Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

James Madison Republican or Democrat by Robert A Dahl

Cargado por

coachbrobbDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

James Madison Republican or Democrat by Robert A Dahl

Cargado por

coachbrobbCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

James Madison: Republican or Democrat? Author(s): Robert A. Dahl Reviewed work(s): Source: Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Sep.

, 2005), pp. 439-448 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3689017 . Accessed: 22/06/2012 11:41

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives on Politics.

http://www.jstor.org

Articles

Madison: James Democrat? or

Robert A. Dahl

Republican

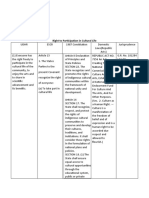

in the Federalist, as he gainedgreater in the new experience AlthoughJamesMadisonis best known for the views he expressed fourpropositions: someof theseearly viewsandincreasingly American threat (1) thegreatest emphasized politicalsystemhe rejected not the majority; of the in theAmerican comesfroma minority, (2) to protecttheirrightsfromminorityfactions,members republic might threatenproperty rightscould be majorityfactionmust organizetheirown politicalparty;(3) the dangerthat majorities a feasible solutionin America; and (4) in a republic, of citizensto own property, overcome must majorities by enablinga majority wereflawedin at leastthreeseriousways:(1) as an EvenMadison's be allowedto prevail. views,however, post-1787 constitutional is contradicted thedanger offactionalism hisconjecture thatincreased sizereduces bysubsequent experience; empirical proposition, and (2) in his conceptionof basic rights,Madisonexcludedmore than half the adult population:women, AfricanAmericans, in the Constitutionthatgaveto slavestatesan increase in representhe provision American and (3) he activelysupported Indians; of the slavepopulation. tativesamountingto three-fifths

a lecturethat earlyhalf a centuryago I published

was highly critical of what I called "Madisonian Democracy."1Now I find myself both more sympathetic with Madison and more critical. I'm more sympathetic becauseI've come to understandhow experience with the rapidlyemergingAmericandemocracyled James Madison to views that I would regardas somewhat more democraticthan those he expressedat the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and soon thereafterin the Federalist. I'm more critical because of his willingness to exclude a very large part of the adult population from enjoying the rightsof citizensin the politicalsystemhe helped to create. Despite my criticismsof Madison, I beara deep respect for the depth and range of his understandingof political Robert A. Dahl is the SterlingProfessor Emeritusof Political Scienceat YaleUniversity A (robert.dahl@yale.edu). Association, pastpresidentof theAmericanPoliticalScience his numerous publicationsincludeA Prefaceto DemocraticTheory; Who Governs?Democracy and Powerin an AmericanCity; Democracy and Its Critics;and How Democratic is the AmericanConstitution? Theauthor his appreciation to the PoliticalScienceDepartexpresses mentsof the University of Indiana and StanfordUniversity to offera lectureon the subject for providingopportunities this and to of essay profitfrom the discussions thatfollowed. Thanksalso to Professors Mathews, JackRakove,Richard and LymanT Sargentfortheir helpfulcriticisms and on a this suggestions draftof paper.

life and his constantsearchfor propositionsthat roseabove the level of descriptionto reacha higher level of generality. In this sense he was a distinguishedpolitical scientist. Even more, his capacityfor modifying his earlierconclusions through laterobservationsgave him the perspective of a true scientist of politics. Yethis view of politics went beyond empiricalobservations. For his interestin politics was profoundlyanchored in concerns not only for what was, but also, in his view, what ought to be. His lifelong effoit to understandpolitics was clearlymotivatedby a desirethatAmericansmight achieve a good polity. In Madison'sview, a good polity for Americanswould necessarilybe a government that derived its just powers from the consent of the governed, or, as we might say today, a democracy.His role in the evolution of democraticideas and institutionswas extraordinary. By his creativeleadership at the American Constitutional Convention in 1787 and his persuasivecontributionsto the Federalist he helped to inaugurate one of the immediatelythereafter, most fundamentalchanges in democraticideas and practicesthat hasoccurredoverthe entirehistoryof this ancient form of government.Henceforth,"government by the people"would no longer be restrictedto assembliesof citizens in smallunits like city-states. Nor would the rightto choose to representatives legislaturesin largerunits be restricted to an exceedingly tiny number of men drawn from the privilegedfew, as it then was in the parliamentsof Britain and Sweden.Judged from this perspective,Madison was, in his own cautious fashion, a revolutionary. September 2005 I Vol. 3/No. 3 439

Articles I James Madison: or Democrat? Republican

Yetifwe wereto judgeMadison by standardswidely used today in determiningwhether ..... alargepoliticalsystempossesses ........ . all the institutions minimally .. necessaryfor it to be considered a democracy, we would .| . .. : i": haveto conclude that when he ' attendedtheAmericanConsti........... tutionalConventionandwrote in his essays for the Federalist . i :'; .:. . :'.'.;-. . . ";i:i " . .' ..:;. ..... ! 1787, he was not much of. a democrat. As readersof his well-known contributions to '^'.::the Federalistare aware, he .... 4 ' even insisted that the term democracywas not appropriate for the governmenthe envisioned. Instead,it should be designateda republic. In the years following the convention and the Federalist, i as he engaged in the ongoing . g projectof creatinginstitutions |...... ..S necessaryfor a people to self', .'... govern, Madison began to expressviews that were more . :; "democratic" than those he had announced earlier. We .... might think of the views he .::.: :;!: presented at the convention and in the Federalist s com'.: :.' posing his constitutional. ;:i theory of 1787, while his later.. views expressedhis post-1787 i

constitutional theory.2 A stun-

,.:

:: ;:

ning instanceof the shift from the first constitutional theory to the second is his role in the . Si' *" formation of the Republican Party. Yeteven in his post-1787 constitutionaltheory,the more democratic Madison endorsed views and practices that were far less acceptablydemocraticthan those that would come to prevailduring the next two centuries.

r _

The Man

When the Constitutional Convention assembledin 1787, Madison was only thirty-six."Atfive feet six and less than 140 pounds," one historian has written, "'little Jemmy Madison' had the frail and discerniblyfragileappearance

of a ... schoolmaster, forever lingering on the edge of

some fatal ailment."3With his modest statureand rather high-pitched voice, he was hardlyan imposing orator.Yet 440 Perspectives on Politics

the knowledge he brought persuasivelyto bear on the issues, together with his gentleness and fair-mindedness, made him probablythe single most influentialmemberof the convention. With a BA at twenty from the College of New Jersey (Princeton), at twenty-five he was a delegate to the Virginia Convention, at twenty-seven acting secretaryand memberof the VirginiaCouncil of State, at twenty-nine a delegate to the Continental Congress, at thirty-three a memberof the VirginiaHouse of Delegates, and at thirtyfive an appointee to the Annapolis Convention. In preparationfor the ConstitutionalConvention at Philadelphia, he undertook a study of "ancientand modern republics wrote a brief [and] ancient and modern confederacies,"4

note entitled "The Vices of the Political System of the United States,"and drew up the essentialsof what would shortly be introduced at the convention as the Virginia Plan for the new constitution.5 At the age of thirty six, James Madison was better preparedfor a constitutional convention than most American political leadersof later generationswould be at fifty-sixor sixty-six.

Madison's Four Questions

Madison's most influentialviewswere,and aretoday,those he expressedin the Federalist, 10 and notably in Federalist 51. Few persons, including most political scientists, I believe, have paid sufficient attention to the important ways in which he modified these views as he gained experiencewith the political system that he helped so much to create.6 At the ConstitutionalConvention, in the Federalist, and in letters and other writings of the time, Madison regularlysought to answerfour questions: 1. What is the new system of governmentto be called? 2. Does a common good exist and, if so, can we know what it is? 3. What are the major threats to achieving the common good? 4. Can these threatsbe overcomeand, if so, how?

A Republic or a Democracy?

Madison said, he meant "asociety By "puredemocracy," consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person...." Democracy thus defined-pure democracy-stands in contrast to "arepublic,by which I [Madison] mean a government in which the schemeof representation takesplace... [and] ... the delegationof the government... [is granted]to a small number of citizens elected by the rest. . ."7 In advancingthis definition,Madisonconfronteda genuine problem. In the eighteenth century no generally acceptedname existed for the kind of governmentthat he and his contemporaries werestrugglingto create:a government that acquiredits legitimacyfrom the sovereigntyof the people, but in which the people would govern indiwith the power to enact rectly by electing representatives the laws.Although classification schemesfromAristotleto Montesquieuwere often presentedwith more nuance and subtlety than I need to explore here, a common practice was to divideconstitutionsor politicalregimesinto the rule of the one, of the few, or of the many,each of which might be divided in turn into good and bad forms, dependingon whether the rulerssought to achievethe common good or merelytheir own interests.The good and bad formsof rule by the one were monarchyor despotism. Rule by the few would be aristocracy or oligarchy.What about rule by the many?Should the good form be called a democracyor a Wha about t the bad form? republic?

Around 400 BCE the Athenians, drawing, naturally, on theirown language,chose to call theirsystema "democracy,"from demos("thecommons," or "thepeople") and kratos("rule,""sway," or "authority"). At about the same time, the Romanscalled their system a republic,from the Latin res,thing, affair,and publicus,public. In the thirteenth century,when the Italiancity-statesof Venice, Florence,Siena, Lucca,Genoa, Bologna,and Perugiaadopted constitutionsprovidingfor a measureof self-rule,they all, of course, drew on their own language and history and called their governmentsrepublics. The difference in word usage boiled down to language,not politicalinstitutions.Yetwhethercalleddemocraciesor republics,the political systemsof Athens, Rome, and the Italian city-stateswere totally inappropriatefor eighteenth-centuryAmerica.To be sure, along with their citizenassemblies, the Atheniandemocracy and the Roman had some elements of republic representation.But by no stretch could their political systems serve as models for a representative government in the United States of America.As for the Italianrepublics,they may have been aristocraticor oligarchic republics, but they were definitely not democraticrepublics.8 To add to the confusion, the two terms-democracy and republic-were, it appears,commonly used more or less interchangeably among Americansin the eighteenth who weremorefavorcentury.9 My guessis thatAmericans able toward rule by the people tended to use the term democracy,while those who were more dubious preferred the term republic. In any case, Madison'sfamous distinction between the terms democracy and republic was somewhat arbitrary and ahistorical. Evensome of his contemporaries, likeJames Wilson, referredto the new representativesystem as a democracy.10 The term democracysoon came into general usage.l The Republican Party,founded by Jeffersonand Madison, was swiftlyrenamedthe DemocraticRepublicanParty and its successor,in 1828, the Democratic Party. Tocqueville'sfamous volumes published in 1835 and 1840 were, 12 as we all know, named Democracy in America. The plain fact is that JamesMadison has decisivelylost the battle of terminology.13I would dismiss the whole question as trivial if it were not for the frequencywith which I have encounteredthe assertionthat the founders createda republic, not a democracy.One could interpret this to mean that by excluding more than half the adult population from the rightsnecessaryfor a system to meet today's democratic standards, the founders created an oligarchy-an oligarchic republic, if you will, not altogether unlike the medieval Italian republics.But it is my impression that those who make this claim want to use the authority of the founders to reject the legitimacy of as an appropriate standardfor contemporary "democracy" America. To which I would like to reply, if the United

September 2005 1Vol. 3/No. 3 441

Articles I James Madison: or Democrat? Republican

States is not, and should not be, a democratic republic, then what kind of republic is it or should it be? An arisAn oligarchicalrepublic? tocratic republic? Let me now turn to Madison'sresponseto the second question; Does a common good exist and, if so, can we know what it is?Adopting a view that was common in his time, Madison assumedthat a common good existed and could be definitely known, at least by some. Yet despite Madison's confidence, after two millennia philosophers continue to disagreeover two centralissues.Just how can we knowwhat the public good truly is?And what persons would be most likely to know and actuallyseek to achieve the public good? As to the first issue, is knowledge of the public good self-evident?If not, can it be derivedby pure reason, and perhapsonly by pure reason, as Kant would If pure reasonis insufficient,does knowledgeof the assert? public good depend on intuitions?On feelings and emoAll of these? tion? Experience? Madison's he camedown firmly positionwasunequivocal: on the side of reasonand, like Kant, refusedto allow any Here, Madison'sunderplace for emotions and passions.14 to of human nature seems have deserted him, which standing is particularlysurprising because his view flatly contrabefore dictedthatof DavidHume,whoseworkhe hadreread on attendingthe conventionandwhoseargument the advantages of size for reducing the evil effects of faction anticiBecausethe physiologicalconnections pated Madison's.15 between reasonand emotion were largelyunknown until the late twentiethcentury,asepticviews like Madison's and Kant'swere beyond effectiverefutation.In light of what is known today, however,the assumptionthat reasoncan be from emotion appearsto representa funwholly separated view of human nature.16 mistaken damentally to havebelieved, As to the secondissue,Madisonappears not unlike Plato, Confucius, and many of his contemporaries,that certain persons of greaterwisdom and public virtue might know betterthan otherswhat the public good truly is, and would also be more inclined to act on it. A crucialadvantageof a representative republicoverdirector Madisonasserted,is that the requisite assemblydemocracy, wisdom andvirtuearemorelikelyto existamongthe elected than among the people who elect them. In representatives 10 he wrote that the effect of elections is Federalist themthrough thepublic to refine andenlarge views, bypassing whosewisdom of a chosen the medium may bodyof citizens, it to willbe least to sacrifice andloveof justice likely patriotism it sucha regulation, considerations. Under orpartial temporary thatthepublic voice,pronounced by therepmaywellhappen to thepublic consonant of thepeople, willbe more resentatives convened for themselves bythepeople goodthanif pronounced thepurpose. (Myitalics) Madison was too experienced in the ways of politics and politicians to assume that this desirableoutcome was inevitable,and he immediatelyadds a realisticqualifier: 442 Perspectives on Politics

and whose best discern the true interests of their own country, On the other hand, the effect [of elections]may be inverted. Menof fractious of localprejudices, or of sinister tempers, designs, or by other means,firstobtain may,by intrigue,by corruption, the suffrages, and then betraythe interests,of the people.17

Beforeturning to Madison'ssolution to this dilemma, I want to underscorehis implicit assumptionthat the "public good," the "interests of the people,"could be definitely known and described.If Madison were alive today, I find it hard to believe that he would advancethis assumption as if it needed no furtherjustification.Today'sMadison would surely ask a question like this: In concrete situations when people disagreeabout the public good, as they commonlydo, how can we knowwhat is best?In Madison's own time, didn't the interestsof slave owners, including enlightened slave owners like Madison himself, conflict with the interests of others-not least, of course, those who were enslaved? Don't basichuman rightstrumppropOr are erty rights? property rights inviolable even when violate fundamental human values? they If some citizens believe that their interestsconflict with the interestsof others, how should the matterbe decided? What is the properplace of public deliberation,and how is it to be achieved? When interestsconflict, should we be the utilitarianformula of "the greatergood of guided by the greaternumber,"and if so just who constitutes the "we"entitled to make that decision?Or, given the pitfalls hidden in that formula, should the decision follow some other moral principle?If so, what? And just what is the legitimate role of majorityrule? Even if Madison'sassumptionsabout the public good may have been persuasivein his own time, today his contention that the public good can be definitely known by elected representatives would scarcelybe debated. This leads me to my third question. In Madison'sview, what arethe majorthreatsto achievingthe common good? In his 1787 constitutional theory Madison was primarily concerned, I think, with two of these. One I have already mentioned: "Men of fractious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may, by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages[votes], and then betray the interests, of the people." His main solution to this problem of leadership-a solution widely supported by his colleagues at the convention-was the famousseparationof powersinto the differentbranchesof government that would serve as checks and balances. BecauseI want to focus here on some changesin the views Madison came to expressas he, the country, and indeed the world gained more experiencewith large-scalerepresentativegovernment,I'll say no more about this solution and insteadturn brieflyto the other majorthreat:factionalism. "By a faction," he wrote, "I understanda number of citizens, whether amounting to a majorityor minority of the whole, who are united and actuatedby some comto the rights mon impulse of passion,or of interest,adverse interests of othercitizens,or to thepermanentand aggregate

Where liberty exists, factions are inevof the community." itable. "Aslong as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at libertyto exerciseit, differentopinions will be formed.... The diversityin the facultiesof men. ... [is] an insuperableobstacle to a uniformity of interests.... The latent causesof faction arethus sown in the natureof source and durable man .... [T]he mostcommon offactions and unequaldistribution has beenthe various ofproperty."18 How might the dangersof faction be mitigated?"If a faction consists of less than a majority,"Madison wrote, "relief is suppliedby the republican principle,which enables the majority to defeat [the minority's]sinister views by vote."19But what if the factionwere itselfa majorregular he wrote to Jeffersonin 1788, "In our Governments," ity? in lies the "the real power majority in the Community, and the invasion of private rights is chiefly to be apprehended, not from acts of Government contrary to the sense of its constituents, but from acts in which the Government is the mere instrument of the major number of the Constituents."20Like many of his colleagues at the convention, and the classicwritersfrom Aristotleonward who had helped to shape their views,21Madison believed that the greatestthreatto fundamentalrightswould come from majoritiesof citizenswho possessedlittle or no property. For if the many lacked property,they would, driven by the overpoweringforce of self-interest,surely attempt to infringe on the propertyrightsof the few who did own property. Turning to Madison'sfourth question, if factions that threaten the basic rights and liberties of others are inevitable, what is to be done? A Bill of Rights, Madison believed, might be helpful, but it was not sufficient."My own opinion," he wrote in his letter to Jeffersonin 1788, "hasalwaysbeen in favorof a bill of rights ... At the same time I have never thought the omission a materialdefect, nor been anxious to supply it even by subsequentamendment, for any reasonother than that it is anxiouslydesired by others. I have favoredit becauseI supposedit might be of use, and if properly executed could not be of disservice." He was lukewarmabout its necessityand doubtful about its effectivenessbecause"experience provesthe inefwhen it is on of a bill of those occasions ficiency rights most needed .... Repeatedviolations of these parchment barriers. . . have been committed by overbearingmajorities in every state."22 Was Madison'searlyfearof majoritiesinfluencedby the possibility that they might threaten the one form of property-slavery-that was essential to his livelihood? Whateverthe reasons,in his earlieryearsMadison clearly feared that government by majorities might seriously endangerthe rights of minorities. So what was to be done? Madison'ssolution included severalelements:federalism,a constitution of limited enumeratedpowers, and, as I have mentioned, the election of But Madison'smost original contriburepresentatives.23

tion, the one for which he is probablybest known and for which he has been cited endlessly,was to enlargethe size of a republic. "Extendthe sphere,"he asserted,"andyou take in a greatervarietyof partiesand interests;you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens;or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discovertheir own strengthand to act in unison with each other."24Increasingthe size of the system, then, was "a republicanremedy for the diseases Was Madimost incident to republicangovernment."25 son correct?I'll returnto this question in a moment. Likeeveryoneelse in 1787, Madison confronteda challenge for which historicalexperienceprovidedlittle guidance. Given that a large-scalerepresentativedemocracy had neverbeforeexistedin human history,his conjectures were probablyas well founded as they could possiblyhave been. Yetthe constitutionalsystem that Madison and his colwouldswiftlychangein response hadhelpedto create leagues to the powerful democraticimpulses that soon emerged. Madison himself helped to strengthen these democratic impulses and their impact. For the three decadesafterthe convention,he wasdeeplyimmersedin politicallife. Elected in 1789, he quickly to the new House of Representatives assumeda majorleadershiprole.Whateverhis reservations may have been, he introducedand quicklygained the passageofthe Billof Rights.In 1788, shortlyafterretiringfrom the House, he wrotethe VirginiaResolutions,attackingthe Alien and SeditionActs,and the followingyear,afterreturning to the Virginia House of Delegates, he defended the of state,where Resolutions.In 1801 he was made secretary tenure. On Jefferson's he remainedthroughoutJefferson's in 1808, he waselectedpresident,ashe wasagain retirement he sucin 1812. Tenyearsafterretiringfromthe presidency ceededJeffersonas rectorof the Universityof Virginia. In 1829 he was a delegateto the VirginiaConstitutionalConvention. During his final yearshe staunchlyopposed nullification and defended the union. He died in 1836 at the age of eighty-five. Madison's experience from 1790 onward led him, I believe, to develop somewhatgreatertrust in majoritiesmajorities consisting, of course, exclusively of white males-and a greater distrust of minorities that, in his view, threatenedthe interestsof the majority.Put simply, Madison, I believe, rapidly moved toward answers that were different from, or at least had a much different emphasisthan, those he presentedat the convention and in the Federalist. Madison increasinglyemphasized four propositions: 1. The greatest threat in the new American republic came from a minority,not the majority.(By majority I'll continue to mean a majorityof white male citizens.) September 2005 I Vol. 3/No. 3 443

or Democrat? Articles I James Madison: Republican

2. To protect their rights, liberties, and entitlements from minority factions, a majorityneeded to organize a political party. 3. To ensure that majoritieswould not threatenproperty rights, it was necessary(and perhapssufficient) that a majority of citizens owned property. As property owners, they would have an interest in protecting-not invading-the rights of property. 4. In the end, in a democraticrepublic,majoritiesmust be allowed to prevail. I want to illustrateMadison'schangein views by noting developmentsbearverybrieflysome well-knownhistorical these new on each of propositions. Like his close ally ing Madison Jefferson, swiftly concluded that representatives of the Federalist Partywere supportingand even achieving harmful to the interestsof a majorityof citizens. policies These included the pernicious Alien and Sedition Acts, the assumptionof state debts, Hamilton'ssuccessfuleffort to establisha nationalbank, and his supportfor Britainin its conflicts with France. It became obvious that to be effective the opposition MadThus Jefferson, neededits own politicalorganization. ison, and other like-minded opponents of the Federalists which soon came to be called createdthe RepublicanParty, with Andrew and finally, the Democratic-Republican Party, Jackson, simply the Democratic Party.Like virtually all advocatesof democracy,Madison had come to see, as he put it much later, that "no free Country has ever been without parties, which are a natural offspring of Freea dom."26Creatinga political party,however,represented kind is a For a Federalist from 10. political party step away of faction, a faction that is organizedby party leadersto win votes in elections. The word party itself, as Giovanni Sartoriemphasizedsome yearsago, derivesfrom the Latin verb meaningto divide.Though partywas sometimesseen the two termswere often as less derogatorythan "faction," A party is but a "partof a political used interchangeably. society,"not the whole.27In effect, then, organizedpolitical partiescompeting againstone anotherin elections are important elements of the solution to the twin problems of faction and the defense of majorityinterests.28 But competition between political parties would not diminish, and might even intensify,the danger necessarily to property rights if the suffragewere extended to those without substantial property,particularlythose without landed property-in Madison'sterms, "non freeholders." That dangerwould be reduced, of course, if most members of the electorateowned or expected to own property, and thus had an interest in protecting property rights. Though a solution along these lines was difficult, if not impossible in, say, Britain, in America the availabilityof land to the west provided a solution-to be sure, at the expense of the indigenous population. A westwardmovement that Madison had perhaps not clearly foreseen in 444 Perspectives on Politics 1787 was rapidlyresultingin a large population of indeownersthemselves, would who, asproperty pendentfarmers have little interestin threateningpropertyrights. Although Madison'slater views were hardly those of a passionate supporter of universal suffrage and political equality, a note he wrote in 1821 begins with the comment that his "observations in 1787 do not convey the speaker's[that is, Madison's]more full & maturedview" of the right to suffrage,which is "afundamentalArticle in RepublicanConstitutions."After consideringthe alternatives, he concluded that extending the suffrageto those without (landed) propertywas preferable,on grounds of feasibilityand justice, to any more restrictivealternative. "In a just & a free, Government," he wrote, ... the rights both of property& personsought to be effectually guarded. Will the latter be so in case of a universal & equal suffrage?.... Confining the right of suffrageto freeholders. .violates the vital principleof free Govt. that those who are to be bound by the laws, ought to have a voice in making them." After examining four alternative that would deprive or limit the suffrageof arrangements those without property,Madison concluded:

that the Undereveryview of the subject,it seemsindispensable Mass of Citizensshould not be without a voice.... and if the be betweenan equal & universalright of sufonly alternative fragefor each branchof Govt. and a confinementof the entire right to part of the Citizens,it is better that those having the & personsboth, interestat stakenamelythatof property greater should be deprivedof half their sharein the Govt.; than those havingthe lesserinterest,that of personalrightsonly,shouldbe of the whole.29 deprived

Political equality means that the majority must be allowed to prevail. Although Madison may never have fully overcome his worries about the potential threatsto propertyrightsarisingfrom voterswith little or no landed property,as he observedthe expansion in propertyownershipamong his fellow citizens,he seems to have become somewhat more committed to the fundamentalprinciple of majorityrule. Toward the end of his life, particularlyafter John C. Calhoun had begun his attackson the principleof majority rule, Madison'sdefense of the principle was forceful and unambiguous. In a letter written in 1833, Madison contended:

[W]hatever opinions may be formedon the generalsubjectof of our own, everyfriend or the interpretation confederal systems, to Republican Government ought to raisehis voice againstthe sweepingdenunciationof majorityGovernmentsas the most of all Governments .... and intolerable tyrannical [T]hegeneral governquestionmustbe betweena republican ment in which the majorityrule the minority,and a Government in which a lesser numberor the least number rule the altoGovernments majority.... Those who denouncemajority getherbecausethey mayhavean interestin abusingtheirpower, denounce at the time all RepublicanGovernmentand must

diversities in Sweden, its extraordinary homogeneity enabled Swedes to negotiate national policies with a very high degree of consensus in the cabinet, the parliament, on 'MajorityGovernThat sameyearin a "Memorandum and the entire country.38 At the other extreme, consider ment,"' he wrote: the difficultiesthe EuropeanUnion now faces in creating a constitution, given the diverseand conflicting interests, of If majority be the worst Governments those ... governments bewithin thepaleof therepublican views, values, and political culturesthat continue to exist whothink andsaysocannot of aristocracy, faith. Theymusteither jointheavowed disciples Europeans. a perfect among ormonarchy, orlookfora Utopia exhibiting oligarchy It is difficult, even impossible, to reconcile Madison's of interests, and feelings nowhere opinions homogeneousness seeming optimism about the beneficialaffectsof size with communities.31 yet foundin civilized his clear recognition of the crucial differencein interests I find it regrettable that Madison is almost entirelyknown among propertyownersin differentstatesstemming"from for his 1787 constitutional theory, for there can be little (the effects of) their having or not having slaves."Didn't doubt that as he and the American political system both the framers make the Civil War virtually inevitable by into the union the Southernstateswith econevolved, he revisedhis views in ways that were far more incorporating social YetevenMadison's democratic. revised constitutional omies, theory systems, and cultures based on slavery? Whether separationratherthan union would have been contained at least three serious flaws. The firstis his argumentin the Federalist that increased more desirablein the long run is a question too complex to examine here. My point simply is that enlarging the size reduces the dangers of factionalism.At the convention itself he had-rightly, I believe-"contended that the sphere might just set the stage for irresolubleconflict. I have sometimes wondered whether Madison stressed States were divided into different interests not by their differencesin size, but by other circumstances;the most the advantages of size in orderto counter the objectionsof materialof which resultedpartly from climate, but printhe Anti-Federalists, perhapsthe most vigorousopponents If so, it was a shrewdmove. But from effects their or not of the new federal (the of) system. cipally having having slaves. These two causes concurred in forming the great that does not make his conjectureempiricallyvalid. in Madison's division of interestsin the U. States."32 The secondmajorflawthatremained revised His much betterknown argumentin the Federalist constitutional is the from tacit exclusion full cititheory (espein and well have been as a of 10 useful an enormous share of the adult Like 51) cially essays may zenship population. rhetoricalpoint that would help to reducefearsexpressed other men of his time, Madison seems to have taken for at the convention, and outside the convention by Antigrantedthat suffrageshould be restrictedto men, and that in that the interests of the small states therewas no question of the right to vote, as well as many Federalists, people would suffer in the proposed federalsystem.33But if we other fundamentalrights,being extendedto women. And consider the latter argument as an empiricalproposition while women had few rightsas citizens,slaveshad no rights in political science, two comments seem to me justified.It at all. LikeWashington,Jefferson, and manyothereminent could not possibly have been tested adequatelyin his own Virginians,Madisonowned slaves,which he had inherited time. And two centuries of experience since then flatly fromhis father.LikeWashingtonandJefferson, he believed contradicthis proposition. that slaverywas an evil,39 and he seems to have treated democraciesof our time, the Among the representative humanely those he possessed.Like his fellow Virginians, smaller countries are no more vulnerableto faction than however,he chose not to freehis slavesduringhis own lifethe larger ones: consider the three Scandinaviancountime or to contest the institution publicly.40Nor did he tries, together with Finland, the Netherlands, Switzer- follow Washington's exampleand emancipatethem at his death. Instead, no doubt fearing his wife's impoverishland, and New Zealand. Or consider that among the LikeJefferson, he supported seventy or so countries of the world that meet today's ment, he willed them to her.41 standardsfor democracy-rather higherstandards,by the schemesof gradualemancipation"andthe colonizationof freedmenin Africaor some other remote region."In 1819 way, than Madison's-countries with populationsunder a million are much more prevalentthan largercountries.34 he evenproposedthatmoneyobtainedfromthe saleofwestOr if we move to a much smallerscale,an analysisof town ern lands be used to purchaseenslavedpersonsfrom their in Vermont reveals a remarkable combination of masters-after which they would be shipped to Africa.42 meetings and for the direct Of course,the schemewent nowhere. vigor, civility, participation, respect the smaller the the more these The third major flaw in his post-1787 constitutional town, democracy.Indeed, tend to qualities appear.35 theory had been mainly overlooked by biographers,hisMadison was right in thinking that diversitytends to torians,politicalscientists,and constitutionallawyersuntil increasewith size.36But he overlooked the costs of hetGarry Wills called it forcefully to our attention.43This the and of For examwas the infamous two-fifths rule, accordingto which, in erogeneity advantages homogeneity.37 until created new cultural the words of Section 3, Article I: "Representatives and ple, immigration recently September 2005 1Vot.3/No. 3 445

wouldfeellessof thebias thatminority maintain governments or theseductions of power.30 of interest

Articles I James Madison: or Democrat? Republican

directTaxesshall be apportionedamong the severalstates .. accordingto their respectiveNumbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons .... three fifths of all other Persons."Who were these "other Persons"? Slaves, of course.44Wills argues, I that the extra seats in the House-and rightly, believe, thereforein the electoral college-had, in Wills's words, "agreat deal to do with the fact that for over half a century, right up to the Civil War, the management of the government was disproportionately controlled by the South."45 It even "undermined the verypossibilityof debating or changing the status of slaves-as the gag rules of the 1830s and 1840s would demonstrate."46 Although Madison seems not to have played a big part in the adoption of this constitutionalprovision,he supportedit at the convention and throughout his life. Madison was limited in important ways by his time and place, yet he helped to launch the world'sfirst experiment in what would later come to be called representative democracy.The political institutions, practices,and ideas about populargovernmentto which he contributed contained dynamic-even revolutionary-elements that, once set in motion, would continue to evolve, sometimes quite rapidly. Madison was a part of that evolution. In his 1787 constitutional theory, a fear of majoritiesrequiredthat barriers to their power be imposed by constitutionaland other means. In his post-1787 theory,he came to defend majorities. Yet many of the crucial elements of the constitutional system that reflected his earlier,and not his later, views have remainedin place to the presentday. I sometimes wonder what further revisions Madison would make in his constitutional theory if he were alive today. I'm inclined to think that after he had reflectedat length on the changes since his time in democraticideas and practices,both in his own country and elsewhere,he might well prove to be a vigorous contemporarycritic of the Constitution he helped so much to create. preted as an expansionof views he actuallyheld earlierbut had suppressedin his public rhetoric. Federalist 10 (Hamilton, Jay,and Madison 2000, 58-59). In the words of a leading historian, they were "constitutional oligarchies" (Martines 1979, 148). Adams 1980, 99-117. Speakingat the Pennsylvania ratifyingconvention in November 1787, a mere two months after the convention ended, JamesWilson, who was Madison's ally at the Convention and, like Madison, one of its most influentialmembers remarked: "... [T]he three species of simple governments.... are the and democratical.In a monarchical,aristocratical the monarchy, supremepower is vested in a single person;in an aristocracy.... by a body formed upon the principle of representation,but enjoying their station by descent, or election among themselves, or in right of some personalor territorial qualifications;and lastly,in a democracy,it is inherent in a people, and is exercisedby themselvesor by their representatives.... [O]fwhat descriptionis the Constitution before us? In its principles,Sir, it is purely democratical: varyingindeed in its form in order to admit all the advantages,and to excluded all the disadvantages which are incidental to the known and establishedconstitutions of government. But when we take an extensiveand accurateview of the streamsof power that appearthrough this great and comprehensiveplan ... we shall be able to trace them to one great noble source,THE PEOPLE. [sic]" (Bailyn 1993, 802-3, emphasisadded). The following June, at the Virginia ratifyingconstitution, respondingto the criticismsof PatrickHenry,John Marshallcontended that "The Constitution provided for 'a well regulateddemocracy,'where no king, or president,could undermine representative government"(Simon 2002, 25). An interestingdeviation from this patternpersisted in presidentialinauguraladdresses.I find that throughout the nineteenth century,if a president referredto the Americanpolitical system in an inaugural address,he used the terms republicor republican and, with only one exception, never democracy or democratic.The exception was the ill-fatedWilliam Henry Harrisonwho in 1841 said of the Framers that "therewere in it [the Constitution] features which appearednot to be in harmonywith their ideas of a simple representative democracyor republic." From this we can infer that the terms "republic" were understood and "representative democracy" as equivalent.I need hardlyadd that during the twentieth century,in their inauguraladdressespresidents frequentlyreferredto the United States as democraticor a democracy.In his four inaugural

7 8 9 10

11

Notes

1 Dahl 1956. 2 The extent to which Madison expressedhis real is a matter of some disagreeviews in the Federalist ment. See note 7, below. 3 Ellis 2001, 53. 4 Miller 1992, 15. 5 Padover1953, 22. 6 Samuel Kernell (2003) arguesthat "theMadisonian model was formulatedafter the fact, specificallyin Federalist 51 and its companion essays,in order to the Constitutions ratification" (p. 93). If promote his interpretationis correct, then Madison'sfirst constitutional theory was simply "campaignrhetoric" (p. 114), and his laterviews might be inter446 Perspectives on Politics

12

13

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

23

24 25 26 27

28

addresses,FDR used these terms twenty times and not once. Reaganand the first Bush used "republic" both in equal numbers,while Clinton and the second Bush employed only the term "democracy" in their inauguraladdresses. In Europe, as the OxfordEnglishDictionaryreminds came to mean "withouta monarch," us, "republic" as in France,Germany,and elsewhere.Thus the Scandinaviancountries, along with Holland and Spain, are not republics;but, as in the rest of the world, their people rightly call them democracies. An authoritativeexample:The OxfordEnglishDictionarydefines democracyas "governmentby the people; that form of governmentin which the sovereign power residesin the people as a whole, and is exercisedeither directlyby them (as in the small republicsof antiquity) or by officerselected by them." Matthews 1995, 81. Miller 1992, 53 f. Damasio 1995. Federalist 10 (Hamilton, Jay,and Madison 2000, 59). Ibid., 54-56 (emphasisadded). Ibid., 57. Padover1953, 254. Richard 1994. Padover1953, 254. At the Virginia RatifyingConvention in June, 1788, PatrickHenry gave a lengthy and passionatecriticism of the Constitution for, among other things, its omission of a Bill of Rights that would protect the freedom of religion, trial by jury, and "theother great rights of mankind"that were, he noted, preservedby "ourown Constitution" (i.e., the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia). In his reply,Madison argued, "If there were a majorityof one sect, a Bill of Rights would be a poor protection for liberty.Happily for the States, they enjoy the utmost freedom of religion. This freedom arisesfrom a multiplicity of sects, which pervadesAmerica, and which is the best and only securityfor religiousliberty in any society" (Bailyn 1993, 678, 690). I am gratefulto RichardMatthews for calling my attention to the first two of these. In If Men Were Angels,he providesan excellent account of Madison's views on these and other important constitutional issues. Federalist 10 (Hamilton, Jay,and Madison 2000, 61). Ibid. (Hamilton, Jay,and Madison 2000, 64). Farrand1987, 3:452, appendixA. Sartori(1976, 5 f.), providesan excellent account of the evolution of the term "party" and its distinction from "faction." For a carefullypresentedview of the evolution of Madison's viewson parties, seeRiemer1968,173-74.

29 Farrand1987, 3:450-55, appendixA, punctuation as in original. His continuing concerns for property are revealedby his unwillingnessto rejectone alternative: "Confiningthe right of electing one Branch of the Legislature to freeholders,and admitting all others to a common right with holders of property, in electing the other branch."He points out that this had been tried and abandonedin New Yorkbut "is still on trial in N. Carolina ... It is certain that the trial, to be satisfactoryought to be continued for no inconsiderableperiod; untill [sic] in fact the nonfreeholdersshould be a majority"(p. 454). 30 Madison, Writings, 9:520-28, cited in Meyers 1973, 525. 31 Madison, Writings, 9:526, cited in Riemer 1968, 157. 32 Farrand1987, 1:486. 33 This is clearlythe case in his responseto the (ultimately successful)insistenceby delegatesof the small states on equal representation in the Senates. Three large states-Virginia, Massachusetts,and Pennsylvania-were, he argued,deeply divided by their differentinterests.For example, in "staple productionsthey were as dissimilaras any three other Statesin the Union" (Ibid., 447). 34 Diamond 2002, 26, table 1. 35 Bryan2004, 69-81, 136, 231, 296-97. See also Bryanand McClaughry 1989. 36 For evidence and discussion, see Dahl and Tufte 1973, 91ff. 37 Alesina and Spolaore(2003) propose that "thesizes of national states (or countries) are due to the tradeoffs between the benefits of size and the costs of heterogeneityof preferencesover public goods and preferencesprovidedby government.... Our main argument [is] that democratization,tradeliberalization, and reductionof warfareare associatedwith the formation of small countries,whereashistorically the collapse of free trade, dictatorships,and wars are associatedwith large countries"(pp. 6, 15). 38 Lewin 1988, 195-206. 39 Rakove 1996, 337. Ralph Ketcham (1990) writes: "Though brought up among slavesand dependent on their labor,he abhorredthe institution of slavery and sought to have as little as possible to do with it" (p. 148). 40 An exception was one Billey. "In 1783, as Madison preparedto returnto Virginia from Philadelphia,he discoveredthat, after nearlyfour yearsin the company of free servants,Billey was 'too thoroughly tainted to be fit companion for fellow slavesin Virginia.' . . . Why, Madison asked his father,should Billey be punished 'merelyfor coveting the liberty for which we have paid the price of so much blood, and have proclaimedso often to be right, and September 2005 i Vol. 3/No. 3 447

Articles | James Madison: or Democrat? Republican

worthy the pursuit, of every human being"' (Ketcham 1990, 148). All of Madison'spronouncements about the evils of slaveryare in privateletters or documents. "[I]n his will Madison said of his slavesmerely that none of them should be sold without the slave's consent as well as Dolley Madison's.A lifetime of opposition to slaveryhad thus been reducedin Madison'swill to a gesture,likely to be ineffectual, not of freedom, but only of decent treatment.As happened again and again in slave states, the demands of creditorsand estate legateessubverted Madison'sintentions" (Ketcham 1990, 629). Meyers 1973, 398; Ketcham 1990, 625-29. Wills 2003. When Madison discussedthe conflict of interests between propertyownersin free and slavestates earlyin the Convention, he had proposedthat instead of the two-fifths rule, slaves"shouldbe represented in one branchaccordingto the number of free inhabitants only; and in the other accordingto the whole no. counting the slaves as (if) free. By this arrangement the SouthernScale (sic-States?) would have the advantagein the House, and the Northern in the other. He had been restrained from proposingthis two considerations: one was his unwillexpedient by to of interests on an occaingness urgeany diversity sion when it is but too apt to ariseof itself-the other was the inequalityof powersthat must be vested in the two branches,and which wd. destroythe equilibrium of interests" (Farrand1987, 1:486-87). Wills 2003, 6. Ibid., 4. Dahl, RobertA., and EdwardTufte. 1973. Size and Stanford:StanfordUniversityPress. democracy. error: Damasio, Antonio. 1995. Descartes' Emotion, reason,and the human brain.New York:Avon Books. Diamond, Larry.2002. Thinking about hybrid regimes. Journalof Democracy (April):21-50. The revolutionary Ellis, Joseph. 2001. Foundingbrothers: New York: Alfred A. generation. Knopf. Farrand, Max, comp. 1987. Records ofthe federal convention of 1787. Rev. ed. 4 vols. Ed. James H. Hutson. New Haven: YaleUniversityPress. Hamilton, Alexander,John Jay,and JamesMadison. 2000. TheFederalist. New York:Modern Library. (Orig. pub. 1787.) Kernell,Samuel. 2003. "The true principlesof republican government": JamesMadison'spolitiReassessing cal science. In JamesMadison:Thetheoryand practice ed. Samuel Kernell,92-125. of republican government, Stanford:StanfordUniversityPress. Ketcham, Ralph. 1990. JamesMadison:A biography. Charlottesville: UniversityPressof Virginia. and consensus democLewin, Leif. 1988. Majoritarian The Swedish racy: experience.ScandinavianPolitical Studies21 (3): 195-206. Martines, Lauro. 1979. Powerand imagination:City statesin Renaissance Italy.New York:AlfredA. Knopf. Matthews, RichardK. 1995 If men wereangels: James Madisonand the heartless Lawrence: empireof reason. UniversityPressof Kansas. Meyers,Marvin, ed. 1973. The mind ofthefounder: Sources of thepolitical thoughtofJamesMadison.Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. Miller,William Lee. 1992. The business ofMay next: JamesMadisonand thefounding. Charlottesville: UniversityPressof Virginia. Padover,Saul K., ed. 1953. TheforgingofAmerican Selected federalism: writingsofJamesMadison.New York:HarperTorchbooks. Politicsand Rakove,JackN. 1996. Originalmeanings: ideasin the makingof the Constitution. New York: AlfredA. Knopf. Richard,CarlJ. 1994. Thefoundersand the classics: CamGreece, Rome,and theAmericanEnlightenment. Harvard Press. bridge: University Riemer,Neal. 1968. JamesMadison.New York:Washington SquarePress. A Sartori,Giovanni. 1976. Partiesandparty systems: Uniframeworkforanalysis.Cambridge:Cambridge versity Press. Simon, James F 2002. Whatkind of nation?Thomas to createa John Marshall,and the epicstruggle Jefferson, UnitedStates.New York:Simon and Schuster. Wills, Garry.2003. "Negro Jefersonand the president": slavepower.Boston: Houghton Miffin.

41

42 43 44

45 46

References

constituAdams, Willi Paul. 1980. ThefirstAmerican tions:Republican and the ideology makingof state constitutions in the Revolutionary era.Chapel Hill: Universityof North CarolinaPress. Alesina, Alberto, and Enrico Spolaore.2003. Thesize of nations.Cambridge:MIT Press. Bailyn, Bernard,ed. 1993. The debateon the Constituand Antifederalist tion, Federalist articles,and speeches, lettersduringthe struggle overratification. New York: Libraryof America. TheNew England Bryan, Frank.2004. Realdemocracy: town meetingand how it works.Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press. Bryan, Frank,and John McClaughry.1989. The Vermontpapers:Recreating on a human scale. democracy Chelsea, VT: Chelsea Green PublishingCo. Dahl, RobertA. 1956. A prefaceto democratic theory. Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press. 448 Perspectives on Politics

También podría gustarte

- The Framers' Intentions: The Myth of the Nonpartisan ConstitutionDe EverandThe Framers' Intentions: The Myth of the Nonpartisan ConstitutionAún no hay calificaciones

- Presidents Above Party: The First American Presidency, 1789-1829De EverandPresidents Above Party: The First American Presidency, 1789-1829Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (2)

- Not All Conservatives Are ConstitutionalistDocumento48 páginasNot All Conservatives Are ConstitutionalistTomAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist 78 ThesisDocumento5 páginasFederalist 78 Thesisjosephineromeroalbuquerque100% (2)

- James Madison: The Federalist PapersDocumento57 páginasJames Madison: The Federalist PapersDivinekid082Aún no hay calificaciones

- James Madison Federalist 10 ThesisDocumento4 páginasJames Madison Federalist 10 ThesisEssayHelpEugene100% (2)

- Research Paper On James MadisonDocumento6 páginasResearch Paper On James Madisonc9rz4vrm100% (1)

- Federalist Paper 10 Madisons ThesisDocumento6 páginasFederalist Paper 10 Madisons ThesiselaineakefortwayneAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist Paper 10 What Is Madisons ThesisDocumento8 páginasFederalist Paper 10 What Is Madisons Thesisafjrqxflw100% (1)

- Political Cocaine: How America Got Hooked On the Two Party System and How to InterveneDe EverandPolitical Cocaine: How America Got Hooked On the Two Party System and How to InterveneAún no hay calificaciones

- Jillson - The Political Structure of Constitution Making The Federal Convention of 1787Documento25 páginasJillson - The Political Structure of Constitution Making The Federal Convention of 1787Bart SipsAún no hay calificaciones

- Confronting the Politics of Gridlock, Revisiting the Founding Visions in Search of SolutionsDe EverandConfronting the Politics of Gridlock, Revisiting the Founding Visions in Search of SolutionsAún no hay calificaciones

- A Concise History of American Politics: U S Political Science up to the 21St CenturyDe EverandA Concise History of American Politics: U S Political Science up to the 21St CenturyAún no hay calificaciones

- Jefferson, Madison, and the Making of the ConstitutionDe EverandJefferson, Madison, and the Making of the ConstitutionCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (1)

- The Right to Nominate: Restoring the Power of the People over the Power of the PartiesDe EverandThe Right to Nominate: Restoring the Power of the People over the Power of the PartiesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Boss and the Machine: A Chronicle of the Politicians and Party OrganizationDe EverandThe Boss and the Machine: A Chronicle of the Politicians and Party OrganizationAún no hay calificaciones

- Progressivism: The Strange History of a Radical IdeaDe EverandProgressivism: The Strange History of a Radical IdeaCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (4)

- Chapter 2Documento11 páginasChapter 2mmbdsjhvsmAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist 10 Brutus 1 Analytical ReadingDocumento4 páginasFederalist 10 Brutus 1 Analytical ReadingKe'Mara DavisAún no hay calificaciones

- When at Times the Mob Is Swayed: A Citizen’s Guide to Defending Our RepublicDe EverandWhen at Times the Mob Is Swayed: A Citizen’s Guide to Defending Our RepublicAún no hay calificaciones

- The Centrist Solution: How We Made Government Work and Can Make It Work AgainDe EverandThe Centrist Solution: How We Made Government Work and Can Make It Work AgainAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Madisons Thesis in Federalist No 10Documento5 páginasWhat Is Madisons Thesis in Federalist No 10Lisa Garcia100% (2)

- Federalist 10 SummaryDocumento3 páginasFederalist 10 SummarylcjenleeAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist Paper 10 ThesisDocumento7 páginasFederalist Paper 10 Thesissugarmurillostamford100% (2)

- Schudson, M. The Public Sphere and Its Problems. Bringing The State (Back) in PDFDocumento19 páginasSchudson, M. The Public Sphere and Its Problems. Bringing The State (Back) in PDFIsaac Toro TeutschAún no hay calificaciones

- We the Elites: Why the US Constitution Serves the FewDe EverandWe the Elites: Why the US Constitution Serves the FewAún no hay calificaciones

- Reconstructing the Commercial Republic: Constitutional Design after MadisonDe EverandReconstructing the Commercial Republic: Constitutional Design after MadisonCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2)

- 14 Federalist 10 QuestionsDocumento3 páginas14 Federalist 10 Questionsvaani ghaiAún no hay calificaciones

- We the People: The Strategy to Convene a Convention – For Republic ReviewDe EverandWe the People: The Strategy to Convene a Convention – For Republic ReviewAún no hay calificaciones

- Patriotic ProjectDocumento9 páginasPatriotic Projectb8kf9js6c2Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Defense of Party Spirit: ArticlesDocumento15 páginasA Defense of Party Spirit: ArticlesChrissy HarrisAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist 10 What Is Madisons ThesisDocumento5 páginasFederalist 10 What Is Madisons Thesiskatherinealexanderminneapolis100% (2)

- Federalist Paper 51 ThesisDocumento5 páginasFederalist Paper 51 Thesiskimberlyreyessterlingheights100% (2)

- Unmasking the Administrative State: The Crisis of American Politics in the Twenty-First CenturyDe EverandUnmasking the Administrative State: The Crisis of American Politics in the Twenty-First CenturyCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- The Struggle to Limit Government: A Modern Political HistoryDe EverandThe Struggle to Limit Government: A Modern Political HistoryAún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist No. 10 ThesisDocumento6 páginasFederalist No. 10 Thesisjennyschicklingaurora100% (2)

- Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the PeopleDe EverandOur Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the PeopleCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (7)

- American Statesmanship: Principles and Practice of LeadershipDe EverandAmerican Statesmanship: Principles and Practice of LeadershipJoseph R. FornieriAún no hay calificaciones

- Between Authority and Liberty: State Constitution-making in Revolutionary AmericaDe EverandBetween Authority and Liberty: State Constitution-making in Revolutionary AmericaCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2)

- No Parties Here: Benjamin FranklinDocumento4 páginasNo Parties Here: Benjamin FranklinHimanshu TaramAún no hay calificaciones

- The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized EraDe EverandThe Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized EraAún no hay calificaciones

- 8 - Tci 8 4 Reading and Comp QuestionsDocumento4 páginas8 - Tci 8 4 Reading and Comp Questionsapi-242867432Aún no hay calificaciones

- What the Anti-Federalists Were For: The Political Thought of the Opponents of the ConstitutionDe EverandWhat the Anti-Federalists Were For: The Political Thought of the Opponents of the ConstitutionCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (10)

- When Money Talks: The High Price of "Free" Speech and the Selling of DemocracyDe EverandWhen Money Talks: The High Price of "Free" Speech and the Selling of DemocracyAún no hay calificaciones

- The American View of Freedom: What We Say,: Whatwe MeanDocumento9 páginasThe American View of Freedom: What We Say,: Whatwe MeanGennaro ScalaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ron DeSantis in Office: An Unauthorized Account of the Florida Republican's Efforts to Uphold the Constitution as a Congressman and GovernorDe EverandRon DeSantis in Office: An Unauthorized Account of the Florida Republican's Efforts to Uphold the Constitution as a Congressman and GovernorAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 1Documento15 páginasChapter 1mmbdsjhvsmAún no hay calificaciones

- GUNNELL, John G. The Genealogy of American PluralismDocumento14 páginasGUNNELL, John G. The Genealogy of American PluralismVinicius FerreiraAún no hay calificaciones

- A Necessary Evil: A History of American Distrust of GovernmentDe EverandA Necessary Evil: A History of American Distrust of GovernmentCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (25)

- Smith ReasonPassionPolitical 1960Documento21 páginasSmith ReasonPassionPolitical 1960syminkov8016Aún no hay calificaciones

- Federalist 57Documento3 páginasFederalist 57maghribiaAún no hay calificaciones

- SBFS RNFDocumento23 páginasSBFS RNFCyrus Adrian RomAún no hay calificaciones

- UCSP Lecture NotesDocumento2 páginasUCSP Lecture NotesDeona Faye PantasAún no hay calificaciones

- ContempoDocumento3 páginasContempoJan Eric Lansang100% (3)

- Human Right Mahatma Gandhi University BBA CBCS 5-1Documento19 páginasHuman Right Mahatma Gandhi University BBA CBCS 5-1Rajesh MgAún no hay calificaciones

- Political CultureDocumento28 páginasPolitical CultureCBSE UGC NET EXAMAún no hay calificaciones

- Vietnamese Studies in South Korea: Development and Trend: LEE Han WooDocumento15 páginasVietnamese Studies in South Korea: Development and Trend: LEE Han WooTrinh DươngAún no hay calificaciones

- Dictablanda Edited by Paul Gillingham & Benjamin T. SmithDocumento62 páginasDictablanda Edited by Paul Gillingham & Benjamin T. SmithDuke University PressAún no hay calificaciones

- Balibar, World Borders, Political BordersDocumento9 páginasBalibar, World Borders, Political BordersAndrea TorranoAún no hay calificaciones

- M.A. Political Science - 2016Documento21 páginasM.A. Political Science - 2016Vikshit Jaat Jaat7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Political Science As Master ScienceDocumento11 páginasPolitical Science As Master Sciencetarun chhapola67% (3)

- Power and The Three Faces of Power: MR Jay Mhar Z. Gaffud Philippine Politics and GovernanceDocumento36 páginasPower and The Three Faces of Power: MR Jay Mhar Z. Gaffud Philippine Politics and GovernanceJoeyboy MateoAún no hay calificaciones

- Politics Is A Process by Which Groups of People MakeDocumento2 páginasPolitics Is A Process by Which Groups of People MakemafelcAún no hay calificaciones

- State of NatureDocumento53 páginasState of NatureAndrés Cisneros SolariAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is The Difference Between Socialism and Communism?Documento2 páginasWhat Is The Difference Between Socialism and Communism?Muhammad AhmadAún no hay calificaciones

- (MOOT 2019) International Law Relevant ConceptsDocumento6 páginas(MOOT 2019) International Law Relevant ConceptsDILG STA MARIAAún no hay calificaciones

- ADocumento6 páginasAMOHD SABREEAún no hay calificaciones

- LLB Study Planner 2019 CommencingDocumento2 páginasLLB Study Planner 2019 Commencingchloedeilly123Aún no hay calificaciones

- POSC 1013 Lesson 1Documento4 páginasPOSC 1013 Lesson 1bhettyna noayAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethiopian Constitutional Law (ABOUT LAW)Documento664 páginasEthiopian Constitutional Law (ABOUT LAW)Tensae B. Negussu H.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Homo Sacer vs. Homo Soccer Mom-Halit MustafaDocumento30 páginasHomo Sacer vs. Homo Soccer Mom-Halit MustafaJorge RodríguezAún no hay calificaciones

- QUIJANO 1989 Paradoxes of Modernity in Latin AmericaDocumento32 páginasQUIJANO 1989 Paradoxes of Modernity in Latin AmericaLucas Castiglioni100% (1)

- Political Science Unit 1Documento4 páginasPolitical Science Unit 1Vishal Singh ChauhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Human Rights and Crimes Against HumanityDocumento3 páginasHuman Rights and Crimes Against HumanityAsuderaziye GülmezAún no hay calificaciones

- Case: Macariola Vs AsuncionDocumento18 páginasCase: Macariola Vs Asuncionjica GulaAún no hay calificaciones

- Theory of DecentralizationDocumento36 páginasTheory of DecentralizationIqbal SugitaAún no hay calificaciones

- Is The Philippines A State or A NationDocumento2 páginasIs The Philippines A State or A NationHeherson Custodio78% (9)

- Essay On Human Rights AspectDocumento3 páginasEssay On Human Rights Aspectgirlee manlaviAún no hay calificaciones

- 2008.consti 1 Lecture With CasesDocumento132 páginas2008.consti 1 Lecture With CasesRey LacadenAún no hay calificaciones

- Administrative Discretion - Definition, Scope and Constitutional AspectDocumento14 páginasAdministrative Discretion - Definition, Scope and Constitutional AspectHumanyu KabeerAún no hay calificaciones

- Alex Brillantes Jr.Documento69 páginasAlex Brillantes Jr.anon_531265714Aún no hay calificaciones