Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

COPYRIGHT FOR DIRECTORS - EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF DIRETCORS - FERA-Presentation-The-7-Cs-of-Copyright1 PDF

Cargado por

Spiro N. TaravirasTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

COPYRIGHT FOR DIRECTORS - EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF DIRETCORS - FERA-Presentation-The-7-Cs-of-Copyright1 PDF

Cargado por

Spiro N. TaravirasCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Presentation at the European Parliament Copyright Working Group meeting January 12, 2011

#$%!&!!'(!)*!+),-./0$1!

Introduction The concept of European cinema - our collective audiovisual heritage - enjoys a unique position as a point of reference in all four corners of the world. The canon of works bears the hallmarks of quality and innovation, as achieved by master directors during the century that has passed since Europe invented the 7th art. Audiovisual works naturally tend to cross national borders and transcend their cultural origin. And filmmakers have always been highly mobile, driven by curiosity to portray human experience in its many manifestations across the globe. French film director Robert Bresson said: Make visible what, without you, might perhaps never have been seen. Many directors identify with this credo when explaining their choice of profession. What is made visible is the directors artistic vision that defines how the story is told; and the very purpose of making the film is to share this vision with an audience. As a result some viewers may even end up seeing the world in a new or different way. In speaking about copyright from the artists point of view, I would like to share my vision as a film director of what copyright stands for, and how it affects my daily work. I will also point out current practices that I believe undermine the spirit and intention of most copyright laws. Today many seem to have a perception of copyright in which the

! represents:

Corporate greed Multi-national corporations that do not give the creators and artists their fair share of earnings. Consumer constraints Old business models that limit access to works by territory and by a pre-imposed chronology of release windows. Collective management societies Sometimes lacking either democracy, transparency or efficiency.

"!

It is my claim that these are all problems of how copyright is exercised and not problems of copyright laws themselves. Yet some stakeholders promote such a view of copyright because they have a vested interest in undermining copyright legislation, and seek a reform that is financially lucrative to them. I urge you to examine their motives before changing copyright at the expense of the creators it was designed to protect. So what I would like to make visible today is what I see as the core values of copyright. I will call them the 7 Cs of copyright:

1. !REATORS RIGHTS These days it seems like the consequences of the digital revolution cannot be overstated, but while many things have changed and will change, what does not is the fact that films are made by filmmakers. Although we use the word copyright for short, what we are talking about in the European tradition are authors rights. Authors rights reflect the fact that people, rather than corporations, create works, and are premised on the principle that the fruits of intellectual labours are the property of their creators. In his 2004 report Creators and Copyright in Canada1 journalist John Lorinc sums up the important conceptual difference between the two: Droit dauteur makes each creator an entrepreneur of the mind, while copyright makes each creator a labourer.

2. !REATIVE FREEDOM Moral rights are meant to protect the human beings who have created the work, as opposed to those who finance or commission the creation of that work. The justification of moral rights comes from the notion that the work incorporates the personality of the author. Moral rights are inalienable - they are personal to the author, and can neither be transferred to third parties nor relinquished altogether, though unfortunately in some legislations (e.g. the UK) they can be waived by contract. The history of film shows that the best films are made when directors are afforded conditions that enable them to pursue their vision and develop as artists. Yet it is becoming a habit to deny the artists who work in the film industry their creative rights. Many producers, distributors and commissioning editors want to interfere in the creative process and assert final cut authority on the film, often as a non-negotiable term in the contract, claiming competence on what the audience wants and pointing to their financial responsibilities. Today economic pressure also results in ever more intrusive commercial breaks and product placement. On TV, station logos are superimposed ruining the carefully composed framing of each picture in the film, aspect ratios are distorted, and the credits are often cut off, or made

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! "!+)33/((/)4%5!6-!+.%71).('!+),-./0$1!+)78/1/)49!+7475/74!8%0/(871/)4!/(!7!$-6./5!6%1:%%4!1$%!1:)9! ! 2!

to run faster, or they are reduced on a split screen while the channel trailers the following program. This violates directors moral rights, alienates audiences and destroys the film experience. And these practices, caused by dependence on advertising revenue, have also migrated to the Internet. As the user blue_beetle wrote on the MetaFilter weblog: If you are not paying for it, youre not the customer; youre the product being sold. Many, including young people, who are actually willing to pay for our works, cannot find an easy way to do so because they do not own a credit card. FERA calls for the creation of a unified European micropayment infrastructure for online use, as an urgently needed alternative to advertisement-based business models.

3. !ASH Remuneration Today many directors find themselves at the bottom of the food chain in the audiovisual industry, struggling for reasonable working conditions and fair remuneration. The terms generally offered to directors today do not adequately reflect the directors role and responsibility, or respect the moral and economic rights of authors that copyright legislation actually provides for. Legal remuneration rights for directors vary enormously from country to country, despite some favourable EU legislation in recent years. The creation at the European level of an unwaivable right to remuneration for the online exploitation of audiovisual authors works was listed among possible EU actions foreseen by the 2009 Reflection Document from the European Commission. This is an action that FERA strongly favours. The unwaivable right to remuneration should also include revenues generated by online exploitation and paid by the final commercial user (the online platforms), and administered by collective management societies with the highest levels of governance and transparency.

4. !ONTINUITY Funding of Production For a vibrant audiovisual industry to exist, there must first be talented individuals who create. These talents must be identified and nurtured from an early age, and given the opportunity to take creative risks and hone their skills. The challenge is to then keep that talent working, developing a career and fulfilling their potential. But across Europe, the directors impetus to excel creatively is under pressure from dwindling budgets and tighter film schedules.

;!

In a recent survey among European companies in the cultural and creative industries, the findings show that 60% are micro-companies with only 1-3 employees, and that they put up 70% of the financing of their own activities by investing their salaries, private loans, money earned doing other work. (I have myself done all of this). They received only 15% public funding, and must find the rest through various other sources. This is a constant challenge because investing in culture is considered high risk. In spite of this, the economic growth in the cultural sector is 3 times higher than in other industries. When asked what was needed to make a critical step forward, the single answer was, Access to more real funding. At the moment the digital shift has far greater consequences for the audiovisual sector compared to other related sectors, as it seems to require a fundamental restructuring of the industrys financial mechanisms. Just as the audiovisual industry finds itself in a state of transition from old business models to new ones, the global financial crisis has caused member states to cut state aid to production of new films, broadcasters to pay less for screening rights, corporate sponsorship to decrease sharply, and private investors to invest more conservatively - if at all. FERA believes in the principle that all who profit from audiovisual works should contribute financially to the development and production of new works. This must include Internet service providers (ISPs) and online platforms and services for audiovisual content (as provided for in Article 3i of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive). And any online Europe-wide or multi-territory license must not destabilize the very sector specific system of financing films and television programmes, without providing alternative production funding sources. There is a serious funding gap that must be breeched. Google, for instance, made the leap from digital librarian to merchant a few weeks ago, and according to reports, stands to get 20%-30% of the price of eBooks. Audiovisual content is surely next in line. As Google steps directly into the value chain it would only be reasonable that they make a contribution to production funding.

5. !OLLABORATION ON FAIR TERMS Intermediaries In her speech A Digital World of Opportunities at the Avignon Forum in November Commissioner Kroes stated: Like it or not, content gatekeepers risk being sidelined if they do not adapt to the needs of both creators and consumers of cultural goods. So who will win the heart of the creators and of the public? The film directors answer to this is very simple: Those who finance our work, distribute our films as widely as possible, and pay us fairly for their use. Right now that can only be the traditional players. Online distribution currently produces little revenue. We are open to new partnerships if they offer a better strategy but it has to be one that actually works. In the online environment the threat to the director is not only piracy, but also obscurity in the massive information flow sifted by search engines based on commercial interests.

!

The current system is rather like a reverse game of musical chairs, where a new chair is

<!

added to the revenue split each time the music stops. If the digital age is to be truly revolutionary to us, the filmmakers, it must result in fewer chairs, and a direct access to our audiences. Contract law Granting new and improved rights to directors on a Europe wide basis is essential, but not enough. These rights must be inalienable. And they must be achievable. If directors are to receive fair remuneration for all forms of exploitation of their works - there is a growing need to strengthen their contractual position. Frequently when a director comes to the point of signing the contract, the power of the producer and the current demands of the market players, paradoxically deprives him or her of the benefit of well-intentioned laws. In many European countries the directors only remuneration derives from the initial contract with the producer, with no payments being made for subsequent use even for a profitable release. This cannot be allowed to continue. The scope of rights granted to the producer varies from one Member State to the other. The concept of cessio legis (whereby the law automatically places all economic rights with the film producer), as practiced in countries such as Austria, should be abolished. The 2002 amendment to the German Copyright Act for the purpose of strengthening the contractual positions of authors and performers was a bold move by legislators who recognised that freedom of contract is illusory when the parties signing an agreement have grossly disproportionate economic strength. This is an example to be promoted and enforced at the European level.

!

A crucial feature of any contract in the field of copyright is clarity in the ownership of rights. To ensure that rights are exploited in the best possible way, we believe they should be licensed and not assigned. An assignment is a transfer of a property right. So if all rights are assigned, the person/company to whom the rights were assigned becomes the new owner of copyright. In some countries, an outright assignment of copyright is not legally possible, and only licensing is allowed. Licensing means that the owner of the copyright retains ownership but authorizes a third party to carry out certain acts covered by his economic rights, generally for a specific period of time and for a specific purpose.

It is our view that the EU legislators should define a set of compulsory conditions pertaining to authors rights contracts to be harmonized in European contract law. . These harmonized conditions could be to: Presume the authors first ownership of copyright also where a work is created in the course of employment or on commission, unless expressly agreed otherwise; Require that rights can only be licensed, not assigned, and that licensing only be valid if put down in writing and include the all terms/conditions as agreed between the parties; A directors rights may be licensed singly, in groups, or all at once, but each right or group of rights, term and payment must be specified in the contract;

=!

Any right not specifically licensed by name is retained; Require the exercise of any right to be specific as to extent, purpose, place and duration; Prohibit the licensing of rights that cover exploitation by means not known or reasonably foreseeable; where national legislation might permit this the contract should be carefully framed to exclude it; Allow licensing of rights in future works only under certain conditions; Allow rights to revert to authors if unused or no longer used; Prohibit sub-licensing of rights without the creators consent; Require any waiver of moral rights to be delineated explicitly in writing; Require any rights of equitable remuneration to be inalienable, and to be not only unassignable but unwaivable; Specify that substantial breach of contract cause reversion of rights to the creator (for example in instances where a producer fails to give the creator access to accounts and sales reports).

In 2010 FERA began the process of establishing European film directors Contract Guidelines, to be followed by a system of FERA Approval of acceptable contracts, in an effort to educate our members about their rights. We do, however, need legislators to protect and improve these legal rights when they do not achieve the desired results in real life.

6. !ONSEQUENCES Enforcement All directors naturally want the largest possible audience for their films and welcome the possibilities that the digital shift offers in making their films available to new audiences. But they also need fair remuneration to support themselves, especially in the initial stages of new creative work. Online copyright infringement (piracy) is more rampant than ever and has taken on massive commercial dimensions. This severely affects the return on investments by the players in the value chain, and hampers the further development of attractive legal offers. Such violations must be dealt with urgently and decisively by law enforcement and at the political level, nationally and internationally. And while plenty can be said about creators not getting a fair share of the revenue from their work, those who justify ripping off the copyright industry because the artists and filmmakers arent getting the money anyway, are missing the point: 10% of something is a whole lot better than 100% of nothing.

! !

7. !REATOR-CONSUMER PARTNERSHIP In a time when our works are circulated in an intangible format, it is even more important to underline that what is being paid for by the consumer is not the piece of plastic that the film is stored on, but the creative efforts of the filmmakers and the costs of promoting and distributing that work as widely as possible.

>!

When it comes to online distribution and consumer access, FERA believes that the problem is not national copyright legislation. The problem has four main causes: The way films are financed in Europe today, online copyright infringement (piracy), varations in national contract law, and inadequate licensing practices. For European film directors it is sad and frustrating that the copyright debate has become so polarized that politicians seem forced to choose between creators and consumers. Because in the long term our interests are - and must be - the same: Legally offered quality creative content online at a reasonable price. As FERA member Cay Wesnigk so poignantly says: All we are asking for is Digital Fair Trade.

Elisabeth O. Sjaastad Film director & FERA Chief Executive

&!

También podría gustarte

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- 9 ST Lukes Medical Center v. TorresDocumento17 páginas9 ST Lukes Medical Center v. TorresKris OrenseAún no hay calificaciones

- AAO Paper 1 2022Documento5 páginasAAO Paper 1 2022Baskar ANgadeAún no hay calificaciones

- QNNPJG lSUK0kSccrTSStqeIPoUAJF27yLdQCcaJFO0Documento1 páginaQNNPJG lSUK0kSccrTSStqeIPoUAJF27yLdQCcaJFO0Viktoria PrikhodkoAún no hay calificaciones

- Keys of The Kingdom-EbookDocumento18 páginasKeys of The Kingdom-EbookBernard Kolala0% (1)

- Rights of An Arrested PersonDocumento4 páginasRights of An Arrested PersonSurya Pratap SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Retro 80s Kidcore Arcade Company Profile Infographics by SlidesgoDocumento35 páginasRetro 80s Kidcore Arcade Company Profile Infographics by SlidesgoANAIS GUADALUPE SOLIZ MUNGUIAAún no hay calificaciones

- PIL PresentationDocumento7 páginasPIL PresentationPrashant GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Legal Research BOOKDocumento48 páginasLegal Research BOOKJpag100% (1)

- HarmanDocumento10 páginasHarmanharman04Aún no hay calificaciones

- Lledo V Lledo PDFDocumento5 páginasLledo V Lledo PDFJanica DivinagraciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Intermediate To Advance Electronics Troubleshooting (March 2023) IkADocumento7 páginasIntermediate To Advance Electronics Troubleshooting (March 2023) IkAArenum MustafaAún no hay calificaciones

- Report On Employee Communications and ConsultationDocumento29 páginasReport On Employee Communications and Consultationakawasaki20Aún no hay calificaciones

- MedMen HochulDocumento67 páginasMedMen HochulChris Bragg100% (1)

- Certification: Barangay Development Council Functionality Assessment FYDocumento2 páginasCertification: Barangay Development Council Functionality Assessment FYbrgy.sabang lipa city100% (4)

- Boskalis Position Statement 01072022Documento232 páginasBoskalis Position Statement 01072022citybizlist11Aún no hay calificaciones

- 0452 s03 Ms 2Documento6 páginas0452 s03 Ms 2lie chingAún no hay calificaciones

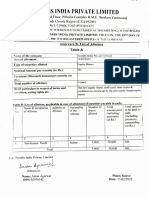

- Tectabs Private: IndiaDocumento1 páginaTectabs Private: IndiaTanya sheetalAún no hay calificaciones

- Cpi Sells Computer Peripherals at December 31 2011 Cpi S InventoryDocumento1 páginaCpi Sells Computer Peripherals at December 31 2011 Cpi S Inventorytrilocksp SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Posting and Preparation of Trial Balance 1Documento33 páginasPosting and Preparation of Trial Balance 1iTs jEnInOAún no hay calificaciones

- Bill of SaleDocumento3 páginasBill of SaleTobias PriceAún no hay calificaciones

- Administering Payroll For The United StatesDocumento332 páginasAdministering Payroll For The United StatesJacob WorkzAún no hay calificaciones

- PVL2602 Assignment 1Documento3 páginasPVL2602 Assignment 1milandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Springfield Development Corporation, Inc. vs. Presiding Judge, RTC, Misamis Oriental, Br. 40, Cagayan de Oro City, 514 SCRA 326, February 06, 2007Documento20 páginasSpringfield Development Corporation, Inc. vs. Presiding Judge, RTC, Misamis Oriental, Br. 40, Cagayan de Oro City, 514 SCRA 326, February 06, 2007TNVTRLAún no hay calificaciones

- GR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyDocumento2 páginasGR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyJoshua Erik Madria100% (1)

- 04 Dam Safety FofDocumento67 páginas04 Dam Safety FofBoldie LutwigAún no hay calificaciones

- 11 Physics Notes 09 Behaviour of Perfect Gas and Kinetic Theory of GasesDocumento14 páginas11 Physics Notes 09 Behaviour of Perfect Gas and Kinetic Theory of GasesAnu Radha100% (2)

- Sample Blogger Agreement-14Documento3 páginasSample Blogger Agreement-14api-18133493Aún no hay calificaciones

- Tax Invoice UP1222304 AA46663Documento1 páginaTax Invoice UP1222304 AA46663Siddhartha SrivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Editorial by Vishal Sir: Click Here For Today's Video Basic To High English Click HereDocumento22 páginasEditorial by Vishal Sir: Click Here For Today's Video Basic To High English Click Herekrishna nishadAún no hay calificaciones

- In The Industrial Court of Swaziland: Held at Mbabane CASE NO. 280/2001Documento10 páginasIn The Industrial Court of Swaziland: Held at Mbabane CASE NO. 280/2001Xolani MpilaAún no hay calificaciones