Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Article RBPH 0035-0818 1995 Num 73 3 4027

Cargado por

Sílvia MônicaDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Article RBPH 0035-0818 1995 Num 73 3 4027

Cargado por

Sílvia MônicaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Gnther Kress

Moving beyond a critical paradigm : on the requirements of a social theory of language

In: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. Tome 73 fasc. 3, 1995. Langues et littratures modernes - Moderne taalen letterkunde. pp. 621-634.

Citer ce document / Cite this document : Kress Gnther. Moving beyond a critical paradigm : on the requirements of a social theory of language. In: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. Tome 73 fasc. 3, 1995. Langues et littratures modernes - Moderne taal-en letterkunde. pp. 621-634. doi : 10.3406/rbph.1995.4027 http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/rbph_0035-0818_1995_num_73_3_4027

Gnther Kress 1 .

Moving beyond a critical paradigm : on the requirements of a social theory of language

A personal comment The editors of this journal have kindly invited me to give a relatively personal account of work under the broad label of Critical Linguistics. I am honoured by this invitation and eager to meet their challenge to provide such an account, and to speculate, beyond the present, on likely future needs and directions in this area of linguistic theorizing and practice. All human work and achievement rests on the work of many, a fact which it is crucial to acknowledge. All of what I have done has been informed by the work and thoughts of many others. Yet here I will make full use of the generous offer to speak from a personal perspective, without the usual requirements of objectivity and judicious balance, and therefore this paper simply provides just one perspective on what is now a considerable body of work. The critical paradigm in the study of language is not confined to those who use the term critical ; feminist work on language is one such prominent instance. However, I do not wish to recruit others to a project they might not wish to join ; nor do I wish to extend, imperialistically, a label to the work of others whose histories, motivations and modes of working have been different, and arose in quite different contexts. My lack of acknowledgement of cognate work in the body of this text should be seen in this light. 2 . Critical Linguistics Critical Linguistics was, in its early formulations, a response to three questions : What is it that gives rise to linguistic organization and form ? ; What, therefore, is a plausible theory of language ? ; and, How can the discipline of linguistics be reformed so as to be socially responsive and responsible ? In Critical Linguistics (C.L.) these were seen as entirely related, given the answer to the first of these three questions : linguistic form and organization is the result, an effect, a product of social practices and forms of social organization. This formulation reveals the origins of the theory in what has (fashionably) become known as crude Marxism , the theory of the relation of base and superstructure. In this theory the form of economic organization is seen to give rise to forms of social organization, such as class-structures ; the regularized distributions of power and consequent power-differences ; structures of oppression and domination ; but also, to the organization of other superstructural categories such as literature, law, and, from this point of view, language. This formulation is of course also an echo of Michael Halliday's phrase that language is as it is because of the functions which it serves in society . Both make social (and economic, as a form of the social) categories prior in an account of linguistic form and organization, and of the linguistic system . Both

622

GNTHER KRESS

formulations explicitly or implicitly pose the second question : what is a plausible theory of language ? That question in itself suggested of course that existing theories of language did not provide plausible accounts of language, for at least two reasons. One, mainstream theories of language (at that time largely the Chomskian paradigm) insisted strongly on the autonomy of the language system, and therefore on the autonomy of linguistics as a discipline ; and two, structuralist theories of language (including transformational generative theory) held to a strongly psychological basis for an account of language ( language is as it is because of the nature of the brain or the "mind" ). Neither of these allowed a connection with the social ; and indeed that connection was rigorously rejected in the Chomskian paradigm. In that respect, then, mainstream linguistics was uninterested in any issues of social responsiveness or responsibility that is, being useable as a theory for attempts at a critique or perhaps even a remaking of social organization. Indeed, that kind of question was not and could not be put in mainstream linguistics : it provoked anger, ridicule, hostility, and contempt. Attempts to publish Language as Ideology (the first draft of which was completed in 1974) remained unsuccessful for at least three years, and it was only through a combination of factors largely, an editor willing to take a risk ; and a colleague, Roger Fowler, with an already established reputation, becoming a co-author in an associated volume, Language and Control that the book found a publisher, in late 1977. With a very few exceptions, the history of its reception by reviewers, was a similarly bleak story, oscillating, generally speaking, somewhere between the vitriolic and apoplectic, and the contemptuously dismissive. In its initial stages C.L. focused less on the aim of developing a plausible theory of language than on the third question : how can the discipline of linguistics be reformed to become socially responsive and responsible ? While this aim in itself had two aspects, attempts at the reform of a discipline, and attempts at an effect on social arrangements , it was largely the second of these that was pursued. The expectation was that telling analyses of texts would lay bare systematic inequities in social relations and in distribution of power, and through their revelation permit an examination by individuals of their own actions, and through such examination offer the possibility of less prejudicial action by those who were able to see ; or offer the possibility of effective resistance by all members of a social group to the imposition and continuation of social inequities. There was of course always the hope that the effectiveness of these analyses would convince fellow linguists of the strength and efficacy of this theoretical (even if not of the political) position and lead them to reflect on the linguistic framework they were using, and on its potential ideological and social effects. In practical, everyday terms, the intellectual and academic environment at the University of East Anglia made it possible to develop linguistics in that direction. The university held to a strongly interdisciplinary model, which was expressed in degree regulations as much as in ordinary teaching practices. It was possible to

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE

623

conduct classes offered jointly by literary scholars and linguists, by linguists and philosophers, by sociologists and linguists, and eventually and at that time quite outrageously to suggest that the form of linguistics that was being developed might be of interest to historians. That daring suggestion bore fruit when one student won a national History prize for a linguistically detailed, historical analysis of some letters of Oliver Cromwell's. What had seemed a marginal and struggling subject, in the context of giants such as Literature, History, Sociology, began to show its potential as a contributor at a foundational level in research and scholarship. In that, C.L. was part of a more broadly based educational movement at the university at that time (and particularly in the school of English and American Studies) towards greater relevance of the curriculum, and useability of the various disciplines. Linguistics, being in a position of marginality, perhaps felt the need to be relevant to and useable by other disciplines more keenly than disciplines which were central , large, and unthreatened. 3 . Critical Linguistics and the linguistic mainstream The goal of developing a socially responsible and responsive linguistics may seem, in retrospect, somewhat perverse, given the existence of the already lively branch of linguistics, sociolinguistics, at that time. The work of Labov was well established, as was the work of Hymes, Fishman, Gumperz, Bernstein ; or, in a different vein, the critique of sociolinguistics provided by Dittmar, in Germany. Ethnomethodology was producing fine-grained descriptions, at a micro-level, of linguistic interactions, in various forms. However, these enterprises, important in different ways, and in the case of the work of Hymes and Bernstein, for instance, producing foundational questions for the discipline , did not ask what seemed central questions for C.L. : about the relation of social organization and linguistic form, connected to the form of a plausible theory of language. The work of Labov, seminal in other ways, for instance in pointing clearly to the link between social organization and linguistic change, may stand as an example. In his hugely influential article The Logic of Non-Standard English , he used the theoretical model of transformational generative grammar for a purpose which was alien both to it and to the main and underlying theoretical orientation of his own work generally. The universalist and mentalist model of Chomsky's account of language was totally at odds with Labov's attempts to show, in his other work whether about language use and development in Martha's vineyard, or language use in the inner city the fine calibration and correlation of social position and its expression in linguistic form. The use of an inappropriate linguistic model skewed his own purposes : even if, it has to be said, to wide popular acclaim. Black English was reduced, in his description, to a version of White English. It remains the standard against which non-standard forms are uncritically assessed ; differences between Black Culture and White Culture are reduced to mere surface phenomena ; and the victims, as is often the case, are blamed for their plight even if only implicitly, in this instance.

624

GNTHER KRESS

A theory which posits an integral link between the form of social organization and the form of linguistic organization, such as C.L., could not have come up with Labov's conclusion. Black English and White (middle-class) English would have had to be seen as different. The differences in the linguistic form and organization of these two dialects of English would have been seen as entirely related to, explained and determined by the social organization of the social groups using the two forms. In order to establish the causal, determining link between the social and the linguistic, C.L. developed a framework which drew its categories from two quite distinct linguistic theories : the mentalist, structuralist, universalist model of transformational generative, from which it took the category of transformation first and foremost ; and the social, functional, and praxis oriented model of systemic functional grammar, from which it took the notion of choice in context first and foremost. What united the framework and gave it cohesion was a view of users of language seen as active, as makers of the linguistic forms which they used in communication, whether as clauses, sentences or text. Hence, the concept of transformation which was taken as a realist model, that is, a view of transformation as meaning-changing processes, this was put with the notion of choice in context, again an active notion, which saw the speaker as actively making decisions in the awareness of a rich context. In the mainstream linguistic / syntactic theory ofthat time (as contrasted with its uses in stylistics, and in certain versions of experimental psychology), the issue of realist interpretation had become less focal, and a broad commonsense had developed in favour of the non- realist account. For the initial version of C.L. the attraction of both a realist interpretation of transformation and of choice, was that both took for granted the motivated action of the language user in a particular context. Treating the language user as active psychologically, cognitively, socially, for instance as the active agent of a transformation, whether of passivization or nominalization or of a movement-transformation, turns the user of language into the maker of a linguistic form. The addition of the category of choice insists on the fact that that action takes place out of an awareness of the complex structures of a larger social context in which other kinds of actions are possible, with greater or lesser degrees of constraint. The choice of this action deleting the agent-noun of a passive clause for instance rather than that action not deleting the agentnoun, or nominalizing the clause instead of passivizing it, for instance is thus at the very least the expression of the language user's preference , which itself rests on an assessment of the aptness of this choice that has been taken as against those which have not been taken. In this way language users were seen as makers of form (actively implementing a transformation, for instance), and as actively selecting, in the knowledge of other possible choices. These together could be seen as the meaning of a particular linguistic form, whether of a larger syntactic complex,

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE

625

a part of such a complex, or, of the more complex patternings of texts produced by one or more speakers or writers. This move locates the relation of C.L. within the linguistic mainstream. On the one hand it was prepared to take, seemingly eclectically, categories from quite divergent theoretical paradigms, as in this instance with these two foundational categories. On the other hand this same move set it off distinctively even if this might not have been fully realized at the time or, in some ways since from the mainstream and the tributaries, offshoots, billabongs and backwaters of linguistic work. Let me expand on these two. The seeming lack of principle the eclecticism was not of course, in my view unprincipled. Transformations could be taken into a new model only as real psychological cognitive processes, whose motivation was itself provided by the category of choice. In one sense this opened a paradox, between the universalist / mentalist meanings adhering to transformation as a theoretical category (although it restored it to something like its original use in Zellig Harris' earlier work, and to that extent attempted to undo the Chomskian counter revolution), and the strongly socially and culturally oriented category of choice. Nevertheless there was an eclecticism, which in a sense derived from the aim of reforming mainstream linguistics. This encouraged a use of theoretical and descriptive categories developed in mainstream theories, on the assumption that these categories if integrated into the framework just described and, specifically, if given a realist interpretation on the basis of that - would be adequate as descriptive and analytic tools. The real differences between the theoretical and ideological foundations of the source-theories could be overlooked, on the assumption that they provided, at one level, apt descriptions of linguistic form or processes, adequate enough for the time being for this analytic task. In this fashion a highly diverse, eclectic bundle of categories was assembled, and, over the years expanded and extended, and generally speaking, never subjected to close theoretical analysis, or tested for their actual overall coherence. Systemic linguistics provided a functional framework, perhaps with greater focus on the ideational and interpersonal functions especially in the importance given to modality and transitivity ; transformational grammar of a mid-sixties kind provided the category of transformations especially passivization and nominalization. Later developments, in particular in Critical Discourse Analysis, drew on the enterprises of Pragmatics, of Conversation Analysis, on A.I, etc. In general, the more the project of social / ideological critique moved into the foreground, the less the other two questions concerned with theory could be focused on ; and broadly speaking, they receded. C.L. has thus remained in a client-status in relation to its source-theories : willing, or indeed obliged, to get its theoretical and descriptive categories from theories which have of course their quite distinct orientations and political / ideological implications. This relation to the mainstream is, in my view, a serious problem. It neither furthers the project of reform of the source-theories, nor does it allow C.L. to move on. At the moment there are moves, not in C.L. so much as in C.D.A., to address

626

GNTHER KRESS

this issue. There is the more recent theoretical work by Teun van Dijk, which aims at producing an integrated (and integrative) theoretical framework, and there are my own attempts for instance, differently focused, to produce at least the outlines of the requirements for a theory of language which would be apt for the stated enterprise of C.L. or CD. A. I will return to this in a moment. The second mode of relation to the mainstream or better, to its tributaries and backwaters exists by its absence. In principle C.L. (or C.D.A.) attempts to provide a theory of language which does not separate form from meaning syntax from semantics ; system from use, in the shape of oppositions between syntax and semantics, sociolinguistics or pragmatics ; pure theory from application ; stylistics from normal language use ; etc etc. These distinctions and proliferations arise in traditional, mainstream theories due to the insistence by linguistics both on the autonomy of language, and the autonomy of linguistics. Whenever questions of meaning or use show up they are shunted off to some peripheral area semantics, pragmatics, sociolinguistics, stylistics etc. Linguistics has been concerned nearly exclusively in this century with the signifier, with form. In this narrower area it has been remarkably successful, and its success has at least in part meant that C.L. could rely reasonably well on the grammatical descriptions provided in mainstream linguistics over the last few decades. 4. Current Issues The critical paradigm in the study of verbal texts has been productive, and to a considerable extent persuasive. In current work the distinctions between C.L. and C.D.A. have become quite blurred ; the methodologies, as well as the theoretical and political aims of the former have been taken into the latter. Related strands of this work have appeared Critical Language Awareness, for instance, as a kind of political-cum-pedagogical project. Again, it draws on the methodologies of C.L. and C.D.A. Its efforts are a part of the extension of this mode of working, and in that, C.D.A. illustrates what is generally speaking one of the central current issues : actual application. Whereas earlier work in C.L. (and C.D.A.) provided analyses more or less as means of exemplifying theoretical issues this is what should and could be done , this is what this kind of theory can deliver the emphasis now is much more on actual uses. Roger Fowler's Language in the News (1992) falls into this category, as does Paul Chilton's earlier Language and the Nuclear Arms Debate (1985). Teun van Dijk's extended studies of racism, sexism, and discriminatory and prejudicial uses of language are instances (1987, 1988), as is the work of Ruth Wodak on racism and anti-semitism (1994). In a different direction, the largely Australian initiated work in language and education has focused on the issue of a literacy curriculum, largely through a development of the concept of genre in the direction of genre as text-types produced in social practices. This strand of work can serve to illustrate a particular problem with current work in the family of critical language studies : most of the linguists and educators working with genre or on its theoretical development and

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE

627

elaboration (characteristically the distinction of application / theoretical work ) would probably not see themselves as doing C.L. (or C.D.A.), even though they would readily acknowledge the family-connection. The problem is that in the focus on a particular application of C.L. in certain fields of social practice, concerns with the theoretical coherence of the overall framework are very much secondary. This problem is intensified by the fact that the family of critical language work has expanded as much by organic modes of reproduction as by newer forms of family structure : adoption, mixed families, informal partnerships and liaisons. In other words, practitioners in the field have come from many places, and happily, the family has not insisted on inquiring into genealogy. This is in part the major reason for my personal note prefacing this article : the work of Teun van Dijk for instance has one history, that of Roger Fowler a different one, that of Ruth Wodak another, that of Norman Fairclough or myself yet others, and so on. It is the political interest in using linguistic / textual analysis for the ends of social change and reform which both has brought academics together, and keeps them together, relatively happily, under the family label. It makes it important and difficult to speak for this strand of work, and especially to attempt to speak as though it were a theoretically or methodologically unified enterprise. There are certain strengths as much in the willingness to work with or to ignore differences : it feeds new questions, new concerns, into the pot of issues that have to be dealt with. Equally it has clear weaknesses in that there are no agreed on or unified methodologies. A student new to the field would recognize the similarity of political aims, but might be exasperated by the very different theoretical and methodological approaches. In part it is the recognition of this which has led individuals as I mentioned earlier and some of the practitioners collectively to ask about the possibility of bringing about some degree of coherence in the framework, or to move towards the development of an integrative theoretical framework. In the meantime, the fact that it is the political rather than a more recognizably theoretical project which provides coherence, can and has led hostile critics to accuse C.L. and C.D.A. of being merely political : that is, not (properly) academic. While I personally am not deeply troubled by such charges, especially given the absence of reflexivity by such critics on the politics of all academic practice, it nevertheless delivers a particular hostage to those who are not well-inclined, and can act as a deterrent to others who might initially be worried about such charges. For me the more significant issue is that which I mentioned earlier, namely that the political project of this family of approaches implies and demands a theory of language other than those from which it at present draws its concepts. C.L. and C.D.A. cannot afford, theoretically and politically, to remain in a client status in relation to forms of linguistics which in their ideological / political constitution are fundamentally and problematically distinct whether as mere difference, or as implicit hostility and antagonism. The lack of the development of a theory of

628

GNTHER KRESS

language which is apt to the purpose of C.L. or CD. A. has detrimental effects. For one thing it leaves the formulation of the commonsense about language with deeply problematic paradigms ; for me, working in the institution of education, of pedagogy, at the moment, the theories of language which form and define popular (or professional) common-sense are an enormous problem in thinking about reforms of language curricula in schools whether for first or other language learning and teaching. For another, and here I return to the first two questions, as an academic in this field, I am quite simply not happy with a situation where I am constantly forced to work against the grain of my theoretical and political disposition. In short, for me the urgent current issue is the development of a view of language, expressed as a theory, which is appropriate to the social and political position which I hold, and which, by happy coincidence, would be closer to the facts of language as I see them. These current issues, and attempts to address them, form for me, the future agenda of work in this area, and so I will deal with them under that heading. 5 . Futures A first and fundamental question to ask, in my view, is this : if the critical paradigm in language study has as its focus an engagement with and a reform of social arrangements, what follows when those social arrangements themselves begin to shift ? In other words, I cannot put, against a view of language as social practice, an a-historical theoretical position which is indifferent to changes in the social. If critique is essential at certain times in order to bring an ossified social system (and its power structures) into crisis, in order to produce the possibility of new social dynamics, what follows if the system, for quite other reasons, changes at an increasing rate, so that fluidity and social dynamic becomes the problematic issue ? Is critique alone then a sufficient or even a proper response ? Hence quite apart from my reasons so far advanced for the need for a retheorization of language from the point of view of C.L. or CD. ., there seems a further set of reasons for doing so, namely the set of questions posed by changes in the social for theorization of language. This is not the place for an account of these changes in any detail at all, but it is essential to mention a few, not in any systematic sense. The intensifications of cultural and linguistic diversity, intranationally and internationally accompanied by intensifications (for the time being) of the politics of difference, are having effects on language and language change. Changes in this, as in technologies of communication and information are producing shifts in what I call the semiotic and communicational landscape, displacing language in many domains of public communication form the centre of the communicational landscape, and reshaping its relation with other semiotic, representational and communicational media. This is not simply a displacement of language, leaving language itself intact, but it is producing fundamental changes in language, whether through the social effects

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE

629

of electronic forms of communication ; the effects of different conceptions of a reader by the producers of the newer multi-modal texts ; or by changes in the subjectivities, the linguistic habitus of language users themselves. I will confine myself to these, although these are powerfully amplified or even partially caused by the globalization of economies, of the media, and of finance. In this context apt theories of language will have to have plausible social accounts of social and linguistic change together with accounts of social and linguistic difference, as foundational elements. Equally, a plausible theory of language will have to have at long last strong accounts of the subjectivities of language users, and the reciprocal, integral, and dynamic relation between subjectivity and representational systems. Strong social accounts of text as the focal unit of a theory of language will need to be developed, indicating a shift away from sentence-based grammars which still inform, however implicitly, even the critical language paradigms. Implied in these changes is a need to recognize directly and overtly a shift in attention from signifier to sign, that is an attention to a unit which does not separate meaning and form but rather treats these as one entity (as Saussure indeed had indicated and demanded, nearly a century ago). The shift from signifier to sign entails of course, a shift from linguistics (or Discourse Analysis) to semiotics, a shift demanded in any case by the newer, multi- modal forms of text. A theory of this kind will not produce the distinctions of syntax and semantics, pragmatics, sociolinguistics, stylistics, etc etc, as these will become issues dealt with as an ordinary matter of course in the centre of the theory. As significantly, a theory of this kind will supersede the need for critical paradigms : these are necessitated at the moment precisely by the fact that dominant paradigms are not just uncritical, but theoretically constituted in a way that makes them incapable of critique. A theory of the kind I envisage will produce the descriptions which we now regard as critical as an ordinary matter of the implementation of the theory. In this paper I have produced no analyses, unusually for writing in C.L. or C.D.A., including my own. This is because on the one hand there is now a substantial body of work relatively easily accessible, and on the other hand I do feel that given the significant differences in modes of working it is important to look across the range of such work : this is definitely a place where I would not wish to speak for others. The bibliography will, I hope, give a sufficient indication of the work of people in this broad paradigm. However I do wish to give two very brief examples, to illustrate a set of points which underline my own thinking, and are not found in work so far produced. My first example concerns the complex interrelation of socially constituted subjectivities > remaking of the linguistic resources and therefore of the system > remaking, in that, of subjectivity > history and change as effects of personal interest and social histories. My second example points to the effects of the new semiotic landscape on language, through the effects of the multi-modal text.

630

GNTHER KRESS

Again, the complex here has social subjectivity at the centre, it involves disciplinary knowledge and its remaking, and the remaking of the linguistic as of the larger semiotic system. Is there such a thing in Japan still as the geisha girl/ or [gi:/a]... I'm not even sure how to pronounce it. Yes there is... And how free are they to do what they want these days? How free are they to do what they want... Within their work or outside of their work? Outside of their work as a woman... or are their whole lives about being subservient to men? But what they are doing isn't being subservient to men... it is real art form... they entertain with dance... with music... with intelligence And they entertain the man... is that right? Men They go through their training... or whatever it's called... purely to entertain men... is that right? Men... but sometimes men also have female guests. (laugh) Yea... yea... traditionally they have been trained to To entertain the male sector And is this still an important part of traditional Japanese society... the geisha girl? (laugh) No... it's another world... it doesn't relate to the average person's lifestyle in this city It's maybe close to a traditional art form. (interview on Sydney radio station 2-555 in the context of the International Year of Women). The first example is an extract from an interview on a popular youth oriented radio station in Sydney. The context is the international year of women. Two young Australian women have returned from Tokyo, where they worked as hostesses ; the young woman interviewer wishes to urge them to admit that they worked, effectively, as prostitutes. Understandably the two young women wish to resist this classification. My focus is on the syntax of entertain 11. 9-10 1.11 1. 12 11. 13-14 1. 15 1.17 entertain with dance nontransactive, instrumental, an action simply engaged in by the agent, though instrumentally. they entertain the man transactive : the interviewer's form the object is however abstract masculinity a non-count, mass noun. (they entertain) men the object is made concrete human; by the interviewer, this is her interest. purely to entertain men purely modalizes both men and entertain ; it acts as a covert negation. men... have female guests the implied object is guest , male and female. to entertain the male sector now the object noun of entertain is non-human ; the verb is transactive, but the noun is depersonalized, analogous to financial sector , service sector .

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE

631

In this brief battle, a number of ideological paradigms have been invoked. The one settled on here is that of the economic domain ; though aesthetics is settled on four lines further on. In my view the socially formed interests of the participants are fought out through the syntactic potential (among other things) of this small element. In the process the semantic and transitivity potential of entertain is changed. Entertaining the male sector is not the same socially or linguistically as entertaining men, (or) the man . But in this battle subjectivity is at issue as much as linguistic form. History in its micro- form is being made. My second example comes from a high-school text book in science. My interest here lies in the simplification evident in this language, in response, I assume, to a conception of the reader which has much to do with the mediation of science visually. Without again undertaking any detailed analysis, consider the first paragraph. y Electronics Transistors

need An conaucton silicon. eiecmcitv because same there and like In Circuits with the not You Transistors vour electronic transistors, bulbs very contacts circuits wont. wim basic are can Transisto-s first thev not little mane in have They ideal. It Modem circuits the many can vou is and are elecmcirv far been chips electronic nght are rum light made poor, But chips bener wires wont mar you electrical replace and conditions. on ifand betre. you 4tana used because or re to lint-emitting circuits from sometimes examples soidrr loot torch oil rautpment torch bv The special very inside electronic they bulbs. Thev the with difficulty bulbs of fast, components onlv things crystals are wires asemi, The diodes. computer uses loined and useful conduct devices wires like is do the thev like that

A transistor is a special semi-conauctor. It has three connections: a bas, a collector and an emitter When a small current is put on the bas, it lets a much larger current flow between the collector and the emitter So a nnv current can control a mucn larger one. Try this water-detector circuit.

Here is a simple circuit to operate a light-emitting diode (LED)

This design showt the same circuit soldered on mam board. The board is cheap and can be re used.

^Tj _ / small When current the probes goes from touch the something batterr through wet. very the water to the bas of the transistor. This current is big enough to make the transistor work, so the LEO lights up.

632

GNTHER KRESS

Address is direct In your first circuit you... The language is verbal rather than nominal (or nominalizing) You used torch bulbs... (rather than The usage I utilization of torch bulbs... ) ; the terminology attempts to be everyday rather than specialist. There are the scientific passives : have been replaced , but generally there is greater use of active voice. Sentences are short, generally of no more than two non- embedded clauses ; and so on. By contrast, my third and last example, a science book for the same agegroup, but from 60 years ago, has quite a different address : I will not provide any analysis here, and leave my statement at an impressionistic description : this is the language which had been characteristic of scientific text-book writing until recently ; it is a relation of language and the visual where language is central, and the visual does act as illustration, rather than as the main carrier of information. 76 MAGNETISM AND ELECTRICITY the magnetic poles. Fig. 62 (c) shows the combined Meld of (a) and (b) when the wire is placed between the poles. Note that, in Fig. 62 (a) and (6), the lines of force on the left of the wire are in the same direction as those of the external field, while those on the right of the wire are in the opposite direction. Consequently in the combined field of Fig. 62 (c) the field to the left of the wire is strong there are a large number of lines, while th field to the right is weak. If we assume, with Faraday, that the lines of force are in tension and trying to shorten (see p. IS), we should expect the wire to be urged to the right. This is precisely what we find by experiment.

( Fig. 2. (a) Magnetic field due to current in itralght wire, (b) Field due to magnetic pole, (c) Combined field of (a) and (6). The principle of the electric motor. The simple electric motor consists of a coil pivoted between the poles of a permanent magnet (see Fig. 63). When a current is passed through the coil in the direction indicated in the figure we can show, by applying Fleming's left-hand rule, that the lefthand side of the coil will tend to move down and the right-hand side to move up. (Remember that the direction of the field due to the permanent magnet is from the N. to the S. pole.) Thus the coil will rotate in a counter-clockwise direction to a vertical position.

(*)

ON THE REQUIREMENTS OF A SOCIAL THEORY OF LANGUAGE 6.

633

Language and ideology I have not focused strongly on the issue of ideology, and it might be felt that my interests in that respect have changed ; which is not the case. Consider the interview. Both the lexical shape and the transitivity potential of the verb entertain (and of its nominalized potential forms) is refashioned in the series of steps shown above. Each refashioning is an attempt by one party or the other to code their interest adequately : to provide an apt encoding of their position at that moment in linguistic form. But their position is as much an encapsulation of their social histories, their present social positions, as of their perception of the power-relations in the situation of interaction. What is coded (and contested) in this exchange is thus both social subjectivity and relations to power. The linguistic form codes these precisely. On this occasion, for a variety of reasons, the interviewees have greater power (it is the International Year of Women, and so it would not do for the interviewer to use her power to act oppressively in relation to other women), and it is therefore their representation which carries the day. But that is precisely (at least) one definition of ideology. A very similar account can be given of the second text. The writer / maker of this text has in mind who the young reader / viewer of this text is : the prominence of the visual may have led him via a current commonsense notion of the visual into assuming that science is being made pupil-friendly. But in this assumption it has to be made pupil-friendly because pupils are no longer willing or able or both to read texts such as text 3. Hence the simplification of the syntax. In this simplification of syntax, there are certain effects on what can be said in disciplinary terms technical terminology is avoided, and so there is a simplification not just of language but of the discipline. It is my contention that in this complex remaking of this pedagogic relation, we are witnesses again to the effects of ideological structures on linguistic form. In his introduction to Magnetism and Electricity, the source of Text 3, the author says It is... a readable book for the boy . My contention is that the change in syntax from Text 3 to Text 2 demonstrates among many other things, how this the boy has come to be the you of you used torch bulbs a complex social and thoroughly ideological history. 7. Bibliography CHILTON (P.), ed. Language and the nuclear arms debate : Nukespeak today (London : Frances Pinter, 1985). CHILTON (P.), Orwellian language and the media (London : Pluto Press, 1988). CHOMSKY (N.A.), Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (Harvard, Mass : M.I.T. Press, 1965). DlJK VAN (T.A.), News analysis. Case studies in national and international news in the press : Lebanon, ethnic minorities, refugees and squatters (Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987). DlJK VAN (T.A.), News as discourse (Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988).

634

GNTHER KRESS

FAIRCLOUGH (.), Language and Power (London : Longman, 1989). FAIRCLOUGH (N.), Discourse and social change (Cambridge : Polity Press, 1991). FOWLER (R.G.), Language in the news. Discourse and ideology in the press (London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1990). FOWLER (R.) et al., Language and Control (London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979). Halliday (M.A.K.), Language as Social Semiotic (London : Edward Arnold, 1979). HALLIDAY (M.A.K.), An introduction to functional grammar (London : Edward Arnold, 1985). HALLIDAY (M.A.K.), Introduction to functional grammar (London : Edward Arnold, 1994). HODGE (R.) and KRESS (G.), Transformations, models and processes : Towards a useable linguistics , Journal of literary semantics, 4 (1974) 1, pp. 4-18. HODGE (R.) and KRESS (G.) Social Semiotics (Cambridge : Polity Press, 1988). HODGE (R.) and KRESS (G.) Language as ideology, 2nd ed. (London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1993). KRESS (G.), Learning to write (London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982). KRESS (G.), Linguistic processes in sociocultural practice (London : Oxford University Press, 1989). KRESS (G.R.), Cultural Considerations in Linguistic Description in GRADDOL (D.), THOMPSON (L.) and BRYAN (M.), eds. (1993a) KRESS (G.R.), Language and Culture (Clevedon : Multilingual Matters, 1993b). KRESS (G.) and THREADGOLD (T.), Towards a social theory of genre , Southern review, 21 (1988) 3, pp. 215-243. KRESS (G.R.) and LEEUWEN VAN (Th.), Reading Images. The grammar of visual design (London : Routledge, 1995). MARTIN (J.R.), Factual writing : Exploring and challenging social reality (London : Oxford University Press, 1989). WODAK (R.) et al., in VORBER, Die Sprache der Vergangenheiten. ffentliches Gedenken in sterreichischen und deutschen Medien (Frankfurt/M : Suhrkamp, 1994). WODAK (R.), Formen rassistischen Diskurses ber Fremde in BRNNER (G.) u. GRAEFEN (G.), eds., Texte und Diskurse (Opladen : Westdeutscher Verlag, 1994).

También podría gustarte

- The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismDe EverandThe Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (8)

- Linguistic AnthropologyDocumento7 páginasLinguistic AnthropologyMary Nicole PaedAún no hay calificaciones

- Constructing Authority Languages and Publics: and RepresentationDocumento10 páginasConstructing Authority Languages and Publics: and RepresentationJavier Alvarez VandeputteAún no hay calificaciones

- Languages and Publics - The Making of Authority - Susan Gal, Kathryn A. Woolard (2001) - 9-18Documento10 páginasLanguages and Publics - The Making of Authority - Susan Gal, Kathryn A. Woolard (2001) - 9-18Mayra AlejandraAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociolinguistics - Origin PDFDocumento7 páginasSociolinguistics - Origin PDFZahid HossainAún no hay calificaciones

- Conceptualization of IdeologyDocumento9 páginasConceptualization of IdeologyHeythem Fraj100% (1)

- Language in Social GroupDocumento6 páginasLanguage in Social GroupFarida HamdaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse AnalysisDocumento55 páginasDiscourse Analysiskarim_showAún no hay calificaciones

- Kroskrity2015 LanguageIdeologies EmergenceElaborationandApplicationDocumento15 páginasKroskrity2015 LanguageIdeologies EmergenceElaborationandApplicationMayra AlejandraAún no hay calificaciones

- To Of: John J. Gum-Perz Dell HymesDocumento2 páginasTo Of: John J. Gum-Perz Dell HymesenviAún no hay calificaciones

- 10.1515 - Ijsl 2020 2084Documento10 páginas10.1515 - Ijsl 2020 2084AndrésAraqueAún no hay calificaciones

- 1964 HYMES - Directions in Ethno Linguistic Theory1Documento51 páginas1964 HYMES - Directions in Ethno Linguistic Theory1lijianxunzaiAún no hay calificaciones

- 2012LinguisticTheoriesApproachesandMethodsDraftversion PDFDocumento45 páginas2012LinguisticTheoriesApproachesandMethodsDraftversion PDFmica100% (1)

- 10.4324 9780203149812-2 ChapterpdfDocumento16 páginas10.4324 9780203149812-2 ChapterpdfNhi Nguyen PhuongAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse AnalysisDocumento3 páginasDiscourse AnalysisHibaalgurjiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociolinguistics' Antecedents Language History and ChangeDocumento11 páginasSociolinguistics' Antecedents Language History and ChangeDjihene ZeghadniaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sosiopragmatik 2013Documento3 páginasSosiopragmatik 2013ermalestari.22037Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fowler - Studying Literature As LanguageDocumento10 páginasFowler - Studying Literature As LanguageRocío FlaxAún no hay calificaciones

- Linguistic RepertoireDocumento7 páginasLinguistic RepertoireSumanth .sAún no hay calificaciones

- Towards Sociohistorical Analysis of Ancient GreekDocumento12 páginasTowards Sociohistorical Analysis of Ancient GreekEvangelosAún no hay calificaciones

- (C. K. Ogden, I. A. Richards) The Meaning of MeaningDocumento387 páginas(C. K. Ogden, I. A. Richards) The Meaning of MeaningAdrian Nathan West100% (6)

- Critical Applied Linguistics and EducationDocumento9 páginasCritical Applied Linguistics and EducationGustavo PinheiroAún no hay calificaciones

- Approaches To CDADocumento9 páginasApproaches To CDAHaroon AslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Lectura. Swales Chapter. 3Documento8 páginasLectura. Swales Chapter. 3Elena Denisa CioinacAún no hay calificaciones

- Geeaerts Decontextualising and Recontextualising Tendencies...Documento13 páginasGeeaerts Decontextualising and Recontextualising Tendencies...Angela ZenonAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse and Social Change by Norman Fairclough PDFDocumento135 páginasDiscourse and Social Change by Norman Fairclough PDFHerbert Rodrigues80% (10)

- Communicative Competence, Context and Context of Situation (Lecture 2)Documento5 páginasCommunicative Competence, Context and Context of Situation (Lecture 2)Joseph ArkoAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse Analysis and Second Language Writing - Wennerstrom Chap 01Documento16 páginasDiscourse Analysis and Second Language Writing - Wennerstrom Chap 01MohamshabanAún no hay calificaciones

- Ogden & Richards - 1946 - The Meaning of MeaningDocumento387 páginasOgden & Richards - 1946 - The Meaning of Meaningcezar_balasoiuAún no hay calificaciones

- The Sociology of Language An Interdisciplinary Social Science Approach To Language in Society by Joshua A. FishmanDocumento4 páginasThe Sociology of Language An Interdisciplinary Social Science Approach To Language in Society by Joshua A. FishmanultimategoonAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociolinguistics #1Documento19 páginasSociolinguistics #1IkramAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To Critical Discourse AnalysisDocumento20 páginasIntroduction To Critical Discourse AnalysisMehrul BalochAún no hay calificaciones

- Second Edition, Published by Elsevier, and The Attached Copy Is Provided by ElsevierDocumento14 páginasSecond Edition, Published by Elsevier, and The Attached Copy Is Provided by ElseviercaroldiasdsAún no hay calificaciones

- Linguistic Ideologies Text Regulation and The Question of Post-StructuralismDocumento32 páginasLinguistic Ideologies Text Regulation and The Question of Post-StructuralismchankarunaAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To StylisticsDocumento6 páginasIntroduction To StylisticsShaun TorresAún no hay calificaciones

- Lecture 1Documento5 páginasLecture 1vkolosiuckAún no hay calificaciones

- Ahearn 11 15Documento5 páginasAhearn 11 15Augusto QuetglasAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse GenresDocumento20 páginasDiscourse Genreslumendes79100% (1)

- What Is Language For Sociolinguists? The Variationist, Ethnographic, and Conversation-Analytic Ontolo-Gies of LanguageDocumento17 páginasWhat Is Language For Sociolinguists? The Variationist, Ethnographic, and Conversation-Analytic Ontolo-Gies of LanguageHammouddou ElhoucineAún no hay calificaciones

- Poststructuralism and Its Challenges For Applied LinguisticsDocumento10 páginasPoststructuralism and Its Challenges For Applied LinguisticsMilkii SeenaaAún no hay calificaciones

- Speech in Human Communities and Their Meanings To Those Who Use ThemDocumento2 páginasSpeech in Human Communities and Their Meanings To Those Who Use ThemSandra Streignard0% (1)

- Stylistics Retrospect and ProspectDocumento12 páginasStylistics Retrospect and ProspectKhalidAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Discourse AnalysisDocumento11 páginasCritical Discourse AnalysisErick E.EspielAún no hay calificaciones

- The Resurgence of Metaphor Review of andDocumento16 páginasThe Resurgence of Metaphor Review of andZhao YinqiAún no hay calificaciones

- Arts of ResistanceDocumento19 páginasArts of ResistanceMohd FarhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Theoretical TrajectoryDocumento8 páginasTheoretical TrajectoryZivagoAún no hay calificaciones

- Duranti-Language As CultureDocumento26 páginasDuranti-Language As CulturecamilleAún no hay calificaciones

- Language IdeologiesDocumento22 páginasLanguage IdeologiesGretel TelloAún no hay calificaciones

- Language and Culture Part 3 End D.Hymes C.KramchsDocumento2 páginasLanguage and Culture Part 3 End D.Hymes C.KramchsAmina Ait SaiAún no hay calificaciones

- STYLISTICS Material For Introduction To Linguistic ClassDocumento8 páginasSTYLISTICS Material For Introduction To Linguistic ClassRochelle PrieteAún no hay calificaciones

- The Cultural Component of Language TeachingDocumento10 páginasThe Cultural Component of Language TeachingelisapnAún no hay calificaciones

- Discourse and Critique Part One IntroducDocumento8 páginasDiscourse and Critique Part One Introducnatalie_goesAún no hay calificaciones

- Tagliamonte - Introduction PDFDocumento17 páginasTagliamonte - Introduction PDFAide Paola RíosAún no hay calificaciones

- Manifesto 1Documento12 páginasManifesto 1Nancy HenakuAún no hay calificaciones

- Woolard Language VariationDocumento12 páginasWoolard Language VariationArturo DíazAún no hay calificaciones

- An Introduction To Sociolinguistics. 4th Edition.:an Introduction To Sociolinguistics. 4th EditionDocumento4 páginasAn Introduction To Sociolinguistics. 4th Edition.:an Introduction To Sociolinguistics. 4th Editiongoli100% (1)

- Ergun Bridging Across Feminist Translation andDocumento12 páginasErgun Bridging Across Feminist Translation andMarília LeiteAún no hay calificaciones

- What Linguists Need From The Social SciencesDocumento7 páginasWhat Linguists Need From The Social SciencesQueen AiAún no hay calificaciones

- Halliday-Language As Social SemioticDocumento4 páginasHalliday-Language As Social SemioticKarin EstefAún no hay calificaciones

- Resources For Teachers and Students: A New Adventures ProductionDocumento33 páginasResources For Teachers and Students: A New Adventures ProductionSílvia MônicaAún no hay calificaciones

- 12 - Translingual Entanglements - PENNYCOOK - 2020Documento14 páginas12 - Translingual Entanglements - PENNYCOOK - 2020Sílvia MônicaAún no hay calificaciones

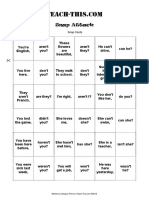

- Snap AttackDocumento3 páginasSnap AttackSílvia MônicaAún no hay calificaciones

- 3739 Wanted PosterDocumento1 página3739 Wanted PosterSílvia MônicaAún no hay calificaciones

- Audio AmplifiersDocumento11 páginasAudio AmplifiersWaqas AbroAún no hay calificaciones

- Electrical Diagrams and Operation Manual: As500Fue-1 Three Phase Control Box RetrofitDocumento66 páginasElectrical Diagrams and Operation Manual: As500Fue-1 Three Phase Control Box RetrofitalejandraAún no hay calificaciones

- L296Documento23 páginasL296billy_lxAún no hay calificaciones

- Self Assessment ReportDocumento104 páginasSelf Assessment ReportAsmatullah KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- DTE Imp QuestionsDocumento2 páginasDTE Imp QuestionsPushkar rane 1oth,B,ROLL NO.47Aún no hay calificaciones

- Microwind v35Documento130 páginasMicrowind v3510679488g0% (1)

- Classification On Basis of FabricationDocumento4 páginasClassification On Basis of FabricationMelkamu FekaduAún no hay calificaciones

- Project InverterDocumento67 páginasProject InverterKeshavGargAún no hay calificaciones

- EDI LAb ManualDocumento33 páginasEDI LAb ManualMadangle JungleAún no hay calificaciones

- Room Automation Using Bluetooth and WifiDocumento50 páginasRoom Automation Using Bluetooth and WifiSamruddhi Sandip kangudeAún no hay calificaciones

- EN-eng 12A1 Breaker-Control-Configuration-Gen-CbDocumento9 páginasEN-eng 12A1 Breaker-Control-Configuration-Gen-CbSreepriodas RoyAún no hay calificaciones

- CPS Module1 Notes by Chidanand S Kusur CSE DeptDocumento19 páginasCPS Module1 Notes by Chidanand S Kusur CSE DeptShariqa FatimaAún no hay calificaciones

- D TS ComRepDocumento259 páginasD TS ComRepihackn3wtonAún no hay calificaciones

- Time Table2013 PDFDocumento55 páginasTime Table2013 PDFbalan dineshAún no hay calificaciones

- Physics Project CBSE CLASS XII LOGIC GATES 2017Documento16 páginasPhysics Project CBSE CLASS XII LOGIC GATES 2017Jasmine James83% (12)

- Durag D-Ug 660Documento34 páginasDurag D-Ug 660Paulo80% (5)

- Build A Proton Precession MagnetometerDocumento14 páginasBuild A Proton Precession MagnetometerPedro J. Mancilla50% (2)

- PLC Project ReportDocumento18 páginasPLC Project ReportMayowaAún no hay calificaciones

- Experiment #1 Audio MonitorDocumento7 páginasExperiment #1 Audio MonitorDaniel CafuAún no hay calificaciones

- Triac Application NoteDocumento10 páginasTriac Application Notewizardgrt1Aún no hay calificaciones

- DEL Lab Manual - Experiment 8Documento6 páginasDEL Lab Manual - Experiment 8sara michikoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ec2404 Set2Documento6 páginasEc2404 Set2LAKSHMIAún no hay calificaciones

- ThereminDocumento18 páginasThereminzeljkokerumAún no hay calificaciones

- Contents For 3rd Sem and 4th Sem ECEDocumento28 páginasContents For 3rd Sem and 4th Sem ECEjchikeshAún no hay calificaciones

- Boost 1channel White Led Driver For Large LCDS: DatasheetDocumento42 páginasBoost 1channel White Led Driver For Large LCDS: DatasheetkanakAún no hay calificaciones

- TV Sharp 19K-M100 DiagramaDocumento36 páginasTV Sharp 19K-M100 DiagramaJomasando10100% (1)

- Conclusion PDFDocumento3 páginasConclusion PDFNilAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is The Main Difference Between Electrical and ElectronicsDocumento4 páginasWhat Is The Main Difference Between Electrical and ElectronicsAmbuj MauryaAún no hay calificaciones

- Digital Arithmetic: Combinational LogicDocumento3 páginasDigital Arithmetic: Combinational LogicJoseGarciaRuizAún no hay calificaciones