Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

In Re RJR Nabisco Inc.

Cargado por

viva_33Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

In Re RJR Nabisco Inc.

Cargado por

viva_33Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

In Re RJR Nabisco Inc. Shareholders Litigation No.

10,389 Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware, New Castle January 31, 1989 Facts: Pending was a motion to intervene as defendants and to assert a declaratory judgment counterclaim. Applicants were Lazard Freres & Company and Dillon Read & Company, Inc., the investment bank advisors to the special committee of the board of directors of RJR Nabisco, Inc. in the auction and sale of that company to an affiliate of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. ("KKR"). Also pending was a motion by plaintiffs, RJR shareholders prior to the KKR merger, to stay this litigation while a subsequently filed class suit by these plaintiffs charging the investment banks with negligence moves forward in the Supreme Court of the State of New York. The pending action was brought on October 20, 1988 as a class action on behalf of RJR Nabisco's public common shareholders. Defendants were RJR, the directors of RJR at the time of the auction, and KKR and its affiliates. The theory of the amended complaint, in brief, was that in conducting an auction sale of the Company, the directors breached the fiduciary duties of care and loyalty that they owed in such circumstances to the corporation and its shareholders. The amended complaint also claimed that KKR participated in or aided that breach. The applicants, who advised the special committee of directors that managed the sale process, were not made defendants in this suit, although extensive discovery was made in connection with plaintiffs' application for a preliminary injunction. On January 31, 1989, plaintiffs' application for a preliminary injunction enjoining the consummation of KKR's tender offer for RJR's stock was denied. On February 28, 1989, the same plaintiffs filed suit against Lazard and Dillon in the Supreme Court of the State of New York alleging that the investment banks were negligent in conducting the auction and in valuing the bids of KKR and its competitor--a group involving management of the Company, Salomon Brothers Inc., and Shearson Lehman Hutton, Inc. This negligence was alleged to constitute a breach of duty running directly to the RJR shareholders and its alleged violation was said to have proximately caused injury to the class. Lazard and Dillon responded to the New York complaint on March 30, 1989 with a motion to dismiss or in the alternative to stay the action. The banks indicated in support of their request to stay the New York action that if the New York complaint was deemed to state a claim, the banks would submit to the jurisdiction of this court in which this earlier action against RJR, KKR and the individual directors had already moved forward. On August 16, 1989, Justice Pecora of the New York State Supreme Court denied the motion to dismiss. He did not address the motion to stay. That case was on

appeal before the New York State Supreme Court, Appellate Division--First Department. In the Delaware action, KKR, RJR, and the director defendants filed an answer and amended answer. The defendants alleged counterclaims seeking, among other things, a declaratory judgment that the special committee, "as advised by its advisors," acted properly in conducting the auction and accepting the KKR bid. On November 15, 1989, Lazard and Dillon filed their motion to intervene in the Delaware action pursuant to Chancery Court Rule 24. Issues: 1. Whether or not the court may properly assert personal jurisdiction over the plaintiffs with respect to the counterclaim that the applicants seek to assert?; 2. Whether the court has subject matter jurisdiction over that counterclaim?; 3. Whether assuming there was jurisdiction to adjudicate the proposed counterclaim, whether applicants had a right to litigate that claim in court? Held: 1. Yes 2. Yes 3. Yes Ratio: 1. This court had personal jurisdiction over the plaintiffs in this action for the purpose of litigating any claim arising from or substantially relating to the acts and transaction that they allege as the basis of their amended complaint. Inarguably, a court has personal jurisdiction over a plaintiff as to any counterclaim asserted by a defendant arising out of the facts alleged in the complaint. There is not the slightest reason to hold that a different result pertains when a party not originally joined, but who meets the test of Rule 24 asserts a counterclaim arising out of the same facts as those alleged in the complaint. In so concluding, in plaintiffs' favor, that the modern law of jurisdiction requires that minimum contacts between the defendant (by counterclaim) and the forum must exist before personal jurisdiction may effectively be asserted over that person. 2. The question of subject matter jurisdiction involves not the constitutional question of fairness that was implicated in the question of personal jurisdiction, but the Delaware specialty of carrying forward and applying in fresh fields the ancient distinctions generated by the law-equity split. In working in this particular area, Delaware judges bear a particular responsibility to assist in the evolution of a workable body of rules that permits our divided system to achieve efficiency, while maintaining the special utility that this ancient division offers in the late 20th Century world.

3. The question whether the class could assert a claim for damages cognizable in equity solely against one in contractual privity with its fiduciary. This court's subject matter jurisdiction over the proposed counterclaim is sound, even assuming that such an action could not be brought in Chancery originally. What distinguishes this case is the fact that an action against the fiduciary arising from the same transaction has been properly instituted in this court. Assuming that applicants possess a Rule 24(a) right to intervene as a defendant, it would be anomalous if there were no subject matter jurisdiction with respect to their counterclaim, which would be a mandatory counterclaim under Rule 13. The law of the federal courts which like this court, are courts of limited jurisdiction, establish that the District Court will have jurisdiction over a compulsory counterclaim asserted by Rule 24. Thus, this court has ancillary jurisdiction over the claims of every kind arising from the RJR acquisition transaction that could be asserted by the class against its fiduciaries and those who advised the fiduciaries. To hold otherwise is not compelled by statutes or decided cases and would contribute to a wooden and unproductive jurisprudence concerning the operation of dual jurisdiction court system. Thus, concluding that this court does have jurisdiction in both the personal and subject matter senses of the term to hear the proposed counterclaim, the analysis turns to Rule 24. As indicated, that analysis leads to the conclusion that while mandatory intervention would not be proper in this instance, permissive intervention would be authorized.

También podría gustarte

- VIB Case Study On RJR NabiscoDocumento1 páginaVIB Case Study On RJR NabiscoSatyajeet SenapatiAún no hay calificaciones

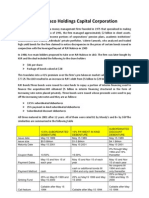

- The Relative Pricing of High-Yield Debt: The Case of RJR Nabisco Holdings Capital CorporationDocumento24 páginasThe Relative Pricing of High-Yield Debt: The Case of RJR Nabisco Holdings Capital CorporationAhsen Ali Siddiqui100% (1)

- Cases RJR Nabisco 90 & 91 - Assignment QuestionsDocumento1 páginaCases RJR Nabisco 90 & 91 - Assignment QuestionsBrunoPereiraAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study-Finance AssignmentDocumento12 páginasCase Study-Finance AssignmentMakshud ManikAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study: United Technologies Corp. and Raytheon Company Deal 1. What Is The Specific Function of A. The MergerDocumento15 páginasCase Study: United Technologies Corp. and Raytheon Company Deal 1. What Is The Specific Function of A. The MergerLaura Garcia100% (1)

- Trendsetter S Two RoadsDocumento16 páginasTrendsetter S Two Roadsরাফিউল রিয়াজ অমিAún no hay calificaciones

- Zip Co Ltd. - Acquisition of QuadPay and Capital Raise (Z1P-AU)Documento12 páginasZip Co Ltd. - Acquisition of QuadPay and Capital Raise (Z1P-AU)JacksonAún no hay calificaciones

- In-Class Project 2: Due 4/13/2019 Your Name: Valuation of The Leveraged Buyout (LBO) of RJR Nabisco 1. Cash Flow EstimatesDocumento5 páginasIn-Class Project 2: Due 4/13/2019 Your Name: Valuation of The Leveraged Buyout (LBO) of RJR Nabisco 1. Cash Flow EstimatesDinhkhanh NguyenAún no hay calificaciones

- Koito Case Questions 2,3,4Documento2 páginasKoito Case Questions 2,3,4Simo RajyAún no hay calificaciones

- Lecture Notes Topic 6 Final PDFDocumento109 páginasLecture Notes Topic 6 Final PDFAnDy YiMAún no hay calificaciones

- Case PPLS Questions 20170412Documento2 páginasCase PPLS Questions 20170412Ernest ChanAún no hay calificaciones

- This Study Resource WasDocumento9 páginasThis Study Resource WasVishalAún no hay calificaciones

- RJRDocumento4 páginasRJRliyulongAún no hay calificaciones

- Ipo Guide 2016Documento88 páginasIpo Guide 2016Rupali GuravAún no hay calificaciones

- RJR Nabisco Holdings Capital CorporationDocumento3 páginasRJR Nabisco Holdings Capital CorporationManogana RasaAún no hay calificaciones

- Leveraged BuyoutDocumento9 páginasLeveraged Buyoutbharat100% (1)

- Bond Problem - Fixed Income ValuationDocumento1 páginaBond Problem - Fixed Income ValuationAbhishek Garg0% (2)

- Stone Container Corporation: Strategic Financial ManagementDocumento3 páginasStone Container Corporation: Strategic Financial ManagementMalika BajpaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Marriot Case Study CalculationsDocumento5 páginasMarriot Case Study CalculationsJuanAún no hay calificaciones

- Tax Rate Efectivo 14% Pagina 9Documento36 páginasTax Rate Efectivo 14% Pagina 9RodrigoHermosilla227100% (1)

- American International GroupDocumento3 páginasAmerican International GroupTep RaroqueAún no hay calificaciones

- 10 BrazosDocumento20 páginas10 BrazosAlexander Jason LumantaoAún no hay calificaciones

- RJR Nabisco 1Documento6 páginasRJR Nabisco 1gopal mundhraAún no hay calificaciones

- Case1 - LEK Vs PWCDocumento26 páginasCase1 - LEK Vs PWCmayolgalloAún no hay calificaciones

- Impairing The Microsoft - Nokia PairingDocumento54 páginasImpairing The Microsoft - Nokia Pairingjk kumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Calculating The NPV of The AcquisitionDocumento23 páginasCalculating The NPV of The Acquisitionkooldude1989100% (1)

- Michael McClintock Case1Documento2 páginasMichael McClintock Case1Mike MCAún no hay calificaciones

- 108 PBM #2 Winter 2015 Part 2Documento5 páginas108 PBM #2 Winter 2015 Part 2Ray0% (1)

- Capital Structure MSCIDocumento10 páginasCapital Structure MSCIinam ullahAún no hay calificaciones

- Bidding For Antamina QuestionsDocumento1 páginaBidding For Antamina QuestionsRazi UllahAún no hay calificaciones

- Arnab Roy Abhishek Mukherjee Anurag Rai Shauvik Ghosh Soumya C Pulak JainDocumento15 páginasArnab Roy Abhishek Mukherjee Anurag Rai Shauvik Ghosh Soumya C Pulak JainArnab RoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467 U.S. 752 (1984)Documento38 páginasCopperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467 U.S. 752 (1984)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Hertz QuestionsDocumento1 páginaHertz Questionsianseow0% (1)

- Formula One: Intangible Asset Backed Securitization (Uva-F-1323)Documento1 páginaFormula One: Intangible Asset Backed Securitization (Uva-F-1323)Shrikant Kr50% (2)

- Corning Convertible Preferred Stock PDFDocumento6 páginasCorning Convertible Preferred Stock PDFperwezAún no hay calificaciones

- FRAV Individual Assignment - Pranjali Silimkar - 2016PGP278Documento12 páginasFRAV Individual Assignment - Pranjali Silimkar - 2016PGP278pranjaligAún no hay calificaciones

- TargetDocumento11 páginasTargetAbbie Sajonia DollenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Team Members: S No Parameter Zencap Blackgem PreferredDocumento2 páginasTeam Members: S No Parameter Zencap Blackgem PreferredKshitishAún no hay calificaciones

- RJR 1987 Annual ReportDocumento94 páginasRJR 1987 Annual Reportmilken466100% (1)

- Williams 2002: - A Case On Financial DistressDocumento18 páginasWilliams 2002: - A Case On Financial DistressGmitAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileDocumento4 páginasCase Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileSubrata BasakAún no hay calificaciones

- Adecco Sa'S Acquisition of Olsten Corp: Group 6Documento6 páginasAdecco Sa'S Acquisition of Olsten Corp: Group 6Aditya AnandAún no hay calificaciones

- CorningDocumento2 páginasCorningVan KommAún no hay calificaciones

- Case QuestionsDocumento8 páginasCase QuestionsUsman ShakoorAún no hay calificaciones

- UVA-F-1264: Printicomm's Proposed Acquisition of Digitech: Negotiating Price and Form of PaymentDocumento14 páginasUVA-F-1264: Printicomm's Proposed Acquisition of Digitech: Negotiating Price and Form of PaymentKumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Songy PresentationDocumento10 páginasSongy PresentationRommel CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Executive Compensation: Ethical Issues: Presented By:-Group 10Documento29 páginasExecutive Compensation: Ethical Issues: Presented By:-Group 10Johnny KimAún no hay calificaciones

- Fin Magt Full BookDocumento200 páginasFin Magt Full BookSamuel DwumfourAún no hay calificaciones

- Leverage Buyout - LBO Analysis: Investment Banking TutorialsDocumento26 páginasLeverage Buyout - LBO Analysis: Investment Banking Tutorialskarthik sAún no hay calificaciones

- Padgett Paper Products Case StudyDocumento7 páginasPadgett Paper Products Case StudyDavey FranciscoAún no hay calificaciones

- DL 13dect1Documento90 páginasDL 13dect1Kit CheungAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study PP 2Documento42 páginasCase Study PP 2Anil BambuleAún no hay calificaciones

- M&A Case 1 - Group 7Documento8 páginasM&A Case 1 - Group 7ndiazl100% (1)

- Questions Immulogic BarkaiDocumento3 páginasQuestions Immulogic BarkaiVinesh SingodiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Deluxe Corporation Case StudyDocumento3 páginasDeluxe Corporation Case StudyHEM BANSALAún no hay calificaciones

- ImmuLogic Pharmaceutical1Documento4 páginasImmuLogic Pharmaceutical1awesomelycrazy0% (1)

- SeminarKohlerpaper PDFDocumento35 páginasSeminarKohlerpaper PDFLLLLMEZAún no hay calificaciones

- CLO Investing: With an Emphasis on CLO Equity & BB NotesDe EverandCLO Investing: With an Emphasis on CLO Equity & BB NotesAún no hay calificaciones

- ADR Final Case DigestDocumento6 páginasADR Final Case DigestHarold ApostolAún no hay calificaciones

- UN - Towards Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento17 páginasUN - Towards Sustainable Developmentviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- ACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.Documento3 páginasACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.viva_33100% (3)

- Romero v. CA DigestDocumento3 páginasRomero v. CA Digestviva_33100% (2)

- Carrascoso, Jr. v. Court of AppealsDocumento11 páginasCarrascoso, Jr. v. Court of Appealsviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- FINALS Case Digests CompilationDocumento154 páginasFINALS Case Digests Compilationviva_3388% (8)

- Republic v. Albios DigestDocumento2 páginasRepublic v. Albios Digestviva_3375% (4)

- Chapter 10Documento35 páginasChapter 10stephanier_24Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rosenblatt v. Getty Oil CoDocumento2 páginasRosenblatt v. Getty Oil Coviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Coggins V New England 1986Documento4 páginasCoggins V New England 1986viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Flight of Ideas: Top 10 Filipino Expressions I Wish To Hear Less in 2014Documento4 páginasFlight of Ideas: Top 10 Filipino Expressions I Wish To Hear Less in 2014viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- PLOS ONE: Non-Visual Effects of Light On Melatonin, Alertness and Cognitive Performance: Can Blue-EnDocumento10 páginasPLOS ONE: Non-Visual Effects of Light On Melatonin, Alertness and Cognitive Performance: Can Blue-Enviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Salvacion v. Central Bank of The Phil.Documento12 páginasSalvacion v. Central Bank of The Phil.viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- City Capital Associates VintercoDocumento2 páginasCity Capital Associates Vintercoviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- TSC Industries Inc. v. Northway Inc.Documento2 páginasTSC Industries Inc. v. Northway Inc.viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Credit Summary Table 1Documento2 páginasCredit Summary Table 1viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Santa Fe Industries Vs GreenDocumento4 páginasSanta Fe Industries Vs Greenviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Schneider v. Lazard Freres & Co.Documento2 páginasSchneider v. Lazard Freres & Co.viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Donovan v. Bierwirth - IdaDocumento2 páginasDonovan v. Bierwirth - Idaviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Georgia Pacific CorporaitonDocumento3 páginasGeorgia Pacific Corporaitonviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- McCullough v. BergerDocumento12 páginasMcCullough v. Bergerviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Credit Summary Table 2Documento2 páginasCredit Summary Table 2viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Credit Summary Table 3Documento2 páginasCredit Summary Table 3viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"Documento31 páginasRules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Securities Law OutlineDocumento7 páginasSecurities Law Outlineviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- $yllabus - Special Labor LawsDocumento8 páginas$yllabus - Special Labor Lawsviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"Documento31 páginasRules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Writ of KalikasanDocumento22 páginasWrit of Kalikasanviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Deposit Own DigestsDocumento12 páginasDeposit Own Digestsviva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- FINA 652 Private Equity: Class I Introduction To The Private Equity IndustryDocumento53 páginasFINA 652 Private Equity: Class I Introduction To The Private Equity IndustryHarsh SrivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Interview FBI Hostage Negotiator Chris VossDocumento16 páginasInterview FBI Hostage Negotiator Chris Vosspipul36Aún no hay calificaciones

- RJR Nabisco LBODocumento5 páginasRJR Nabisco LBOpoojaraneifm25% (4)

- CBMDocumento31 páginasCBMGaurav BhaleraoAún no hay calificaciones

- Private Equity Primer (Wiki Collection)Documento83 páginasPrivate Equity Primer (Wiki Collection)vincentparleAún no hay calificaciones

- Private EquityDocumento25 páginasPrivate EquityAman SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Battle of Gettysburg EssayDocumento8 páginasBattle of Gettysburg Essayafabfoilz100% (2)

- Barbarians at The Gate: Penguin Readers FactsheetsDocumento4 páginasBarbarians at The Gate: Penguin Readers FactsheetssagibaAún no hay calificaciones

- Leveraged BuyoutDocumento9 páginasLeveraged Buyoutbharat100% (1)

- Barbarein at The GateDocumento5 páginasBarbarein at The Gatemahesh.mohandas3181Aún no hay calificaciones

- RJR - NabiscoDocumento37 páginasRJR - NabiscoAB100% (1)

- Vault Guide To PEDocumento96 páginasVault Guide To PEBrandon Paquette75% (4)

- RJRJRJJRJRJRJJR111111Documento4 páginasRJRJRJJRJRJRJJR111111John Paul Chua57% (7)

- In Re RJR Nabisco Inc.Documento3 páginasIn Re RJR Nabisco Inc.viva_33Aún no hay calificaciones

- Venture Capital ProjectDocumento102 páginasVenture Capital ProjectAliya KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- History History of Private Equity and Venture CapitalDocumento5 páginasHistory History of Private Equity and Venture Capitalmuhammadosama100% (1)