Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

TMP 8 E70

Cargado por

FrontiersDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

TMP 8 E70

Cargado por

FrontiersCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case Report www.ljm.org.

ly

Pneumonia caused by Moraxella catarrhalis in

haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.

Report of two cases and review of the literature

Al-Anazi KA1, Al-Fraih FA2, Chaudhri NA1 and Al-Mohareb FI1

(1) Section of Adult Hematology and Stem Cell Transplant,

King Faisal Cancer Centre, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre

(2) Department of Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre

Abstract: Moraxella catarrhalis is a gram negative diplococcus that causes a variety of upper and lower

respiratory tract infections. Patients with malignant, hematological disorders treated with intensive cytotoxic

chemotherapy, and recipients of various forms of haematopoietic stem cell transplant receiving

immunosuppressive agents are at high risk of developing severe infections and septic complications. Early

detection of the organism and prompt treatment with appropriate antibiotics provide both resolution of the

infection and prevention of further consequences. Two patients with haematopoietic stem cell transplant who

developed pneumonia caused by M. catarrhalis at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in

Riyadh are reported and the literature is reviewed. To our knowledge, these are the first case reports of M.

catarrhalis pneumonia in haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.

Key Words: Moraxella catarrhalis, Acute myeloid leukemia, Graft versus host disease, Stem cell transplant, Umbilical

cord blood transplant.

Introduction composed of high dose

In spite of the availability of antimicrobial agents, cytosine arabinoside. On 22/5/2005, she received

pneumonia constitutes the sixth most common a non-myeloablative, allogeneic, peripheral blood

cause of death and the number one cause of SCT. The conditioning protocol consisted of:

death from infection [1]. Pneumonia can be fludarabine and one session of total body

particularly life-threatening in the elderly, patients irradiation. She was given prophylactic antibiotic

with pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary conditions, therapy consisting of bactrim, penicillin and

in immunocompromised individuals, and in acyclovir. In addition she received prophylaxis for

pregnant women [1]. graft versus host disease (GVHD) in the form of

Infections are the most common cause of cyclosporine-A. The post-SCT course was

morbidity and mortality in patients with malignant complicated by acute GVHD of the colon, grade II,

disorders, and in haematopoietic stem cell treated with steroids, cyclosporine-A, and

transplant (SCT) recipients, despite the use of tacrolimus; Two episodes of CMV infections were

infection prophylaxis, growth factors, and newer treated with intravenous (IV) ganciclovir and

antimicrobial agents [2,3]. The main risk factors for reduced donor chimerism was managed with

development of infection in patients with malignant donor lymphocyte infusions. On 27/11/2006, the

disorders include: uncontrolled malignancy, patient was readmitted with a two week history of

cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunosuppressive low grade pyrexia and productive cough with

treatment, and immunological deficits, e.g. yellowish sputum. Physical examination revealed

hypogammaglobulinaemia and T-cell depletion [4]. reduced inspiratory volume with coarse crackles

In this category of patients, the risk of infection is over the mid and lower lung fields bilaterally.

directly proportional to the intensity and duration of Sputum culture grew beta-lactamase positive M.

cytotoxic chemotherapy and immunosuppressive catarrhalis sensitive to certriaxone, ceftazidime,

treatment [4]. cefatoxime, and cefuroxime, but resistant to

ampicillin and penicillin. Ziehl Neelsen stain and

Case Reports acid fast bacillus culture of the sputum were

Case 1: A 17 years old Saudi female was negative. Fungal cultures and aspergillus

diagnosed to have acute myeloid leukaemia galactomannan test were also negative.

(AML), M6 type, at King Faisal Specialist Hospital Cytomegalovirus antigen test and shell vial were

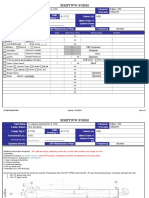

and Research Centre (KFSH&RC) in February negative. Chest X ray (CXR) showed bilateral

2005. She presented with: fever, fatigue, mucosal pulmonary infiltrates, more prominent on the left.

bleeding, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, normal Computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest

leucocytic count, few blasts on the blood film and showed nodular infiltration involving the left lower

40% blasts in the bone marrow but no palpable lobe and the lateral segment of the right lower

external lymphadenopathy or abdominal lobe (Figure 1). The patient was treated with IV

organomegaly. After receiving an ICE (idarubicin, ceftriaxone 2 grams per day for 5 days. She then

cytozar and etoposide) induction course of received oral cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily for 10

chemotherapy, she achieved the first complete more days. Following discharge, she had routine

remission of her leukaemia. Thereafter, she follow up at the SCT clinic. On 18/12/2006, chest

received a consolidation course of chemotherapy CT revealed complete resolution of nodular

Page 144 Libyan J Med, AOP: 070424

Case Report www.ljm.org.ly

pulmonary lesions. The patient was last seen at ceforuxime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime and

SCT clinic on 16/1/2007. She remained totally erythromycin, but resistant to penicillin and

asymptomatic and physical examination confirmed ampicillin. The patient received a five day course

her lung sounds were clear. Complete blood count of IV ceftriaxone (two grams per day) at the

(CBC) showed WBC: 7.74 x 10 9/L, HB: 148 g/L, oncology male treatment area. His treatement

PLT: 247 x 109/L. The patient continued on then was changed to oral cefuroxime 500 mg

tacrolimus and a tapered dose of prednisone in twice daily for one more week. Two weeks later,

addition to prophylactic penicillin, bactrim and the patient was evaluated at the outpatient clinic.

acyclovir. He was asymptomatic and physical examination

showed his chest was clear. Repeat CXR showed

Case 2: A 50 year old Saudi male was nearly complete resolution of the previous

diagnosed to have AML, M4 type, at KFSH&RC in bronchopneumonic shadows. Thereafter, the

early April, 2005. He presented with: recurrent patient remained clinically stable till he traveled to

perianal abscesses, elevated WBC count of 41 x the USA in late January, 2007 for a second

109/L with myeloblasts on blood film, anemia, alternate donor SCT.

thrombocytopenia, and 80% blast cells on bone

marrow biopsy, but no external, palpable Discussion

lymphadenopathy and no palpable, abdominal Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis (formerly

organomegaly. Initially he received ICE induction called Neisseria or Micrococcus catarrhalis) is a

chemotherapy but his leukemia was refractory to gram negative, anaerobic diplococcus frequently

this so he was then given an FA (fludarabine and found as a commensal of the upper respiratory

cytosine arabinoside) salvage course of tract [5-8]. The organism was discovered and

chemotherapy which resulted in his first complete described in some detail more than a century ago

remission of leukemia. After controlling his AML, [9]. However, M. catarrhalis has emerged as a

the patient was prepared for umbilical cord blood human pathogen in the last decade [7,9].

transplant (UCBT) since he had no compatible Recently, M. catarrhalis is considered to be the

sibling donor. He received a pre-treatment protocol third most common and most important cause of

of IV busuphan and fludarabine. He was given bronchopulmonary infections after Haemophilus

prophylactic antibiotics consisting of bactrim, influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae

acyclovir, and penicillin as well as GVHD [10,11]. Risk factors for the development of M.

prophylaxis of IV methylprednisolone and catarrhalis infections and bacteremia include:

cyclosporine-A. On 31/8/2005, the patient received advancced age; underlying chronic lung disorder

an UCBT. Post-procedure, the patient developed a e.g. bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive airway

number of complications including: Klebsiella disease, alveolitis, and pulmonary fibrosis;

pneumoniae bacteremia and septic shock which pneumoconiosis and congenital lung disease;

were treated with IV meropenem and gentamicin. sickle cell disease and immunocompromised

His fungal lung infection was treated with individuals e.g. HIV-positive patients, or those with

liposomal amphotericin-B (amBisome) and agammaglobulinaemia, granulocytopenia and

voriconazole. His prolonged pancytopenia and acute leukemia [5-17]. M. catarrhalis is linked to a

delayed recovery of blood counts were managed variety of infections including upper and lower

with growth factor and granulocyte transfusions. respiratory tract infections, bacteremia, septic

On 6/12/2005, the patient was discharged from the complications, endocarditis, meningitis, and brain

SCT unit on cyclosporine-A. The chimerism study abscess in addition to wound infections [5-9,11-

showed no engraftment, so treatment was 14,16-18]. Invasive infection due to M. catarrhalis

continued with supportive measures [growth may occur in immunocompromised individuals but

factors, packed red cell and platelet transfusions] is uncommon [5,6,8,11,18]. M. catarrhalis can lead

for the low blood counts. In October2006, the to community acquired as well as nosocomial

patient was found to have a relapse of his AML. infections [9,13,16,19]. M. catarrhalis can be

On 23/12/2006, he presented to the SCT clinic isolated from blood, nasopharyngeal secretions,

with a one week history of: fever, sore throat, and sputum, tracheal secretions, bronchoalveolar

productive cough with yellow sputum. Physical lavage, wound swabs, and tissue cultures e.g.

examination revealed reduced inspiratory volume endocardium [5,8,12-18,20,21]. Both of these

with crackles over middle and lower lung fields patients were severely immunocompromized. Both

bilaterally. CXR showed radiological evidence of had AML and were treated with two different forms

bronchopneumonia. Blood cultures were negative of SCT. They had received cytotoxic

but sputum cultures revealed growth of beta- chemotherapy and various immunosuppressive

lactamase, positive M. catarrhalis sensitive to agents. Both infections were community acquired.

Page 145 Libyan J Med, AOP: 070424

Case Report www.ljm.org.ly

The isolated organisms were cultured from sputum and UCBT have shown that infectious

while blood cultures were negative in both complications are the causes of death in

patients. The lung infection in the initial patient approximately 50% of deceased patients [27]. The

was invasive and rather severe although the dose-reduced conditioning regimens utilized in

patient was not neutropenic at the time of the non-myeloablative SCT are associated with lower

infection. Bronchopneumonia occurred during a rates of pulmonary complications [26]. The use of

period of neutropenia and after the relapse of AML steroid therapy in SCT has been shown to be a

in the second patient. leading risk factor for infectious processes [28].

The first reported case of beta-lactamase Recipients of allogeneic haematopoietic SCT have

production by M. catarrhalis was in 1976 [11]. prolonged immunodeficiency that may extend

Since that time, there has been a dramatic beyond the first year post-SCT [29]. Depletion of

increase in the frequency of beta-lactamse T-cell used in mismatched SCT reduces the

production by this organism [11]. Today, 90% or incidence of GVHD in graft recipients, but T-cell

more of the strains of M. catarrhalis deficiency in these already extensively T-cell-

are beta-lactamase producers [8-11,16,22]. depleted patients may be an additional risk factor

Consequently when M. catarrhalis is considered to for infectious complications [30]. The

be the causative organism, the choice of an reconstitution of immunity in SCT recipients is

empiric antimicrobial therapy should be a beta- often delayed in adults, patients with extensive

lactamase resistant antibiotic [23]. The strains of GVHD. and in T-cell depleted grafts [29].

M. catarrhalis are resistant to benzylpenicillin, However, the full reconstitution of the immune

ampicillin, amoxicillin and lincomycin and are system in a recipient of hematopoietic SCT is one

usually susceptible to certain cephalosporins, of the hallmarks of a successful graft [31].

macrolides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones in The first patient was expected to have a lower

addition to the combination of trimethoprim- rate of infectious complications since she had

sulfamethoxazole [8-10,15,19,24]. Ceftriaxone has received a nonmyeloablative allogeneic SCT.

highly favorable pharmacokinetics which allow However, the development of GVHD and the use

once daily dosing regimens to be employed even of various immunosuppressive agents

in the most severe infections associated with predisposed this patient to an invasive lung

cancer therapy [25]. The overall mortality related infection despite having normal neutrophilic

to bacteremic pneumonia due to M. catarrhalis is counts. The second patient had received an UCBT

about 13.3% despite the underlying disease [15]. since he encountered serious complications

Bacteremic pneumonia due to M. catarrhalis before the autologous recovery of his blood counts

requires prompt treatment to prevent the and had not had a successful graft. His immunity

development of serious organ complications such continued to be depressed due to a relapse of his

as endocarditis [18]. However, appropriate leukemia and since he was neutropenic at the

antimicrobial therapy can lead to clinical and time of the bronchopneumonia.

microbiological cure in nearly all patients infected

with this organism [13]. In these two patients, both

isolates were beta-lactamase producers. Both

were treated with IV ceftriaxone followed by oral

cefuroxime. Obtaining necessary cultures and

other required testing as well as early institution of

appropriate antimicrobial therapy led not only to

the resolution of pulmonary infiltrations but also to

the prevention of further complications.

Haematopoietic SCT is associated with

pulmonary opportunistic infections and immune

mediated responses that include idiopathic

pneumonia syndrome and brochiolitis obliterans

[26]. Pulmonary complications are the most

common cause of death in SCT recipients.

Unfortunately, the majority of these complications

Figure 1: CT scan of chest showing bilateral nodular

are not diagnosed antemortem [27]. As a

pulmonary infiltration more prominent on the left side

consequence of underdiagnosis, SCT recipients Conclusion

may not receive appropriate therapy for a M. catarrhalis can cause severe and invasive

potentially treatable pulmonary complication [27]. infections in immunocompromised individuals

Autopsy findings in recipients of allogeneic SCT particularly patients with acute leukemia and

Page 146 Libyan J Med, AOP: 070424

Case Report www.ljm.org.ly

recipients of haematopoietic SCT who have been infection caused by Moraxella catarrhalis in patients with

subjected to intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy and pneumoconiosis. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1999; 73: 311-

317.

various immunosuppressive agents. Infections 18. Neumayer D, Schmidt HK, Mellwig KP, Kleikamp

caused by this organism should be treated G. Moraxella catarrhalis endocarditis, report of a case and

promptly in order to prevent sepsis and further literature review. J Heart Valve Dis 1999; 8: 114-117.

complications. 19. McGregor K, Chang BJ, Mee BJ, Riley TV.

Moraxella catarrhalis: clinical significance, antimicrobial

References susceptibility and BRO beta-lactamases. Eur J Clin

1. Waite S, Jeudy J, White CS. Acute lung infections Microbiol Infect Dis 1998; 17: 219-234.

in normal and immunocompromised hosts. Radiol Clin 20. Domingo P, Puig M, Pericas R, Mirelis B, Prats

North Am 2006; 44: 295-315. G. Moraxella catarrhalis bacterema in an

2. Neuburger S, Maschmeyer G. Update on immunocompetent adult. Scand J Infect Dis 1995; 27: 95.

management of infections in cancer patients and stem cell 21. Richards SJ, Greening AP, Enright MC, Morgan

transplant patients. Ann Hematol 2006; 85: 345-356. MG, McKenzie H. Outbreak of Moraxella catarrhalis in a

3. George B, Mathews V, Srivastava A, Chandy M. respiratory unit. Thorax 1993; 48: 91-92.

Infections among allogeneic bone marrow transplant 22. Mendes C, Marin ME, Quinones F, Sifuentes-

recipients in India. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 33: 311- Osornio J, Siller CC, Castanheira M, Zoccoli CM, Lopez H,

315. Sucari A, Rossi F, Angulo GB, Segura AJ, Starling C,

4. Smiley S, Almyroudis N, Segal BH. Epidemiology and Mimica I, Felmingham D. Antimicrobial resistance of

management of opportunistic infections in community-acquired respiratory tract pathogens recovered

immunocompromised patients with cancer. Abstr Hematol from patients in Latin America: results from the PROTEKT

Oncol 2005; 8: 20-30. Surveillance Study 1999-2000. Braz J Infect Dis 2003, 7:

5. Verduin CM, Hol C, Fleer A, van Dijk H, Belkum AV. 44-61.

Moraxella catarrhalis: from emerging to established 23. Nowak-Sadzikowska J, Heczko PB. Moraxella

pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15: 125-144. catarrhalis is an important etiologic factor in infections of

6. Ernst-Kruis MR, Rutgers MI, Revesz T, Wolfs TF, the lower bronchial tree. Pneumol Alergol Pol 1994, 62:

Fleer A, Geelen SP. Invasive infection with Moraxella 530-532.

catarrhalis in 2 children with lymphatic leukemia and 24. Richard MP, Aguado AG, Mattina R, Marre R.

granulocytopenia. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003; 147: 1126- Sensitivity to Sparfloxacin and other antibiotics of

1128. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and

7. Murphy TF. Branhamella catarrhalis: epidemiology, Moraxella catarrhalis strains isolated from adult patients

surface antigenic structure and immune response. Microbial with community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections;

Rev 1996; 62: 267-279. a European multicentre SPAR study group. Surveillance

8. Abuhammour WM, Abdel-Haq NM, Asmar BI, Dajani Programme of Antibiotic Resistance. J Antimicrob

AS. Moraxella catarrhalis bacteremia: a 10 year experience. Chemother 1998; 41: 207-214.

South Med J 1999; 92: 1071-1074. 25. Venditti M, Martino P, Viscoli C, Klastersky J.

9. Cullmann W. Moraxella catarrhalis: virulence and Ceftriaxone alone or in combination with antibiotics in the

resistance mechanisms. Med Klin 1997; 92: 162-166. management of infection in cancer patients. Clin Drug

10. Volkov IK, Katosova LK, Shcherbakova Nlu, Invest 1999; 17: 195-200.

Kliukina LP. Moraxella catarrhalis in chronic and relapsing 26. Nusair S, Breuer R, Shapira MY, Berkman N, Or

respiratory tract infections in children. Antibiot Khimioter R. Low incidence of pulmonary complications following

2004; 49: 43- 47. nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J

11. Enright MC, McKenzie H. Moraxella 2004; 23: 440-445.

(Branhamella) catarrhalis: clinical and molecular aspects of 27. Sharma S, Nadrous HF, Peters SG, Tefferi A,

a rediscovered pathogen. J Med Microbiol 1997; 46: 360- Litzow MR, Aubry MC, Afessa B. Pulmonary complications

371. in adult blood and marrow transplant recipients: autopsy

12. Babay HA. Isolation of Moraxella catarrhalis in findings. Chest 2005; 128: 1385-1392.

patients at King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh. Saudi 28. Nucci M, Andrade F, Vigorito A, Trabasso P,

Med J 2000; 21: 860-863. Aranha JF, Maiolino A, De Souza CA. Infectious

13. Manfredi R, Nanetti A, Valentini R, Chiodo F. complications in patients randomized to receive allogeneic

Moraxella catarrhalis pneumonia during HIV disease. J bone marrow or peripheral blood transplantation.

Chemother 2000; 12: 406-411. Transplant Infect Dis 2003; 5: 167-173.

14. Gray LD, Van Scoy RE, Anhalt JP, Yu PK. Wound 29. Lacerda JF. Immunologic reconstitution after

infection caused by Branhamella catarrhalis. J Clin allogeneic stem cell transplant. Acta Med Port 2004; 17:

Microbiol 1989; 27: 818-820. 471-480.

15. Collazos J, de Miguel J, Ayarza R. Moraxella 30. Daly A, McAfee S, Dey B, Colby C, Schulte L,

catarrhalis bacteremic pneumonia in adults: two cases and Yeap B, Sackstein R, Tarbell NJ, Sachs D, Sykes M,

review of the literature. Eur J Clin Micro Infect Dis 1982; 11: Spitzer TR. Nonmyeloablative bone marrow

237-240. transplantation: Infectious complications in 65 recipients of

16. Sugiyama H, Ogata E, Shimamoto Y, Koshibu Y, HLA-identical and mismatched transplants. Biol Blood

Matsumoto K, Murai K, Miyashita T, Ono Y, Nishiya H, Marrow Transplant 2003; 9: 373-382.

Kunii O, Sato T. Bacteremic Moraxella catarrhalis 31. Chao NJ, Emerson SG, Weinberg KI. Stem cell

pneumonia in a patient with immunoglobulin deficiency. J transplantation (cord blood transplants). Hematology Am

Infect Chemother 2000; 6: 61-62. Soc Hematol Edu Program 2004; 354-371

17. Omori A, Yoshida T, Furukawa K, Takahashi A,

Mochinaga S, Nagatake T. Recurrent respiratory tract

Page 147 Libyan J Med, AOP: 070424

También podría gustarte

- Fast Facts: Myelofibrosis: Reviewed by Professor Ruben A. MesaDe EverandFast Facts: Myelofibrosis: Reviewed by Professor Ruben A. MesaAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP 155 BDocumento7 páginasTMP 155 BFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Studies on Epidemic Influenza: Comprising Clinical and Laboratory InvestigationsDe EverandStudies on Epidemic Influenza: Comprising Clinical and Laboratory InvestigationsAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP FE4 ADocumento4 páginasTMP FE4 AFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP 9 B42Documento6 páginasTMP 9 B42FrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP 69 E9Documento7 páginasTMP 69 E9FrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Medscape Infectious DiseaseDocumento110 páginasMedscape Infectious DiseaseAnoop DSouzaAún no hay calificaciones

- CytomegaloDocumento3 páginasCytomegaloYusi RizkyAún no hay calificaciones

- Idcases: Matthew B. Lockwood, Juan Carlos Rico CrescencioDocumento3 páginasIdcases: Matthew B. Lockwood, Juan Carlos Rico CrescencioAlexandra GalanAún no hay calificaciones

- A Case Report of Invasive Aspergillosis in A Patient Treated With RuxolitinibDocumento3 páginasA Case Report of Invasive Aspergillosis in A Patient Treated With RuxolitinibJongga SiahaanAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP FDC2Documento4 páginasTMP FDC2FrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Rhizomucor Scedosporium: Case ReportDocumento6 páginasRhizomucor Scedosporium: Case ReportPaul ColburnAún no hay calificaciones

- Exacerbation of Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome After Treatment of Localized Cancer-A Report of Two CasesDocumento5 páginasExacerbation of Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome After Treatment of Localized Cancer-A Report of Two Casesloshaana105Aún no hay calificaciones

- Lesoes Cisticas HIVDocumento5 páginasLesoes Cisticas HIVAndrey Barbosa PimentaAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP C0 BADocumento12 páginasTMP C0 BAFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Antifungal Catheter Lock Therapy 1Documento8 páginasAntifungal Catheter Lock Therapy 1Dakota YamashitaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fatal 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) in A Bone Marrow Transplant RecipientDocumento6 páginasFatal 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) in A Bone Marrow Transplant RecipientAntonioAún no hay calificaciones

- Management of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Hematology Patients: A Review of 87 Consecutive Cases at A Single InstitutionDocumento10 páginasManagement of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Hematology Patients: A Review of 87 Consecutive Cases at A Single Institutionsyafira nur khafifaAún no hay calificaciones

- A 65-Year-Old Man Came To The Emergency Department Via Ambulance - Relatives Accompanied The Patient and Described A 1-Day History of FeverDocumento43 páginasA 65-Year-Old Man Came To The Emergency Department Via Ambulance - Relatives Accompanied The Patient and Described A 1-Day History of FeverandriopaAún no hay calificaciones

- Severe Systemic Cytomegalovirus Infection in An Immunocompetent Patient Outside The Intensive Care Unit: A Case ReportDocumento4 páginasSevere Systemic Cytomegalovirus Infection in An Immunocompetent Patient Outside The Intensive Care Unit: A Case ReportSebastián Garay HuertasAún no hay calificaciones

- A Case Report On Sickle Cell Disease With Hemolyti PDFDocumento4 páginasA Case Report On Sickle Cell Disease With Hemolyti PDFAlhaji SwarrayAún no hay calificaciones

- Lowenthal 1996Documento7 páginasLowenthal 1996Araceli Enríquez OvandoAún no hay calificaciones

- J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis: SciencedirectDocumento6 páginasJ Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis: SciencedirectDian Putri NingsihAún no hay calificaciones

- Nebulized Colistin in The Treatment of Pneumonia Due To Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas AeruginosaDocumento4 páginasNebulized Colistin in The Treatment of Pneumonia Due To Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas AeruginosaPhan Tấn TàiAún no hay calificaciones

- Mycobacterium Other Than Tuberculosis (MOTT) Infection: An Emerging Disease in Infliximab-Treated PatientsDocumento4 páginasMycobacterium Other Than Tuberculosis (MOTT) Infection: An Emerging Disease in Infliximab-Treated PatientsFahmi Afif AlbonehAún no hay calificaciones

- Severe TuberculosisDocumento4 páginasSevere TuberculosisAdelia GhosaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Rare Case of S. maltophilia EndocarditisDocumento3 páginasRare Case of S. maltophilia EndocarditisArturo Martí-CarvajalAún no hay calificaciones

- Background: Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) Consists of 2Documento14 páginasBackground: Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) Consists of 2readyboy89Aún no hay calificaciones

- Infectious Disease Questions/Critical Care Board ReviewDocumento5 páginasInfectious Disease Questions/Critical Care Board ReviewAzmachamberAzmacareAún no hay calificaciones

- Carbapeneme PDFDocumento5 páginasCarbapeneme PDFdoxelaudioAún no hay calificaciones

- Multiple Cavitary Lung Lesions in An Adolescent - Case Report of A Rare Presentation of Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin LymphomaDocumento4 páginasMultiple Cavitary Lung Lesions in An Adolescent - Case Report of A Rare Presentation of Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin LymphomaManisha UppalAún no hay calificaciones

- Thromboembolic Complications After Splenectomy For Hematologic DiseasesDocumento5 páginasThromboembolic Complications After Splenectomy For Hematologic DiseasesDipen GandhiAún no hay calificaciones

- Lungs MCQDocumento10 páginasLungs MCQMuhammad Mudassir SaeedAún no hay calificaciones

- Primary Malignant Melanoma of The TracheDocumento93 páginasPrimary Malignant Melanoma of The TracheMikmik bay BayAún no hay calificaciones

- Staphy 2Documento5 páginasStaphy 2Alexandra MariaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial SepsisDocumento16 páginasPancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial Sepsisiamralph89Aún no hay calificaciones

- AML Presenting With TBDocumento10 páginasAML Presenting With TBshahzadAún no hay calificaciones

- TMP 103 EDocumento4 páginasTMP 103 EFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Megacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportDocumento6 páginasMegacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportgayutAún no hay calificaciones

- Under Our Very Eyes: Clinical Problem-SolvingDocumento6 páginasUnder Our Very Eyes: Clinical Problem-SolvingMauricio MerancioAún no hay calificaciones

- Ofy 038Documento5 páginasOfy 038Rosandi AdamAún no hay calificaciones

- Managing Hemato Oncology Patients in EdDocumento6 páginasManaging Hemato Oncology Patients in EdjprakashjjAún no hay calificaciones

- Stenotrophomonas. Maltophilia - A Rare Cause of Bacteremia in A Patient of End Stage Renal Disease On Maintenance HemodialysisDocumento3 páginasStenotrophomonas. Maltophilia - A Rare Cause of Bacteremia in A Patient of End Stage Renal Disease On Maintenance HemodialysisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Computed Tomography Findings of Community-Acquired Immunocompetent Patient: A Case ReportDocumento4 páginasComputed Tomography Findings of Community-Acquired Immunocompetent Patient: A Case ReportDenta HaritsaAún no hay calificaciones

- Elizabeth King I ADocumento3 páginasElizabeth King I AAlba UrbinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chi Et Al - 2013 - An Update On Pulmonary Complications of Hematopoietic Stem Cell TransplantationDocumento10 páginasChi Et Al - 2013 - An Update On Pulmonary Complications of Hematopoietic Stem Cell TransplantationRutvik ShahAún no hay calificaciones

- Acute Epiglottitis in The Immunocompromised Host: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocumento5 páginasAcute Epiglottitis in The Immunocompromised Host: Case Report and Review of The Literaturerosandi sabollaAún no hay calificaciones

- 45-Year-Old Man With Shortness of Breath, Cough, and Fever DiagnosisDocumento7 páginas45-Year-Old Man With Shortness of Breath, Cough, and Fever DiagnosisFluffyyy BabyyyAún no hay calificaciones

- Sepsis in Post Transplant Patients: DR - Hina Aamir Abbasi SiutDocumento33 páginasSepsis in Post Transplant Patients: DR - Hina Aamir Abbasi SiutSandhi PrabowoAún no hay calificaciones

- SarsCov2 Hodjkin LymphomaDocumento1 páginaSarsCov2 Hodjkin LymphomaGaspard de la NuitAún no hay calificaciones

- F - CMCRep 1 Assy Et Al - 1405Documento2 páginasF - CMCRep 1 Assy Et Al - 1405faegrerh5ju75yu34yAún no hay calificaciones

- CASE REPORT COMPETITION With Identifying FeaturesDocumento12 páginasCASE REPORT COMPETITION With Identifying FeaturesJoel Cesar AtinadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Recurrent Pneumonia Caused by Rare Granular Cell TumorDocumento7 páginasRecurrent Pneumonia Caused by Rare Granular Cell TumorJoshua MendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Crim Em2013-948071Documento2 páginasCrim Em2013-948071m.fahimsharifiAún no hay calificaciones

- PIIS0012369215421269Documento2 páginasPIIS0012369215421269chicyAún no hay calificaciones

- Respiratory Medicine CME: Lancelot Mark Pinto, Arpan Chandrakant Shah, Kushal Dipakkumar Shah, Zarir Farokh UdwadiaDocumento3 páginasRespiratory Medicine CME: Lancelot Mark Pinto, Arpan Chandrakant Shah, Kushal Dipakkumar Shah, Zarir Farokh UdwadiaLintang SuroyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading ComprehensionDocumento3 páginasReading ComprehensionYina MariaAún no hay calificaciones

- Hemoptysis in A Healthy 13-Year-Old Boy: PresentationDocumento5 páginasHemoptysis in A Healthy 13-Year-Old Boy: PresentationluishelAún no hay calificaciones

- Lee Et Al 2001 Case Report Meningococcal MeningitisDocumento3 páginasLee Et Al 2001 Case Report Meningococcal MeningitisAsmae OuissadenAún no hay calificaciones

- Pi Is 1083879118313909Documento2 páginasPi Is 1083879118313909Ljc JaslinAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp80F6 TMPDocumento24 páginastmp80F6 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp6382 TMPDocumento8 páginastmp6382 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp3CAB TMPDocumento16 páginastmp3CAB TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpCE8C TMPDocumento19 páginastmpCE8C TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp60EF TMPDocumento20 páginastmp60EF TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF3B5 TMPDocumento15 páginastmpF3B5 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF178 TMPDocumento15 páginastmpF178 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpEFCC TMPDocumento6 páginastmpEFCC TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp6F0E TMPDocumento12 páginastmp6F0E TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpE7E9 TMPDocumento14 páginastmpE7E9 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpFFE0 TMPDocumento6 páginastmpFFE0 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpC0A TMPDocumento9 páginastmpC0A TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmp1a96 TMPDocumento80 páginasTmp1a96 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmpa077 TMPDocumento15 páginasTmpa077 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpF407 TMPDocumento17 páginastmpF407 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpE3C0 TMPDocumento17 páginastmpE3C0 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp37B8 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp37B8 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp72FE TMPDocumento8 páginastmp72FE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpA0D TMPDocumento9 páginastmpA0D TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpD1FE TMPDocumento6 páginastmpD1FE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp998 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp998 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp8B94 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp8B94 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp4B57 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp4B57 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp9D75 TMPDocumento9 páginastmp9D75 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Tmp75a7 TMPDocumento8 páginasTmp75a7 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpB1BE TMPDocumento9 páginastmpB1BE TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmpC30A TMPDocumento10 páginastmpC30A TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp2F3F TMPDocumento10 páginastmp2F3F TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp27C1 TMPDocumento5 páginastmp27C1 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- tmp3656 TMPDocumento14 páginastmp3656 TMPFrontiersAún no hay calificaciones

- Readers TheatreDocumento7 páginasReaders TheatreLIDYAAún no hay calificaciones

- Computer Conferencing and Content AnalysisDocumento22 páginasComputer Conferencing and Content AnalysisCarina Mariel GrisolíaAún no hay calificaciones

- PAASCU Lesson PlanDocumento2 páginasPAASCU Lesson PlanAnonymous On831wJKlsAún no hay calificaciones

- APPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationDocumento1 páginaAPPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationsekkharAún no hay calificaciones

- Pervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire DalmynDocumento5 páginasPervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire Dalmynyorku_anthro_confAún no hay calificaciones

- Category Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiDocumento565 páginasCategory Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiJohn DowAún no hay calificaciones

- Merah Putih Restaurant MenuDocumento5 páginasMerah Putih Restaurant MenuGirie d'PrayogaAún no hay calificaciones

- 12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumDocumento9 páginas12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumRaja KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Intentional Replantation TechniquesDocumento8 páginasIntentional Replantation Techniquessoho1303Aún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding Abdominal TraumaDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding Abdominal TraumaArmin NiebresAún no hay calificaciones

- Biomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesDocumento9 páginasBiomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesAna Elisa AchilesAún no hay calificaciones

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocumento11 páginas01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoAún no hay calificaciones

- Intracardiac Echo DR SrikanthDocumento107 páginasIntracardiac Echo DR SrikanthNakka SrikanthAún no hay calificaciones

- Second Year Memo DownloadDocumento2 páginasSecond Year Memo DownloadMudiraj gari AbbaiAún no hay calificaciones

- MAY-2006 International Business Paper - Mumbai UniversityDocumento2 páginasMAY-2006 International Business Paper - Mumbai UniversityMAHENDRA SHIVAJI DHENAKAún no hay calificaciones

- IC 4060 Design NoteDocumento2 páginasIC 4060 Design Notemano012Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesDocumento3 páginasThe Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesMax Craiven Rulz LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Algebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsDocumento8 páginasAlgebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsGambit KingAún no hay calificaciones

- Iron FoundationsDocumento70 páginasIron FoundationsSamuel Laura HuancaAún no hay calificaciones

- Risc and Cisc: Computer ArchitectureDocumento17 páginasRisc and Cisc: Computer Architecturedress dressAún no hay calificaciones

- Network Profiling Using FlowDocumento75 páginasNetwork Profiling Using FlowSoftware Engineering Institute PublicationsAún no hay calificaciones

- Chemistry Sample Paper 2021-22Documento16 páginasChemistry Sample Paper 2021-22sarthak MongaAún no hay calificaciones

- Motivation and Emotion FinalDocumento4 páginasMotivation and Emotion Finalapi-644942653Aún no hay calificaciones

- Solar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringDocumento67 páginasSolar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringMardi RahardjoAún no hay calificaciones

- MID Term VivaDocumento4 páginasMID Term VivaGirik BhandoriaAún no hay calificaciones

- Simptww S-1105Documento3 páginasSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranAún no hay calificaciones

- Com 10003 Assignment 3Documento8 páginasCom 10003 Assignment 3AmandaAún no hay calificaciones

- TOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFDocumento16 páginasTOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFdevvy anneAún no hay calificaciones

- COVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictDocumento30 páginasCOVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictNaveen TextilesAún no hay calificaciones

- MCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Documento0 páginasMCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Sharat Chandra100% (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (402)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDe EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (4)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (13)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDe EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearDe EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (23)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeAún no hay calificaciones

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDe EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (3)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (78)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDe EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsAún no hay calificaciones

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDe EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (169)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesDe EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (34)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDe EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsAún no hay calificaciones

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDe EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (31)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementDe EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (40)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (110)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDe EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (253)

- Secure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeDe EverandSecure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (17)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDe EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (327)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDe EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (44)