Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Anthropology: Desiring The Other

Cargado por

Mary Jane de GuzmanTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Anthropology: Desiring The Other

Cargado por

Mary Jane de GuzmanCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1 DRAFT ONLY Desiring the Other: Cross-Border Sexuality and the Filipino Male By Soledad Natalia M.

Dalisay, Michael L. Tan and Raul Ting

spatial displacement may be an integral part of the production of desire Jokinen and Veijola, 1997

INTRODUCTION: Global trends in the last century have increased the international mobility of human populations. Travel has become much more frequent because of work, studies or leisure. It is against this backdrop that cross-border relations have become a vital issue of research. One important aspect of cross-border relations is sexuality. The intimate connection between travel and sexual desire has long been recognized (Mackie, 2000). Travel advertising has banked on aspects of sexuality as a come-on for clients. For instance, who will not recall the much quoted Singapore girl Youre a great way to fly which is said to have launched a million flights for Singapore Airlines. It is this travel = sexuality connection that this study will address. In the Philippines, travel outside the country is done for several reasons, among which, are: (1) those that are work-related - this would include short-term business meetings, conferences, seminars, trainings and workshops that last for a few days to a week or so, as well as long-term contract work that would take months or years before a worker goes home; (2) for studies this would also entail a few months for short courses to a few years for degree courses; (3) holiday and tours wherein the trip is purely for leisure and may be considerably shorter in duration compared with the first two cases. This study will cover Filipino men who travel for all three aforementioned purposes. For many travelers, there is the expectation of sexual encounters while abroad. These encounters could either be casual, commercial, or transactional. In some instances, relations with deep romantic feelings are forged. It is also important to point out that it is

2 not uncommon for one to encounter business travelers or students who have extended their stay abroad to allow for a non-work related respite. It is recognized that across country borders, there is a reconfiguration not only of spatial relations between and among individuals, but of social relations as well (Pries, 2001). This is true for sexual relations. The other seems more desirable, sexual norms and values are more relaxed, the foreign land becomes a site for pleasure (Lyttleton and Amarapibal, 2002), and may I say, for illicit pleasures. Mackie (2000) noted that tourist destinations in Southeast Asia have been referred to as illicit spaces. This is very much similar to the Western construct of the Orient as exotic and esoteric, hence, more desirable. From the Western travelers gaze, the Orient is a remote space, hence, it is perceived to be what Gupta and Ferguson (2002) called as the most other of others, therefore, more sexually desirable. Thus, the setting and the social relations in the new setting, including meanings put into these social relations, have become vital points in the study of cross-border sexuality. Moreover, exposure to norms very much different from what one complies with in the homeland appears to be a vital factor in how one reshapes his or her sexuality abroad. Crossing cultural boundaries has been viewed to potentially alter sexual behavior (Herdt, 1997) and sexual identity is negotiated (Santos and Mune in Darwin, Wattie and Yuarsi (eds.), 2003). Sexual relations that are casual in nature may end up as short-term one night stands or flings. This is the context in which most commercial sexual encounters occur. For instance, among Filipino seafarers, the AB or akyat barko (going up the ship) is still being practiced, though, is reportedly controlled nowadays because of the 9/11 incident which triggered the enforcement of more stringent anti-terrorist measures on shipping vessels. This entails women who go up the ship when it is docked on the shore to provide the seafarers with sexual services for a fee. Seafarers are also notorious for having a girl in every port. And in some cases lead to building second families abroad and minor wives. In some cases, brief sexual encounters result to the couple developing deep romantic feelings that last for longer periods of time and entail repeated visits. For Filipino OFWs (Overseas Filipino Workers) on job contract, it is not unusual for them to take on girlfriends or even obtain other wives and form second families among those who are already married and with families waiting for them at home. Maintaining a monogamous relationship appears to be a struggle for some of the OFWs. Quite interestingly, also, although sexual relations with local foreign nationals are established, many of the OFWs seem to end up with fellow OFWs. Thus, it would be important to note when and why foreign partners are desired and in what contexts are Filipino partners still preferred even outside of their home country. Another aspect of cross-border sexuality pertains to same sex relations. Go go bars in the Pat Pong area in Bangkok are favorite cruising sites abroad for Filipino men, gays and heterosexuals alike. Pink tourism has become quite popular in areas in Bangkok and in Boracay, the Philippines. Potato Queens and Rice Queens are terms used to refer to gays and their sexual preferences with direct reference to ethnicity.

Still another important aspect of cross-border sexuality is the cyberspace. In cyberspace one need not spend for a travel ticket. Given just the hardware and probably a webcam plus a good Internet connection (there are internet cafes in even hole-in the wall stalls in many of the urban areas in the Philippines), one could easily navigate through the net and join fora and chat rooms, which are sites for cyber sex. Furthermore, one could easily visit these sites and schedule an SEB (sex eye ball cyber language for meeting in person to have sex) with potential partners from anywhere in the world. Thus, given the above considerations, understanding cross-border sexuality gains importance especially because of its implications on sexual and reproductive health. This study aims to contribute to the quest for a better understanding of cross-border sexuality.

PROBLEM STATEMENT:

This study addressed the following questions: 1. What are the travel patterns within the Southeast Asian region involving Filipino men? What is the composition of these flows of Filipino men? 2. In what contexts do Filipino men engage in sexual relations with foreigners or with fellow Filipinos abroad? 3. What are the dynamics in cross-border sexual relations and how do structural factors shape or direct these relationships? How does the imagined other contribute to meaning construction in sexuality among Filipino men who engage in cross-border sexual relations?

OBJECTIVES: This study sought to achieve the following objectives: 1. To map out destinations of Filipino men as they travel within the Southeast Asian region and China as well as the country of origin of foreign male travelers coming into the Philippines; 2. To identify the composition of these flows of men to other countries within the region;

4 3. To find out how and why they engage in sexual relations with either foreigners or fellow Filipinos while abroad and through the Internet; and, 4. To explore the vulnerabilities and dynamics of Filipino male cross-border sexualities as situated within its socio-cultural, political and economic contexts.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK:

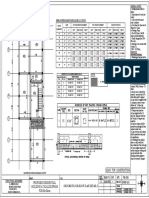

Largely unequal power relations between an individual and the imagined other as well as by imbalance of power between one country and another shape cross-border sexuality. Authors have recognized the relationship between power, sexuality and sexual spaces. For instance, Gupta and Ferguson (2002) wrote about the hierarchical interconnection of spaces. There is also the article by Jolly and Manderson (1997) that discussed about the political economy of sex. Because of the salience of political economy in understanding space, mobility and sexuality, this will be used as the theoretical frame that will guide data collection and analysis of this study. Figure 2 below shows the analytical framework that has been developed for this study. The figure shows that within sexual spaces, sexuality is defined by ones identity. Identity will be viewed in this study as how one configures oneself in terms of class, ethnicity and gender. The paragraphs below define more clearly how the concepts of class, ethnicity and gender will be dealt with in this study. Class referred to income class with variations in income delineating the desiring subject as well as the object of desire. Normally, it is the traveler who possess greater economic power, thus, he occupies a more privileged position compared with his disadvantaged partner abroad.

Class

History

Ethnicity

Identity

Desire

CrossBorder Sexuality >Travel >Internet

Gender

Technology, Mass Media

Socio-Cultural/Economic/Political Context (Power Inequalities)

Fig. 2. Framework for the Study on Cross-Border Sexuality

6 Ethnicity and race included reference to ones ethno-linguistic and racial affiliations and how these figured in defining sexuality of the men within the context of travel as the men cross country borders. Cross border sexuality is constructed based on how one has fantasized about the exotic other, how representations of ones own culture and that of the other affect what was perceived to be desirable and what was not. Ethnic bias and racism are vital aspects herein. Gender is deemed to be an important factor, particularly when viewed within the framework of gender power relations between the traveler and his partner. This study looked into how transactions and negotiations were carried out for entitlements within the relationship. This study focused on the male travelers gaze, both heterosexual and the men who have sex with men or msm. Class, ethnicity, and gender are factors that contribute to the shaping of the identity of an individual. History would include both the history of the nation and the personal history of the traveler as these have influenced erotic desire. Technology and mass media, particularly, how these have shaped erotic desires of the men and which ultimately became a factor that contributed to the development of cross border sexuality as the men navigated through geographical space or in cyberspace. Travel entails encountering experiences that are different from those encountered in ones daily life in the homeland. Sex in another place is not an experience of everyday occurrence. This somehow, has contributed to its desirability. Though sex was not necessarily the primary purpose of the travel, sex became part of the itinerary for some travelers. Many reasons could have pushed an individual to seek for sex. A review of the literature on migration points to unmet emotional or psychological needs or economic power among others (Santos and Mune in Darwin, Wattie and Yuarsi (eds.), 2003). This study covered two types of travelers, namely, those traveling because of work or for further studies. Also, this study looked into the type of relationship travelers engage in while abroad in terms of duration both short-term and long-term, in terms of emotional ties forged whether there is deep emotional bond or lack of it, and, on the type of partner sought whether with a foreigner or with a fellow Filipino. Aside from travel across country borders, this study covered aspects of crossborder sexuality in cyberspace. Chat rooms, various on-line fora and websites offering dating services will be visited. It was not uncommon for virtual partners to agree to meet personally for an eyeball and actually travel for this purpose. The actual experience of searching for sex, whether deliberately or consequentially, while traveling contributed further to a reconfiguration of ones identity and sexuality.

7 All of these occur within a given space. Space, in the study, will refer not only to geographical space but to social and virtual spaces as well. Finally, all these are embedded within the wider socio-cultural, economic and political contexts and operate under unequal power relations within these various contexts.

METHODOLOGY: Data Gathering: This is a qualitative study that entailed the use of several research methods.

1) Review of Relevant Literature This was the primary data collection method used and included reports from government and non-government organizations, news reports, magazines and journals, books and publications on the world wide web were searched.. This was supplemented by other qualitative data gathering methods. (2) Focus Group Discussion this was done with 9 self-identifying heterosexual seafarers aged from 30 to 67. All except 3 are still in active service. The three have retired recently. The FGD participants have been seafarers for a range of 7 to 32 years. (3) In-Depth Interviews This was done with 3 men having sex with men with ages 30, 35 and 47. All were professionals and stated that their foreign travels were mostly connected with their work, as in attendance in conferences or for graduate studies. Informants were given the code names N30S, T35P and E47P. Both N30S and T35P did graduate studies in Bangkok, Thailand. (4) Virtual Ethnography On-line interviews were done with 5 men having sex with men. The study focused on gay chat rooms since this was more convenient for the co-author to access, being chatter himself. It requires an adaptive methodology since the participants and subcultures under study are often transient in nature, anonymous and may even be experimental (Porter, 1997) with participants joining in and leaving the setting when they log in-log out and may opt to remain offline. At the time of the study, the Filipino chatters normally account for an estimated 80% of chatters at any given time and are the second largest listed nationality as featured in the surveys. This study used the general category of men having sex with men because the informants taken were really a heterogeneous mix that included both self-identifying gays as well as one informant who simply wanted to be identified as MSM. Individual interview was deemed as the most effective data gathering method for the MSM group because this is not a homogeneous group that would lend well to an FGD. In the

8 individual interview each informant was able to narrate his own views and experiences freely. For the cyberspace part of the study, those who became informants were informally interviewed through another chat application, particularly the yahoo messenger, where transcripts were saved for references with their consent. Other methods employed were phone-talk and when feasible, meeting the chatter in person.

DATA ANALYSIS:

Data were analyzed with the end-in-view of developing a deeper understanding of cross-border sexuality within the Southeast Asian context. To analyze the data gathered, concepts of social construction and symbolic interaction were employed with political economy as the overarching framework.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS: Consent of all interviewees and FGD participants was secured. Particularly for the cybersex part, those who declined to be interviewed were not pursued. Consent of chatters was secured to include portions of their posted messages in this report. Substituting their real names with codes in the write-up ensured their anonymity. No photographs were taken and interviews were taped only with the consent of the interviewees. Tapings were stopped when the interviewee requested so. Presentation of initial findings to all informants will be done prior to final report writing. Moreover, in appreciation for their participation in the study, tokens were given to all informants.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY: This study focused on cross-border sexuality from one side of the regional mobility flow, specifically the perspective of the Filipino male, both heterosexual and msm. While statistical data showed the flow of men from outside coming into the country or foreigners coming to the Philippines as well as Filipinos moving out or traveling out of the country, qualitative data more specifically addressed one side of the flow, that is, the movement of Filipinos outside the country. Because the methodology emphasized the use of secondary data as the primary data collection method, focus was placed on seafarers and the msm, on which a sufficient number of studies were done in the past that enabled further analysis. The scope of the study was limited to China and Southeast Asia, which included Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Lao PDR, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Cambodia and the Philippines. It is important to state that this study should be considered as preliminary and does not claim application of its findings to the wider Filipino population.

FLOW OF MEN Foreign Visitors to the Philippines Mobility of individuals from and to the Philippines has been steadily on the rise (Bugna and Ybanez, 2000, DOT Statistics, 2000-2004; NSO, 2001). Developments in transportation and communication technology have greatly facilitated world travel for work or for leisure. Statistics from the Department of Tourism have shown that from 2003 to 2005, visitor arrivals have increased with majority coming from countries within the Asian continent. The highest visitor arrivals were logged in 2004. The table below shows the number of visitors the Philippines has had in 2003, 2004 and 2005.

Table 1. Visitor Arrivals by Continent of Origin* Foreign Visitor 2003 Arrivals Asia 1,082,430 America 444,264 Europe 176,618 Oceania 106,109 Africa 1,442 Others (unspecified) 17,039 Total 1,907,226 *Source: Department Of Tourism 2004 1,274,150 545,867 210,215 132,186 2,390 22,802 2,291.352 2005 1,077,747 445,079 174,932 100,157 1,580 19,124 1,907,405

Table 2 shows the trend for foreign visitors coming in by air for the years 2000, 2002 and 2004 from the ASEAN region and China. The data shows that males were more mobile than the females as the findings show that majority of the visitors were males. The data also reveals that there was a slight decrease in the number of visitors from 2000 to 2002 for some of the countries within the ASEAN region and China. Table 3 shows the destination of foreign visitors from ASEAN member countries and the regions of destination in the Philippines for the period January to September 2006. Apparently, the most visited regions were Regions VII and III. Singaporeans,

10 Table 2. Air Visitor Arrivals by Country of Residence and Sex

COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE

YEAR & SEX

2000 2002 2004 Male Female Not Stated Male Female Not Stated Male Female Not Stated 1,263 539 19 1,473 647 16 1,481 586 17 229 87 5 807 233 14 851 316 18 8,968 4,039 176 8,581 3,713 219 10,505 4,872 299 142 55 2 352 120 3 340 107 4 30,176 10,352 439 23,568 7,358 361 23,958 8,438 306 797 282 29 604 240 23 637 266 20 39,423 10,560 202 46,458 10,628 257 47,133 12,579 266 9,521 5,710 202 12,476 5,822 192 14,356 6,804 199 1,273 835 114 2,331 1,347 144 3,067 1,615 139 6,757 3,337 486 14,707 7,915 625 19,652 11,449 1,745

Brunei Cambodia Indonesia Laos Malaysia Myanmar Singapore Thailand Vietnam China

Source: Department of Tourism

Table 3. Distribution of Regional Travelers in the Philippines January to September 2006

Region of Destination in the Philippines Brunei Cambodia Indonesia Laos Malaysia Myanmar Singapore Thailand Vietnam Total

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII CAR Total

18 0 0 5 0 99 61 0 111 47 177 167 2 48 735

0 0 0 3 0 16 16 0 0 11 0 21 1 97 165

8 19 750 145 180 186 1,129 23 172 175 877 299 80 359 4,402

0 0 0 12 0 11 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 0 31

45 11 2,938 153 156 385 2,150 59 805 244 941 285 29 529 8,730

0 0 0 13 0 12 18 0 0 14 0 0 12 0 69

105 35 1,601 436 320 1,242 3,529 97 101 276 1,106 166 54 853 9,921

164 43 871 203 242 409 1,275 59 118 206 728 85 36 470 4,909

8 0 0 4 0 124 67 0 261 57 27 19 2 216 785

348 108 6,160 974 898 2,484 8,245 238 1,568 1,038 3,856 1,042 216 2,572 29,747

Source: Department of Tourism

11 closely followed by Malaysians, topped the list of foreign visitors to the country. The country had the least number of visitors from Myanmar, the only country within the region where a visa had to be secured for travel to the Philippines. It is probable that securing a visa was a deterrent for Myanmar residents to travel to the Philippines.

Movement of Filipinos Overseas Table 4 below shows the reasons for outbound travel of Philippine residents for December 2005. The table shows that the most common reason given for travel by Philippine nationals in the merry month of December in the year 2005 was to go on a holiday. Another common reason given was to visit friends and relatives. The preferred destination within the ASEAN region and China for holiday travel was Hong Kong with Singapore a far second. Travel rates to Hong Kong are very affordable and this probably, contributed immensely to its popularity. Hong Kong also seems to be the preferred destination for employment overseas.

Table 4. Outbound Philippine Residents by Port of Disembarkation and Purpose of Travel - December 2005

Port of Disembarkation

Holiday

Business

Official

Employment

Convention

Visit Relatives Friends

Incentive

Others

Not Stated

Bangkok Beijing Hong Kong Kota Kinabalu Kuala Lumpur Singapore Others Total

3,476 521 20,044 316 1,410

770 62 2,242 24 417

9 16 50 5 54 134

765 7 3,454 82 127 1,087 1,856 7,378

282 28 561 1 170 390 175 1,607

1,217 36 5,918 247 814 4,551 3,295 16,078

1 4 1 5 2 13

847 42 4,648 160 529

2,047 103 13,522 221 695

7,560 1,840 4,185 989 37,512 6,344

2,472 4,477 2,240 5,945 10,938 27,010

Source: Department of Tourism

Generally, though, greater mobility of Filipinos, particularly those going out of the country, has been attributed to overseas contract employment. Notably, more and more of the Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) are going to countries in Asia (Kanlungan, 2000, Bugna and Ybanez, 2000) because of the recent economic boom in the region. Also of interest is the growing trend of feminization of the export labor force of the country with the women outnumbering the men, especially in Asia (Santos, 2002). In the report prepared by Laura Engle (2004) for the International Organization for

12 Migration, Filipino female overseas workers comprise 70% of the total number of OFWs. Opportunities for travel seem to be linked to the general economic conditions in a country with the more economically privileged countries like Singapore and Malaysia outnumbering by a large proportion travelers from the less economically privileged countries like Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar. The Kanlungan Center Foundation Inc. (2000) reported that as of 1999, total number of OFWs all over the world numbered 2.98 M with almost 90% of land-based workers leaving for Asia (45.88%) and the Middle East (43.71%). For the year 2000, the top ten country destinations for land-based OFWs were Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, UAE, Italy, Singapore, Kuwait, Brunei, and Qatar. Fig. 2 shows this. Although Saudi Arabia still remains to be the favorite country of destination for OFWs, countries in Asia are slowly closing the gap, particularly, Hong Kong and Singapore where majority of the OFWs are females who are employed in the service sector. While more females went to Hong Kong and Singapore, more males went to Saudi Arabia and Japan. As of the year 2002, POEA (Philippine Overseas Employment Agency) statistics show that a greater percentage or 69% of newly hired OFWs are for all countries are females and they have dominated the professional (85%), clerical (63%) and service (90%) skills categories. Males, on the other hand, have dominated the administrative and managerial positions (66%), sales worker (52%), agricultural worker (97%), production (71%) and unspecified (95%) categories. This shows how the nature of work can still be highly gendered. Table 5 shows the complete data. Majority of the OFWs hail from the National Capital Region, Region 4 (composed of the Provinces of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Marinduque, Mindoro, Palawan, Quezon, Aurora, Rizal and Romblon), Region 3 (Bataan, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, and Zambalaes) and Region 1 (Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, La Union and Pangasinan). By province, the most OFWs are from Batangas, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Pangasinan, Rizal, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac and Isabela.

Some Socio-Demographic Characteristics of OFWs: Socio-demographic data of travelers will be limited to the Filipino contract workers abroad as similar data for other travelers are not available. Statistics for the year 1999 from the National Statistics Office (NSO, May 30, 2001) show that by age, the bulk of OFWs were aged 25 to 34 years old with females outnumbering the males in the younger age ranges (15-34 years 70 males for every 100 females). For the older age ranges, males outnumbered the females (196 males for every 100 females).

13 Table 5. Deployment of Newly Hired OFWs by Skills Category for the Year 2002

Skill Category Female Male 85,617 (85%) 14,968 (15%) 6 Professional and Technical Workers Administrative 129 (34%) 247 (66%) 1 and Managerial Workers Clerical 2.531 (63%) 1.508 (37%) 2 Workers Sales Workers 1,464 (48%) 1,605 (52%) 1 Service 88,669 (90%) 9,338 (10%) 9 Workers Agricultural 16 (3%) 601 (97%) 0 Workers Production 20,407 (29%) 49,476 (71%) 0 Workers For 590 (5%) 10,989 (95%0 0 reclassification* Total 199,423 88,732 2 Source: Philippine Overseas Employment Administration F/M Proportion of female to male OFW % - Percentage of row total * - Skill for reclassification

F/M

Total 100,585

376

4,039 3,069 98,007 617 69,883 11,579 288,155

In a survey done by the Bugna and Ybanez (2000) among respondents undergoing pre-departure seminars for OFWs, results showed that majority were Catholics, college degree holders and were single. The primary push factor for going abroad was economic in nature, citing the need to earn better income (71.8%) as the reason for seeking a job overseas. OFWs remittances as of 1999 were estimated at PhP 50.9 billion (NSO, 2001). Thus, they have been hailed as the mga bagong bayani ng bayan (new heroes of the nation) for bringing into the country much-needed dollars for the countrys economic growth.

TRAVEL AND SEXUALITY: Stoller (1977) had mentioned that sexuality is never about sex alone. The discourses on sexuality are wrought by discourses on power, structures and agency. Thus, there is a need to broaden our understanding of sexuality within the context of

14 changing social representations and meanings as these inform erotic imaginings in varying cultural contexts. The discussion below shows that a discussion on sexuality and travel both physical and in the cyberspace - also encompasses discussions on power relations within the contexts of race, income class, gender, culture and history. This study presents the vulnerabilities of travelers. This study focused on the sexualities of a specific group of overseas Filipino workers, the seafarers in the course of their travels to a foreign land, men having sex with men both in the context of travel and in the context of the Internet. Because of the nature of their work, which entails long periods of separation from the family which may reach for up to 2 years straight at a time, seafarers are vulnerable to loneliness, homesickness and depression. Stress from constant work in the ship further may fuel the desire to seek for means to address this loneliness. Being among the most highly paid overseas workers in the Philippines and being away from the surveillance of family and community; they have the economic power and the freedom to address their loneliness in whatever way they see fit. Moreover, because of their high incomes and high level of stress and loneliness entailed by their job, they have also become the target of sex workers willing to give them moments of pleasure for a fee. This study looked into how sexuality figures out in a seafarers life as he negotiates through troubling times in the high seas. Gay men and travel have been the topic of quite a few written works. Clift and Wilkins (1995) explained how travel has provided opportunities for gays to interact with other men in a socio-sexual way, which could not have been possible in their home environments. Moreover, the holiday mood while on vacation in a foreign land contributed to desire to seek new sexual encounters. Travel offers the gay male new opportunities for new sexual encounters and that crossing geographical boundaries potentially alter their sexual behavior oftentimes, leading to behavior that increases the risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, notably, HIV/AIDS (Herdt, 1997). Manalansan (2006a) provides a thick description of the life of Filipino gays who have crossed the Atlantic and established themselves in what is known as the land of milk and honey, the most aspired place to be in the world by many Filipinos - America. Being Filipino, gay and a migrant himself in New York City in the U.S.A., Manalansan looked into the lives of Filipino gay men in New York and his work contributes to the discourse on Filipino migration and sexuality. It is this work by Manalansan which this study drew mostly from to expound on the discussions presented herein. This study also covered individual interviews with three msm informants, two who self-identified as gays and one msm. For the interviewees, most of the occasions in which they had to travel to another country were work related. Short trips were necessitated by attendance in a conference, a workshop or a meeting. Longer periods of travel abroad were done mostly to complete a degree that added to their credentials for work advancement. In most of these travels, all interviewees admitted that there was the anticipation of a sexual encounter. Sex was never the main agenda for the traveling, but it certainly was part of the itinerary. All interviewees mentioned that when abroad they

15 would take the opportunity, whenever possible, to visit bars, saunas, and discos, movie houses, gay friendly malls, and massage parlors or simply to navigate through the gay cruising places. On-line chatters were also interviewed via the Internet. All the chatters were selfidentifying msm. The Asia-Pacific region is recognized as having the largest Internet users with an estimated 315 million users that is estimated to comprise 40% of the worlds households. The International Data Corporation (IDC) estimates that there will be 21.5 million Filipino Internet users by 2008 with an annual growth rate of 23 percent (Oliva, 2005; Villafania, 2005). This exponential growth can be attributed to several factors including the decreasing cost of services, aggressive marketing and continuing economic growth.

A. The Making of Desire The Desire for Adventure and Curiosity Desire for cross-border sexual relations is seen in as a product of the thirst for adventure and curiosity. To have a tikim (taste) of what is novel that travel to other countries can offer. For both the seafarers and the msm covered in this study the need to have a taste of what one cannot have back home is a motivation for them to seek for sexual relations abroad. Risk taking is part of the adventure and since sex in an alien environment may place an individual in a vulnerable position, sex becomes a necessary adventure. Moreover, being in a holiday mode while traveling may increase the mood to be more daring and take even greater risks for fun, to make the most of the trip and to stretch the limits of enjoyment derived from the travel experience.

Ang Pilipino talagang explorerlahat gustong malamanhe wants to experience the extremes( The Filipino is truly an explorerHe wants to know everythinghe wants to experience the extremes). A participant in a focus group discussion held among Filipino seafarers mid-2006 articulated this to describe the guts and daring of Filipinos in trying to make the most of his experience while at work in the seas. This guts and daring extends to the experience of their sexuality. For some of the seafarers in the FGD, joining the seafaring profession was motivated by the quest for adventure and the ambition to travel and see new, exotic places as well as take part in new experiences. For some, the compulsion to have sex with locals is strong and is articulated in the need to makatikim (have a taste of) not of the cuisine but of the local women. The desire to makatikim is articulated more within the context of paid sex and casual sex rather than sex that involved emotional ties. What Stoler (1997) calls the erotics of the exotic is what compels some of the seafarers to seek out sexual partners abroad. Tan (1998) wrote of ethnic distance and how this figured out in the production of desire for the other. Apparently, the degree of cultural difference defines how one finds the other, viewed as exotic and esoteric, as a sexually desirable object, hence, the need to have a taste of it.

16

Curiosity, particularly of what it is like to have sex with locals is a motivating factor for the seafarers to go to sex workers. For some of the men, their curiosity has been piqued by stories from others of their own conquests and exploits with local women. For the msm, when asked what draws them to seek for sex abroad, one interviewee, T35P, replied that para matikman kung ano ang delicacy ng bayan (to have a taste of the delicacies of the country), referring to the local people as some sort of food that had to be tasted. Manalansan (2006a:109) narrated how his respondent had the compulsion to have a taste of what was different or as his informants had put it kailangan mo naman tikman ang kakaiba di va! (You have to have a taste of something different!). E47P, mentioned that he always wanted to try new experiences and this was what would push him to seek sexual encounters abroad. Even locally, he had encounters with men of different ethno-linguistic backgrounds, once with an Aeta, also with a Kalinga, with what we can call as the cultural other or someone who was considered as different. Again, ethnic distance is a vital aspect in this instance. E47P was also thrilled in doing something he had not done or tried previously. The novelty of the experience is what he finds most appealing in his encounters. Thus, for E47P, having an air of mystery or the unknown in his sexual encounters is what he finds most enticing. E47P mentioned that the thrill of a sexual encounter especially one in which there is a danger of exposure or being viewed by other people is another factor that fuels his desires. The thrill of being caught appeals to him. He stated further that Pag pumunta ako sa ibang bansa talagang naghahanap ako. Sayang naman kung pumunta ka tapos wala (I always search for sex whenever I travel abroad. The trip would have been wasted if I dont have that experience). In a similar vein, T35P also mentioned that for him, kailangan mamarkahan ang lugar (he had to leave his mark in the place). For N30S, curiosity, particularly about how it feels to have sex with a foreigner is what makes the experience so desirable. Segregation and Separation Tan (1998) wrote of segregation and separation as part of migrant workers experience abroad. This refers to how a migrant worker feels when one is separated from ones family and feels segregated in the new place of work or residence by a culture one is unfamiliar with in which one does not belong to. He points to separation and segregation as producing feelings of homesickness and a longing for images that would in a sense bring back the homey atmosphere in a foreign land. It seems home brings with it feelings that are reassuring and calming. Hence, the search for romance and physical intimacy through sexual relations that would recreate the lost intimacy with a network of family members and friends left back home. Somehow, relations in such contexts compensate for the loneliness and emptiness of living alone in an alien environment. Away alone from home and hearth for months on end, seafarers have expressed the pain of having to contend with the loneliness and stress of living on the high seas (Osava, 2006). To alleviate the loneliness, they would turn to activities that would make

17 the separation from family less painful such as turning to forming relationships with women whom they meet when their ships dock on the port. Oftentimes, it is not just the need for sex that is addressed but also the need for what Osava (2006) calls normal relationships with other people probably those beyond the purview of work. Verghia (1998) wrote of how migrants develop social networks to address their need for warmth and comfort while in a foreign land. Sometimes, this emotional need is addressed by forming intimate bonds that include sex. In the FGD done with Filipino seafarers, all of the participants had resorted to commercial sex as a refuge or to develop a romantic relationship which they claim was the best way to alleviate their loneliness. It did not matter that they had to spend money for the kind of emotional satisfaction they craved. For the seafarers, money was just a tool that they wielded to experience affection, pleasure and satisfaction that brought about feelings of safety in an alien environment. Among the Internet users, a 33-year-old Filipino nurse exemplifies the homesickness experienced by many overseas workers. The following are excerpts from a YM on-line conversation involving the nurse: Nurse: Nurse: Nurse: Nurse: Nurse: Nurse: im from the province all of them are in fact in pinas im by myself here so chatting makes me busy alone but not really lonely I miss home

The new media technologies like the telephone, mobile phone and the Internet have made connecting back home possible albeit in a limited way instantaneous audioconversations, text messaging and more recently through the web cam technology of instant messaging and chat rooms. With the limited financial capacity of most OFWs who regularly remit part of their pay to support their extended kin in Manila, the new media technologies have been heaven-sent due to its affordability in maintaining connection with their loved ones Among the Filipino msm chatters based overseas, the Internet is the venue where they can relax after work or have fun while watching other chatters on the web cam. Connection also entails having the opportunity to converse in the vernacular with other chatters. In fact in this xxx-web cam chat room, Filipino chatters usually speak their own language regardless of polite requests from other chatters that English be used as the medium of interaction. Essentializing Maleness and the Political Economy of Desire Sexual encounters abroad are likewise, formed to reinforce notions of machismo. The study points to how, to some extent, the respondents have articulated the essential nature of men as being polygamous and how it is natural for men to need a woman by their side. Because of this, it is but natural for men to seek for suitable mates abroad especially when they are away from their spouses for extended periods of time. Feelings of machismo and male power are further enhanced by disparities in income class between the desiring male subject and the object of male desire. The role of the provider further

18 boosts the male ego in this instance. Within the concepts of masculinity or maleness, are strong underlying notions of the economics of desire. Examples to illustrate include the seafarers spending for the needs of their partners, the msms idealization of the bluecollar worker partner who would have to be dependent on him financially and the phenomenon of Western Unionism among chatters. All the msm informants mentioned that sex was done with greater frequency while abroad. This was because they had more time to pursue such activity there. Moreover, all three interviewees admitted to having multiple partners at a time. E47P claimed not be able to hold a long-term commitment because he easily gets tired of the company of one partner. Mas enjoy ako sa sabayan (I enjoy it more with several partners at the same time). He had also had the experience of an orgy with 3 men together at one time. E47P does have bouts of moral pangs from time to time. Nonetheless, he pursues the same lifestyle that he describes as hedonistic. E47P claimed that polygamous talaga ang mga lalaki (men are naturally polygamous), referring to the notion that men are essentially polygamous. Although N30S has had a steady partner for the past six or seven years, he claimed to have had other sexual encounters both locally and abroad. T35P has just started a steady relationship with a foreigner, though he used to have multiple partners, too. Before he met his current steady boyfriend he would have sex with a partner only once to deter any deepening romantic feelings towards one guy, thus, avoiding forming long term relationships. For the seafarers, emotional satisfaction was a strong need that had to be addressed. When asked why this need was addressed by entering into relationships, they said that because it was the instinct of the men, particularly heterosexual men, to find their mates. Nature yun. Gods creation, nga. Design talaga yun to find a mate. Ang lalaki di mabubuhay na walang babae. (It is the nature of men. Men were created this way. They were designed by God to find a mate. Men cannot live without women.). Apparently, finding mates as a consequence of travel to other countries was justified because it was the nature of men to have a woman always by their side. This brings to mind the biblical story of creation wherein Eve was created by God to keep Adam company. Moreover, for some of the seafarers, each port is an opportunity for conquest. Thus, they have earned the reputation of having a girl in every port. This reproduces the hegemonic stature of the heterosexual male seafarer and his foreign female sexual partner. Clearly, the seafarer is able to wield his greater power, one that is embedded in his positions of gender and economic status, as he negotiates over entitlements with his foreign sexual partner. Among the chatter-informants, some would openly advertise their services by posting messages or using chat names that indicate their availability for cash-for-sex. Oftentimes, they also include their contact numbers. On the other hand, clients also actively seek out pay-for-sex services sometimes offering money to those whom they desire even if the chatter is not necessarily into commercial sex work.

19 Of particular interest is the phenomenon of Western Unionism, which exhibits a negotiated exchange of desires mediated economically. Here, an overseas-based chatter, typically an OFW, would be enticed by a locally based chatter into an online romantic relationship. Once hooked, the OFW is besieged with indirect requests for financial or material assistance through stories of hardships, illness in the family and schooling needs. Remittances are then sent through Western Union, hence the term Western Unionism. In some cases, it is the OFW who offers financial benefits to initiate a relationship. Another aspect of the exchange is the willingness of an OFW to assist financially by offering regular allowances to their chosen on-line partner, being fully aware of the financial crisis in the country. These exchanges of economically mediated desires may be miniscule such as in the form of mobile phone load credits in small denominations. This extends to the Internet what Tan, Batangan and Espanola cited as the economic angle in relationships wherein low income males can derive some economic benefits from the neighborhood agi or bakla (2001:73)

The Community On Board Peer pressure also seems to be a strong push factor for seafarers to engage in sex with local women and this is especially true for first time seafarers who are on their maiden voyage. The ritual of binyagan (to baptize) has been a standing practice among seafarers and the older, more established seafarers would chip in to pay for the services of local sex worker who would service a new hire of the shipping company. For the new hire, the need to belong and be a part of the community on board, to join in the brotherhood and camaraderie, to take part in the acts of solidarity that will bind him to his shipmates is strong enough for him to give in to the pressure. Fear of ostracism and not to belong pushes a new hire to accede to the commands of his fellow seafarers, especially if it is his captain who gives the command. It could also be that this practice is an attempt to prove to one and all that the new hire is as macho as the rest, thus, reproducing the macho culture of seafaring. It must be mentioned that it was only very recently that seafaring has opened its doors to women. There are only a few Filipino women seafarers today. Strengthening male bonds is seen a strong factor among the seafarer informants for engaging in sexual relations abroad. Living for months or even years together on board a ship entails the need for the seafarers to bond together and develop camaraderie. This bond is forged by a common experience, some sort of initiation rite they call the binyagan. Forming ties with shipmates is necessary to ensure the development of a social support system among themselves when they are physically distanced from traditional support systems like their kin. Exposure to Different Sexual Norms Dislocation may expose a traveler to sexual norms that could be very different from those back home. This adds to the novelty, hence, the desire to try out how it is like to have sex that is free from restricting norms and inhibitions imposed on an individual in ones homeland. This may further encourage the traveler to be more experimental in his sexual exploits.

20

Among the msm, E47P has had the experience of traveling extensively in Asia and in Europe. He marveled at the openness with which other countries dealt with sexuality. For instance, in the Netherlands where he attended a short course, he had a sample of sex inside movie houses with strangers. He recounted how almost everyone else in the movie houses was doing it also. There, he shared, the movie houses specialized in showing specific themes such as bestiality, pedophilia, also msm. He was also able to witness a live show there. Such stuff may not be readily available in the travelers homeland. In the instances that these are, there was always the threat of a police raid, like in the Philippines. Hence, exposure to varied sexual norms and accessibility of new and exotic experiences and behaviors could somehow influence the travelers own sexual behavior. Technology, Mass Media and Desire The Internet was seen to have shaped desires and longings by expanding the horizons of its users beyond their immediate locations (Manalansan, 2006b). One of the interviewees, N30S, mentioned that it was always his fantasy to have sex with foreigners. His collection of downloaded porn from the Internet included photos of men of varied nationalities. Hence, N30S would actively seek for opportunities to travel internationally to fulfill his fantasy of having sex with foreign men. Of course, the Internet has opened new avenues for sexual encounters. Cybersex takes on many forms such as c2c (cam to cam), referring to using the webcam to show and to view Internet users masturbating or having sex with a partner. Moreover, seb orsex eyeballs are not uncommon after a brief encounter or introduction in the net. How the media like movies, books and magazines has constructed places appears to be an important factor in how travelers fantasize about spaces. For instance, travel magazines like Spartacus have promoted images of Thailand as a sexual space (Jackson, 1999). This has enhanced its desirability as the ideal place to be in for the traveler with sex in mind. Jolly and Manderson (1997:17), explained how the Longman dictionary defined Bangkok as a place where there are a lot of prostitutes. N30S shared that he would actively seek out sex while in Bangkok but not so much when he was in Vietnam or Cambodia. This is partly because he had known Bangkok to be a sexual space. This was not the case with Vietnam or Cambodia so his travels there did not have the anticipation of sex.

Trouble in the Home Front Away from home, the seafarer feels that since he has been working so hard he should be entitled to engage in certain activities that would allow him to alleviate his anxieties. Searching for sex is one such entitlement. One other factor that the seafarers mentioned that drove them to seek solace in other womens arms is when the wife is not able to handle well the remittances he sent.

21 There have been stories of seafarers coming home to huge debts accumulated by their wives. This is particularly heartbreaking for the seafarer who has toiled for a year or more, endured the homesickness of being separated from his wife and children and then coming home to find out that his family was still as poor as when he had left or even poorer as he finds creditors at his doorstep expecting him to repay the debts his wife had incurred while he was gone. This is one experience that drives him to go back to work promptly. Not only to earn more money to pay for the debts but also to escape the financial problems that awaited his return. With such situation in the domestic front, it becomes much easier for the seafarer to seek comfort from other women he meets abroad. Tales of seafarers leaving their Filipino families behind and settling with their foreign families abroad also abound. Just the same, the seafarers mentioned that they have to be matatag (strong willed) to fight the temptation the hound them abroad and to remain true to their marriage vows. Some of the seafarers attributed the ability to ward off temptation and longing to come back home to having a loving wife. One who was masinop (frugal) and malambing (affectionate). With a wife like that, coming home was done with much anticipation. Quite interestingly, the seafarers agreed that the mother-inlaw was also a crucial factor. A mother-in-law with a very strong personality could instill fear in the men and was a factor that constantly reminded them that they had to come home to their wives. Apparently, they feared that their mothers-in-law would report their wayward behavior to their employers and they would be barred from ever sailing again. In a private conversation with a seafarers wife, she confided that it was also not uncommon for seafarers wives to be involved in extra-marital affairs whilst their husbands are away. She had knowledge of stories of wives getting pregnant and attempts to hide this from their husbands. Apparently, loneliness is not the seafarers problem alone. Being in the Limelight Many of the seafarers have expressed liking the attention given to them by the sex workers who greeted them at the port whenever the shipped docked. They reveled in the fact that they were supposedly mobbed like movie stars even if they recognized that this was only because they were after the money they would pay them for their services. They said, Pag may pera ka, talo mo pa artista e, hinahabol ka! (When you have money you are like a movie star because you are sought!). This gives them a sense of importance and power, probably something they do not experience as migrant workers. Some of the informants had expressed that there was always the feeling of alienation and marginalization in the community that they visit. Among the chatters, exposing the body or performing sex acts to an audience through the web cam is met with great approval. Simultaneously showing the face while masturbating or having sex on cam could draw out praises for such acts are deemed to be a show of courage. Comparisons of their bodies and sexual prowess are inevitable and this performance is often seen as a competition. Wild teasing and insults are sent to those who do not surrender to the mob-like atmosphere of encouraging chat posts. These encouragements are usually posted in the form of wowowo, ahhh and other shrieks of

22 delight accompanied by adjectives such as sexy, nice, cool and other superlatives specifically for those who measure up to what could be considered as big or bigger than average body assets. Anonymity and Subaltern Identities Travel also gives the opportunity to perform acts or even identities one is constrained to perform in ones homeland. Abroad, one feels liberated enough to perform what could be construed as deviant or not acceptable to ones circle of friends in ones own country. Furthermore, abroad one becomes invisible. The anonymity that travel affords further contributes to the sense of freedom to do what one pleases as well as the confidence to perform subaltern identities. The anonymity that goes with being a foreigner in a foreign land was an advantage that made sex abroad desirable. For two of the msm informants, anonymity abroad was a huge factor that gave them the freedom from worries, that they would be recognized and would be talked about or become the object of tsismis (small talk). In the case of E47P, after an encounter with another male in the Philippines, which became the topic of rumormongers, he vowed that he would never engage in another blatant intimate moment with another male again within the country. Never again in his own backyard was how he put it. For T35P, it helped that he was not known to many abroad. The anonymity provided greater freedom for him to act naturally and to make rampa (to act freely as a gay person in public places). He claimed that he could be anyone and do anything that pleasures him. He felt more free to do stuff he would not normally do at home. He is able to explore other sides of his personality and is able to reshape his identity to anything that pleases him. He is able to indulge in activities that would be considered deviant in his homeland. T35P felt that back home such acts were not be acceptable to people within the circle he moved in. Manalansan (2006b) wrote of how sexual identity, practices and desires might serve as pivotal factors for migration and how travel could enable queer practices, identities and subjectivities that could not have been possible in the homeland. For the seafarers, the ship is a sexual space that allowed same sex sexual encounters at least for the duration of their contract even for self-identifying heterosexuals. In the cyberspace, anonymity in the Internet could provide a veneer of protection to those who wish not to reveal themselves. Chatters insult or challenge other chatters to show their bodies or faces. Such insults or flaming as they are otherwise called, may include branding another chatter who refuses to show his face as hipon (shrimp), particularly when the chatter has a muscular body and refuses to show his face. This is a pun on how shrimps are eaten by taking off the head and eating only the body. This implies that only the hipons body is palatable whereas his head is not as tasty. Nonetheless, the chatter can always opt not to reveal his face or body to the audience.

23

Holiday Mode Also, in the homeland, they would be busy with their work schedules and have lots of concerns; thus, they really do not have the time for seeking sex. Free from the usual concerns on domesticity while abroad, the traveler actually has more time to pursue sexual desires that he does not have the time for back home.

B. Embodiment of Desire This section will describe the object of the travelers gaze. This section will discuss what constitutes the sexually desirable partner from the point of view of the Filipino males. It is inevitable that this section would touch on what has been referred to elsewhere as a sexualized view of race as well as a racialized notion of sexuality (Cameron and Kulick, 2004; Stoler, 1997). Ethnic distance is another important factor is defining the desirable object. On one hand, there is the desire for the most other of all others or someone who was very much different physically and culturally. Thus, the desire for minority ethnic groups in ones own country or for those perceived as exotic in other countries. On the other hand, there was also the desire for someone who was very much like folks back home. The informants, both the heterosexuals and the msm, articulated racist notions of clean and dirty nationalities. Ethnic distance seems to be related to emotional distance, in some cases. This is evident in the preference for fellow nationals in forming romantic relationships in contrast with preference for foreigners for casual or one-night-only sexual encounters where hardly any emotions are involved between two individuals. Apparently, in some instances, the greater the ethnic distance, the greater, too, is the emotional distance. Of Potato and Rice Queens When asked what type they found most desirable, the msm interviewees gave varied responses. T35P, for instance, intimated that he really went for the big, white, hairy, potbellied, very much older white foreign male. Gays in New York as reported by Manalansan (2006a) also had the same type for a mate. T35P claimed to be a potato queen, referring to gay lingo for preference for the western type. For T35P it was prestigious to have a white Western boyfriend. This was considered as a good catch because you were able to attract a Westerner. The hegemonic East-West relationship is very strongly felt here. Moreover, T35P stressed that Filipinos were more maarte at mas sarado (more fussy and more closed minded) when it came to trying out unconventional sex acts, whereas, foreigners were more experimental and daring when it comes to trying out sexual positions and other sex acts. Filipinos were more pa-girl (assuming the coy female role in sex), thus, between two men having sex; no one would initiate a daring act in bed.

24

E47P, on the other hand was more of a rice queen which means his preference is for the Asian type. E47P also preferred younger men, with dark skin. E47P narrated that his personal history is a big factor in the shaping of his desires. He had gone underground during his youth, referring to joining a political movement that had fought actively against everything that the West, particularly what the United States stood for, hence, his aversion for the White Western type. In this instance, sexuality is seen as influenced by political tensions between countries. Both E47P and N30S also expressed preference for men with who had Arabian or dark Indian features. For E47P, it helped if the men were hairy, too. N30S shared a hierarchy of preferred races but hastily added that his preference ranking was not really rigid. His preferences are first Arabians, then Brazilians, Argentinians, Jamaicans, Filipinos, and Thais though not necessarily the Chinese type with a light skin tone but Thais with more traditional Lanna skin color. He liked the Indonesian type least. Both E47P and N30S mentioned that sometimes what they considered as ideal might not actually jibe with reality or whom they would actually have sex with. Oftentimes, they would have sex with whoever was willing and available.

Retaining Homegrown Ideals The seafarer informants claimed to prefer Indonesian women whom they saw to be very similar to Filipinas physically. Moreover, communication was not much of a problem because Bahasa Indonesia and Tagalog are very similar, both belonging to one family of languages. This made even moaning during sex easier to appreciate. Even among the msm group interviewed and the Internet chatters, partners may be chosen based on degree of similarity on the physical side. Racist notions of clean and dirty nationalities were also articulated. Preference for fellow Filipinos as sexual partners even abroad reflects the strength of the ethnic divide as a guiding principle for selection of partners. In identifying preferred sexual partners, a sexualized view of race is exhibited. Even in performing sexual acts, notions of clean and dirty become operative. To illustrate, some of the respondents claimed to be more experimental with sex workers or with foreign partners than with Filipino partners in the Philippines. On the other hand, some of the seafarers, though, more daring acts like oral sex must only be done with their wives who were viewed to be clean. Again, notions of the locale and sexual norms are implicated here. These notions are deemed to be significant, particularly, on where implications to sexual and reproductive health are concerned. Among Southeast Asians, Filipino seafarers preferred Indonesians. As with the Brazilians, Indonesians look very much like Filipino women in skin color. The language is even similar so communication is not much of a problem. In fact, one FGD participant added that even the moans in bed were also very similar. Thus, they are reminded of home. Homesickness then becomes a non-issue. They are also treated well by the Indonesian women who were described as malambing (affectionate), mapagsilbi (serving) and mapagmahal (loving). They would do the laundry for the men even remove the bones of the fish and feed them. One participant narrated his experience of having a long-term relationship with an Indonesian whose whole family would greet him

25 and treat him well whenever he was in Indonesia. This, somehow, eased the pain of separation from family and friends. Of course, the seafarer treats the woman and her family well as well by giving them gifts and cash that would also alleviate the sufferings of the woman who are economically deprived. The seafarer becomes her savior from a life of despondency. Similarly, Hamilton (1997:152) had written of how wealthy foreign men would launch himself into campaigns of salvation of the woman referring to female Thai sex workers. The wealthy foreigner does this by showering the Thai woman with gifts, sometimes offering sums of money on a regular basis to get her out of the bar scene, hence, the foreigner is sees as a savior. Interestingly, the seafarers recounted paid sex encounters with fellow Filipinos abroad. In Singapore, Filipina domestic helpers have approached them offering sex for hire. Some would even be bringing their small children with them when they approached the seafarers. Often they would give in because of the desire to help their fellow Filipinos. The perception is that they are in sex work because they have a great financial need. This is the saydlayn (extra income generating activity) of some of the overseas Filipino domestic helpers. Similar experiences with Filipino domestic helpers in Hong Kong were narrated. The urge to help a kababayan (country mate) is especially strong particularly in a foreign land. It seems that love of country and country mates, their identity as Filipino, is more astute outside the country than within. The preference for fellow Filipinos by the seafarers has encouraged Filipinas abroad to enter sex work, which has become a lucrative saydlayn for them, especially when fellow Filipino seafarers were concerned. The seafarers unanimously named the Filipina as the preferred type over all other nationalities both for paid sex and for romantic relationships even while abroad. They felt that Filipinas were malinis sa katawan (clean bodies). Therefore, the perception is that they were free from disease. Similarly, pregnant Brazilian sex workers were much sought after by Filipino seafarers, because they were believed to be malinis (clean). Sexually transmitted infections contracted from Korean and Chinese sex workers were perceived to be incurable so dealing with them was done with caution. Greeks were said to be mabaho (with foul body odor) because they were said to have profuse body hair, which trapped bacteria that caused the body odor. In here, the ethnic divide becomes even more acute. It is likewise vital to point out that notions of clean and dirty would have implications on the whether the seafarer would practice safer sex practices or not. In the case of Filipina partners, in particular, some Filipino seafarers will not use a condom with them even if it was a paid sexual encounter.

Among the msm, preference for fellow Filipinos for long-term relationships was expressed by N30S because of what he identified as the cultural factor. He felt that it was much easier to keep a relationship with a fellow Filipino because it was easy to understand each other and there was not much of a cultural gap. Foreigners were okay for short-term sexual relationships or for one-time sexual encounters but fellow Filipinos were boyfriend material. E47P, likewise, preferred Filipino or Asian partners. He found them to show more emotion in the relationship. They would send sweet messages

26 through texting such as luv u (I love you) or mis u (I miss you). His experiences with western partners were more physical and lacking the emotional aspect. He also prefers a more open relationship with his partner. One with whom he would be able to disclose his other sexual exploits. Within the context of the Internet, Brah (1996 as cited in Kuntsman 2003:6) wrote of homing desire and defined this as the desire for a place of belonging which is homey, yet is not necessarily located in ones homeland. The phrase could very well explain the propensity of respondents in the Sangil-de Luna (2001) and Billedo (2004) studies to choose people who were similar physically and the possibility of such relationships to progress to a more intimate level. Manalanzan (2003:14) similarly demonstrated that emigration and the multiple displacements associated with it brings about the task of creating and refiguring home. Claiming Local Symbols N30S explained that when in Bangkok, he was drawn to the youthful, slim bodied, almond eyed, dark skinned, typical Thai male. He admitted, though, that this typology was largely influenced by the media ideal portrayed in the celebrity magazines, television programs and billboards he came across in Bangkok. Thus, desire may also be media mediated. T35P, who like N30S, also did some post graduate studies in Bangkok, also narrated that he had the same preference, but only while in Bangkok. He hastily explained that this was actually patterned after the local Thais own notions of what was the ideal. E47P, who also had gone on several trips to Thailand shared that he had the same ideal type while in Bangkok. Preferences for a particular type can be transformed once one gets to another country. Apparently, the ideals of another culture are imbibed and replace ones ideals from the homeland. Fantasizing the Hypermasculine Male Cameron and Kulick (2004), had shown how class differences can be eroticized. In this study, E47P emphasized that it has always been his fantasy to have sex with the typical blue collar worker type one that had dark skin from working under the heat of the sun, all sweaty from performing manual labor and with a muscular frame developed not in the gym but from toiling day in and day out using his brute male force, someone like a construction worker. N30S expressed liking for the same type. Apparently, for both E47P and N30S this type represented the quintessential male. Laboring over a male only job was lalaking lalaki (very male). This was how they both described the job and the body type. Both N30S and E47P admitted that there was an underlying power dimension in preference for the laborer type. N30S liked it that these men would be dependent on him financially because he was a professional and had greater economic means. It seems that income class is also a vital aspect of sexual desire, whether in Philippines or abroad. Similarly, Manalansan (2006a) reported that Filipino gays in New York felt that their partners financial dependence on them added to their machismo and that it was okay for them to pay for their men. In such cases, the material power of money is extended to realms of love, nurturance, pleasure and control.

27

Off to the Gym: Displaying the (Male) Body As the technology of the live web cam is readily available in cybercafes, chatters can show their faces and bodies to give a more complete picture of them. The new media technology has extended the space for displaying the male body in a more risqu form, which may not be possible under other circumstances. Thus, it is important to view the online discourse in relation to how bodies are displayed and talked about and how it relates to dimensions of power and class. Preference for the muscled male body is gauged by the reactions from viewers whenever they encounter a buff chatter. Huge biceps, muscular chests, lean or welldefined abdomens in poses that accentuate the muscular details bring our compliments from the audience. This is not to say that ones face in not important as several studies have shown that an attractive face is one of the attraction cues (Sangil-de Luna, 2001; Angeles-Lorenzana, 2004; Billedo, 2004). This is exemplified by The Angel is Back, one of the more popular chatter and a gym instructor, who has installed a spotlight in his room for his web-cam shows. Thus, an oft-repeated statement one encounters in the chat room is about the gym where one goes or what one does. Going to the gym conveys the message of how the body is worked out, developed and displayed. The gym has become an indicator of ones socio-economic status since membership fees go way beyond the economic means of many Filipinos. Logging off to go to the gym has become part and parcel of the on-line discourse. The males obsession with their bodies has been termed as the Adonis Complex (Pope, Olivardia and Phillips, 2002), wherein men go on an almost limitless number of strategies to deal with their insecurities (Brown, 2005:199). Never in My Dreams Among the msm, racial types that were not preferred were the black Americans and the Indonesians. E47P also intimated that he has an aversion for uncircumcised men, claiming that it was yucky to perform oral sex on uncircumcised men. OFW chatters share the same sentiment. Ayaw ko sa supot (I do not like uncircumcised men) or sawa na ako sa supot (I am tired of uncircumcised men) were remarks noted in a chat room. E47Ps preferences and image of an ideal partner should approximate the Filipino cultural ideal, which is the mestizo type though not pure Western looking; definitely not the blond and blue-eyed type. Manalansan (2006a) likewise, reported that Filipino gays in America have shown aversion to the black American types. Aversion to very dark skin like that of an African American is strong even among other Filipinos in the Philippines. This is a part of the colonial legacy from the Spanish period that promoted Castilian features as standards of beauty. Skin color also matters in cyberspace. It was noted in a few instances that chatters who were darker skinned compared with others were relatively ignored.

28 E47P also mentioned that in looking for a partner, he consciously avoided the big, burly type because of a previous untoward incident. He had the experience of being mugged by a big man who had seduced him into thinking that the guy was eager to have sex with him. They went inside a public toilet and in the privacy of the toilet; the guy forcibly took his expensive watch from him. From then on, E47P was more cautious in choosing his partners. Preferably, he would pick up the ones who had a smaller body frame than his so he could easily overpower them.

C. Sexual Acts Reinforcing Gender Scripts What one of the seafarers called as the love language seemed to be a vital factor in their romantic relationships with foreign women. The ability to connect not only physically but also linguistically and emotionally was important to them. Sex is more satisfying when done in the context of a loving relationship so it was not uncommon for them to forge romantic relationships with the women even if the relationship started as a paid sexual encounter. Furthermore, romantic relationships were formed because once a relationship gets to the boyfriend-girlfriend stage; payment for sex was no longer part of the script. They no longer had to pay for the sexual services of the woman, so they were nakakalibre (sex is free). The seafarers acknowledged, though, that the relationship based on romance ended up as more expensive to maintain than a one time sexual encounter. In a long-term relationship, the seafarer had to pay for the needs of the woman, which oftentimes, included the needs of her family. Nonetheless, they had the money so they would often opt for the romantic relationship even if it were more costly for them because of the emotional factor, which can never be present in a hurried, paid sexual encounter. Apparently, sex is much sweeter when done within a romantic relationship. In a similar vein, Hamilton (1999:149) wrote of how part of the attraction of the Thai sex worker would be her ...willingness to carry out tasks associated with nurture and caring behavior. Loyalty seems to a vital aspect of the sex worker-client relationship, even if the relationship has not moved on to the boyfriend-girlfriend level. The sex worker would remain loyal to the seafarer client by not taking other clients as long as the seafarer doesnt act like a butterfly. This the metaphor used for a man who patronizes several sex workers akin to a butterfly alighting from one flower to another. Most of the seafarers also preferred this arrangement. There were stories of shipmates engaging in squabbles over one woman. The relationship between the seafarer and his partner reinforces heteronormative scripts between men and women and is laden with great inequalities in power, for instance, the economic dependence of women on men and the demand for loyalty on the part of the men. This shows how gender power relations shape desire and maintain the dominant gender order. Eckert (in Cameron and Kulick, 2004) supports this claim.

29 Health wise, however, romantic relationships were less safe sex encounters than paid sex. Because the relationship is now based on love, using condoms was no longer practiced. Paid sexual encounters were relatively safer than relations based on romance because the seafarers tended to use condoms in paid encounters. Thus, emotional distance is also a factor in determining whether a seafarer will practice safe or unsafe sex. It is also worth mentioning that shipping companies and the government have started to enforce more stringent measures to promote safer sex practices among seafarers. Predeparture orientation seminars now include HIV/AIDS prevention messages. Shipping companies always carry a stock of condoms on board each vessel. Mandatory health check-ups that would often have HIV testing were enforced before a contract is finalized. Furthermore, the AB or akyat barko has been banned, particularly, after the 9/11 incident in the U.S. as part of counter-terrorist measures. In AB, sex workers would climb the ship to gain access to the rooms of the seafarers and have sex. All these have somehow influenced seafarers to practice safer sex in certain contexts. Gendered scripts are also exhibited on-line. One often encounters questions as to whether one is a top or a bottom, referring to the position one takes while doing the sexual act, also, whether one is effem (effeminate) or straight acting or discreet for the msm. Chatters refer to each other as bro (slang for brother) and tol (short for utol which is slang for brother) or pare (short for kumpare referring to the tagalog term of reference for ones childs godparent). Use of these terms set the context of the relationships of the chatters and tells about the chatters self-representation on-line. Some pronouncements made are also meant to display the chatters virility through references to his capabilities for multiple orgasms within a day, his sexual exploits and a host of other activities. Sexual Acts and the AIDS Scare For the long-time seafarers, those who were in the trade for more than twenty years, their sexual behavior could be delineated as pre-AIDS and post-AIDS. Before the massive campaigns against HIV/AIDS, they admitted to more wanton sexual behavior pukpok lang ng pukpok (just keep on having sex) was how they described it. This was in the 1970s and into the early 1980s. With the AIDS scare, however, they have learned to be more discriminating. Certain sex acts are now reserved for the missus; for instance, oral sex is seldom performed on sex workers. There was, however, disagreement on this aspect of the sexual act. For some of the FGD participants, performing unusual or nonconventional acts with the wife should not be done. Some degree of deviance is associated with these acts and should be done only with a sex worker. For instance, one participant quoted a Brazilian sex worker welcoming Filipino seafarers on the port with the greeting Hola, Pilipino! Brutsador! Vamos, mucho amor, para tumba la cama! This may not be the exact phrase uttered but this is what of the seafarer informant recalled. In the greeting, the Brazilian sex worker was referring to the Filipino as a performer of oral sex, particularly, cunnilingus, by calling him brutsador. She was also urging the Filipino seafarer to go to bed with her as her lover. For the seafarer this meant an anticipation of wild sex in bed.

30 All the msm interviewees felt that one should always practice safe sex with a foreigner. N30S said that this was a rule he used especially with a white western male. The perception was that white western males were more promiscuous and contracting from them an STI, or worse HIV/AIDS, was more likely. T35P always uses a condom whether locally or abroad because he felt that one could never be sure with a partner. E47P, on the other hand, never engages in anal sex. Fellatio was the most he has done with a partner. He considered anal sex as dirty.