Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Effectiveness of Formal Observation in Inpatient Psychiatry in Preventing Adverse Outcomes: The State of The Science

Cargado por

lovely99_dyahTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Effectiveness of Formal Observation in Inpatient Psychiatry in Preventing Adverse Outcomes: The State of The Science

Cargado por

lovely99_dyahCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2010, 17, 268273

Effectiveness of formal observation in inpatient psychiatry in preventing adverse outcomes: the state of the science

jpm_1512 268..273

M. MANNA msn rn-bc Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, Inpatient Psychiatry, Baltimore, MD, USA

Keywords: behavioural interventions, mental health, nursing, risk management, self-harm Correspondence: M. Manna Sinai Hospital of Baltimore Inpatient Psychiatry 2401 W. Belvedere Avenue Baltimore MD 21215 USA E-mail: mmanna@lifebridgehealth.org Accepted for publication: 3 August 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01512.x

Accessible summary The term formal observation includes routine or general observation, 30- to 15-min checks, and constant or continuous observation. Although nurses have used formal observation in the psychiatric setting for more than 25 years to monitor patient behaviour, the benets of such approaches are questionable. While formal observation is utilized in a defensive mode to prevent patient harm, the actual efcacy of formal observation is unclear. Additionally, formal observation consumes nursing resources; thus, evidence is necessary to validate and support this intervention. The purpose of this paper is to: determine whether or not research supports the use of formal observation as an effective strategy in preventing potential harm to patients or others; identify any therapeutic benet; identify any gaps in the research. Findings suggest that large gaps continue to exist in the research, but specically: a lack of consensus exists in the literature about formal observation denitions and how it should be carried out regardless of effectiveness; formal observation is rooted in tradition, as little evaluative research exists as to its actual efcacy in reducing harm to patients; historically it is considered negligent to not utilize the practice as a protective measure. Abstract Formal observation in psychiatric settings is a widely accepted intervention employed by psychiatric nurses to reduce the incidence of adverse patient outcomes such as suicides, self-harm, violence and elopements in the psychiatric population. Formal observation includes general or routine observation, observation every 15 or 30 min, continuous or constant observation, and one-to-one observation. While formal observation consumes nursing resources, the efcacy of formal observation in reducing patient risk and providing therapeutic benet remains unclear. To date, no randomized controlled studies exist. The existing qualitative research fails to demonstrate a direct correlation between the act of formal observation and the prevention of adverse patient outcomes. Common in the literature is a debate as to whether formal observation or therapeutic engagement is more benecial. This paper, therefore, identies gaps in the research and synthesizes relevant research regarding the effectiveness of formal observation in preventing adverse outcomes like suicides, self-harm, violence and elopements.

268

2009 Blackwell Publishing

Effectiveness of formal observation

Introduction

Formal observation of patients at risk is an extremely common practice in acute psychiatric facilities (Bowles et al. 2002). The term formal observation includes routine or general observation, 30- to 15-min checks, and constant or continuous observation. General observation means simply that a patient is on a locked unit or 1-h checks. The terms constant observation or continuous observation mean that a patient is within staff vision at all times or within arms length of staff. The practice of observation has long been an integral part of the nurses role in mental health care (BuchananBarker & Barker 2005). Historically, nurses used observation to adhere to the physicians care expectations and ensure patient safety (Cutcliffe & Barker 2002). Although nurses have used observation in the psychiatric setting for more than 25 years, the benets of such approaches are questionable. Observation is demanding and utilizes a large amount of nursing resources. The denition of terms included under the umbrella of formal observation varies from one mental health setting to another on both a national and international level, creating ambiguity and inconsistent application of the intervention. The practice of formal observation also creates a care environment where patients at risk for harm receive a disproportionate amount of nursing services (Bowles et al. 2002). Additionally, the practice of observation may be intrusive and devoid of conversation between the nurse and the patient (Bowles et al. 2002). Despite some of these limitations, observation is the recommended approach for those patients who are deemed to be at risk (Stevenson & Cutcliffe 2006). So how did formal observation become so prominent and permanent? High-prole tragedies have placed mental health practitioners in a defensive mode to stop patient elopements and harm to patients or others. Organizations responded to risk by broadening denitions and formalizing observation policies, mainly to defend themselves against the risk of litigation, which can ensue if risk to the patient is not minimized (Buchanan-Barker & Barker 2005). While formal observation is utilized in a defensive mode to prevent patient harm, the actual efcacy of formal observation to reduce dangerous behaviours such as suicide, self-harm, violence or elopements is unclear. With healthcare costs rising, efcacy of this intervention becomes even more important when comparing cost to benet. Additionally, nurses need to know if and how patients derive therapeutic benet from this intervention and if their time is well spent. With increasing demands placed on nurses and the shortage of nurses in the practice environment, evidence is

2009 Blackwell Publishing

necessary to validate and support the practice of formal observation. The purpose of this paper is to determine whether or not research supports use of formal observation as an effective strategy in preventing potential harm to patients or others and simultaneously identify any therapeutic benet. Additionally, the author will identify any gaps in the research.

Search strategy

Databases were searched for the period of 19962009. The following databases were searched: PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PsycINFO. The American Psychiatric Association and American Psychiatric Nurses Association were searched for information related to history and practice guidelines, position statements, and current research on the subject matter. Keywords included engagement, mental health nursing, observation, risk management, special observation, inpatient mental health, psychiatric nursing and containment. MeSH terms included observation, mental disorders, psychotic disorders, inpatients, risk management and safety management. The search limits included English and publication years from 1996 to 2009. Limits were kept at a minimum to increase the probability of retrieving relevant information.

Selection criteria

Literature was included if it discussed the use of observation in a psychiatric inpatient setting, the indications for its use, impact on suicide, self-harm, violence, and elopements, and its positive and negative therapeutic merits. Nurses perceptions of observations regarding the usefulness of the intervention and impact on the nurse were also incorporated. Because patient perceptions have inuence on the patients behavioural responses, studies discussing patient perceptions regarding the efcacy and benet of formal observation were also included.

Types of evidence found

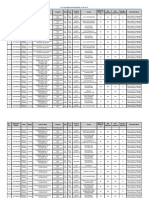

A total of 40 papers were identied of which 10 met the inclusion criteria. The 10 studies included in the literature review were one level II quasi-experimental study; six level III qualitative studies; and two level V studies, one literature review and one expert opinion paper. There was one level IV study, a systematic review, published by the Cochrane Collaboration.

269

M. Manna

Overall summary of evidence

The most widely stated nding was that there was a paucity of research regarding formal observation of psychiatric inpatients. Despite this nding, the available literature dened some issues with conducting research on this topic. The most obvious was the inability to conduct randomized trials because of ethical considerations. Withholding observation could potentially be harmful to patients and staff. Another difculty in conducting research on the topic of formal observation was the wide use of terminology that speaks to the practice of observation. This varied from institution to institution, within countries and even among the very staff engaged in the practice of formal observation. Finally, guidelines for outlining the process of formal observation were inconsistent, as were the interpretations of the activity by the staff. Nurses frequently made unofcial modications to the procedure based on individual judgments, assessments and interpretation of policies (Bowers & Park 2001). The studies acknowledge that the intention of formal observation is safety of patients and staff. However, there is limited information regarding impact on actual safety as opposed to the perception that safety is maintained by both patients and staff. Most of the studies reviewed utilized sample populations from natural settings, such as inpatient psychiatric units. In ve of the qualitative studies, the design methods included surveys, questionnaires or interviews. Theoretical frameworks were embedded in the studies.

mental and control groups were unclear. The comparative time frames during which the groups were studied were not evident. This suggests some inherent difference in the study population and the target population. Additionally, there were other interventions implemented during the time of the programme change like new management, stafng and reduction in size of the unit that potentially inuenced results. With all the changes, it is not possible to say that improved outcomes occurred because of the programme change that included the removal of formal observation. The outcomes reported showed no suicides, a reduction of self-harm by 67%, and a 50% reduction in elopements and a 33% decrease in violent episodes. These data were derived from audits, which are subject to human error, so the accuracy of the data must be considered.

Level III sources of evidence

Qualitative research designs were predominant in the review of literature. Given the outcome of potential death or injury by withholding an observation intervention, it could be considered unethical to conduct higher levels of research that employ such strategies. Four qualitative studies reviewed were descriptive designs (Green & Grindel 1996, Bowers et al. 2000, Gournay & Bowers 2000, Mackay et al. 2005). Three of these studies used various interview techniques such as non-structured interviews. The fourth study conducted retrospective case review. Two additional grounded theory studies were also reviewed. Sample sizes tended to be small, and one study (Green & Grindel 1996) had a random sample. No discussion existed regarding appropriateness of sample size. Theoretical frameworks, embedded in these studies, focused on the construct that formal observation preserves safety. Green & Grindel (1996) attempted to outline the advantages and disadvantages of formal observation. Safety was the most frequently identied advantage of formal observation. The most frequently identied disadvantage was restrictiveness and secondary gains experienced by patients. The study utilized a questionnaire that was pre-tested by three nurses in the same hospital with few revisions. Based on the description of the questionnaire review and the limited piloting of the tool, validity was questionable. The questionnaire was mailed to 312 hospitals from a target population of 1560 selected by a random systematic approach. The response rate was 39.3%. Validity of data is strengthened with the use of questionnaires that were mailed, as respondents are not exposed to the potential bias of an interviewer; however, biases of respondents are unknown to the researcher. The questionnaire utilized in this study contained open-ended questions that

2009 Blackwell Publishing

Level II evidence quasi-experimental

The only level II study was a quasi-experimental pre- and post-case design (Dodds & Bowles 2001). The study was designed to test the belief that formal observation is ineffective, and possibly counter-therapeutic (Dodds & Bowles 2001). The study measured results of patient outcomes in a new care model that excluded formal observation as compared with a traditional care model that included formal observation. Outcome measures included violence, selfharm, suicides and elopements. The setting for the study, a 21-bed inpatient unit, had an average length of stay of 26.8 days. Average length of stay is varied among inpatient settings dependent upon the programme objectives and acuity of patients served, but is generally signicant shorter. The sample was a convenience sample of patients admitted to the inpatient service before and after the intervention. The control group was comprised of mixed-gender general psychiatry patients housed on a 28-bed unit. The experimental group was comprised of all male general psychiatry patients on a 21-bed unit. Sample sizes of experi270

Effectiveness of formal observation

can not only increase the quality and depth of data but also inuence the reliability of what is measured. The nal conclusion was that while inpatient psychiatric units implement observation strategies to ensure safety, it is unclear whether these strategies enhance patient outcomes. However, Green & Grindel (1996) also conversely concluded that the most utilized level of observation, 15-min checks, was likely effective given the low incidence, <5%, of self-injury. The study also suggested further research. However, in general recommendations were inconclusive. Mackay et al. (2005) also conducted a qualitative descriptive study utilizing a purposive sample of 17 nurses on an inpatient psychiatric unit. The purpose was to assess the therapeutic merits of the process of observation based on staff perception. Unstructured qualitative interviews were conducted in person. The results of the interviews identied six areas of therapeutic merit including intervening, maintaining safety of patients and others, de-escalation and management of aggression, ongoing assessment, communication and therapy. Respondents identied that skill level in these areas impacted the success of the practice of formal observation. Analysis was performed by thematic content analysis that is typical when analysing surveys. This technique was used to categorize information. This allows data collection to potentially be replicated and improved the quality of the study. Concerns related to validity inherent in this analytical approach were addressed by comparison and seeking feedback from respondents. The study proposed a balance between observation and engagement and that the least restrictive intervention be utilized to safely manage a patient. While this study discussed how what occurs within the practice of observation could affect patient outcomes, it made no conclusions about the act of observation. There was an assumption that observation was necessary to preserve safety. Gournay & Bowers (2000) conducted another level III qualitative descriptive study. The study retrospectively reviewed 31 cases of suicide and self-harm that occurred during inpatient hospitalizations or shortly thereafter. Of particular interest for this review were the 17 suicide/selfharm incidents occurring while patients were hospitalized and on some level of observation. The sample size was 31 cases selected via a convenience sample because they were litigation cases of patients who attempted or completed suicide. Data collection methods included a review of all available evidence and analysis of the sequence of events by two researchers. The ndings of the study (Gournay & Bowers 2000) implied that other variables like variation in observation implementation could also have inuenced outcomes. This failure in implementation did not necessarily speak to the

2009 Blackwell Publishing

effectiveness of the intervention. In fact, management of patients who pose a risk failed when formal observation was not implemented. Observation protocols were effective in preventing self-harm when staff maintained delity to protocols. Finally, the study recognized the need for staff to keep various unit areas under observation to maintain patient safety and the need for further research. Another qualitative descriptive study conducted by Bowers et al. (2000) looked at observation from the perspective of compliance with existing policies and whether that impacted the safety of the patient. The study ndings stated that extreme variation in terminology and practice likely increased risks to patients. This nding was based on the assumption supported by the literature search that the practice of formal observation affected patient safety. This assumption was reinforced by respondents who agreed that observation was an effective nursing strategy primarily to reduce risk of harm, completed suicide, aggressive behaviour and elopement (Bowers et al. 2000). There were some variable opinions about the efcacy of observation in relation to elderly patients suffering from acute organic mental illness. General observation, a less intense form of formal observation, should be an established part of unit routine and followed rigorously to maintain patient safety. The study recommended evaluative research into the efcacy of continuous observation and standardized guidelines (Bowers et al. 2000). The last two studies in the level III category of evidence are qualitative grounded theory studies that utilize interview methods to gather data (Cardell & Pitula 1999, Cleary et al. 1999) . Cleary et al. (1999) provided insight into the views nurses have towards the practice of observation for suicidal patient in acute inpatient settings. Nurses identied patient safety as a top priority, although observation was stressful because of the safety risk to staff when observing violent patients. Finally, nurses reported that the intrusiveness of observation could actually cause patient aggression. Like other studies (Bowers et al. 2000, Mackay et al. 2005), the assumption is made that formal observation maintained safety, but the study only addressed perceptions and not actual outcomes related to safety like self-harm, violence or elopements. The nal study in the level III category was a qualitative grounded theory study that explored patients experiences to determine whether patients derived any therapeutic benet from formal observation beyond intended protective benets (Cardell & Pitula 1999). The literature review was embedded in the results of the study as in the previous study. However, the review appeared sparse. Participants for the study were selected non-randomly from one state-owned psychiatric facility and two general

271

M. Manna

hospitals with inpatient psychiatric units. Interviews were used for data collection. Each participant had at least two audiotaped interviews to improve data collection and clarify responses. The authors utilized an outside qualitative research expert to validate themes identied by the authors. The authors acknowledged that extraneous factors that inuenced responses such as sleep and medication may have altered participants perceptions (Cardell & Pitula 1999). The most signicant nding was that participants believed the protective aspect of constant observation saved their lives. While some participants reported they looked for ways to harm themselves, the constant vigilant presence of the observers and the limited availability of means demonstrated to participants that these attempts would be futile (Cardell & Pitula 1999). Negative aspects of observation such as a lack of privacy were acknowledged. Also acknowledged was the possibility that the therapeutic benet of observation may be related to observers attitudes and behaviours and not necessarily the observation itself (Cardell & Pitula 1999).

trials that attempt to control confounding variables that might inuence the effectiveness of observation in the psychiatric population.

Level V evidence expert opinion, literature review

Bowers & Park (2001) attempted to address the efcacy of observation and reported that analyses of inpatient suicide showed that six of 57 completed suicides were on special or close observation. Additionally, another survey cited in the review showed that eight out of 20 patients on special observation went on to show self-harming or violent behaviour (Bowers & Park 2001). Bower reported that there was no information that demonstrated that formal observation was an effective strategy to prevent violence. In short, the use of observation was based upon pragmatism, common sense, and tradition (Bowers & Park 2001). While the courts believed that failure to provide observation according to internal guidelines could result in harm, questions regarding efcacy remain. Bowers & Park (2001) further recommended that future research at higher than a qualitative level is dependent upon the development of highly accurate predictive tools. The last source of level V evidence was an expert opinion paper on the research report of the City-128 project (Bowers & Simpson 2007). The opinion paper assessed whether wards that frequently used formal observation had lower rates of self-harm compared with wards where observation was used less. Bowers & Simpson (2007) stated in the paper that one surprising nding was the correlation between intermittent observation and a lower rate of self-harm. They added, however, that because the reduction in self-harm could be the result of something not measured, causality cannot be inferred (Bowers & Simpson 2007).

Level IV evidence systematic review

Level IV evidence generally consists of reviews of pertinent research by known experts or panels of experts in the eld. The systematic review (Muralidharan & Fenton 2006) meets all the criteria for this level of evidence. The review attempted to answer a specic research question: Is there a difference in outcomes when comparing various containment strategies in patients with serious mental disorders who are at risk for harm to self or others? (Muralidharan & Fenton 2006) The literature review was extensive. The search resulted in the review of over 4000 reports. However, only six studies seemed to have potential relevance and upon greater scrutiny could not be included. The six studies focused on pharmacological interventions as opposed to containment strategies like formal observation and thus were excluded. No randomized controlled trials could be identied for inclusion that evaluated the effects of containment strategies. The results of this search validated that the effects of containment strategies like formal observation are based on case studies, descriptive studies, and personal and expert opinion. Implications for practice suggested there was no good-quality evidence to support or refute the use of this strategy (Muralidharan & Fenton 2006). While the use of this strategy may be practical and support safety, it should be used cautiously in the absence of gold standard evidence (Muralidharan & Fenton 2006). The review also recommended that future research include randomized

272

Conclusion

The most prominent nding in all sources of evidence was that while the practice of formal observation is rooted in protection of patient safety; there is little empirical evidence to support it (Bowers et al. 2000). In fact, this gap in the research was identied in all the sources of evidence reviewed. There was also agreement in the evidence about issues surrounding observation that must be dealt with: variations among denitions of levels of observations, adherence to the level of observation interventions, skill and licensure levels of staff carrying out the intervention, lack of consistent policy and clinical guidelines to direct the practice, and extraneous variables like observer attitude and behaviour during the observations of patients. The biggest deterrent to conducting higher levels of research is the ethical dilemma of withholding potentially life 2009 Blackwell Publishing

Effectiveness of formal observation

protecting intervention to ascertain the effectiveness of the intervention. The legal opinions stated in the sources were in agreement that withholding this intervention or failure to perform it accurately is considered negligence (Bowers & Park 2001). Large gaps continue to exist in the research. It is universally acknowledged that observation is essential to maintain the safety of a vulnerable population; yet, there is lack of consensus in the literature about what it is and how it should be carried out regardless of effectiveness. This important action is based in tradition and practicality, not research (Bowers et al. 2000). The practice is a costly intervention and can account for up to 20% of nursing budgets (Bowers & Park 2001). It is staff intensive and in some instances decreases staff satisfaction. Patients can perceive it as intrusive and have, in some instances, minimized impulses to escape the observation process. Yet, legally it is considered negligent to not utilize the practice as a protective measure. Despite all of these concerns, there is little evaluative research into its actual efcacy (Bowers et al. 2000) in a quantitative way as measured by reduction in self-harm incidents, violence towards others or elopements.

References

Bowers L. & Park A. (2001) Special observation in the care of psychiatric inpatients: a literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 22, 769786. Bowers L. & Simpson A. (2007) Observing and engaging. Mental Health Practice 10, 1214. Bowers L., Gournay K. & Duffy D. (2000) Suicide and self-harm in inpatient psychiatric units: a national survey of observation policies. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32, 437444.

Bowles N., Dodds P., Hackney D., et al. (2002) Formal observations and engagement: a discussion paper. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 9, 255260. Buchanan-Barker P. & Barker P. (2005) Observation: the original sin of mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 12, 541549. Cardell R. & Pitula C. (1999) Suicidal inpatients perceptions of therapeutic and non therapeutic aspects of constant observation. Psychiatric Services 50, 10661070. Cleary M., Jordan R., Horsfall J., et al. (1999) Suicidal patients and special observation. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 6, 461467. Cutcliffe J. & Barker P. (2002) Considering the care of the suicidal client and the case for engagement and inspiring hope or observations. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 9, 611621. Dodds P. & Bowles P. (2001) Dismantling formal observation and refocusing nursing activity in acute inpatient psychiatry: a case study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 8, 183188. Gournay K. & Bowers L. (2000) Suicide and self-harm in inpatient psychiatric units: a study of nursing issues in 31 cases. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32, 124131. Green J. & Grindel C. (1996) Supervision of suicidal patients in adult inpatient psychiatric units in general hospitals. Psychiatric Services 47, 859863. Mackay I., Paterson B. & Cassells C. (2005) Constant or special observations of inpatients presenting a risk of aggression or violence: nurses perceptions of the rules of engagement. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 12, 464 471. Muralidharan S. & Fenton M. (2006) Containment strategies for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3, 110. Stevenson C. & Cutcliffe J. (2006) Problematizing special observation in psychiatry: foucault, archaeology, genealogy, discourse and power/knowledge. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13, 713721.

2009 Blackwell Publishing

273

Copyright of Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing is the property of Blackwell Publishing Limited and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

También podría gustarte

- Correctional Health Care Patient Safety Handbook: Reduce Clinical Error, Manage Risk, and Improve QualityDe EverandCorrectional Health Care Patient Safety Handbook: Reduce Clinical Error, Manage Risk, and Improve QualityCalificación: 2 de 5 estrellas2/5 (1)

- Patient Safety in Psychiatric Inpatient Care A Literature ReviewDocumento12 páginasPatient Safety in Psychiatric Inpatient Care A Literature ReviewcigyofxgfAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Nurse FinDocumento5 páginasResearch Nurse FinFredrickAún no hay calificaciones

- Using Client Outcome Monitoring As A Tool For SupervisionDocumento5 páginasUsing Client Outcome Monitoring As A Tool For SupervisionDianaSantiago100% (1)

- Quantitative Article Critique and SummaryDocumento8 páginasQuantitative Article Critique and SummaryEmmanuelAún no hay calificaciones

- Integrative Literature CompletedDocumento20 páginasIntegrative Literature Completedapi-431939757Aún no hay calificaciones

- Summary ResearchDocumento6 páginasSummary ResearchLance SilvaAún no hay calificaciones

- NURS 682 Care Coordination and Role of The Advanced Practice NurseDocumento3 páginasNURS 682 Care Coordination and Role of The Advanced Practice NurseParya VAún no hay calificaciones

- Shinelle Research Article UpdatedDocumento7 páginasShinelle Research Article UpdatedZeeshan HaiderAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethical Issues in Healthcare ManagementDocumento44 páginasEthical Issues in Healthcare ManagementTravel with NiroAún no hay calificaciones

- Psychology and Health Notes - CIE Psychology A-LevelDocumento18 páginasPsychology and Health Notes - CIE Psychology A-LevelRajasekar KrishnasamyAún no hay calificaciones

- CF Rca TemplateDocumento8 páginasCF Rca TemplateEsteban García EcheverryAún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative Article CritiqueDocumento9 páginasQualitative Article CritiqueJohn Smith100% (2)

- Evidence Based Practice in NursingDocumento86 páginasEvidence Based Practice in NursingKrea kristalleteAún no hay calificaciones

- Evidence Based Practice in NursingDocumento86 páginasEvidence Based Practice in NursingKrea kristalleteAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Handover and Patient Safety Literature Review Report 2005Documento5 páginasClinical Handover and Patient Safety Literature Review Report 2005gw163ckjAún no hay calificaciones

- EBP Deliverable Module 2Documento6 páginasEBP Deliverable Module 2Marian SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- 0rder 343 NRS-493-ASSIGNMENT 3 Literature ReviewDocumento6 páginas0rder 343 NRS-493-ASSIGNMENT 3 Literature Reviewjoshua chegeAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: Research Designs 1Documento7 páginasRunning Head: Research Designs 1Zeeshan HaiderAún no hay calificaciones

- Sample - Critical Review of ArticleDocumento11 páginasSample - Critical Review of Articleacademicproffwritter100% (1)

- Bmjopen 2014 006578Documento18 páginasBmjopen 2014 006578Ortopedia HGMAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Physicians and Nurses Ask (Or Don 'T) About Partner Violence: A Qualitative AnalysisDocumento12 páginasWhy Physicians and Nurses Ask (Or Don 'T) About Partner Violence: A Qualitative Analysisionut pandelescuAún no hay calificaciones

- Detailed NotesDocumento18 páginasDetailed NotesAleeza MalikAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review of Palliative CareDocumento8 páginasLiterature Review of Palliative CareHendy LesmanaAún no hay calificaciones

- ResearchDocumento22 páginasResearchsheebaAún no hay calificaciones

- Diabetes Mellitus Autoimmune Insulin Beta Cells Pancreas Polyuria Polydipsia PolyphagiaDocumento37 páginasDiabetes Mellitus Autoimmune Insulin Beta Cells Pancreas Polyuria Polydipsia PolyphagiaVishuAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: Nursing Practise Case Studies 1Documento7 páginasRunning Head: Nursing Practise Case Studies 1johnmccauleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento8 páginasAnnotated BibliographyEunice AppiahAún no hay calificaciones

- Open VsDocumento16 páginasOpen Vsapi-482726932Aún no hay calificaciones

- Yuan Aj MQ Patient Safety Medical HomeDocumento28 páginasYuan Aj MQ Patient Safety Medical HomeAdebisiAún no hay calificaciones

- Quality and Safety Synthesis PaperDocumento6 páginasQuality and Safety Synthesis Paperapi-252807964Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research Final DefenseDocumento67 páginasResearch Final DefenseNellyWataAún no hay calificaciones

- Study On Infection ControlDocumento8 páginasStudy On Infection ControllulukzAún no hay calificaciones

- Tni CoverpageDocumento3 páginasTni Coverpageapi-291660325Aún no hay calificaciones

- Comprehensive Patient Assessment in MedicalDocumento5 páginasComprehensive Patient Assessment in MedicalMark Russel Sean LealAún no hay calificaciones

- Evidence-Based Nursing: The 5 Steps of EBNDocumento13 páginasEvidence-Based Nursing: The 5 Steps of EBNRanjith RgtAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: Pediatrics Project 1Documento9 páginasRunning Head: Pediatrics Project 1Best EssaysAún no hay calificaciones

- Nursing Evidence Based Practice Research Paper TopicsDocumento8 páginasNursing Evidence Based Practice Research Paper TopicssacjvhbkfAún no hay calificaciones

- Reaction ResearchDocumento5 páginasReaction Researchapi-282416142Aún no hay calificaciones

- Capstone PaperDocumento6 páginasCapstone Paperapi-353940265Aún no hay calificaciones

- Activity 1 and 2Documento5 páginasActivity 1 and 2Dustin AgsaludAún no hay calificaciones

- The Importance of Evidence-Based Practice in NursingDocumento9 páginasThe Importance of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursingapi-740215605Aún no hay calificaciones

- Devalk Quality Improvement Project PaperDocumento6 páginasDevalk Quality Improvement Project Paperapi-272959759Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research Proposal 1.1 Background of The StudyDocumento9 páginasResearch Proposal 1.1 Background of The StudyFranklin GodshandAún no hay calificaciones

- Studyoninfectioncontrol CHENNAIDocumento8 páginasStudyoninfectioncontrol CHENNAIDickson DanielrajAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review EbpDocumento6 páginasLiterature Review Ebpfvffv0x7100% (1)

- He U.S. Hospital System Suffers From ShortfallsDocumento8 páginasHe U.S. Hospital System Suffers From Shortfallsjoy gorreAún no hay calificaciones

- FPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1Documento17 páginasFPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1FrancisAún no hay calificaciones

- Factors Influencing NursesDocumento6 páginasFactors Influencing Nursesangel_reign04Aún no hay calificaciones

- Management Vol1 Issue2 Article 8Documento45 páginasManagement Vol1 Issue2 Article 8martin ariawanAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Survive The Medical Misinformation MessDocumento8 páginasHow To Survive The Medical Misinformation MessTameemAún no hay calificaciones

- 1.pdf JsessionidDocumento39 páginas1.pdf JsessionidAlvin Josh CalingayanAún no hay calificaciones

- Lorne Basskin - Practical PE ArticleDocumento5 páginasLorne Basskin - Practical PE ArticleCatalina Dumitru0% (1)

- Introduction To Nursing Research Part 1Documento22 páginasIntroduction To Nursing Research Part 1Ciedelle Honey Lou DimaligAún no hay calificaciones

- Nur Final PaperDocumento9 páginasNur Final Paperapi-404050277Aún no hay calificaciones

- Infeksi Nifas PublisherDocumento4 páginasInfeksi Nifas PublisherYayha AgathaaAún no hay calificaciones

- Health Education: Evidenced Based PracticesDocumento58 páginasHealth Education: Evidenced Based PracticesChantal Raymonds90% (41)

- Clinical Nursing JudgementDocumento5 páginasClinical Nursing Judgementapi-400333454Aún no hay calificaciones

- How To Change Nurses' Behavior Leading To Medication Administration Errors Using A Survey Approach in United Christian HospitalDocumento10 páginasHow To Change Nurses' Behavior Leading To Medication Administration Errors Using A Survey Approach in United Christian HospitalyyAún no hay calificaciones

- 420 Research PaperDocumento12 páginas420 Research Paperapi-372913673Aún no hay calificaciones

- Non-Contact Forehead Infrared Thermometer User Manual: M. Feingersh & Co - LTDDocumento16 páginasNon-Contact Forehead Infrared Thermometer User Manual: M. Feingersh & Co - LTDKamal SemboyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Mechanics of Crushing Sugar Cane - Murry and HoltDocumento77 páginasThe Mechanics of Crushing Sugar Cane - Murry and HoltRomina SalazarAún no hay calificaciones

- Francis Bacon: Life, Legacy & WorkDocumento29 páginasFrancis Bacon: Life, Legacy & WorkCARL JUN DELA CRUZAún no hay calificaciones

- Topic 11-SD Edit-Qualitative Data AnalysisDocumento14 páginasTopic 11-SD Edit-Qualitative Data AnalysisLieya Nur Irdina RuzaimanAún no hay calificaciones

- ThesisDocumento33 páginasThesisSajalShakya50% (2)

- Safety-II Na American AirlinesDocumento44 páginasSafety-II Na American AirlinesFrancisco Silva100% (1)

- FrontiersDocumento10 páginasFrontiersghanimAún no hay calificaciones

- Learning Styles Kolb QuestionnaireDocumento6 páginasLearning Styles Kolb QuestionnaireAkshay BellubbiAún no hay calificaciones

- Physics NewtonDocumento7 páginasPhysics NewtonAhillan MAún no hay calificaciones

- Research DesignDocumento16 páginasResearch DesignRajaAún no hay calificaciones

- Presentation of The Paper "The Systematic Review of Literature in LIS: An Approach"Documento4 páginasPresentation of The Paper "The Systematic Review of Literature in LIS: An Approach"Bright WayAún no hay calificaciones

- Inter SubjectivityDocumento3 páginasInter SubjectivityDebby FabianaAún no hay calificaciones

- Observing: Kpli Science Minor Lesson Notes BY Sylvester Saimon Simin SMD, KTTCDocumento9 páginasObserving: Kpli Science Minor Lesson Notes BY Sylvester Saimon Simin SMD, KTTCssskguAún no hay calificaciones

- Consumer Behavior - Test Bank SchiffmanDocumento33 páginasConsumer Behavior - Test Bank SchiffmanEnsoyAún no hay calificaciones

- Star Trek Adventures - Sciences Division Supplement PDFDocumento140 páginasStar Trek Adventures - Sciences Division Supplement PDFGorka Diaz100% (6)

- Slime Journal For StudentsDocumento22 páginasSlime Journal For StudentsKitsuikoAún no hay calificaciones

- Illusory Correlations in Graphological Inference - King & KoehlerDocumento13 páginasIllusory Correlations in Graphological Inference - King & KoehlerCarlos AguilarAún no hay calificaciones

- List of AICTE Approved Colleges in Madhya PradeshDocumento125 páginasList of AICTE Approved Colleges in Madhya Pradeshakjfjlwf wejenweAún no hay calificaciones

- Jbi Critical Appraisal Checklist For Randomized Controlled TrialsDocumento4 páginasJbi Critical Appraisal Checklist For Randomized Controlled TrialsNatasya Cindy SaraswatiAún no hay calificaciones

- RM McqsDocumento27 páginasRM McqssonuAún no hay calificaciones

- Practical Research1 - Q1 - M4-Differentiating Quantitative From Qualitative ResearchDocumento13 páginasPractical Research1 - Q1 - M4-Differentiating Quantitative From Qualitative ResearchKaye ToledanaAún no hay calificaciones

- Galileo ReadingDocumento9 páginasGalileo ReadingIrina BodeAún no hay calificaciones

- Science & TechnologyDocumento397 páginasScience & TechnologyHarman VishnoiAún no hay calificaciones

- Practical Research 2: (With Learning Activity Sheets) Quantitative Research For Senior High SchoolDocumento54 páginasPractical Research 2: (With Learning Activity Sheets) Quantitative Research For Senior High SchoolRodelyn Ramos GonzalesAún no hay calificaciones

- Collecting Primary DataDocumento3 páginasCollecting Primary DataHicham ChibatAún no hay calificaciones

- STS 1Documento7 páginasSTS 1Jolie Mar ManceraAún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative ResearchDocumento3 páginasQualitative ResearchLeady Darin DutulloAún no hay calificaciones

- GROUP 4 Conceptual Framework Research DesignDocumento19 páginasGROUP 4 Conceptual Framework Research DesignMark Billy RigunayAún no hay calificaciones

- Approaches To ResearchDocumento18 páginasApproaches To ResearchDanushri BalamuruganAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Do A Coaching Cycle With The Five QuestionsDocumento46 páginasHow To Do A Coaching Cycle With The Five Questionscansu sezerAún no hay calificaciones

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (32)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDe EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsAún no hay calificaciones

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)De EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Calificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (404)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDDe EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeCalificación: 2 de 5 estrellas2/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDe EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (170)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesDe EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (1412)

- Empath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainDe EverandEmpath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (95)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (82)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDe EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDe EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDe EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsAún no hay calificaciones

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDe EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (46)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (110)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (6)

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeDe EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2)

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingDe EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingCalificación: 1 de 5 estrellas1/5 (2)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsDe EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (39)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDe EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (254)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlDe EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (60)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassDe EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (27)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDe EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (8)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDe EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (328)

- Summary: $100M Offers: How to Make Offers So Good People Feel Stupid Saying No: by Alex Hormozi: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe EverandSummary: $100M Offers: How to Make Offers So Good People Feel Stupid Saying No: by Alex Hormozi: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (17)