Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Go Down Old Hannah 3

Cargado por

Christopher JamesDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Go Down Old Hannah 3

Cargado por

Christopher JamesCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Go Down, Old Hannah; Examined Utilizing Sylvan's Theoretical Motifs: Sociocultural, Physical, Psychological, and Ritual The assignment

calls for an application of the theoretical frameworks that Robin Sylvan describes in Chapter 1, the theoretical framework that undergirds the remaining chapters of Traces of the Spirit. However, it would be remiss of me not to begin by mentioning why I chose this particular song / video and a little background information surrounding its usage in African American history. While slave songs and African American spirituals have been familiar to me for a long time - I took a course in "hymnology" in seminary - I was not familiar with how those same songs evolved into prison songs during the early 1900's. Go Down, Old Hannah was a slave song, primarily sung among field slaves of the deep south on cotton plantations. After emancipation, there was the very real threat that the entire cotton industry would collapse due to the lack of cheap labor. To rectify the situation, a series of laws were passed that made being without work, loitering, or being "mischievous" a crime that demanded state incarceration... as long as the "criminal" was black. Thus, the chain gangs and work farms of the time were actually places of legal slavery. It will come as no surprise that the still-remembered slave songs of only a few years prior were quickly appropriated by the new class of slave: the prison inmate. Go Down, Old Hannah, with it's clear reference to the quiet bitterness of the unjustly imprisoned, the depressed acceptance of the nearness of death, and the steady, trudging pace through uncounted hours and days... is a wonderful (albeit painful) example of what Sylvan calls the "sociocultural level" at which music works. Here are the lyrics, given without the call-andrepeat structure of the video: Go Down, Old Hannah Oh, we call the sun ol' Hannah Blazing on my head Yes, we call the sun ol' Hannah And her hair is flamin' red. Why don't you go down, ol' Hannah Don't you rise no more If you come up in the mornin' Bring judgment sure Well I look at ol' Hannah She was turnin' red Well I look at my partner He was almost dead Said if you get lucky, Or make it on your own Please go down by Julie's Tell her I won't be long

Kept sayin' I was a good man But they drove me down Yes, I was a good man, But they drove me down Well, it look like ev'rything Ev'rything I do Yes, it looks like ev'rything I do is wrong The song is much more than Blacking's "humanly organized sound." It imparts a deep emotional affect, both upon the hearer and the participant, though these occur on very different levels. For the prison inmate, the song is primarily one of community. Its sociocultural level of impact is first one of solidarity, of us-together-against-them and only secondarily of musicality (tone, harmony, pitch, etc). While a modern-day UCF student can listen, commiserate, and marvel at the depths which our country's moral history has plumbed, we aren't experiencing it; the song's very nature is not something that can be fully experienced alone, and perhaps by us, not at all. "Moreover, those melodies, harmonies, or rhythms...may have no effect on someone from another culture...[they only have psychological import] within the learned meaning system of a particular sociocultural context" (28-29). Only a slave-laborer can "experience" Go Down, Old Hannah. For the outsider, listening to the song is observational, not experiential. The physicality of slave and prison music had multiple purposes, none of which Sylvan addresses in his text. The rhythm of the chant was very basic to the task at hand; nearby supervisors were known to be violent with "shirkers." A steady "call-and-response" kept all the prisoners working at a measured pace and therefore held potential aggressive response from an ever-present prison supervisor to a minimum. Some tasks (like chopping down trees or pulling stumps) required concerted effort. Call-and-response songs had a very practical application, similar to when a couple of undergraduates are attempting to roll a police car or get an overstuffed couch to a second floor apartment. "One-two-three-HEAVE!" Sylvan stresses the hypnotic qualities associated with the physical level of music, which leads me to wonder: the accelerando and crescendo in the video recording is interesting. I wonder if Go Down, Old Hannah also had the effect of putting the prison workers in a mild trance like state that would enable the day to go by more quickly as Gilbert Rouget suggests (22). While Sylvan separates the psychological level at which we can understand music from the physical, it is clear that the two are connected, at least in terms of entering "altered states of consciousness" and "musical state of being." Suffice it to say that the steady, driving rhythm of Go Down, Old Hannah, along with the accelerando and crescendo demonstrated by the leader, could easily have moved the prison workers to enter an altered state; rather than creating a "heightened state of being," more than likely served to diminish the workers experience of a horrific situation. On this question, we cannot be sure. Ethnomusicologists at that time were rare (and not studying chain gangs). I am keenly fascinated by the insights provided by Jonathan Z Smith regarding the ritual of music and the notion that "ritual represents the creation of a controlled environment...a means of

performing the way things ought to be in conscious tension to the way things are..."(36). This theory - that the ritual aspects inherent in a group of prisoners singing a slave call-and-response song is an attempt to control the uncontrollable - resonates deeply with me. In this regard, I embrace Sylvan's idea that ritualized music creates in the participant both a virtual time (the prisoners can escape the monotony of the task and "time flys by") and a virtual space (the prisoners are, at least psychologically, not working in a field). Go Down, Old Hannah may not be the best depiction of religiosity expressed in music, but it is certainly a fascinating example of how multiple levels of meaning and interpretation can happen, as Sylvan suggests multiple times in the text, simultaneously. Word Count : 1004

También podría gustarte

- Music and Queered Temporality in Slave Play: Imogen WilsonDocumento19 páginasMusic and Queered Temporality in Slave Play: Imogen WilsonAlex KidmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Listening To Ethnographic Holocaust MusiDocumento26 páginasListening To Ethnographic Holocaust MusinerokAún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Elements in Brave New WorldDocumento15 páginasLiterary Elements in Brave New Worldfakeemailadres6100% (2)

- William Irwin Thompson On StockhausenDocumento2 páginasWilliam Irwin Thompson On StockhausenMathew van den BemdAún no hay calificaciones

- Deep Blues-Human Soundscapes For The Archetypal JourneyDocumento42 páginasDeep Blues-Human Soundscapes For The Archetypal JourneydustydiamondAún no hay calificaciones

- Daniel Barenboim Reith Lectures 2006: in The Beginning Was Sound Lecture 5: The Power of MusicDocumento10 páginasDaniel Barenboim Reith Lectures 2006: in The Beginning Was Sound Lecture 5: The Power of MusicAäron WajnbergAún no hay calificaciones

- Ned Rorem analysis of the Beatles' musical evolution from "barbarism to decadenceDocumento3 páginasNed Rorem analysis of the Beatles' musical evolution from "barbarism to decadenceDoghouse ReillyAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Classic Jazz (from its beginnings to Be-Bop)De EverandHistory of Classic Jazz (from its beginnings to Be-Bop)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Cognitive approach to incongruent film musicDocumento15 páginasCognitive approach to incongruent film musicCaterina PapouliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Michael Ventura Hear That Long Snake MoanDocumento32 páginasMichael Ventura Hear That Long Snake Moanhuman999Aún no hay calificaciones

- 08 - Chapter 3Documento79 páginas08 - Chapter 3Kapil BhattAún no hay calificaciones

- Void and Excess in Music: An Extract from Slavoj Žižek's Upcoming Book on HegelDocumento7 páginasVoid and Excess in Music: An Extract from Slavoj Žižek's Upcoming Book on Hegelanon_375404768Aún no hay calificaciones

- Dissonance and Discordance, Consonance and Concordance: An Analysis of Late 20th Century Music As Endemic of A Violent SocietylDocumento19 páginasDissonance and Discordance, Consonance and Concordance: An Analysis of Late 20th Century Music As Endemic of A Violent SocietylLuis Miguel DelgadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Musical Time: An Intersubjective RelationshipDocumento8 páginasMusical Time: An Intersubjective RelationshipmiaafrAún no hay calificaciones

- Francisco Lopez The Big Blur TheoryDocumento19 páginasFrancisco Lopez The Big Blur TheoryAmon BarthAún no hay calificaciones

- An Interpretation of The Musical Themes in Thomas Manns Magic MoDocumento3 páginasAn Interpretation of The Musical Themes in Thomas Manns Magic MoMeshugeRabbiAún no hay calificaciones

- LovingSchumann BarthesDocumento6 páginasLovingSchumann BarthesWaltVult100% (2)

- ListeningBiennialReader 01-1Documento55 páginasListeningBiennialReader 01-1Elsa OviedoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Power of MusicDocumento5 páginasThe Power of MusicLAURIEJERIEAún no hay calificaciones

- Reaction Paper: John Cage InterviewsDocumento6 páginasReaction Paper: John Cage InterviewsTricia TuanquinAún no hay calificaciones

- Music and SocietyDocumento31 páginasMusic and SocietyRodolpho Abreu AndradeAún no hay calificaciones

- Olga Neuwirth - Texts & PhotosDocumento4 páginasOlga Neuwirth - Texts & PhotosLemon SharkAún no hay calificaciones

- Notes On Music and OperaDocumento10 páginasNotes On Music and OperabagofmostlywaterAún no hay calificaciones

- Performing in The Holocaust From Camp Songs To The Song Plays of Germaine Tillion and Charlotte SalomonDocumento26 páginasPerforming in The Holocaust From Camp Songs To The Song Plays of Germaine Tillion and Charlotte SalomonDaniela Silva100% (1)

- Negro Folk Rhymes: Wise and Otherwise: With a StudyDe EverandNegro Folk Rhymes: Wise and Otherwise: With a StudyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Other Sound 11Documento20 páginasThe Other Sound 11P. Emerson WilliamsAún no hay calificaciones

- Essay #5 (Hard)Documento4 páginasEssay #5 (Hard)Tennis ballAún no hay calificaciones

- Eine Vernachlaessigbare Maenge:: (Works-In-Progress)Documento5 páginasEine Vernachlaessigbare Maenge:: (Works-In-Progress)jfkAún no hay calificaciones

- 02 - 832742 - Letter To MKDocumento7 páginas02 - 832742 - Letter To MKJefferson PereiraAún no hay calificaciones

- Yho - Disco No Disco YesDocumento28 páginasYho - Disco No Disco YesyrheartoutAún no hay calificaciones

- On the Road to Freedom: Tomson Highway's Use of Blues Harmonica in 'Dry Lips Oughta Move to KapuskasingDocumento12 páginasOn the Road to Freedom: Tomson Highway's Use of Blues Harmonica in 'Dry Lips Oughta Move to KapuskasingMielleAún no hay calificaciones

- JAFA Brochure REVISED SinglepageDocumento6 páginasJAFA Brochure REVISED Singlepageberkay ustunAún no hay calificaciones

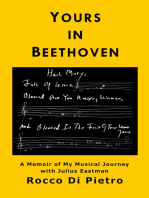

- Yours in Beethoven: A Memoir of My Musical Journey with Julius EastmanDe EverandYours in Beethoven: A Memoir of My Musical Journey with Julius EastmanAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is "Phenomenology of Music" (Celibidache)Documento16 páginasWhat Is "Phenomenology of Music" (Celibidache)Andrew TarkovskyAún no hay calificaciones

- Welcome Address To Freshman at Boston Conservatory Karl PaulnackDocumento6 páginasWelcome Address To Freshman at Boston Conservatory Karl PaulnackMichael StickelmanAún no hay calificaciones

- It's Not A Rave, Officer - Tobias C. Van VeenDocumento11 páginasIt's Not A Rave, Officer - Tobias C. Van Veentobias c. van VeenAún no hay calificaciones

- Il ritorno del dio che balla: Culti e riti del Tarantolismo in ItaliaDe EverandIl ritorno del dio che balla: Culti e riti del Tarantolismo in ItaliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Signifying the Blues Across CulturesDocumento53 páginasSignifying the Blues Across CulturesmidnightAún no hay calificaciones

- JAZZ NOTES: ARMSTRONG, HOLIDAY, AND GUNNDocumento6 páginasJAZZ NOTES: ARMSTRONG, HOLIDAY, AND GUNNBilalAún no hay calificaciones

- Elements of JazzDocumento23 páginasElements of JazzBarbara Manholeti100% (1)

- Some Sadomasochistic Aspects of Musical PleasureDocumento3 páginasSome Sadomasochistic Aspects of Musical PleasureCarlos CuestasAún no hay calificaciones

- Take Me Back:: Ghostface's GhostsDocumento9 páginasTake Me Back:: Ghostface's GhostsPalin WonAún no hay calificaciones

- Downes KierkegaardKissSchumanns 1999Documento14 páginasDownes KierkegaardKissSchumanns 1999kahhkkahhkAún no hay calificaciones

- Sun Ship The Late Recordings of John Col PDFDocumento10 páginasSun Ship The Late Recordings of John Col PDFstzenniAún no hay calificaciones

- Symbolism of Light in Baldwin's 'Sonny's BluesDocumento6 páginasSymbolism of Light in Baldwin's 'Sonny's Bluesteacher_meli0% (1)

- Music and Spirituality: 13 Meditations Around George Crumb's Black AngelsDocumento33 páginasMusic and Spirituality: 13 Meditations Around George Crumb's Black AngelsERHANAún no hay calificaciones

- Sonorous PresenceDocumento21 páginasSonorous PresenceGareth BreenAún no hay calificaciones

- What The Sorcerer Said - Carolyn AbbateDocumento11 páginasWhat The Sorcerer Said - Carolyn AbbatealsebalAún no hay calificaciones

- Adorno - On Jazz PDFDocumento25 páginasAdorno - On Jazz PDFRafael F. CompteAún no hay calificaciones

- Poems Breakdown For SeanDocumento20 páginasPoems Breakdown For Seanzaferismailasvat1786Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hightower - The Musical OctaveDocumento195 páginasHightower - The Musical OctaveFedepantAún no hay calificaciones

- Music As Narrative and Music As Drama: Jerrold LevinsonDocumento14 páginasMusic As Narrative and Music As Drama: Jerrold LevinsonAmila RamovicAún no hay calificaciones

- Harvey SpectralismDocumento4 páginasHarvey SpectralismGuitar ManchesterAún no hay calificaciones

- The Prospects of RecordingDocumento13 páginasThe Prospects of RecordingYasmin Fainstein100% (1)

- Hans Keller: HubermanDocumento15 páginasHans Keller: HubermanAndrew WilderAún no hay calificaciones

- Wild Side 2Documento2 páginasWild Side 2Christopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Traces Analysis 4Documento3 páginasTraces Analysis 4Christopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Hokey Pokey 5Documento3 páginasHokey Pokey 5Christopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- A Music For All Times and PlacesDocumento2 páginasA Music For All Times and PlacesChristopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan of ActionDocumento7 páginasPlan of ActionChristopher James100% (1)

- Drunken Dance 6Documento4 páginasDrunken Dance 6Christopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Wherefore The HeroDocumento9 páginasWherefore The HeroChristopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Ganymede PaperDocumento13 páginasGanymede PaperChristopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Evolutionary EpicDocumento7 páginasEvolutionary EpicChristopher JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- History: The Origin of Kho-KhotheDocumento17 páginasHistory: The Origin of Kho-KhotheIndrani BhattacharyaAún no hay calificaciones

- General First Aid QuizDocumento3 páginasGeneral First Aid QuizLucy KiturAún no hay calificaciones

- What Are Open-Ended Questions?Documento3 páginasWhat Are Open-Ended Questions?Cheonsa CassieAún no hay calificaciones

- Relay Models Per Types Mdp38 EnuDocumento618 páginasRelay Models Per Types Mdp38 Enuazer NadingaAún no hay calificaciones

- Characteristics and Elements of A Business Letter Characteristics of A Business LetterDocumento3 páginasCharacteristics and Elements of A Business Letter Characteristics of A Business LetterPamela Galang100% (1)

- Reading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Documento16 páginasReading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Ericka Marie AlmadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Principle of Utmost Good FaithDocumento7 páginasPrinciple of Utmost Good FaithshreyaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerDocumento33 páginasThe Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerBeto TAún no hay calificaciones

- Climbing KnotsDocumento40 páginasClimbing KnotsIvan Vitez100% (11)

- TOPIC 12 Soaps and DetergentsDocumento14 páginasTOPIC 12 Soaps and DetergentsKaynine Kiko50% (2)

- Writing Assessment and Evaluation Checklist - PeerDocumento1 páginaWriting Assessment and Evaluation Checklist - PeerMarlyn Joy YaconAún no hay calificaciones

- XSI Public Indices Ocean Freight - January 2021Documento7 páginasXSI Public Indices Ocean Freight - January 2021spyros_peiraiasAún no hay calificaciones

- Strategic Planning and Program Budgeting in Romania RecentDocumento6 páginasStrategic Planning and Program Budgeting in Romania RecentCarmina Ioana TomariuAún no hay calificaciones

- NewsletterDocumento1 páginaNewsletterapi-365545958Aún no hay calificaciones

- Special Blood CollectionDocumento99 páginasSpecial Blood CollectionVenomAún no hay calificaciones

- E2415 PDFDocumento4 páginasE2415 PDFdannychacon27Aún no hay calificaciones

- 10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Documento17 páginas10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Aubin DiffoAún no hay calificaciones

- Infinitive Clauses PDFDocumento3 páginasInfinitive Clauses PDFKatia LeliakhAún no hay calificaciones

- Asia Competitiveness ForumDocumento2 páginasAsia Competitiveness ForumRahul MittalAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Growth StagesDocumento3 páginasCritical Growth StagesSunil DhankharAún no hay calificaciones

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishDocumento16 páginasCambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishJonathan ChuAún no hay calificaciones

- NAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureDocumento1 páginaNAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureAnny GSAún no hay calificaciones

- Evolution of The Indian Legal System 2Documento7 páginasEvolution of The Indian Legal System 2Akhil YarramreddyAún no hay calificaciones

- Motorizovaná Pechota RotaDocumento12 páginasMotorizovaná Pechota RotaFran BejaranoAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Use Google FormsDocumento126 páginasHow To Use Google FormsBenedict Bagube100% (1)

- Intermediate Unit 3bDocumento2 páginasIntermediate Unit 3bgallipateroAún no hay calificaciones

- Organizational CultureDocumento76 páginasOrganizational Culturenaty fishAún no hay calificaciones

- USP 11 ArgumentArraysDocumento52 páginasUSP 11 ArgumentArraysKanha NayakAún no hay calificaciones

- Unit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs SimilarDocumento7 páginasUnit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs Similar012 Ni Putu Devi AgustinaAún no hay calificaciones