Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Emerging Markets and Blue Ocean Strategy

Cargado por

kalyan1234560 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

463 vistas0 páginasTurbulent times have hit both OECD and emerging country economies. Many businesses are seeking opportunities in new geographies. Companies can further extend or stretch their markets through the creative application of Blue Ocean strategies.

Descripción original:

Derechos de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoTurbulent times have hit both OECD and emerging country economies. Many businesses are seeking opportunities in new geographies. Companies can further extend or stretch their markets through the creative application of Blue Ocean strategies.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

463 vistas0 páginasEmerging Markets and Blue Ocean Strategy

Cargado por

kalyan123456Turbulent times have hit both OECD and emerging country economies. Many businesses are seeking opportunities in new geographies. Companies can further extend or stretch their markets through the creative application of Blue Ocean strategies.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 0

14 www.scip.

org Competitive Intelligence

Turbulent times have hit both Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and

emerging country economies. Deceleration in growth rates

of gross domestic product (GDP), consumer expenditure,

and international trade has put corporate earnings into a

tailspin. At the same time, the competition for a share of the

consumers wallet is becoming more severe. In Chan Kim and

Renee Mauborgnes parlance, the Red Ocean is becoming

bloodier (Borengaser/Jenkins 2008).

With competition in existing markets (Red Ocean)

becoming more intense, many businesses are seeking

opportunities in new geographies. Emerging markets such

as China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and others do provide

opportunities. Nonetheless even these markets have limited

white space, as local firms and the early-bird multinationals

are already safely ensconced there. This limits the scope of

arbitrage opportunities through geographical extension in

emerging economies.

Additionally, the emerging countries are increasing their

connections with the OECD economies. Strong linkages

exist in terms of capital flows, investment, and trade. The

impact of the international meltdown also affects emerging

economies such as India, China, Indonesia, Brazil, and

Mexico. Yet to some extent, many of these countries have

large domestic markets that are insulated from external chaos.

Companies can further extend or stretch their markets in

many product fields through the creative application of Blue

Ocean strategies.

COMPETITION PARADIGMS

The question that resonates across economies and

industries is how to build unassailable value innovations

which create new customers for specific product groups or

services. Entrepreneurs have grappled with this issue for

decades before the arrival of the stylized concept of Blue

Ocean.

The current competition paradigms, such as structure

conduct performance, five forces model and Blue Ocean

strategy, base themselves largely on the experiences of

developed countries. Several questions need to be answered

within the context of emerging economies:

How often do firms identify Blue Ocean opportunities

in emerging economies?

What is the nature of its value innovation?

How sustainable is the proposition?

EXAMPLE: LAUNDRY SOAPS AND DETERGENTS

In the early seventies, the Indian fabric wash market

was divided into two distinct categories, laundry soaps and

detergents. Laundry soap prices and quality fluctuated based

on current vegetable oil and fat prices, and the laundry soap

market was largely fragmented. The detergents market, which

could be further sub-divided into bars and powders, was

evolving. Initially the Indian subsidiary of Unilever was the

dominant player in this market.

In 1969, a small scale entrepreneur started detergent

powder production in his backyard. He priced his brand,

Nirma, at around one third the average retail price and at

75% of the quality level of existing detergent powders. This

product acquired a perceptible market size by the beginning

of the 1980s. Further, he created intensive distribution

networks in the Western Indian region where he was located.

He had lower capital costs, as his manufacturing process

did not use a blowing tower like other large scale detergent

manufacturers. A greater dependence on soda ash in the

By Siddhartha Roy, Tata Group

Emerging

Markets and Blue

Ocean Strategy

Volume 13 Number 1 January/March 2010 www.scip.org 15

product formulation enabled him to keep the material costs

low. Consumers accepted the level of product performance,

although the product was harsh on hands in bucket wash

situations.

The Nirma brand developed a strong clientele amongst

households at the lower end of the income pyramid. By

the mid-1980s it gained about 30% share of the detergent

powder market. Emboldened by this success, in 1987 he also

launched a detergent bar.

To counter Nirmas market penetration, the Indian

subsidiary of Unilever launched a brand called Wheel

which matched Nirma in most of the elements of cost and

business systems. To do this the company had to move

away from capital intensive blowing tower technology and

deliver a product formulation that would provide superior

performance at a matching cost.

Furthermore, the Wheel brand had to be supported by

a focused communication and branding exercise to carve out

a decent tonnage for itself. The bulk of this tonnage gain did

not come from market share gains within detergent powders,

but the major factor was market expansion: former non-

consumers of detergent powders (most were laundry soap

users) became detergent powder users. Within the overall

fabric wash category detergent powders substituted laundry

soaps.

In the early years a significant part of Wheels growth

came from laundry soaps. Marketing efforts carried out

by the two competitors, Nirma and Wheel, led to overall

detergents market expansion. Consequently, in the fabric

wash market laundry soaps tonnage started declining as soap

users, particularly those in the lower income groups, were

converted into customers of detergents. This value innovation

and development of new customers makes the Nirma-Wheel

saga an useful example of Blue Ocean strategy.

EXAMPLE: SHAMPOO PACKAGING

In the early 1990s Indian hair care market, the

government considered shampoos a luxury product and

subjected them to a 120% excise duty. Consequently, the

price of a 200 ml bottle was much higher than the daily wage

of an industrial worker.

In the mid-1980s, an innovative small-scale

entrepreneur in South India introduced a single-use shampoo

sachet at a very low unit cost. The packaging was a major

value innovation in terms of affordability and price point. It

sharply increased the customer base for shampoo as the focus

on unit value significantly helped in converting non-users

into customers. All the organized players and multinationals

followed suit and the shampoo market growth exploded,

further aided by the governments lowering of excise duties on

the product. Towards the end of the 1990s, the sachet market

segment held more than two thirds of the total shampoo

market.

In each of these two cases value innovations driven by

small scale entrepreneurs brought about a structural change

in the markets. The demand curve shifted to the right, and

the average price point dropped significantly.

An interesting aspect of emerging market economies

is that demographic as well as economic growth leads to

market expansion. Markets in these economies grow when

more people are using the product (penetration growth) or

through increase in usage (quantity used per capita goes up).

Normally, penetration growth of a product category in an

emerging economy like China, Brazil, South Africa, or India

is faster than the increase in the usage depth. Consequently,

several players have the space to grow for several years. This is

an issue worth pondering over. The first principle of the Blue

Ocean strategy is to reconstruct market boundaries to break

from competition and create blue oceans.

Barring toilet soaps and detergents (which have 90%

penetration rate), many personal care products have much

lower customer percentages, even in urban India. For

example, for color cosmetics it is 22%, deodorants 9%, and

diapers 2%. In the rural areas where purchasing power and

media exposure are limited, usership is lower than urban

areas.

As the income, education and media exposure grows,

consumer levels go up in urban as well as rural markets. Over

six per cent per capita income growth in the last five years

have accelerated this expansion, but the average quantity

used per household or person increases rather slowly. From

the blue ocean strategy point of view, the key is to use value

innovation which can expand the contours of the market in

the low usership areas and amongst non-users located in the

smaller towns and rural India.

EXAMPLE: AUTOMOBILE SECTOR

One of the key tenets of Blue Ocean strategy is to avoid

head-to-head competition and look for blue oceans through

market reconstruction. This effort targets new customers by

looking across alternative industries, and different strategic

groups within an industry.

Take the automobile industry for example, with

established categories in terms of price and performance such

as the luxury segment, economy segment which includes

small cars and compacts, etc. Usually no company attempts

to create a discontinuity in terms of the price performance

relationship or the way a segment is normally defined. Herein

lies the opportunity of creating a blue ocean.

Another cornerstone is value innovation. In the value/

price trade-off, blue ocean strategy differs from traditional

competitiveness strategy. Traditional strategy focuses on the

trade-off between creating greater value (differentiation) at

a relatively high cost, or providing reasonable value at a low

cost. The idea behind blue ocean strategy is to provide both

at the same time.

emerging markets and blue ocean strategy

16 www.scip.org Competitive Intelligence

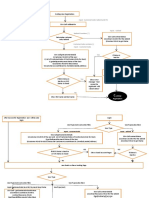

Blue ocean strategy provides a framework for initiating

four types of action which identify:

Factors that the industry takes for granted but can be

eliminated.

Factors that can be reduced.

Where the value offerings should be raised.

Which new factors to create that increase the value

offerings.

In a blue ocean strategy one restricts consumer choice

by either eliminating or reducing certain product offerings

on one hand, and on the other certain offerings are either

Tata Nano (passenger car)

Targeted new customers:

Upgrade two wheeler (i.e. motor cycle and scooter) users into a four wheeler user.

Upgrading can provide a huge opportunity (passenger car market in India is 1.2M, two wheeler sales are 7.4M).

Nature of value innovation:

Spacious, passenger compartment for four adults.

Fuel efficiency highest for any petrol car in India (23.6 km./liter).

High fuel efficiency plus low curb weight equals very low level of emissions.

Safety test exceeds regulatory requirements.

Base model cost around $2,500.

Four Actions Framework for new value curve (based on eliminate-reduce-raise-create structure)

Standard model is a no frills car.

Comes in only three color options.

Focus on safety, fuel efficiency, and passenger comfort.

Best leg space comfort in the small car segment.

Upgraded features available in Nano CX and Nano LX.

Tata Ace (mini truck)

Targets new customers:

Attractive upgrade of three wheeler users into safer, more comfortable and easy-to -drive four wheel vehicle. (Priced around

$4,500.)

Customer upgrades provides huge opportunity (2005 total light commercial vehicle sales in India 200,000; three wheeler sales

350,000).

Fits into the increasing use of hub and spoke model in last-mile goods distribution.

Avoids potential government restrictions on the entry of heavy and medium trucks into cities during high-traffic hours.

Nature of value innovation:

Sized as a sub-one ton category vehicle. In densely populated urban areas, streets are narrow, requiring mini trucks with adequat

maneuverability. In rural areas they provide small producers connections to nearby urban markets.

One of the few mini trucks in the world with twin cylinder diesel engine.

Maintenance cost and running costs lower than three wheelers, which improves the rate of return for the operator.

Four Actions Framework: (based on eliminate-reduce-raise-create structure)

Not a long distance truck. Maximum speed higher than three wheelers but restricted to within 65 kms/hour.

Excellent turning radius allows easy maneuverability.

Combines mini truck reliability with car-like comfort in the drivers cabin.

Provides a platform for further product extension at both ends of the market: rural passenger and semi urban transport, and

specialist logistics.

increased or created. Put together, these four types of actions

create the eliminate-reduce-raise-create framework.

Keeping these in mind, lets examine two examples from

the automobile sector. The first is the Tata-Nano, a small

car which has already created ripples amongst automobile

enthusiasts around the world. The second example is the

small truck called Tata-Ace (see Sidebar).

Scaling up of these two vehicles has been very rapid.

More than 200,000 orders for Nano were placed during the

bookings period of April 9

th

through April 25

th

. Within two

years of its launch in 2005, 100,000 Ace vehicles have been

sold. In both cases, product differentiation coupled with cost

focus provides a sustainable competitive advantage.

SIDEBAR: TATA NANO AND TATA ACE

emerging markets and blue ocean strategy

Volume 13 Number 1 January/March 2010 www.scip.org 17

The high volume generation through value innovations

makes the strategic advantage more sustainable, as it places

imitators at a cost disadvantage. In addition, the technical

platform created by the mini truck Tata-Ace has been

extended indo developing two new products, Magic and

Winger. These multi-passenger commercial vehicles once

again take the company to a new value curve. Finally, the

value innovation of Tata Nano buttressed by media reporting

has created a brand buzz which imitators will find difficult to

counter both in the country and other geographies.

EXAMPLE: MICROFINANCE

Another example of making competition irrelevant is

the micro finance institutions working amongst the poor.

Traditional wisdom suggests bankers should avoid lending

to the rural poor in less developed and developing countries.

Until recently banks held the general belief that the business

of extending micro finance can never be a profitable activity.

Given the vast multitude of rural poor across geographies

this is clearly a large Blue Ocean. Bangladesh Grameen Bank

showed that once the bankers learn how to work with the

poor through microfinancing, they can develop increased

returns by harnessing hundreds of micro entrepreneurs.

The success of Grameen Phone, a mobile telephony joint

venture between Telenor and Grameen Bank, also emphasizes

this point. Extending mobile telephony use amongst previous

non-customers like farmers and fishermen in any country,

be it China, India or Indonesia requires an understanding

of which add-on service provides exceptional utility to these

customers and their acceptable price point. For example,

informing fishermen who are out in the sea about the prices

and landings in different ports or sending an early indication

about a shoal of fish based on satellite imagery can be of

immense commercial utility to them.

Obviously the companys cost structure will have to

be adjusted to meet the requirements of these customers.

This thought is very similar to the Blue Ocean Idea Index

suggested by Kim and Mauborgne sustainable competitive

advantage can only be derived by being increasingly useful to

the consumer. The Blue Ocean idea index has four essential

tenets:

utility to the consumer

affordable price

affordable cost to the manufacturer

ease of adaption

All four elements can be found in the telecom example

above. However, for a traditional telecom multinational,

adoption of these practices would require major cultural and

operational changes. Unless they are accomplished, it would

be very difficult to become a successful competitor in the

rural and semi-rural markets of the emerging countries.

The examples provided in this paper suggest that

businesses in emerging economies have already understood

the need for seeking out new target groups of consumers and

for expanding the market in order to survive and grow. These

businesses also identified which value innovations should

be included in their offerings. In most cases, differentiation

and cost focus have been combined, avoiding an either/or

situation.

Thirdly, through trial and error, entrepreneurs have also

determined which factors connected to their products or

services should be decreased or eliminated and which ones

should be increased or added de novo. The contribution of

Kim and Mauborgnes Blue Ocean strategy lies in providing

a theoretical structure and an analytical construct for the

empirical evidence. Viewed from that perspective, Kim and

Mauborgnes framework hopefully will enable lesser mortals

like strategy planners to develop the necessary business

insight which comes naturally to legendary entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Borengaser, Stephen; Jenkins, Anne (2008). Applying the

blue ocean strategy, Competitive Intelligence, July/

August, v11n4, p17-22.

Clayton, Christensen (1997). The Innovators Dilemma: When

New Technologies Caused Great Firms to Fail. Harvard

Business School Press, Boston.

Clayton, Christensen (2004). Seeing Whats Next, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston.

Hamel, Gary (1998). Opinion: strategy innovation and the

Quest for value, MIT Sloan Management Review.

Kim, Chan W; Mauborgne, Renee (2005). Blue Ocean

Strategy. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Porter, Michael E. (1988). Competitive Advantage, New York

Free Press.

Dr. Siddhartha Roy is Economic Advisor to the Tata Group.

He has nearly three decades of research and in-house consultancy

experience in the areas of competitive strategy, macro and

micro econometric modeling, strategic planning, country/

firm competitiveness studies, pricing research, new opportunity

identification, etc. Siddhartha has first hand knowledge of

the examples mentioned in the text; both as a midfield player

and also as a spectator on the sidelines. He can be contacted at

siddhartha_roy_in@yahoo.com.

emerging markets and blue ocean strategy

También podría gustarte

- Alice Schroeder Warren Buffett PDFDocumento21 páginasAlice Schroeder Warren Buffett PDFAhmad DamasantoAún no hay calificaciones

- Hobby & Toy Stores in The US Industry ReportDocumento37 páginasHobby & Toy Stores in The US Industry ReportOozax OozaxAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignments Consumer BehaviourDocumento5 páginasAssignments Consumer BehavioursweetMPP100% (1)

- Managing Britannia: Culture and Management in Modern BritainDe EverandManaging Britannia: Culture and Management in Modern BritainCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Sullivan Ford Auto WorldDocumento12 páginasSullivan Ford Auto WorldVignesh RV100% (2)

- Deepak ParekhDocumento42 páginasDeepak ParekhAbimanyu NNAún no hay calificaciones

- HiteVision Group2 Team06Documento5 páginasHiteVision Group2 Team06IIM Trichy Mohit VermaAún no hay calificaciones

- New Public ManagementDocumento12 páginasNew Public ManagementrahmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Psda 1: Amul: Pranjal Sharma 7 Shalini Agrawal 23 Aastha Singhi 12 Nancy Garg 51Documento26 páginasPsda 1: Amul: Pranjal Sharma 7 Shalini Agrawal 23 Aastha Singhi 12 Nancy Garg 51nancy100% (1)

- Case 6Documento3 páginasCase 6stella12345900% (1)

- Beauty More Than Skin Deep?: Case Study 7Documento15 páginasBeauty More Than Skin Deep?: Case Study 7Trần Hữu Kỳ DuyênAún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing of Services Assignment Dated 04-06-2020Documento2 páginasMarketing of Services Assignment Dated 04-06-2020RICHARD BAGEAún no hay calificaciones

- Cultural Norms, Fairness Creams & Advertising ImpactDocumento24 páginasCultural Norms, Fairness Creams & Advertising ImpactChirag Bhuva100% (2)

- Case 2 COO and Country Manager Job Selection Exercise KEEDocumento1 páginaCase 2 COO and Country Manager Job Selection Exercise KEEbamAún no hay calificaciones

- Quest MBA EnI Pragya Budhathoki Assignment IIDocumento8 páginasQuest MBA EnI Pragya Budhathoki Assignment IIpragya budhathokiAún no hay calificaciones

- Advertising - Glitter vs Reality/TITLEDocumento1 páginaAdvertising - Glitter vs Reality/TITLEHarsh AnchaliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Absolut Vodka Case StudyDocumento4 páginasAbsolut Vodka Case StudyKhushbooAún no hay calificaciones

- Strategic Management of Spice JetDocumento23 páginasStrategic Management of Spice JetSanhita DasAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Grp1 Bay MadisonDocumento11 páginasFinal Grp1 Bay MadisonDilip Thatti0% (1)

- SHRM Module 1Documento44 páginasSHRM Module 1Nikita Bangard100% (1)

- Stealth Marketing - Consumer BehaviourDocumento20 páginasStealth Marketing - Consumer BehaviourEric LopezAún no hay calificaciones

- GuthaliDocumento2 páginasGuthaliAvinash ChandraAún no hay calificaciones

- Case 2 Giovanni Buton (COMPLETE)Documento8 páginasCase 2 Giovanni Buton (COMPLETE)Austin Grace WeeAún no hay calificaciones

- MichlelinDocumento22 páginasMichlelinmoeedbaigAún no hay calificaciones

- Axis Bank - Case StudyDocumento4 páginasAxis Bank - Case StudyDeepshikha YadavAún no hay calificaciones

- FLATPEBBLEDocumento9 páginasFLATPEBBLERasika Dhiman100% (1)

- Final Presentation Rajesh ExportsDocumento20 páginasFinal Presentation Rajesh ExportsNikhlesh MatnaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study - The Case of The Un Balanced ScorecardDocumento15 páginasCase Study - The Case of The Un Balanced ScorecardNadia HarsaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Deep Change Referee ReportDocumento3 páginasDeep Change Referee ReportMadridista KroosAún no hay calificaciones

- Hindustan Unilever Limited and Monopolistic Competition in the Indian FMCG MarketDocumento2 páginasHindustan Unilever Limited and Monopolistic Competition in the Indian FMCG MarketAravind SunilAún no hay calificaciones

- Investment in Job SecureDocumento2 páginasInvestment in Job Securesajid bhatti100% (1)

- Summary of Case Study A New Approach To Contracts by Oliver Hart and David FrydlingerDocumento2 páginasSummary of Case Study A New Approach To Contracts by Oliver Hart and David FrydlingerYasi Eemo100% (1)

- Customer Value, Types and CLTVDocumento15 páginasCustomer Value, Types and CLTVSp Sps0% (1)

- HyundaiDocumento20 páginasHyundaiDeep BajwaAún no hay calificaciones

- Anne Mulcahy's Leadership Turns Around XeroxDocumento15 páginasAnne Mulcahy's Leadership Turns Around XeroxSandarsh SureshAún no hay calificaciones

- Corus Change Case Study PDFDocumento5 páginasCorus Change Case Study PDFblackwings060550% (2)

- Amul BethicsDocumento15 páginasAmul BethicsTeena VarmaAún no hay calificaciones

- HEC Project Report1Documento52 páginasHEC Project Report1r_bhushan62100% (1)

- Zipcar: Customer Driven MarketingDocumento2 páginasZipcar: Customer Driven MarketingMuhammad Abbas100% (1)

- Balbir PashaDocumento2 páginasBalbir PashaANUSHKAAún no hay calificaciones

- GuthaliDocumento4 páginasGuthaliJohnsey RoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Coca ColaDocumento64 páginasCoca ColaRachit JoshiAún no hay calificaciones

- 6b EPRG FrameworkDocumento2 páginas6b EPRG FrameworkNamrata SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- The Distribution Network of AmulDocumento9 páginasThe Distribution Network of Amulvj123456783% (6)

- L'Oreal of Paris - Q1Documento3 páginasL'Oreal of Paris - Q1rahul_jain_76Aún no hay calificaciones

- Leadership Change in DisneyDocumento6 páginasLeadership Change in DisneyumarzAún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing Research: Bay Madison IncDocumento12 páginasMarketing Research: Bay Madison IncpavanAún no hay calificaciones

- Distribution Challenges and Workable Solutions: Avinash G. MulkyDocumento17 páginasDistribution Challenges and Workable Solutions: Avinash G. MulkyNeilAún no hay calificaciones

- Customer Awareness With Respect To Asian PaintsDocumento103 páginasCustomer Awareness With Respect To Asian PaintssankritraiAún no hay calificaciones

- Recruitment and SelectionDocumento24 páginasRecruitment and SelectionMeena IyerAún no hay calificaciones

- AkilAfzal ZR2001040 FinalDocumento4 páginasAkilAfzal ZR2001040 FinalAkil AfzalAún no hay calificaciones

- Ions ConsultantDocumento15 páginasIons ConsultantAsep Kurnia0% (1)

- Project On Parle AgroDocumento40 páginasProject On Parle AgroFarhan BadakshaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Innovation Management-Paradise ParkDocumento12 páginasInnovation Management-Paradise ParkUjjwala Dalvi100% (1)

- Dongfeng Commercial Vehicle Company-EU Market Entry and DistributionDocumento7 páginasDongfeng Commercial Vehicle Company-EU Market Entry and DistributionRUCHITAún no hay calificaciones

- Natarajan ChandrasekaranDocumento2 páginasNatarajan ChandrasekaranNaganathan RajendranAún no hay calificaciones

- Reasons for Euro Disney's Early Failure and Disneyland Paris' TurnaroundDocumento3 páginasReasons for Euro Disney's Early Failure and Disneyland Paris' TurnaroundVishakajAún no hay calificaciones

- Training Development Report Index Table Contents Acme TelepowersDocumento40 páginasTraining Development Report Index Table Contents Acme TelepowersFaizan Billoo KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Ambrosia Catering ServicesDocumento8 páginasAmbrosia Catering Servicessarathipatel0% (1)

- BA1722 Services MarketingDocumento17 páginasBA1722 Services MarketingChandru SivaAún no hay calificaciones

- BorolineDocumento2 páginasBorolineRajaram RajagopalanAún no hay calificaciones

- Product Line Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionDe EverandProduct Line Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionAún no hay calificaciones

- Lease PaymentsDocumento62 páginasLease PaymentsWinda NurmaliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lease PaymentsDocumento2 páginasLease Paymentskalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- FY15 Tax Graduate Development ProgramDocumento27 páginasFY15 Tax Graduate Development Programkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- AccountingggDocumento16 páginasAccountingggkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- Pa FCDocumento4 páginasPa FCkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- Is your insurance complaint unheard? Contact IRDA for helpDocumento10 páginasIs your insurance complaint unheard? Contact IRDA for helpvinaysekharAún no hay calificaciones

- FDDocumento2 páginasFDkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- AirportDocumento39 páginasAirportkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- 567 1691 1 PBDocumento3 páginas567 1691 1 PBkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- Blue OceanDocumento5 páginasBlue OceanankitpnaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Securities and Exchange Board of India Recruitment of Officer Grade A (Legal) - On ContractDocumento4 páginasSecurities and Exchange Board of India Recruitment of Officer Grade A (Legal) - On Contractkalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sector of The EconomyDocumento5 páginasSector of The EconomyAnubhav ChatterjeeAún no hay calificaciones

- 100 Most Commonly Asked One Word SubstitutesDocumento4 páginas100 Most Commonly Asked One Word Substituteskalyan123456100% (1)

- IIFT GK Question BankDocumento7 páginasIIFT GK Question BankAmit GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- RBI Grade B Cut Off Marks 2011Documento1 páginaRBI Grade B Cut Off Marks 2011kalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- CV Writing TipsDocumento6 páginasCV Writing TipsSherwan R Shal100% (15)

- Topic andTOC-Synon BookDocumento7 páginasTopic andTOC-Synon BooktikbalangAún no hay calificaciones

- Customer HierarchyDocumento3 páginasCustomer Hierarchykalyan123456Aún no hay calificaciones

- Government Budget: Objectives, Components, and Impact on the EconomyDocumento17 páginasGovernment Budget: Objectives, Components, and Impact on the EconomyHeer SirwaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethiopian Education Development Roadmap 2018-2030Documento101 páginasEthiopian Education Development Roadmap 2018-2030amenu_bizuneh100% (2)

- TechSci Research IndiaDocumento24 páginasTechSci Research Indiaธนวรรธน์ จันทระAún no hay calificaciones

- Preface: Social Protection For Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento2 páginasPreface: Social Protection For Sustainable DevelopmentUNDP World Centre for Sustainable DevelopmentAún no hay calificaciones

- Brazil Beauty SectorDocumento36 páginasBrazil Beauty SectorJosé Eduardo Amaral RodriguesAún no hay calificaciones

- Divya Jaiswal 1904 A71318219001 B.A. (H) Economics, Sem-4 2019-2022 Book ReviewDocumento4 páginasDivya Jaiswal 1904 A71318219001 B.A. (H) Economics, Sem-4 2019-2022 Book ReviewfrootiAún no hay calificaciones

- GX Us Consulting Turningthepage 06212012Documento12 páginasGX Us Consulting Turningthepage 06212012J NarenAún no hay calificaciones

- RLB International Report First Quarter 2015Documento60 páginasRLB International Report First Quarter 2015Nguyen Hoang TuanAún no hay calificaciones

- Aregay Editd ProposalDocumento25 páginasAregay Editd ProposalFasiko AsmaroAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study On Subway Customer Loyalty and Evaluating Marketing Strategies PDFDocumento14 páginasCase Study On Subway Customer Loyalty and Evaluating Marketing Strategies PDFOmer FarooqAún no hay calificaciones

- Econ 2Hh3: Intermediate Macroeconomics II: Winter 2021 Bettina Brüggemann & Marc-André LetendreDocumento41 páginasEcon 2Hh3: Intermediate Macroeconomics II: Winter 2021 Bettina Brüggemann & Marc-André LetendreYONG ZHOUAún no hay calificaciones

- Jurnal Teori SkrispsiDocumento8 páginasJurnal Teori SkrispsiApri Tauarz Tb-tenAún no hay calificaciones

- Mozambique-Annual-Report - ONUDocumento33 páginasMozambique-Annual-Report - ONUMaria RaposoAún no hay calificaciones

- EOGEPL Annual Report 2017 18 CompressedDocumento96 páginasEOGEPL Annual Report 2017 18 CompressedG Vishwanath ReddyAún no hay calificaciones

- A New Economic Agenda For Nevada - Final ReportDocumento233 páginasA New Economic Agenda For Nevada - Final ReportRiley SnyderAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review On Manufacturing Sector in NigeriaDocumento4 páginasLiterature Review On Manufacturing Sector in NigeriaafdtrajxqAún no hay calificaciones

- Assessment On Opportunities Gaps and Challenges On Land Based Investment in Oromia RegionDocumento41 páginasAssessment On Opportunities Gaps and Challenges On Land Based Investment in Oromia RegionDejeneAún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing Environmental Analysis A StudyDocumento30 páginasMarketing Environmental Analysis A StudyAmdework100% (1)

- Globalization's Impact on the Indian EconomyDocumento95 páginasGlobalization's Impact on the Indian EconomyZoya ShabbirhusainAún no hay calificaciones

- Vol. 12 No. 2 OpatijaDocumento150 páginasVol. 12 No. 2 Opatijagr3atAún no hay calificaciones

- A New Model For Online Food Ordering Service Based On Social Needs in A Sharing EconomyDocumento13 páginasA New Model For Online Food Ordering Service Based On Social Needs in A Sharing EconomyAnonymous NSBhi9z5WAún no hay calificaciones

- Rapport Retail Vision 2025Documento52 páginasRapport Retail Vision 2025Anonymous Hnv6u54HAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/RJFA Vol.10, No.3, 2019Documento12 páginasResearch Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/RJFA Vol.10, No.3, 2019daniel nugusieAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter One Entrepreneurship and Free Enterprise 1.0: 1 SINTAYEHU TESSEMA:sintetessema@gamail, ComDocumento23 páginasChapter One Entrepreneurship and Free Enterprise 1.0: 1 SINTAYEHU TESSEMA:sintetessema@gamail, Comhabtamu tadesseAún no hay calificaciones

- Mediterranean Port GrowthDocumento10 páginasMediterranean Port GrowthBert CappuynsAún no hay calificaciones

- Cambridge Learner Guide For Igcse Economics PDFDocumento21 páginasCambridge Learner Guide For Igcse Economics PDFaymanbkcAún no hay calificaciones

- EC112 Bonus Paper 1Documento2 páginasEC112 Bonus Paper 1BRIAN GODWIN LIMAún no hay calificaciones