Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Ed 515882

Cargado por

Dondee Sibulo AlejandroDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Ed 515882

Cargado por

Dondee Sibulo AlejandroCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1

A Critical Review of Adult Learners and Student Government: Recommendations for Practice

Jennifer M. Miles Assistant Professor, Higher Education University of Arkansas 107 Graduate Education Building Fayetteville, AR 72701 (479) 575-5493 jmmiles@uark.edu February 2011

Introduction Colleges and universities provide students with numerous opportunities to become involved on campus. These activities are based on the assertion that involvement will lead to higher levels of satisfaction, higher grade point averages, and increased retention rates. Additionally, opportunities for involvement are believed to assist students with their personal and professional growth and development, including moral and identity development (Evans, 2003). Engagement can occur through curricular and co-curricular means. Students may become engaged through their academic programs, through faculty and student interactions, and through clubs, organizations, and events. One formal structure for student involvement includes student government. Student government associations are in place to represent the needs of students to administrators and faculty (Laosekian-Buggs, 2006). Because student governments exist in order to give students a voice on campus, all students should have access to student government involvement, including opportunities to serve as student government leaders. Contemporary student government associations, however, are often structured to fit the needs, and schedules of, full-time, traditional-aged students. In order to participate as student government officers, students must adhere to specific criteria. In some cases, students must be full-time students, must live within a certain number of miles of campus, may not be permitted to hold outside jobs, and must be available during the summer months to prepare their administrations. Such regulations may prevent adult learners from participating in student government. Adult students have different needs and time constraints than traditional-aged students. If adult students are to receive the benefits of engagement, they must have

opportunities to become engaged. If administrators value the experience and diverse backgrounds that adult students bring to higher education, structures must be examined to ensure that they are appropriate for the needs of all students. Student services staff and administrators need to change their strategies and structures in order to meet the needs of adult learners (Compton, Cox, & Laanan, 2006). It is possible for a student population to change dramatically while the services and activities remain unchanged. That rigidity and incongruence does not serve students well. An unwelcome environment can lead to dissatisfaction, disappointment, and a lack of effort to become involved in the future. In order for student government to serve as an effective mechanism for student engagement, the needs of adult learners and the structure of student government must be examined. Background of the Study Adult Learners Adult learners can be defined as individuals age 25 and older who are engaged in postsecondary learning (Voorhees & Lingenfelter, 2003). Adult learners have specific reasons and goals for attending college, including obtaining skills that will assist them professionally (Compton et al., 2006; Ritt, 2008) and transitioning to a new phase in their lives (Aslanian, 2001). Adult learners, as a group, are more diverse than traditionalaged students. They have different experiences with institutions of higher education, attend college for different reasons, and have different expectations of their college or university (Richardson & King, 1998). For example, unlike their traditional-aged peers, adults often enter institutions of higher education in order to gain new skills and to become more familiar with technology (Compton et al., 2006).

Adults often enter colleges and universities as a result of a major life change, including divorce, loss of a job, or death of a spouse (Compton et al., 2006). Their life experiences can serve as an asset. Adult students can be regarded as more capable of success because of the experiences they bring to their coursework and because of the experiences they have confronting barriers (Richardson & King, 1998). Adult-centered institutions are characterized by offering flexible practices and relating to each adult student as an individual (Mancuso, 2001). Colleges and universities can design programs and services to address the needs of specific student populations, including adult learners (Cook & King, 2005). Some of the flexible services that adult learners may benefit from include extended hours and on-line options (Chickering & Reisser, 1993). Entering college can create additional stress in an adult's life (Compton et al., 2006); they have many demands on their time, including work responsibilities and time spent commuting to campus (Kasworm, 1990; Schlossberg, Lynch, & Chickering, 1989). Additionally, adult learners are not always interested in joining clubs and activities, because they consider their social lives outside the college or university (Compton et al., 2006) and adult students do not have a great deal of time available to spend on campus activities and programs. Student Engagement Student engagement has been found to have positive effects on academic achievement and persistence (Kuh, Kinzie, Schuh, Whitt, & Associates, 2005; Kuh, 2003; Kuh, Cruce, Shoup, Kinzie, and Gonyea, 2008). Engagement includes the time that

students spend in curricular and co-curricular activities, as well as the ways institutions choose to involve the students in such activities (Kuh, 2003). Examples of activities include, but are not limited to, learning communities, orientation, first-year seminars, internships, and mentoring (Forest, 1985; Kuh et al., 2005; Kuh, Kinzie, Buckley, Bridges, & Hayek, 2007; Wang & Grimes, 2001). Engagement in such activities can positively affect academic and social integration, as well as lead to positive overall feelings toward their experience in college (Zhao & Kuh, 2004). In order for services to positively affect student success, the programs must be designed for the students of that institution and the institution as a whole should be dedicated to student success (Kuh et al., 2005). Involvement in campus activities helps students develop relationships with peers, which can positively impact social development and academic success (Astin, 1984; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Rendon, 1994; Tinto; 1993). Research supports the connection between social involvement and academic success for traditional-age college students (Astin, 1993; Kuh et al., 2005; Pace, 1984; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Pascarella, Flowers, & Whitt, 2009; Tinto, 1993). Encouragement to become involved on campus, including student organizations and educationally purposeful activities, can come from staff members (Braxton & McClendon, 2001-2002; Kuh et al., 2005; Kuh et al., 2007). Involvement in activities designed to enhance the educational experience has a positive effect on learning (Astin, 1993; Feldman & Newcomb, 1969; Pace, 1984; Pascarella & Ternezini, 1991). Learning occurs when students can successfully integrate their academic and social activities and experiences (Chickering, 1974; Newell, 1999).

Information gained outside the classroom can be understood by the students on a deeper level and can become more meaningful (Zhao & Kuh, 2004). When students are involved and active in college, that engagement and desire to learn and grow can continue throughout their lives after college (Shulman, 2002). Discussion Barriers to participation in higher education for adults may include personal, professional, and institutional obstacles (Ritt, 2008). Boundaries viewed by adult students can include child care, parking, and access to services. Sometimes, tasks that are easily accomplished by traditional students, such as obtaining a student identification card or meeting with a financial aid representative, can include a great deal of work and inconvenience for an adult student. Adult students have jobs, family responsibilities, and are often times entering the classroom after being away from formal education for several years. Adult students often make tremendous sacrifices to enroll in college. Research is lacking regarding the role of socialization and the success of adult learners (Lundberg, 2003). Because student engagement can positively affect academic performance and the development of critical thinking skills (Carini, Kuh, & Klein, 2006), however, engagement can benefit all students. One way for students to become involved is through their student government association. Typical responsibilities of a student government include distributing student fees, recognizing official student clubs and organizations, coordinating activities, and representing the student body to institutional leaders (Laosebikan-Buggs, 2006). Activities traditionally provided by a student government may or may not be applicable to adult students.

An institution's student government may be operating under the same mindset as 50 or 100 years ago. It may be worthwhile to examine how a student body has changed since the institution was founded and revise the student government structure and constitution, as well as activities the student government is responsible for, to reflect the student demographics and mission of the institution today. If administrators believe that student government is the voice of students, all students should have a voice. Otherwise, student government is the voice of students representing specific sub-populations, a challenge of many student governments (Mackey, 2006; Miller & Nadler, 2006). Adult students may provide a fresh voice to student government. Because of their personal experiences and professional experiences, adult learners may view concerns differently that traditional students who entered college directly from high school. Adult students may interact with administrators, faculty, and fellow students differently. Recommendations Adult learners often have different concerns than how to become involved on campus. For many students, academic success is a priority. Adults are interested in gaining knowledge to help them create successful lives (Shacham & Od-Cohen, 2009). If administrators want adult learners to become involved, they need to determine how to reach these students and how to demonstrate that these types of activities are worth their time. If student government is structured so that it is more accessible for adult students, it may become more accessible to other student populations. The involvement of adult students may also increase the overall interest in student government, increasing numbers of students involved, which may be beneficial to all student governments.

Adult learners may not be aware that student government exists. If they see a poster or receive an email about joining student government, they may dismiss it because they may not think it applies to them. Institutions of higher education need find innovative and creative ways to involve students, making them feel welcome to participate in events and programs (Compton et al., 2006). Students and staff may need to determine ways to interest adult students in student government. For example, adult learners often think of themselves as employees more than they consider themselves students (Compton et al., 2006). If institutions can demonstrate the benefits of student government involvement in terms of building skills of interest to employers, students may be more likely to participate. Traditional students serving in leadership roles may be content with limited involvement of adult learners. It may never occur to traditional-aged students to open the student government to adult learners. In that situation, student government advisors may need to share the concept with the traditional-aged student government leaders. If adult students were to truly be part of the structure, all aspects of student government would need to be examined, such as the times meetings were held, rules regarding part-time students serving on student government, and policies regarding employment. Thought would also need to be spent determining how best to contact adult students and let them know that student government is an option for them. Because adult students have so many demands on their time, they need to be aware of the exact time commitment and the benefits of student government involvement. Adult learners may have very different concerns than those of traditional students. The presence of adult learners may lead to student governments focusing on different causes and working on different goals.

Every student is an individual with different needs and expectations. Adult learners may not be interested in becoming involved in activities such as student governments. Involvement should be a choice. Students should be given options for engagement and be given the opportunity to make their own choices. If a program or activity is supposed to exist, however, for all students, the program should be structured so that all interested students can participate, and experience the benefits of that involvement.

10

References Aslanian, C. (2001). You're never too old. Community College Journal, 71(5), 56-58. Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25, 297-308. Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Braxton, J. M., & McClendon, S. A. (2001-2002). The fostering of social integration and retention through institutional practice. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory, & Practice 3(1), 57-71. Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1-32. Chickering, A. (1974). Commuting versus residential students: Overcoming educational inequities of living off campus. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Chickering, A. W., & Reisser, L. (1993). Education and identity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Compton, J. I., Cox, E., & Laanan, F. S. (2006). Adult learners in transition. In F. S. Laanan (Ed.), New directions for student services, No. 114: Understanding students in transition: Trends and issues, (pp. 73-80). San Francisco: JosseyBass. Cook, B., & King, J. E. (2005). Improving lives through higher education: Campus programs and policies for low-income adults. Washington, DC: Lumina Foundation for Education and American Council on Education Center for Policy Analysis. Evans, J. (2003). Psychosocial, cognitive, and typological perspectives on student development. In Komives, Woodard, and Associates (Eds.), Student services: A handbook for the profession (pp. 179-202). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Feldman, K. A., & Newcomb, T. (1969). The impact of college on students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Forest, A. (1985). Creating conditions for student and institutional success. In L. Noel, R. S. Levitz, D. Saluri, & Associates (Eds.), Increasing student retention: Effective programs and practices for reducing dropout rate. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

11

Kasworm, C. E. (1990). Adult undergraduates in higher education: A review of past research perspectives. Review of Educational Research, 60(3), 345-372. Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we're learning about engagement from NSSE. Change, 35(2), 24-32. Kuh, G. D., Cruce, T. M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. M. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540-563. Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2007). Piecing together the student success puzzle: Research, propositions, and recommendations. ASHE Higher Education Report (Vol. 32, No. 5). San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J. H., Whitt, E. J., & Associates. (2005). Student success in college: Creating conditions that matter. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Laosebikan-Buggs, M. O. (2006). The role of student government: Perceptions and expectations. In Miller and Nadler (Eds.), Student governance and institutional policy: Formation and implementation (pp. 1-8). Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT. Lundberg, C. A. (2003). The influence of time - limitations, faculty, and peer relationships on adult student learning: A causal model. Journal of Higher Education, 74(6), 665-688. Mackey, E. R. (2006). The role of a typical SEC student government. In M. Miller and D. Nadler (Eds.), Student governance and institutional policy: Formation and implementation (pp. 61-68). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Mancuso, S. (2001). Adult-centered practices: Benchmarking study in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 25(3), 165-181. Miller, M. T., & Nadler, D. P. (2006). Student involvement in governance: Rationale, problems, and opportunities. In M. Miller and D. Nadler (Eds.), Student governance and institutional policy: Formation and implementation (pp.9-18). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Newell, W. H. (1999, May/June). The promise of integrative learning. About Campus, 4(2), 17-23. Pace, C. R. (1984). Student effort: A new key to assessing quality (Report No. 11). Los Angeles: University of California, Higher Education Research Institute.

12

Pascarella, E. T., Flowers, L., & Whitt, E. J. (2009). Cognitive effects of Greek affiliation during the first year in college: Additional evidence. NASPA Journal, 46(3), 447-468. Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Rendon, L. I. (1994). Validating culturally diverse students: Toward a new model of learning and student development. Innovative Higher Education, 19(1), 33-51. Richardson, J. T. E., & King, E. (1998). Adult students in higher education: Burden or boon? Journal of Higher Education, 69(1), 65-88. Ritt, E. (2008). Redefining tradition: Adult learners and higher education. Adult Learning, 19(1-2), 12-16. Schlossberg, N. K., Lynch, A. Q., & Chickering, A. W. (1989). Improving higher education environments for adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Shacham, M., & Od-Cohen, Y. (2009). Rethinking PhD learning incorporating communities of practice. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(3), 279-292. Shulman, L. S. (2002). Making differences: A table of learning. Change, 34(6), 36-44. Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Voorhees, R., & Lingenfelter, D. (2003). Adult learners and state policy. Denver, CO: State Higher Education Executive Officers and Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, Chicago, IL. Wang, H., & Grimes, J. W. (2001). A systematic approach to assessing retention programs: Identifying critical points for meaningful interventions and validating outcomes assessment. Journal of College Student Retention, 2(1), 59-68. Zhao, C., & Kuh, G. D. (2004). Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 115-138.

También podría gustarte

- Inclusion PortfolioDocumento20 páginasInclusion Portfolioapi-291611974Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Sample of Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA StyleDocumento10 páginasA Sample of Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA StyleRobert Holguin Goray100% (2)

- Theory of Academic PerformanceDocumento10 páginasTheory of Academic PerformanceRain Malabanan0% (1)

- Consolidated Grade Sheet For Adviser OnlyDocumento4 páginasConsolidated Grade Sheet For Adviser OnlyHoney Crystel Padoc100% (3)

- The State of Mentoring - Change Agents ReportDocumento31 páginasThe State of Mentoring - Change Agents ReportIsaac FullartonAún no hay calificaciones

- Theory To Practice PaperDocumento9 páginasTheory To Practice Paperapi-457523357Aún no hay calificaciones

- Upcat Reviewer Practice Test 1Documento27 páginasUpcat Reviewer Practice Test 1Michelle Panganduyon100% (1)

- Rankine Cycle Alejandro Cabico MadjilonDocumento109 páginasRankine Cycle Alejandro Cabico MadjilonDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Rankine Cycle Alejandro Cabico MadjilonDocumento109 páginasRankine Cycle Alejandro Cabico MadjilonDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Student EngagementDocumento16 páginasStudent EngagementP. HarrisonAún no hay calificaciones

- Non-Academic Student Supports Improve OutcomesDocumento4 páginasNon-Academic Student Supports Improve OutcomesanoriginalusernameAún no hay calificaciones

- School Environment Factors Impact Student AchievementDocumento15 páginasSchool Environment Factors Impact Student Achievementcharls xyrhen BalangaAún no hay calificaciones

- Review of Related LitDocumento5 páginasReview of Related LitJapeth MattaAún no hay calificaciones

- Term PaperDocumento15 páginasTerm PaperJederiane BuizonAún no hay calificaciones

- What Student Affairs Professionals Need To Know About Student EngagementDocumento25 páginasWhat Student Affairs Professionals Need To Know About Student EngagementMichael GalvinAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: SERVICE LEARNING 1Documento12 páginasRunning Head: SERVICE LEARNING 1api-391376560Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research PaperDocumento11 páginasResearch PaperMichael AgustinAún no hay calificaciones

- Student Leadership Impact on Academic EngagementDocumento28 páginasStudent Leadership Impact on Academic EngagementAntonette ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- A S Artifact 2 Final Research PaperDocumento13 páginasA S Artifact 2 Final Research Paperapi-663147517Aún no hay calificaciones

- Literature ReviewDocumento12 páginasLiterature Reviewapi-449287215Aún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of Student Engagement On Academic Performance and Quality of Relationships of Traditional and Nontraditional StudentsDocumento22 páginasImpact of Student Engagement On Academic Performance and Quality of Relationships of Traditional and Nontraditional StudentsGeorge GomezAún no hay calificaciones

- Hesa Writing SampleDocumento9 páginasHesa Writing Sampleapi-397238352Aún no hay calificaciones

- Measuring College Student Satisfaction: A Multi-Year Study of The Factors Leading To PersistenceDocumento19 páginasMeasuring College Student Satisfaction: A Multi-Year Study of The Factors Leading To PersistencegerrylthereseAún no hay calificaciones

- Full Thesis RevisionDocumento19 páginasFull Thesis RevisionChristian Marc Colobong PalmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Factors Affecting Students' Participation in Co-curricular ActivitiesDocumento4 páginasFactors Affecting Students' Participation in Co-curricular ActivitiesRoselyn Dela VegaAún no hay calificaciones

- Acc Scholarly ReflectionDocumento5 páginasAcc Scholarly Reflectionapi-437976054Aún no hay calificaciones

- JPSP - 2022 - 722Documento7 páginasJPSP - 2022 - 722SakiAún no hay calificaciones

- Student Development and Life Skills AssignmentDocumento7 páginasStudent Development and Life Skills AssignmentTakudzwa JijiAún no hay calificaciones

- Socioemotional BehaviorDocumento4 páginasSocioemotional BehaviorArlene L PalasicoAún no hay calificaciones

- Enhance Curriculum 12Documento13 páginasEnhance Curriculum 12denmark dayaoAún no hay calificaciones

- A Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationDe EverandA Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationAún no hay calificaciones

- Service-Learning Benefits Students with Behavioral ProblemsDocumento17 páginasService-Learning Benefits Students with Behavioral ProblemsBo Na YoonAún no hay calificaciones

- Graded Future Trends ExerciseDocumento11 páginasGraded Future Trends Exerciseapi-464438746Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hoogkamer Transfer CenterDocumento14 páginasHoogkamer Transfer Centerapi-208659722Aún no hay calificaciones

- Exploring The Association Between Campus-1Documento22 páginasExploring The Association Between Campus-1Jane MacalosAún no hay calificaciones

- Buchalski Budhram Carlson Waran Quantitative Assessment Proposal Fall 2011Documento27 páginasBuchalski Budhram Carlson Waran Quantitative Assessment Proposal Fall 2011ruganesh10Aún no hay calificaciones

- Student Satisfaction and Persistence: Factors Vital To Student RetentionDocumento18 páginasStudent Satisfaction and Persistence: Factors Vital To Student RetentionAsti HaryaniAún no hay calificaciones

- SDLS101R221591U-ASS2 DoxDocumento5 páginasSDLS101R221591U-ASS2 DoxJahseh MezaAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Learning Spaces and Student EngagementDocumento17 páginasSocial Learning Spaces and Student EngagementAbi RamanathanAún no hay calificaciones

- Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., and Felten, P. (2011) Students As Co-CreatorsDocumento13 páginasBovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., and Felten, P. (2011) Students As Co-CreatorsAnnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Impacts of the movement of sps and sls facilities from Gk to Bosso Campus on Student Well-BeingDocumento34 páginasImpacts of the movement of sps and sls facilities from Gk to Bosso Campus on Student Well-BeingMicheal kingAún no hay calificaciones

- Pre University Prepared Students A Programme For Facilitating The Transition From Secondary To Tertiary EducationDocumento15 páginasPre University Prepared Students A Programme For Facilitating The Transition From Secondary To Tertiary Educationangle angleAún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of extracurricular activities on student academic performanceDocumento3 páginasImpact of extracurricular activities on student academic performanceKimberly MarajasAún no hay calificaciones

- Group 3 Chapter 1 To 3Documento19 páginasGroup 3 Chapter 1 To 3Rowellie Arca100% (1)

- Review of Related Literature LocalDocumento6 páginasReview of Related Literature LocalNoelli Mae BacolAún no hay calificaciones

- 9 Extracurricular Activity Involvement On The Compassion Academic Competence and Commitment of Collegiate Level Students A Structural Equation ModelDocumento14 páginas9 Extracurricular Activity Involvement On The Compassion Academic Competence and Commitment of Collegiate Level Students A Structural Equation Modelanthony gadiAún no hay calificaciones

- Leadership and GovernanceDocumento23 páginasLeadership and GovernanceJeffrey T EngAún no hay calificaciones

- Educational Interface PostprintDocumento18 páginasEducational Interface PostprintLetsie SebelemetjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Foundational Assumptions For Successful Transition: Examining Alternatively Certified Special Educator PerceptionsDocumento20 páginasFoundational Assumptions For Successful Transition: Examining Alternatively Certified Special Educator PerceptionsGeorgia GiampAún no hay calificaciones

- A Qualitative Study of Students With Behavioral PRDocumento3 páginasA Qualitative Study of Students With Behavioral PRRefenej TioAún no hay calificaciones

- R227715P SDLS Ass2Documento5 páginasR227715P SDLS Ass2HarrisAún no hay calificaciones

- Sarahknight, Cocreation of The Curriculum Lubicz-Nawrocka 13 October 2017Documento14 páginasSarahknight, Cocreation of The Curriculum Lubicz-Nawrocka 13 October 2017陳水恩Aún no hay calificaciones

- Manuscript RevisedDocumento48 páginasManuscript RevisedVincent James MallariAún no hay calificaciones

- Do Less-Inclined Students Learn from Mandatory Service LearningDocumento6 páginasDo Less-Inclined Students Learn from Mandatory Service LearningBerfu Almina KaragölAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To ImpactDocumento2 páginasIntroduction To Impactjaysah viloanAún no hay calificaciones

- Promoting Student Engagement in The ClassroomDocumento20 páginasPromoting Student Engagement in The ClassroomyassineAún no hay calificaciones

- An Exploration of Factors Influencing College Students' Academic and Social AdjustmentDocumento10 páginasAn Exploration of Factors Influencing College Students' Academic and Social Adjustmentanusha shankarAún no hay calificaciones

- Annotated-Mikaila Esuke Engl101 Position Paper-1Documento12 páginasAnnotated-Mikaila Esuke Engl101 Position Paper-1api-622339925Aún no hay calificaciones

- Study HabitsDocumento22 páginasStudy HabitsNamoAmitofou100% (1)

- ACT Working Learners Lit ReviewDocumento27 páginasACT Working Learners Lit Reviewdraine 21Aún no hay calificaciones

- CHAPTER IDocumento2 páginasCHAPTER ILaurenz Miguel MercadoAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Research Says On Inclusive EducationDocumento4 páginasWhat The Research Says On Inclusive EducationNasrun Abd ManafAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding The Student Experience in High School: Differences by School Value-Added RankingsDocumento30 páginasUnderstanding The Student Experience in High School: Differences by School Value-Added RankingsRichelle LlobreraAún no hay calificaciones

- ED598647Documento27 páginasED598647Christian CardiñoAún no hay calificaciones

- Asnwers-1 2 PDFDocumento1 páginaAsnwers-1 2 PDFDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Tri Go No Me Tri ADocumento396 páginasTri Go No Me Tri Aslanas_1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rosmaina 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 391 012064Documento10 páginasRosmaina 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 391 012064Dondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Physico-chemical Characteristics of the Queen Pineapple CultivarDocumento2 páginasPhysico-chemical Characteristics of the Queen Pineapple CultivarDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Exam Style Questions: GuidanceDocumento12 páginasExam Style Questions: GuidanceLynseyAún no hay calificaciones

- Trading 101 BasicsDocumento3 páginasTrading 101 BasicsNaveen KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- This Study Resource Was: Math 17 Finals - 1Documento2 páginasThis Study Resource Was: Math 17 Finals - 1Dondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Unit 2 Definition of The Derivative PDFDocumento15 páginasUnit 2 Definition of The Derivative PDFDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Exam Reviewer: Math 17Documento2 páginasFinal Exam Reviewer: Math 17Dondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Hand BookDocumento79 páginasHand BookumeshnihalaniAún no hay calificaciones

- IFCMarketsBook PDFDocumento12 páginasIFCMarketsBook PDFDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Name: Teacher: Date: Score:: Multiplying With Powers of TenDocumento1 páginaName: Teacher: Date: Score:: Multiplying With Powers of TenDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Adding and Subtracting Radical ExpressionsDocumento2 páginasAdding and Subtracting Radical ExpressionsJera ObsinaAún no hay calificaciones

- ISE DevelopingFXTradingStrategy 021108 PDFDocumento63 páginasISE DevelopingFXTradingStrategy 021108 PDFDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Graphing Trig Functions PDFDocumento4 páginasGraphing Trig Functions PDFMark Abion ValladolidAún no hay calificaciones

- Graphing Trig Functions PDFDocumento4 páginasGraphing Trig Functions PDFMark Abion ValladolidAún no hay calificaciones

- Order of OperationsDocumento2 páginasOrder of OperationsDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- LE1 Sample Exam 2 PDFDocumento1 páginaLE1 Sample Exam 2 PDFHanalit ZafraAún no hay calificaciones

- Order of OperationsDocumento2 páginasOrder of OperationsDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Equation of A Line WorksheetDocumento11 páginasEquation of A Line WorksheetAra HerreraAún no hay calificaciones

- Elements, CMPDS, Mix Ws PDFDocumento4 páginasElements, CMPDS, Mix Ws PDFDean JezerAún no hay calificaciones

- Ooo Mdas Integers Foursteps Positive 001Documento2 páginasOoo Mdas Integers Foursteps Positive 001api-314809600Aún no hay calificaciones

- Alejandro - Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC)Documento45 páginasAlejandro - Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC)Dondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- A1-1 Otec 2Documento109 páginasA1-1 Otec 2Dondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Electric Charge and Electric FieldDocumento5 páginasElectric Charge and Electric FieldDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- 09 Master BuilderDocumento6 páginas09 Master BuilderDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Automotive Brake Disc and CalliperDocumento32 páginasAutomotive Brake Disc and CalliperDondee Sibulo AlejandroAún no hay calificaciones

- Eccd Checklist SummaryDocumento6 páginasEccd Checklist SummaryAlex CalannoAún no hay calificaciones

- A Level CreditDocumento42 páginasA Level CreditNepalese AssociationAún no hay calificaciones

- Bright Futures 2012Documento2 páginasBright Futures 2012GraceKolczynskiAún no hay calificaciones

- Calendar Semester I and II 2020 2021Documento3 páginasCalendar Semester I and II 2020 2021Ronnie AtuhaireAún no hay calificaciones

- Carnegie Mellon 2006-2007 Academic CalendarDocumento5 páginasCarnegie Mellon 2006-2007 Academic CalendarMegeve LiuAún no hay calificaciones

- Admission And: Tertiary Enrollment ProcedureDocumento1 páginaAdmission And: Tertiary Enrollment Procedureangel relobaAún no hay calificaciones

- Form 18 SampleDocumento11 páginasForm 18 SampleNhil Cabillon QuietaAún no hay calificaciones

- Illinois Institute of Technology - Chicago (Chicago, Illinois)Documento5 páginasIllinois Institute of Technology - Chicago (Chicago, Illinois)roopam_wonderAún no hay calificaciones

- 2018 Forces IgcseDocumento10 páginas2018 Forces IgcseFatima AhmadAún no hay calificaciones

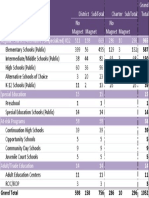

- EdEx - Dist of School Types by Magnet and District StatusDocumento1 páginaEdEx - Dist of School Types by Magnet and District StatusDamien NewtonAún no hay calificaciones

- Greater Albany Public Schools CalendarDocumento1 páginaGreater Albany Public Schools CalendarSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneAún no hay calificaciones

- COVID-19 Cases in Florida SchoolsDocumento102 páginasCOVID-19 Cases in Florida SchoolsDavid SeligAún no hay calificaciones

- List of Board GRW SchoolsDocumento49 páginasList of Board GRW Schoolstariq_hussain_2063% (8)

- Sanchez Mira Institute Lifelong Education Course ScheduleDocumento8 páginasSanchez Mira Institute Lifelong Education Course ScheduleOcterley Love BlancoAún no hay calificaciones

- General Certificate of Education: Information SheetDocumento2 páginasGeneral Certificate of Education: Information SheetStefan ReyAún no hay calificaciones

- 0620 w19 Ms 21 PDFDocumento3 páginas0620 w19 Ms 21 PDFVikas TanwarAún no hay calificaciones

- Phil - IRI Enrolment Pre-Test (Filipino) Frustration % Instructional M F T M F T M F Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 TotalDocumento32 páginasPhil - IRI Enrolment Pre-Test (Filipino) Frustration % Instructional M F T M F T M F Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 TotalJulia Geonzon LabajoAún no hay calificaciones

- UAE - Schools - الجاليه المصريه بدبيDocumento33 páginasUAE - Schools - الجاليه المصريه بدبيwalidAún no hay calificaciones

- The GCP Reunion: Groningen Children's ProjectDocumento15 páginasThe GCP Reunion: Groningen Children's ProjectRomulo CasisAún no hay calificaciones

- 03082018-M.a. Applied Psychology - First Admssion ListDocumento4 páginas03082018-M.a. Applied Psychology - First Admssion ListShabana AqilAún no hay calificaciones

- Schools in Uttar Pradesh: Ryan International SchoolDocumento12 páginasSchools in Uttar Pradesh: Ryan International SchoolRavi Prakash RaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Lahore Qualification Top Performers November 2013Documento2 páginasLahore Qualification Top Performers November 2013tariqbashirAún no hay calificaciones

- Study Abroad at Drexel University, Admission Requirements, Courses, FeesDocumento8 páginasStudy Abroad at Drexel University, Admission Requirements, Courses, FeesMy College SherpaAún no hay calificaciones

- COBSE Member Boards and Councils ListDocumento2 páginasCOBSE Member Boards and Councils ListYogesh ChhaprooAún no hay calificaciones

- Summary - District EnrolmentDocumento91 páginasSummary - District Enrolmentapi-273918959Aún no hay calificaciones

- FAFSA The How-To Guide For High School StudentsDocumento24 páginasFAFSA The How-To Guide For High School StudentsKevinAún no hay calificaciones

- ResumeDocumento2 páginasResumeapi-491286887Aún no hay calificaciones

- Catholic School Alum Requests Refund Due to Missing Name in YearbookDocumento1 páginaCatholic School Alum Requests Refund Due to Missing Name in YearbookScytllaAún no hay calificaciones