Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Boeing P-26 Variants PDF

Cargado por

felixoconDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Boeing P-26 Variants PDF

Cargado por

felixoconCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

..

r

Aerofax Minigraph 8

BoeingP.26

Variants

by Peter Bowers

ISBN 094254813-2

1984

Aerofax, Inc.

p.o. Box 120127

Arlington, Texas 76012

ph. 817 261-0689

u.s. Trade Distribution by:

Motorbooks International

729 Prospect Ave.

Osceola, Wisconsin 54020

ph. 715 294-2090

European Trade Distribution by:

Midland Counties Publ1cations

24 The Hollow, Earl Shilton

Leicester, LE9 7NA, England

ph. (0455) 47256

.,; ....--------------

:;

:-

~

Q.

.

Ii:

@

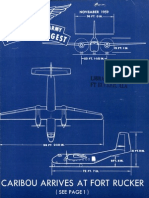

THE BOEING P-26 VARIANTS STORV

Three-quarter front view of the Boeing XP-936 wind tunnel model without propeller. Also missing are the flying wires for the wings and tail surfaces and other

miscellaneous details such as the radio mast and exhaust pipe complex. Model, dated February of 1932, was meticulously built of hardwood with a metal

Townend ring and engine parts.

Wood and fabric full-scale mock-up of XP-936 lacks tail surfaces and landing gear. Noteworthy are the external

wing root mounting of the camera gun, the abbreviated windscreen and headrest, and the use of a rea; engine.

Photo was taken on November 25, 1931.

CREDITS:

The author and Aerofax, Inc. would like to express their

thanks to the following individuals who contributed

photographs andlor data to this Minigraph: Dana Bell,

Jack Binder, Dustin Carter, Robert Cavanagh, Harry

Gann, Walter Jefferies, Fredrick Johnsen, John and Joe

Kobe, Edward LePenske, Edward Maloney, Mike McCary

and Crown Hobbies of Dallas, David Menard, AI Hansen,

James Morrow, Marilyn Phipps of Boeing Historical Ser-

vices, Kenn Rust, Victor Seely, Jay Spenser, Gordon

Swanborough of Air International, Robert Volker, Gordon

Williams, and the late A.U. Schmidt, Eugene Sommerich,

and Joseph Nieto.

PROGRAM HISTORY:

The Boeing P-26, unofficially nicknamed Peashooter

(in the 1930's the term Peashooter was often applied to

single-seat pursuit aircraft; in the context of present-day

historical references, the term is generally considered

to apply specifically to the Boeing P-26), is unique among

US Army pursuit aircraft for at least two reasons: it was

not developed under a standard US Army Air Corps ex-

perimental contract, but rather as a private venture of

the manufacturer with the aid and encouragement of the

Air Corps Materiel Division at Wright Field, Dayton Ohio;

and it broke the established Air Corps tradition of dual

procurement of equivalent models (Curtiss P-6 and Boe-

ing P-12 pursuits; Curtiss 0-1 and Douglas 0-210-38

observation models simultaneously, for example).

While the Curtiss XP-934 (later designated XP-31 by

the US Army Air Corps) was considered the Boeing

XP-936's (P-26 family prototype) primary competition, on-

ly the Boeing pursuit was to see production. This reached

a total of only 136 P-26NBIC airframes. Though appear-

ing small, this order represented the largest single new

pursuit design procurement since 1921. There was,

however, justification for the small production run, as

both the Army and Boeing realized that the new

monoplane was strictly an interim model. In fact, an en-

tirely new generation of high-performance monoplanes,

with more powerful engines and structural and

aerodynamic improvements, was already under

consideration.

In its transitional role, the P-26 was also notable for

being both a last and a first. It was the last Army pursuit

to feature both an open-cockpit and fixed landing gear

with externally-braced wings; and concommiUantly, it

was also America's first production all-metal monoplane

pursuit.

Production P-26's had a US Army service life of eight

and one-half years and eventually became the first US

service aircraft to be passed on to other nations for con-

tinued use. At the time, this was considered extremely

unusual as previous US military aircraft had been scrap-

ped or relegated to training schools following their sevice

careers. It is interesting to note that the last two of the

numerous P-26's relegated to foreign service use were

not retired until 1956. Both aircraft, at the time operated

by the Guatemalan Air Force, were returned to the US.

They are, today, the only known surviving P-26's.

In 1931, when Boeing's historically significant P-12 and

F4B biplane fighter series was still selling well to the US

Army and Navy, respectively, Boeing intuitively foresaw

that the end of the biplane era was near. In fact, the com-

pany had just introduced a revolutionary commercial

monoplane, the Model 200 Monomail, and had already

interested the Army in its Model 214 and 215 twin-engine

bomber derivatives which the Army bought as the Y1 B-9

and YB-9, respectively. Even more significant was the

fact that the company was then designing an equivalent

civil transport, the Model 247, which was soon to revolu-

tionize the air transport industry.

Since the speed of the new B-9 was expected to be

greater than that of contemporary pursuit aircraft, Boe-

ing offered the War Department an opportunity to

develop a new pursuit generation that would be faster

than the new bombers then under develqpment.

Boeing had already anticipated the advent of the

monoplane pursuit with the Model 96 of 1929, a high-

wing design that the Army financed as the XP-9 for a low

priority experiment using all-metal construction. The

Model 96 number was in the sequence of Boeing design

numbers reaching back to the Boeing Model 1 of 1916.

Not every Boeing design study assigned a number was

built and not every assigned number was given to an air-

frame; there was, in fact, a series of model numbers from

104 through 199 that was reserved for Boeing-designed

airfoils.

The XP-9 proved unsatisfactory aerodynamically, but

Boeing tried again in 1930 with its Model 202 and 204

which were nearly identical all-metal parasol monoplanes

tested by the Army and Navy as the XP-15 and XF5B-1 ,

respectively. Both were essentially conventional biplanes

with their lower wings removed. No orders for these air-

craft were placed.

Following introduction of the revolutionary Monomaif

in May of 1930, Boeing initiated preliminary studies for

a new pursuit, the Model 224, in February of 1931. This

was essentially a scaled-down Monomaif with a similar

low tapered cantilever wing housing a backward-

retracting landing gear, all-metal semi-monocoque con-

struction, P-12E tail surfaces, and a 550 hp Pratt &

Whitney Wasp engine. Old pursuit traditions were main-

tained in the form of an open cockpit.

Informal discussion of the Model 224 between Boeing

and Wright Field representatives aroused little official in-

terest; regardless of major advances the Army had no

requirement for a new pursuit aircraft at the time. Boe-

ing therefore shelved the Model 224 and went b ~ c k to

the drawing board to layout a more simplifiecf design,

the Model 245.

The Model 224 concept was not to die out just yet,

however. It was revamped two years later as the Model

264, which first flew in January of 1934. The Army bought

three examples as the YP-29 for service test, but did not

order the type into production. By that time, with a new

generation of larger, more powerful, and more stream-

lined pursuits on the drawing board, the YP-29's actual-

ly offered too little, too late.

The Model 245 was a wire-braced midwing

monoplane, still with the Wasp engine and open cockpit,

but. with a rigid single-leg landing gear attached to the

fuselage. The basic concept of the forthcoming P-26 was

now established. Wright Field representatives quickly

saw the design's potential and with suggestions and

recommendations, they encouraged Boeing to expand

and develop the studies further. The result was the Model

248, a low wing monoplane with fixed landing gear at-

tached to a stub center section integral with the fuselage

that was very similar in appearance to that found on the

new record-holding Gee Bee racer. The wing was wire-

braced from the landing gear and top of the fuselage.

Wright Field representatives, though still hobbled by

Headquarters budgetary constraints and no specific re-

quirement for a new pursuit, now saw a design that it

wanted.

An ingenious solution to the Army's dilemma was soon

worked out. Boeing would design and build three pro-

totype pursuits and deliver them to Wright Field for Ar-

my testing on a bailment contract as company-owned air-

craft. To reduce initial costs, Wright Field would lend Boe-

ing all the hardware that was normally supplied as

government furnished equipment (GFE) for contracted

military aircraft. This included the powerplant, the pro-

peller, the armament, instrumentation, and other items,

all of which nearly equalled the cost of the airframe in

which it was installed. This proved advantageous to both

parties as it allowed the Army Air Corps to evaluate a

new and advanced design at essentially no cost; and

Boeing took a relatively small financial gamble on a

possible substantial order in the shrunken military and

civil aircraft market of the early Depression Years.

XP-936: Design work on the Boeing Model 248 (the

prototype for the P-26 family) started in September of

1931, under the direction of Project Engineer Robert

Minshall. The Model 248 was later assigned the Wright

Field XP-936 designator. This represented number 936

in a series of experimental aircraft, both military and civil,

tested at Wright Field and its predecessor, McCook Field

back to 1917. Originally, the "P" stood for the word

"plane", but by the time the series reached 9QO, the let-

ter indicated the type of aircraft (as P for Pursuit, B for

Bomber, etc.). The XP-936 designation was assigned

upon signing of the bailment contract for the first three

aircraft on December 5, 1931.

There was a time advantage in developing the new

pursuit as a private venture instead of as Army proper-

ty. As an Army-owned model it would have to incorporate

2

many of the detailed requirements of the Army's bible,

the Handbook of Instructions for Airplane Designers

(HIAD). Boeing was guided by the major requirements

in this publication, but was able to eliminate many of the

lesser ones as being unnecessary for a "proof of con-

cept" prototype.

The first metal was cut on the prototype aircraft in

January of 1932, and in an attempt to speed up the main

construction process, Boeing early-on elected to move

engineers and drafters into the construction area to be

in close proximity to the actual aircraft. Many parts were

actually built from free-hand sketches and on a hand-

fitted basis.

Ten weeks after the cutting of the first metal, the pro-

totype XP-936, cln 1678, was completed at Boeing Field.

This aircraft, with ballast in place of armament and fuel

in the main tanks only, was successfully test flown for

the first time on March 10, 1932, from the company's

Boeing Field, Seattle, Washington facility. A preliminary

evaluation permitted company test pilot Les Tower to

conclude that the new aircraft had excellent flight

characteristics. Following additional test flights under the

auspices of Boeing, Tower, on April 16th, ferried the

XP-936 to Wright Field where it was formally turned over

to the Army on April 25th.

The second XP-936, cln 1679, destined for static test,

was flown away on April 22nd by Lt. L.H. Dawson, an

Army pilot, even though it was still Boeing property. It

reached Wright Field via a circuitous route; March Field,

California, and the Anacostia Naval Air Station,

Maryland. Upon arrival at Wright Field, it entered the

static test laboratory and never flew again as Army pro-

perty. The third XP-936, cln 1680, was flown directly to

Selfridge Field on May 6th by Maj. G. E. Brower for

evaluation by the three squadrons of the 1st PUrsuit

Group.

Oddly, though the XP-936's were company-owned air-

craft, they did not carry civil registrations. Apparently their

military markings and coloring, plus the "XP-936" let-

tering on their tails, qualified them as military aircraft in

the eyes of civil officials and thus legitimized the absence

of civil registration.

XP-26: After the initial XP-936 flight test program was

completed by Boeing and Army pilots (all three aircraft

were officially acquired from Boeing by the Army under

a purchase contract signed on June 15, 1932), the Ar-

my cautiously concluded that the type was indeed a

significant improvement over available pursuits and

therefore a worthy addition to the operational inventory.

Though concern over high landing and takeoff speeds,

overly long takeoff and landing distances, slow response

to throttle retardation, and rapid acceleration in a dive

(considered a negative characteristic at the time!), re-

mained, it nevertheless elected to squeeze production

funding out of an already overburdened budget. A last

minute addition to the 1932 Fiscal Year Budget, which

ended June 30,1932, included funding for an initial P-26

order.

Interestingly, once they became Army property, the

three XP-936 prototypes were assigned a standard US

Army Pursuit-series designator, XP-26, to indicate that

they were technically experimental prototypes (official

acknowledgement of the designation assignment was

consequent to the acquisition of the aircraft on June 15,

1932). Army serial numbers 32-412, 413, and 414 were

assigned at this time, identifying the 412th, 413th and

414th Army aircraft procured in Fiscal Year 1932 (July

1,1931 through June 30,1932).

Y1P-26: As a deviation from standard practice, the

three prototypes did not retain their X-prefixes per-

manently, as was customary for new prototypes. Instead,

the Army decided to change the status of the new air-

craft from "Experimental" to "Service Test", thus requir-

ing the replacement of the "X" prefix with the "Y" prefiX.

To complicate things even further, in some cases, such

as with the three P-26 prototypes, the designation

became Y1 P-26 to indicate that the aircraft were paid for

with the F-1 funds rather than regular Air Corps ap-

propriations. Usually, service test models were procured

on separate contracts and were different aircraft than the

prototypes.

XY1P-26: As a still further oddity, the X and Y1 designa-

tions were combined briefly in August of 1932, as the

XY1 P-26. This was apparently for administrative pur-

poses only, though it must have caused some rather

serious confusion among bureaucrats requiring accurate

designation informationI

P-26: Eventually, all the prefixing designators were

dropped, as was customary in the Air Corps during this

time, and the XY1, Y1, and Y prefixes were removed from

the P, and three prototypes thus becoming simply P-26.

Though the fate of the second P-26 was sealed when

it became a structural test article at Wright Field (being

removed from the Air Corps inventory in September of

1932), the first and third aircraft had relatively long

lifespans. The first P-26 remained at Wright Field dur-

ing most of its flight test and evaluation program, and

then was assigned to Chanute Field, Rantoul, Illinois.

Eventually it was declared "Class 25" and was utilized

for ground crew training. It had ac.cumulated a total of

465 Army flight hours by this time and was eventually

scrapped. The third P-26 prototype shuttled back and

forth between Selfridge and Wright Fields on various test

and evaluation programs before crashing on October 12,

1934, due to the loss of a wing in flight near Baltimore,

Maryland, with a total of 344 Army flight hours in its log

book.

Boeing Model 266: Flight and structural testing of the

three prototypes had led to a number of relatively minor

changes in the production airframes and other systems.

Among these were the elimination of the mainwheel cowl-

ing protrusions visible just behind the rear strut fairings;

a change to smaller-diameter main gear and tailwheel

wheels and tires, and reduced area ailerons. Less

noticeable but of perhaps greater importance were the

various internal changes which included redesign of the

wing structure (though the physical dimensions of the

wing remained essentially unchanged with the exception

of an 11-5/8" increase in span); and provision was made

permitting the installation of Type A-4A skis or Type A-8

wheel-skis as alternatives to the standard landing gear.

In addition to changes brought on by design considera-

tions, there were also areas of contention expressed by

the various test pilots who had been privileged to fly the

two available XP-936 prototypes. Among these were: no

handles or steps were provided to aid a pilot wearing

bulky flying clothes during ingress and egress; the in-

strument panel and engine cowling vibrated excessive-

ly at low and high engine rpm; and some controls were

inaccessible from the seat when the pilot was properly

strapped in place. Additionally, it was noted that forward

vision was obscured during taxi by the Townend ring; and

stability during takeoff, due to the short coupled landing

gear, was marginal. Pilots also noted that normal flight

attitude recovery was slow following pitch change inputs;

an unassisted recovery to level flight during a banking

maneuver at high speed was difficult to obtain and usual-

ly resulted instead in an ever-increasing spiral to the left,

and eventually, a spin; and landing speed (82 mph) and

landing roll-out (350 to 400 yards) were excessive.

P-26A: The initial Army order, placed on January 28,

1933, was for 111 production P-26A's. This was later

amended to include an additional 25 aircraft, thus giv-

ing a total of 136. Unit cost, less GFE, was $9,999, with

total airframe production costs being $1,163,192. A

parallel Army contract with Pratt & Whitney resulted in

an order for 121 R-1340-27 Wasp engines at at total cost

of $540,778.

On November 24, 1933, less than a year after the Ar-

my ordered the production version of the XP-936, the first

P-26A was assembled on Boeing Field. Boeing test pilot

Les Tower made the first flight on December 7th. The

first article, 33-28, was turned over to Air Corps Captain

C. H. Strohm on December 16th, and he promptly took

off for Wright Field. The first P-26A for a squadron, 3330,

left the same day for Barksdale Field, near Shreveport,

Louisiana, piloted by Lt. E. M. Robbins of the 20th Pur-

suit Group. The last P-26, 33-138, would be delivered to

the 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field just over six

months later, on June 30, 1934.

P-26B: The first batch of P-26A's was followed by a

contract revision calling for an additional twenty-five air-

craft, this being the result of a good P-26A service record.

These were identical to the first P-26A's except for the

addition of flaps. Later, as a result of the successful ser-

vice testing of seven Curtiss P-12E's with fuel-injected

R-1340 engines (leading to a temporary XP-12K designa-

tion being applied), Wright Field decided to try fuel-

injected engines on the P-26A. Consequently, the first

two P-26A's in the second production lot were ordered

to be completed with the injected engines. The new

engine was the R-1340-33 which, since it was ap-

preciably heavier Gust over 100 pounds) than the

carburetor-equipped -27, caused ballast to be added to

the tail to maintain proper c.g. requirements. Because

of the extensive system and weight changes involved,

the Air Corps redesignated the R-1340-33-equipped air-

craft P-26B and Boeing consequently assigned a revis-

ed'model number, 266A.

The engine change and the addition of the flaps rais-

ed the unit cost of the two P-26B's to $14,009, less GFE.

The first P-26B, 33-179, was flown to Wright Field for test

'== Ie=>

.j :- - . ; \: MODEL 245

L

-

"'-- ..

,:<\,::r

\. J BOEING MODEL 224

-

:::::--- ----.

Taken in September of 1933, left side-view of P-26A fuselage is seen following application of skin and prior to

attachment of wings, engine and engine mount, tail surfaces, landing gear, and headrest assembly. Large cut-

out for tail wheel is particularly distinctive.

;;" _

A P-26A fuselage is seen in its construction jig immediately prior to the application of external skin. Noteworthy

are the fuselage formers, bulkheads, and stringers. Also note complex jig assembly for positioning and forming

tail wheel cut-out.

I

Main fuselage bulkheads of the first XP-936 are seen aligned in the primary assembly jig during the initial stages

of construction. Drafters and engineers worked side by side with the aircraft as it was built. Photo was taken on

February 2, 1932.

on June 20, 1935. The second, 33-180, was flown to

Selfridge Field on June 21 st, where it became the per-

sonal mount of Lt. Col. Ralph Royce, Commanding Of-

ficer of the1 st Pursuit Group.

P-26C: The remaining 23 aircraft, still with the original

-27 engines, were redesignated P"26C under a Change

Order issued in February of 1936, to indicate the fact that

they had flaps and other minor changes as factory in-

stalled items. The Boeing Model number remained 266.

Later, when the Army decided to refit all the surviving

P-26C's with the fuel injected -33 engines, the designa-

tion changed to P-26B (a rare case of a designation

reverting to an earlier designator). The last flyable P-26B,

33-197, converted from a P-26C, was relegated to Class

26 (non-flying) duty on October 22, 1942, with a total of

1,261 airframe hours.

Since the P-26B's and P-26C's were additional articles

on the original contract, the increased quantity reduced

the basic unit price by $500. The flaps and engine

changes were additional costs above the unit price.

The first delivery of a P-26C was on February 10, 1936,

and the last was on March 7. All were flown to the 1st

Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field. All but six, 33-190, -193,

-196, -198, -201, and -202 (which had been attrited by

mid-1937), were converted to the P-26B configuration at

the Fairtield Air Depot later in 1937. The high-time P-26C-

to-B conversion, 33-183, had 1,952 flight hours. Based

at Wheeler Field, Hawaii, it survived Pearl Harbor and

continued to fly until it was surveyed on May 13, 1942.

RP-26: The RP-26 designation was the result of an Oc-

tober 22, 1942 decision to put certain obsolescent com-

bat aircraft in a new Restricted category that prevented

them from being used for their designated mission, in

this case, Pursuit. The designation applied primarily to

the few P-26A's that remained in squadron service in the

Canal Zone.

ZP-26: The ZP-26 designator was the result of a

December 11, 1942 Army declaration that surviving

P-26A's were too old to qualify for the RP designation.

In so doing, the aircraft were declared obsolete and

designated ZP-26A, accordingly. This was a long

establised designation that had been applied to many ob-

solete tactical types that still had useful lives as testbeds,

squadron hacks and other miscellanea.

Unlike the products of most other aircraft manufac-

turers, P-26's did not simply roll out the Boeing factory

door, taxi out to a runway, and flyaway to their assign-

ed post. To the contrary, the original Boeing factory (Plant

1 after 1936) was a former yacht works on the west side

of the Duwamish River south of Seattle that had no ad-

jacent flying field. The P-26's were built in a WW1 addi-

tion to this plant, and then trucked in a disassembled

state to Boeing Field on the King County Airport located

on the east side of the river some two miles away. There,

final assembly was undertaken in a large brick hanger

leased from the county. Flight testing, consisting of three

hours of shakedown flying by Army service pilots, was

conducted from the airport runway facilities. Delivery to

their assigned units, the 20th, 17th, and 1st Pursuit

Groups (in that order), took place direct from Boeing Field

(export Model 281 's were crated at the factory for sur-

face shipment; from 1937 on, P-26's reassigned to

overseas bases were disassembled, crated, and shipped

by the Army).

Boeing Model 281 (Export): In a further break with prece-

dent, the Army allowed Boeing to sell export versions of

the P-26A before that model had been in Army service

for five years. Though unstated at the time, this decision

also served to confirm that the P-26 was strictly an in-

terim design. Except for minor departures from HIAD re-

quirements and different equipment details, the Model

281 was identical to the P-26A.

The Model 281 was the end result of an in-house deci-

sion on the part of Boeing management to attempt to

penetrate the small but potentially lucrative export

market. Sufficient interest on the part of the Chinese Cen-

tral Government of Chiang Kai-shek led to a commitment

by Boeing to utilize company funds for production of ad-

ditional aircraft over and above those required by the Ar-

my Air Corps.

The first Model 281, painted Army olive drab and

chrome yellow, but"carrying the civil registration X12271

and cln 1959, flew for the firsnime on August 2, 1934.

Shortly afterwards, it was modified by Boeing to test the

wing trailing edge flaps that were later retrofitted to the

P-26A's. also tested a set of revised, open

well wheel fairings, or "pants", on the demonstrator that

allowed the alternate installation of low-pressure

Goodyear Airwhee/s. The latter were incorporated in the

Model 281 in order to accommodate the rough field re-

3

Front view illustrating the first Boeing Model 248, identified as the first of three XP-936's (Boeing cln 1678) by

the US Army Air Corps. The photo was taken at roll-out on March 17, 1932, at Boeing Field. Note location of

pitot boom on left wing.

'.

, .,

quirements expected to emanate from export sales.

Twelve Model.281's were built, with two, X12271 and

X12275, being used as demonstrators. X12271 was

disassembled and shipped to China on September 15th,

but was soon destroyed in a flight demonstration acci-

dent. Fortunately, with the exception of the accident, the

initial parts of the demonstration had gone well and had

left the Chinese with a positive impression. Accordingly,

ten production Model 281's, cln's 1960, 1961, and

1965/1972 were ordered by the Chinese government and

paid for mostly with funds raised by solicitation boxes

in Chinese restaurants in the US. Deliveries of the

Chinese aircraft began on December 12, 1935, and were

completed on January 5, 1936 Gust before P-26C

deliveries began). As shipped to the Chinese, the Model

281's were painted over-all light gray, with the blue and

white Chinese 12-point star only on the undersurfaces

of the wings. Later, they were repainted over-all olive

drab and more complete markings were applied.

The ten Model 281's saw light but significant action

against the Japanese in the Nanking area, where they

were based at Chuying airfield. Japanese efforts to

penetrate south toward Nanking led to the city becom-

ing a primary tamet for G3M2 bombers of the Kanoya

Kokutai which by then were operating out of Taipei,

Taiwan. On August 20, 1937, six G3M2's were destroyed

in the ensuing air battle, with only one Model 281 receiv-

---

ing relatively minor damage.

Unfortunately, spares shortages, accidents, and poor

maintenance qUickly ended the Model 281 's r61e in the

events leading to WW2. By the lime Nanking fell to the

Japanese on December 13,1937, none of the Chinese

Model 281's were still flyable.

The second Model 281, X12275, cln 1962, was

delivered to Barajas airfield, near Madrid, Spain on April

10, 1935, for demonstration to the Aviacio'n Militar under

the direction of Direccio'n General de Aerona'utica.

There, with company test pilot Les Tower and Boeing

Vice President Erik Nelson overseeing reassembly, the

aircraft was made ready for its flight demonstration.

Though they were impressed with the performance of

the Model 281, the Spanish government refused to buy

the type in quantity. The unit price of Pts. 500,000 was

considered too expensive for an already stretched

Spanish military budget. The single Model 281

demonstrator was bought, however, with the idea of

studying its design for potential application to indigenous

fighter aircraft development.

The Model 281 had been delivered to Spain only

minimally equipped. It mounted no guns and there was

no sychronizer gear on the engine. Later, the Spanish

Air Force installed two British Vickers machine guns in

underwing pods outboard of the propeller arc and in-

tegrated the aircraft into a mixed complement Republican

Twenty-six partially completed P-26A's are visible in

this photo taken inside Boeing's production facility

in March of 1934.

fighter unit. It was later shot down over Getafe by Rebel

aircraft on October 21, 1936.

MODIFICATIONS:

As with all high-performance military aircraft, P-26's

were subject to a number of post-delivery modifications

of both minor and major importance. The principal ones

consisted of the following:

Headrest: A Barksdale Field pi lot, Lt. Frederick I.

Patrick, was killed during a forced landing on a routine

cross-country flight on February 22, 1934. Though the

plane, 33-46, flipped onto its back without major struc-

tural damage, the headrest sheared off following the flip-

over and Patrick's neck was broken. This accident

resulted in the February 27th grounding of the entire

28-plane P-26A fleet until a fix could be developed. Since

this was the first P-26A to crash, it was sent to Wright

Field for study and the fuselage was used to static-test

a new headrest.

Boeing and Wright Field worked together to develop

a new higher (8") headrest with substantial inner struc-

ture that could resist a 27,600 lb. vertical load, 13,000

lb. forward load, and a 7,080 lb. side load. Boeing install-

ed the first new headrest on 33-56, which had yet to be

delivered. Aircraft still at the factory were modified there.

with deliveries resuming on March 27th. The others were

modified at Army bases. All work on the headrest

Roll-out day shot of first XP-936. Aircraft had olive drab fuselage with yellow wings and tail surfaces. Vertical fin stripe and rudder stripes were red and white.

Short headrest and fairing are particularly noticeable in this view when compared to the late P-26A configuratIOn. Also dlstmctlve IS the excessive bafflmg VISible on the

nose cowling.

4

The first XP-936 is seen with uncovered P-26A landing gear, the late P-26A headrest, and the original olive drab

fuselage color changed to blue. The photo was taken on August 2, 1936, at the Allegheny Country Airport.

.Ii ....

In spite of Army coloring and markings, all three XP-936's were Baing-owned when tested by the Army under a

bailment contract. This is the seldom-seen XP-936 No.2, photographed at Anacostia NAS on June 1, 1932.

The No. 3 XP-936 is seen during tests at Wright Field still with the early headrest and an over-all olive drab

paint scheme. The pilot is wearing a standard seat-pack type parachute and is holding the small cockpit

hatch that facilitated ingress and egress.

Other accidents resulted from ordnance and equip- craft previously assigned to Barksdale Field and 12

ment. On several occasions, for instance, flares on the previously assigned to Selfridge Field. These equipped

belly bomb rack ignited and set the airplane on fire. On the 3rd Pursuit Squadron which eventually flew the P-26

other occasions, pilot mismanagement of the fuel for no less than five years while successively operating

system, or unpredictable system failures, resulted in out of Clark, Nichols, and Iba Fields. Additional P-26's

engine stoppage and subsequent forced landings. Such were eventually assigned to the 3rd in order to make up

landings, often taking place on unsuitable surfaces, for attrited aircraft, and a surplus led to the re-equipping

made nosing-over almost inevitable. of the 17th Pursuit Squadron with some of its original

OPERATIONS: P-26's when it arrived on Nichols Field in late 1940.

With a few exceptions, all of the P-26's were delivered In the Philippines, 12 P-26A's were transferred to the

from the factory to the operating squadrons of the three Philippine Army Air Force starting in .July of 1941. These

stateside pursuit groups, the 1st, 17th, and 20th. As aircraft were utilized to form the 6th Pursuit Squadron

these premier .organizations acquired later equipment, at Batangas Field, and on December 10th, entered com-

their P-26's were passed on to other groups as indicated bat when a number of Mitsubishi Zero-Sen fighters made

in the accompanying chart. No P-26's were sent out of an initial strafing attack on Zablan Field. Further com-

the country until the spring of 1937, and then only to bat ensued during the following two weeks, with at least

Hawaii, the Philippines, and the Canal Zone. Some'pur- a half dozen P-26's getting involved in air combat with

suit groups activated as late as 1940 were provided with Zero-Sen fighters and G3M bombers. Though hopeless-

obsolete P-26's as initial equipment. It should be noted Iy outclassed by the more modern Japanese aircraft, the

that after 1938, few squadrons having P-26's were fUlly- P-26's miraculously managed to score several victories

equipped with that model alone. before the Japanese landed in force at Limon Bay on

The first overseas deployment of the P-26 took place December 24th. An order to burn the remaining P-26's

in the spring of 1937 with the arrival, at Clark Field, of the 6th Pursuit Squadron, though later rescinded, was

Luzon, the Philippines, of 14 P-26's that included 2 air- unfortunately carried through, and accordingly, all re-

modifications was completed by May 21st.

Stabilizer Gravel Deflectors: Although they looked like

the well-known black rubber de-icer boots, the sheet rub-

ber covering on the lower leading edge of the horizontal

stabilzer was there to prevent gravel kicked up by the

propeller slipstream and the wheels from denting the

sheet metal skin. Because of the rubber, the unique

scalloped paint scheme of the 17th Pursuit Group was

not applied to the underside of the stabilizer.

Wing Flaps: The Army was unhappy with the high 82

mph landing speed of the P-26A. Consequently, both the

government and Boeing developed flaps for retrofit to ex-

isting P-26A's. The National Advisory Committee for

Aeronautics (NACA) designed four different sets and tried

them as simple plywood structures wired onto P-26A

33-56 which was mounted in the full-scale wind tunnel

at Langley Field, Virginia. Wright Field then built what

proved to be the least desireable of the four, a one piece

unit that crossed the fuselage from aileron to aileron and

had a deep bow in the middle to conform to the fuselage

underside when retracted. This was installed on 33-28,

which soon crashed fol' the reasons the NACA had said

it would-blanking of the airflow to the tail at low (land-

ing) speed. A further disadvantage of the one-piece flap

was that it precluded installation of the belly bomb rack.

The Boeing flaps, which were handcranked down to

a 45-deg. deployment angle, were more complex and ex-

pensive than the NACA-developed units in that they were

recessed into the underside of the wing. They were in

four sections, with the ouler ones overlapping the inner

ends of the ailerons. Boeing tested them on the first

Model 281 (foreign sales P-26), and then sent the aircraft

to Wright Field for Army trials.

The Army accepted the Boeing design, which reduced

the landing speed to 73 mph, and starting in the spring

of 1935, cycled the entire P-26A fleet through Boeing's

Seattle facility for the Boeing flap retrofit. The 17th Pur-

suit Group from March Field, just redesignated an Attack

Group and giVing up its P-26's, was the first to send its

P26's to Boeing, and these aircraft, when their respec-

tive retrofit was completed, were then distributed to the

1st and 20th Pursuit Groups. P-26's of the 20th Pursuit

Group were retrofitted next, followed by the 1st. All

P26A's were fitted with the new flaps by the fall of 1935.

Pitot Tube: The pitot tube of early production P-26A's,

mounted on the right wing (the XP-936 had its pitot tube

mounted on the left Wing), was found to oscillate in flight.

An interim measure in which these tubes were shorten-

ed produced a constantly increasing airspeed error which

read up to 13 mph low at 200 mph. The tube was even-

tually replaced with a more rigid, interim length design.

Engine Change: As noted later, the 19 surviving

P26C's were refitted with R-1340-33 fuel-injected

engines in 1937 and were redesignated P-26B. An easy

recognition point was elimination of the two air intakes

for the downdraft carburetor located on the top of the

fuselage, just behind the engine.

Exhaust Stacks: Pilots complained about glare from the

short upper exhaust stacks during night flying, so, star-

ting in October of 1935, the exhaust from cylinders 1,

2, and 9 was fed into a single collector stack that

discharged on the right side of the nose just above the

stack for cylinder 8. The other stacks remained single.

New Tail Wheel: In 1936, Boeing developed a new tail

wheel assembly that featured a smaller wheel with an

oleo-pneumatic shock absorber that projected well below

the fuselage instead of being nested in it. The new style

was adopted in May by the Army and was installed in

the P-26 fleet at Army depots.

Fuselage Reinforcement: Midway through the P-26's

service career skin wrinkles were detected on the

fuselage midway between the cockpit and tail. Starting

in 1935, it became necessary to remove some skin to

perform an internal reinforcement modification. Evidence

of this repair in the form of fresh paint is visible in some

photographs.

OPERATIONAL PROBLEMS:

The P-26 fleet had its share of accidents. The rate was

not significantly greater than for other Air Corps models,

but for some reason the airplane seemed to get more

than its fair share of publicity.

The narrow landing gear, cQl.lpled with the P-26's high

center of gravity, troublesome mechanical brakes, and

"soft" shock absorbers, was responsible for many

ground accidents. If the pilot hit the brakes too hard, or

if one brake locked or faded during application, the air-

craft could easily flip onto its back. If one shock absorber

depressed too far on a cross-wind landing roll, the wind

could get under the high wing and cause a ground loop

that could also easily lead to a nose-over.

5

Mixed w/other models

33-28,33-48,33-52.33-56,33-179; 33-179 wlo 6/20/40;

33-78 trans. to Wright Field 717/40 and wlo 12113/40

(3) 1 P-26 with P-40s.

(4) 1 P-26 with P-36A's.

(5) 2 P-26's with P-40's.

(1)

(2)

NOTES

Activated 10/4/41

Activated 1/1141

Activated 1211140

Activated 12/1/40

P-36A

P-40

P-36A

P-12E

P-12E

P-12E

P-40

P-36A

P-40

P-40

P-36A

P36A

P36A

P36A

P-39

P-39

P-39

P36A

REPLACED

Activa!ed 2/1/40

Activated 2/1140

To Selfridge

11140

Initial Equipment P-36A Activated 1/1141

Initial Equipment P-36A Activated 1/1/41

Initial Equipment P-40 Activated 2/1/40

Initial Equipment P-40 Activated 2/1140

Initial Equipment P-40 Activated 2/1140

33-56,33-57,33-77 mixed wlother models

REPLACED

BY

P6E P-35

P-16 PB-2A

PB-2A P-35

P-6E P-35

P-12E P-40B

Mixed w/P-35A's on transfer from 1st PG

Mixed w/P-35A's

P-12E

Mixed wfP-36A's

(3)

(4)

P-12E

P-12E

P-12E

P-12E

P-12EIF

P-12E

(5)

new squadron

P-12E

P-12E

P-12E

P-12E

Mix w/P-35

Mix w/P-35

Mix w/P-35

The following is a complete listing of all P-26A/B/C US

Army Air Corps unit assignments:

Notes:

(1) fransferred as a new 17th P.S. with the same insignia to Philippines and

re-equipped with P-26's and P-35's.

(2)Activated in February of 1940 in 35th P.G. at Moffett Field with P-36A's.

Transferred to the Philippines and given P-26's and P-35A's.

GROUP SQUADRON P26 STATION

YEARS

1st Pursuit 17th '37'38 Selfridge

27th '34'35 Selfridge

'37'38 Selfridge

94th '34'38 Selfridge

4th Composite 3rd '38'41 Nichols PI

17th '40'41 Nichols. PI

20th '40'41 Nichols. Clark PI

15th Pursuit 29th '38-'39 Canal Zone

45th '40-'41 Wheeler TH

46th '41 Wheeler TH

47th '41 Wheeler TH

16th Pursuit 24th '39 Canal Zone

17th Pursuit 341h '34-'35 March

(to 17th Attack Group 73rd '34'35 March

3-135) 95th '34'35 March

18th Pursuit 61h '41 Wheeler TH

19th '38'41 Wheeler TH

44th '41 Wheeler TH

73rd '41 Wheeler TH

78lh '40 Wheeler TH

20th Pursuit 55th '34'38 Barksdale

77th '34'38 Barksdale

79th '35'38 Barksdale

31st Pursuit 39th '40 Selfridge

40th '40 Selfridge

41st '40 Bolling

32nd Pursuit 51st '41 Canal Zone

53rd '41 Canal Zone

37th Pursuit 28th '40-'41 Canal Zone

30th '40'41 Canal Zone

31st '40-'42 Canal Zone

Bolling Field '34'36 Bolling

Air Corps Detachment

Air Corps '34'37 Chanute

Technical School

MaterIel Division '33-'40 Wright

maining aircraft were destroyed.

During 1938, P-26's were assigned to Wheeler Field,

Hawaii, and Albrook Field, Panama Canal Zone. No less

than 42 P-26's were sent to Hawaii to equip the 18th Pur-

suit Group (6th and 19th Pursuit Squadrons), though

some 20 of these were later reassigned to the Philippines

during late 1938 and early 1939.

As the P-26's entered service in Hawaii, additional air-

craft were being assigned to Aibrook Field in the Panama

Canal Zone where they equipped the 16th Pursuit Group

(24th and 29th Pursuit Squadrons). These aircraft pro-

vided the primary Canal air cover until supplanted by Cur-

tiss P-36A's in 1940.

Eleven P-26A's remained in the Panama Canal Zone

in 1940, and most of these were eventually transferred

to a US Army organization known as the Panama Canal

Department Air Force (often referred to as the Panama

Air Force) which, in turn, sold some of them to Guatemala

for use by the Cuerpo de Aeronautica Militar. These air-

craft were suppiemented by an additional four P-26A's

which were acquired directly from the Air Corps.

Guatemalan P-26's were reassigned to the Escuadro'n

de Caza at Camp de la Aurora, Ciudad de Guatemala

and utilized as front line fighters and advanced trainers

for most of their Guatemalan careers.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor debacle, there were

only four P-26's left in the continental US. Additionally,

there were seven in Panama, eight in Hawaii, and six

still in US service in the Philippines. Altogether, 31

P-26A's and 14 converted P-26B's were sent to Hawaii,

34 P-26A's to the Philippines, and 26 P-26A's to Panama.

The service career of the P-26A in Air Corps service

spanned just under a decade. The last flyable example

in US Army service, 33-89, was transferred to the

Guatemalan Air Force from Albrook Field, Canal Zone,

on May 4,1943, with 2,302 flying hours in its log books.

The high-time US Army P-26A was 33-122. Unfortunate-

ly, it was written off following an accident in Panama in

June of 1942 with some 2,550 hours logged.

P26A/B/C OVERVIEW:

Clean P-26A warms up for mission. Aircraft has extended headrest and fairing and

is apparently painted in conventional scheme of olive drab with yellow wings.

A P-26A is seen in conventional markings at an unidentified airfield in New York on

March 15, 1934. In this view the height of the modified headrest is readily apparent.

A line-up of P-26A 's with the first aircraft providing a view of the Boeing-designed

flaps in their extended position.

Gl

"'

~

))

, s:

i.

8

~

~

~ .

~

~

~

) . ~

<:

I "

.- \

2

0

~

g'

This P-26A lacks the forward cowling-mounted radio antenna mast that is so promi-

nent on most "Peashooters". Vertical fin antenna mast is visible.

6

The first P-26A, 33-28, at Wright Field, displaying the Wright Field arrow insignia on the fuselage. Panchromatic

film has caused darkening of yellow wings and red and blue tail markings.

Top view of the first production P-26A, 33-28, taken on delivery day, December 16, 1933, at Boeing Field.

Revised elliptical wing shape is particularly noticeable. Panchromatic film gives light-color accent to yellow-

painted wings and tail surfaces.

Other not.able differences between the P-26A (Boeing Model 266) and the XP-936 were revised landing gear fair-

ings, a pitot mast on the right wing (instead of the left), a higher headrest, and flush instead of brazier-head

rivets. Aircraft 33-28, shown, had antenna masts installed, but no radio.

INDIVIDUAL AND UNIT MARKINGS:

Most P-26's in squadrons or special organizations car-

ried that organization's insigne on each side of the

fuselage. Aircraft attached to group headquarters carried

group insigne. A notable exception, from 1934 to 1939,

was the 20th Pursuit Group. All three 20th PG squadrons

carried group rather than squadron insigne.

Individual aircraft were numbered separately within the

group. The 1st Pursuit Group had a unique system; the

last two digits of t ~ e Air Corps serial number were painted

on the vertical fin and engine cowling of its P-26's. The

P-26's of the 17th Pursuit Group were numbered 1-18 for

the 34th Squadron, 32-60 (with gaps) for the 73rd, and

61-90 for the 95th. Group headquarters aircraft were

100-103 and the Wing Commander's aircraft was 00.

Confusion exists from the fact that former 17th Pursuit

Group P-26A's which went to the 1st and 20th Groups

retained their original 17th P.G. color schemes but got

new identification numbers in their new groups.

The P-26A's of the 20th Pursuit Group were first iden-

tified by big white block numbers 0-48 on the fuselage.

These were changed to black numbers on the fin and up-

per left wing in 1935. Usually, but not always, the last

two digits of the serial number were preceded by the

number 1 for individual aircraft identification. Other

groups that had hand-me-down P-26's used more ar-

bitrary tail numbers.

From 1938 into 1940, the system changed. Groups

were identified as to type and number by letters, as PT

for the 20th Pursuit Group, T being the 20th letter of the

alphabet. The aircraft number was carried below the let-

ters on the fin and following them on the upper left wing,

now for all groups. In 1940, the system was revised to

use the actual group number, as 18P for the 18th P.G.

This time the aircraft number was above the group iden-

tification on the fin. The 18th P.G. in Hawaii misapplied

the new designator as 18 PG instead of 18 P.

Application of squadron colors, leader stripes, etc., was

not standardized for most of the P-26 era and cannot be

detailed nere. Some comments on this subject, however,

appear in the photo captions.

THE SURVIVORS:

Two of the Guatemalan P-26A's, 33-123 and 33-135,

were still intact in 1957. Both were eventually retrieved

for display in the US and are currently displayed in the

colorful markings of the 34th Pursuit Squadron of the

17th Pursuit Group (though neither airplane is known to

have served with the 17th PG).

P-26A, 33-123 was first delivered to the 94th Pursuit

Squadron at Selfridge Field on June 20th, 1934, and was

marked as Plane No. 23. It was soon transferred to Group

Headquarters and flown with group, rathQl' than squadron

insigne. A nose-over accident occurred in September of

1934, and repair was undertaken at Fairfield Air In-

termediate Depot. In August of 1938, it was sent to the

San Antonio Air Depot for a major overhaul, and from

there, it went to Rockwell Field, San Diego, for

disassembly and shipment to the Canal Zone.

It was retired from Albrook Field, CZ, in August of

BASIC MARKINGS:

Four basic US Army color schemes were used during

the P-26's service career. As originally buill, they all had

chrome yellow wings and tail surfaces with olive drab

(o.d.) fuselages and landing gear. In May of 1934, a

Technical Order was issued calling for the replacement

of the o.d. with a shade called Light Blue. The latter was

actually a medium blue and because the change was not

required to be immediate, manufacturers were permitted

to consume existing stocks of o.d. paint before chang-

ing to the new color. Although P-26C's were delivered

as late as March of 1936, no Boeing employee can recall

ever having seen a blue-painted aircraft in the factory.

In 1938, with many newall-metal aircraft entering ser-

vice in natural metal finish, over-all silver was decreed

as the standard coloring for tactical aircraft. Some older

blue and yellow models still in service were repainted at

squadron level. Again, there was no hurry, and relative-

ly few P-26's found their way into silver paint.

Starting in February of 1941, tactical aircraft in the

squadrons were repainted in o.d. on their top and side

surfaces and with light gray undersurfaces. The old Army

tail stripes were deleted, as were the upper right and

lower left wing stars. Additionally, a star was added to

each side of the fuselage. Very few of the P-26's still in

service at that time were given the new arrangement.

Some in the Philippines were still in silver or even blue

and yellow after the Japanese attack on December 8,

1941 (the date in the Philippines).

7

Another view of 33-28 at Wright Field. Again, orthochromatic film has caused darkening of the yellow wings and

red and blue tail markings. Note that both wings had Air Corps star.

Five P-26A's are seen lined up on Boeing Field in June of 1934. These aircraft have the new high headrest but

no radio masts. All P-26A's were flown away without radios. Note the variety of flying clothes being worn by the

Air Corps ferry pilots.

The first P-26B, rolled out on June 29, 1935, was identical to the P-26A except for the addition of wing flaps

and the change to a fuel-injected engine. Visible in this view are the split flap sections.

Three-quarter rear view of the first P-26B. The vertical fin, horizontal stabilizers, elevators, and wings were

painted yellow. The fuselage was olive drab and the rudder was red and white with a large vertical bar of blue.

8

1943, after logging some 2,454 flying hours. From

Albrook Field it was transferred to Guatemala. In 1957,

it was acquired by Edward T. Maloney of California, who

brought the airplane back to California for display in his

new aviation museum which was then located near

Claremont, California (the museum has since moved to

Chino, California). After several years of static display

it was restored to flying condition and painted in the 34th

Pursuit Squadron markings (but with its correct 1st Pur-

suit Group Number 23). F(}jlowing restoration, it took to

the air for the first time on September 17,1962. Flown

occasionally since, it is presently the only flyable P-26

in the world. The fuselage is painted blue (which no 17th

Pursuit Group P-26 ever was).

The only other surviving P-26, 33-135, was delivered

to the 94th Pursuit Squadron at Selfridge Field on June

27th, 1934, and was marked No. 35. After an accident-

free career, it too was sent to San Antonio for overhaul

and to Rockwell for disassembly and shipment, in

September of 1938, to Panama. It was sold to Guatemala

in August of 1942, having logged 2,552 flight hours, and

was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution shortly after

Maloney acquired 33-123. It was then placed' on long-

term loan to the AF Museum, which restored it as NO.7

of the 34th Pursuit Squadron. Accurately painted with an

olive drab fuselage, 33-135 was displayed at the AF

Museum from 1959 thru 1975. It is now hanging in the

National Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

CONSTRUCTION AND

SYSTEMS:

As the Army's first all-metal pursuit aircraft, the P-26

series utilized structure developed by Boeing on its earlier

Model 96/XP-9, the Model 200 and 221 Monomail single-

engine transports, and the Model 214 and 215 (which

became the Army's B-9 bomber). Design experience in

this new area remained limited and accordingly, the struc-

ture was not only very conservative, but was also highly

redundant and considerably overweight.

The fuselage was a semi-monocoque structure with

load carrying aluminum skins flush riveted to six main

bulkheads and 13 intermediate formers. These formers

and the interconnecting longitudinal members were rolled

to a hat-section from flat aluminum sheet. The fuselage

cross-section was roughly tear-shaped at the front,

changing to a nearly oval shape at the tail. It was

necessary to install a small hinge-down door to simplify

pilot access.

Because there were no straight lines to the P-26

fuselage, the sheet aluminum skins could not be put on

in large flat-wrapped sheets. Instead, the skin was put

on in long narrow longitudinal strips, starting at the bot-

tom with the higher skins overlapping shingle-fashion.

The tighter curves of the nose ahead of the firewall were

formed on hydropress dies.

The engine mount was a separate removable steel tube

frame that was bolted to the No. 1 bulkhead. Rubber

bushings in the forward mounting ring dampened engine

vibration. The required design loads for the fuselage were

12.0 positive and 8.5 negative, and the XP-936 passed

these with 13.39 and 9.5, respectively. The static testing

was not carried to the point of destruction because it was

desired to save the fuselage for other tests.

The wing, which utilized a Boeing 109 airfoil, was built

in three sections consisting of two removable outer

panels and an integral stub center section to which the

landing gear was attached. The wings used two main

spar assemblies built up of flat sheet aluminum and

riveted-on flanges. Ribs were built up of rolled hat sec-

tions and short aluminum tubes with their ends flattened

for riveting. The wings were covered with sheet aluminum

riveted in place. Brazer-head rivets were used on the

Model 248/XP-936 and flush rivets were used on all other

models.

Wing design loads were 12.0 positive and 4.0 negative.

At the high angle of attack condition, the wing passed

without failure. In the inverted position, it was overload-

ed by 25% to a factor of 5.0 without failure. The flying

wires tested from 13.0 to 14.25 before failure.

The cantilever fin and horizontal stabilizer used a

semblance of the traditional spar-and-rib construction

technique. There was a hinge-line spar of aluminum

channel and a similar diagonal spar. These were con-

nected by four traditional ribs. Other ribs ahead of the

diagonal formed the leading edge. Each structure was

covered with sheet aluminum. There was no fixed leading

edge structural member; the upper and lower skins were

flanged aDd flush-riveted to each other. The ribs served

mainly as spacers for the skins rather than as traditional

compression members. Except for use of smooth instead

of corrugated skins, this detail was a direct inheritance

from earlier Boeing pursuits and fighters dating back to

the Navy F3B-1 of 1927.

In spite of redundant structure, the horizontal stabilizer

did not test well, showing impending failure at 90% of

the design load of 253 lbs. per sq. foot. Reinforcement

was added in order to meet the load requirement and the

unit eventually passed the test. The vertical fin withstood

130% of the 189.6 lbs. per sq. foot design load without

failure.

The elevators, rudder, and ailerons differed notably

from the fixed surfaces. Each had a channel spar at the

hinge line but the ribs were pressed aluminum diagonals

that again served mainly as spacers for top and bottom

skins that were riveted to each other at the trailing edges,

again an element inherited from earlier Boeing designs.

The elevators had a Handley Page balance area ahead

of the hinge line (inherited from preceding Boeing pur-

suits such as the P-12B/F4B-2 and on). The ailerons were

similar in design, but were of the Frieze type wherein a

portion of the upward moving aileron projected below the

lower surface of the wing to add drag on the inside of

the turn and reduce "adverse yaw" phenomenon.

Each elevator was fitted with a trailing edge tab that

was controlled from the cockpit to correct the longitudinal

trim-a first for a production American aircraft. It had

been developed in Europe and Boeing pioneered its use

in the US. The tab was irreversible under air load, being

actuated by a screw. Displacing the tab upward caused

the airstream to deflect the elevator downward, thereby

trimming the aircraft nose-down. Previously, longitUdinal

trim had been obtained at the cost of mechanical com-

plexity by rotating the entire horizontal stabilizer about

the rear spar line.

Trim for both ailerons was by means of fixed sheet

aluminum tabs extending beyond the trailing edge and

adjusted by hand on the ground. A similar rudder tab was

added to the P-26A later.

The landing gear was a complex structure consisting

of a rigid V-frame connected to both wing root spars and

anchoring the flying wires at the iower point. Shock ab-

sorption was by means of a Boeing-built oleo-pneumatic

shock strut pivoted at the toplfront spar junction, and held

forward of the low point of the rigid "V" by a pivoting arm.

On the XP-936, each wheel was mounted in a fork, which

required removal of the axle in order to remove a wheel

or change a tire. This was soon replaced by a mislabelled

"single leg" unit that secured only the inboard end of the

axle, allowing the wheel to be slipped off easily.

Since the wire braced system was unstable with the

wing wires slacked off or removed, it was necessary to

install a spreader bar between the two landing gear units

and keep the inboard crossed wires tight.

Braking was mechanical land actuation was by toe ac-

tion at the top of the rudder pedals. For parking, the

brakes were locked by means of a handle on the pilot's

auxiliary instrument panel.

Streamlining involved spacers between the arms of the

"V" to support aluminum skins. The upper portion of the

shock strut was covered by wraparound sheet aluminum

fastened to the V-leg, but the formed wheel pants were

attached to the shock strut and moved with it. Spacing

from the fixed fairing was maintained by rub strips. It

became common practice in some squadron operations

to remove the outboard side paneis of the multi-sectioned

"pants" for flight.

Armament was the Air Corps standard of two .30

caliber Browning machine guns firing through the pro-

peller, each with 500 rounds of ammunition, or one .30

caliber M-2 on the left side of the cockpit floor and one

.50 caliber M-2 with 200 rounds on the right. The guns

were modified so that the left-hand gun was fed from its

right side while the right-hand gun was fed from the left.

Ammunition boxes were underneath the floor ahead of

the 55-gallon fuel tank. The guns were charged by pull-

cables with T-handles at each side of the pilot's seat

back. The electrical firing circuit was controlled by a

selector switch on the pilot's aUXiliary panel. Ammunition

counters for each gun were on the same panel. The

single gun trigger was built into the forward side of the

control stick grip.

A type C-3 gun sight was mounted ahead of the wind-

shield and a type G-4 camera gun could be installed on

the top of the right-side wing stub. Power for the camera

gun was provided by two dry batteries carried in the right-

side ammunition box. A standard Air Corps Type A-3

bomb rack, capable of holding two 100 lb. demolition

bombs, five 3D-lb. fragmentation bombs, or two parachute

flares, was installed under the belly.

Two-way voice radio was just coming into use when

the P-26A's entered service. The standard radio was the

low-frequency SCR-( )-183 radio. The letters SCR iden-

tify Signal Corps Radio and the blank parenthesis are fill-

ed by letters indicating the particular manufacturer of the

set or component.

The BC-( )-180 transmitter was located on the cockpit

floor ahead of the control stick and beneath the auxiliary

panel. The control box was on the left side of the cockpit

above the throttle. The SCR-( )-192 receiver was in the

baggage compartment on the right side of the bulkhead.

The tuning controls were on the right side of the cockpit

opposite the transmitter control.

There were two separate antenna. A mast ahead of the

windshield supported transmitter wires running to each

wingtip. A short mast on the top of the vertical fin sup-

ported the longitudinal receiver antenna wire. Only pro-

vision for radio equipment was made at the factory; radio

was installed by Army personnel at squadron level.

The P-26 was a pioneer in the use of a liquid oxygen

system for high-altitude work. A Type B-11 vaporizer and

storage bottle were mounted on the backside of the

cockpit rear bulkhead, to the left of the zippered canvas

baggage compartment. An access door in the side of the

fuselage made it possible to service the system with the

vaporizer and storage bottle in place. The pressure gauge

and adjusting needle valve were clamped to the right

edge of the pilot's instrument panel.

After P-26A deliveries began, the Army decided that

emergency flotation gear was desireable. Aircraft 33-52

was then pulled from the inventory to serve as a testbed

and accordingly, two bags were installed in streamlined

aluminum "slippers" attached to the upper surface of

each wing stub. The carbon dioxide bottle was installed

to the left of the pilot's seat and actuated by a cable and

T-handle in the left rear corner of the cockpit. An

emergency hand pump was carried in the headrest.

It was necessary to contour the bags to fit around the

landing wires above the wing. All P-26's from 33-53 and

on had provisions for flotation gear built in at the factory.

Earlier aircraft from 33-28 thru 33-51, were not retrofitted.

Because of the externai "bolt-on" nature of the flotation

system, problems of being stepped on, and interference

with the camera and gun installation, the flotation bags

were seldom installed. At least one P-26A was lost when

one of the flotation bags came open in flight.

POWERPLANT:

In choosing an engine for the P-26, Boeing selected

one that it had been using in pursuit and fighter aircraft

since 1926. The Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp had long

held a reputation for dependability and ruggedness, and

though it was not a state-of-the-art design, it \'las none-

the-less determined to be suitable for Boeing's new pur-

suit by the company powerplant staff.

The R-1340 (R = radial; 1340 = piston displacement

to the nearest five cubic inches) was a nine-cylinder, air-

cooled radial rated at 550 hp. More powerful, but also

larger and heavier engines were available, but were not

suited to the design concept of the P-26. The competing

Curtiss XP-934 Swift, for instance, started with a 700 hp

Wright R-1820F Cyclone air-cooled radial, but shortly

afterward, had it replaced by an older 600 hp Curtiss

V-1570 Conqueror liquid-cooied V-12.

The Wasp was designed by engineers who had left the

old Wright Aeronautical Corporation to design a better

air-cooled radial. They received initial encouragement

and orders from the US Navy, which saw and quickly ap-

preciated the weight-saving and reliability advantages of

conventionai air cooling.

Throughout the 1920's and into the early 1930's, ser-

vice engines were identified by the makers' designation

such as R-1340B, 1340C, etc. The addition of a super-

charger would be indicated by a prefixing S, such as

SR-1340D. The XP-936 in fact used the SR-1340E, which

delivered 522 hp at 2,200 rpm at 10,000 feet through a

two-blade ground-adjustable fixed-pitch propeller.

By the time the P-26A entered service in 1934, the

Army and Navy had adopted a new system separate from

the manufacturers'. The basic type and displacement

figures were retained, but the stage of development was

identified by sequential dash numbers with "even

numbers" being set aside for Navy engines and "odd

numbers" being set aside for Army. The P-26A's and C's

used the R-134D-27. Interestingly, though this engine was

supercharged, it did not incorporate the S-prefix in its

designator.

The P-26B used the R-1340-33, which had direct fuel

injection instead of carburetors and a new control lever

in the cockpit that COmbined the functions of throttle and

mixture control into one unit. Fore-and-aft movement con-

trolled the throttle, while rotation of the knob enriched

(counter-clockwise) or leaned (clockwise) the mixture.

Because of the altitUde supercharging, the engines in

the P-26's were limited to less than full power below 6,000

feet by a throttle stop. Sea-level output of the R-1340-27

(P&W's R-1340-S2E) was 500 hp at 2,200 rpm for takeoff, .

and 570 hp at 2,200 rpm at 7,500 fee.t.

The engine was equipped with an inertia starter crank-

ed by hand or with a powered flexible shaft engaging a

drive on the left side of the nose. The "engage" handle

was in the cockpit to the left of the instrument panel. In

the P-26's, the engine was enclosed in a Boeing varia-

------ -

A P-26B sits on the ramp at Boeing Field. This aircraft does not have an antenna

mast and appears to be seen prior to delivery.

The twenty-three P-26C's were identical to the P-26A's except for minor equipment

differences and the fact that they were built with flaps. This one is seen outside the

Boeing factory in early 1936.

9

tion of a Townend "anti-drag" ring and the forward

crankcase was covered by a unique Boeing oil-cooler-

shutter assembly that Boeing called a nose cowling.

Fuel was carried in three tanks: a 55-gallon main tank

in the belly and one removable 26-gallon auxiliary tank

in the root of each outer wing panel. The last 20 gallons

in the main tank were considered the reserve supply. A

single fuel tank selector (there were two on the XP-936

and the early P-26A's) was mounted on the auxiliary

panel. The handle for the manual fuel pump used in star-

ting was mou nted on the left side of the cockpit on the

same mount as the elevator trim control.

An eight-galion oil tank was installed ahead of the no.

1 bulkhead. The oil circulated from the engine back to

the tank through a core-type cooler installed below the

engine accessory section.

SERIAL NUMBERS:

The three XP-26's were given Army Air Corps serial

numbers A.C. 32-412 through 32-414. Air Corps serial

numbers for the 111 P-26A's were 33-28 through 33-138,

paralleled by Boeing c/n's 1804 through 1914. The 25

follow-on aircraft were 33-179 through 33-203, though the

Boeing c/n's were not in parallel. The two P-26B's were

33-179 and 33-180, but their Boeing c/n's were 1919 and

1916, respectively. Aircraft 33-181 through 33-183 were

P-26C's with Boeing c/n's 1915, 1928 and 1917, respec-

tively. P-26C's 33-184 through 33-191 were matched by

Boeing c/n's 1920 through 1927, but aircraft 33-192 had

c/n 1918. The remaining P-26C's, 33-193 through 33-203,

had matching Boeing c/n's 1929 through 1939.

SPECIFICATIONS AND

PERFORMANCE:

XP-936 P-26A P268 P26C

Fuselage length 23'5.13" 23"7.25" 23'9" 23'9"

Wingspan 27'0" 27'11.6" 27'11.6" 27'11.6"

Wing area (gross) 150.0 sq.' 149.5 sq.' 149.5 sq.' 149.5 sq.'

Wing aspect ratio 4.86 5.21 5.21 5.21

Wing loading

(Ibs.lsq.) 18.26 19.76 20.45 20.56

Height (tail up) 9'4.5" 9'4.5" 9'4.5" 9'4.5"

Height (tail down) 10'5" 10'5" 10'5" 10'5"

Wheel track 5'1,5" 5".5" 5".5" 5".5"

Wheel base 15.0' 15.0' 15.0' 15.0'

Empty weight 2,070.5 2,196 2,301 2,332

Ibs. Ibs. Ibs. Ibs.

Gross weight 2,740 2,955 3,060 3,074

Ibs, Ibs. Ibs, lbs.

Max. speed @

optimum alt. 222 234.0 235 235

mph mph mph mph

Max. speed @ 5.1. 211 211 215 215

mph mph mph mph

Service ceiling" 30.700' 27,400' 27,000' 27.000'

Absolute ceiling" 31,600' 28.300' ? ?

Rate of climb

(per min.) 2.260' 2,360' 2,300' 2,360'

Range 358 mi. 635 mi. 635 mi. 635 mi.

Please nole that because of differenl methods of testing and calculation, per-

formance figures obtained by Boeing and Wright Field for the same aircraft

are not always identical. The figures presented here are from Boeing.

AVAILABLE SCALE MODELS

AND DECALS:

The following is a complete listing of all known P-26

plastic kits and decals:

Kits

1I100th: AHM

1I72nd: Advent, Revell

1/48th: Aurora, K&B

Decals

Microscale: 1J32nd-32-31

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHS:

The photographs used In Minigraph 13 reflect the state-

of-the-art In photography at the time the P-26 was in ser-

vice. Of course there was no significant color

photography in the 1930's when the P-26 was in its hey-

day, so all P-26 photos, with few exceptions, were taken

in black and white. The color photos used in Minigraph

13 depict the two surviving P-26A's, both of which are

wearing notably inaccurate markings and color schemes.

Aircraft were not photographed extensively by the

government in the 1930's. The manufacturer took

"around-the-clock" and detail views for his own records,

in support of required customer documentation and

limited pUblic relations work. The customer-in this case

the US Army Air Corps-also took its own identification

views at Wright Field when prototypes and early produc-

tion models were sent there for testing.

The user organizations, most notably the squadrons,

were also short on conventional aircraft photos. Most

squadron-related imagery tended to subordinate the air-

craft to the people who might be involved. In-flight views

were usually reserved for the more spectacular images,

most notabiy long shots of the aircraft in formation.

It therefore remained for the amateur enthusiasts and

photo collectors, who had easy access to Air Corps bases

in those relaxed days, to photographically document pro-

duction aircraft in operational settings. Concern about

markings, multiple views of the same aircraft without

. background distraction, closed doors, and centered con-

trols, helped push the quality of amateur aircraft

photography to a level on par with whatever could be ob-

tained from more professional sources. Any markings

change was a valid reason for enthusiasts to shoot the

same aircraft more than once; companies and govern-

ment agencies rarely bothered.

The majority of the collectors and enthusiasts in the

1930's used a standard folding camera that required size

616 film. This produced negatives that were approximate-

ly 2-3/4" x 4-

1

12 "-ideal for the oblong proportions

presented by aircraft sitting static on the ground. Before

616 roll film was discontinued in 1975, most collectors

had already switched to the more convenient 35mm

format.

There were basically two types of black and white film

available in the 1930's. Verichrome, the cheapest, was

an orthochromatic film that made red appear to be almost

black, yellow to appear very dark, and blue to appear

significantly lighter in the positive print. A faster and more

expensive film was Super-X, which was a panchromatic

film that rendered red as a light shade of grey, blue as

a darker shade, and yellow as almost white. These

characteristics were particularly noticeable when Super-X

was used with an amber filter..

Collectors, as Is often the case today, shot negatives

not only for their own files, but also for others with whom

they traded. This trading, which in the case of many

photos in this book took place nearly a half-century ago,

today causes problems in determining accurate credit

lines. A print supplied by one collector could easily have

been made from a negative taken by another. This pro-

blem is made significantly more complicated by the fact

that some negatives, during the half-century that has

passed since they were taken, have passed through

many hands, with the name of the original photographer

having long ago been lost in the trading process. Accor

dingly, the majority of the photos in this book are a mix