Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Investigation Into The Occupational Lives of Healthy Older People Through Their Use of Time

Cargado por

Aditya KumarTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Investigation Into The Occupational Lives of Healthy Older People Through Their Use of Time

Cargado por

Aditya KumarCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal (2010) 57, 2433

doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00845.x

Research Article

Investigation into the occupational lives of healthy older people through their use of time

Rachel Chilvers,1 Susan Corr2 and Hayley Singlehurst2

1Adult Care Services, Hertfordshire County Council, Stevenage, and 2The Division of Occupational Therapy, School of Health, The University of Northampton, Northampton, UK

Background aim: Older people are one of the largest groups using health-care services; therefore, it is important for occupational therapists to have an understanding of their occupational lives. Temporality is a key element of occupation, yet little research exists regarding older people and time use, despite the considerable temporal adjustments taking place at this lifestage. The aim of this study was to identify the occupational lives of healthy older people through the activities they undertake in a 24-hour period. Method: Data analysis of time-use diaries from 90 older UK residents (aged 6085 years) who considered themselves to be healthy was undertaken, using 15 activity codes and three pre-coded terms: necessary, enjoyable and personal. Results: The participants spent most of their time sleeping and resting (34%), followed by performing domestic activities (13%), watching television, listening to the radio or music, or using computers (11%), eating and drinking (9%) and socialising (6%). Enjoyable activities occupied most of their time (42% of the day), followed by necessary (34%) and personal activities (16%). Conclusion: These data contribute to the growing evidence base regarding older people as occupational beings, indicating that they are a diverse group of individuals who are meeting their needs with dynamic, positive activities. This highlights the importance of a client-centred approach to occupational therapy, as it enables the clients

to have choice, control and diversity in their activities when meeting their needs. KEY WORDS healthy older people, occupational lives, time use.

Introduction

Older people are one of the largest client groups using health-care services in the United Kingdom, and demographic forecasts suggest that this will increase (Soule et al., 2005). In Western societies, much of life is governed by time, which strongly inuences individuals occupations (Farnworth, 2004), whereas the World Health Organization (2002) recognises time use as a measure of health and disability. However, little literature exists regarding older peoples time use from an occupational perspective. Qualitative research suggests that for health and wellbeing, older people need to spend their time engaged in meaningful occupations (Rudman, Cook & Polatajko, 1996), and the Ofce for National Statistics (ONS, 2005) publishes time-use survey data regarding specic activities performed by older people. However, neither describes both the activities performed and their meaning.

Background

Successful ageing

Several theories exist concerning successful ageing; from disengagement theory, suggesting that individuals naturally withdraw from society (Cumming & Henry, 1961), to activity theory, suggesting that the more activities engaged in, the greater the life satisfaction (Havighurst, 1961). Occupational therapy literature regards this lifestage as a challenging occupational phase where older people are free to become more fully themselves (Hugman, 1999). Successful ageing as a theory has three components: good physical health, maintenance of cognitive abilities and engagement in social and productive activities (Rowe & Kahn, 1997). Thus it appears that a tension exists between old age as a time of loss and adjustment, and as a time for development and growth. Nonetheless,

Rachel Chilvers BSc (Hons); Occupational Therapist. Susan Corr PhD, MPhil, Dip MEDEd, Dip COT; Reader in Occupational Science. Hayley Singlehurst BSc (Hons). Correspondence: Rachel Chilvers, Hertfordshire County Council, Locality Team, 2nd Floor SFAR, Farnham House, Six Hills Way, Stevenage SG1 2FQ, UK. Email: rachel. chilvers@hertscc.gov.uk Accepted for publication 14 November 2009.

C

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Journal compilation Occupational Therapists

OCCUPATIONAL LIVES OF HEALTHY OLDER PEOPLE

25 which some found to be empty of meaning, missing the structure and challenges that employment had provided (Jonsson et al.).

activity and health emerge as important factors. Evidence from older people identies a strong correlation between successful ageing and the absence of disability, and a moderate association among successful ageing, physical activity and social contacts (Depp & Jeste, 2006).

Time use, activity and older people

The qualitative studies do not explore the specic activities older people engage in. In contrast, quantitative timeuse data detail activities performed in a dened time period, such as a single day (ONS, 2005). This is of interest as activities take place over a nite period of time that can be measured and therefore comparisons between groups can be drawn. Hence, analysis of time use gives an insight into the ow of activities inherent in occupations. The ONS completed a household survey using pre-coded diaries, covering a single day (previous day recalled, day of week recorded) of 4941 individuals in 2005. The analysis of the data revealed that older people spend the largest proportion of their time sleeping, followed by performing housework, watching television and eating and drinking (ONS). This survey did not specically consider only those who deemed themselves healthy. Additionally, from an occupational perspective, the study of individuals activities lacks the dimension of meaning. However, activities can be categorised as self-care, leisure and productivity (CAOT, 2002). These domains are interrelated and individual to each person at any given point in time. This categorisation can be viewed as being too simplistic, confusing or inappropriate for older people (Rudman et al., 1996). Many denitions of occupational balance, often viewed as an indicator of wellbeing and health, have a temporal aspect such as time spent between the performance areas of self-care, leisure and productivity (Backman, 2004; CAOT). Turner (1997; cited in Turner, 2002) found that for healthy adults, the division of time was 33% in sleep, 36% in productive activities, 19% in leisure and 11% in self-care. There have been few time-use studies in the occupational therapy literature to describe older peoples occupational engagement. Stanley (1995) asked 58 randomly selected older Australians, aged 7089 years, to complete a 48-hour time diary, a life satisfaction scale and a questionnaire. The percentage of each four-hour period spent in valued occupations over the previous two days was also requested. The latter was completed by less than half of the participants, suggesting that placing a value on an occupation in this way may have been too difcult. This and the questionnaire have no proven reliability or validity. It was found that older people were more likely to spend time sleeping, followed by engaging in passive leisure, personal care, housework and social activities. Fricke and Unsworth (2001) conrmed that older people spent most time sleeping, followed by engaging in passive leisure, personal care and housework. They investigated time use among 33 community-dwelling, older Australians, aged 6695 years, attending a community centre. A 24-hour time diary was used and the

Occupation, health and time

Occupational therapists believe that occupations are essential for health (Wilcock, 1998). A review of 23 studies of people without disabilities by Law, Steinwender and Leclair (1998) found moderate to strong evidence of a relationship between occupation, health and wellbeing, where the removal of occupation had a detrimental effect. The hypothesis that occupation causes health and wellbeing is difcult to establish as it can be argued that healthy people engage in more occupations because of their good health and not that their occupations cause it. However, Clark et al. (1997) demonstrated how occupation can improve health and wellbeing, through a randomised control trial of 361 multi-cultural, healthy, elderly Americans aged 60 years or older who were living independently in the community. They found that only participants receiving occupational therapy interventions showed statistically signicant improvements in overall health, life satisfaction, mental health and physical and social functioning. Occupational therapists have given the term occupation a wide-reaching, multidimensional and complex meaning, encompassing all the things people do to occupy themselves. Models such as the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT), 2002) together with denitions such as that proposed by Creek (2004) suggest that occupations can be categorised as self-care, productivity or leisure. Occupations are comprised of activities, which in turn are comprised of tasks, forming a hierarchy on which everyday life is constructed (Creek). Occupations and time are inextricably linked. Purposeful time use was valued by the founders of occupational therapy (Meyer, 1922). However, it was not until Kielhofners (1977) seminal paper, which re-introduced the premise of a relationship between time use and wellbeing, that temporal adaptation was considered as a conceptual framework within the occupational therapy literature, and the resulting Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner, 2008) addresses time use through human habituation in the form of habits, routines and roles. Older people may be required to undertake considerable temporal adaptation, because of loss of occupations, roles and routines associated with earlier lifestages. Jonsson, Borell and Sadlo (2000), exploring the occupational transition of retirement through longitudinal qualitative studies, found that older people face a paradox. Newly retired people relished the ownership of their time, the freedom to pursue occupations of their choice and no longer being subject to role strain and time pressures. However, many had adopted a slower rhythm of life,

C

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation

26 participants were asked whether they liked each activity. A questionnaire also recorded information regarding participation in 19 instrumental activities of daily living and their importance in the preceding two weeks. The small sample, from a narrow demographic and cultural background, dominated by women (26, 78.8%), reduced the rigour and transferability of this study. It was found that the activities rated as most important were activities that did not occupy most time. Participants also found the gross concept of liking an activity inadequate to express its meaningfulness, and the results of this aspect of the study were inconclusive. This was similar to the difculties in Stanleys (1995) study when placing a value on an occupation. More recently, through their exploration of the link between time use, role participation and life satisfaction in older people, using the Activity Conguration, Role Checklist and Life Satisfaction Index-Z, McKenna, Broome and Liddle (2007) also found that the roles which older people valued did not reect the amount of time spent in them. The study comprised 195 participants from Queensland who were recruited from advertisements and, therefore, it could be argued that they were a healthier sample than the general population. The instruments used all have proven reliability and validity. However, the Activity Conguration, although it covered the previous seven days and thus captured activities that may not have occurred daily, relied on recall of half-hour time slots during that period, which may have proved difcult for participants, and consequently reduced the accuracy of the results. Nevertheless, the resulting timeuse data correlated well with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 1997), with sleep, solitary leisure, instrumental activities of daily living and social leisure occupying most time (35, 19, 13 and 11% of the day, respectively). The study concluded that older peoples activities are diverse and that increasing age did not reduce occupational or role engagement, again challenging disengagement theory and supporting occupational therapy philosophy. Additional research is needed to examine further what activities older people undertake and the reason for this; therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the occupational lives of older people who consider themselves to be healthy, through their activities and time use. Accurate, detailed knowledge of how healthy older people are spending their time can then be used to inform occupational therapists, as they enable older people to achieve control and choice when identifying their goals and priorities in a client-centred manner.

R. CHILVERS ET AL.

stand older people as occupational beings. It focussed on data collected from time-use diaries (Ball et al., 2007; Knight et al., 2007) as part of a larger study which used a mixed methodology.

Data collection

Convenience sampling was used by a cohort of rst-year occupational therapy undergraduates, each interviewing one older person, aged 6085 years, who considered themselves to be healthy (Ball et al., 2007). The older person completed a time-use diary consisting of one 24-hour period divided into 48 half-hour time slots, to provide sufcient detail without the task becoming too onerous on the participant. The day of the week was recorded (Fricke & Unsworth, 2001; Robinson, 1999). The main activity and the reason why it was being undertaken (necessary, enjoyable and personal) were recorded. Time use, studied using tools such as diaries, surveys or interviews, has been widely used by social directives and governments. The language used was straightforward, reducing potential bias (Harvey & Pentland, 1999). Time diaries have been successfully used with older people (Fricke & Unsworth, 2001; Stanley, 1995), supporting its validity and reliability in this study.

Ethical considerations

The research was approved by the School of Health Ethics Advisory Panel at the University of Northampton. Participants provided consent for participation in the study, and all diaries were anonymous and unidentiable (Ball et al., 2007; Knight et al., 2007).

Data analysis

The raw data were coded into numerical data according to activity categories (Table 1). The coding had to be consistent and evidence based, for the study to be valid and rigorous. Several coding systems exist in the public domain, and harmonisation and consistency of language are being encouraged (Eurostat, 2008). This terminology, although not necessarily the language used by occupational therapists, is well understood by the general population. Previous occupational therapy studies have adopted or adapted their coding systems from national databases such as the ABS (1997; Fricke & Unsworth, 2001); therefore, as the participants of this study were UK residents, the categories used next were derived from the UK ONS (2005), thereby enabling direct comparisons. Further coding of activities was undertaken (Table 2). A time diary was initially trialled, allowing the participants to categorise their activities as self-care, leisure or productivity, or any combination (Farnworth, 2004). This avoided the research team from prescribing the categorisation. However, the participants appeared to nd this terminology confusing. The terms were therefore replaced with personal, enjoyable and necessary, respectively. A code mixed was used where an individual regarded

C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists

Methodology

Study design

This study was part of a research programme undertaken by the University of Northampton with the aim to under-

Journal compilation

OCCUPATIONAL LIVES OF HEALTHY OLDER PEOPLE

27

TABLE 1: Coding of activities as they correlate with coding used in National Time-Use Survey, 2005 National Time-Use Survey, 2005 Code 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Activity Sleep Rest Personal care, i.e. wash dress Eating and drinking Cooking, washing up Cleaning, tidying Washing clothes Repairs and gardening Pet care Paid work Formal education Recreational study Voluntary work Caring for own children Caring for other children Caring for adults in own household Caring for adults in other household Shopping, appointments TV and videos DVDs, radio, music Reading Sports and outdoor activities Spending time with family friends at home Going out with family friends Contact with friends family Entertainment and culture Attending religious and other meetings Hobbies Using a computer Travel This study Code 1 1 2 3 4 4 4 4 5 6 6 5 7 8 9 8 8 10 11 12 5 13 13 13 13 5 5 11 14 Activity Sleep and rest Sleep and rest Personal care Eating and drinking Domestic activities Domestic activities Domestic activities Domestic activities Hobbies, sports and religious activities Paid work and formal education Paid work and formal education Hobbies, sports and religious activities Voluntary work Caring for adults Caring for other children Caring for adults Caring for adults Shopping, appointments TV and videos DVDs, radio, music, computers Reading Hobbies, sports and religious activities Social Social Social Social Hobbies, sports and religious activities Hobbies, sports and religious activities TV and videos DVDs, radio, music, computers Travel

two or more activities within a particular activity category differently. For example, cleaning may be regarded as necessary, whereas gardening may be enjoyable; yet both were recorded as domestic activities. Data were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, 1998). The number of minutes was totalled for each diary as a built-in check, to conrm precisely 1440 minutes (24 hours) was accounted for. Stability was ensured by recoding a random sample of 5% of the dataset and checking for errors. The number of errors found was divided by the total number of potential errors and converted to a percentage (97.8% accuracy; Kielhofner, 2006). Internal consistency could not be tested as, although participants may have recorded sleep as necessary at 3 am and necessary

C

TABLE 2: personal Code 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Coding of activities as necessary, enjoyable or

Necessary, enjoyable or personal Necessary Necessary and enjoyable Necessary, enjoyable and personal Necessary and personal Enjoyable Enjoyable and personal Personal Mixed

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation

28 and enjoyable at 3 pm, it may be that they regarded sleep differently at separate times of a day. Equivalence was tested using a second coder who coded and entered another randomly selected 5% of the sample. Inter-rater reliability was found to be 96.3%. All errors were corrected.

R. CHILVERS ET AL.

Over half of the group rated their health as either excellent (20, 21%) or good (31, 32%), and almost a further quarter as average (23, 24%; Table 3).

Time-use data

The participants spent most of their time sleeping and resting. This was followed by performing domestic activities, watching television and related activities, eating and drinking and socialising.

Results

Demographic data

A total of 96 students took part in the data collection and 92 diaries were received. Two diaries were incomplete and not used; therefore, 90 diaries were analysed. The participants were aged between 60 and 85 years (mean 70.08 years, SD 6.86, six missing) and comprised 27 (28%) men and 65 (68%) women, with four (4%) missing data.

TABLE 3: Number of minutes spent in each activity Activity Sleeping and resting Domestic activities TV radio music computers Eating and drinking Socialising Personal care Hobbies sports religious activities Shopping and appointments Reading Travelling Paid work and formal education Voluntary work Caring for children Caring for adults Mean 490 194 154 127 91 74 65 49 46 42 36 36 19 10

Activities most commonly participated in

All participants spent some time asleep, and eating and drinking (Fig. 1). Nearly all spent some time in personal care (88, 98%), domestic activities (85, 94%) and watching television and related activities (85, 94%). A total of 19 (21%) participants did some voluntary work, whereas only 11 (12%) did paid work (none spent time in educa-

Minimum 180 0 0 30 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Maximum 720 480 510 330 360 210 420 240 240 270 450 390 300 210

SD 88 110 108 52 91 41 85 58 51 59 107 83 57 33

% of day 34 13 11 9 6 5 5 3 3 3 3 3 1 1

100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Number who participated

es

ng

ts tm en ,s po

C

TV

/D

Activity

FIGURE 1: Number of participants who took part in each activity.

Journal compilation

C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists

ig io n Tr av Vo el l in lu g nt C ar ar Pa y in w g id or fo w k rc or hi k ld an re d n ed uc C ar a t in io g n fo ra du lts

rs te

re s

ng

re

ca

iti

in is al

g ea

pu

tiv

in

di

ki

an

dr

al

ac

om

ci

on

So

po

tic

rs

ee

,c

Pe

es

Sl

tin

om

us

Ea

ng

ap

ic

s,

pi

VD

op

Sh

ob

bi

es

rts

&

,r

in

el

OCCUPATIONAL LIVES OF HEALTHY OLDER PEOPLE

29 ties (61%), socialising (57%), hobbies, sports and religious activities (44%) and reading (37%). Very few of the participants regarded any activities as solely personal. Activities were also categorised as combinations of all these. Paid work was regarded as necessary and enjoyable by 27% of the participants who did this activity, as was voluntary work (21%) and caring for both adults (20%) and children (15%). Personal care (16%) was regarded as necessary and personal, and socialising (21%) and hobbies, sports and religious activities (18%) were regarded as personal and enjoyable. Few of the participants regarded activities as personal, enjoyable and necessary. At least 10% of the participants had mixed categorisation for each activity. Indeed, 75% of the participants categorised eating and drinking in a mixed manner, whereas 72% of those who did domestic activities had mixed categorisation. Personal care (47%) and caring for adults (40%) were also categorised by many in a mixed fashion (Table 4).

100 90 80

tion). Of all, 23 (25%) participants cared for others. Over half of the participants engaged in hobbies, sport and religious activities (50, 56%) and reading (58, 64%), whereas 65 (72%) spent time in social activities. The mean number of minutes spent in each activity, where n indicates those who actually participated in the activity, is presented in Figure 2. The importance of this type of analysis was noticeable for activities where there were fewer participants (McKenna et al., 2007). For example, those who actually participated in paid work spent a mean of 279 minutes (19%, range = 120450 minutes, SD = 128). Similarly, those doing voluntary work spent 171 minutes (12%, range = 30390, SD = 98) and those caring for children spent 132 minutes (9%, range = 30 300, SD = 89).

Categorisation of activity

Over half of the day (886 minutes, 62% of the day, range = 1501440, SD = 263) was spent in necessary activities, and nearly half in enjoyable activities (676 minutes, 47%, range = 2701290, SD = 240). Personal activities took a fth of the day (282 minutes, 20%, range = 01320, SD = 281; Fig. 3). However, with the minutes spent asleep removed, the participants spent only a third (494 minutes, 34%, range = 601020, SD = 207) of the day in necessary activities, whereas 604 minutes (42%, range = 2101050, SD = 165) were spent in enjoyable activities and only 196 minutes (16%, range = 0870, SD = 196) in personal activities. (These percentages do not equate to 100% as each activity can be assigned more than one category; e.g. work could be regarded as enjoyable and necessary.) Activities most commonly classied as necessary were shopping and appointments (47%), paid work (45%) and sleep (42%; Table 2). Activities most frequently classied as enjoyable were watching television and related activi-

Including sleep Excluding sleep

Percentage of day

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Necessary

Enjoyable

Personal

FIGURE 3: The percentage of the day spent in necessary, enjoyable and personal activities.

450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0

Mean Mean of those who participated in that activity

FIGURE 2: Comparing mean number of minutes spent in an activity by all participants with mean number of minutes spent by those who actually participated in the activity.

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation

ep & es TV re st , m tic a n ct us = iv ic 90 iti , es co Ea m n tin pu = g 85 te an rs d n dr = in 85 ki ng n H = So ob Pe 90 ci bi rs a es l on n ,s Sh al = po 65 ca op rts re pi ,r ng n el = ,a ig 89 pp io n oi n nt = m 50 en ts R n Pa ea = 53 id di ng w or n k Tr = an 58 av d el ed n u Vo = ca 47 lu tio nt n C a n ar ry = in w 11 g or fo k rc n C = hi ar ld 19 in re g n fo n ra = du 13 lts n = 10 om

Sl e

Minutes

Activity

30

R. CHILVERS ET AL.

TABLE 4: Number and percentage of those participating in each activity, who classied the activity as necessary, enjoyable or personal or a combination of any of the three Necessary and enjoyable (%) 11 (12) 3 (27) 4 2 2 8 (21) (20) (15) (15) Necessary and personal (%) 14 (16) Enjoyable and personal (%) 9 (18) 8 (14) 12 (18) Necessary, enjoyable and personal (%) 2 (11)

n Sleep and rest Personal care Eating and drinking Domestic activities Hobbies, sports and religion Paid work and education Voluntary work Caring for adults Caring for children Shopping appointments TV, radio, music and computers Reading Socialising Travelling 90 88 90 85 50 11 19 10 13 53 85 58 65 47

Necessary (%) 42 (47) 17 (19) 13 (15) 5 (45) 2 3 3 25 (11) (30) (23) (47)

Enjoyable (%) 22 (44) 3 (16) 4 (31) 52 (61) 24 (41) 33 (51) 6 (13)

Personal (%)

Mixed (%) 33 41 65 64 6 (37) (47) (72) (75) (12)

3 (27) 7 4 3 7 21 (37) (40) (23) (13) (25)

10 (21)

6 (13)

7 (12) 18 (28) 16 (34)

To aid interpretation, only results over 10% have been reported.

Discussion

Demographic data

Participants who were selected using the sampling method were a statistically fair demographic reection of the UK population aged 5085 years with two exceptions; a disproportionately high number of women (65, 68%), compared with national statistics (54%), and the participants rating their overall health more positively than the general population for their age group, which is to be expected from the inclusion criteria (Soule et al., 2005).

Time use

The time-use data reveal that, similar to previous studies, these UK participants spent most time sleeping (mean 490 minutes), although less than that found in the ONS (2005) survey for those aged over 65 years (580 minutes), in the whole population (537 minutes; ONS) or in the Fricke and Unsworth (2001) and Stanley (1995) studies (530 and 522 minutes, respectively). The participants in this study also appeared to spend considerably less time in passive leisure activities than that found in other studies (154 minutes). The ONS (2005) survey recorded this as the second most time-consuming activity for those aged over 65 years, reporting spending 79 minutes more per day in this activity, as also found in Fricke and Unsworths (2001) and Stanleys (1995) studies (217 and 288 minutes, respectively).

Indeed, this group spent less time watching television and related activities than the general population across all age ranges (168 minutes; ONS). The amount of time spent in all the remaining activities was greater for this group than for those aged over 65 years in the ONS survey, with the exception of reading and travel. Both Stanley (1995) and Fricke and Unsworth (2001) reported that their participants experienced health problems, whereas the ONS (2005) surveyed a random sample of the population, which suggests that these discrepancies in time use could be as a result of this groups positive health status, supporting the assertion that health and occupations are linked (Law et al., 1998). Although a causal relationship cannot be established, the data suggest that this group of healthy older people spent more time in physically active, social and productive activities that have been identied as important by older people (Legarth, Ryan & Avlund, 2005), and associated with successful ageing and increased quality of life (Depp & Jeste, 2006; Rowe & Kahn, 1997). The gender bias towards women may also be a factor in the differences noted; however, this bias was also apparent in other studies (Fricke & Unsworth, 2001; McKenna et al., 2007; Stanley, 1995). Differences in time use between genders largely conform to traditional Western socio-cultural role expectations (McKinnon, 1991), although many of these differences would fall under the broad category of domestic activities in this study.

Journal compilation

C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists

OCCUPATIONAL LIVES OF HEALTHY OLDER PEOPLE

31 ings suggest that these participants are not passive or withdrawn, as proposed by the disengagement theory (Cumming & Henry, 1961), but are leading full and active occupational lives and contributing to society, as suggested by Hugman (1999) and Havighurst (1961).

It is to be expected that compared with the general population across all age ranges (ONS, 2005), this group spent considerably less time in paid work or in caring for children, because of their lifestage. Less time was also spent in travel, which was in common with the national statistics for this age group, possibly because much of the younger populations travelling is related to employment (ONS). This is comparable with McKenna et al.s (2007) results that engagement in paid work and transport was signicantly related to age, with older groups less likely to engage in these activities. More time was spent in habitual, routine activities (Kielhofner, 2008) such as domestic activities, eating and drinking, personal care and shopping, which, compared with the whole population, suggests that this group has adopted the slower pace of life identied by Jonsson et al. (2000). However, the older population spent more time in hobbies, sports and religious activities, reading and voluntary work, compared with the younger population (ONS). These older people may have fewer obligations and external demands than at other lifestages, and their resulting increase in discretionary time may enable them to take part in more intrinsically motivated leisure activities (Jonsson et al.). They may also be meeting their needs for physical and social activities, providing themselves with a sense of productivity, or meeting their belonging, esteem and cognitive needs, all of which have been identied as important in successful ageing (Depp & Jeste, 2006; Legarth et al., 2005). Finally, these participants may be using these activities to provide structure and routine to their time (Jonsson et al.; Kielhofner). By meeting such needs through activities, these older people may be contributing to their health and wellbeing (Clark et al., 1997; Wilcock, 1998).

Categorisation data

Much of the literature claims that a balance of activities is required for health and wellbeing (Backman, 2004). It was found that necessary activities dominated (886 minutes, 62%) the study; however, once sleep (494 minutes, 34%) was removed, enjoyable activities were most prevalent (604 minutes, 42%), and only 16% (196 minutes) of the day was found to be spent in personal activities. This differs from Turners (1997; cited in Turner, 2002) ndings. Majority of this group of older people were beyond the age of retirement, and therefore were unlikely to be participating in paid work, which contributes signicantly to younger peoples productive time use. They were also likely to have greater amounts of discretionary time (Jonsson et al., 2000) with which to do enjoyable, rather than necessary, activities. Another explanation may be that the words necessary, enjoyable and personal were not interpreted with the same meaning as productive, leisure and self-care as used in the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CAOT, 2002). For example, eight participants did not report any personal activities whatsoever, whereas a signicant number of people regarded sleep as necessary, yet it seems unlikely that sleep would be regarded as productive (CAOT). The same was found to be true for eating and drinking, which generally would not be viewed as productive (CAOT). The exception was the term enjoyable, which did seem to correspond to leisure activities. Caring for children was reported by many as enjoyable, although for others it was also necessary, suggesting that this activity carried obligations and responsibilities, above and beyond enjoyment in a grandparenting role. Finally, the people in this group may have found placing their activities into a one-word, concrete category difcult, limiting and articial. There was no scope to express that engagement in an activity may merely have been to pass the time or for its social element rather than from any intrinsic motivation (Legarth et al., 2005). These difculties are similar to those expressed by Fricke and Unsworth (2001) and Stanley (1995), when asking whether an activity was liked or valued. Problems in interpreting the categorisation are highlighted by the many activities categorised as mixed. In this study, although many activities were broadly grouped together, each separate activity may have had a different meaning and motivation to the individual. Within domestic activities for example, an individual may regard laundry as personal, vacuuming as necessary and baking as enjoyable, hence mixed domestic activities. Activities repeated throughout the day also frequently had a mixed categorisation. Sleeping was often

Activities most commonly participated in

It is not surprising that all participants spent some time sleeping, eating and drinking, to meet their basic needs. Similarly, a large majority spent some time in personal care and domestic activities; again these are routine and habitual daily activities that are widely regarded as selfcare occupations (CAOT, 2002; Kielhofner, 2008). Twothirds of the group took part in social activities, and half in hobbies, sports or religious activities. Engagement in activities is an important factor in successful ageing, which suggests that this groups occupational lives are contributing positively towards their experience of ageing, health and wellbeing (Clark, 1997; Wilcock, 1998). Although the participants spent less time watching television, listening to the radio or using computers than those in the ONS, 2005 survey, 94% did participate in these activities at some point, which suggests that it remains a popular activity. Paid work, voluntary work and caring activities were participated in by some of the participants (11, 21 and 25%, respectively). The benets of productive occupations, such as volunteering, include providing structure, meeting esteem and social needs and contributing to occupational balance and wellbeing. These nd C

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation

32 reported as necessary from midnight until dawn, but necessary and enjoyable when going to bed, suggesting perhaps that sleep was regarded as a necessity, but the activity of going to bed was also pleasurable. Alternatively, the high number of mixed activities could again indicate the difculty experienced in encapsulating the meaning of an activity in just one word. Time-use data collection is not without its limitations (Harvey et al., 1999). In this study, data were collected in half-hour slots; therefore, if more than one activity was undertaken per half-hour slot, it was not always recorded. Conversely, activities that took less than half an hour may have been under-reported. Additionally on occasion, an outward journey was recorded, but not the return, suggesting that there were gaps in what was noted. The participants recorded just one day of the week; therefore, less frequently occurring activities such as clubs, volunteering or religious activities were missed (Harvey & Pentland, 1999). The convenience sampling of a UK population reduces the transferability of these ndings. However, it has provided additional insights into the routines and occupations of older people. Trustworthiness of the ndings could be improved in further studies, by using a combination of methodologies (Farnworth, 2004) such as interviews, which would give a greater insight into the reasons for and meaning of engaging in occupations. It is acknowledged that the use of the words necessary, enjoyable and personal needs further investigation, including examining their concurrent validity with the performance areas of productivity, leisure and self-care (Kielhofner, 2006).

R. CHILVERS ET AL.

gest that time-use diaries could be valuable tools to establish the range of activities that an individual engages in and the meanings associated with these activities. From this, a greater insight into an individuals occupational performance could be achieved, in particular in the areas of habituation and occupational balance (CAOT, 2002; Kielhofner, 2008).

Conclusion

This study found that older UK residents who considered themselves to be healthy spent less time in sleep, rest and passive activities than the general population across all age ranges, and more time in work, shopping, hobbies, caring and social activities than those of the same age. This is in accordance with the principle underpinning occupational therapy that health and occupations are linked (Clark, 1997; Wilcock, 1998). The active, productive and social activities with which these older people lled their time may also contribute positively to their experience of ageing (Depp & Jeste, 2006; Rowe & Kahn, 1997). This group appears to have adopted a slower pace of life as noted by Jonsson et al. (2000), compared with the whole adult population, but nonetheless was found to lead full and active occupational lives and contribute to society. In addition, once time spent in sleep was discounted, the group was found to spend more time in enjoyable activities, followed by necessary and then personal activities. The fact that this group regarded themselves as healthy suggests that this balance of activities is not detrimental to their health (Backman, 2004). However, further research would be required to establish if this balance was directly contributing to their good health status. There is some evidence that these older people may have found it difcult to express why they were doing an activity in just one of three pre-coded words, whose meaning could be interpreted differently from the customary occupational therapy terms self-care, leisure and productivity. This research found that older people are a diverse group of individuals who are meeting their needs with dynamic, positive activities. This highlights the importance of a client-centred approach to occupational therapy, which enables clients to have choice, control and diversity in their activities when meeting their needs. Similar studies with different groups of older people, such as those who specically did not consider themselves as healthy or those aged over 85 years, would also be of interest, for comparison with this group (McKenna, Liddle, Brown, Lee & Gustafsson, 2009).

Implications for occupational therapy practice

This study suggests that occupational therapists working with older people should not regard them as one homogenous client group but should consider each as an individual, with their own unique occupational performance (CAOT, 2002; Kielhofner, 2008). The ndings regarding the range of time spent in various activities indicate a diverse group of individuals who are meeting their needs in dynamic, positive activities. The participants who consider themselves to be healthy are spending less time in passive activities than the general population across all age ranges and approximately half of their waking day in enjoyable activities. Occupational therapists need to ensure that their clients are enabled to engage in active and enjoyable activities also. This highlights the importance of holistic and client-centred practice, ensuring that clients have choice, control and diversity in their activities when meeting their needs. The meaning associated with activities, and the distribution of time spent in necessary, personal and enjoyable activities also need to be considered for occupational performance, health and wellbeing to be optimised. Time-use data collection is not routine in occupational therapy practice; however, the ndings of this study sug-

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1997). Time use survey, Australia: A users guide. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Journal compilation

C 2010 The Authors 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists

OCCUPATIONAL LIVES OF HEALTHY OLDER PEOPLE

33

Legarth, K., Ryan, S. & Avlund, K. (2005). The most important activity and the reasons for that experience reported by a Danish population at age 75 years. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68 (11), 501508. McKenna, K., Broome, K. & Liddle, J. (2007). What older people do: Time use and exploring the link between role participation and life satisfaction in people aged 65 years and over. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54 (4), 273284. McKenna, K., Liddle, J., Brown, A., Lee, K. & Gustafsson, L. (2009). Comparison of time use, role participation and life satisfaction of older people after stroke with a sample without stroke. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56 (3), 177188. McKinnon, A. (1991). Occupational performance of activities of daily living among elderly Canadians in the community. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58 (2), 6066. Meyer, A. (1922). The philosophy of occupational therapy. Archives of Occupational Therapy, 1 (1), 110. Ofce for National Statistics. (2005). Time spent on main activity by age group with rates of participation. 2005. Great Britain. [Online]. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http:// www.statistics.gov.uk/StatBase/expodata/spreadsheets/ D9497.xls Robinson, J. (1999). The time diary method. In: A. Pentland, W. Harvey, M. Lawton & M. McColl (Eds.), Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 4790). New York: Kluwer Academic. Rowe, J. & Kahn, R. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37 (4), 433440. Rudman, D., Cook, J. & Polatajko, H. (1996). Understanding the potential of occupation: A qualitative exploration of seniors perspectives on activity. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51 (8), 640650. Soule, A., Babb, P., Evandrou, M., Balchin, S. & Zealey, L. (2005). Focus on older people. Ofce for National Statistics [Online] Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http://www. statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_compendia/foop05/ Olderpeople2005.pdf. SPSS. (1998). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows Version 11.5. USA: SPSS Inc. Stanley, M. (1995). An investigation between engagement in valued occupations and life satisfaction for elderly South Australians. Journal of Occupational Science: Australia, 2 (3), 100114. Turner, A. (1997). Do current activity media used within occupational therapy education reect the changing activity patterns of living today? Paper presented to the College of Occupational Therapists Annual Conference, Southampton. Cited in Turner, A. (2002) Occupation for therapy. In: A. Turner, M. Foster & S. Johnson (Eds.), Occupational therapy and physical dysfunction (5th ed., pp. 2546). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Wilcock, A. (1998). Occupation for health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61 (8), 340345. World Health Organization. (2002) Active ageing: A policy framework. [Online]. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http:// whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf

Backman, C. (2004). Occupational balance: Exploring the relationships among daily occupations and their inuence on wellbeing. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71 (4), 202209. Ball, V., Corr, S., Knight, J. & Lowis, M. (2007). An investigation into the leisure occupations of older adults. British Journal of Occupational Therapy., 69(1), 1522. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2002). Enabling occupation: An occupational theory perspective (2nd ed.). Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE. Clark, F. et al. (1997). Occupational therapy for independentliving older adults. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278 (16), 13211326. Creek, J. (2004). Occupational therapy dened as a complex intervention. London: COT. [Online]. Retrieved 1 March 2007, from http://www.cot.co.uk/MainWebSite/ Resources/Document/OTDened.pdf. Cumming, E. & Henry, W. (1961). Growing old. New York: Basic Books. Depp, C. & Jeste, D. (2006). Denitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14 (1), 620. Eurostat. (2008). Harmonised European time use surveys. [Online]. Retrieved 18 September 2009, from http:// epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-RA08-014/EN/KS-RA-08-014-EN.PDF Farnworth, L. (2004). Time use and disability. In: M. Molineux (Ed.), Occupation for occupational therapists (pp. 4665). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Fricke, J. & Unsworth, C. (2001). Time use and importance of instrumental activities of daily living. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48, 118131. Harvey, A. & Pentland, W. (1999). Time use research. In: A. Pentland, W. Harvey, M. Lawton & M. McColl (Eds.), Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 318). New York: Kluwer Academic. Havighurst, R. (1961). Successful ageing. Gerontologist, 1, 813. Hugman, R. (1999). Ageing, occupation and social engagement: Towards a lively later life. Journal of Occupational Science, 6 (2), 17. Jonsson, H., Borell, L. & Sadlo, G. (2000). Retirement: An occupational transition with consequences for temporality, balance and meaning of occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 7 (1), 2937. Kielhofner, G. (1977). Temporal adaptation: A conceptual framework for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31 (4), 235242. Kielhofner, G. (2006). Research in occupational therapy: Methods of inquiry for enhancing practice. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Kielhofner, G. (Ed.). (2008). Model of human occupation. (4th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Knight, J., Ball, V., Corr, S., Turner, A., & Lowis, M. (2007). An empirical study to identify older adults engagement in productive occuaptions. Journal of Occupational Science, 14 (3), 145153. Law, M., Steinwender, S. & Leclair, L. (1998). Occupation, health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65 (2), 8191.

2010 The Authors C 2010 Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Journal compilation

Copyright of Australian Occupational Therapy Journal is the property of Blackwell Publishing Limited and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

También podría gustarte

- 43 - Bejerholm & Eklund OTMHDocumento21 páginas43 - Bejerholm & Eklund OTMHRoxana BadicioiuAún no hay calificaciones

- SdarticleDocumento13 páginasSdarticleBere CanelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Balance Balancing and HealthDocumento22 páginasBalance Balancing and HealthPhilip ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- Motives To Practice Exercise in Old Age and Successful Aging - A Latent Class AnalysisDocumento7 páginasMotives To Practice Exercise in Old Age and Successful Aging - A Latent Class AnalysisBryan NguyenAún no hay calificaciones

- Older People Home AloneDocumento9 páginasOlder People Home AloneRainAún no hay calificaciones

- Outdoor Recreation For Every Body An Examination of Constraints ToDocumento6 páginasOutdoor Recreation For Every Body An Examination of Constraints Toperakang00Aún no hay calificaciones

- Bahan Bacaan - 1 - Culture The Missing Link in Health ReseaDocumento10 páginasBahan Bacaan - 1 - Culture The Missing Link in Health ReseaannisyahmerianaazanAún no hay calificaciones

- Paradigm of The StudyDocumento6 páginasParadigm of The Studyjervrgbp15Aún no hay calificaciones

- Art LiftDocumento9 páginasArt LiftJannie BalistaAún no hay calificaciones

- Health Promot. Int. 2009 Rana 36 45Documento10 páginasHealth Promot. Int. 2009 Rana 36 45Riny BudiartyAún no hay calificaciones

- Motivations For Participation in Physical Activity Across The LifespanDocumento16 páginasMotivations For Participation in Physical Activity Across The LifespanPaopao MacalaladAún no hay calificaciones

- Exploring Risk Factors For Depression Among Older Men Residing in MacauDocumento11 páginasExploring Risk Factors For Depression Among Older Men Residing in MacauaryaAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding Perceptions of Successful Aging in ZimbabweDocumento14 páginasUnderstanding Perceptions of Successful Aging in ZimbabweInnocent T SumburetaAún no hay calificaciones

- Psychosocial Dimensions of Exceptional Longevity: A Qualitative Exploration of Centenarians' Experiences, Personality, and Life StrategiesDocumento18 páginasPsychosocial Dimensions of Exceptional Longevity: A Qualitative Exploration of Centenarians' Experiences, Personality, and Life StrategiesSamyjane AlvarezAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Ni AteDocumento61 páginasResearch Ni Ate11 ICT-2 ESPADA JR., NOEL A.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Taking up activity in later life benefits healthy agingDocumento6 páginasTaking up activity in later life benefits healthy agingmartinAún no hay calificaciones

- Health Promoting Behaviors Turkish Workers Nurses' ResponsibilitiesDocumento9 páginasHealth Promoting Behaviors Turkish Workers Nurses' Responsibilitiesmanali_thakarAún no hay calificaciones

- Estudio de Horas de Sueño en EnfermerasDocumento9 páginasEstudio de Horas de Sueño en EnfermerasEliane Esquivel RuizAún no hay calificaciones

- Flexible Work Schedules and Mental and Physical Health. A Study of A Working Population With Non-Traditional Workinh Hours PDFDocumento13 páginasFlexible Work Schedules and Mental and Physical Health. A Study of A Working Population With Non-Traditional Workinh Hours PDFDavid T.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Session Slides 2 - Understanding - HealthDocumento22 páginasSession Slides 2 - Understanding - HealthOsman Abdul-MuminAún no hay calificaciones

- Conflict Between Women's Physically Active and Passive Leisure Pursuits The Role of Self-Determination and Influences On Well-Being.Documento23 páginasConflict Between Women's Physically Active and Passive Leisure Pursuits The Role of Self-Determination and Influences On Well-Being.Luisa GomezAún no hay calificaciones

- AloneDocumento8 páginasAloneOsiris Mark CaducoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Wellness Beliefs Scale PostPrintDocumento32 páginasWellness Beliefs Scale PostPrintSophia YangAún no hay calificaciones

- OverviewDocumento15 páginasOverviewreemaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lecture 1 - Health and Health PromotionDocumento46 páginasLecture 1 - Health and Health Promotionkris_fishAún no hay calificaciones

- Cockerham and ColleaguesDocumento14 páginasCockerham and ColleaguesMubarak AbdullahiAún no hay calificaciones

- Conceptualizing and Measuring HealthDocumento28 páginasConceptualizing and Measuring HealthAhmed AfzalAún no hay calificaciones

- Therapeutic Effects of GardeningDocumento10 páginasTherapeutic Effects of GardeningRaoni SousaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and PhysiciansDocumento18 páginasThe Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and Physiciansmutiara yerivandaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and PhysiciansDocumento18 páginasThe Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and Physiciansmutiara yerivandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Autopercepción MortalidadDocumento10 páginasAutopercepción MortalidadEduardo JohannesAún no hay calificaciones

- Bedah Iskandar Japardi33Documento13 páginasBedah Iskandar Japardi33Norvita AsniAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Jetlag: Misalignment of Biological and Social Time: Chronobiology InternationalDocumento14 páginasSocial Jetlag: Misalignment of Biological and Social Time: Chronobiology InternationalTâÿÿàbá ĮkrâmAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Proposal, Lifestyle, With Edit Points, Edited 1Documento46 páginasResearch Proposal, Lifestyle, With Edit Points, Edited 1Boon AimanAún no hay calificaciones

- Activity TheoryDocumento6 páginasActivity TheoryJohn Louie EscardaAún no hay calificaciones

- 1999 Anyas PDFDocumento3 páginas1999 Anyas PDFfissionmailedAún no hay calificaciones

- Effects of Exercise on Quality of Life for Chronic Disease PatientsDocumento18 páginasEffects of Exercise on Quality of Life for Chronic Disease PatientsMario LanzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Out (1) NurcesDocumento19 páginasOut (1) Nurcesjosselyn ayalaAún no hay calificaciones

- Article CritiqueDocumento9 páginasArticle CritiqueKhyzra NaveedAún no hay calificaciones

- Using Occupations to Improve Quality of Life for Alzheimer's PatientsDocumento8 páginasUsing Occupations to Improve Quality of Life for Alzheimer's Patientsmuhammad taufikAún no hay calificaciones

- Holding On: Background and SignificanceDocumento9 páginasHolding On: Background and Significanceleafar78Aún no hay calificaciones

- Can I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesDocumento16 páginasCan I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesjcpaterninaAún no hay calificaciones

- Subjective well-being overview benefits health relationships workDocumento16 páginasSubjective well-being overview benefits health relationships workInten Dwi Puspa DewiAún no hay calificaciones

- Occupational Therapy and Older People Powerpoint Elle Updated 6-5-10Documento13 páginasOccupational Therapy and Older People Powerpoint Elle Updated 6-5-10Raluca AndreeaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sample Paper 1Documento10 páginasSample Paper 1Arman EspejoAún no hay calificaciones

- QALYs DALYs and HALYs A Unifying Framework For The 2023 Journal of HealtDocumento12 páginasQALYs DALYs and HALYs A Unifying Framework For The 2023 Journal of Healt94tzgzzj9hAún no hay calificaciones

- Iwh Briefing Shift Work 2010Documento8 páginasIwh Briefing Shift Work 2010AbiDwiSeptiantoAún no hay calificaciones

- 5 18 BannaiDocumento15 páginas5 18 BannaiALOPEZAún no hay calificaciones

- Spiritual Well-Being and Lifestyle Choices in Adolescents: A Quantitative Study Among Afrikaans-Speaking Learners in The North West Province of South AfricaDocumento11 páginasSpiritual Well-Being and Lifestyle Choices in Adolescents: A Quantitative Study Among Afrikaans-Speaking Learners in The North West Province of South Africahendra pranataAún no hay calificaciones

- Ijbt 1 - 3 - 3 - 423-433Documento11 páginasIjbt 1 - 3 - 3 - 423-433Shamerra SabtuAún no hay calificaciones

- Are Recessions Good for Your Health? When Ruhm Meets GHHDocumento44 páginasAre Recessions Good for Your Health? When Ruhm Meets GHHanahh ramakAún no hay calificaciones

- Can I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesDocumento16 páginasCan I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesEmi MedinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Does Tai Chi/Qi Gong Help Patients With Multiple Sclerosis?: N. Mills, J. Allen, S. Carey MorganDocumento10 páginasDoes Tai Chi/Qi Gong Help Patients With Multiple Sclerosis?: N. Mills, J. Allen, S. Carey MorganZoli ZolikaAún no hay calificaciones

- Spiritual Care in General Practice Rushing in or F PDFDocumento17 páginasSpiritual Care in General Practice Rushing in or F PDFGiulia de GaetanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ali Marsh, Leigh Smith, Jan Piek Curtin University of Technology, Australia Bill Saunders Graylands Hospital, AustraliaDocumento13 páginasAli Marsh, Leigh Smith, Jan Piek Curtin University of Technology, Australia Bill Saunders Graylands Hospital, Australiamanu volmerAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effects of Qigong On Reducing Stress and Anxiety and Enhancing Body Mind Well BeingDocumento10 páginasThe Effects of Qigong On Reducing Stress and Anxiety and Enhancing Body Mind Well BeingSamo JaAún no hay calificaciones

- Employees Feel Happier and More Active From Recalling Work's Positive EventsDocumento17 páginasEmployees Feel Happier and More Active From Recalling Work's Positive EventsÍcaro AngeloAún no hay calificaciones

- 2018 A Systematic Review of The Relationship Between Physical Activity and HappinessDocumento18 páginas2018 A Systematic Review of The Relationship Between Physical Activity and HappinessFrancisco Antonó Castro Weith100% (1)

- Flourishing: Health, Disease, and Bioethics in Theological PerspectiveDe EverandFlourishing: Health, Disease, and Bioethics in Theological PerspectiveAún no hay calificaciones

- Gmail - MatlabDocumento2 páginasGmail - MatlabAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- GT Design Surge Line DataDocumento3 páginasGT Design Surge Line DataAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Analytical SolnDocumento1 páginaAnalytical SolnAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- ReadmeDocumento3 páginasReadmeAnushiMaheshwariAún no hay calificaciones

- Measuring 2004 1Documento5 páginasMeasuring 2004 1Aditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Heat Exchangers: Effectiveness-NTU Method Chapter SectionsDocumento15 páginasHeat Exchangers: Effectiveness-NTU Method Chapter SectionsrajindoAún no hay calificaciones

- Notes On Matlab ProgrammingDocumento11 páginasNotes On Matlab ProgrammingAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- RP SP Far PDFDocumento11 páginasRP SP Far PDFAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Installation, Licensing, and Activation Installation GuideDocumento182 páginasInstallation, Licensing, and Activation Installation GuideDenisAún no hay calificaciones

- 20 12 2013 02 40 34 Thermal BinderDocumento26 páginas20 12 2013 02 40 34 Thermal BinderAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- CMake ListsDocumento1 páginaCMake ListsAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Statistical Analysis 2: Pearson Correlation: Research Question Type: What Kind of Variables? Common ApplicationsDocumento4 páginasStatistical Analysis 2: Pearson Correlation: Research Question Type: What Kind of Variables? Common ApplicationsAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Foreign Exchange MarketDocumento37 páginasForeign Exchange MarketAkanksha MittalAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 2: Heat Exchangers Rules of Thumb For Chemical Engineers, 5th Edition by Stephen HallDocumento85 páginasChapter 2: Heat Exchangers Rules of Thumb For Chemical Engineers, 5th Edition by Stephen HallNadirah RahmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Kailash YatriksDocumento3 páginasKailash YatriksAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Student Details ListDocumento30 páginasStudent Details ListAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Lectures 3 and 5 On RTTDocumento26 páginasLectures 3 and 5 On RTTAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Notesonhydraulic00owenrich DjvuDocumento1415 páginasNotesonhydraulic00owenrich DjvuAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Revised Digital PresenterDocumento4 páginasRevised Digital PresenterjugheadurAún no hay calificaciones

- Coating BaZrO3Documento7 páginasCoating BaZrO3Aditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Log FileDocumento2 páginasLog FileAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- 6 Unit 2 - Metal Forming ProcessesDocumento27 páginas6 Unit 2 - Metal Forming ProcessesAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- 3 Unit 2 - Arc, Gas, Plastic Welding, LBW, EBW and Thermit WeldingDocumento96 páginas3 Unit 2 - Arc, Gas, Plastic Welding, LBW, EBW and Thermit WeldingAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- MEC230 Unit 2 Solid State Welding ProcessesDocumento33 páginasMEC230 Unit 2 Solid State Welding ProcessesAditya Kumar100% (2)

- 5 Unit 2 - Welding Quality and DefectsDocumento31 páginas5 Unit 2 - Welding Quality and DefectsAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Unit 2 - Metal Joining ProcessDocumento37 páginas1 Unit 2 - Metal Joining ProcessAditya Kumar100% (3)

- Entry Parameters of R Ocket NozzleDocumento8 páginasEntry Parameters of R Ocket NozzleAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- 2 Unit 2 - Brazing, Soldering and Adhesive BondingDocumento13 páginas2 Unit 2 - Brazing, Soldering and Adhesive BondingAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- 8 Simulation 2perbladDocumento11 páginas8 Simulation 2perbladAditya KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Genetics - 2023 - Saura - Spanish Mental Health Residents Perspectives About Residency Education On The GeneticsDocumento8 páginasClinical Genetics - 2023 - Saura - Spanish Mental Health Residents Perspectives About Residency Education On The GeneticsJuanAún no hay calificaciones

- Braam Et Al-2016-The Cochrane Library PDFDocumento75 páginasBraam Et Al-2016-The Cochrane Library PDFFelipe AlecrimAún no hay calificaciones

- MonographDocumento48 páginasMonographShella AmiriAún no hay calificaciones

- O.Ph.D.-4-2020 MKBUDocumento2 páginasO.Ph.D.-4-2020 MKBURaj KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Component 3 - Flood Risk Technical Report - Final Draft by GA and PAGASADocumento98 páginasComponent 3 - Flood Risk Technical Report - Final Draft by GA and PAGASAAllexby C. EstardoAún no hay calificaciones

- ASsignement No.2 in Risk ManagementDocumento6 páginasASsignement No.2 in Risk ManagementEdgard Laurenz Montellano GeronimoAún no hay calificaciones

- Retail Service Quality at Kannan Department StoresDocumento5 páginasRetail Service Quality at Kannan Department StoresvidhyathiyagarajanAún no hay calificaciones

- Module 3 Principles of High Quality AssessmentDocumento9 páginasModule 3 Principles of High Quality AssessmentRycel JucoAún no hay calificaciones

- Concept PaperDocumento4 páginasConcept Paperjanet a. silosAún no hay calificaciones

- NURS800 Myra Levine Conservation Model-1Documento12 páginasNURS800 Myra Levine Conservation Model-1risqi wahyu100% (1)

- Understanding Audiences Through Reception AnalysisDocumento7 páginasUnderstanding Audiences Through Reception AnalysisLia KurniawatiAún no hay calificaciones

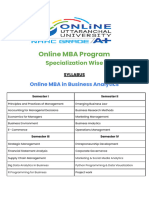

- Uu Online Mba SyllabusDocumento3 páginasUu Online Mba SyllabusVimalesh YadavAún no hay calificaciones

- Regression analysis of factors affecting car salesDocumento5 páginasRegression analysis of factors affecting car salesSS 1818Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sinking City (9-23-05)Documento4 páginasSinking City (9-23-05)venice20Aún no hay calificaciones

- Use Gartner's Business Value Model To Make Better Investment DecisionsDocumento15 páginasUse Gartner's Business Value Model To Make Better Investment Decisionsdavid_zapata_41Aún no hay calificaciones

- Decision Support For Water Resource Management: An Application Example of The MULINO DSSDocumento6 páginasDecision Support For Water Resource Management: An Application Example of The MULINO DSSSudharsananPRSAún no hay calificaciones

- Evolution of Organizational DevelopmentDocumento18 páginasEvolution of Organizational DevelopmentsuhithbadamiAún no hay calificaciones

- Pagadian City Disaster Risk Reduction Plan - A New Relief Operation Management SystemDocumento20 páginasPagadian City Disaster Risk Reduction Plan - A New Relief Operation Management SystemAmber GreenAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of E-Service Quality Towards Repurchasing Intention: Mediated by Customer Perceived Value and SatisfactionDocumento102 páginasThe Impact of E-Service Quality Towards Repurchasing Intention: Mediated by Customer Perceived Value and SatisfactionTeuku Muhammad Iqbal AnwarAún no hay calificaciones

- Transorganisational ChangeDocumento26 páginasTransorganisational ChangeAshutosh ShuklaAún no hay calificaciones

- Wong 2000Documento115 páginasWong 2000Alexandre Maceno de LimaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cooper, Mick (2011) - Meeting The Demand For Evidence Based Practice. Therapy Today 22Documento9 páginasCooper, Mick (2011) - Meeting The Demand For Evidence Based Practice. Therapy Today 22Arina IulianaAún no hay calificaciones

- Blooms Taxonomy Teacher Planning KitDocumento1 páginaBlooms Taxonomy Teacher Planning Kitapi-222746680Aún no hay calificaciones

- Yoga Kaivalyadham ModuleDocumento71 páginasYoga Kaivalyadham Modulearunsrl100% (1)

- "Technical Skills Upgrade": 4 ASCENT TrainingDocumento4 páginas"Technical Skills Upgrade": 4 ASCENT Trainingsantiago67Aún no hay calificaciones

- Risk Management in PT. Maja Ruang Delapan PDFDocumento43 páginasRisk Management in PT. Maja Ruang Delapan PDFDea BonitaAún no hay calificaciones

- Good Governance, Local Government, Accountability and Service Delivery in TanzaniaDocumento21 páginasGood Governance, Local Government, Accountability and Service Delivery in TanzaniadidierAún no hay calificaciones

- A Study On Effectiveness of Internet AdDocumento17 páginasA Study On Effectiveness of Internet AdSiddhi kumariAún no hay calificaciones

- "One Day I Want To Own A Football Club in Italy", Rinita Singh, CEO, Quantum Market ResearchDocumento2 páginas"One Day I Want To Own A Football Club in Italy", Rinita Singh, CEO, Quantum Market ResearchSangitaa AdvaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Process Improvement in Furniture Manufacturing: A Case StudyDocumento6 páginasProcess Improvement in Furniture Manufacturing: A Case StudyamaroAún no hay calificaciones