Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Morony Review Bulliet Cotton Camels Nishapur

Cargado por

zamindarDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Morony Review Bulliet Cotton Camels Nishapur

Cargado por

zamindarCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Daniel Zakrzewski

Richard W. Bulliet, Cotton, Climate, and Camels in Early Islamic Iran: A Moment in World History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010, 184 pp, ISBN-978-0231148368.

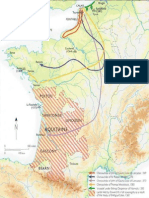

Richard Bulliet has long been a renowned scholar of numerous subjects related to Iranian history in the early Islamic period, including local politics, patterns of conversion to Islam and the domestication of camels. In his latest study, Bulliet demonstrates that the Iranian plateau region underwent a radical transformation in economic, social, cultural and ecological terms from the ninth century to the early twelfth century and asserts that the economic and ecological factors contributing to historical change are not taken into consideration sufciently by historians of the Middle East. These factors are fundamental to Bulliets approach, yet he also takes into account the part human agency played in those transformative changes. The rst four chapters of this concise, but rich study develop two main theses. First, the Iranian plateau region experienced a cotton boom during the ninth and tenth centuries; this turned it into one of the most dynamic areas of the Islamic caliphate, but came to an end as the agricultural economy generally declined as a result of climatic cooling in the eleventh century. Second, the colder weather was the initial trigger for the large scale inux into Iran of Turkic nomads who were to occupy a prominent position in the countrys politics for many centuries to come (p. 1). The nal chapter of the book summarises the general argument and presents in conclusion ve ways in which these transformative changes and their consequences can be considered to be of world historical signicance. Particularly noteworthy is the authors thorough documentation of the fact that from the early ninth century onward, the piedmont areas around the garrison towns established by the Arab-Muslim conquerors became major centres for both cotton plant cultivation and the production of and trade in cotton cloth. Among his sources are biographical dictionaries, tax registers and scientic treatises, while the analysis of place and personal names constitutes his principal methodological tool. He argues that the new Islamic landownership regime encouraged investment in specic irrigation systems which enabled the growing of cotton and led to the foundation of villages to house workers recruited for this purpose (p. 24). Arab Muslims and early Persian converts were highly involved in the cotton industry, Islamic scholars had ties to it and the cloth gained cultural signicance as a marker of Muslim aesthetics, as opposed to silk, which signalled a sentimental attachment to the Sassanid Empire (p. 51). Considering the method of forming work teams to found cotton-farming villages, Bulliet suggests a link between cotton and conversion to Islam in parts of the country and asserts that the protability of the cotton business and an ensuing process of urbanisation may by the tenth century have led to a reduction in the rural workforce engaged in food production (pp. 6567). At the same time, however, cotton had already lost much of its cultural signicance among the elite strata of society and the boom petered out as general economic and social conditions constantly worsened (p. 84).

NOMADIC 148 NOMADIC PEOPLES PEOPLES (2011) doi: 10.3167/np.2011.150108 (2011) VOLUME 15,VOLUME ISSUE 1, 2011: 15 ISSUE 148150 1 ISSN 0822-7942 (Print), ISSN 1752-2366 (Online)

Review

According to the author, the major cause of this deterioration was the severe chilling of the Iranian climate that set in early in the eleventh century (p. 69). This postulation forms the basis of his second main thesis which he underpins by drawing on analyses of tree rings in Mongolia and anecdotal evidence from historical and travel accounts and, then, relates to one particular political context. Bulliet claims that the colder weather also endangered essential parts of the livestock of camel-breeding Oghuz Turkmen nomads, so that a rst group of them sought and obtained from a regional ruler permission to migrate from the northern fringes of the Karakum desert to its southern edge in north-eastern Iran, around the turn of the tenth century (p. 104). With respect to the environmental features of these regions, he asserts that these Oghuz specialised in crossing male two-humped camels with female one-humped camels; the hybrids were particularly well suited for long-distance caravan trade and military mounts and were marketed as such by the Oghuz (pp. 1123). Their migration must have involved intense political negotiations within the nomadic community as well as with the regional ruler whose expectations of benetting from this move were not, however, to be fullled. Bulliet argues that when the cold became more severe in Iran, too, they were no longer able to keep the one-humped camels and turned to marauding in the countryside, further destabilising the already suffering rural economy. Mindful of this development, that rulers successor refused a similar migration by a second group of Oghuz Turkmen led by the Seljq family a generation later, but they defeated his forces militarily at Dandanqn in 1040 and, during the following decades, established an empire encompassing great parts of Iran and Central Asia and reaching far into Anatolia and Iraq (p.116). As regards the world historical signicance of changes occurring over the entire period, the author picks out effects on the economic, linguistic, religious and political geography of Iran and the Middle East that did indeed affect the course of world history (pp. 13743). However, given that he asserts that climate change was the major cause of the rst Oghuz migrations, he should have included factors other than temperature, especially rainfall and humidity, and could have gathered more reliable data to back this, probably correct, assertion. Moreover, some of his conclusions seem rather too simplistic and he dismisses the political arguments raised in historical accounts a little too carelessly. (For an analysis of these matters and additional references on climate change, see: Peacock, A.C.S. 2010, Early Seljq History, Routledge, pp. 3746.) Nonetheless, by emphasising the economic and ecological factors affecting the political history of this period and region and, more specically, by highlighting the danger posed to cold-sensitive camels, a major economic asset of the nomadic Oghuz, Bulliets approach provides an explanatory rationale for their rst migrations into Iran that, it may be hoped, will promote discussion, including beyond the circle of specialists in early Islamic Iranian history. The books appealing written style, its thorough explanations of specic problems and its regular summaries of the

VOLUME 15

ISSUE 1

NOMADIC PEOPLES

(2011)

149

Daniel Zakrzewski

various threads of the argument make it a study well suited to serve as starting point for debate. Daniel Zakrzewski Seminar fr Arabistik und Islamwissenschaft Orientalisches Institut der Martin-Luther Universitt Halle-Wittenberg, Germany daniel.zakrzewski@orientphil.uni-halle.de

150

NOMADIC PEOPLES

(2011)

VOLUME 15

ISSUE 1

Copyright of Nomadic Peoples is the property of Berghahn Books and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

También podría gustarte

- Qalanisi - Amedroz - History of DamascusDocumento460 páginasQalanisi - Amedroz - History of DamascuszamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Albert Us Magni ViiDocumento807 páginasAlbert Us Magni ViizamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Saladdin LIfe of Saladdin Life of SaladinDocumento471 páginasSaladdin LIfe of Saladdin Life of SaladinzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- 01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)Documento736 páginas01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)zamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Florida Do Not Call ProgramDocumento1 páginaFlorida Do Not Call ProgramzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Poblome Bes WilletArchaeologicalResidueNetworksDocumento10 páginasPoblome Bes WilletArchaeologicalResidueNetworkszamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Treaty of Brétigny/Calais (1360) and The Campaigns of The Second Phase of The WarDocumento1 páginaThe Treaty of Brétigny/Calais (1360) and The Campaigns of The Second Phase of The WarzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- BNCATANTIQUEDocumento661 páginasBNCATANTIQUEzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Only Desalination That Pays For Itself!Documento10 páginasThe Only Desalination That Pays For Itself!zamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- ABedoueen romantzBedouinRumArabLitDocumento425 páginasABedoueen romantzBedouinRumArabLitzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- AIA Program 2013 Web American ArchaeologyDocumento62 páginasAIA Program 2013 Web American ArchaeologyzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- BGAVIIIDocumento564 páginasBGAVIIIzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Al FakhriDocumento557 páginasAl FakhrizamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- EpistolaeMoguntinae Monumenta MoguntinaDocumento774 páginasEpistolaeMoguntinae Monumenta MoguntinazamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- 01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)Documento736 páginas01-02 Bd. I. 1-2 (Aal-Apollokrates)zamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Amphorae BibDocumento15 páginasAmphorae BibzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Inbaa Ghomr 01Documento585 páginasInbaa Ghomr 01zamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- Kitab Hulat IIDocumento478 páginasKitab Hulat IIzamindarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Radio Network Parameters: Wcdma Ran W19Documento12 páginasRadio Network Parameters: Wcdma Ran W19Chu Quang TuanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Hawthorne Studies RevisitedDocumento25 páginasThe Hawthorne Studies Revisitedsuhana satijaAún no hay calificaciones

- Poet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry PDocumento3 páginasPoet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry Pkarla telloAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEDocumento15 páginasChapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEyosef gemessaAún no hay calificaciones

- Maria MakilingDocumento2 páginasMaria MakilingRommel Villaroman Esteves0% (1)

- Chpater 2 PDFDocumento44 páginasChpater 2 PDFBilalAún no hay calificaciones

- Challenges For Omnichannel StoreDocumento5 páginasChallenges For Omnichannel StoreAnjali SrivastvaAún no hay calificaciones

- Business Finance and The SMEsDocumento6 páginasBusiness Finance and The SMEstcandelarioAún no hay calificaciones

- Top 100 Questions On Modern India History PDFDocumento16 páginasTop 100 Questions On Modern India History PDFmohammed arsalan khan pathan100% (1)

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiDocumento6 páginasPaediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiharnizaAún no hay calificaciones

- A Quality Improvement Initiative To Engage Older Adults in The DiDocumento128 páginasA Quality Improvement Initiative To Engage Older Adults in The Disara mohamedAún no hay calificaciones

- Large Span Structure: MMBC-VDocumento20 páginasLarge Span Structure: MMBC-VASHFAQAún no hay calificaciones

- Practice Test 4 For Grade 12Documento5 páginasPractice Test 4 For Grade 12MAx IMp BayuAún no hay calificaciones

- Nielsen & Co., Inc. v. Lepanto Consolidated Mining Co., 34 Phil, 122 (1915)Documento3 páginasNielsen & Co., Inc. v. Lepanto Consolidated Mining Co., 34 Phil, 122 (1915)Abby PajaronAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Paper 701Documento13 páginasResearch Paper 701api-655942045Aún no hay calificaciones

- Process of CounsellingDocumento15 páginasProcess of CounsellingSamuel Njenga100% (1)

- Tamil and BrahminsDocumento95 páginasTamil and BrahminsRavi Vararo100% (1)

- CEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design DescriptionDocumento44 páginasCEI and C4C Integration in 1602: Software Design Descriptionpkumar2288Aún no hay calificaciones

- 1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Documento99 páginas1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Munir HussainAún no hay calificaciones

- Book of Dynamic Assessment in Practice PDFDocumento421 páginasBook of Dynamic Assessment in Practice PDFkamalazizi100% (1)

- 04 RecursionDocumento21 páginas04 RecursionRazan AbabAún no hay calificaciones

- Syllabus/Course Specifics - Fall 2009: TLT 480: Curricular Design and InnovationDocumento12 páginasSyllabus/Course Specifics - Fall 2009: TLT 480: Curricular Design and InnovationJonel BarrugaAún no hay calificaciones

- Unified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsDocumento7 páginasUnified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsKANNAN MANIAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Develop Innovators: Lessons From Nobel Laureates and Great Entrepreneurs. Innovation EducationDocumento19 páginasHow To Develop Innovators: Lessons From Nobel Laureates and Great Entrepreneurs. Innovation Educationmauricio gómezAún no hay calificaciones

- Great Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Documento2 páginasGreat Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Luth ClariñoAún no hay calificaciones

- Proto Saharan Precursor of Ancient CivilizationsDocumento175 páginasProto Saharan Precursor of Ancient CivilizationsClyde Winters100% (4)

- Viva QuestionsDocumento3 páginasViva QuestionssanjayshekarncAún no hay calificaciones

- ID2b8b72671-2013 Apush Exam Answer KeyDocumento2 páginasID2b8b72671-2013 Apush Exam Answer KeyAnonymous ajlhvocAún no hay calificaciones

- Design Thinking PDFDocumento7 páginasDesign Thinking PDFFernan SantosoAún no hay calificaciones

- In Mein KampfDocumento3 páginasIn Mein KampfAnonymous t5XUqBAún no hay calificaciones