Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

1236502

Cargado por

Benni WewokDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1236502

Cargado por

Benni WewokCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Agricultural & Applied Economics Association

Shaping the World Economy: Suggestions for an International Economic Policy by Jan Tinbergen Review by: John W. Mellor Journal of Farm Economics, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 271-273 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1236502 . Accessed: 18/03/2013 09:21

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Agricultural & Applied Economics Association and Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Farm Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Mon, 18 Mar 2013 09:21:31 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVEWS

271

Tinbergen, Jan, Shaping the World Economy: Suggestionsfor an International Economic Policy, New York,The Twentieth Century Fund, 1962, pp. xviii, 330. (Cloth, $4.00; Paper, $2.25) In this book, Tinbergen and his staff at the Netherlands Economic Institute give a readable, essentially popular presentationof their views as to the nature of the world's majorproblemsand their prescriptionsfor solution of those problems. With the exception of an interesting empirical analysis of trade patterns, the book does not attempt to chart new ground in regard to either theory or empirical evidence. It is however valuable to have the judgment of a person of Tinbergen's experience and stature in regard to the many controversialissues treated. Tinbergen'swide-ranging conclusions emphasize the need for: (a) a large increase in foreign aid by the developed countries, with the United States providing 60 to 70 percent of the coverage a la the suggestions of (b) rapid progress towards free trade, with the exception Rosenstein-Rodan;1 of temporaryduties in low income countries and some agriculturalprotection in the developed countries; (c) reduced internal taxes in developed countries on the products of tropical areas; (d) more and better internationalcommodity agreements; (e) increased economic integration within geographic regions; (f) a greatly enlarged role for the United Nations, particularlyin regard to development planning and projections; (g) a greatly enlarged role for the nonaligned nations in determinationof policy as well as in its execution; and financialand monetaryauthorities.These (h) the developmentof supranational latter would serve as a world central bank a la the suggestionsof Robert Triffin2 (although Tinbergen would prefer Meade's3suggestion of fluctuating exchange rates if they were acceptable to national central bank managers);they would coordinate and redress imbalances in national allocations of aid and development funds; they would stabilize revenues of countries producing primary commodities, and they would provide insurance against noneconomic risks of private foreign investment.The importanceof planning at the national and international level is emphasizedthroughoutthe book. The book is concerned largely with economic development since Tinbergen sees this as the keystone problem in the world economy. Part one discusses the nature of underdevelopment,the "two competing systems ... the Western and and existing trade and commodityproblems.Part two delinethe Communist," ates an optimal internationalpolicy in regard to objectives, investment problems, trade and commodity policy and international institutions. The appendices provide a "lightly once over" treatment of the four major underdeveloped regions of the world plus detail on the analysis of trade flows and quantificationof the consequences of various tariff and excise tax reductions.

Rev. Econ. and Stat., May 1961, pp. 107-138. 2 R. Triffin, Gold and the Dollar Crisis-Future of Convertability, New Haven, 1960. 'J. E. Meade, "The Future of International Trade and Payments," The Three Banks Review, June 1961.

"International Aid for Underdeveloped 1P. N. Rosenstein-Rodan, Countries,"

This content downloaded on Mon, 18 Mar 2013 09:21:31 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

272

REVImws

In an attempt to cover a wide area efficiently and in a manner intelligible to a broad audience, the book admits a looseness of definition likely to distress many readers, viz: "we must realize that most of the people in Asia and Africa and many in Latin America are living at a starvation level" and "surely the tropical and subtropical climates . . . are not conducive to persistence or to productivity generally." Tinbergen subscribes to the "big push" school of development with its ancillary of the "vicious circle of poverty." This position leads clearly to his conclusion that an adequate rate of growth of 2 percent per year in the per capita income of underdeveloped areas will require additional investment of 7 to 8 billion dollars per year, and that this increment will have to come in the form of aid from the developed areas. This incremental sum is equivalent to 1 percent of the total national income of developed countries and would require roughly a doubling of annual foreign aid expenditures. It is perhaps in regard to foreign aid that this book falls furthest short of meeting the crucial issues of the day. Tinbergen provides elegant support for aid on the grounds of equity, welfare and world power politics. He does not use the argument that, in the long run, development might provide the basis for greater world efficiency in production and hence direct economic advantages to the developed nations. But, more important, his treatment does not recognize that recent growth in American criticism of foreign aid has come not so much from growing parochialism and a decline in concern for welfare of others as from a feeling of frustration in achievement from foreign aid. There is a good deal of evidence that this frustration is based on real failings rather than on excessively high expectations. Thus, an increase, or even maintenance of current aid levels, demands measures for increased effectiveness of aid. Tinbergen gives few positive suggestions for improving the effectiveness of technical aid programs. This is doubly unfortunate because technical aid includes some of the best opportunities and the greatest failings in aid programs. And, unfortunately, his argument (p. 126) for equalization of rates of growth as the basic criteria for aid may reduce the efficiency of capital grants. The returns may be low in the case of governments which will not take the requisite developmental steps and countries which are short of infrastructure, particularly trained manpower. In the long run it may be more efficient to give a modest total of aid, emphasizing manpower training, to countries shortest of manpower and infrastructure and heavy capital credits to the countries providing higher short-run returns due to a more developed infrastructure. Although this may or may not widen income gaps in the short run, it appears to provide a better framework for current policy than Tinbergen's more heavily equity-oriented prescription. In an interesting preliminary analysis, Tinbergen measures the extent to which "today's pattern of international trade deviates from the most desirable quantitative structure." On the assumption "that trade between most pairs of countries is not restricted and can therefore be considered as an indication of the most desirable volume of trade," equations are used to calculate the normal volume of trade for each of 42 countries. The determinants of the

This content downloaded on Mon, 18 Mar 2013 09:21:31 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS

273

normal pattern of trade among pairs of countries are the size of the exporting and importing country as measured by GNP and the geographic distance between countries. Calculations of the coefficients were made for various sets of countries, the largest set being 42, and comprising 1,722 pairs (42 by 41). The correlationcoefficients of about 0.80 were not significantlyincreased by introducingdummy variablesfor neighboringversus nonneighboringcountries, Commonwealthpreference and Benelux preference.The solutionsto the CobbDouglas equations "impliesthat normal trade flow between any two countries will be proportionalto the gross national products of those countries and inversely proportionalto the distance between them."This is counter to the common belief that trade increases more than proportionately with GNP. Analysis of the deviationsfrom normal indicates that "the only group of countriesshowing a large and consistent subnormalvolume of trade are the large industrial countries."Since diversity of production was not found as highly correlated with GNP as might be expected, this implies that the large industrialcountries are the main offendersin trade restrictionism. Among these countries, France turns out to be more restrictive than average and the United States less.

JOHN W. MELLOR

Cornell University

This content downloaded on Mon, 18 Mar 2013 09:21:31 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

También podría gustarte

- InteractionDocumento4 páginasInteractionValentino ArisAún no hay calificaciones

- Ionic Conductors in Solid State DevicesDocumento20 páginasIonic Conductors in Solid State DevicesGregorio GuzmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Solomons Organic Chemistry Module IR TableDocumento1 páginaSolomons Organic Chemistry Module IR TableBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Ageing and Degradation in Microstructured Polymer Optical FiberDocumento11 páginasAgeing and Degradation in Microstructured Polymer Optical FiberBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical ApproachDocumento24 páginasInterpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical ApproachLucas TimmerAún no hay calificaciones

- Polymer BiodegradationDocumento12 páginasPolymer BiodegradationBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction to IR Spectroscopy: Key Regions and Functional Group AnalysisDocumento3 páginasIntroduction to IR Spectroscopy: Key Regions and Functional Group AnalysisBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Practical Guide For Calculating ZakatDocumento4 páginasPractical Guide For Calculating ZakatBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Electrocatalysts For Oxygen ElectrodesDocumento68 páginasElectrocatalysts For Oxygen ElectrodesBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- IR Absorption TableDocumento2 páginasIR Absorption TablefikrifazAún no hay calificaciones

- An Approach To Polymer Degradation Through MicrobesDocumento4 páginasAn Approach To Polymer Degradation Through MicrobesBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Index NotationDocumento10 páginasIndex Notationnavy12347777Aún no hay calificaciones

- What Is CivilizationDocumento1 páginaWhat Is CivilizationBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Polymer BiodegradationDocumento12 páginasPolymer BiodegradationBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- P12 (01) - Fabrication of Polymeric Scaffolds With A Controlled Distribution of PoresDocumento7 páginasP12 (01) - Fabrication of Polymeric Scaffolds With A Controlled Distribution of PoresBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Polymer ScaffoldDocumento6 páginasPolymer ScaffoldBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Pyrolysis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento9 páginasPyrolysis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Characterization of A Novel Polymeric ScaffoldDocumento9 páginasCharacterization of A Novel Polymeric ScaffoldBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Marine HydrodynamicsDocumento10 páginasMarine HydrodynamicsBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Taylor SeriesDocumento7 páginasTaylor SeriesnottherAún no hay calificaciones

- Examples of Stokes' Theorem and Gauss' Divergence TheoremDocumento6 páginasExamples of Stokes' Theorem and Gauss' Divergence TheoremBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- The Material DerivativeDocumento8 páginasThe Material DerivativeBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- The Material DerivativeDocumento8 páginasThe Material DerivativeBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Taylor Series and PolynomialsDocumento19 páginasTaylor Series and PolynomialsBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- AB2 - 5 Surfaces and Surface IntegralsDocumento17 páginasAB2 - 5 Surfaces and Surface IntegralsnooktabletAún no hay calificaciones

- Conservation of MassDocumento18 páginasConservation of MassBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Taylor SeriesDocumento7 páginasTaylor SeriesnottherAún no hay calificaciones

- DivergenceDocumento10 páginasDivergenceBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- Fluid Mechanics EquationsDocumento6 páginasFluid Mechanics EquationsratnacfdAún no hay calificaciones

- Euler's Equation For Fluid FlowDocumento6 páginasEuler's Equation For Fluid FlowBenni WewokAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- SchoolAidReductions 1Documento80 páginasSchoolAidReductions 1rkarlinAún no hay calificaciones

- Zimbabwe: Where To Now?: Tony Hawkins Graduate School of Management University of ZimbabweDocumento74 páginasZimbabwe: Where To Now?: Tony Hawkins Graduate School of Management University of ZimbabweHitesh Patni100% (1)

- Clinical Legal EducationDocumento187 páginasClinical Legal EducationAnushruti Sinha100% (1)

- Comparing Approaches to Gender Equality in DevelopmentDocumento69 páginasComparing Approaches to Gender Equality in DevelopmentMzee KodiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis On Food Security PDFDocumento8 páginasThesis On Food Security PDFbsrf4d9d100% (2)

- 2013-2013 NYS School AidDocumento86 páginas2013-2013 NYS School Aidgblock8666Aún no hay calificaciones

- Development Aid To Ethiopia: Overlooking Violence, Marginalization, and Political RepressionDocumento38 páginasDevelopment Aid To Ethiopia: Overlooking Violence, Marginalization, and Political RepressioncismercAún no hay calificaciones

- Norbert Civil EngineerDocumento16 páginasNorbert Civil EngineerAnonymous AXG1NSUvAún no hay calificaciones

- Ijssmr05 10Documento14 páginasIjssmr05 10daodu lydiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Remarks by Amb. Irwin LaRocque, ASG, Trade and Economic Integration (WTO Regional Forum On Aid For Trade For The Caribbean) (Press Release 22/2011)Documento4 páginasRemarks by Amb. Irwin LaRocque, ASG, Trade and Economic Integration (WTO Regional Forum On Aid For Trade For The Caribbean) (Press Release 22/2011)Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) Implementation Unit within the CARIFORUM DirectorateAún no hay calificaciones

- Donor MappingDocumento4 páginasDonor MappingIbrahimHatibuAún no hay calificaciones

- Motion 2014-Down BanglaDocumento286 páginasMotion 2014-Down BanglaArnold Cavalida BucoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Civil Service Reforms Often FailDocumento28 páginasWhy Civil Service Reforms Often FailDalvia EliasAún no hay calificaciones

- Environmental Policy Brief TanzaniaDocumento15 páginasEnvironmental Policy Brief Tanzaniasteven_tula4452Aún no hay calificaciones

- Human Geography Case Study BookletDocumento22 páginasHuman Geography Case Study BookletisobelhandleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Capacity DevDocumento23 páginasCapacity DevankurmanuAún no hay calificaciones

- 2004 WFP Evaluation of Afghanistan PRRO 10233Documento101 páginas2004 WFP Evaluation of Afghanistan PRRO 10233Jeffrey Marzilli100% (1)

- Hyoo Sok Kim - The Political Drivers South Korea ODA To MyanmarDocumento29 páginasHyoo Sok Kim - The Political Drivers South Korea ODA To MyanmarMuhammad FaizAún no hay calificaciones

- 1974 Genocide Plan by Henry KissingerDocumento111 páginas1974 Genocide Plan by Henry KissingerAhmed Irfan Malik83% (6)

- GF 670 Desertification Success in The SahelDocumento4 páginasGF 670 Desertification Success in The SahelTowardinho14Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Panel-QuantileDocumento36 páginasA Panel-QuantileAnonymous 4gOYyVfdfAún no hay calificaciones

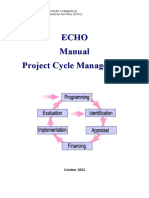

- ECHO10 - ECHO Project Cycle Management GuidelineDocumento27 páginasECHO10 - ECHO Project Cycle Management GuidelineyemaneAún no hay calificaciones

- Simon Anholt Beyond The Nation Brand The Role of Image and Identity in International RelationsDocumento7 páginasSimon Anholt Beyond The Nation Brand The Role of Image and Identity in International RelationsCristina SterbetAún no hay calificaciones

- No One Can Be Less Than Alarmed About The Ongoing Crisis in The Middle East, and The Risks To World Peace It RepresentsDocumento12 páginasNo One Can Be Less Than Alarmed About The Ongoing Crisis in The Middle East, and The Risks To World Peace It RepresentsTalha_ZakaiAún no hay calificaciones

- The Social Life of Cash Payment': Money, Markets, and The Mutualities of PovertyDocumento26 páginasThe Social Life of Cash Payment': Money, Markets, and The Mutualities of PovertyVanguar DolAún no hay calificaciones

- Project and Technical Assistance Proposals 2006-2009Documento567 páginasProject and Technical Assistance Proposals 2006-2009Nurul HandayaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Mat Clark Essay WritingDocumento150 páginasMat Clark Essay WritingadelekeyusufAún no hay calificaciones

- Annual Report 2010-2011Documento60 páginasAnnual Report 2010-2011Feinstein International CenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Escaping The Fragility TrapDocumento79 páginasEscaping The Fragility TrapJose Luis Bernal MantillaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ges 402 NotesDocumento95 páginasGes 402 NotesAzarael ZhouAún no hay calificaciones