Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The King James Bible

Cargado por

ihabDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The King James Bible

Cargado por

ihabCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1

DARKNESS INTO LIGHT: An address to mark the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible Professor David Frost, Principal, the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies, Cambridge

_______________________________________________________ [St Johns Gospel 3. 16-21, in the King James Version

16

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved. He that believeth on him is not condemned: but he that believeth not is condemned already, because he hath not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God. And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. For every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved. But he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God.]

17

18

19

20

21

_________________________________________________________________

My text is six verses from the Gospel you have just heard, the gospel according to St John, chapter 3, verses 16 to 21. It is, however, in a translation two hundred and twenty-seven years earlier than the King James Version whose 400th anniversary we celebrate today that of John Wycliffe, translating into the English of 1384: 16 For God louede so the world, that he yaf his `oon bigetun sone, that ech man that bileueth in him perische not, but haue euerlastynge lijf. 17 For God sente not his sone in to the world, that he iuge the world, but that the world be saued bi him. 18 He that bileueth in hym, is not demed; but he that bileueth not, is now demed, for he bileueth not in the name of the `oon bigetun sone of God. 19 And this is the dom, for liyt cam in to the world, and men loueden more derknessis than liyt; for her werkes weren yuele. 20 For ech man that doith yuele, hatith the liyt; and he cometh not to the liyt, that hise werkis be not repreued. 21 But he that doith treuthe, cometh to the liyt, that hise werkis be schewid, that thei ben don in God.

What is clear is that this version wont do for a modern audience, whether in 1611 or today. But what is also clear is that in words and structure this is very much what we are used to in a traditional translation of the Bible. For the four hundredth anniversary of the so-called Authorized Version, we have had a veritable outpouring on television, radio and in the press: some of it illuminating as to the processes of the forty-seven translators in six committees that worked on the King James translation, two committees each in Oxford, Cambridge and Westminster. But we have also had paeans of praise, straight from Silly-Boys Hall, for that same version as being, with the contemporary plays of William Shakespeare, a twin-cornerstone of some fundamental British decency of character that developed over the next four hundred years an inheritance from a highpoint of English culture that we are in danger of neglecting at our peril. (Indeed, we have been told on British television that the heritage was so twinned that Shakespeare was vastly influenced by the King James Bible and this despite all his major plays being written before the publication of the new version in 1611.) Shakespeare was indeed much influenced by the Bible but in the Geneva version done by Protestant exiles in 1560, about fifty years before the King James translation. It was the most popular version in Shakespeares day and for forty-four years after his death, till the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. It is true that the humanity and insights of Shakespeare have greatly affected human relations, not just in Britain but world-wide. But so has the gospel of Christ and the Old and New Testaments of the Bible and that influence has little to do with whatever translation was used. If the old translators sought striking expression, that was because they had first been struck by their Hebrew and Greek originals. And in the case of the Bible, it has been the sense not the expression, the message not the medium, that mattered. To use the anniversary of the King James Bible to drag back our youth for their good to an archaic English version on the ground of its supposedly unique quality is to betray the principles of translation that made that version excellent and which might serve as a model for our own work. First, the King James translators knew that the time must come inevitably when changes in the language would give any translation a false quaintness and a dangerous obscurity. Re-translation was a necessity. Seventy-one years earlier, Thomas Cranmer in his preface to the second edition of the Great Bible [1540] had observed that re-translation into current English was the ancient custom of the Church: For it is not much above one hundred years ago, since scripture hath not been accustomed to be read in the vulgar tongue within this realm. And many hundred years before that, it was translated and read in the Saxons' tongue, which at that time was our mother tongue, whereof there remain yet divers copies found lately in old abbeys, of such 3

antique manner of writing and speaking, that few men now be able to read and understand them. And when this language waxed old and out of common usage, because folk should not lack the fruit of reading, it was again translated into the newer language, whereof yet also many copies remain and be daily found. But secondly, the King James translators understood (as we do not) that novelty, originality, individualism are a dangerous temptation. Not for them the folly of the New English Bible and the Jerusalem Bible in the last century of trying to make all things new, expressing ancient truth in our own idiom, and deliberately avoiding the wording of older versions. The old translators would have been astonished. Why alter what had been put in such memorable form by a predecessor? Why not steal what was good? Except that notions of ownership didnt come much into the heads of seventeenth century translators. So it is that Wycliffes Bible doesnt seem much different to versions centuries later. The translators of the King James Bible were under royal instruction not to attempt anything new but to revise the Bishops Bible of 1568, published forty-three years earlier. As they summed up their brief in their Preface of the Translators to the Reader, they never thought from the beginning that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one . . . but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one . . . Hence, in the King James version of the six verses of my text, all 144 words are identical to those of the Bishops Bible, forty-three years earlier, with one word (howe) omitted as redundant, euyll doeth reversed to doeth evil, and yt his deedes may be knowen turned to the rather more po nderous that his deeds may be made manifest, after the example of the Geneva Bible of 1560 (which generally offers the King James translators a more elevated diction). Where Wycliffe (1395) and Coverdale (1535) had talked of good deeds being done in God, from Tyndale (1534), the Matthew Bible (1537), the Great Bible (1539 and 1540), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Bishops Bible (1568), right through to the King James Version of 1611, it was generally felt more fitting that your good deeds should be wrought in God. If we look back seventy-seven years from the King James Version to the Tyndale New Testament (which was the first version in almost modern English), out of the 144 words of the King James version 122 words are exactly as Tyndale wrote them, in the same place, in the same word-order and in the same grammatical and syntactical structure with all that means for borrowed effects of sound, rhythm and balance. To put it mildly no one strove for novelty. Forty-seven no doubt cantankerous scholars subjected their egos to the task of producing the best possible version, keeping in touch with their Hebrew and Greek originals, surveying the great and by now extensive tradition of past translation, all diligently compared with earlier English versions (as their title-page attested). They then had their decisions re-considered by their peers and finally overseen by the Great Committee that from January 1609 for two years went 4

through all that the six smaller committees had done. It was a work of corporate genius, of the Church militant together with the Church in glory, if it was a work of genius at all. But that is not our idea of how genius works. The solitary individual, unappreciated in his lonely garret, is the one we think capable of great art. That, however, is not how the Holy Spirit works. In the first Sunday after Pentecost, it is well to remember that the Spirit came in a rushing wind and tongues of fire to a committee of the Apostles. The Jerusalem Council when deciding what to do about the Gentiles hit on what seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us and that was in a committee. The great ecumenical Councils of the Church that defined the essence of Christian faith were grand committees. But those committees saw the Church as entrusted with the faith once delivered to the saints, and themselves as the guardians of a tradition. If we want the scriptures once again to strike the British consciousness with the sword of the Spirit, we must learn from the corporate humility of the makers of the King James Bible, who in their translation appreciated and stole from the past, but tailored it to fit a present and a future need. May the six committees and the forty-seven translators of the King James Version be reverenced for what they did. As the Orthodox would put it, May their memory be eternal, in the keeping of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

También podría gustarte

- 3 - The Hampton Court ConferenceDocumento8 páginas3 - The Hampton Court Conferenceds1112225198Aún no hay calificaciones

- King James Bible 1611Documento1457 páginasKing James Bible 1611Mark CourtmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Zechariah 9Documento7 páginasZechariah 9Maxi Zeravika100% (1)

- The Subject of The Origins of MankindDocumento2 páginasThe Subject of The Origins of MankindBernard CoxAún no hay calificaciones

- The Book of Moses and The Magicians OtheDocumento5 páginasThe Book of Moses and The Magicians OtheАртём ДруидAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Did Noah Curse Canaan The Son of Ham ?Documento5 páginasWhy Did Noah Curse Canaan The Son of Ham ?Errol SmytheAún no hay calificaciones

- Real World - Johnson CompressedDocumento95 páginasReal World - Johnson CompressedPaul Raines100% (1)

- Hebrew Calendar PDFDocumento4 páginasHebrew Calendar PDFLuis100% (1)

- Outline of The Holy Bible Hebrew Bible Genesis: Based On The English Standard Version (ESV)Documento2 páginasOutline of The Holy Bible Hebrew Bible Genesis: Based On The English Standard Version (ESV)Roh Mih100% (1)

- Yisraelite Basic PreceptsDocumento53 páginasYisraelite Basic Preceptsapi-329036268100% (1)

- The Day of The LordDocumento7 páginasThe Day of The Lordapi-3711938Aún no hay calificaciones

- World Chronology From A Perspective of Biblical ChristianityDocumento239 páginasWorld Chronology From A Perspective of Biblical ChristianitycemarsoAún no hay calificaciones

- 9 1 1... Emergency... Red Alert... Headline!!!Documento6 páginas9 1 1... Emergency... Red Alert... Headline!!!BesorahSeed0% (1)

- The Progressive Torah: Level One ~ Genesis: Color EditionDe EverandThe Progressive Torah: Level One ~ Genesis: Color EditionAún no hay calificaciones

- Girdlestone - Synomyns of The OTDocumento462 páginasGirdlestone - Synomyns of The OTds1112225198Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Whole Counsel of GodDocumento107 páginasThe Whole Counsel of GodNkor Ioka100% (1)

- Passover MeditationsDocumento60 páginasPassover MeditationsKingdom WitnessAún no hay calificaciones

- CaedmonDocumento9 páginasCaedmonyonseienglishAún no hay calificaciones

- Forty Years in The WildernessDocumento12 páginasForty Years in The Wildernesstwttv003Aún no hay calificaciones

- 02 2520 Year ProphecyDocumento181 páginas02 2520 Year ProphecyDeon Conway100% (1)

- 2 Thessalonians 1Documento2 páginas2 Thessalonians 1Crystal SamplesAún no hay calificaciones

- SBL 1976 QTR 2Documento60 páginasSBL 1976 QTR 2Brian S. Marks100% (1)

- The Bible and The Counting of Time-Part 2: Ptolemy's CanonDocumento3 páginasThe Bible and The Counting of Time-Part 2: Ptolemy's CanonfrankiriaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Holy Bible New Testament Complete in Telegu (Telugu) India PDFDocumento562 páginasThe Holy Bible New Testament Complete in Telegu (Telugu) India PDFIndia Bibles100% (2)

- 10 Beautiful Descriptions of Heaven From The Bible - Bible StudyDocumento13 páginas10 Beautiful Descriptions of Heaven From The Bible - Bible StudyRobbieD455Aún no hay calificaciones

- Melchizedek (Part 1a)Documento13 páginasMelchizedek (Part 1a)sogunmolaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter Thirty-Six: Message Quick Reference GuideDocumento7 páginasChapter Thirty-Six: Message Quick Reference GuideAyeah GodloveAún no hay calificaciones

- Barack Hussein Obama Is The Antichrist! America Is The Fourth Kingdom of Daniel!Documento15 páginasBarack Hussein Obama Is The Antichrist! America Is The Fourth Kingdom of Daniel!MarkLBAún no hay calificaciones

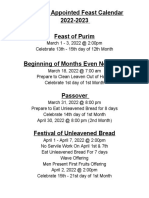

- 2022-2023 Appointed Feast Day CalendarDocumento8 páginas2022-2023 Appointed Feast Day CalendarSonofManAún no hay calificaciones

- Steps To ChristDocumento128 páginasSteps To ChristtsupkoAún no hay calificaciones

- Law or Grace? Louis K. Dickson 1937Documento44 páginasLaw or Grace? Louis K. Dickson 1937Ryan O'Neil 船 SeatonAún no hay calificaciones

- KJV Vs NivDocumento5 páginasKJV Vs Nivapi-274978290Aún no hay calificaciones

- 357 Errors of The Modernist's Critical TextDocumento131 páginas357 Errors of The Modernist's Critical TextJesus LivesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Seven HeadsDocumento12 páginasThe Seven HeadsJamal Telbert PinderAún no hay calificaciones

- God's Golden GloryDocumento6 páginasGod's Golden GlorySteve-OAún no hay calificaciones

- Creation and The Bible: An Exegesis of GenesisDocumento61 páginasCreation and The Bible: An Exegesis of GenesisRudolfSiantoAún no hay calificaciones

- Family Bible Fragment PDFDocumento74 páginasFamily Bible Fragment PDFOficyna Wydawnicza VOCATIOAún no hay calificaciones

- See All Things Made NewDocumento5 páginasSee All Things Made NewBesorahSeedAún no hay calificaciones

- The Sayings Gospel Q The Text of QDocumento17 páginasThe Sayings Gospel Q The Text of QtraperchaperAún no hay calificaciones

- Shabbath Home Study Guide English WebDocumento34 páginasShabbath Home Study Guide English WebDemetria ClarkeAún no hay calificaciones

- Throne Room of GodDocumento11 páginasThrone Room of Godapi-292011099Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Islamic Beast, False Prophet and Anti-ChristDocumento19 páginasThe Islamic Beast, False Prophet and Anti-ChristJack BrownAún no hay calificaciones

- The Book of Acts Study Guide UpdateDocumento36 páginasThe Book of Acts Study Guide UpdateCBI creating Best InformationAún no hay calificaciones

- Papal Rome's Rise and Fall ForetoldDocumento59 páginasPapal Rome's Rise and Fall ForetoldNuno VenâncioAún no hay calificaciones

- Glorified Body: Quotes From The Collection of Messages Preached by Rev. William Marrion Branham, Since 1947Documento40 páginasGlorified Body: Quotes From The Collection of Messages Preached by Rev. William Marrion Branham, Since 1947Freddy JoséAún no hay calificaciones

- 04 The Truth About Angels Study 4Documento5 páginas04 The Truth About Angels Study 4High Mountain StudioAún no hay calificaciones

- The Holy Bible King James VersionDocumento742 páginasThe Holy Bible King James VersionSubhajit Saha100% (1)

- Dominion of The Creation Calendar: The Sabbath or ShabbatDocumento8 páginasDominion of The Creation Calendar: The Sabbath or ShabbatSonofMan100% (1)

- God'S Promised: Dr. Chuck MisslerDocumento50 páginasGod'S Promised: Dr. Chuck MisslerCris D PutnamAún no hay calificaciones

- The Canopy EffectDocumento4 páginasThe Canopy Effectacts2and380% (1)

- Epv Kings of Israel 1Documento30 páginasEpv Kings of Israel 1PS86Aún no hay calificaciones

- Preface 2nd Edition, Rev 1Documento11 páginasPreface 2nd Edition, Rev 1Patricio Piedra100% (1)

- ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS Com Englishmagazines 176 PDFDocumento68 páginasARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS Com Englishmagazines 176 PDFmacAún no hay calificaciones

- English Spanish Czech Bible - The Gospels III - Matthew, Mark, Luke & John: King James 1611 - Reina Valera 1909 - Bible Kralická 1613De EverandEnglish Spanish Czech Bible - The Gospels III - Matthew, Mark, Luke & John: King James 1611 - Reina Valera 1909 - Bible Kralická 1613Aún no hay calificaciones

- English Spanish Bible - The Gospels V - Matthew, Mark, Luke & John: King James 1611 - Youngs Literal 1898 - Reina Valera 1909De EverandEnglish Spanish Bible - The Gospels V - Matthew, Mark, Luke & John: King James 1611 - Youngs Literal 1898 - Reina Valera 1909Aún no hay calificaciones

- Issue 005.pdf Pharaohs MagDocumento8 páginasIssue 005.pdf Pharaohs MagihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Issue 003.pdf Pharahos CaricatureDocumento8 páginasIssue 003.pdf Pharahos CaricatureihabAún no hay calificaciones

- AbydosDocumento11 páginasAbydosihab100% (1)

- Effective Time Management E BookDocumento10 páginasEffective Time Management E BookMalik MirzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Issue 008.pdf CaricatureDocumento8 páginasIssue 008.pdf CaricatureihabAún no hay calificaciones

- 1994 Fall - Vol15.#3Documento19 páginas1994 Fall - Vol15.#3ihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Egyptian Furniture and Musical Instruments C L RDocumento9 páginasEgyptian Furniture and Musical Instruments C L RihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Woman Heart FeelingDocumento27 páginasWoman Heart FeelingihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Batteries Other Than Dry Cell BatteriesDocumento19 páginasBatteries Other Than Dry Cell BatteriesihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Coptic Alphabetic ConceptsDocumento5 páginasCoptic Alphabetic ConceptsihabAún no hay calificaciones

- GPON: The Standard For PON Deployment and Service Evolution: OSI Confidential InformationDocumento23 páginasGPON: The Standard For PON Deployment and Service Evolution: OSI Confidential Informationchaidar_lakareAún no hay calificaciones

- The Iconic Story of JesusDocumento1 páginaThe Iconic Story of JesusihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Journal Articles - From IACS List - lm.2008Documento12 páginasJournal Articles - From IACS List - lm.2008ihabAún no hay calificaciones

- Chem 2 Organic ChemistryDocumento5 páginasChem 2 Organic ChemistryihabAún no hay calificaciones

- TradtionDocumento62 páginasTradtionihabAún no hay calificaciones

- RipDocumento4 páginasRipPavan KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Statements of The Salaf On The Knowledge of Imam Abu HanifahDocumento2 páginasStatements of The Salaf On The Knowledge of Imam Abu HanifahtakwaniaAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Old English Literature Caedmon's Hymn: OE Text & TranslationDocumento2 páginas1 Old English Literature Caedmon's Hymn: OE Text & TranslationFlorentina DrobotaAún no hay calificaciones

- Dragon's Dogma Quest Guide Part 5 (Deep TroubleDocumento4 páginasDragon's Dogma Quest Guide Part 5 (Deep TroubleAnanyo ChattopadhyayAún no hay calificaciones

- Frascari M The Tell The Tale Detail 3 ADocumento14 páginasFrascari M The Tell The Tale Detail 3 AinkognitaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Portrait of A Lady - (Notes)Documento3 páginasThe Portrait of A Lady - (Notes)Balvinder Kaur67% (3)

- Introduction To Poetry - Whitla, 176-185Documento11 páginasIntroduction To Poetry - Whitla, 176-185Andrea Hernaiz RuizAún no hay calificaciones

- Edgar Poe's "The Black CatDocumento8 páginasEdgar Poe's "The Black CatNuruddin Abdul Aziz100% (1)

- H.H. Richardsons Two Hanged Women. Our Own True Selves andDocumento14 páginasH.H. Richardsons Two Hanged Women. Our Own True Selves andCarlos HenriqueAún no hay calificaciones

- Conrad Williams - The UnblemishedDocumento359 páginasConrad Williams - The UnblemisheddaipuAún no hay calificaciones

- Voice and Speech in The Theatre PDFDocumento176 páginasVoice and Speech in The Theatre PDFJoannaTmsz100% (4)

- Unit 9 Meet My Family Yr1Documento3 páginasUnit 9 Meet My Family Yr1RamonaUsopAún no hay calificaciones

- Garipzanov2005 HISTORICAL RE-COLLECTIONS - REWRITING THE WORLD CHRONICLE IN BEDE'S DE TEMPORUM RATIONE PDFDocumento17 páginasGaripzanov2005 HISTORICAL RE-COLLECTIONS - REWRITING THE WORLD CHRONICLE IN BEDE'S DE TEMPORUM RATIONE PDFVenerabilis BedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Part 6 - PG 88-106Documento2 páginasPart 6 - PG 88-106api-232728249Aún no hay calificaciones

- Theater in Mindanao - ExcerptDocumento5 páginasTheater in Mindanao - ExcerptJane Limsan PaglinawanAún no hay calificaciones

- Explorers Handbook PDFDocumento2 páginasExplorers Handbook PDFClark0% (3)

- Writers Effect EssayDocumento3 páginasWriters Effect Essayapi-341757363Aún no hay calificaciones

- Amba NeelayatakshiDocumento4 páginasAmba NeelayatakshiAswith R ShenoyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies Information For AuthorsDocumento3 páginasThe Journal of Cave and Karst Studies Information For AuthorsAlexidosAún no hay calificaciones

- Om Gum Shrim Mantra GuideDocumento2 páginasOm Gum Shrim Mantra Guidevector7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Various Posts CollectedDocumento38 páginasVarious Posts Collectednightclown100% (1)

- Gita Mahatmya - PDF - Bhagavad Gita - KrishnaDocumento3 páginasGita Mahatmya - PDF - Bhagavad Gita - KrishnaSwathi MaiyaAún no hay calificaciones

- LoveDocumento30 páginasLoveGeorich NarcisoAún no hay calificaciones

- Alice Falls Down the Rabbit HoleDocumento3 páginasAlice Falls Down the Rabbit HoleCamelia SerbanAún no hay calificaciones

- The RomancersDocumento7 páginasThe RomancersKristin RichinsAún no hay calificaciones

- Review Oswalt, John N,. The Book of Isaiah Chapters 40-66 (NICOT)Documento2 páginasReview Oswalt, John N,. The Book of Isaiah Chapters 40-66 (NICOT)gersand68520% (1)

- Lesson 4 Multimedia FormatsDocumento17 páginasLesson 4 Multimedia FormatsSarah naomi BelarminosantosAún no hay calificaciones

- ESMQ DR Renny Mclean Session 4 RecapDocumento4 páginasESMQ DR Renny Mclean Session 4 Recapfrancofiles100% (1)

- Ragtime NovelDocumento106 páginasRagtime NovelKesha Alsina100% (2)

- Quarter 3 Week 4 English 6Documento19 páginasQuarter 3 Week 4 English 6Lory AlvaranAún no hay calificaciones

- AugustineDocumento46 páginasAugustineItak Cha100% (1)