Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Nonsense Syllables in The Music of The Ancient Greek and Byzantine Traditions

Cargado por

Davo Lo SchiavoDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Nonsense Syllables in The Music of The Ancient Greek and Byzantine Traditions

Cargado por

Davo Lo SchiavoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Nonsense Syllablesin the Musicof the Ancient Greek and ByzantineTraditions*

DIANE TOULIATOS

he origin of nonsense syllables is extremely vague. It is known from the writings of Greek philosophers and from Gnostic papyri that meaningless letters using the Greek alphabet indicated an ancient system of solmization. Several scholars have produced inconclusive evidence that the origins of meaningless letters preceded the Greek alphabet and were derived possibly from Syria or Chaldea.' This may well be. Greek letters are not unique in the composition of nonsense syllables. It is the purpose of this article to limit the examination of nonsense syllables and their function to the music of ancient Greece and Byzantium with the hope of providing some correlation between the two traditions.

231

The appearance of nonsense syllables in the music of ancient Greece and Byzantium can be traced to the use of the seven Greek vowels in gnostic music. From antiquity through the medieval are period, the vowels a, e, T],o, v, wo discussed in many historical works and treatises for their function as incantations. It is certain that these gnostic formulae were in existence long before they were documented. However, one of the first treatises to mention them is the Handbookof Harmonicsby Nichomachus of Gerasa of the second century A.D. NichoVolume 7 * Number 2 * Spring 1989 The Journal of Musicology ? 1989 by the Regents of the University of California * I am very grateful to the Center of International Studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis for providing support for this study. I would also like to thank Thomas J. Mathiesen for suggesting this topic of research. 1 Jeannin-Puyade, "L'Octoechos syrien," OriensChristianus,New Series III, 1913. For more discussion on this controversy, cf. Eric Werner, "The Psalmodic Formula Neannoe and its Origin," TheMusical QuarterlyXXVIII (1942), 96.

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY

232

machus was a Pythagorean writer who professed in this treatise that the motion of each of the seven spheres produced a sound and each of these sounds corresponded to one of the seven Ionian vowels.2 It should be pointed out that the figure "seven" was considered to be a magical number.3 In another treatise, TheElocution,Demetrius Phalereus, a contemporary of Nichomachus, documents that in Egypt the priests worshiped their gods by chanting the seven vowels which designated certain sounds or pitches and which were substituted for the performance of the aulos or kithara.4 The Greek grammarian Servius also comments on a phrase in Virgil's Aeneid,where Hecate was invoked, not by words, but by mystical sounds or incantations which have been interpreted as the seven vowels.5 Saint Irenaeus, a writer who reveals the gnostic system developed in the early Christian centuries, states in the Refutationof Heresiesthat these vowels represented the seven planets.6 Even as late as the thirteenth century, the Greek vowels were used for conjuring magic spells, but in a different context. For instance in the treatise De suffimentis (On Perfumes), the Byzantine writer Nicolas Myrepsus describes the preparation of perfume and declares that under the spell of the perfume's aroma, the preparer uttered the seven Greek vowels.7 The ancients believed that the name of each planet was expressed by one of the seven vowels. According to the order of planets, which included the sun and moon as designated by the Egyptians and Pythagorians, the vowels corresponded to the following planets: Moon, A; Mercury, E; Venus, H; Sun, I; Mars, O; Jupiter, U; and Saturn, Q. The planets and their respective vowels also represented the musical notes of the seven-stringed lyre of Orpheus.8 There were discrepancies among the ancient theoreticians as to which vowel corresponded to the tones of the lyre. The scheme of concordances shown in Table 1 is one of several schemes.9

2 exstat Karlvon Jan, ed., Musiciscriptores et veterum (1895), quidquid graecz melodiarum des pp. 276-77 and 241-42. C. E. Ruelle,"Lechantgnostico-magique septvoyellesgrecInternational Histoire la Musique d' de ques,"Congres (1900), 15. 3 F. Dornseiff, "DasAlphabetin Mystik und Magie," StotLeia, VII (1922), 33. 4 Ruelle,"Lechant gnostico-magique," 15;Egon Wellesz, History Byzantine A Mup. of vocalisicandHymnography, ed. (Oxford, 1961), pp. 65-66; H. Leclercq,"Alphabet 2nd vol. Dictionnaire et chretienne deliturgie, I, pt. i, col. 1270. d'archeologie que des gnostiques," 5 Cf. Ruelle,"Lechant gnostico-magique," 15 (ascited in Virgil's Aeneid 247). VI, p.

6 Ibid., p. 16. Also cf. Leclercq, "Alphabet vocalique," col. 1271; St. Irenaeus, Adversus LiberPrimus, C. XIV, Patrologia GraecaVII, col. 610. haereses 7 Ruelle, "Le chant gnostico-magique," p. 16. 8 Abbot Barthelemy was the first to document formally the relationship of the Greek vowels to the planets and to the sounds of the scale of the heptachord. Leclercq, "Alphabet vocalique," col. 1268 & 1272. Also, cf. F. Ring, "Zur altgriechischen Solmisationslehre," ArchivfiirMusikforschungIII (1938), 193-208. 9 It should be noted that both Nichomachus and Aristides Quintilianus deviate from this scheme. In Nichomachus' Handbook, he reverses Venus and Mercury from the

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

TABLE

Concordance of Greek Vowels to the Planets and the Tones of Orpheus' 7-Stringed Lyre

Vowels Q U

O

Planets Saturn Jupiter

Mars

GreekMusical Notes Hypate Meson Parhypate Meson

Lichanos Meson

Pitch e f

g

I H E A

Sun Venus Mercury Moon

Mese Trite Synemmenon Paranete Synemmenon Nete Synemmenon

a b-flat c d

From this table it can be seen that the ambitus of the gnostic formula is from the Greek note Hypate Meson, which is the equivalent of an e, to the Nete Synemmenon, which is the d above. With the correlation of vowels to Greek musical notes of the heptachord, a new musical system of notation was designated. Regardless for whom or for what the vowels were chanted, the gnostic formulae functioned as invocations and were always chanted in a nonsensical manner. Found in both amulets and magic papyri, the formulae appeared in a variety of arrangements, including anagrams, retrogrades, and most often repeated-note groupings. In explaining the frequent repetition of notes in the gnostic formulae, the scholar Elie Poiree indicates "that these notes had a rapid movement that corresponded to a sort of trembling of the voice, a figure probably called a teretism."10 The term teretism is defined by an anonymous Hellenistic author of a

treatise On Music (published by A.-J.-H. Vincent) as a multiple of the

233

scheme of Table i and Aristides in his treatise On Music differs on both planets and vowels in five of the seven cases. In other instances, eight rather than seven notes were correlated with planets. This leads to the issue of the octochord versus the ancient heptachord. The scheme of Table 1 was adopted from Kopp. Cf. U. Kopp, Palaeographia critica III (Mannheim, 1829), 304 and 334-35. For the relation of the vowels to the planets, cf. Fredericus Bellermann, Anonymiscriptiode musica(Berlin, 1841), p. 89; A.-J.-H. Vincent, sur Reponsea M. Fetis et refutationde son memoire cettequestion:Les Grecset les Romains ont-ils connu I' harmoniesimultaneedessons (Lille, 1859); Ruelle, "Le chant gnostico-magique," p. 21; Leclercq, "Alphabet vocalique," col. 1281. For turther discussion of this problem of concordances, cf. Thomas J. Mathiesen, trans., AristidesQuintilianus on Music in Three and Books:Introduction,Commentary Annotations(New Haven, 1983), pp. 48-49. 1o Elie Poiree, "Chant des sept voyelles: Analyse musicale," CongresInternationald' Histoirede la Musique (19 1), p. 31.

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY of a Gnostic Formula.

a

77 171

EXAMPLE

1. Transcription

00000

-Tb

a e

T jIrr'JJ r

e ?7

717 7 tt t 0 0 0 0

JJJJ

V V V V u V V 0

J

w O c Wo

234

same sound so that it appears to be a type of trill." A gnostic formula exhibiting the teretism effect is found in Example i. This musical example is transcribed according to the specified tone of the heptachord appropriated to each vowel. Up to this point, discussion in this paper has focused on the use of vowels. It is uncertain when a consonant was added to these vowels to make them nonsense syllables. Of the several ancient Greek theoretical treatises in existence, the treatise AboutMusic by Aristides Quintilianus (written sometime between the first and fourth centuries A.D.)12and the treatise known as Bellermann's Anonymous(of uncertain date) incorporate discussions on these vowels joined to consonants. In the treatise of Aristides Quintilianus, the elements of creation, the planetary movements, the signs of the zodiac, as well as Greek musical notes, are all designated by the Greek vowels. The vowels are characterized by gender: some being masculine; some, feminine; and others medial, that is, a mixture of the two. Aristides Quintilianus states that the gender of notes is derived from the gender of the vowels. This also applies to the gender of intervals and scale tones. 3 Although all seven vowels are discussed, Aristides Quintilianus considers only four to be appropriately associated to the notes of the tetrachords and consequently used in a system of solmization. These vowels were specifically selected for the vocal qualities that each would emit and for the effect that they would produce on

l A.-J.-H. Vincent, "Notices sur trois manuscrits grecs relatif a la musique," Notices et extraitsdes manuscritsde la Bibliothequedu Roi, XVI, 2nd part (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1847), 53, 223. Also cf. Leclercq, "Alphabet vocalique," col. 1284. 12 ThomasJ. Mathiesen, trans., AristidesQuintilianuson Music in ThreeBooks,p. 1o. This date is also substantiated by R. P. Winnington-Ingram, "Aristides Quintilianus," The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 2nd ed. by N. G. L. Hammond and H. H. Scullard (Oxford, 1970), p. ill. '3 For a more detailed and thorough discussion of gender, vowels, planets, etc., cf. Mathiesen, AristidesQuintilianus, p. 33.

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

the listener. The four vowels isolated for solmization are alpha, epsilon, eta, and omega. He respectively designates them according to gender as medial (with more masculine tendencies), medial (with more feminine tendencies), feminine, and masculine.14 Aristides Quintilianus' reason for excluding the remaining vowels from association with the tones of the tetrachords is that he considered them to be too thin in their production of sound and consequently not strong enough for the purpose of

solmization.15

After designating the four vowels most suited for solmization of the tones of the Greater and Lesser Perfect Systems, Aristides Quintilianus indicates that these vowels should not stand alone because of their gaping sound.16 To counteract this, he proposes that a consonant be juxtaposed to the vowel. The most appropriate consonant was the tau: "the most beautiful of the consonants."'7 He considered the tau to be the most perfect prepositive letter and supports this claim with the fact that in almost all the definite articles of the Greek language the tau precedes the vowels.18 He also equates the sound of the tau to a stringedinstrument as indicated in the following description: .... it [the tau] alone makes a sound answeringto the stringsof the instruments,and its sound is the smoothest.It is neither made harsh by a certain breathing, like the rough mutes; nor does it allow the tongue to be motionless,like each of the other two smoothmutes;nor does it ignobly and boorishly emit a hissing, like the double consonantsand the independent sigma;nor is it thin and weak,like the liquids.'9 Aristides Quintilianus compares the marriage of tau to the four vowels with the unity of the elements of creation. The vowel epsilon was symbolic of earth; alpha represented water; eta, air; and omega, fire. The letter tau was combined with these vowels and represented ether, "for its form is akin to the plectrum and it is sacred to god, who, a phrase of the wiser men declares, is the plectrum of universe. Therefore, it has been combined with all the vowels corresponding to the notes,just as the ether accords living power to the other elements. Therefore, a cosmos of matter is the motion of the elements, while a cosmos of the soul is the melody of the vowels."20With the selection of the consonant tau preceding the vowels for the purpose of articulation, the syllables ta, Te, TNl,and

'4 Ibid. 5 Ibid., p. 142. i6 Ibid., p. 143. '7 Ibid.

18

20

235

Ibid. The various forms of the Greek definite article are TOi, TO,ITv, Tig, TI, etc. Ibid., p. 201.

'9 Ibid.

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY

TABLE 2 The System of Solmization in the Greater Perfect and Lesser Perfect Systems

Greek Name Proslambanomenos Hypate Hypaton Parhypate Hypaton Lichanos Hypaton Hypate Meson Parhypate Meson Lichanos Meson Mese Mese Trite Synemmenon Paranete Synemmenon Nete Synemmenon Paramese 236

__23

Pitch A B

c

Tetrachord

Syllable

TE, Hypaton

TO)) T1)

d

e

f g

a a

Ta)

Meson Te)

etO)

b-flat

c

Synemmenon (used in Lesser Perfect)

d b c d J e' f'

g'

)

Ol)

Trite Diezeugmenon Paranete Diezeugmenon Nete Diezeugmenon Trite Hyperbolaion Paranete Hyperbolaion Nete Hyperbolaion Nete Hyperbolaion whole-tones= )

T?-Tea

Diezeugmenon

To)

Tt

Hyperbolaion

TO)

a'

semitones = ) Ta-Tl

T1)

TO)-TCa

TCO-TE

To were assigned to different pitches of the tetrachords and were used in the practice of solmization in ancient Greek music. Table 2 outlines

this system of solmization and shows the order of syllables corresponding to the scale of Greek tones and the intervallic relationships of whole tones and semitones with the scale.21

21 In this solmization system the order began with the syllable "TE"and followed with the repeating sequence: xa, Ti, TO. The exception to this was the note Mese in the Meson tetrachord that was sung to the syllable TE.Cf. Mathiesen, ibid., p. 144.

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

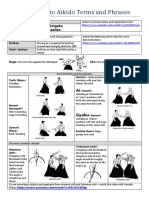

In the treatise from antiquity known as Bellermann's Anonymous, the Greek solmization system is included with few differences from those presented in Aristides Quintilianus. It should be especially noted that in Bellermann's Anonyfnous these same vowels preceded by the tau are employed for singing intervals. Example 2a displays how the syllables were used in the solfege of a repeated-note slurred scale.22In this scale the tau is sung only on the first note of the slur and is not repeated on the second note, so that the vowel sound of the first pitch elides with the second. Example 2b shows that this same solmization system applies to the solfege of intervals.23The treatise also reveals that these nonsense syllables functioned as a means of articulation. To this end three methods or groups of articulation were created: kompismos, melismos, and teretismos.24As demonstrated in Example 2c, all three types of articulations were formed by the letter tau producing a dental consonant which always preceded the vowel and by the letter nu producing a nasal liquid consonant which could precede or succeed the vowel. An ornament applied to instrumental music, the kompismos was an emphasis or accent on the first of a repeated note and was articulated as "TcOv TO."More suitable to vocal music, the melismos was a detached articulation of a revw." The combination of these two peated note and was chanted "T(Ov articulations on a repeated note was called the teretismos.25 Between the period of antiquity and the fourteenth century, there is a gap in the theoretical treatises which mention vocalisations set to these same meaningless syllables. It is not until the Byzantine theoretician Manuel Bryennius that these syllables are discussed. Bryennius in his treatise, the Harmonicswritten about 1300, draws heavily on Aristides Quintilianus.26 The affinities between the two treatises are so plentiful that there is no doubt that Bryennius adapts much of his information on nonsense syllables from Aristides Quintilianus and provides a bridge in their usage between antiquity and the Byzantine tradition where they reappear. Although much of the information on the syllables and their

22 Bellermann, Anonymiscriptio,p. 23. Also, cf. Dietmar Najock's more comprehensive modern edition entitled Drei anonymegriechischeTraktateiiberdie Musik: Ein Kommentierte Arbeiten,Band 2 Anonymus,GittingerMusikwissenschaftliche NeuausgabedesBellermannschen (1972). 23 Ibid. Also, Ruelle, "La Solmisation chez les anciens Grecs," Sammelbdnde Internader tionalenMusikgesellschaft (1907-08), 520. IX 24 Bellermann, Anonymiscriptio, pp. 25-26. Najock, Drei anonyme, p. 187. G. Lange, "Zur Geschichte der Solmisation," Sammelbiindeder Internationalen MusikgesellschaftI 25 Bellermann, Anonymiscriptio, pp. 25-26. Bellermann makes use of the Bryennius treatise in his textual edition of Anonymiscriptiode musica.G. H.Jonker, ed. TheHarmonics of Manuel Bryennius(Groningen, 1970), pp. 311-13. Najock, Drei anonyme,p. 174. 26 ThomasJ. Mathiesen, "Aristides Quintilianus and the Harmonics of Manuel Bryennius: A Study in Byzantine Music Theory,"Journal of Music TheoryXXVII/1 (1983), 31-

237

(1900), 535.

47.

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY

EXAMPLE 2. System of Solmization

Presented in Bellermann's Anonymous; a) for the repeated-note slurred scale; b) for intervals; c) for the three groups of articulation.

a)

Tea ra7

r

1 r7c

r rr

rwca rTa

rfr

TTw

r

rwe

b)

3rd: Two 4th: rww 5th: Twe

Kompismos

c)

6 '_

TMw Melismos

J

TWi

'I

Tav

J

Ta

238

T :VJ J

T?V VO Teretismos

IJ.J

TraV

I

pa

TWV

TWV

VW

Ta

TaV

va

articulations is identical, Bryennius' interpretation worthy of mention:

of the teretismos is

Teretismos is used in reference to both [instrumental and vocal music], namely when a person, in singing a melody plucks the strings at the same time with his fingers or with a plectrum in accordance with the melody; strictly speaking, however, this last term must be reserved for the case when a person, in singing and playing the instrument at the same time, traverses not only the upper part of the musical scale, i.e. the Neton tetrachord, but also the lower part, i.e. the Hypaton tetrachord, for this is what the cicada distinctly appears to

do.27

27

Jonker, ed. The Harmonics,p. 313.

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

It is of significance in this passage that the teretismos is described as a musical sound that compares to the warbling or trilling sounds produced by the cicada. In the Byzantine tradition these nonsense syllables reappear in the Kalophonic or Beautified style of Byzantine chant and are called teretismata-an obvious derivation from teretismos, the term described so explicitly by Bryennius. The Kalophonic style is a new melodic style of the fourteenth century that was extravagantly embellished and extremely melismatic.28 This differs from the earlier simple, syllabic style of chant that was based on traditional formulaic principles. The work of identifiable composers, these new kalophonic chants developed a characteristic idiom: freely composed melismas chanted to meaningless syllables known as teretismata. These newly composed chants more commonly expanded traditional forms with the interpolation of teretismata. Used for vocal effects in melismatic sections, the teretismata displayed a type of coloratura style of chanting with rapid, repeated single-note articulations and wide leaps. In the Kalophonic style the teretismata were meaningless syllables beginning with either the consonants tau (T)or rho (Q)and followed by a

vowel: TE, QE,Q?, TO,QO,Qo, TL,QL,Qi etc.29 The rhapsodic melodies of the 239

teretismata were most often found in the concluding sections of the Akolouthia manuscripts that were known as Kratemata and/or Anagrammatismoi and were usually arranged according to modes. The title "Kratemata"is derived from the function of these nonsense syllables in Byzantine chant: that is, to prolong or "xQatt)" the melody from moving. The title "Anagrammatismoi" signifies that to the Byzantines these vocalisations were "agrammatoi" or senseless. As Kratemata the teretismata were most often found as independent musical selections; as Anagrammatismoi they could be interpolated into liturgical chants, especially the stichera or verses for a feast.3o Besides the teretismata, which begin with the consonants tau or rho, there were other meaningless syllables and letters found in the Kalophonic chants: such as, X, ou, Used interyy, 2 and u (non-alphabetical letters sounded as an "n").31

Kenneth Levy, "A Hymn for Thursday in Holy Week,"Journal of theAmericanMusicologicalSocietyXVI (Summer, 1963), 155-56. Dimitri Conomos, ByzantineTrisagia and Cheroubika theFourteenthand FifteenthCenturies(Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for of Chantof the Patristic Studies, 1974), p. 45. Diane Touliatos-Banker, TheByzantineAmomos Fourteenand Fifteenth Centuries(Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1985), pp. 37-39 and 173. K. Levy, "Byzantine rite, music of the," TheNew GroveII, 559. 29 Buvavttvfc For information on the teretismata, cf. Grigoris Stathis, Ta XLQ6oyQacac Mouotxfjc. "Aytov 'Oog, I (Athens, 1975), IX';E. G. Vamvoudakis, "Ta ev Ti BvItavxtvf X (1933), 353-61. uovotxf] 'xQaxtiYatTa'," 'ETetiQLi 'EuatleiCa BUvavttvivCov6bv 30 Conomos, ByzantineTrisagia, p. 274. 31 Levy states that these meaningless letters were first found in the Asmatikon manuscripts. Cf. K. Levy, "The Byzantine Communion Cycle and its Slavic Counterpart, "Actes du XIIeCongresInternationald' EtudesByzantines,Ochride196i II (Belgrade, 1963), 573.

28

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY

240

changeably, these non-alphabetical letters were also used in the solmization of the enechemata or intonation formulae.32 These letters functioned similarly to the teretismata in that they prolonged the melody or separated words or phrases. Interpolated sections with these nonsense syllables occurred in many of the liturgical texts of Byzantine chants of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries and even the neo-Byzantine era. It was in these interpolations with nonsense syllables that composers had the freedom to concentrate on the musical style of the chant and not the relationship of melody to text. Dimitri Conomos' explanation as to why such a large amount of embellished material was inserted in settings of liturgical texts is that "chanters freely included or omitted such additions according to the time allowed by the type and nature of the service."33 It was one thing to have nonsense letters included in the magic papyri and in the pagan rituals of antiquity but how could their presence be explained in Byzantine liturgical chant? From the commentaries written by the church fathers, as well as scriptural references, nonsense utterances in liturgical chant were accepted as the Christian concept of glossolalia or the Pentecostal experience of speaking in tongues.34 Furthermore, the patristic expositions explain glossolalia as "wordlessjubilation" by humans who were attempting to imitate the singing of angels.35 This hypothesis is also supported in the Exegesisof Gerasimos, a mid-seventeenth century monk of Crete: The origin of the 'terere'is to be found with the prophetswho heard from heaven the sound of much water,whichis a sound, not a word. Similarly,the angels chant with wordlesssounds as St. Paul relatesin his descriptionof the third heaven.36 Although the teretismata are "wordless sounds," in his Exegesis Gerasimos attempts to give them a specific purpose through symbolism. The teretismata represent the Trinity by means of the letter tau which in the Byzantine system of numbering is equivalent to 300, representing

" 32 Conomos claims that the letter " , " preceded the vowel epsilon and the letter 2" was used before alpha, omikron or omega. Conomos, ByzantineTrisagia, p. 263. 33 Ibid., p. 286. 34 St. Ieronymos, In PsalmumXXXII, Patrologia Latina XXVI, col. 970; St. Augustine, In PsalmumXXXII, Patrologia Latina XXXVI, col. 283; Acts 10:46, 9:6; I Corinthians 12:30, 14:13. 35 Ibid. Also, see Conomos' ByzantineTrisagia, p. 273. E. Werner claims this was a Hebraic concept documented in the Palestinian Midrashic texts. Cf. E. Werner, The Sacred Bridge (London and New York, 1959), p. 168. 36 Gerasimos' Exegesis is in nav6extn I 'ExxoTiac IV (Conl toi XQL0oTo eya&kzX stantinople, 1851), 885-91. The translation is found in Conomos' ByzantineTrisagia, p. 275-

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. The letter rho stands for the source which is God the Father. The joining of the vowel, epsior root (QiLcx), lon, with either of these consonants was the creation of divine melody.37 With a reference obviously taken from Aristides Quintilianus, Gerasimos states that the teretismata represented the plucking of a stringed instrument. Therefore, they were used as a substitute to the soulless instruments which were used by the ancient Greeks who worshiped soulless gods. Lastly, Gerasimos compares the teretismata to the birds in heaven and the cicadas of nature-the latter, a reference from Manuel Bryennius. Through this symbolism Gerasimos tries to prove that teretismata were not accidently used in liturgical chant, but were there for the purpose of glorifying God.38 In Gerasimos' Exegesisthere are several references comparing the teretismata to the singing of birds, the trilling of cicadas, and the running of rivers. These references to nature often appear in the descriptive titles of Kratemata: such as, oTa&rttL (river) and &16bov(nightinThe descriptive titles are not limited to the sounds of nature but gale).39

include musical instruments, such as tQovUtEta (trumpet), ohlzavTQov

(bells in a wooden frame used in monasteries), and xauiLava (a bell) and even descriptive occasions, such as roXECLxCOv (warlike). These evocative titles were intended to convey a sense of aural imagery in the listener. Example 3 is a transcription of a Kratema entitled "A Bell" from Athens MS. 2406, folio i8r, which was written in 1453, the fall of the Byzantine empire. From the rubric on the preceding folio, it is indicated that the bo0Ettx6g) and that composer is Gregoritze domestikos (FrQyoQitrTl this Kratema was to be chanted within the palace for the current emperor who was Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor.40 In this Kratema the nonsense syllables articulate repeated single-notes and a recurring interval of a fifth so that these vocalisations imitate the chiming of a bell. The function of the nonsense syllables in this mid-fifteenth century example, therefore, is no different from those in antiquity. In both traditions the nonsense syllables served as a substitute for instrumental music.

241

Present in the Hellenistic and Byzantine eras, nonsense syllables-vowels preceded by consonants-were used for aes37 38

39

Conomos,Byzantine Trisagia, 275-76. pp. Ibid., pp. 276-77.

(Vienna, 1913),cited by Werner,TheSacredBridge, 167. p. 40 Athens MS.2406, folio 6o[E'oTLXO. jOiYlq0lV n'ToitlRa, rQTlyogitlTo 17v: "T6xazO6v 'Oi

tcXOnv, JctQa alToU. xaci

der Ibid., p. 278. Cf. R. Lach, Beitrige zurEntwicklungsgeschichte ornamentalen Melopiie EvTO() taXactiL 'o'LilLc Tov PalditE.ou UT6TExatLov i'UoTO tO

xax)o oTEQVTg ...."

THE

JOURNAL

OF MUSICOLOGY

EXAMPLE3. A Kratema Entitled "A Bell" by Gregoritze Domestikos.

Mode IV Authentic Athens MS. 2406, folio 13r

r XoL r

70

r

p7ZTO 71 p7 po

pl

u r r 6 r JL

p po pO

eroy 7v

TYe Te

77e

pe

rou

rLJ~ rv~r #T*J

r7 p PLpt pt

pt pt

p

JI

e pe

-4 J

pe pe pe

$

e e ?a e pe re

'^ riV r3^?^

pp

-r

e a

TOV pe e

r

?e

rF

e p pe

'f 6 r

pe o po

Poe p

r re

VV

e pe p

po

rt Pt P

Pi

7T70 7TL 7T0 7Ti 77?Tt

pt pi

po P

t T7 -

7TO

242

?77- -

r

270

r I

?7T ?70

7Tt

I

770 7

I

?t77 7 p Pp po 7Ti 770

7 ?7TO 7r

ri

7Tt A

r 5 F 6 ?6 L-r-6

P pp p

>

i

pp P p7 p Pt

> I

pp

p

>

pe

>

pe

TO

>

7TO

7 TO

T7e e

pe

pe

P pC pe

pe PC

pe

pe

pae

pe pe

pe

pue

pe

pe

pe

pue

Te 7TeC 7TTC

TCe

e pe

pe

I\

pe

re

pe

pe

pe

pe

Te

ppe

?re 2re

?7T

-e -e

Xe -

C -

rue

re

re

ppe

pe

pe:

NONSENSE

SYLLABLES

thetic reasons. The consonant erased the gaping sound of a prolonged vowel. Although more meaningless letters were found in the Byzantine tradition, the most common syllable in both eras was a Greek vowel preceded by a tau. By giving the singer a means of articulating with the emphasis of a consonant, an instrumental sound could be achieved vocally. In antiquity the gnostic vowels and nonsense syllables were associated with specific musical notes. In the Byzantine tradition this was not the case. These syllables were not attached to any specific pitch nor were the interpolations of these syllables in musical phrases consistent. In Byzantium the unrestricted freedom of insertion and of attaching a syllable to a pitch was left to the discretion of the composer. What was common to both traditions was that these syllables articulated a teretism, a type of melodic ornament, and that they emitted vocal qualities which produced an effect on the listener. It is not accidental that this solmization practice was found in both traditions but is evidence of Greek theory influencing Byzantine theory and practice.41 This ancient system of solmization not only influenced the Byzantine tradition but also provided a link to the mnemonic solmization practices which developed in the West, for it is probably from similar syllables that the noeane formulae of Western medieval theory were derived.42 University Missouri-St.Louis of

41 Other evidence of Greek theory influencing Byzantine theory may be found in C. H0eg, "La Th6orie de la musique byzantine," Revue des etudesgrecquesXXXV/1 12, 321. 42 This presents another perplexing problem that deserves attention in another study. Cf. Werner, "The Psalmodic Formula Neannoe and its Origins," The Musical Quarterly XXVIII (1942), 93-99.

243

También podría gustarte

- 2012 Madama Butterfly ProgramDocumento80 páginas2012 Madama Butterfly ProgramLyric Opera of Kansas CityAún no hay calificaciones

- Lied Romántico, GroveDocumento22 páginasLied Romántico, GroveOrlando MorenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Arnold, Solo Mottett in VeniceDocumento14 páginasArnold, Solo Mottett in VeniceEgidio Pozzi100% (1)

- Henry Purcell - Dido's Lament From Dido and Aeneas - A Piece A WeekDocumento3 páginasHenry Purcell - Dido's Lament From Dido and Aeneas - A Piece A WeekjanelleiversAún no hay calificaciones

- Finley Drake Program 4.25.18 PDFDocumento40 páginasFinley Drake Program 4.25.18 PDFAnonymous mHXywXAún no hay calificaciones

- Klein BelCanto 1924Documento5 páginasKlein BelCanto 1924Y XiaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Alexim - From Reflection To CompanionDocumento17 páginasAlexim - From Reflection To CompanionVicente AleximAún no hay calificaciones

- Don Pasquale BilingüeDocumento47 páginasDon Pasquale Bilingüemadamina5812Aún no hay calificaciones

- Schoenberg - A New Twelve-Tone NotationDocumento9 páginasSchoenberg - A New Twelve-Tone NotationCharles K. NeimogAún no hay calificaciones

- Class Notes - Baroque Opera PowerpointDocumento9 páginasClass Notes - Baroque Opera PowerpointlinkycatAún no hay calificaciones

- Analysis Phenomenology SpectralDocumento21 páginasAnalysis Phenomenology SpectralbeniaminAún no hay calificaciones

- The Castrato Meets The CyborgDocumento30 páginasThe Castrato Meets The CyborgStella Ofis AtzemiAún no hay calificaciones

- Source 04Documento118 páginasSource 04Ezequiel Eduardo100% (1)

- The Effect of Mediated Music Lessons On The Development of At-Risk Elementary School ChildrenDocumento5 páginasThe Effect of Mediated Music Lessons On The Development of At-Risk Elementary School ChildrenKarina LópezAún no hay calificaciones

- Greek Music Ancient History EncyclopediaDocumento7 páginasGreek Music Ancient History EncyclopediaSergio Miguel MiguelAún no hay calificaciones

- Dance NotationDocumento1 páginaDance NotationDenise PagcaliwaganAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Animals in Western MusicDocumento19 páginasHistory of Animals in Western MusicSIPBarroso100% (1)

- Henry Purcell Music and LettersDocumento8 páginasHenry Purcell Music and LettersDaniel SananikoneAún no hay calificaciones

- Historically Informed PerformanceDocumento13 páginasHistorically Informed Performanceguitar_theoryAún no hay calificaciones

- K366 Idomeneo For PDFDocumento63 páginasK366 Idomeneo For PDFGerard Pablo0% (1)

- Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and EgyptDocumento19 páginasMusic in Ancient Mesopotamia and EgyptDiego MiliaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Dramatization of Hypermetric Conflicts in Beethoven's 9th Symphony's Scherzo - Richard Cohn (1991)Documento20 páginasThe Dramatization of Hypermetric Conflicts in Beethoven's 9th Symphony's Scherzo - Richard Cohn (1991)alsebalAún no hay calificaciones

- Procurans OdiumDocumento13 páginasProcurans OdiumErhan SavasAún no hay calificaciones

- Eero Tarasti - The Emancipation of The Sign On The Corporeal and Gestural Meanings in Music PDFDocumento12 páginasEero Tarasti - The Emancipation of The Sign On The Corporeal and Gestural Meanings in Music PDFYuriPiresAún no hay calificaciones

- Fanny Hensel The Other MendelssohnDocumento455 páginasFanny Hensel The Other Mendelssohnacontratiempo100% (1)

- Hepokoski (2001-02) Back and Forth From Egmont - Beethoven, Mozart, andDocumento29 páginasHepokoski (2001-02) Back and Forth From Egmont - Beethoven, Mozart, andIma BageAún no hay calificaciones

- Caldara & Zelenka - Missa ProvidentiaeDocumento104 páginasCaldara & Zelenka - Missa ProvidentiaeTim FierensAún no hay calificaciones

- German Opera WagnerDocumento31 páginasGerman Opera WagnerRui GilAún no hay calificaciones

- Czajkowski AML Music PHD 2018Documento528 páginasCzajkowski AML Music PHD 2018Estevan KühnAún no hay calificaciones

- Gurrelieder 1Documento1 páginaGurrelieder 1fiesta2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Secular Song of The Spanish ReDocumento177 páginasSecular Song of The Spanish ReYusuf100% (1)

- A Guide For The Teaching of Vocal Technique in The High School CHDocumento66 páginasA Guide For The Teaching of Vocal Technique in The High School CHNavyaAún no hay calificaciones

- BLACKBURN A Lost Guide To Tinctoris's TeachingsDocumento45 páginasBLACKBURN A Lost Guide To Tinctoris's TeachingsDomen MarincicAún no hay calificaciones

- Oxford University Press The Musical QuarterlyDocumento19 páginasOxford University Press The Musical Quarterlybennyho1216100% (1)

- Why Are There No Great Female ComposersDocumento4 páginasWhy Are There No Great Female Composersbrucebruce888Aún no hay calificaciones

- History and Performance Practices-BotsteinDocumento6 páginasHistory and Performance Practices-BotsteinSuzana AmorimAún no hay calificaciones

- Strauss' Salome - Tasteless?Documento7 páginasStrauss' Salome - Tasteless?Kai WikeleyAún no hay calificaciones

- University of California Press American Musicological SocietyDocumento5 páginasUniversity of California Press American Musicological SocietyMaria NavarroAún no hay calificaciones

- Women Composer in ByzantiumDocumento10 páginasWomen Composer in ByzantiumDaniel Mocanu100% (1)

- Conrad - Von - Zabern-De Modo Bene Cantandi PDFDocumento13 páginasConrad - Von - Zabern-De Modo Bene Cantandi PDFSandrah Silvio100% (1)

- Weebly CVDocumento4 páginasWeebly CVapi-159952516Aún no hay calificaciones

- Review of Schumann's Dichterliebe and EarlyDocumento13 páginasReview of Schumann's Dichterliebe and Earlybosendorfer240% (1)

- 19.yy Opera Analiz Kitabı İNGDocumento259 páginas19.yy Opera Analiz Kitabı İNGAykut Şerbetcioğlu100% (1)

- 6 Opera and Modes of Theatrical Production: Simon WilliamsDocumento20 páginas6 Opera and Modes of Theatrical Production: Simon WilliamsJilly CookeAún no hay calificaciones

- The Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel: The Science and Aesthetics of An Eighteenth-Century Cause CélèbreDocumento63 páginasThe Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel: The Science and Aesthetics of An Eighteenth-Century Cause CélèbretheatreoftheblindAún no hay calificaciones

- Kahn 1995Documento4 páginasKahn 1995Daniel Dos SantosAún no hay calificaciones

- This Content Downloaded From 158.135.171.167 On Mon, 20 Sep 2021 18:55:01 UTCDocumento19 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 158.135.171.167 On Mon, 20 Sep 2021 18:55:01 UTCSamuel de Souza100% (1)

- "Orchestral Performance Practices in The Nineteenth Century: Size, Proportions, and Seating," by Daniel J. KouryDocumento4 páginas"Orchestral Performance Practices in The Nineteenth Century: Size, Proportions, and Seating," by Daniel J. KouryWongHeiChitAún no hay calificaciones

- Terrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiDe EverandTerrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiAún no hay calificaciones

- Early Music - V31nº2 - MAYO - 2003Documento160 páginasEarly Music - V31nº2 - MAYO - 2003Au Rora100% (1)

- Saint-Saens Organ SymphonyDocumento2 páginasSaint-Saens Organ SymphonyMatthew LynchAún no hay calificaciones

- Vertical Thoughts - Feldman, Judaism, and The Open Aesthetic - Contemporary Music Review - Vol 32, No 6Documento3 páginasVertical Thoughts - Feldman, Judaism, and The Open Aesthetic - Contemporary Music Review - Vol 32, No 6P ZAún no hay calificaciones

- MICHELLE DUNCAN The Operatic Scandal of The Singing Body - Voice, Presence, PerformativityDocumento25 páginasMICHELLE DUNCAN The Operatic Scandal of The Singing Body - Voice, Presence, PerformativityGarrison GerardAún no hay calificaciones

- Whitney Museum: Meredith Monk Music BrochureDocumento3 páginasWhitney Museum: Meredith Monk Music Brochurewhitneymuseum100% (2)

- Damigella Tutta Bella TraducidaDocumento1 páginaDamigella Tutta Bella TraducidaJuan CasasbellasAún no hay calificaciones

- Acting and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated ChecklistDocumento12 páginasActing and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated Checklistvictorz8200Aún no hay calificaciones

- Bohemian Rhapsody Pentatonix Bohemian RhapsodyDocumento23 páginasBohemian Rhapsody Pentatonix Bohemian RhapsodyAaron Sharma-SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Aeschylus' AmymoneDocumento10 páginasAeschylus' AmymoneDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Classical TraditionDocumento8 páginasThe Classical TraditionDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Crisis of The Third Century As Seen by ContemporariesDocumento23 páginasCrisis of The Third Century As Seen by ContemporariesDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Composition of Photius' BibliothecaDocumento5 páginasComposition of Photius' BibliothecaDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Social Structure and Relations in Fourteenth Century ByzantiumDocumento488 páginasSocial Structure and Relations in Fourteenth Century ByzantiumDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- The Suda's Life of SophoclesDocumento189 páginasThe Suda's Life of SophoclesDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Byzantine Legal Culture Under The Macedonian Dynasty, 867-1056Documento252 páginasByzantine Legal Culture Under The Macedonian Dynasty, 867-1056Davo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Post-Byzantine Armenian BookbindingDocumento14 páginasPost-Byzantine Armenian BookbindingDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Οι Δρόμοι Της ΓνώσηςDocumento21 páginasΟι Δρόμοι Της ΓνώσηςDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Showing Praise in Greek Choral Lyric and BeyondDocumento30 páginasShowing Praise in Greek Choral Lyric and BeyondDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Musiques Et Danses Dans L'antiquitéDocumento5 páginasMusiques Et Danses Dans L'antiquitéDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Dualist Heresy in Aquitaine and The Agenais, c.1000-c.1249Documento317 páginasDualist Heresy in Aquitaine and The Agenais, c.1000-c.1249Davo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Note Sulla Fenomenologia Del Movimento in Maurice Merleau-PontyDocumento22 páginasNote Sulla Fenomenologia Del Movimento in Maurice Merleau-PontyDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Digenes Akrites. New Approaches To Byzantine Heroic PoetryDocumento8 páginasDigenes Akrites. New Approaches To Byzantine Heroic PoetryDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Il Teatro Significa Vivere Sul Serio Quello Che Gli Altri Nella Vita Recitano MaleDocumento284 páginasIl Teatro Significa Vivere Sul Serio Quello Che Gli Altri Nella Vita Recitano MaleDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Plato and Aristotle Mimesis, Catharsis, and The Functions of ArtDocumento15 páginasPlato and Aristotle Mimesis, Catharsis, and The Functions of ArtVictor Hugo MontoyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Aristippus and Freedom - Kristian Urstad PDFDocumento15 páginasAristippus and Freedom - Kristian Urstad PDFDavo Lo SchiavoAún no hay calificaciones

- Summa Theologica - Saint Thomas AquinasDocumento4201 páginasSumma Theologica - Saint Thomas AquinasDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- Zizek - Pervert's Guide To Ideology - PresskitDocumento30 páginasZizek - Pervert's Guide To Ideology - PresskitDavo Lo Schiavo100% (6)

- Dying Light Patch 1 4 nosTEAMDying Light Patch 1 4 nosTEAM PDFDocumento4 páginasDying Light Patch 1 4 nosTEAMDying Light Patch 1 4 nosTEAM PDFLeonAún no hay calificaciones

- A.I (Alien Invasion) Guard: Android-Based Tower Defense GameDocumento16 páginasA.I (Alien Invasion) Guard: Android-Based Tower Defense GameMeyoor OneacAún no hay calificaciones

- Job Masonry A Half Brick Wall Using A Stretcher BondDocumento7 páginasJob Masonry A Half Brick Wall Using A Stretcher BondNovia RaninosiAún no hay calificaciones

- Abrasive Selection Guide - AGSCODocumento1 páginaAbrasive Selection Guide - AGSCOYoutube For EducationAún no hay calificaciones

- Sienna Mynx-Black Butterfly - SexChecksFinalDocumento9 páginasSienna Mynx-Black Butterfly - SexChecksFinalLaura Rosales100% (2)

- Thagamae Unnathan LyricsDocumento1 páginaThagamae Unnathan LyricsGokul ShanmuganAún no hay calificaciones

- JessesIceCreamStand3 5Documento5 páginasJessesIceCreamStand3 5yoAún no hay calificaciones

- Fingerstyle Guitar - Fingerpicking Patterns and ExercisesDocumento42 páginasFingerstyle Guitar - Fingerpicking Patterns and ExercisesSeminario Lipa100% (6)

- Magic Medicine A Trip Through The Intoxicating History and Modernday Use of Psychedelic Plants and SubstancesDocumento3 páginasMagic Medicine A Trip Through The Intoxicating History and Modernday Use of Psychedelic Plants and SubstancesGenesis Manoj0% (2)

- Cambridge O Level: English Language 1123/22Documento8 páginasCambridge O Level: English Language 1123/22Shoaib KaziAún no hay calificaciones

- AJP - Questions Pract 04Documento1 páginaAJP - Questions Pract 04api-3728136Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Railway ChildrenDocumento3 páginasThe Railway ChildrenElen Marlina0% (1)

- Jaearmntk PDFDocumento272 páginasJaearmntk PDFMalavika SivagurunathanAún no hay calificaciones

- Chodkiewicz Seal of The Saints Fons VitaeDocumento3 páginasChodkiewicz Seal of The Saints Fons VitaeashfaqamarAún no hay calificaciones

- A Short Guide To Aikido Terms and Phrases PDFDocumento2 páginasA Short Guide To Aikido Terms and Phrases PDFProud to be Pinoy (Devs)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fill in The GapsDocumento4 páginasFill in The GapsRajeev NiraulaAún no hay calificaciones

- Annotated Bibliography 2Documento6 páginasAnnotated Bibliography 2api-252394912Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fahrenheit 451 One Pager Project Directions RubricDocumento2 páginasFahrenheit 451 One Pager Project Directions Rubricapi-553323766Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fearing YahvehDocumento1 páginaFearing YahvehJim Roberts Group Official Fan and Glee ClubAún no hay calificaciones

- حقيبة الرسم الفني لتقنية اللحام PDFDocumento63 páginasحقيبة الرسم الفني لتقنية اللحام PDFmahmoud aliAún no hay calificaciones

- Family Engagement Plan PowerpointDocumento9 páginasFamily Engagement Plan Powerpointapi-547884261Aún no hay calificaciones

- LCC EvalDocumento1 páginaLCC EvalAnn CastroAún no hay calificaciones

- Ginza Rabba The Great Treasure The Holy Book of The Mandaeans in English FeaturedDocumento7 páginasGinza Rabba The Great Treasure The Holy Book of The Mandaeans in English FeaturedAnonymous 4gJukS9S0Q100% (1)

- LetrasDocumento37 páginasLetrasOnielvis BritoAún no hay calificaciones

- Interjection: Law Kai Xin Chiew Fung LingDocumento17 páginasInterjection: Law Kai Xin Chiew Fung LingLaw Kai XinAún no hay calificaciones

- Space Programming: Area/Space User'S Area Users No. of UsersDocumento6 páginasSpace Programming: Area/Space User'S Area Users No. of UsersMary Rose CabidesAún no hay calificaciones

- Patents OnlyDocumento19 páginasPatents OnlyJanine SalvioAún no hay calificaciones

- CLAUSES - Kinds, Function, and ExamplesDocumento21 páginasCLAUSES - Kinds, Function, and ExamplesMANGENTE Janna MaeAún no hay calificaciones

- Three Steps of PressingDocumento4 páginasThree Steps of PressingELAD27- GAMINGAún no hay calificaciones

- The Tibu PeopleDocumento21 páginasThe Tibu PeopleAshBarlowAún no hay calificaciones