Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

20163874

Cargado por

dovescryDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

20163874

Cargado por

dovescryCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Trustees of Boston University

Heidegger's Greeks Author(s): Glenn W. Most Reviewed work(s): Source: Arion, Third Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 2002), pp. 83-98 Published by: Trustees of Boston University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20163874 . Accessed: 11/09/2012 06:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Trustees of Boston University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Arion.

http://www.jstor.org

Heidegger's Greeks

GLENN W. MOST

his writings

major one or the other of two forms. On often names formed specific ancient Greek reader can identify without attested

1.VJL ARTIN HEIDEGGER FREQUENTLY refers in to the Greeks, more so perhaps than any other since Nietzsche. These references take philosopher the one hand, Heidegger individuals whom the in difficulty authors, as more to whose or less trans

well-known, mitted works, This

ancient Greek

or at least certain parts thereof, he is alluding. fact raises a first set of questions: which Greeks does name by preference, and why these ones, and why Heidegger not others? On the other hand, he also tends to refer to a group calls, cially of nameless simply, in certain and non-individualized "the Greeks." people whom he In some of his texts, and espe of these, such references cease to be

parts scattered and punctual, and assume instead a pecu merely liar density and consistency. For example, within a few pages to Metaphysics, in his Introduction "Im writes, Heidegger Zeitalter der ma?gebenden Entfaltung bei den Griechen, durch die Philosophie im Ganzen das Fragen nach dem Seienden als solchem seinen wahrhaften nahm, nannte man das Seiende Anfang tyv?iq" ("In the age of the first and authoritative develop abendl?ndischen of. Western der ersten und

ment

the Greeks, among philosophy through as such as a whole had its true which the question of what is GA 40.15),x or again, beginning, what is was named <|ruoT?," "Die Griechen haben nicht erst an den Naturv or gangen er . ." ("It was not first of all on the ba fahren, was fyvaiq ist. sis of natural processes that the Greeks experienced what

84 heidegger's

greeks

" . . . , 17), or again, "Das Seiende als solches im (Jr?cic is nennen die Griechen Ganzen tyvoxc," ("The Greeks name what is as such as a whole tyvGiq," 18), or finally, "Wir set das Seelische, Be ?Psychische?, seelte, Lebendige entgegen. All dieses aber geh?rt f?r die Als Gegenerscheinung Griechen auch sp?ter noch zur <|>?Gtc. Physischen das tritt heraus, was die Griechen O?ai?, Setzung, Satzung nen nen oder vofAO?,Gesetz, Regel im Sinne des Sittlichen" ("We to the physical the 'psychical,' the spiritual, set in Opposition animate, living. But all of this belongs for the Greeks even later to (|ruai?. As the opposite appears what phenomenon call G?ai?, positioning, the Greeks statute, or vouo?, law, is 18). Another rule, in the sense of the ethical," example supplied by a few pages of his essay "Vom Wesen und Be Physik B, 1": "F?r die Griechen griff der tyvoi? Aristoteles, in das Unverbor ?das Sein? die Anwesung aber bedeutet " ("But for the Greeks gene 'Being' means presentification

into the unconcealed," GA 9.270), or "Aristoteles . . . be

zen dem

wahrt

von jeher als das Wesen des nur das, was die Griechen . . . preserves the erkannten" ("Aristotle ??yeiv only what as the essence of ??yeiv," 279), Greeks had long recognized or again, "An sich hat X?yeiv mit Sagen und Sprache nichts zu tun; wenn greifen, dann das Sagen als ??yeiv be jedoch die Griechen des We liegt darin eine einzigartige Auslegung sens von Wort und Sage, deren noch unbetretene Abgr?nde keine sp?tere ?Sprachphilosophie? je wieder ahnen konnte" to do with conceive speaking and lan speaking as Xeyeiv, of the essence interpretation no abysses, still untrodden,

("In itself X?yeiv has nothing if the Greeks guage; however, then there lies therein

a unique of word and language, of whose of language' was later 'philosophy even

ever capable of having . . . an inkling," 280), or finally, "das Entscheidende aus der Ruhe besteht darin, da? die Griechen die Bewegtheit . . . consists in the fact that the ("What is decisive begreifen" conceive motion striking and raises a second characteristic question: on the basis of rest," 283-84). This of Heidegger's linguistic usage just who are these anonymous

Greeks

Glenn W. Most

85

Greeks

can he is referring? Both sets of questions in a single one: who are Heidegger's Greeks? I shall try to approach an answer to this question by pro in advance for their in posing six theses, and I apologize to whom be summarized evitable to Heidegger, to the Greeks, crudeness and to my readers. They are intended to elicit discussion rather than to terminate discussion, if possible to a some and to contribute clearer understanding both of what Heidegger was ac and of one role at least that ancient Greek tually doing thought was able to play inmodern German thought. Iwrite classicist not only and student of the classical for professional philosophers readers more widely interested literature, and cul philosophy,

what

here as a professional tradition, and Iwrite

but also for non-professional in the interrelations between

ture. Heidegger himself sometimes took care to distinguish his own philosophical reconstruc project from a historical tion of the realities of ancient Greece that would satisfy the H 309-10); criteria of professional classical scholarship (e.g., this fact, so far from rendering superfluous the question of who Heidegger's Greeks were, makes it all the more in just not only No doubt Heidegger's adherents?and teresting. they?will Wissenschaft find inmy (science, remarks further proof for his thesis that scholarship) and (Heidegger's) Denken

one another. "In (thought) are incapable of understanding an ihnen vorbeige mitten der Wissenschaften denken, hei?t: hen, ohne sie zu verachten" ("To think amidst the sciences means: to go past them without them," H 195): despising but the task of scholarship must remain that of so, maybe questioning thought, respectfully, as it goes by. are a pagan Gospel. Whatever there might be concerning the iden uncertainty of the persons whom Heidegger's references to the Greeks tity denote, there can be little doubt about the function these ref erences play within the rhetorical strategy of his texts. Greeks To understand morning this function, imagine that it is Sunday in a small town in southwestern Germany. We find 1. Heidegger's

86 HEIDEGGER'S

GREEKS

does not matter ourselves, of course, in a church?it ent purposes whether it is a Catholic or a Lutheran

for pres one. Be

a priest or a minister is standing. fore the seated congregation, He accuses He addresses them in tones the worshippers. which are partly peremptory, partly compassionate, of having fallen away from their highest capabilities and of having for gotten the supreme Being; they have been living thoughtlessly

themselves and carelessly, he says, and have been dedicating to the merely transient pleasures of today's world. Not only does he argue and accuse: he supports his claims by reference to prove his point by text. He undertakes a short passage from the Bible, preferably from the New citing and by interpreting it in as much detail as his in Testament, ventiveness patience will permit. The wor silence. When he has finished, they shippers all say, "Amen," go home, and have a big lunch. My first thesis is that Heidegger's writings tend very often to ser adopt the tone and rhetorical strategies of the Christian and his audience's listen in abashed I have invited you just now to imagine, but that when let alone the Sep do it is never the Greek New Testament, they a German translation of either), to which he de tuagint (or to an authoritative

mons

votes his spiritual exegesis, but other Greek texts, prose and poetry, which provide him with what can most precisely be de scribed as a pagan Gospel. They give him a lever with which he can try to dislodge modernity by reminding us of what we may be made to believe that we knew once but have since for gotten. He seems to believe that, by exploiting what can be taken to be their originality and priority, their unquestionable authenticity, he can convince us to share his view of everything that is wrong with technological world. and Moscow?but by Athens, not by Jerusalem or Rome. Some version of this idea has been a commonplace every European phistic of Roman Italian Renaissance mantic Humanism Renaissance at least since the facticity of our lives in this modern, Freiburg must be saved from New York of So

the Second

the Imperial times, including especially of the fifteenth century, the German Ro of the 1790s, and finally the Third Hu

Glenn W. Most

87

manism Christian

that Werner have

Renaissances

in the 1930s. Such Jaeger propagated or anti been typically non-Christian in their fundamental orientation (which is not to

say that there were not some individuals of profound Chris tian faith among their proponents), yet they have tried to some of the very same ends that Christianity achieve has of ten sought?the moral of the individual, the improvement of a spiritual community, foundation the rejection of the blandishments of the material world surrounding us in favor of spiritual values manifested in great works of the past? and they have used some of the very same techniques. This is one reason, and perhaps the most basic one, for some of of Heidegger's for 1947 "Letter on Humanism": there can be no doubt that Heidegger?who in that essay ex of European Humanism plicitly rejects the traditions (GA to what and opposes his own philosophy is usually 9.320) the oddities (330, 334) to oppose "das Inhumane" 345-46, 348) and takes considerable philosophical project as a new and one that truly reflects the dignity only firmly understood as Humanism but nonetheless ("the claims 340, inhumane," to define his own pains the higher Humanism, of man (342, 352)?is

in fact malgr? lui a Humanist himself. The relation between Heidegger is of and Christianity course a highly complex one (see e.g., H and problematic 202-3). But what is certain is that the stark contrast between and religious belief with which such texts as his philosophy Introduction language and of Roman for being not only a Roman me diation but also a (and hence betrayal) of Greek philosophy, Christian and medieval Scholastic mediation of Greek pagan frequent culture?which he contests ism?programmatically discourse philosophical Christian which exclude which the Christian Gospels from a has evidently been shaped by is opened up a textual space, toMetaphysics opens of the Latin denigration (GA40.8-9), as well as his

traditions. Thereby the pagan Greeks can come to fill. So too, Heidegger's method of presentation of Greek texts is reminiscent of the use of the Gospels in Christian sermons:

88 heidegger's

greeks

trans quotation of short passages in translation; explanatory or more precisely paraphrase, which works out the lation, seen in the text by packing them tendentiously implications itself; and a lengthy exegesis which aims out everything the text. implied or concealed within And yet, viewed within this light, Heidegger's mode of exege sis is very odd: for he is almost always at considerable pains into the translation to work its apparent against the text, to struggle against in support of some other level of signification which meaning own variety of is far from obvious. Thus even ifHeidegger's to work pneumatic is ultimately derived from a theological exegesis in him it takes on an extreme and problematic tradition, form. To understand this, let us turn to the second thesis. Greeks terms. are the speakers of a lexicon of primal

2. Heidegger's

philosophical It is a striking fact about Heidegger's that he never interprets at length a whole

use of the Greeks

text of Greek po or philosophy to end, but instead fo from beginning etry cuses restrictively upon short sections, chapters, indeed often In dealing with longer texts that have been only sentences. transmitted them

to fragment in extenso, he evidently prefers into smaller ones. What is more, he seems strongly to in a fragmen prefer to deal with texts that are transmitted tary form rather than with ones still extant in their entirety, and in interpreting the surviving testimony of ancient Greek to especially he devotes most of his attention philosophy ex brief fragments. One extreme, but not uncharacteristic, is provided by What Does Thinking Mean?: here he one quarter of the whole book upon a single expends about But what he apparently line of Parmenides (WhD 105-49). most prefers to interpret is not even Greek texts, not even ample of the fragmentary Greek ones, but above all single words of single Greek Greek interpretation language. Heidegger's words tends to take one or the other of two forms: either he text, which interprets a transmitted more syntactical units, by explaining is composed of one or one by one all or most

Glenn W. Most

89

or at least some of the individual words he simply words?for discusses a

example, text containing tion from any particular them. as an interpreter of Greek thought, consis So Heidegger, fragments to parts, sentences tently prefers parts to wholes,

it contains; or else of individual small number key isola ?krfieia, Xoyo?, voe?v?in tyvaiq,

to fragments, and single words to sentences. In fact, he often the purported goes even further, preferring etymological to the attested meanings roots of words of the words them be said to lexicalize Greek selves. Thus Heidegger may thought. He of individual almost infinitives mits Greek language as a collection case and ignores in the nominative substantives other parts of speech than nouns or any completely seems to see the Greek as well as the whole sentences structure of syntax which per to yield a meaning. do not actually write, and if they do

Greeks Heidegger's write, the less they write the better. The best Greeks, for Hei speak, and who speak degger, seem to be ones who merely substantives with which single, heavily charged they tacitly connect unspoken compose enounce They

and profoundly meditated but highly sophisticated associations. Greeks do not so much Heidegger's texts as rather literary or philosophical to one another these primal philosophical simply terms.

look at one another, say (Jruaic, and nod slowly. That is must why Heidegger interpret the surviving Greek texts so for he is trying to re often against their apparent meaning, store them from the condition of factitious actual utterances, to which thentic they have fallen, back to their originary, status as a primal archive of philosophy. Greeks are only some Greeks. about "the Greeks." fully au

3. Heidegger's

Heidegger speaks the real Greeks of the ancient world

often

But most

of of

seem to be a matter

indifference, or even ignorance, to him. complete First of all, he turns the Greeks into the Greek language: it is only insofar as the Greeks are producers of written texts or speakers of the Greek language that they interest him. Hei

9o

heidegger's

greeks

of, Greek displays no interest in, or even awareness Greek warfare, Greek Greek politics, economics, history, Greek cuisine, Greek sports, Greek slavery, Greek families, or Greek children. He hardly mentions Greek Greek women, degger religion, and?with apparently only one exception?does so as to explain certain aspects of Greek philosophy, only example referring to Artemis as a context for Heraclitus so for (GA tem

is his discussion of the Greek that exception 55.14-19); ple in his essay "The Origin of theWork of Art," where how ever it is difficult to imagine what if anything the reflections

associates with that building have to do with Heidegger or modern as understood Greek religion scholar by ancient So the Greeks, whom Heidegger celebrates as ship (h 30-44). of a nature still untainted by the de the last representatives in fact seem to interest him only fects of Western civilization, as the producers of the traditional monuments of high cul ture. But even here, Heidegger such other forms of ignores Greek high culture as art and sculpture and focuses exclu he tends to neg sively upon Greek words. Characteristically, of ancient thinkers, except in his lecture lect the biographies on Heraclitus, where however he radically reinterprets a few in order to provide them anecdotes of doubtful authenticity with a deep philosophical (GA 55.5-13). meaning But second, within this technique of turning the Greeks into Greek, Heidegger performs a severe generic and histor ical restriction of the field of relevant evidence. Generically, and the loftiest forms of poetry, Homer's only philosophy tragedies, enter his epics and Pindar's odes and Sophocles' Greeks do not write comedies, field of vision. Heidegger's love po romances, invectives, oratory, histories, epigrams, texts; in fact, even etry, letters, laws, scientific or medical within lyric poetry and tragedy they do not write Sapphic is odes or Euripidean tragedies. And historically, Heidegger in the very earliest period of Greek philoso interested only apparently phy and poetry. Among Greek poets, Heidegger Hellenistic cites none later than Sophocles. and Imperial litera Greek poetry and prose?to say nothing of Byzantine

Glenn W. Most

91

ture?seem Greek very

to be entirely absent for Heidegger philosophy, Plato der Griechen.

from his it seems

reading. As for to die out at the ist es mit der

latest with

and Aristotle?"So

Philosophie Ende" ("So it is with

Sie ging mit Aristoteles gro? zu It came of the Greeks. the philosophy

GA 40.18). The great to an end grandly with Aristotle," and Imperial Greek philosophy?the schools of Hellenistic Academy cureanism most and and Cynicism, the Lyceum, Epi Scepticism left al and Neoplatonism?have and Stoicism When he mentions Simplicius, transmits?and Only them, distorts?frag earn the Presocratics only Anaximander,

no trace in his writings. it is only because Simplicius of Presocratic full admiration?and

ments his

philosophy. among

and Parmenides. Heraclitus, Thus Heidegger's Greeks, not just speakers of Greek),

insofar as they are authors (and are the authors of a very small selection of celebrated texts, from Homer through Aristotle, on the fifth century Par with the emphasis (Heraclitus, rather than on earlier or later periods. menides, Sophocles) This to a selection from the canon of school list corresponds since the authors taught in German humanistic Gymnasien a portentous here freighted with nineteenth century?but weight. Greeks are Nietzsche's narrow Greeks.

metaphysical 4. Heidegger's

among the extant restrictively Heidegger's texts of Greek literature and philosophy is strikingly reminis cent of the canonizations by Friedrich Nietzsche performed selection within In all areas of Greek culture, Niet the same domains. zsche's general preference for the archaic in all its manifesta earlier over later periods, the tions led him to privilege over the Hellenistic and Imperial, the Preclassical Classical To be sure, within the field of Greek poetry, one hand, Nietzsche on the much preferred tragedy to all other earlier and later Greek poetic genres, and within tragedy to Aeschylus and Euripides. Of he much preferred Sophocles course, in these choices Nietzsche was merely following, or, over the Classical.

92

heidegger's

greeks

a new rationale for, preferences which can to antiquity itself but which became newly current in the nineteenth in the wake of century, especially August Wilhelm Schlegel's highly influential lectures on dra matic poetry. But in his marked preference within Greek phi better, providing be traced back over Plato and all later Greek on the other hand, Nietzsche was innovative and philosophy, It was influential. above all Nietzsche who be directly losophy for the Presocratics to contemporary and subsequent German queathed thought the view of the earliest Greek thinkers as an ideal community of isolated, heroic, polemical and misunderstood individuals whose more fragmentary philosophical than the optimistic, profound that followed the caesura marked insights were nobler and banal, systematic by Socrates or Plato. In even speak of Nietzsche's philosophy. as Nietzsche did, a crucial negative schools

deed, to a certain extent, one may "invention" of the concept of Presocratic

the same Greeks Heidegger emphasizes with the exception of Socrates, who plays role who in Nietzsche's is apparently

ings?presumably rate from Plato, Heidegger. fer above Nietzsche had

of Greek philosophy but understanding absent from Heidegger's writ entirely or too hard to sepa he is too dialogical, for the monological and anti-Platonic seems to pre linked with

the Presocratics, Heidegger Among all Heraclitus, who was closely

in the eyes of many Germans. Nietzsche himself a particular to Heraclitus and assigned prominence pathos among those he called "the tyrants of the spirit" as the most

and philosophically tragically philosophical tragic in the tragic age," and even of "philosophy representative Nietzsche's in the preface to his opponent Hermann Diels, critical edition of the fragments of Heraclitus, had pointed between the ancient Greek philosopher and the contemporary German one. Did they not both compose in the form of striking, memorable, and highly philosophy did they not both assume a violently metaphoric aphorisms, stance with regard to the dominant polemical ideologies of their time, did they not both address a spiritual elite, were out the affinities

Glenn W. Most

93

they not both notoriously melancholy? differences Of course there are unmistakable degger's interpretation clitus, and Nietzsche's. these differences, emphasize of the Presocratics, himself Heidegger not

between Hei least of Hera

at pains to an impres and thereby creates on his part from Nietzsche's sion of greater independence view of Greek philosophy than is really the case. In fact, as a tactical de seems to make use of Nietzsche Heidegger vice to help him position himself over and against other con is often temporary ways of reading Greek philosophy. In particular, Heidegger had to negotiate between two very to this subject matter which were dom different approaches in contemporary German intellectual culture. On the one hand, the classical philologists claimed Greek philosophy as their own because it was Greek philosophy. Scholars like inant Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff Sein Leben and positivistic (Aristoteles 1893; Platon: und seine Werke, und Athen, 1918) devoted a

to these interpretation resolutely historicizing the biographical, and political texts, emphasizing historical, contexts of their situation of origination and explicitly deny philosophical validity. On the ing to them any permanent other hand, contemporary German above all philosophers, as the Marburg claimed Greek philosophy Neokantians, their own because Hermann Cohen like philosophy. Philosophers and Paul Natorp Ideenlehre, (Piatons 1878) in den Idealismus, (Piatos Ideenlehre, eine Einf?hrung 1903, the continuing 1921) justified what they considered philo of the Greek relevance above all philosophers, sophical by seeing in their writings the same central an itwas Greek

is precisely sues they identified in the works of Immanuel Kant. Anyone to reduce Greek philosophy to the who wished neither unique and unrepeatable personal it was produced nor under which or social circumstances for the to justify a claim

Plato, (though not exclusively) attempt to come to grips with

perennial validity of Greek philosophy by identifying itwith

a particular Idealistic stage in German somehow between obliged to try to mediate was philosophy these two hostile

94

HEIDEGGER'S

GREEKS

camps. For example, Julius Stenzel (Studien zur Entwicklung von Sokrates der platonischen Dialektik bis Aristoteles, bei Piaton und Aristoteles, 1917; Zahl und Gestalt 1924; Piaton der Erzieher, 1928) took great pains to reject explic both extreme positions, yet he himself found it difficult, if itly to present a philosophically not impossible, coherent picture of Plato which diverged radically from the general outlines of the Marburg school. in the 1920s without coming on the Marburg Neokantians and his followers on the im difficult, and perhaps was en canon, Heidegger instead on by concentrating in Germany to terms once and for all with other would have been To focus on Plato

the one hand and with Wilamowitz extremely Nietzsche's

possible. By adopting this dilemma abled to outflank

the Presocratics, whom and Wilam both the Neokantians owitz had largely neglected, but to whom many German clas sicists had been turning since the First World War. Thereby could seem simultaneously and nonconformist Heidegger fashionable. participating culture: he could Greek At the same time he could give the appearance of in a wider, not merely disciplinary intellectual rescue the Greeks philosophers the professors of from the professors of Phi from

and the Greek

losophy. in togas. Greeks are Germans 5. Heidegger's is typically Greek Heidegger of what Much ignores or sup or explains away: there is no slavery in Heidegger's presses no ath no heterosexuality, ancient Greece, no homosexuality,

letics, no war, no wine, no song, no anger, no laughter, no fear,

no superstition. focuses on those elements Instead, Heidegger like of the ancient Greeks that anticipate the values he would to adopt: reflectiveness, love of na receptivity, for their great poets and thinkers, sensitivity admiration ture, to their language, sometimes?depending upon the political (social and political struggle), at other circumstances?Kampf the Germans times Gelassenheit ger's Germans Insofar as Heideg (calm and resignation). are encouraged to model themselves upon the

Glenn W. Most

95

are Greeks in Lederhosen; Germans but Greeks, Heidegger's since Heidegger's Greeks are in fact an idealized projection of specifically German virtues and since all idealizations of the are ultimately in inspiration, Heidegger's Roman Greeks in togas. Greeks may be described as being Germans Greeks Heidegger's reason of their having that came are the first Europeans, not only by for everything good laid a foundation

after them, but also by reason of the bad tradi tions that they founded. What makes Heidegger's Greeks ul so German is that they already enact fully the timately from cjn?ai? to technology which all of Euro will go on to repeat on an ever larger scale. Al pean history and put it ready Plato and Aristotle betray Greek philosophy in the service of optimism, and Wissenschaft. reification, By falling away the time of the very earliest it is already almost thought, the central points adumbrated of Greek surviving documents too late. This had been one of

early philosophy, already in his Birth of Tragedy. For Nietzsche, clearly as for Heidegger, that means, for European history?and both thinkers, essentially German repeats, history?merely amplifies, and fulfills the Greek model. to propose If Heidegger the may be taken, therefore, at the same time Greeks as Germans, he may be understood to propose himself as Greek. He is keen to point out what he or Swabian prac takes to be affinities between Alemannian tices and language on the one hand, and Greek ones on the other. And his own peculiar style of writing?with its word its inven its exploration of etymological play, possibilities, tion of new words, especially by taking up ordinary words from every-day language sophical concepts?has the reader of his works upon their reader between Aristotle's and substantivizing them as philo of the same effect upon something in German as Aristotle's writings do (except for the obvious contrast

of Nietzsche's

in Greek extreme

no and Heidegger's brachylogy or not Aristotle less extreme prolixity). Whether served Hei as a model for his own style?it will be degger consciously recalled that the works of Aristotle were among the Greek

96

HEIDEGGER'S

GREEKS

texts the young Heidegger studied most intu intensely?my itive sense is that the experience of reading Heidegger in Ger man to that of reading is sometimes similar strikingly in Greek. Itmight be worth trying to provide the se Aristotle which linguistic documentation confirm or refute this intuition. 6. Heidegger's Greeks why they interest us. are not rious would be required to

the Greeks?that

is precisely

For the professional at there is almost nothing classicist, all of interest in Heidegger's work on Greek philosophy and no doubt says as much about professional poetry?which mains re about Heidegger. work Heidegger's to the classics profession, for except entirely marginal a very few classicists who are themselves largely marginal. in England and The professional study of ancient philosophy classicists France ancient phy, but largely ignores him; there are a few exceptions and Italy. There ismuch more interest in his work philosophy this has in on as it does

America

of philoso among German professors own influence been due to Heidegger's

in Germany of philosophy and seems upon the profession now to be dying out. That is, the reception of Heidegger's on Greek philosophy work among German philosophers not part of German forms part of German philosophy, clas between Heidegger and the classics pro sics; the antagonism he fostered has continued fession which after his death. Matters man in the professional study of Ger literature. For example, Heidegger's work on H?lderlin has strongly influenced H?lderlin studies, at least in reaction and not only against Heidegger, due in part to differences between fessional in Germany. This may be and pro the institutional are rather different

and elsewhere, between clas relation, in Germany on the one hand, and between German sics and philosophy on the other. studies and philosophy What

is interesting about Heidegger's is not that Greeks are Greeks, but that they are Germans and that they are they strik As Germans, they provide a particularly Heidegger's.

Glenn W. Most

97

(but now rapidly vanishing) ing example of the traditional German need for self-legitimation by appeal to the Greeks. at least three as This is a complex phenomenon, of which are particularly a deep discomfort with striking: a need for differentiation from the French model, modernity; which was based largely upon Rome; and the plurality of pects could not provide confessions, which meant that Christianity a solution, but only a set of problems. Heidegger tacitly pre a largely German Altertumswissen supposes professional schaft in his use of dictionaries; etymological in his evident hellenism world-historical cultures without editions, commentaries, he tacitly presupposes belief of that he need the ancient l?xica, and German Phil

privilege

only assert the Greeks over other

having to explain or defend it in detail; he a typically German and specifically Nietz tacitly presupposes schean nostalgia for origins in his no less evident belief that

he need only assert the superiority of the earlier Greeks over the later ones without having to explain or defend that in de tail either. In all these regards, Heidegger is an absolutely typ ical German thinker, different from others if at all only in the extremity of some of his positions. distinguishes Heidegger most significantly from many of the other representatives of German Philhellenism since the What end of the eighteenth century is the passionate intensity of his in the ancient Greek texts and his ability to com absorption municate this intensity to many readers, especially to those with Their with little or no knowledge of ancient with Greek themselves. patience extraordinary his lengthy and obscure testimony to the power of the ancient Greeks, however medi ated, to fascinate readers even in our own century. Most classicists ignore Heidegger; him. That ismistaken. as they have be partly his merit. the few who so much tone and his moralizing is a remarkable interpretations

tend to deplore ably survive Heidegger, they do, that will

do not, The Greeks will prob else. And if

98

HEIDEGGER'S

GREEKS

NOTE

on 20 April 2001 is a revised version of a lecture delivered at a meeting of the Bay Area Heidegger University Colloquium; H.-U. It has Gumbrecht. my thanks to my hosts and audience, especially from the criticisms of A. Davidson, benefited further B. and suggestions i. This article at Stanford and I.Wienand; my thanks to them all. All ref Full, R. Pippin, M. V?hler, are to the Gesamtausgabe, erences to Heidegger's writings hrsg. von F.-W. as GA with von Herrmann a.M. the volume indicated (Frankfurt 1975-), as indicated and page number, (Frankfurt a.M. 1950), except for Holzwege H with cated indi and Was hei?t Denken? the page number, 1954), (T?bingen are my own. as WhD I have with the page number. All translations a scholarly but for chosen not to burden these six theses with apparatus; of parts of the fourth the and further elaboration documentation thesis, reader is referred 35 to my (1989), articles 1-23, Po?tica "Zur Arch?ologie "Schlegel, Schlegel der Archaik," Antike und eines und die Geburt "Il?teuoc Jahre," rc?vx?ov in Alter

Abendland

Trag?dienparadigmas," Ttarrip. Die Vorsokratiker tumswissenschaft as well 87-114, zsches Erfindung philosophische and Schlegel

in den

and 155-75, 25 (1993) in der Forschung der Zwanziger 20er ]ahren, ed. H. Flashar

as to the following der Vorsokratiker."

Bd. Tradition, Ro Damnatio of Euripides," the Nineteenth-Century Greek, man and Byzantine "The Last of A. Henrichs, Studies 27 (1986), 335-67; of Euripides," Condemnation Friedrich Nietzsche's the Detractors: Greek, and Byzantine Studies 27 (1986), Roman 369-97.

1995), (Stuttgart "Niet studies: T. Borsche, important in J. Simon und die (Hrsg.), Nietzsche I (W?rzburg E. Behler, "A. W. 1985), 62-87;

También podría gustarte

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Technology Procurement HandbookDocumento329 páginasThe Technology Procurement HandbookAlexander Jose Chacin NavarroAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Admission: North South University (NSU) Question Bank Summer 2019Documento10 páginasAdmission: North South University (NSU) Question Bank Summer 2019Mahmoud Hasan100% (7)

- Taschen Catalogue 2013 NEW TitlesDocumento237 páginasTaschen Catalogue 2013 NEW Titlesdovescry100% (3)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Make Yeast StarterDocumento2 páginasMake Yeast StarterAlexandraAún no hay calificaciones

- Money Order Sauce.Documento2 páginasMoney Order Sauce.randomAún no hay calificaciones

- 1988 Mazda 323 Workshop Manual V1.0 (Turbo Only)Documento880 páginas1988 Mazda 323 Workshop Manual V1.0 (Turbo Only)Mike Marquez100% (2)

- Finding Targets PDFDocumento9 páginasFinding Targets PDFSteve TangAún no hay calificaciones

- Auls e Brook 2018Documento17 páginasAuls e Brook 2018dovescry100% (1)

- Odhgos Syntaxeos Episthmonikon Keimenon SDocumento12 páginasOdhgos Syntaxeos Episthmonikon Keimenon SdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Romankiewicz-2018-Oxford Journal of ArchaeologyDocumento15 páginasRomankiewicz-2018-Oxford Journal of ArchaeologydovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Ann Killebrew Mycenaean Objects in The LevantDocumento14 páginasAnn Killebrew Mycenaean Objects in The LevantdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- MARINA FISCHER The Hetaira's KalathosDocumento20 páginasMARINA FISCHER The Hetaira's KalathosdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- A Model of An Ancient Greek Loom A Model of An Ancient Greek LoomDocumento2 páginasA Model of An Ancient Greek Loom A Model of An Ancient Greek LoomdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Ann Killebrew Mycenaean Objects in The LevantDocumento14 páginasAnn Killebrew Mycenaean Objects in The LevantdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Kinet Hoyuk Middle and Late IA CeramicsDocumento28 páginasKinet Hoyuk Middle and Late IA CeramicsdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Pindar and The Prostitutes, Leslie KurkeDocumento28 páginasPindar and The Prostitutes, Leslie Kurkedovescry100% (2)

- Arcane DB GettingStartedDocumento12 páginasArcane DB GettingStarteddovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Athens 803 and The EkphoraDocumento18 páginasAthens 803 and The EkphoradovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Orson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchDocumento41 páginasOrson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Transport Stirrup Jars From Israel: Online Publications: AppendixDocumento7 páginasTransport Stirrup Jars From Israel: Online Publications: AppendixdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- 15 ThesisDocumento240 páginas15 Thesiscalacta100% (1)

- The American School of Classical Studies at AthensDocumento3 páginasThe American School of Classical Studies at AthensdovescryAún no hay calificaciones

- Joshua Wolf ShenkDocumento3 páginasJoshua Wolf Shenkdovescry100% (1)

- Flow Through A Converging-Diverging Tube and Its Implications in Occlusive Vascular Disease-IDocumento9 páginasFlow Through A Converging-Diverging Tube and Its Implications in Occlusive Vascular Disease-IRukhsarAhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- A New Procedure For Generalized Star Modeling Using Iacm ApproachDocumento15 páginasA New Procedure For Generalized Star Modeling Using Iacm ApproachEdom LazarAún no hay calificaciones

- EXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Documento5 páginasEXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Bendo Marjorie P.100% (1)

- Cross Border Data Transfer Consent Form - DecemberDocumento3 páginasCross Border Data Transfer Consent Form - DecemberFIDELIS MUSEMBIAún no hay calificaciones

- Naca Duct RMDocumento47 páginasNaca Duct RMGaurav GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Most Dangerous City - Mainstreet/Postmedia PollDocumento35 páginasMost Dangerous City - Mainstreet/Postmedia PollTessa VanderhartAún no hay calificaciones

- I. Objectives Ii. Content Iii. Learning ResourcesDocumento13 páginasI. Objectives Ii. Content Iii. Learning ResourcesZenia CapalacAún no hay calificaciones

- 1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsDocumento51 páginas1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsUddipta Bharali100% (1)

- Summative Test in Foundation of Social StudiesDocumento2 páginasSummative Test in Foundation of Social StudiesJane FajelAún no hay calificaciones

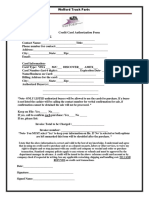

- Credit Card Authorization Form WoffordDocumento1 páginaCredit Card Authorization Form WoffordRaúl Enmanuel Capellan PeñaAún no hay calificaciones

- TinkerPlots Help PDFDocumento104 páginasTinkerPlots Help PDFJames 23fAún no hay calificaciones

- Evidence MODULE 1 Evidence DefinitionDocumento8 páginasEvidence MODULE 1 Evidence Definitiondave BarretoAún no hay calificaciones

- NiftDocumento3 páginasNiftMegha Nair PillaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Drilling Jigs Italiana FerramentaDocumento34 páginasDrilling Jigs Italiana FerramentaOliver Augusto Fuentes LópezAún no hay calificaciones

- Cimo Guide 2014 en I 3Documento36 páginasCimo Guide 2014 en I 3lakisAún no hay calificaciones

- Romano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)Documento7 páginasRomano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)ទី ទីAún no hay calificaciones

- Permanent Magnet Motor Surface Drive System: Maximize Safety and Energy Efficiency of Progressing Cavity Pumps (PCPS)Documento2 páginasPermanent Magnet Motor Surface Drive System: Maximize Safety and Energy Efficiency of Progressing Cavity Pumps (PCPS)Carla Ayelen Chorolque BorgesAún no hay calificaciones

- 8051 Programs Using Kit: Exp No: Date: Arithmetic Operations Using 8051Documento16 páginas8051 Programs Using Kit: Exp No: Date: Arithmetic Operations Using 8051Gajalakshmi AshokAún no hay calificaciones

- Analysis Chart - Julie Taymor-ArticleDocumento3 páginasAnalysis Chart - Julie Taymor-ArticlePATRICIO PALENCIAAún no hay calificaciones

- Auto CadDocumento67 páginasAuto CadkltowerAún no hay calificaciones

- Green ThumbDocumento2 páginasGreen ThumbScarlet Sofia Colmenares VargasAún no hay calificaciones

- تأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFDocumento36 páginasتأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFSofiane DouifiAún no hay calificaciones

- Be and Words From The List.: 6B Judging by Appearance Listening and ReadingDocumento3 páginasBe and Words From The List.: 6B Judging by Appearance Listening and ReadingVale MontoyaAún no hay calificaciones

- KSP Solutibilty Practice ProblemsDocumento22 páginasKSP Solutibilty Practice ProblemsRohan BhatiaAún no hay calificaciones