Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Case Study

Cargado por

vishal_000Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case Study

Cargado por

vishal_000Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case study: Krafts takeover of Cadbury

The story In 2009, US food company Kraft Foods launched a hostile bid for Cadbury, the UK-listed chocolate maker. As became clear almost exactly two years later in August 2011, Cadbury was the final acquisition necessary to allow Kraft to be restructured and indeed split into two companies by the end of 2012: a grocery business worth approximately $16bn; and a $32bn global snacks business. Kraft needed Cadbury to provide scale for the snacks business, especially in emerging markets such as India. The challenge for Kraft was how to buy Cadbury when it was not for sale. The history Kraft itself was the product of acquisitions that started in 1916 with the purchase of a Canadian cheese company. By the time of the offer for Cadbury, it was the worlds second-largest food conglomerate, with seven brands that each generated annual revenues of more than $1bn. Cadbury, founded by John Cadbury in 1824 in Birmingham, England, had also grown through mergers and demergers. It too had recently embarked on a strategy that was just beginning to show results. Ownership of the company was 49 per cent from the US, despite its UK listing and headquarters. Only 5 per cent of its shares were owned by short-term traders at the time of the Kraft bid. The challenge Not only was Cadbury not for sale, but it actively resisted the Kraft takeover. Sir Roger Carr, the chairman of Cadbury, was experienced in takeover defences and immediately put together a strong defensive advisory team. Its first act was to brand the 745 pence-per-share offer unattractive, saying that it fundamentally undervalued the company. The team made clear that even if the company had to succumb to an unwanted takeover, almost any other confectionery company (Nestl, Ferrero and Hershey were all mentioned) would be preferred as the buyer. In addition, Lord Mandelson, then the UKs business secretary, publicly declared that the government would oppose any buyer who failed to respect the historic confectioner. The response Cadburys own defence documents stated that shareholders should reject Krafts offer because the chocolate company would be absorbed into Krafts low growth conglomerate business model an unappealing prospect that sharply contrasts with the Cadbury strategy of a pure play confectionery company. Little did Cadburys management know that Krafts plan was to split in two to eliminate its conglomerate nature and become two more focused businesses, thereby creating more value for its shareholders. The result The Cadbury team determined that a majority of shareholders would sell at a price of roughly

830 pence a share. A deal was struck between the two chairmen on January 18 2010 at 840 pence per share plus a special 10 pence per share dividend. This was approved by 72 per cent of Cadbury shareholders two weeks later. The key lessons In any takeover, especially a cross-border deal in which the acquired company is as well known as Cadbury was in the UK, the transaction will be front-page news. In this case, it was the lead business story for at least four months. Fortunately, this deal had no monopoly or competition issues, otherwise those regulators could also have been involved. But aside from any regulators, most other commentators will largely be distractions. It is important for the acquiring companys management and advisers to stay focused on the deal itself and the real decision-makers the shareholders of the target company. As this deal demonstrates, these shareholders may not (and often will not) be the long-term traditional owners of the target company stock, but rather very rational hedge funds and other arbitrageurs (in Cadburys case, owning 31 per cent of the shares at the end), who are swayed only by the offer price and how quickly the deal can be completed. Other stakeholders may have legitimate concerns that need to be addressed but this can usually be done after the deal is completed, as Kraft did. The writer is a professor in the practice of finance at Cass Business School, where he is also the director of the M&A research centre.

También podría gustarte

- Mi Kon Aahe PDFDocumento62 páginasMi Kon Aahe PDFpsakhareAún no hay calificaciones

- New Name FormDocumento1 páginaNew Name FormTimothy BrownAún no hay calificaciones

- Maharastra 2008 09Documento58 páginasMaharastra 2008 09vishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

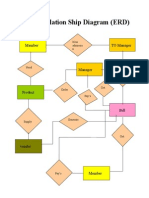

- ErdDocumento2 páginasErdvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- The 1955 Romance Comics Trial - Adelaide Comics and Books (PDFDrive)Documento290 páginasThe 1955 Romance Comics Trial - Adelaide Comics and Books (PDFDrive)vishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Oogle Play Books - Ebooks, Audiobooks, and Comics - Apps ..Documento2 páginasOogle Play Books - Ebooks, Audiobooks, and Comics - Apps ..vishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- E-R Diagram:-: Admission RejectDocumento1 páginaE-R Diagram:-: Admission Rejectvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- 7 P'sDocumento4 páginas7 P'svishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Wildlife Protection ActDocumento7 páginasThe Wildlife Protection Actvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ozone DepletionDocumento6 páginasOzone Depletionvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- 4.37 Management MMS Sem III & IVDocumento135 páginas4.37 Management MMS Sem III & IVGayatri MudaliarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Capacity and Willingness To DevelopDocumento2 páginasThe Capacity and Willingness To Developvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- District Industries CentreDocumento7 páginasDistrict Industries Centrevishal_000100% (1)

- Report of The Committee Appointed by The SEBI On Corporate Governance Under The Chairmanship ofDocumento9 páginasReport of The Committee Appointed by The SEBI On Corporate Governance Under The Chairmanship ofvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Cs 1Documento3 páginasCs 1vishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- District Industries CentreDocumento7 páginasDistrict Industries Centrevishal_000100% (1)

- 1 IntrodlogDocumento47 páginas1 IntrodlogKirit KothariAún no hay calificaciones

- Businesstobusinessmarketing PPT 120914091756 Phpapp01Documento48 páginasBusinesstobusinessmarketing PPT 120914091756 Phpapp01vishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Types of ResearchDocumento4 páginasTypes of Researchvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Resume: Career ObjectiveDocumento1 páginaResume: Career Objectivevishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Brand ValuationDocumento1 páginaWhat Is Brand Valuationvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Case StudyDocumento2 páginasCase Studyvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Delhi PressDocumento2 páginasDelhi Pressvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing StrategyDocumento99 páginasMarketing Strategymahtolalan100% (1)

- WRL2454 TMPDocumento9 páginasWRL2454 TMPvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rescued DocumentDocumento1 páginaRescued Documentvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- WRL3553 TMPDocumento7 páginasWRL3553 TMPvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Inspiring Story of Suresh KamathDocumento4 páginasThe Inspiring Story of Suresh Kamathvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ibsar Institute of Management Studies (Iims), KarjatDocumento7 páginasIbsar Institute of Management Studies (Iims), Karjatvishal_000Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2102)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- PDF 20699Documento102 páginasPDF 20699Jose Mello0% (1)

- Periodical Increment CertificateDocumento1 páginaPeriodical Increment CertificateMD.khalil100% (1)

- Acctg 14 - MidtermDocumento5 páginasAcctg 14 - MidtermRannah Raymundo100% (1)

- Accounting QuestionsDocumento16 páginasAccounting QuestionsPrachi ChananaAún no hay calificaciones

- MBridgeDocumento50 páginasMBridgeTsila SimpleAún no hay calificaciones

- Ahi Evran Sunum enDocumento26 páginasAhi Evran Sunum endenizakbayAún no hay calificaciones

- Lapid V CADocumento11 páginasLapid V CAChami YashaAún no hay calificaciones

- Application Form ICDFDocumento2 páginasApplication Form ICDFmelanie100% (1)

- Mystique-1 Shark Bay Block Diagram: Project Code: 91.4LY01.001 PCB (Raw Card) : 12298-2Documento80 páginasMystique-1 Shark Bay Block Diagram: Project Code: 91.4LY01.001 PCB (Raw Card) : 12298-2Ion PetruscaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cameron Residences - Official Project Brief - 080719Documento47 páginasCameron Residences - Official Project Brief - 080719neil dAún no hay calificaciones

- Lateral Pile Paper - Rev01Documento6 páginasLateral Pile Paper - Rev01YibinGongAún no hay calificaciones

- 007 G.R. No. 162523 November 25, 2009 Norton Vs All Asia BankDocumento5 páginas007 G.R. No. 162523 November 25, 2009 Norton Vs All Asia BankrodolfoverdidajrAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesun 2009-07-09 Page05 Ex-Pka Director Sues Nine For rm11mDocumento1 páginaThesun 2009-07-09 Page05 Ex-Pka Director Sues Nine For rm11mImpulsive collectorAún no hay calificaciones

- Electrical Engineering: Scheme of Undergraduate Degree CourseDocumento2 páginasElectrical Engineering: Scheme of Undergraduate Degree CourseSuresh JainAún no hay calificaciones

- W01 358 7304Documento29 páginasW01 358 7304MROstop.comAún no hay calificaciones

- Train Details of New DelhiDocumento94 páginasTrain Details of New DelhiSiddharth MohanAún no hay calificaciones

- CS8792 CNS Unit5Documento17 páginasCS8792 CNS Unit5024CSE DHARSHINI.AAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading #11Documento2 páginasReading #11Yojana Vanessa Romero67% (3)

- Angiomat Illumena MallinkrodtDocumento323 páginasAngiomat Illumena Mallinkrodtadrian70% (10)

- Geometric Latent Diffusion ModelDocumento18 páginasGeometric Latent Diffusion ModelmartaAún no hay calificaciones

- RRLDocumento4 páginasRRLWen Jin ChoiAún no hay calificaciones

- Rules and Regulations Governing Private Schools in Basic Education - Part 2Documento103 páginasRules and Regulations Governing Private Schools in Basic Education - Part 2Jessah SuarezAún no hay calificaciones

- Advantages, Disadvantages and Applications of Regula Falsi MethodDocumento12 páginasAdvantages, Disadvantages and Applications of Regula Falsi MethodMd Nahid HasanAún no hay calificaciones

- Contribution of Science and Technology To National DevelopmentDocumento2 páginasContribution of Science and Technology To National DevelopmentAllan James DaumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Abstract 2 TonesDocumento8 páginasAbstract 2 TonesFilip FilipovicAún no hay calificaciones

- Macaw Recovery Network - Výroční Zpráva 2022Documento20 páginasMacaw Recovery Network - Výroční Zpráva 2022Jan.PotucekAún no hay calificaciones

- Aquamimicry: A Revolutionary Concept For Shrimp FarmingDocumento5 páginasAquamimicry: A Revolutionary Concept For Shrimp FarmingMarhaendra UtamaAún no hay calificaciones

- Annexure - IV (SLD)Documento6 páginasAnnexure - IV (SLD)Gaurav SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Art Research Paper OutlineDocumento8 páginasArt Research Paper Outlinefyr90d7m100% (1)

- File 1379580604 PDFDocumento9 páginasFile 1379580604 PDFMuhammad Salik TaimuriAún no hay calificaciones