones

- 10 Insulation Co-OrdinationDocumento18 páginas10 Insulation Co-Ordinationdaegerte100% (3)

- Urban DesignDocumento22 páginasUrban DesignAbegail CaisedoAún no hay calificaciones

- 110 - Technical Specification 220kV Moose + Zebra WB - 10-ADocumento255 páginas110 - Technical Specification 220kV Moose + Zebra WB - 10-AwaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- 11 Distance ProtectionDocumento22 páginas11 Distance ProtectionSristick100% (1)

- What Causes Small Businesses To FailDocumento11 páginasWhat Causes Small Businesses To Failmounirs719883Aún no hay calificaciones

- Qard Hasan Credit Cards and Islamic Financial Product StructuringDocumento21 páginasQard Hasan Credit Cards and Islamic Financial Product StructuringPT DAún no hay calificaciones

- Project On SpicesDocumento96 páginasProject On Spicesamitmanisha50% (6)

- Transformer PolarityDocumento4 páginasTransformer Polarityboy2959Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Dev of Islamic Fin SystemDocumento13 páginasThe Dev of Islamic Fin SystemNadiah GhazaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Iffco-Tokio General Insurance Co - LTD: Servicing OfficeDocumento3 páginasIffco-Tokio General Insurance Co - LTD: Servicing Officevijay_sudha50% (2)

- J. R. Lucas - Three Phase TheoryDocumento19 páginasJ. R. Lucas - Three Phase TheoryQM_2010Aún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction to Wind Turbine Electrical SystemsDocumento43 páginasIntroduction to Wind Turbine Electrical Systemswaniasim100% (1)

- Introduction to Wind Turbine Electrical SystemsDocumento43 páginasIntroduction to Wind Turbine Electrical Systemswaniasim100% (1)

- Islamic Wealth Management PDFDocumento10 páginasIslamic Wealth Management PDFislamicthinkerAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsDe EverandIslamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Principles of Islamic Finance: New Issues and Steps ForwardDe EverandPrinciples of Islamic Finance: New Issues and Steps ForwardAún no hay calificaciones

- Ril JioDocumento6 páginasRil JioBizvin OpsAún no hay calificaciones

- AlMurshid Islamic Booklet 4thengDocumento12 páginasAlMurshid Islamic Booklet 4thengJusticeman AminAún no hay calificaciones

- AlMurshid Islamic Booklet 4theng Tcm10-8837Documento12 páginasAlMurshid Islamic Booklet 4theng Tcm10-8837Mrudula GummuluriAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Shari'a Concepts Governing Islamic Banking FinanceDocumento44 páginasIslamic Shari'a Concepts Governing Islamic Banking FinanceYusuf KaziAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking Ideal N RealityDocumento19 páginasIslamic Banking Ideal N RealityIbnu TaimiyyahAún no hay calificaciones

- Vol 12-2 and 13-1..mabid Al Jarhi..Universal Banking - MabidDocumento65 páginasVol 12-2 and 13-1..mabid Al Jarhi..Universal Banking - MabidMaj ImanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Chancellor Guide to the Legal and Shari'a Aspects of Islamic FinanceDe EverandThe Chancellor Guide to the Legal and Shari'a Aspects of Islamic FinanceAún no hay calificaciones

- PHD Thesis On Islamic BankingDocumento5 páginasPHD Thesis On Islamic Bankingvxjgqeikd100% (2)

- Name AQIB BBHM-F19-067 BBA-5ADocumento5 páginasName AQIB BBHM-F19-067 BBA-5AJabbar GondalAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic BankingDocumento11 páginasIslamic BankingAmara Ajmal100% (5)

- Significance.104 SairDocumento6 páginasSignificance.104 SairSyed sair SheraziAún no hay calificaciones

- IB Report BodyDocumento28 páginasIB Report BodyAyesha SiddikaAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking ProjeectDocumento76 páginasIslamic Banking ProjeectMuhammad NadeemAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking in Malaysia - Split - 1Documento9 páginasIslamic Banking in Malaysia - Split - 1ytz007163.comAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis On Islamic Banking in PakistanDocumento7 páginasThesis On Islamic Banking in PakistanBuyResumePaperCanada100% (2)

- Challenges Facing The Development of Islamic Banking PDFDocumento10 páginasChallenges Facing The Development of Islamic Banking PDFAlexander DeckerAún no hay calificaciones

- The Awareness and Attitude Towards Islamic Banking A Study in MalaysiaDocumento26 páginasThe Awareness and Attitude Towards Islamic Banking A Study in MalaysiaJenny YeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution in Islamic Banking and Finance: Current Trends and Future PerspectivesDocumento25 páginasDispute Resolution in Islamic Banking and Finance: Current Trends and Future PerspectivesSidra MeenaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking in NigeriaDocumento12 páginasIslamic Banking in NigeriaAbdullahi ManirAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Study Islamic Banking and Finance?Documento28 páginasWhy Study Islamic Banking and Finance?Princess IntanAún no hay calificaciones

- Vol 12-2 and 13-1..mabid Al Jarhi..Universal Banking - MabidDocumento65 páginasVol 12-2 and 13-1..mabid Al Jarhi..Universal Banking - MabidObert MarongedzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis On Islamic Banking PDFDocumento5 páginasThesis On Islamic Banking PDFaflnqhceeoirqy100% (2)

- In Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements For: "Islamic Banking"Documento50 páginasIn Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements For: "Islamic Banking"rk1510Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research Papers On Islamic Banking Vs Conventional BankingDocumento7 páginasResearch Papers On Islamic Banking Vs Conventional BankingvguomivndAún no hay calificaciones

- Towards an Islamic Stock MarketDocumento26 páginasTowards an Islamic Stock MarketSyed Ghufran WaseyAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking and Finance MBA (Finance) Abasyn University Peshawar. (Farman Qayyum)Documento35 páginasIslamic Banking and Finance MBA (Finance) Abasyn University Peshawar. (Farman Qayyum)farman_qayyumAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Bank ThesisDocumento8 páginasIslamic Bank ThesisWriteMyStatisticsPaperCanada100% (1)

- D F W P S: Epartment of Inance Orking Aper EriesDocumento49 páginasD F W P S: Epartment of Inance Orking Aper Erieshafis82Aún no hay calificaciones

- Itroduction BankingDocumento8 páginasItroduction BankingusmansulemanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Feasible Acceptance of Al Qard Al-Hassan (Benevolent Loan) Mechanism in TheDocumento13 páginasThe Feasible Acceptance of Al Qard Al-Hassan (Benevolent Loan) Mechanism in TheZulifa ZulAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Thesis Islamic BankingDocumento98 páginasFinal Thesis Islamic BankingEbne Akram100% (2)

- USB ISLAMIC BANKINGDocumento15 páginasUSB ISLAMIC BANKINGtabAún no hay calificaciones

- Parallelism between Interest and Profit Rates ComparedDocumento9 páginasParallelism between Interest and Profit Rates ComparedSayed Sharif HashimiAún no hay calificaciones

- Financial Contracts, Credit Risk and Performance of Islamic BankingDocumento22 páginasFinancial Contracts, Credit Risk and Performance of Islamic BankingUmer KiyaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Importance of Islamic BankingDocumento3 páginasImportance of Islamic BankingHina BibiAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking ExplainedDocumento166 páginasIslamic Banking ExplainedSaadat Ullah KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- AFN20203 - Topic1Documento47 páginasAFN20203 - Topic1soon jasonAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking - The Great Expectations - Docx1Documento3 páginasIslamic Banking - The Great Expectations - Docx1bajaffar2144Aún no hay calificaciones

- DownloadDocumento4 páginasDownloadShaik AmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Project Report Bank Islami CompletedDocumento64 páginasProject Report Bank Islami Completedsameer ahmedAún no hay calificaciones

- F Per 2012 InternationalDocumento5 páginasF Per 2012 InternationalBrandy LeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Finance: An Attractive New Way of Financial IntermediationDocumento24 páginasIslamic Finance: An Attractive New Way of Financial IntermediationHanisa HanzAún no hay calificaciones

- Lecture 2 - An Brief Introduction To Money and Islamic BankingDocumento28 páginasLecture 2 - An Brief Introduction To Money and Islamic BankingborhansetiAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis On Islamic Banking and FinanceDocumento5 páginasThesis On Islamic Banking and Financeafknowudv100% (3)

- Evaluating The Financial Performance of PDFDocumento6 páginasEvaluating The Financial Performance of PDFMehwish ZahoorAún no hay calificaciones

- SSRN Id1712184Documento25 páginasSSRN Id1712184M MustafaAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic BankingDocumento96 páginasIslamic BankingShyna ParkerAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking for SME FinancingDocumento14 páginasIslamic Banking for SME FinancingJoel FernandesAún no hay calificaciones

- Kunhibava 2012Documento11 páginasKunhibava 2012arin ariniAún no hay calificaciones

- Shubuhat On Matter of Bai Al-Inah and TawarruqDocumento17 páginasShubuhat On Matter of Bai Al-Inah and Tawarruqanis suraya mohamed said100% (2)

- PHD Thesis On Islamic Banking PDFDocumento5 páginasPHD Thesis On Islamic Banking PDFcourtneybennettshreveport100% (1)

- Literature Review Islamic Banking SystemDocumento9 páginasLiterature Review Islamic Banking Systemaflsqrbnq100% (1)

- Islamic Banking in PakistanDocumento72 páginasIslamic Banking in PakistanRida ZehraAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Banking Growth in MENADocumento44 páginasIslamic Banking Growth in MENATinotenda DubeAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Finance Acca PaperDocumento6 páginasIslamic Finance Acca PaperAmmar KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- UrlDocumento8 páginasUrlvenztechAún no hay calificaciones

- Condensation in Switchgear and Anti-Condensation HeatersDocumento3 páginasCondensation in Switchgear and Anti-Condensation HeaterswaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Power System Technical ProgramDocumento8 páginasPower System Technical ProgramwaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Substation LayoutDocumento1 páginaSubstation LayoutwaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Control PhilosophyDocumento6 páginasControl PhilosophywaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- 00022445Documento7 páginas00022445waniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Technical Annex: International Protection (IP) Ratings To IEC 529Documento6 páginasTechnical Annex: International Protection (IP) Ratings To IEC 529engrusmanhabibAún no hay calificaciones

- An Extensive Range For All Applications: Evolis SystemDocumento8 páginasAn Extensive Range For All Applications: Evolis SystemRonald H SantosAún no hay calificaciones

- Resistor CalculationDocumento4 páginasResistor CalculationwaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Wind Energy Sarvesh - KumarDocumento26 páginasWind Energy Sarvesh - Kumaranon_228506499Aún no hay calificaciones

- Virtual Retinal Display Technology for Augmented Vision and Medical ApplicationsDocumento6 páginasVirtual Retinal Display Technology for Augmented Vision and Medical Applicationskirthika143Aún no hay calificaciones

- ANSI Device NumbersDocumento7 páginasANSI Device Numbersrajpre1213Aún no hay calificaciones

- Advances in Computer Architecture and AlgorithmsDocumento6 páginasAdvances in Computer Architecture and Algorithmssatya20011Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Etiquettes of Marriage & WeddingDocumento33 páginasThe Etiquettes of Marriage & Weddingpunit_1612Aún no hay calificaciones

- Computer Engineering Sem-1Documento8 páginasComputer Engineering Sem-1waniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Public Policy and Government Affairs:: Orey - EarakDocumento3 páginasPublic Policy and Government Affairs:: Orey - EarakwaniasimAún no hay calificaciones

- Account StatementDocumento3 páginasAccount StatementRonald MyersAún no hay calificaciones

- ASSIGNMENT LAW 2 (TASK 1) (2) BBBDocumento4 páginasASSIGNMENT LAW 2 (TASK 1) (2) BBBChong Kai MingAún no hay calificaciones

- SFM PDFDocumento260 páginasSFM PDFLaxmisha GowdaAún no hay calificaciones

- BUITEMS Entry Test Sample Paper NAT IGSDocumento10 páginasBUITEMS Entry Test Sample Paper NAT IGSShawn Parker100% (1)

- ENT300 - Module10 - ORGANIZATIONAL PLANDocumento34 páginasENT300 - Module10 - ORGANIZATIONAL PLANnaurahimanAún no hay calificaciones

- SPANISH AMERICAN SKIN COMPANY, Libelant-Appellee, v. THE FERNGULF, Her Engines, Boilers, Tackle, Etc., and THE A/S GLITTRE, Respondent-AppellantDocumento5 páginasSPANISH AMERICAN SKIN COMPANY, Libelant-Appellee, v. THE FERNGULF, Her Engines, Boilers, Tackle, Etc., and THE A/S GLITTRE, Respondent-AppellantScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- PFR Volume IDocumento327 páginasPFR Volume IMaria WebbAún no hay calificaciones

- Presentacion Evolucion Excelencia Operacional - Paul Brackett - ABBDocumento40 páginasPresentacion Evolucion Excelencia Operacional - Paul Brackett - ABBHERMAN JR.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Personal Accident Claim FormDocumento5 páginasPersonal Accident Claim FormMadhava Reddy MunagalaAún no hay calificaciones

- General Awareness 2015 For All Upcoming ExamsDocumento59 páginasGeneral Awareness 2015 For All Upcoming ExamsJagannath JagguAún no hay calificaciones

- MAN Machine Material: Bottle Dented Too MuchDocumento8 páginasMAN Machine Material: Bottle Dented Too Muchwaranya suttiwanAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study GuidelinesDocumento4 páginasCase Study GuidelinesKhothi BhosAún no hay calificaciones

- Mail Merge in ExcelDocumento20 páginasMail Merge in ExcelNarayan ChhetryAún no hay calificaciones

- Union BankDocumento7 páginasUnion BankChoice MyAún no hay calificaciones

- AIP WFP 2019 Final Drps RegularDocumento113 páginasAIP WFP 2019 Final Drps RegularJervilhanahtherese Canonigo Alferez-NamitAún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing Domain ...........................Documento79 páginasMarketing Domain ...........................Manish SharmaAún no hay calificaciones

- ENY MRGN 016388 31012024 NSE DERV REM SignDocumento1 páginaENY MRGN 016388 31012024 NSE DERV REM Signycharansai0Aún no hay calificaciones

- 05 - E. Articles 1828 To 1842Documento14 páginas05 - E. Articles 1828 To 1842Noemi MejiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Australian Government Data Centre Strategy Strategy 2010-2025Documento8 páginasAustralian Government Data Centre Strategy Strategy 2010-2025HarumAún no hay calificaciones

- Tally PPT For Counselling1Documento11 páginasTally PPT For Counselling1lekhraj sahuAún no hay calificaciones

- Export Manager or Latin America Sales ManagerDocumento3 páginasExport Manager or Latin America Sales Managerapi-77675289Aún no hay calificaciones

- SEC - Graduate PositionDocumento6 páginasSEC - Graduate PositionGiorgos MeleasAún no hay calificaciones

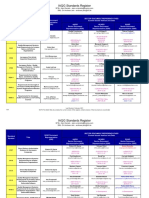

- IAQG Standards Register Tracking Matrix February 01 2021Documento4 páginasIAQG Standards Register Tracking Matrix February 01 2021sudar1477Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nevada Reports 1948 (65 Nev.) PDFDocumento575 páginasNevada Reports 1948 (65 Nev.) PDFthadzigsAún no hay calificaciones

- Dendrite InternationalDocumento9 páginasDendrite InternationalAbhishek VermaAún no hay calificaciones