Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Unified Schools - Shun Clayton

Cargado por

greattrekTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Unified Schools - Shun Clayton

Cargado por

greattrekCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Unified nation

Following the recent General Election, Malaysia faces calls for more unity amongst its citizens as the races become more and more polarised. I believe one of the reasons for this polarisation is because of our education system which divides our citizens into schools according to race. While this may not be part of our education policy, in reality parents perceive that the best chances for their children is to be educated in their mother tongue. This is a misnomer since the Chinese speak several different dialects while Chinese schools teach in Mandarin which the majority of Chinese dont speak at home and the Tamil schools cater only to Tamils and not to the other Indian ethnicities of Malaysia.

Parties on both sides of the political divide have historically been opposed to unifying our education system so that all public school students go to just one type of school. This feeling stems from before independence when the British introduced Tamil schools for the Indian labour force, who mainly worked in the plantations sector, and Chinese schools for the Chinese who were imported as manual labour. Other schools used English as a medium of instruction with a few, mainly at primary level, using Malay. In 1970, the government began to introduce Malay as the language of instruction in all national schools although the Chinese and Tamil schools were allowed to keep operating as before so long as they offered Malay, a mandatory subject for all schools, and kept to the National Curriculum.

This has led to national schools being populated mostly by Malays while the Chinese and Indians have shunned national schools in favour of schools which offer an education in their own language. A Centre for Public Policy Studies report in February 2012 indicates that one reason for this is that the Chinese and Indians view national schools as providing an inferior education. Another is the perception that national schools are becoming more and more Islamicised.

Now that the electorate has voted against race-based politics with the routing of the Malaysian Indian Congress and the Malaysian Chinese Association (both components of the ruling coalition) and, by inference, racial policies, it is time for us to go forward as one united nation rather than a conglomeration of different races, each interested only in advancing their particular culture. We should start at unifying our school system. When children play and learn together, they do not see the differences. My cousins daughter, who recently graduated high school, says that her multicultural education provided her with the means to understand and respect different cultures. As she enters university, she says that this understanding will help her to find a job in our ever-shrinking globalised world.

University of Washingtons Dr James A Banks, a respected leader in multicultural education, in an interview last year with NEA (National Education Association) Today suggested that a multicultural education was essential to foster citizen participation in a democratic society. When people dont participate, when people dont know each other, this just further polarizes. True, he was speaking about education in the US, however, I believe the same holds true wherever you are in the world. Humanity is universal and is not restricted to one race or one nation.

One problem with implementing a unified schooling system is that most teachers have not been taught how multiculturism should be advanced. A 2008 study by Universiti Sains Malaysia student, Najeemah Mohd Yusuf, indicated that the majority of teachers in national schools (who are mostly Malay) do not know how to implement multicultural practices into their curriculum since they have not been taught what multiculturism is nor how it should be contained in their teaching materials.

And how do you go about dismantling a system that most parents think is best for their child? Not to mention that the two largest minority races feel that their rights would be impinged upon if the government were to abolish mother tongue education.

In a conversation I had with a friend who went to a Chinese school, she tells me that she doesnt feel the Chinese system works for most children. Yes, they learn discipline and learn early on the mechanics of science and maths. However, she says that the system of rote learning they use does not promote critical thinking. When it was time to enter secondary education, her parents sent her to a convent school which taught in English. She says that she found it particularly difficult switching to another language and that the Chinese school didnt prepare her for the real world in which people come from all cultures and backgrounds. She admits that she had very few friends of other races at primary school and wishes that it wasnt so.

A widely held perception is that school leavers of Chinese and Tamil schools lack the English skills necessary to find a good job. This is also true of graduates of national schools but vernacular school graduates cannot speak Bahasa (Malay) with any competence and that means that employment opportunities are very limited for this group of students. (I do not include Chinese private schools in this category which do quite a good job of preparing their students for adult life.) While I could not obtain hard statistics on the fate of our vernacular school graduates, anecdotal evidence suggests that a sizeable proportion of them end up either in menial jobs or in gangs. According to a dissertation, Racial Inequality and Affirmative Action in Malaysia and South Africa, written in 2010 by Lee Hwok-Aun of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the rate of unemployment among Chinese and Indian secondary school leavers rose between 1995 and 2004 whereas unemployment rates among bumiputeras (mainly Malay and some indigenous tribes) fell from 6% to 4.8% in the same period. Those who do well have usually transferred to other schools at secondary level, as my friend did, and thus have had to mingle with those of other races.

There are many parents, and other concerned parties, who argue that going to a unified school means that one has to give up ones culture and identity. Dong Jiao Zong, the guardians of Chinese education, says that sending children to national schools will erode their identity as Chinese and that it is imperative that Chinese students keep their cultural roots. While I agree that it is necessary to know ones roots, I would also argue that they are doing a great disservice to the Chinese community by making sure they are segregated from the mainstream the Malays who make up the majority in Malaysia.

With political will, it can be made possible to attend classes in a unified school in Malay and/or English with other languages and cultures offered as electives. It is also possible to repeal the law which stops schools from offering religious knowledge as a subject. What would it mean for our children if they could learn each others religions and cultures and understand the

significance of certain rituals and taboos? Would that not make us more tolerant of each other?

There are many rocks on the way towards a unified education system. The government will have to address issues of poor quality teaching, the perceived Islamification of national schools and the attitudes of the parents themselves; and they will have to ensure that teachers in national schools are culturally sensitive. It will not be easy but, at the end of the day, do we want to see our children embroiled in bitter race disturbances because they did not grow up together and do not understand each other?

También podría gustarte

- QuestionnaireDocumento2 páginasQuestionnairegreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

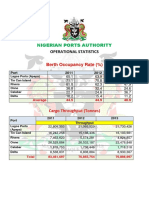

- Nigerian Ports Authority: Operational StatisticsDocumento3 páginasNigerian Ports Authority: Operational StatisticsgreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Ogundana's ModelDocumento3 páginasOgundana's ModelgreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Modes of TransportDocumento7 páginasAdvantages and Disadvantages of Different Modes of TransportgreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Quoting and ParaphrasingDocumento2 páginasQuoting and ParaphrasinggreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 3, Question 10: This Time Period Is Irrelevant!Documento1 páginaAssignment 3, Question 10: This Time Period Is Irrelevant!greattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Criticalmanagement-Week One Study QuestionsDocumento1 páginaCriticalmanagement-Week One Study QuestionsgreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- One Planet Worth Keeping Zeer ParryDocumento2 páginasOne Planet Worth Keeping Zeer ParrygreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- NASA Finds Message From God On MarsDocumento1 páginaNASA Finds Message From God On MarsgreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Dime Is in A Name - Mwadimeh Wa'keshoDocumento3 páginasWhat The Dime Is in A Name - Mwadimeh Wa'keshogreattrek100% (1)

- Lagos - Ibadan Expressway: FG Had To Intervene - JonathanDocumento2 páginasLagos - Ibadan Expressway: FG Had To Intervene - JonathangreattrekAún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Demo Lesson Plan in Hebrew LitDocumento2 páginasDemo Lesson Plan in Hebrew LitJunilyn SamoyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Academic WordsDocumento124 páginasAcademic WordsЖамиля КушчубаеваAún no hay calificaciones

- Week 25 DLLDocumento6 páginasWeek 25 DLLVivian BaltisotoAún no hay calificaciones

- Academic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureDocumento15 páginasAcademic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureGio SalupanAún no hay calificaciones

- Diachronic StudentsDocumento17 páginasDiachronic StudentsPréé TtyyAún no hay calificaciones

- Narrative Matters - DR Grant BageDocumento188 páginasNarrative Matters - DR Grant BagecouscousnowAún no hay calificaciones

- PTI Education PolicyDocumento48 páginasPTI Education PolicyPTI Official95% (21)

- An Analysis of Job Market Expectations of Students of Economics-A Case Study On Stamford University BangladeshDocumento2 páginasAn Analysis of Job Market Expectations of Students of Economics-A Case Study On Stamford University BangladeshAzharul IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Ashley Aldrich Resume 2016Documento3 páginasAshley Aldrich Resume 2016api-257330283Aún no hay calificaciones

- 1.1 Background and ConceptsDocumento19 páginas1.1 Background and ConceptsMuzzammil Hanif MyminiAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis Fia Eka Safitriiii PDFDocumento44 páginasThesis Fia Eka Safitriiii PDFFIA EKA SAFITRIAún no hay calificaciones

- Elements of A ProfessionDocumento15 páginasElements of A ProfessionDarlene Dacanay DavidAún no hay calificaciones

- ELTM Chapter 6 (Teaching Across Age Levels)Documento5 páginasELTM Chapter 6 (Teaching Across Age Levels)DikaAún no hay calificaciones

- Personal Development: Quarter 1 - Module 12: Ways To Improve Brain FunctionsDocumento20 páginasPersonal Development: Quarter 1 - Module 12: Ways To Improve Brain FunctionsIzanagi Nomura67% (6)

- Tubog Proposed LP For INSET 2023 - 2024Documento15 páginasTubog Proposed LP For INSET 2023 - 2024MARILYN ANTONIO ONGKIKOAún no hay calificaciones

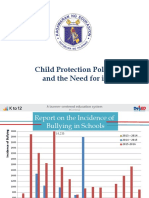

- Module 3. Session 2. Activity 1. Child Protection and The Need For ItDocumento64 páginasModule 3. Session 2. Activity 1. Child Protection and The Need For ItSamKris Guerrero MalasagaAún no hay calificaciones

- PDET - Session 3 - Providing Warmth and StructureDocumento48 páginasPDET - Session 3 - Providing Warmth and StructureEmma Ducante100% (1)

- What Is Test? How Many Types of Test Are There?discuss The Qualities of A Good Test. Discuss The Difference Between Test and AssessmentDocumento6 páginasWhat Is Test? How Many Types of Test Are There?discuss The Qualities of A Good Test. Discuss The Difference Between Test and AssessmentKhan Zahidul Islam RubelAún no hay calificaciones

- Discuss Obd DLP UbdDocumento1 páginaDiscuss Obd DLP UbdAdie ZasAún no hay calificaciones

- Edre 4860 005 Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 páginasEdre 4860 005 Annotated Bibliographyapi-384686513Aún no hay calificaciones

- New Legacy ELC Lead TeacherDocumento3 páginasNew Legacy ELC Lead Teacheryunie poohAún no hay calificaciones

- Legal Bases of Philippine Educational SysteDocumento7 páginasLegal Bases of Philippine Educational SysteJose Pedro DayandanteAún no hay calificaciones

- Arellano University - A. Bonifacio Campus The Problem and Its BackgroundDocumento24 páginasArellano University - A. Bonifacio Campus The Problem and Its BackgroundDee Jay de JesusAún no hay calificaciones

- Resume May6 2021Documento4 páginasResume May6 2021api-547652458Aún no hay calificaciones

- Unit 4 Lesson Planning Module 1 Classroom Management: All The Students All The TimeDocumento2 páginasUnit 4 Lesson Planning Module 1 Classroom Management: All The Students All The TimeMary Ann D. Gaboy50% (2)

- English-7 - SLM - Q1 - M1 - V1.0-CC-released-18Oct.2020Documento16 páginasEnglish-7 - SLM - Q1 - M1 - V1.0-CC-released-18Oct.2020Shine GlamAún no hay calificaciones

- History and Philosophy of Movement EducationDocumento6 páginasHistory and Philosophy of Movement EducationJewel Marie BayateAún no hay calificaciones

- 44th College Day Report 2021/2022Documento63 páginas44th College Day Report 2021/2022Sesilia Esti Asmira (TJC)50% (2)

- What Is The Purpose of EducationDocumento3 páginasWhat Is The Purpose of EducationPerla MartinezAún no hay calificaciones

- Fbs Weekly DLL 2022Documento6 páginasFbs Weekly DLL 2022Fatima DatukakaAún no hay calificaciones