Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Sociometric Popularity Versus Perceived Popularity

Cargado por

api-81111185Descripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Sociometric Popularity Versus Perceived Popularity

Cargado por

api-81111185Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

Understanding Popularity in the Peer System Author(s): Antonius H. N. Cillessen and Amanda J.

Rose Reviewed work(s): Source: Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 2005), pp. 102-105 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of Association for Psychological Science Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182997 . Accessed: 02/06/2012 23:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and Association for Psychological Science are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Current Directions in Psychological Science.

http://www.jstor.org

CURRENT DIRECTIONS

IN PSYCHOLOGICAL

SCIENCE

Understanding Peer

Antonius University H.N.

Popularity

in

the

System

Cillessen and Amanda and University J. Rose of Missouri-Columbia of Connecticut

ABSTRACT?Much rejected cluding problems. by peers; aggression; Recently,

research who and

has engage who

focused

on

youth

who

are in

in negative are at risk for

behavior, adjustment increasingly

researchers

have

become

For example, consider the profiles of two eighth graders, Tim and Jason. Tim iswell liked by his peers. He is genuinely nice to others and helps out when needed. Tim is athletic but does not use his physical abilities to aggress against others. In fact, Tim

tends to avoid even verbal confrontations when possible, pre

interested

tween two

in high-status

groups of

youth. A distinction

high-status youth: those

is made

who

be

are

genuinely

dominantly

well

liked by their peers

behaviors and

and

those

engage

who are

in pre

seen as

prosocial

to find prosocial ways of solving conflicts. ferring with Tim, Jason is better known by his classmates but Compared he is not necessarily well liked. Even peers who do not know instead

him personally know who he is. Many of Jason's classmates

by their peers but are not necessarily well liked. popular The latter group of youth is well known, socially central, as and emulated, but displays a mixed profile of prosocial

well now these as aggressive to and address and Of manipulative the their distinctive developmental interest are behaviors. Research of and and needs characteristics precursors high-status

imitate his style of dress and taste inmusic and would like to be better friends with him so they could be part of the in-crowd.

Jason when his can be very nice to other kids but can also intimidate situations them to provoked advantage. Developmental psychologists know a fair amount about youth or angry, or can manipulate social

two groups

consequences.

particular

aggressors impact powerful peers. The heterogeneity of high-status youth complicates the understanding of the peer of the social dynamics new and important insights into the group, but will lead to socially developmental

KEYWORDS?peer

and

their

on

their

like Tim. Youth who are well liked by others are categorized by

peer-relations researchers as sociometrically popular. Socio

significance

relations;

of peer

popularity;

relationships.

social status

metrically popular youth generally display high levels of pro social and cooperative behavior and low levels of aggression (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998). But although develop

mentalists not the would type refer to Tim most think known, as youth of sociometrically would popular consider peers central, of person They well he is popular, one of their as and those who,

"popular" Developmental social and structure adolescence. psychologists and Peer dynamics status continue of is an to be interested in the like Jason,

peers. are

socially

emulated

the peer important research with

group

in childhood in their driven status, by who a

(Adler & Adler,

have begun as to study perceived to them ular. have

1998).

more popular,

In recent

seriously rather that to

years,

youth than

developmentalists

like Jason, referring pop youth youth aspire

construct has been social be

research. concern operate as

In the past, for children at the As fringe

much and

of this adolescents

sociometrically

low

Although aggressive

evidence traits

suggests in addition

perceived-popular ones,

of the peer much

system has been

and may learned

categorized the ori

prosocial

rejected.

a result,

about

gins of peer rejection and its effects on development

Coie, ingly 1990). interested More recently, in peer-group high-status researchers members and have with become high social

(Asher &

increas status. form a

to be popular like Jason more than they aspire to be like Tim it is important to consider (Adler & Adler, 1998). Accordingly,

seriously the meaning and function of these divergent forms

of popularity.

In this similar Specifically, article, to and we we consider from (a) how perceived-popular popular and youth are different discuss: sociometrically the conceptualization youth. meas

Interestingly, uniform group.

children

adolescents

do not

urement of sociometric

Address correspondence to Antonius H.N. CiUessen, of Department Rd., U-1020, behavior of sociometrically (c) the adjustment outlining important

and perceived

and for the

popularity,

We

(b) the social

youth, conclude and by

perceived-popular two groups.

University Psychology, CT 06269-1020; Storrs,

406 Babbidge of Connecticut, e-mail: antonius.ciUessen@uconn.edu.

outcomes directions

for future

research.

102 Copyright ?

2005 American Psychological Society

Volume 14?Number 2

Antonius

H.N.

CiUessen

and Amanda

J. Rose

SOCIOMETRIC VERSUS PERCEIVEDPOPULARITY

Traditionally, the study of peer relations has focused on socio metric status, how well liked (or rejected) youth are by their peers (Asher & Coie, 1990; Coie & CiUessen, 1993). Several

decades adjustment of research correlates have of provided sociometric data on status the behavioral (Kupersmidt and &

associate

a mixture

of prosocial

and

antisocial

traits

and

be

haviors with perceived popularity. Although there is overlap between sociometric and perceived

popularity, the constructs are not redundant (LaFontana &

CiUessen, 2002; Rose et al., 2004). Consider one study that employed a categorical approach to identify sociometrically youth (Parkhurst & Hopmeyer, popular and perceived-popular 1998). Only 36% of sociometrically popular students were also students perceived popular, and only 29% of perceived-popular

were between differences popular and also sociometrically the two constructs the popular. There is enough similarities of distinction as well as to determine characteristics youth.

Dodge,

2004). This research provides a crucial foundation for

peer relations. have begun to examine perceived researchers

understanding Recently,

popularity as a unique but equally important dimension. Edu cational sociologists have long recognized the social power

(influence over others) of perceived-popular youth as evidenced

between

sociometrically

perceived-popular

by qualitative descriptions of them by their peers (Adler & Adler, 1998; Eder, 1985). Only in the past 5 to 10 years have

researchers tative methods. popularity in which is usually participants assessed are with asked a peer-nom to name the begun to study perceived popularity with quanti

BEHAVIORAL PROFILES

Research and profiles of sociometrically has revealed similarities and differ youth perceived-popular ences. Both kinds of youth are found to be prosocial and co

operative. score very However, whereas sociometrically perceived (see Rubin popularity et al., 1998, popular youth low on aggression, with aggression is positively for a review

on the behavioral

Sociometric ination procedure,

peers

nations size

in their grade who they like most and like least. Nomi

for each question are are counted and adjusted grades (Coie, for grade so that the data comparable across Dodge,

associated

& Coppotelli,

represented ence) minus calculated

1982). Sociometric

with a score by using on

popularity for each person is

scale (social prefer of liked-most nominations received. may

of the behavioral profiles of sociometrically

In quantitative lates and with behavior, studies on how perceived have typically Overt researchers

popular youth).

popularity measured corre overt refers to

a continuous

the number

the number

of liked-least than using

nominations such scores,

he or she

relational

aggression

separately.

aggression

Alternatively,

rather

researchers

a categorical approach and identify sociometrically popular youth as those with many liked-most and few liked-least employ

nominations. In early qualitative research, educational sociologists using

physical assaults and direct verbal abuse. Relational aggression is aimed at damaging relationships and includes behaviors such

as ignoring or excluding a person and spreading rumors (Crick

& Grotpeter, 1995). Both overt and relational aggression are related to perceived popularity. For example, Parkhurst and Hopmeyer

but not

ethnographic

simply

methods

which

identified perceived-popular

classmates were referred to as

youth by

popular

(1998) found that youth who were perceived popular

popular were overtly aggressive. Rod

observing

sociometrically

by their peers

quantitative derived see from

(Adler & Adler,

however, nominations and who

1998; Eder,

perceived (i.e.,

1985).

name popular;

In recent

has who been they

studies, peer popular

popularity

participants as least

kin, Farmer, Pearl, (2000) empirically dis criminated a subgroup of "model" popular youth with high scores for affiliative (e.g., friendly) behaviors and low scores for

overt high aggression scores from a subgroup of "tough" and average and popular scores relational was youth with for overt Studies and aggression in which in which both for affiliative aggression measured of

and Van Acker

as most

they

see

CiUessen

& Mayeux,

Hopmeyer, continuous from

2004; LaFontana & CiUessen,

1998; scale Rose, of Swenson, perceived & Waller, popularity nominations nominations. categorical

2002; Parkhurst &

2004). have Scores been on a derived of stud identi

behavior. were

overt

assessed

perceived demonstrated

popularity positive

the number

of most-popular least-popular taken a

or the number In other and

as a continuous

variable

associations

most-popular ies, researchers

minus have

approach

& CiUessen,

Why

both forms of aggression with perceived 2002; Rose et al., 2004).

would presumably aversive

popularity

(LaFontana

be

fied youth with high perceived

most-popular Interestingly, the recent with on nominations in neither quantitative an a priori the and

popularity

few

as those with many

nominations. research provide rather, nor

aggressive

behaviors

least-popular ethnographic researchers

associated with high status as indicated by perceived

ity? It may be that some children when or adolescents publicly for social use in certain re certain to situations people (e.g., (e.g., provoked) status)

popular

aggression or against

original did

studies definition intuitive have to begun

partic they

ipants lied

of popularity; understanding to map

competitors perceived may use

strategically For example, aggression who this in some idea, a

the participants' researchers ascribe

of the concept. children provid

achieve

or maintain youth and their deter social

popularity. overt or relational youth

Recently, and

the meanings again without

perceived-popular to intimidate way threaten

adolescents

"popularity,"

competitors standing.

or other Consistent

ing an a priori definition

Findings from these studies

(e.g., LaFontana & CiUessen,

show that children and

2002).

with

adolescents

study by Vaillancourt, Hymel,

and McDougall

(2003) revealed

Volume 14?Number

2 103

Lnderstanding

Popularity

in the Peer

System

an

association

between

bullying youth prosocial

and use a

perceived strategic

popularity. combination peers

Mayeux, through

2004), nine. As

but can

the be

pattern seen

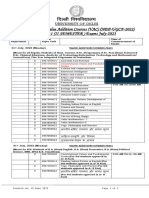

was in Figure

similar

across

grades aggression

six

Moreover, of both

perceived-popular aggressive and

1, relational

behaviors

to manipulate

in ways that result in high status (Hawley, 2003). Recent longitudinal research supports the hypothesis

some ceived important youth deliberately This act aggressively also relational to enhance suggests an their popularity. association research between especially and

was positively associated with perceived popularity for both boys and girls but was a particularly strong predictor of high

status for girls.

that

per

aggression

per

OUTCOMES ADJUSTMENT

An ences important with reason peers much with may for studying be predictive has peer relations of personal how research is that experi

ceived popularity.

Mayeux, strongly 2004), related to

In a 5-year longitudinal

relational later aggression perceived was popularity

study (CiUessen &

found than to be was more overt

adjustment. sociometric consistently

aggression.

that ceived Overt cause acts. relational

Similarly, another study (Rose et al., 2004)

aggression 6 months may display relational social be was more later related dominance aggression power. For than to strongly was related overt

found

to per

Accordingly, status correlates

research adjustment,

addressed and the

popularity aggression youth However, can

aggression. be

perceived through

popularity overtly aggressive

popularity is predictive of positive both concurrently and in the future (Rubin et al., adjustment 1998). For example, sociometrically popular youth tend to be well adjusted emotionally and to have high-quality friendships. less is known about the adjustment of per Considerably

ceived-popular in the peer hand, because would are youth. group Previous to research on status expectations. with problems hand, because behavior and On behavior the one in leads opposing

indicates

that sociometric

may example,

be

especially by

effective ex

for managing

selectively

cluding others, youth may influence who is in the popular crowd

and other rumors, keep out those who threaten their social status. such and Engaging as spreading the relationally affords one aggressive a degree behaviors, of anonymity

aggression similar On

is associated behavior the other

problems, youth status in

therefore

one who

expect aggressive.

for popular high

opportunity

appearance Research sion and

to strategically

of being further mean. indicates popularity we found

hurt other people while hiding the

that may the relation vary by between age and between aggres gender. overt

the peer group is associated with being well adjusted, one would expect that perceived popularity, even if achieved through ag

gressive limited means, evidence is associated available perceived without with time positive seems has negative adjustment. to favor immediate The at this the second rewards

perceived

In our

research,

positive

associations

and relational

15-year-old

aggression

and perceived

(grades 6?9), but

popularity

not in 9to

in 12- to

11-year

expectation?that (Hawley, 2003)

popularity concurrent

adolescents

consequences

(grades 3-5). This shift coincided with the transi tion from elementary school to middle school and may have been due to the fact that the social skills required to act aggres sively in ways that lead to high status are complex and develop

with We age also (LaFontana found that & the CiUessen, link 2002; Rose relational et al., 2004). and between aggression

old children

(Rodkin et al., 2000). Hawley's

mixture havior of prosocial makes youth behavior effective at

(2003) research indicates that a

and coercive what or they aggressive want be getting in social

contexts. And the tough popular youth identified by Rodkin and

his such may colleagues as be depression reconciled benefits peer group, beyond we hypothesize may be (2000) or did not demonstrate The elevated symptoms, expectations aggressive context of their of youth the ad anxiety. contradictory and social in terms

perceived popularity was stronger for girls than for boys (Cil lessen & Mayeux, 2004; Rose et al., 2004). Figure 1 illustrates this finding for data collected in eighth grade (CiUessen &

if perceived-popular in the but pay immediate a price

experience olescent adjustment Thus, term

long-term

adolescence. that for perceived-popular combined with long-term youth, short

advantages

disadvan

tages. Establishing

follow-up studies

whether

of such

this is true will require long-term

youth. Just as there are tough and

model high-status subgroups (Rodkin et al., 2000), there may be two diverging developmental paths that popular youth follow

into young adulthood. In one path, perceived-popular youth may

continue to be influential and serve in leadership

peer and Low Average Relational Aggression High have groups. successful different In the other, when reward they they may move no into and longer new different be social

roles in later

central that social contexts for

socially

structures

criteria

prominence. Which

may depend delicate balance

of these two pathways an individual follows

he or she prosocial is able and to strike the optimal, be between Machiavellian

Fig. 1. Perceived popularity and high levels of relational

of girls and boys who exhibit low, average, 2004). (CiUessen & Mayeux, aggression

on whether

104 Volume 14?Number

Antonius

H.N.

CiUessen

and Amanda

J. Rose

haviors, new

to

gain

both

social

preference how this

as well balance may

as

influence be achieved

in

REFERENCES

Adler, P.A., & Adler, identity. Asher, New P. (1998). Peer power: Pr?adolescent University Press. New York: culture and

groups.

Discovering

developmentally

in later life is an

and how itmay affect what pathway is followed

exciting avenue for future research.

Brunswick, J.D.

NJ: Rutgers

S.R., & Coie, Cambridge

University

(1990). Peer Press.

rejection

in childhood.

CONCLUSIONS

Decades of research on sociometric popularity have produced

L. (2004). From censure & Mayeux, CiUessen, A.H.N., ment: in the association changes Developmental and social status. Child Development, 75, gression Coie, effects J.D., & CiUessen, on children's Science, A.H.N. (1993). Peer Current rejection: Directions

to reinforce between 147-163. and Origins in Psycho and ag

consistent

plication.

and important findings with potential practical

Recent research suggests that the complex

ap

Coie,

logical

development. 2, 89-92. H.

construct

of perceived

search. mental Given

popularity needs

all that is known

to be incorporated

about the negative researchers

into this re

develop to learn Crick, need

J.D., Dodge, K.A., & Coppotelli, status: A cross-age of social chology, N.R., and 18, 557-570. & Grotpeter, J.K.

(1982).

Dimensions Developmental

types Psy

perspective.

consequences

of aggression,

(1995).

Relational Child

aggression, Development, relations 154-165.

gender, 66,

why aggression perceived

whether

leads to high status in the form of popularity. Moreover, it will be important to learn sometimes

perceived-popular youth are on a positive or

social-psychological 710-722. Eder,

adjustment.

aggressive

D. (1985). The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal female adolescents. 58, Sociology of Education,

among

trajectory. Although they seem to negative developmental benefit in the short term in the immediate social context of the

peer status group, and the behavior also longer-term are must not yet outcomes known. about the impact of perceived associated with their

of resource P.H. (2003). Prosocial and coercive Hawley, configurations A case for the well-adapted in early adolescence: Mach control 279-309. iavellian. Merrill-Palmer 49, Quarterly, J.B., & Dodge, Kupersmidt, tions: From development American LaFontana, Psychological & CiUessen, and unpopular A.G. K.A. peer (Eds.). (2004). Children's to intervention to policy. Washington, Association. A.H.N. peers: 38, (2002). Children's A multi-method rela DC:

Researchers

learn

popular aggressors on the development

peers. them. Of The particular negative when can the concern consequences aggressor engage are youth

and adjustment of their

who are victimized may and in the may be by ex

K.M.,

of popular Developmental Parkhurst,

stereotypes assessment.

of victimization is socially other central people youth behavior are among

Psychology,

635-647. and popularity of peer status.

acerbated and tion. the

powerful victimiza influence

J.T., & Hopmeyer, popularity:

therefore

easily

peer-perceived Journal Rodkin, P.C., of Early Farmer,

(1998). Sociometric Two distinct dimensions 18, 125-144.

Adolescence, T.W., Pearl, boys:

Furthermore, development of

perceived-popular antisocial youth may disperse

their their

R., & Van Acker, Antisocial 36, E.M. and 14-24. (2004). Overt

R.

(2000).

Het

peers.

Because or risky

perceived-popular behaviors

emulated, through

antisocial group Rose,

erogeneity tions. Developmental A.J., Swenson,

of popular

prosocial

configura

Psychology,

the

peer

L.P., & Waller,

and relational differences Psychol

especially

larity in

quickly. Clearly,

the peer context

the function and impact of popu

are complex; learning more

about these processes will be challenging, but will yield im portant new insights into the social dynamics of peer groups

across the life span.

and perceived Developmental popularity: aggression in concurrent relations. and prospective Developmental ogy, 40, 378-387. Rubin, K.H., Bukowski, and W.M.,

relationships,

(Vol. Ed.), senberg and personality emotional, New York: Wiley. Vaillancourt, (See References) (See References) (Eds.). (2004). (See References) Elias zation 176). T., Hymel, for Implications & J.E. Zins

& Parker, J.G. (1998). Peer interactions, In W. Damon groups. (Series Ed.) & N. Ei Vol. 3. Social, Handbook of child psychology: development (5th ed., pp. 619-700).

Recommended Adler, Asher,

Reading P.A., & Adler, P. (1998). S.R., & Coie, J.D. (1990). K.A.

P. (2003). Bullying is power: S., & McDougall, In M.J. intervention school-based strategies. and victimi peer harassment, (Eds.), Bullying, The next generation Press. of prevention (pp. 157

Kupersmidt,

J.B., & Dodge,

in the schools: New

York: Haworth

Volume 14?Number

2 105

También podría gustarte

- Parenting A Teen Girl: A Crash Course On Conflict, Communication & Connection With Your Teenage DaughterDocumento11 páginasParenting A Teen Girl: A Crash Course On Conflict, Communication & Connection With Your Teenage DaughterNew Harbinger Publications100% (6)

- Self Hypnosis: Hypnosis and The Unconscious MindDocumento6 páginasSelf Hypnosis: Hypnosis and The Unconscious MindSai BhaskarAún no hay calificaciones

- LGBT in SHS - RevisedDocumento14 páginasLGBT in SHS - RevisedJam CandolesasAún no hay calificaciones

- Universities Institutions That Accept Electronic Scores StedDocumento52 páginasUniversities Institutions That Accept Electronic Scores StedPallepatiShirishRao100% (1)

- Self-Report Interpersonal Representation StructureDocumento6 páginasSelf-Report Interpersonal Representation Structuresneha0% (1)

- Research Final PaperDocumento20 páginasResearch Final PaperJohn Carl AparicioAún no hay calificaciones

- O Levels Maths Intro BookDocumento2 páginasO Levels Maths Intro BookEngnrXaifQureshi0% (1)

- Attitudes Towards LGBTDocumento18 páginasAttitudes Towards LGBTpaul william lalataAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Potency - Exploring Phenomenon of Potency in Osteopathy in The Cranial Field - Helen Harrison - Research ProjectDocumento105 páginasWhat Is Potency - Exploring Phenomenon of Potency in Osteopathy in The Cranial Field - Helen Harrison - Research ProjectTito Alho100% (1)

- National Emergency Medicine Board Review CourseDocumento1 páginaNational Emergency Medicine Board Review CourseJayaraj Mymbilly BalakrishnanAún no hay calificaciones

- Practical Research 11 Humss C ArcelingayosoliventapiceriaDocumento21 páginasPractical Research 11 Humss C Arcelingayosoliventapiceriakai asuncionAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Study HistoryDocumento1 páginaWhy Study Historyregine_liAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment On SociometryDocumento9 páginasAssignment On SociometryPriya88% (8)

- Seminar On SociometryDocumento9 páginasSeminar On SociometryPriya100% (1)

- Cillessen and Rose (2006)Documento5 páginasCillessen and Rose (2006)Karl Justine DangananAún no hay calificaciones

- Background of The StudyDocumento41 páginasBackground of The StudyTristan Lim100% (1)

- Perilaku Prososial Sebagai Prediktor Status Teman Sebaya Pada RemajaDocumento9 páginasPerilaku Prososial Sebagai Prediktor Status Teman Sebaya Pada RemajaMemet GoAún no hay calificaciones

- Bachelor of Elementary Education Course CodeDocumento8 páginasBachelor of Elementary Education Course CodeAjie Kesuma YudhaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Social and Psychological Characteristics of NoDocumento26 páginasThe Social and Psychological Characteristics of NoLarisa - Maria BărnuțAún no hay calificaciones

- Perilaku Prososial Sebagai Prediktor Status Teman Sebaya Pada RemajaDocumento9 páginasPerilaku Prososial Sebagai Prediktor Status Teman Sebaya Pada RemajaMemet GoAún no hay calificaciones

- Manuscript Gomila Paluck Preprint Forthcoming JSPP Deviance From Social Norms Who Are The DeviantsDocumento48 páginasManuscript Gomila Paluck Preprint Forthcoming JSPP Deviance From Social Norms Who Are The DeviantstpAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 1 NeeewDocumento8 páginasChapter 1 NeeewAnonymous enspv0UpAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Intelligence and Academic Achievement As Predictors of Adolescent PopularityDocumento11 páginasSocial Intelligence and Academic Achievement As Predictors of Adolescent PopularityAndy BarriosAún no hay calificaciones

- Peer Group InfluenceDocumento17 páginasPeer Group InfluenceCharls John ErcilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis For DefenseDocumento36 páginasThesis For DefenseKuya OinkoinkAún no hay calificaciones

- Friendship Goals Understanding The Influence of Peer Pressure On Teenagers' Social BehaviorDocumento11 páginasFriendship Goals Understanding The Influence of Peer Pressure On Teenagers' Social BehaviorFrancine Isabel R. PastoralAún no hay calificaciones

- AbstractDocumento12 páginasAbstractLưu Lê Minh HạAún no hay calificaciones

- Personal Characteristics ProposalDocumento6 páginasPersonal Characteristics ProposalBrian OduorAún no hay calificaciones

- Dsalazar Finaldraft1Documento12 páginasDsalazar Finaldraft1api-302701877Aún no hay calificaciones

- Role ModelsDocumento18 páginasRole ModelsAnithaAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis About Peer InfluenceDocumento6 páginasThesis About Peer Influencerhondacolemansavannah100% (2)

- GQ 7 ZRRBV RHW 9 M V19 PWXXK SRVQQ LNIm Iy 0 L Z9 N UFfDocumento9 páginasGQ 7 ZRRBV RHW 9 M V19 PWXXK SRVQQ LNIm Iy 0 L Z9 N UFfNgô Thu NgânAún no hay calificaciones

- BullyingDocumento5 páginasBullyingAudrey Mae EsguerraAún no hay calificaciones

- Belonging To and Exclusion From The Peer Group in Schools: Influences On Adolescents' Moral ChoicesDocumento21 páginasBelonging To and Exclusion From The Peer Group in Schools: Influences On Adolescents' Moral ChoicesRoxana ElenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Stereotypes Affects On Child Development-3Documento18 páginasStereotypes Affects On Child Development-3api-317501645Aún no hay calificaciones

- Taenang Reaserch ToDocumento16 páginasTaenang Reaserch Toyeth blytAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: Social Support On Relationships 1Documento7 páginasRunning Head: Social Support On Relationships 1brianAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Changes and Peer Group Influences Among AdolescentsDocumento5 páginasSocial Changes and Peer Group Influences Among AdolescentsIlango PonnuswamiAún no hay calificaciones

- Reyes Et Al 2023Documento21 páginasReyes Et Al 2023Martin Radley Navarro-LunaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 123Documento32 páginasChapter 123janecortezdesabille08Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research About SogieDocumento22 páginasResearch About SogieGold PanuelosAún no hay calificaciones

- Exploring The Parenting Management StylesDocumento13 páginasExploring The Parenting Management StylesAnonymous BL2sKidoAún no hay calificaciones

- Gender RolesDocumento20 páginasGender RolesYolo MeAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of Discrimination On Self-Esteem in LGBTQ+ Community in San Agustin Is Institute of TechnologyDocumento32 páginasThe Impact of Discrimination On Self-Esteem in LGBTQ+ Community in San Agustin Is Institute of Technologychristopher layupanAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction For A Research Paper On BullyingDocumento4 páginasIntroduction For A Research Paper On Bullyingxvrdskrif100% (1)

- The Bedan Journal of Psychology 2013Documento312 páginasThe Bedan Journal of Psychology 2013San Beda Alabang100% (5)

- Chapter 2Documento6 páginasChapter 2maxinevectorlampsAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis Title About Social BehaviorDocumento5 páginasThesis Title About Social Behaviorsamantharossomaha100% (2)

- Effects of Social Support On Self EsteemDocumento7 páginasEffects of Social Support On Self Esteemanusha shankarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effects of Social Media On Modern Gender Roles Among The Students of BSEntrep in QCUDocumento20 páginasThe Effects of Social Media On Modern Gender Roles Among The Students of BSEntrep in QCURechelle Ann GamoAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Comparison, Materialism, and Compulsive Buying Based On Stimulus Response-ModelDocumento17 páginasSocial Comparison, Materialism, and Compulsive Buying Based On Stimulus Response-ModelNouman AhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- Holism, Contextual Variability, and The Study of Friendships in Adolescent DevelopmentDocumento17 páginasHolism, Contextual Variability, and The Study of Friendships in Adolescent DevelopmentonecolorAún no hay calificaciones

- Peer Pressure and Self - Confidence Among Senior High School Students of The University of The Immaculate ConceptionDocumento17 páginasPeer Pressure and Self - Confidence Among Senior High School Students of The University of The Immaculate ConceptionLuna AndraAún no hay calificaciones

- 10 Literature ReviewDocumento11 páginas10 Literature ReviewJazz EsquejoAún no hay calificaciones

- FinalDocumento8 páginasFinalTOLING, PETER NICHOLAS N.Aún no hay calificaciones

- People Who Have Similar Characters or Interests, Especially Ones of Which You Disapprove, and Who Often Spend Time With Each OtherDocumento11 páginasPeople Who Have Similar Characters or Interests, Especially Ones of Which You Disapprove, and Who Often Spend Time With Each OtherKenshin paul GuintoAún no hay calificaciones

- Homosexuality, Social Belongingness and Mental HealthDocumento3 páginasHomosexuality, Social Belongingness and Mental HealthbroncoAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Research StudyDocumento18 páginasSocial Research StudyAli RungeAún no hay calificaciones

- Background of The StudyDocumento15 páginasBackground of The Studyerynharvey.corpuzAún no hay calificaciones

- Approved Title ResearchDocumento3 páginasApproved Title ResearchZeri GutierrezAún no hay calificaciones

- Psychology AssignmentDocumento12 páginasPsychology AssignmentPrince Hiwot EthiopiaAún no hay calificaciones

- RESEARCH 2022 - 2023WPS OfficeDocumento11 páginasRESEARCH 2022 - 2023WPS OfficeAshlee Talento100% (1)

- Research ScriptDocumento3 páginasResearch ScriptDenisse AtienzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Support Self Esteem 2Documento3 páginasSocial Support Self Esteem 2anusha shankarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Correlation of Social Anxiety Towards The Behaviour of Grade 12 Students in SJDM Cornerstone College Inc.Documento47 páginasThe Correlation of Social Anxiety Towards The Behaviour of Grade 12 Students in SJDM Cornerstone College Inc.Mark The PainterAún no hay calificaciones

- Organized Out-of-School Activities: Setting for Peer Relationships: New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, Number 140De EverandOrganized Out-of-School Activities: Setting for Peer Relationships: New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, Number 140Jennifer A. FredricksAún no hay calificaciones

- Saveetha EngineeringDocumento3 páginasSaveetha Engineeringshanjuneo17Aún no hay calificaciones

- Person-Centered TherapyDocumento3 páginasPerson-Centered TherapyMaleesha PereraAún no hay calificaciones

- PSYC 4110 PsycholinguisticsDocumento11 páginasPSYC 4110 Psycholinguisticsshakeelkhanturlandi5Aún no hay calificaciones

- Gambaran Pengelolaan Emergency Kit (Trolley) Di Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah (RSUD) Dr. Hasri Ainun HabibieDocumento10 páginasGambaran Pengelolaan Emergency Kit (Trolley) Di Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah (RSUD) Dr. Hasri Ainun HabibieRutharyantiSihotangAún no hay calificaciones

- Howardl j3 Depm 622 9040Documento7 páginasHowardl j3 Depm 622 9040api-279612996Aún no hay calificaciones

- LE 2 - Activity 1Documento3 páginasLE 2 - Activity 1Niña Gel Gomez AparecioAún no hay calificaciones

- Dhaval CVDocumento2 páginasDhaval CVPurva PrajapatiAún no hay calificaciones

- PRESTON HOLT - Cells Investigation LEXILE 610Documento6 páginasPRESTON HOLT - Cells Investigation LEXILE 610Brian HoltAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson1-Foundations of Management and OrganizationsDocumento21 páginasLesson1-Foundations of Management and OrganizationsDonnalyn VillamorAún no hay calificaciones

- Herzberg's Model: Motivating and Leading Self-InstructionalDocumento2 páginasHerzberg's Model: Motivating and Leading Self-Instructionalp.sankaranarayananAún no hay calificaciones

- Karakter Anak Usia Dini Yang Tinggal Di Daerah Pesisir PantaiDocumento12 páginasKarakter Anak Usia Dini Yang Tinggal Di Daerah Pesisir PantaiMoh. Ibnu UbaidillahAún no hay calificaciones

- Application of Soft Computing KCS056Documento1 páginaApplication of Soft Computing KCS056sahuritik314Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ade 149Documento74 páginasAde 149matt_langioneAún no hay calificaciones

- IManager U2000 Single-Server System Software Installation and Commissioning Guide (Windows 7) V1.0Documento116 páginasIManager U2000 Single-Server System Software Installation and Commissioning Guide (Windows 7) V1.0dersaebaAún no hay calificaciones

- National Creativity Olympiad 2013Documento11 páginasNational Creativity Olympiad 2013jonwal82Aún no hay calificaciones

- In The Modern World: Rizal, Zamboanga Del NorteDocumento10 páginasIn The Modern World: Rizal, Zamboanga Del NorteAlthea OndacAún no hay calificaciones

- Ai NotesDocumento76 páginasAi NotesEPAH SIRENGOAún no hay calificaciones

- FIRO Element BDocumento19 páginasFIRO Element Bnitin21822Aún no hay calificaciones

- Admission To Undergraduate Programmes (Full-Time)Documento14 páginasAdmission To Undergraduate Programmes (Full-Time)IndahmuthmainnahAún no hay calificaciones

- Curriculum Development in English Language EducationDocumento22 páginasCurriculum Development in English Language EducationHuyềnThanhLêAún no hay calificaciones

- Pro 17 PDFDocumento139 páginasPro 17 PDFdani2611Aún no hay calificaciones

- American Express: HR Policies and Practices of The CompanyDocumento13 páginasAmerican Express: HR Policies and Practices of The CompanySachin NakadeAún no hay calificaciones

- 2023 06 19 VacDocumento2 páginas2023 06 19 VacAnanyaAún no hay calificaciones