Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Center and Periphery Introduction

Cargado por

Humberto DelgadoDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Center and Periphery Introduction

Cargado por

Humberto DelgadoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

E d w a r d

Shils

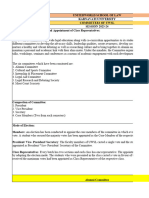

Selected Papers of Edward Shils, II C e n t e r a n d P e r i p h e r y E s s a y s i n

M a c r o s o c i o l o g y s *

T h e U n i v e r s i t y of C h i c a g o P r e s s Chicago and London

Contents

v/ Introduction vii I Society 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Center and Periphery 3 Society: The Idea and Its Sources 17 Society and Societies: The Macrosociological View 34 The Integration of Society 48 The Theory of Mass Society 91

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London 1975 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1975 Printed in the United States of America International Standard Book Number: 0-226-75317-4 Library, of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-87309

II Charisma, Ritual, and Consensus 6. Primordial, Personal, Sacred, and Civil Ties 111 *' 7. Charisma 127 8. The Meaning of the Coronation, by Edward Skils and Michael Young 135 9. Ritual and Crisis 153 10. Consensus 164 - 11. Tradition 182 v 12. The Sanctity of Life 219 III Status and Order

/HARVARD UNIVERSITY

LIBRARY MY 2 1975

13. 14. 15. 16. 17.

Power and Status, byHerbert Goldhamerand EdwardShils 239 Class 249 Charisma, Order, and Status 256 *K Deference 276 The Stratification System of Mass Society 304

IV Expansion and Dependence of the Center: Privacy and Primary Groups 18. Privacy and Power 317 19. Cohesion and Disintegration in the Wehrmacht in World War II, by Edward Shils and Morris Janowitz 345 20. Primary Groups in the American Army 384

k / o / c ^

vi

Contents Introduction

V Aspirations and Fragility of the Center: Traditional Societies and New States 21. The Concentration and Dispersion of Charisma: Their Bearing on Economic Policy in Underdeveloped Countries 405 22. Opposition in the New States of Asia and Africa 422 23. The Fortunes of Constitutional Government in the Political Development of the New States 456 24. The Military in the Political Development of the New States 483

i The members of the educated part of any society know how they are to be designated; they are designated by the name of their society. They are Americans, British, Frenchmen, Italians, Indians, Japanese, or whatever. They know that they share that nameor a minor variant of itwith their government and the territory on which they live and with all or most of the other human beings who live on that territory. Many educated persons do not approve of this type of designation. Yet, if they call themselves lawyers or machinists, fathers or sons, whites or blacks, Protestant Christians or Hindus, or several of these together, there still remains a sense of incompleteness. It is thought that they have to bear also the name of their "society." The "society" is that most inclusive yet bounded collectivity of which they are seen to be only parts. It is the whole formed of parts. But to say what that whole is is a hard task. The essays in this volume deal mainly with the properties of the larger, most inclusive structure of societies, with the varieties of this outermost structure, and with how it is maintained and changed. They deal with the influence of the outermost structure on the lives of the groups, strata, and individuals who live within it and of the limit of its influence over those component parts. This outermost structure is an intermittently appearing part of the lives of its members. It is also that which binds them in various ways and degrees into being a society. It is a necessary emergent of the existence of human beings. Every human being is born into and lives within an aggregation of other human beings who are bound within an outermost structure. The penetration of the outermost structure of society into the lives of those living inside it is limited by the influence of certain characteristics of human existence suxh^aTHn^erences in proximity, personal and erotic attachments, differences of cognitive interest and imaginative power, which are ineluctable constituents of the existence of society. There is, therefore, a continuous process of interdependence and antinomy between the outermost structure and those other constituents of society. The ebb and flow of this process is therefore a theme which dominates the essays in this collection. *& The fact that I refer to the ^putermosfNir the "inclusive" or the "larger" structure of society for lack of abetter term bears witness to the difficulties of delineation of my subject and to the extent to which it has been neglected in educated discourse and social science, particularly in sociology. Economists, working within the limits of their own concerns.

ff

viii

Introduction

Introduction

be

have analyzed economies or economic systems, by whichunless otherwise statedthey mean the economic system operating within theboundaries of a national state. At one time economists entitled their subject matter "national economy." More recently, "macroeconomics" has been a fairly well-defined branch of economic analysis. Students of politics, dealing with the sovereign state, the national state, or the central government, have HkewisenoTexperienced greater difficulties than have economists in defining the largest of the entities with which they deal. When they deal with "international relations," they postulate the existence of more or less autonomous political systems. Just as economists have taken "the economy" as their subject matter, so some academic students of politics have even revived the old term "polity" to show that they deal with a phenomenon of the same extension and inclusiveness as "the economy." It would appear from this that my subject matter in these essays is "society," and so it is. But saying that does not bring us very far. Economists have the market, all the arrangements and conditions which foster and distort it, as the major objects of their attention. Those who contemplate the polity have as their major object the central government and all that is done by it, and all those actions and arrangements which attempt to control it and to change it as well as the efforts which flow from it. But it is more difficult, at least in our present state of knowledge, to conceive of a society on the same scale and to define it clearly. Great writers like Tocqueville in De la Democratie en Amirique, and Macaulay in the first volume of the History of England, and Hal6vy in the first volume of L'Histoire du peuple anglais au dix-neuvikme Steele, have all dealt with whole societies, but they did not specifically confront the task which I have repeatedly attempted in the papers in this volume. The great sociologists have come near the subject but never confronted it directly. The tradition with which they have endowed us does not speak clearly on this point That is one of the reasons why the approach taken here is so tentative and provisional. It is an attempt to elucidate things which have seemed to me to be of very great importance but which are very obscure. It is terribly difficult to describe and analyze the processes and structures which form families and classes, neighborhoods and regions, schools and churches, factories and ethnic groups into a single society. Whatever the reason for this difficulty, whether it lies in the inherent difficulty of the task or whetherand this is closely related to that difficultythe tradition of thought about "society" as having a character parallel to but not identical with "polity" and "economy" has skirted this subject, it need not be determined here. The very name of "macrosociology," which has recently come into wider usage and which is perhaps derived from the parallel "macroeconomics," is evidence of an

awareness that there is a legitimate, indeed a very important object which has not yet come into full focus. When one seeks to discover this "larger society," various simple strategems present themselves. One of these is simply to refer to one feature of the economyto refer to it, for example, as "capitalistic society." This permits its location in time and space, but the intellectual value" of such a designation is negligible. Or, one can call a society by the name of its political system"democratic society" or "totalitarian society." These two, like "capitalistic society" or "communistfesociety," evoke certain significant features, but they are a shorthandjodescribe an object wjuch eludesJhe grasp of understanding. Another procedure"is to assert that the "larger society" is the society which resides in the territory governed bylhe_sovereign national state. This means designating it by the name of the state"or by tKename orthe nationality which presumably comprises the human beings living on that territory. This is certainly the most common practice. And it is not by any means wholly incorrectfar from itbut it is certainly not adequate. It raises a question about the"^> importance of nationality in the formation of society; it also raises a question about the significance of territorial boundaries and of a nominally sovereign authority over all that goes on within those boundaries. It certainly does not resolve the difficult problems which I have approached from various angles in the essays contained in this volume. -sita* To speak of a society implies that there are certain properties which" constitute the various groups, strata, and individual members of that society as a single inclusive entity which is not simply an additive list of all the different groups, strata, and individuals. These groups, strata and individuals are linked with each other into a society. Democracy and totalitarianism refer to certain features of that linkage, but they are too narrowly limited in their reference. The linkage is more ramified and pervasive than that produced by the actions of a monopolistic party in a totalitarian society or by those of an elected government in a competitive party system. I do not wish to commit myself to the proposition that*" societies can or cannot be characterized by a single term. If they can, it will have to be one of a very differentiated family of terms and not one of the alternatives of a simple dichotomy, which is so common a method of characterization in social science and in lay thought. I have tentatively chosen the term "integration" to bear the burden of our vague thoughts about the constitution of the parts of society into a whole society. In recent years, the term became widely used to refer to the relationship of ethnic minorities to the society in which they live. The integration of the black sector of American society is only orit particular variant of the more general class of relationships between j center and periphery. In their various forms and intensities, the phenom- / ena of integration operate in every sphere of the life of society. The term /

Introduction

Introduction

xi

is often used to refer to local communities, for example, a "wellintegrated community," or a "highly integrated family," or the integration of states in a region or continent It has been used to refer to relationships of smaller radius; in all these usages, there are certain features which are common. But when I speak of the integration of society, I refer not only to the conformity of expectations and performances and the acceptance of distributions of rewards, to boundaries, and to collective self-designations but also to the center in its relations with its various peripheries. Thus whether the term "integration" is used or not in the essays which follow, I refer to the linkages of the parts of societychurches, military units, friendships, business firms, trade unions, neighborhoods, familiesto the institutions, roles, or symbols which are thought by their members to be characteristically constitutive of, and therefore central to, the "inclusive" or "larger" or "whole" society. Integration, in its most abstract sense, is the articulation of expectation and performance. It can occur in a relationship between two persons, it can occur in the structure of a whole society. It can be produced by coercion, payment, or consensus about moral standards. It is not always direct in the sense of linking a person, a group, or a stratum directly to something emblematic or representative of the larger society. Integration is a very heterogeneous affair. It is very unevenly distributed in any given society, and it is also an intermittent thing; it fluctuates within and among the parts of society. A given society might be highly integrated in some sectors, poorly integrated in others. Given sectors of society might vary through time in their degree of integration into the larger society. The threat of coercion might be very significant at one point in time, at another it might fade and yield to payment or consensus. I do not deal much in this volume with payment, that is, the market, as a means of integration; nor do I, except in passing, discuss the very important phenomenon of coercion, which plays a significant part in forming the action or individuals and groups into a condition of integration and in maintaining that condition. In attempting to arrive at a more just assessment of the actual state of affairs prevailing in modern societies and to elaborate the categories appropriate to this just assessment, I am incessantly and acutely aware that exchange and coercion are parts of the "macrosocial" phenomenon. Nonetheless, these essays deal mainly with the variations and mechanisms of~cdnsensys. There are various reasons for this choice. For one thing, e^xchangt^has been very elaborately analyzed by economists, and its place~m the integration of society requires, so it seemed to me and so it still seems, that the consensual setting of the market be analyzed more adequately than it has been hitherto. Coercjaajs a marginal phenomenon which cannot possibly integrate nfiich of a society over an extended period of time. Its effective exercise over certain persons depends on a setting of

the consensus of many other persons; this setting might be real or presumptive. The threat of the exercise crf)erCtj)nwhich is more often in operation than actual coerciondependsfor its effectiveness on a belief on the part of the threatened and the threatener that there is some consensus regarding the legitimacy of the threat of coercion among/ "third parties." The relations between consensus and coercion are numerous and subtle and it is urgent to analyze thm. I do not, however, do that in the essays which follow. I have directed my attention primarily to consensus, because it is so evidently a major element in the integration of society, and it has despite numerous treatments in passingsnot often been made the object of persistent investigation. Furthermore, a very important strand of modern social thought has emphasized, as the chief characteristic of modem society, the dissolution of consensus and consequently the disintegration of society. Very much of the intellectual tradition in which I grew up put the dissolution of consensus into a very prominent position. As I began to find my own way, the inadequacy, descriptively and theoretically, of this view of modern society became apparent to me. On the other side, many of those writers who discussed consensus in a way which did not entail disintegration, spoke of it in such a schematic and even simplifying way that it was clear that nothing like the consensus they described existed in modern societies. What they described was too explicit, too stable, too comprehensive. That is why a considerable amount of what follows in this volume is given over to stressing the shifting, vague, intermittent, and indirect character of consensus; assess- ^/ ing its powers and limitations, its fragmentariness and fragility, its persistence and its intermittence; and then attempting to discern its existence and working in modern societies. . It has never been any different and it is not likely to be different in the future. Such consensus as exists in any society is, moreover, never shared by all its members; nor is each of the numerous consensual solidarities among the various strata and groups within society congruent with certain others to such an extent that they are in effect self-contained. There is an infinitude of criss-crossing and overlapping. But alongside this tenacious and penetrating intertwinement and ramification there are also pockets of the far-reaching isolation of certain groups from most of the rest of society. Even those which are not isolated in this way are partially isolated from each other. They would not be groups with a distinguishable character; they would be boundaryless and therefore not recognizable by their members or by observers as groups with distinctive properties. This is one aspect of the limitation on consensual integration to which some of the papers in this volume are devoted. I have wished to show that Leviathan can never have things entirely his own way for any considerable length of time. There are always some parts of society which he cannot swallow up and assimilate.

1 1 \ i I i

xii

Introduction

Introduction xiii regard themselves as the exponents of the "conflict model," which they contrast with a "consensus model." Their polemical, even political interest has thus far prevented them from pursuing their analysis seriously. Even if wrongheaded, a serious, unremitting analysis of coercion and conflict would throw up questions which would much more subtly illuminate the subject which concerns us here, namely, the powers and influences of the inclusive society which subsists alongside numerous parochial loyalties and which survives conflicts. But there has been no help forthcoming from the friends of the "conflict model." The problem remains: How are individuals, groups, and strata linked -v together to constitute a society, and not just all those alive at a single / moment but through time as well? The shape of all these society-forming f linkages has an existence of which time is one dimension. Time provides * not only a setting which permits the state of one moment to be compared heuristically with that of another moment. Time is also a constitutive property of society. Society is only conceivable as a system of varying states occurring at moments in time. Society displays its characteristic features hot at a single moment in time but in various phases assuming various but related shapes at different and consecutive moments of time. It seems to me to be impossible to deal with the integration of society without regard to the vicissitudes of the "natural history" of society. These are the intellectual interests toward which the papers gathered together in this volume have been moving over about four decades. The movement has not been in a straight line. There has been much circling about the same point; much redoubling of steps, much going back to the beginning and starting again. New ideas have occasionally been added; more often it has been the older ideas which have been put into a slightly different intellectual context Some facets previously neglected have been brought forward. The aim has always been to make a little more explicit what was more dimly apprehended previously. Time and again I have asked myself whether this search for the structure of societyof whole societiesis not a vain undertaking, perhaps even an idle one. Sometimes I ask myself whether the individualistic utilitarian interpretation of society is not adequate, or why the Hobbesian-Marxian view is not adequate, when they not infrequently seem to account for the coordination of the actions of many groups, strata, and individuals into society. I ask myself these questions quite often, but I invariably come up with the same answer, namely, that such views are not enough and that they are not enough in an important way. In some respects all these papers say the same things, and they say them in a way which to me is exasperatingly vague. Yet I think that it is not unduly immodest to say that here and there the line has been pushed forward a little. I shall now say something about how these ideas developed, about their sources in books, teachers, and colleagues and in immediate observations drawn from investigation and the experience of

Societies are full of conflicts; conflicts are endemic in human existence. Scarcity is an unceasing fact of life, despite what the preachers of plenitude say. Quite apart from the ecological situation of human life, human appetites and desires are expansive. Their subsidence is a phenomenon to be explained, but subsided or expanding, they are always confronting the fact of the scarcity of the objects they seek for their satisfaction. Conflicts are patently antithetical to consensus and, hence, to integration. Still, conflicts within societies do not prevent the societies from continuing to exist. The parties to these conflicts, despite the temptations which conflict offers to hyperbolic rhetoric, seldom deny their membership in those societies. Those wh^r^jn^csuflici^ith-each other respond_toJhe namej>y which, they designate their^memb^rshipjn their somehow encompassing-society, and they recognize some identity throughthiie-and across the lines of conflict. They regard themselves as indisalubly-bound to their societies; and so, indeed^they are. Society, even an apparenthforderly and internally relatively peaceful society, is a great motley of activites, a tangled skein of an infinity of ties which, in ways difficult to formulate, constitute a whole. It has boundaries of which those within it and outside it are generally aware. It is an inchoate sprawling mass constantly spilling over its boundaries and receiving ideas, works, and persons from outside them, but whatever comes within its boundaries becomes different in consequence of being there. Assimilation testifies to an assimilating society, resistance to assimilation testifies to the presence of society which grips whatever comes within its boundaries. The grip is not necessarily one which assimilates into a consensus; it is possible to be bound into society by bonds which are not predominantly consensual. * One thing is clear: there are not and can never be any human societies which are wholly consensual; nor have there ever been societies so wholly disintegrated that there were no links at all binding many of their ^individual members together. For a long time there has been a tendency among intellectuals in Western countries to deny this obvious fact For some reasons, good and bad, they have accepted uncritically a tradition which has depicted modern society as if it were on the verge of the state of nature according to Hobbes. This situation was not improved by the introduction of a vulgar Marxism which unthinkingly made membership in society identical with subjugation by coercion. As a result of a very selective imagination and an almost deliberate blindness, the view has become rather pervasive. It has come to appear self-evident It has taken hold even among sociologists, who should, of all persons, know better. The great tradition of modern sociology has always included this view as one of its strands, and the increasingly "empirical" character of sociology has not been able to expunge it. Recently this extremely naive view has been given a new impetus in sociological thought by a number of writers who

xiv

Introduction

Introduction

xv

life. Retracing these steps might help to make more tangible the incessant objects of my intellectual striving of more than four decades. II When I first began to think about problems which later were classified as sociological, I did not know about the position which I now tentatively hold. It was on the basis of study of nineteenth-century literature, especially French literature but also Russian, German, and American, that I began to reflect on the intellectuals' withholding of their approbation from their own societies and their complaints and counsels about their isolation. As I recall, I did not really believe in their assertions of isolation from society; I saw them as connected with it in all sorts of ways. I also at this time began to read the literature of Marxism and was made aware of the enormous aspirations of Marxism to transform the large societies of Europe and America into communities which combined total individual freedom with a total absence of conflict. Rousseau's Contrat social and especially the notion of a volonte generate aroused my appreciation and abhorrence. The idea of the absorption of the individual will into a higher will which transcends that of the individual intrigued me, as it still does, and much of what I have thought since that time has been impelled by a desire for a better understanding of that idea. The complete absorption of the individual which Rousseau appeared to me to desire was both repugnant to me morally and unrealizable as well. Georges Sorel was another of those writers who made an unpleasant but nonetheless deep impression on me. I thought that his justification of the execution of Socrates was wrong, but at the same time I also had some sympathy with the notion that a society has a set of moral and cognitive beliefs, adherence to which is a condition of its survival. In his contempt for what he conceived to be the moral abdication of the bourgeoisie of his time I saw a conviction that the participation of the elite of a society in a consensus of beliefs with the rest of the society is a condition of the continuation of that society in its existing form. The first volume of Taine's Origines made the same impression on me. Yet, at the same time, I was not ready to be convinced that societies were such flimsy and easily disruptable affairs. There was apparently already some reality in the volonte generate in the society I knew. I thought that it possessed an envelopingness and a tenacity which rendered it obdurate to the jolts of ordinary life and intellectuals' criticism. At around this time, I read Sumner's Folkways, which dealt with this obduracy to intentions of change, but I thought the idea of the "mores" much too amorphous as an account of the tenacious structure of society. Even earlier, when I was quite young, I was struck by the tenacity of the attachment of individual human beings to their societies and by the

way .in which they reached out to hold on to those societies. I had observed immigrants to the United States from Eastern European countries, where they had not fared at all well, refer to "the old country" as "home." I was struck by the strength of their unreflecting belief in their membership in societies in which they were no longer actively participant; I was struck too by the way this belief descended without reflection to their offspringswhich was one of the grounds of the rash of "fellow-traveling" among young intellectuals of Eastern European Jewish origin in the 1930s in the United States. I was no less equally impressed with the way in which they had become enmeshed in their new society. (This was one of the reasons why, when I later read the writings of W. I. Thomas and especially Robert Park, their observations on the assimilation of immigrants called forth such a sympathetic response.) I had also been impressed by the obstinacy with which some of the forces of union in the American Civil War refused to allow the Southern states to secede. When I first began to entertain the problem of "what makes a society stick together and what causes it to come apart"which a delightful old London bookseller once defined as the subject matter of sociologythe society which had once been ruled by. the Romanovs had been brought together again as the extensive disintegration of the civil war receded. Thefirsttrials of the late 1920s had already occurred, and it was clear already that Soviet society was not being held together by the natural harmony of freie Menschen auf freiem Boden as Max Adler formulated the socialist ideal. These crude and patchy thoughts about how societies became reconstituted as societies after civil war or revolution also gave me occasion to think about what it was which was being reconstituted. Except for the separation of Norway from Sweden, there had been no breakup of a stateapart from the dissolution of the multinational, multiethnic Hapsburg and Ottoman empires, which I did not look upon as single societies. I could see the conflicts and miseries of societiesthe United States was showing fissures in the early years of the Depression of 1929, and the Weimar Republic, of which I knew only very little, was apparently the scene of frequent and intense conflicts. Yet the opposite was no less present in my mind. I also noticed fairly early that societies which had expanded continuously on a surface unbroken by water or other societies were regarded as morally unexceptionable by persons who criticized the expansion of societies overseas ordiscontinuously over land. I did not make much of this at the time although in later years I saw that it said something about the significance imparted to territory and boundaries. At every stage of my life over the past forty years, the grip of society on its members and the attachment of individuals to societyand by this I do not mean the grip of the immediately present group on its members or the attachment of the members to that group or the government's grip exercised through its capacity for coercionhas been borne in upon me.

xvi

Introduction

Introduction xvii forms of social action. His analyses of large societies were done before he began to build complex structures out of the most elementary constituents of action. It might well be that the task is not hopeless, but even if it could be done, it could be done only after the distinctive features of the larger society have been discerned on their own. They cannot be constructed deductively as I thought they could be. Although the intellectual air of the 1930s was filled with talk about "capitalism," "totalitarianism," "the free society," and the like, there was scarcely any explicit discussion on a more general plane of the bonds which constitute society. Max Weber's writings were beginning to be known in English-speaking countries, but bureaucracy as a mode of organization of authority characteristic of large-scale societies was what attracted attention. The more fundamental and potentially more fruitful analysis of legitimacy was not pursued. The increased popularity of Marxism contributed nothing to the problem, since its interpreters and proponents were, oh the whole, so unserious intellectually and so eager to find easy recipes. When Karl Mannheim's Mensch und Gesellschaft im Zeitalter des Umbaus appeared in 1935, it thrilled me by its large perspectives. Mannheim proposed the total planning of societywith which I was not at all sympatheticbut he did not really say what the whole society which was to be "totally" planned had been before it fell into the crisis which he purported to describe. His view of the "laissezfaire society" which was to be replaced by the totally planned society was not much different from the traditional conception of the market He found it easier to describe the nonexistent, fictitious society which was to be createdas a societythrough planning than to analyze the working of the existing society. Like other famous figures in the history of modern sociology, he had an eye which was quicker to detect and penetrate into "breakdowns" than into the "ongoingness." Forty years have passed since Mannheim wrote Mensch und Gesellschaft. There are still no societies in the West which are "totally planned," but somehow these societies have persisted, although with many changes. Mannheim did not help to discern the process through which these societies were able to persist as societies without recourse to such a drastic, disjunctive change of structure as he proposed. He made another attempt in a long paper which he presented to "The Moot"1; there he explored the significance of paradigmatic images. This was the closest he came to dealing with the consensus of beliefs connected with the center, but he did not continue this line of inquiry. (Unfortunately, although I saw him frequently during and after the Second World War, I did not have the problem sufficiently in focus in my mind to be able to

And just as impressive to me has been the amorphous inarticulateness of this grip and clingingness. To practically all of those who have participated in these attachments, they have seemed ineffable.1 What is more, they have existed alongside dissatisfaction and resentment against the objects to which they have been attached, and together with active antagonism against other groups and individuals within that same society to which they were so attached. When I came to the University of Chicago, I began to read the writings of Simmel. He had asked the question: "How is society possible?" ("Wie ist Gesellschaft moglich?")3 He answered it in a way which even at that time was not really satisfying; he said that it exists through the interaction of individuals, and, in saying so, he avoided the problem of the "unseen hand" working through a multiplicity of interactions. Simmel postulated the formation of the larger society from the multiplication of interactions in face-to-face relationships. It is true that he often dealt with things other than these, but in principle this was what he was committed to. I was attracted by the possibility of constructing a description of society by the differentiation and multiplication of interactions between two persons and by extending these interactions to ever larger numbers of participants in networks of interaction, so that a picture of an entire society would be constructed from direct, face-to-face links. Society was, nonetheless, not formed simply by interaction, however important that was. The interacting groups or strata might be the means of communication or connections with parts of the society which were not interacting with each other. The connections of these latter groups or strata or individuals which were mediated through face-to-face interaction were as important as those which were constituted by the face-to-face interaction. Simmel was in fact not asking the question to which I have been seeking an answer. He was trying to elucidate the most elementary properties of interaction. Max Wober was doing a similar thing in the first chapters of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Beginning with the elements of the action of a single actor, he advanced into a social action which he then elaborated into four types of social action, and from there onwardby the addition of further elements, which emerged mainly from the most elementary definition of actionhe moved into the grandiose analyses of the charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal forms of authority. For a time, I imagined that this was how the idea of a whole society might be constructed. I was probably wrong. Max Weber did not arrive where he did by multiplying and differentiating the most elementary 1. Simmel, in an offhand way said: "Awareness in principle that he is forming a society is not present in the individual" Simmel, Georg, Soziologie (Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot, 1908), p. 31. 2. Ibid., pp. 27-45.

3. See Diagnosis of our Time (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner Co 1943.) ' V

xviil Introduction draw him into discussion about it I regret this very much now because I think this would have benefitted his own work and mine. But I was too ignorant to know just how to take hold of the problem.)

Introduction

xix

Ill Things were intellectually at loose ends during the 1930s. Harold Lasswell was a young teacher at the University of Chicago. He was the most sophisticated of all the teachers there in his knowledge of the main European literature which interested me, and he was very daring too. He spoke often about what he called "configurative analysis," which must have been something like what I would now call macrosociology. Unfortunately at that time, his conception of power seemed to concentrate on manipulation and coercion. Nonetheless, he had a remarkable sensitivity and a widely ranging curiosity which disclosed the relevance of beliefs which were not exclusively political in their content for the distribution of power in society. In those years, the University of Chicago Press had published a series of works on "civic training." These were the fruits of Charles Merriam's interest in the beliefs which sustain and change regimes. Harold Lasswell was his most original student; his originality consisted in bringing the insights of the newer generation of European writers and psychoanalysis to the study of the matrix of political activity. Lasswell did not deal with legitimacy in his treatment of political power; he did, however, speak about myths. I thought this was disparaging toward the deeper implications of the conception of legitimacy. Lasswell also knew a lot about the history of nationalism in modern times, and he had an extraordinarily lively mind and very much else. I gleaned from him a few grains of ideas which grew a little in different settings. I owe to him my interest in "deference," which I soon began to connect with the "moral order." Outside the university and the books I was reading, events in the world were forcing my attention into the same direction in which my thought was already tending. In the 1930s, the United States and the liberal capitalistic democracies of Western Europe were under the strain of large-scale unemployment, and there was much pessimism about the recuperative prospects of these societies. It was common among publicists and some academic social scientists from about 1932 onward to contrast the dilapidated, ramshackle condition of the North American and Western European societies with the solidarity and eagerness for concerted, authoritatively directed action which they said was the prevailing feature of society in the Soviet Union, National Socialist Germany, and Fascist Italy. The solidaritythe term "integration" was as popular then as "charismatic" is nowof the latter societies was attributed to the fact that their members "had something to believe in." It was said that they had "a faith"; the term "ideology" began to be )

widely used in the English-speaking countries for the first time. Although it was acquired from the Marxist writings, which were then being more widely read than heretofore, "ideology" was given a wider meaning, broader and less derogatory, than it was in its specifically Marxist sense. It was used to refer to an all-embracing belief which answered all questions and which offered the individual a belief that he had a "place" in that larger order of things which was explained by the ideology. Much importance was attributed to the function of these totalitarian "faiths" or "ideologies," which, in giving each individual a "place" in the movement of history, also gave him a sense of his own dignity in consequence of that legitimated "place." I was not sympathetic with this view; I suspected and in some cases knew that it hid an unworthy admiration of wicked societies. Yet I did not counterpose an alternative to it I agreed that beliefs were of consequence. At the beginning of the thirties while I was still an undergraduate I read through all of Durkheim's works. The one thing in all his writings which appealed to me was his discussion of "anomie." My first readings in Max Weber made more receptive my sensitivity to the varieties of beliefs about "serious" things. I had too much experience in the observation of religious and political sects and I had studied too much theology and the history of the Christian churches and sects to regard belief simply as "error," "rationalization," "reflection," or as an uncomfortable irrelevanceas so many social scientists of my generation did. I had the good fortune when I came to the University of Chicago to become more familiar with Frank Knight's ruminations about the tenacity of beliefs. Knight was a rationalist who detested many of these beliefs, but he was insistent that they be recognized. Unlike Pareto, whose Traiti I studied about this time, he did not regard the rationally or scientifically unjustifiable beliefs with levity. I also attended Robert Park's last course at the University of Chicago, It was on "Collective Behavior" and dealt with revivalist movements, panics, riots, and other phenomenon of "mass emotion." From Park's lectures and from the conversations which we had when I sometimes accompanied him on his way home from the university after class, I got a clearer, understanding that very little could be accounted for in society unless beliefs were considered. Park often referred to the "moral order" and to "norms." W. I. Thomas's conception of the "definition of the situation," undifferentiated and unclear though it is, also suggested that belief was important Academic social scientists and intellectual publicists would readily have granted this for all societiesoriental, African, ancient and medieval Europeanbut they were reluctant to acknowledge it when they dealt with modern Western societies. As a result of all this, although I was repelled by the admiring overtones of those writers who emphasized the beneficent beliefs of Nazis

w xx Introduction Introduction xxi

and communists, I had some common ground with them. I shared certain of their postulates. At that time, I still accepted much of the conception of modern liberal society which was to be found in Tbnnies, and in Simmel's "Die Grossstadt und das Geistesleben" which I admired so much that I translated it into English.41 accepted that beliefs v/ereT .constitutive-part.o_society and that modern Western societies had undergone a dangerous attrition of belief. From Tonnies and Simmel I assimilated the view that the development i of the large-scale, urban, capitalistic, individualistic society was one in which the larger society with its moral order had dissolved into a multiplicity of individuals and small groups, each with its own purposes and interests. These, at most, allowed compromise but not the sense of_ identity and attachment to symbols of the whole which, it was implied, had characterized the society of the preceding stage of Western history. R. H. Tawney, although he was writing the history of thought and opinion, was actually expressing a view of what modern society was when he wrote: "Religion has been converted from the keystone which holds together the social edifice into one department within it, and the idea of the rule of right is replaced by economic expediency as the arbiter of policy and the criterion of conduct." "Society . . . is a joint-stock company rather than an organism and the liabilities of the shareholder are strictly limited."5 I held this view ambivalently. It contradicted my conception of conduct as "normatively oriented." The "theory of mass society" was beginning to take form. The publicistic admiration for the all-embracing consensus of German society under the National Socialists and of Soviet society was receiving a more intellectual formulation in the writings of Paul Tillich, Emil Lederer, Karl Mannheim, and Erich Fromm. The Frankfurt Institut fiir Sozialforschung was the source of many of these notions. A consensus was forming. Marxists, refined and vulgar, liberals of faint heart, and other haters, high-and low-brow, of modern society, supported each other. The great tradition of sociology which saw the world in the dichotomy of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft was beginning to join forces with these other blocs of opinion. The condition alleged to exist in the Western countries was declared to be a prelude to totalitarianism. The incipient "theory of mass society" was both an ostensible description of liberal, democratic societies in the twentieth century and an analysis of their transformation into totalitar4. At the end of the decade 1 used it for my undergraduate students. More than thirty years later, after I forgot that I had translated it, Professor1 Donald Levine reprinted it in Georg Simmel: On Individuality and Social Forms, edited by Donald Levine (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1971) pp. 324-39. 5. R. H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (London: John Murray, 1933), pp. 279, 189.

ianism. The reduction of men to "isolated atoms" in mass society was said to be an affront to their needs for solidarity and for belief; such a situation would be unbearable. "Political religions" were the result of the beliefless, excessively individuated condition of man in the liberal democratic society. The hunger for solidarity drove human beings to seek out or form and adhere to groups and societies to which such an attachment was possible. Whatever man's fundamental needs for normatively legitimate order, modern liberal-democratic, capitalistic societies failed to meet them. In contrast with this situation, the totalitarian societies, by presenting a comprehensive scheme of ultimate values intelligible and persuasive to everyone, were meeting fundamental human needs. This made no sense to me. It did not correspond with what was observable. I could see, in the United States in the 1930s, how, despite the demoralizing influence of the Depression, great numbers of persons remained attached to their society. One could scarcely avoid being impressed with the part played by President Franklin Roosevelt in strengthening attachment to American society. The president was bitterly criticized in some circles, but even in those circles there were many whose attachment to the country could not be doubted; they were not merely seeking to protect their own property and status. In intellectual circles too there was a renewal of civility after its absence for many decades; this too gave evidence of attachment to the society without the adduction of an explicit, comprehensive, and coherent doctrine or ideology. The consensual element in American society was very far from extinction. This was quite obvious although it was much more difficult to delineate its form and force. In National Socialist Germany and the Soviet Union, the two societies which were being held before us as being wholly consensual, very great numbers of persons were being imprisoned, interned, done to death, exiled, or menaced. One could not, unless one was already a determined partisan or a complaisant victim of propaganda, fail to notice this. The appearance of consensus was maintained by the coercive segregation of dissenters and by murdering or intimidating them. I did not doubt that: there was a good deal of consensus around the centers of these two societies, but it was certainly far from complete. In addition to the frivolous, who were driven along by the currents of opinion, and those who were simply malicious, there were also the decent persons who had experienced National Socialism at close hand or who had observed it with penetrating understanding and who were alarmed by the danger of its spread to Western Europe and America. Some of them thought that the German situation was prototypical for all of the liberal-democratic societies of the West. There were also less engaged scholars who asserted that liberal political democracy and the rule of law rested on consensus. Carl Joachim Friedrich was one of the best and

xxii Introduction most learned of these, but their thought was too schematic for me. They did not venture onto the structure of the required consensus; they did not attempt to delineate its actual condition. I was on their side, but I did not make any progress through this alliance. Their definitions of consensus gave a monolithic impression of a body of beliefs consensually held, equally and simultaneously, throughout the society. Their belief that some agreement was a precondition of the peaceful resolution of disagreement was correct, but it seemed too general. They never gave any illustrations, or at least none that I understood at the time to be pertinent They did not go into the pattern of coexistence of conflict and consensus, although their conception of consensus as a limitation on the intensity of conflict placed this task on their agenda. The coming of the Second World War did not improve my thought on these matters. My ideas were vague, loose, and contradictory; their vagueness and looseness obscured their contradictoriness. On the one side, 1 accepted, more or less, the modern sociological version of the Hobbesian description of the state of nature in its application to Western societies. Yet I was also convinced, in principle, that some minimal measure of consensus was required for the existence of any society. In the few papers which I wrote on social stratification before the war, I nroceeded on the belief that there existed a vague, unarticulated /acceptance of certain criteria regarding the relationship between merit \ and reward and that the criteria by which deference was accorded received a fairly consensual affirmation. Yet I also knew of the antagonism between members of different strata and the conflicts, sometimes violent, conducted by some members of one stratum against members of other strata. At the same time that I was convinced that a minimal degree of consensus was necessary to the existence of a society, I was even stronger in my conviction that no large, differentiated society could ever attain or persist in the kind of consensus sought by totalitarians and idealists. Two questions resulted from this. One referred to the patterns in the mind and in the culture of these conflicting elements; the other referred to the character of the consensus which could exist under those conditions. IV The period between the outbreak of the war in Europe and the entry of the United States into the war was one in which myxapproach began to change. Early in this period, I wrote a long paper on "The Bases of Stratification in the Negro Community" for Professor Gunnar Myrdal's study of the Negro in America. Such data as I could obtain from direct observation and from documentary sources showed consensus riddled by

Introduction xxiii contradiction and ambivalence regarding the criteria on the basis of which esteem was accorded. These data were very useful to me. Alongside my interest in the "whole society" and its presumed consensus, I was reading the literature on religious dissent and toleration jn seventeenth-century England; I was also interested in the literature on friendship. In 1941 I also undertook an investigation on the North Side of Chicago of small associations intended to propagate or sustain National Socialist and American "nativisf' views.. The seventeenthcentury debate on religious toleration, particularly John Locke's Letters Concerning Toleration, and the observation of isolated "pockets" in society posed a problem for my understanding of societywide consensus. The religious and political sects which I had been interested in were antagonistic to the rest of their society while claiming that the other members of that society should act toward them as if they were fully qualified members of that same society. I was not interested in scoring points against their logical inconsistency but rather in fathoming this simultaneous rejection and affirmation of membership in society. Then there was another side to the pluralism which I was discovering. It was more positive, but it raised the same sort of question regarding the amalgamation of diverse and separate groups and strata into a single society. I had studied Charles Horton Cooley on "primary groups," Elton Mayo's The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization, and T. North Whitehead's Leadership in a Free Society. Simmel's insights into intimate attachments, and Durkheim's effort to establish a new civic moralityvaguely resembling, at least in intention, what I later called "civility"to be mediated through independent "professional groups," and the "pluralism" of Leon Duguit and Mary Parker Follett came to life in my mind when during the years from 1942 to 1945 I pondered the power of the German armed forces to resist disintegration under a fairly steady sequence of reverses in battle. Freud's Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse was helpful to me in my search for the lines of filiation which bound the individual to the larger society or to the center as I later called it. My collaborator in these years, Dr. (then Lieutenant-Colonel) Henry Dicks, was a psychiatrist sympathetic with psychoanalysis and a man of warm and understanding heart, even of enemy prisoners of war. He emphasized the need to demonstrate manliness as the source of the German soldier's conduct under arms. This was an attractive explanation, but it neglected the role of the soldier's immediate companions in training and combat and their role in sustaining his adherence to the ideal of manliness. It overlooked the content of manliness which included fidelity to comrades. It neglected the force of attachment to the larger collectivitiesthe Wehrmacht, the Nazi party, the German state, and German society. The

xxiv Introduction psychoanalytic interpretation treated the elaborate structure of society simply as the setting of sexual competitiveness. It raised no questions about the way in which that structure worked except to imply that it was sustained by sexual competitiveness. This solution begged the question. I thought that I found the answer in the primary group as the mediator of beliefs and rules from the authority of the larger society. I recalled Hermann Schmalenbach's description of the Bund in his essay "Die soziologische Kategorie des Bundes."6 It was a Gemeinschafi without the ties of kinship and place. This was helpful because it made me more aware than I had been before of the role of certain types of primary groups in affirming and supporting ideals for entities far wider than the primary group. It made me reinterpret the meaning of Cooley's hope that the ideals of the primary group would become the ideals of American society in its largest and least intimate structure. Cooley had hoped that the primary groups would become the centers of American society. I now began to see the primary groups as the mediators of the beliefs and symbols of the center. I also read Ernst von Salomon's Die Ge'dchteten with its account of the fanatical nationalist youths who assassinated Walter Rathenau and who found in the Freikorps a way to sustain their ideal of the German nation and means to realize a "genuinely German state." Later on, I saw this phenomenon in a different light, but at this stage it was taken as another instance of the primary group as the mediator of the symbols of the larger society and as the sustainer of its value. When his military service was over, Morris Janowitz, who had been my close collaborator during the war, came to the University of Chicago to complete his studies. There in the spring of 1946 we wrote the "Cohesion and Disintegration of the Wehrmacht in World War II," in which the idea of interplay of attachments to the larger society and to the intensely experienced, small primary group was developed. The long and short of this was that the stout-hearted conduct in combat of most of the German soldiers with whom we dealt was only slightly, and then indirectly, influenced by the ideological espousal of the beliefs of National Socialism. Vague attachments to German society and the ideal of National Socialism mediated by personally acceptable zealots each played a part Above all, however, concern to maintain the integrity of, and to remain firmly emplaced in, the primary groups provided the main ground for the continued obedience of German soldiers to the commands of their officers and for their exercise of initiative and resourcefulness on 6. Walter Strich, editor, Die Diaskuren: Jahrbuch fur Geisteswissensckaften, vol. 1, (Munich: Meyer und Jessen, 1922). pp. 35-105. I first encountered Schmalenbach when I translated the manuscript of Ernest Frankel's Der Doppelstaat into English in order to help him to find his way in the United States. Frankel later became professor at the Free University of Berlin and struggled to save it from its assailants. My bread was not vainly cast upon the waters.

Introduction xxv behalf of the general goals set by their military superiors, near and remote. This helped to settle for me the problem raised by the laudators of the totalitarian societies when they wrote of the "faith to live for" or of.the "ideology" which allegedly pervaded those societies. It showed me that many of the soldiers were rather deaf to the ideological "beliefs" for an active acceptance of which they had erroneously been praised; it showed me that some of the response which such beliefs aroused was the result of the presence in the soldiers' immediate environment of a person who espoused those beliefs and to whom the soldier was attached on personal grounds. This was a very simple observation once it had been made, but it was a step forward for me in my search for the integrating mechanisms of large societies and for the limits of "systems of belief in the working of those mechanisms.7

Through the second half of the 1940s, I continued to work on primary groups in armies. I reinterpreted the tradition which I had inherited, fusing the tradition of reflection and investigation concerning primary groups with a long enduring concern with the function of primary groups in the maintenance and change of large collectivities and society.8 I delivered a series of Jectures on "The Primary Groups in the Social Structure" at the London School of Economics in the autumn of 1947. (I did this a number of times at the University of Chicago too, beginning in 1956.) I also began to lecture and conduct seminars on "The Structure of Large-Scale Societies," at the London School of Economics in the 1940s and at the University of Chicago in the 1950s. It was my intention when I began this program of teaching to write two books, one entitled "Consensus and Liberty: The-Social and Psychological Foundations of Political Democracy"; the other on "Primary Groups in the Social Structure." The former was written out in a complete draft; the latter was sketched out more roughly but at some considerable length. I put both of them aside when I went to Harvard University to work with Professor Talcott Parsons on what later became "Values, Motives and Systems of Action," and the general statement in Towards a General Theory of Action. A number of things of some importance for subsequent phases of my work came out of this collaboration. One of them was the inter7. I was heartened in this view by the invocation by Professor Paul Lazarsfeid in a lecture which he delivered in Oslo in 1948 very shortly after our paper appeared and then a few years later by his adoption of this hypothesis in his and Professor Elihu Katz's Personal Influence (Glencoe, III.: The Free Press, 1955). 8. See my "The Study of the Primary Groups," in H. D. Lasswell and Daniel Lerner, editors, The Policy Sciences (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1951).

xxvi Introduction dependence between systems and subsystems; this was one of the things which I had got from reading Pareto's Traite, but the environment was not congenial to this kind of thought in the 1930s and I did not have the equipment to do more than respond favorably. My friendship with Professor Parsons provided this compelling intellectual environment. Another benefit of this collaboration was the clarification of the distinction between culture and social structure; still another was the threefold classification of cognitive, moral, and expressive actions. All these accomplishments were on an extremely abstract level, and they represented only more systematic and more explicit statements of ideas which I had already possessed but had not thought through to anywhere near the same extent we were able to do together. Another product of this period was the classification of the properties of objects of orientation.* These distinctions and classifications, although rather scholastic in appearance, were helpful to me in developing my ideas about the limited capacity of many human beings to sustain a direct, continuous, and intense relationship to the center of their society. In a certain measure too they formulated in a very abstract way some of the things I had been thinking about over the past decade. The interdependence between system and subsystem was a restatement in very abstract terms of some aspects of the relationship between the larger society or corporate body and its primary groups. The classification of the properties of objects at which we arrived in 1950 was a necessary condition for my discernment of the distinctiveness of the primordial, the personal, the sacred, and the civil. In the winter and spring of 1953, I read a lot on religious sects, heresies, monasticism, religious revivals, conversionphenomena which had interested me for many years. My studies of Marxism and the communist movement had begun when I was an undergraduate and had been encouraged in the 1930s by Robert Park and by Harold Lasswell. Park, on the basis of a seminar paper10 which I had delivered in his course on collective behavior, had in fact invited me to take up an assistantship under his supervision in order to write a book on the 9. This was a generalization of the schemes toward which I had moved in the late 1930s in several papers on the criteria on the basis of which status or deference were accorded. The paper for The Negro in America was one of these. The work which we did together at Harvard was an extension of this mode of analysis to relationships other than those of status. Originally, I was driven to this by the unsatisfactoriness of Weber's treatment of classes and status groups and the utter disregard for the phenomenon of status in the Marxian literature. On the positive side, I was helped by reading Proust's A la Recherche du temps perdu. 10. This was based mainly on the careful reading of the Daily Worker, to which I subscribed at that time. Sombart and Arthur Rosenberg were my guiding stars. The paper was formed around the contrast between the total and comprehensive electoral platforms of the Communist and Social Democratic parties, primarily in New York and more generally in the United States. It was my first effort to formulate my conception of ideology.

Introduction xxvii communist movement He thought my analysis in that paper fitted into his own ideas about social movements. Lasswell encouraged me simply by his own interest in such mattershe was the only teacher at the University of Chicago who was at home among the famous European figures, such as Weber, Michels, Pareto, Sombart, who seemed to me in my earlier years to be the repositories of whatever a young person of intellectual seriousness ought to know. The political events of the 1930s in Europe and America and the associated rash of fellow-traveling among American and European intellectuals of the time inevitably kept my interest in these matters on the alert. Thefieldworkwhich I did on the North Side of Chicago among nativist and pro-Nazi groups enabled me to appreciate the sensitivity about sharply defined boundaries which I later came to see as characteristic of ideological primary groups. My studies of Germany during the war increased my awareness of the relationship between the demand for disjunctive boundaries in certain types of small groups and their commitment to transform the larger society in all aspects in the light of an exigent ideal. It was, however, only when I tried in the early 1950s to put together what I had learned about primary groups in armies, what I had read in the then prospering field of industrial sociology, and what I had observed and studied about religious and political sects, that I saw that I was dealing with several sorts of things which overlapped in some respects and which differed profoundly in others. I learned a lot from thinking and reading about what was meant by Christian love, which I concluded was different from both erotic love and personal affection. I was helped in this by reading Arthur Darby Nock's Conversion, Anders Nygren's Agape and Eros, Monsignor Martin D'Arcy's The Heart and Mind of Love, Father Ronald Knox's Enthusiasm, and Denis de Rougemont's L 'Amour dans VOccident. Knox's book was especially rich. What was beginning to emerge from these diverse explorations was the need to recognize that primary groups in which the members were attached to each other as the bearers of certain beliefs, were different from those in which attachments focused on personal qualities, qualities of disposition, or properties constituted by a presumedly common biological origin or territorial location. The primordial, the sacred, the personal, and the civil were beginning to emerge as separate modes of attachment But it all remained rather obscure. In the spring of 1953, I presented a paper at the Psychology Club of University College, London, on "Private Man, Political Man, Ideological Man." This paper brought together in a way which I had not done previously my ideas about the variety of spheres or circles within which attachments occur and the antinomies and identities of the attachments in these diverse spheres. Although I was living in Manchester at that time, I was much occupied with Senator McCarthy and his fellowtravelers. The paper undertook to order these observations. At about the

xxviii Introduction same time I wrote another long paper on "Institutional Specialization" in which I again, from another angle, approached the dependence of civility on the pluralism of professional and institutional loyalties. As a result of these developments, I decided that my views about primary groups had to be thoroughly recast This was a time when the United States was in one of its recurrent states of enthusiasm, with unitary and unqualified loyalty to the central institutional and value systems being the main plank in the platform of the enthusiasts. "Americanism" was the standard, "Un-American" was the criterion of what was to be avoided. This enthusiasm, which at that time was given the name of McCarthyism by its critics and victims, seemed to me to present in very clearly defined form a phenomenon incompatible with the conditions of a civil societyas incompatible as the totalitarianism of communism, which was so esteemed by many intellectuals of my generation and of the one just preceding, or the totalitarianism of National Socialism. From the time of my return to the University of Chicago from Manchester in the autumn of 1953 I began to revise my earlier manuscript on primary groups. Practically nothing of it was left, because the macrosociological parts grew so disproportionately. In about fifteen months I wrote an almost wholly new manuscript of about three hundred thousand words. I called it "Love, Belief, and Civility." "Love" referred to personal ties of affection and friendship, "belief referred to ideas about sacred things and the structures in which they were embodied, and "civility" referred to the ethos and institutions concerned wtih the maintenance and adaptation of large-scale societies. The manuscript covered a tremendous range of subjects from religion and politics to intimate personal relationships. I was not at all satisfied with it and I am still not satisfied with it. That is why it is still unpublished. It did, however, bring into clearer focus the character of the beliefs and relationships which operate in the vicissitudes of the integration of society. VI The stream of my ideas in the preceding decade had flowed through a meandering course but with a persistent direction. They were the resultant of a number of loosely interconnected strands in the tradition of sociological thought; these strands were the writings of W. I. Thomas, Robert Park, Ferdinand Tonnies, George Simmel, and, above all, Max Weber. I must confess that although I had studied the works of Durkheim while I was an undergraduate, they did not have much significance for me. I was probably too callow to appreciate their depth. I came to appreciate them more after I learnedindependently of Durkheimto appreciate the place of the sacred in society. I owed a great deal to

Introduction xxix Aristotle's Politics, particularly his consideration of the causes of revolutions. Above all, Aristotle's view of man as a "political animal" remains for me one of those fundamental enigmas to which one can return time and again with the reasonable expectation of learning new things each time. The Hobbesian account of the state of nature was invaluable to me because it gave me a clear picture of what an aggregation of human beings without affectionate, erotic, or primordial ties, and without beliefs in legitimacy, would be like. But one of the intellectual figures who meant most to me in all these matters up to the early 1950s was the querulous and sagacious Frank Knight He was an often perplexing writer, with many idees fixes, but his writings in The Ethics of Competition and Other Essays and many conversations with him deepened my sense of the importance of the "rules of the game," which restricted individual and sectional self-aggrandizement and which permitted the relatively peaceful articulation of the various parts of society into a whole with distinctive properties of its own. Frank Knight was an obsessive thinker who in his youth had renounced adherence to the religious beliefs in which he had been brought up. He was by intention a rationalist who hoped without hope that men would become rational in the management of their affairs. He also knew that they would not, and this was a source of gnawing distress to him. Like any other mind of the first order in thinking about society, he had an extraordinary gift for uttering enigmatic statements of great pregnancy. He used to say that "no society would tolerate indefinitely the twisting of the tails of its sacred cows," although he was himself aware that that was just what he was doing most of the time. Stated over and over again in many very different contexts, this statement and many others made a profound impression on my efforts to understand the rules of disagreement. It was not just academic study which influenced me. Being as concerned as I was for the condition of my own country and of societies and cultures of France, Great Britain, and Germany to which I was attached and on whose literature I had been brought up intellectually, the political events of the thirties, forties, and early fifties continuously drew my attention. The Great Depression of the 1930s, something about which I learned from the experiences of my own family and of our neighbors as well as from my experience as a social worker in New York and Chicago, was the first of these events. The rise and entrenchment of National Socialism and Fascism were events of almost overwhelming significance. I learned a great deal about them and about much else that influenced my ideas from various exiled friends like Hans Speier, Karl Mannheim, Nathan Leites, Alexander von Schelting, Franz Neumann, Jacob Marschak, Leo Szilard, Michael Polanyi, and Ernst Frankel. The Second World War gave me the opportunity and the occasion to extend and deepen my knowledge of Germany and of military matters; the antagonism between the Soviet Union and the Western societies gave

xxx Introduction further material and experiences on which to ponder. "McCarthyism" was an accompaniment of this antagonism but by no means its creation. I would have criticized McCarthyism in any case, but my association with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists gave me a more immediate connection which I might otherwise have lacked. Much of the obsession with secrecy and the rancor about espionage was aroused by the existence of the atomic bomb, and nuclear physicists of the "liberal" sort were subjected to attack. The withdrawal of the privilege of secret knowledge from Robert Oppenheimer was an undignified epitome of the McCarthyite view of the world. The various legislative committees concerned with the protection of secrets and with the exposure of subversive conspiracies created much disturbance by their inquiries. They represented a type of ideological nativism as disruptive of a reasonable order of society as the totalitarianism which they allegedly sought to avert The traditional pluralism of American society was being changed by the pressure of populistic ideologists. My observations of this effort to reassert the primacy of the criterion of intense and unqualified attachment to the national society made it urgent for me to clarify my ideas about the pattern of consensus of liberal pluralistic societies. It was to draw the general lessons, theoretical and practical, of the McCarthyite rage that, in the autumn and winter of 1954-55,1 put aside "Love, Belief, and Civility," which was completed in draft. I had gone as far as I could at the time and had a series of questions whichneeded further elucidation. I turned, therefore, to draw together my views of McCarthyism, to put that disorder into a wider setting, and to contrast it with alternative modes of integration. I did not intend to produce a theoretical work: I wrote with a primarily polemical intention, but since the book was a critique of the ideological mode of integration, it was bound inevitably to be guided by my general conception of how societies work. I wrote The Torment of Secrecy in a few months and sent it to the publisher in the spring of 1955. Since it was written largely with a practical purpose, I did not take the leisurely attitude toward its publication that I did with my other writings. Nonetheless, it was a considerable advance over what I had thought previously about consensus in a highly differentiated society with many conflicts. Looking back at it later I found that in its contrast between ideological politics and pluralistic politics, it was elaborating the fundamental distinction between Gesinnungsethik arid Verantwortungsethik made by Max Weber. The power of the intellectual traditions which came together and which were extended by Max Weber was again manifesting itself in a new setting. VII At this point I went to India for an extended period. On my return, in

Introduction xxxi addition to my work on intellectuals, some of which is reprinted in the first volume of this series, I took up once more the numerous questions with which I had not dealt satisfactorily in "Love, Belief, and Civility." Much of what I have written since that time has been intended to develop particular themes or topics which seemed to me to need improvement before the larger work could be made fit for publication. One such theme was the basis of the various types of collectivities in which human beings participate. This entailed some reformulations of the work which I had done with Professor axscns_gn_ the classification of the properties of objects or orientation. The result of this was the paper on "Primordial, Personal, Sacred, and Civil Ties." "Ideology and Civility," "The Concentration and Dispersion of Charisma," and "Center and Periphery" all belong to this phase. In all these efforts I have been encouraged by the forceful way in which Professor Samuel Eisenstadt has elaborated these ideas and brought them to bear in his various works. In a more roundabout manner, however, my experiences in the study of Indian intellectuals provided me with a clue which has since proved rather fruitful, although its character and scope are still not settled. This is the idea that societies have a center to which their members orient themselves and which influences their conduct in a wide variety of ways. This notion first came to me in consequence of my observation of the" anglophilia of Indian intellectuals. The attractive powers of national center had already been touched on in the paper which I published on British intellectuals before going to India in 1955, but it had a wider significance of which I was unaware before I went to India. After I returned from India and began to analyze what I had observed there, I recalled the ecological work on metropolitan dominance done by Robert Park and Roderick McKenzie about thirty years before. The still earlier studies of Charles Galpin regarding the ecological conformation of small towns, villages, and the open country in the rural United States in the early decades of this century came back to me. An old paper by Edward Reuter on the ecology of Western expansion in the Pacific which I had read years before and which had Iain dormant in my mind came back from memory. Of course, I knew something about the expansion of Western civilization into Asia and Africa and a little about the responses of the colonized peoples. But I had never put -these scattered bits together. Now I was moved to do so. Once I had digested the concept of center and periphery in the intellectual community, its extensive applicability to the problems of the integration of society became apparent to me. The papers on "Center and Periphery" and "Society and Societies" represent this development. The notion that societies have centers and peripheries enabled me to lay to rest a troublesome aftermath of my intellectual inheritance. I have already mentioned the view, to which I was not unresponsive in the 1930s, that the urban, liberal-democratic, capitalistic society of the past