Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Case Digest Under Taxation

Cargado por

cdwernerDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case Digest Under Taxation

Cargado por

cdwernerCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case: Physical Therapy Org. vs. Municipal Board, G.R.

10448, August 30, 1957 SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. L-10448 August 30, 1957 IN THE MATTER OF A PETITION FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT REGARDING THE VALIDITY OF MUNICIPAL ORDINANCE NO. 3659 OF THE CITY OF MANILA. PHYSICAL THERAPY ORGANIZATION OF THE PHILIPPINES, INC., petitioner-appellant, vs. THE MUNICIPAL BOARD OF THE CITY OF MANILA and ARSENIO H. LACSON, as Mayor of the City of Manila, respondents-appellees. Mariano M. de Joya for appellant. City Fiscal Eugenio Angeles and Assistant Fiscal Arsenio Naawa for appellees. MONTEMAYOR, J.: The petitioner-appellant, an association of registered massagists and licensed operators of massage clinics in the City of Manila and other parts of the country, filed an action in the Court of First Instance of Manila for declaratory judgment regarding the validity of Municipal Ordinance No. 3659, promulgated by the Municipal Board and approved by the City Mayor. To stop the City from enforcing said ordinance, the petitioner secured an injunction upon filing of a bond in the sum of P1,000.00. A hearing was held, but the parties without introducing any evidence submitted the case for decision on the pleadings, although they submitted written memoranda. Thereafter, the trial court dismissed the petition and later dissolved the writ of injunction previously issued. The petitioner appealed said order of dismissal directly to this Court. In support of its appeal, petitioner-appellant contends among other things that the trial court erred in holding that the Ordinance in question has not restricted the practice of massotherapy in massage clinics to hygienic and aesthetic massage, that the Ordinance is valid as it does not regulate the practice of massage, that the Municipal Board of Manila has the power to enact the Ordinance in question by virtue of Section 18, Subsection (kk), Republic Act 409, and that permit fee of P100.00 is moderate and not unreasonable. Inasmuch as the appellant assails and discuss certain provisions regarding the ordinance in question, and it is necessary to pass upon the same, for purposes of ready reference, we are reproducing said ordinance in toto. ORDINANCE No. 3659 AN ORDINANCE REGULATING THE OPERATION OF MASSAGE CLINICS IN THE CITY OF MANILA AND PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATIONS THEREOF. Be it ordained by the Municipal Board of the City of Manila, that: Section 1. Definition. For the purpose of this Ordinance the following words and phrases shall be taken in the sense hereinbelow indicated: (a) Massage clinic shall include any place or establishment used in the practice of hygienic and aesthetic massage; (b) Hygienic and aesthetic massage shall include any system of manipulation of treatment of the superficial parts of the human body of hygienic and aesthetic purposes by rubbing, stroking, kneading, or tapping with the hand or an instrument; (c) Massagist shall include any person who shall have passed the required examination and shall have been issued a massagist certificate by the Committee of Examiners of Massagist,

or by the Director of Health or his authorized representative; (d) Attendant or helper shall include any person employed by a duly qualified massagist in any message clinic to assist the latter in the practice of hygienic and aesthethic massage; (e) Operator shall include the owner, manager, administrator, or any person who operates or is responsible for the operation of a message clinic. SEC. 2. Permit Fees. No person shall engage in the operation of a massage clinic or in the occupation of attendant or helper therein without first having obtained a permit therefor from the Mayor. For every permit granted under the provisions of this Ordinance, there shall be paid to the City Treasurer the following annual fees: (a) Operator of a massage (b) Attendant or helper P100.00 5.00

Said permit, which shall be renewed every year, may be revoked by the Mayor at any time for the violation of this Ordinance. SEC. 3. Building requirement. (a) In each massage clinic, there shall be separate rooms for the male and female customers. Rooms where massage operations are performed shall be provided with sliding curtains only instead of swinging doors. The clinic shall be properly ventilated, well lighted and maintained under sanitary conditions at all times while the establishment is open for business and shall be provided with the necessary toilet and washing facilities. (b) In every clinic there shall be no private rooms or separated compartment except those assigned for toilet, lavatories, dressing room, office or kitchen. (c) Every massage clinic shall "provided with only one entrance and it shall have no direct or indirect communication whatsoever with any dwelling place, house or building. SEC. 4. Regulations for the operation of massage clinics. (a) It shall be unlawful for any operator massagist, attendant or helper to use, or allow the use of, a massage clinic as a place of assignation or permit the commission therein of any incident or immoral act. Massage clinics shall be used only for hygienic and aesthetic massage. (b) Massage clinics shall open at eight o'clock a.m. and shall close at eleven o'clock p.m. (c) While engaged in the actual performance of their duties, massagists, attendants and helpers in a massage clinic shall be as properly and sufficiently clad as to avoid suspicion of intent to commit an indecent or immoral act; (d) Attendants or helpers may render service to any individual customer only for hygienic and aesthetic purposes under the order, direction, supervision, control and responsibility of a qualified massagist. SEC. 5. Qualifications No person who has previously been convicted by final judgment of competent court of any violation of the provisions of paragraphs 3 and 5 of Art. 202 and Arts. 335, 336, 340 and 342 of the Revised Penal Code, or Secs. 819 of the City of Manila, or who is suffering from any venereal or communicable disease shall engage in the occupation of massagist, attendant or helper in any massage clinic. Applicants for Mayor's permit shall attach to their application a police clearance and health certificate duly issued by the City Health Officers as well as a massagist certificate duly issued by the Committee or Examiners for Massagists or by the Director of Health or his authorized representatives, in case of massagists. SEC. 6. Duty of operator of massage clinic. No operator of massage clinic shall allow such clinic to operate without a duly qualified massagist nor allow, any man or woman to act as massagist, attendant or helper therein without the Mayor's permit provided for in the

preceding sections. He shall submit whenever required by the Mayor or his authorized representative the persons acting as massagists, attendants or helpers in his clinic. He shall place the massage clinic open to inspection at all times by the police, health officers, and other law enforcement agencies of the government, shall be held liable for anything which may happen with the premises of the massage clinic. SEC. 7. Penalty. Any person violating any of the provisions of this Ordinance shall upon conviction, be punished by a fine of not less than fifty pesos nor more than two hundred pesos or by imprisonment for not less than six days nor more than six months, or both such fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the court. SEC. 8. Repealing Clause. All ordinances or parts of ordinances, which are inconsistent herewith, are hereby repealed. SEC. 9. Effectivity. This Ordinance shall take effect upon its approval. Enacted, August 27, 1954. Approved, September 7, 1954. The main contention of the appellant in its appeal and the principal ground of its petition for declaratory judgment is that the City of Manila is without authority to regulate the operation of massagists and the operation of massage clinics within its jurisdiction; that whereas under the Old City Charter, particularly, Section 2444 (e) of the Revised Administrative Code, the Municipal Board was expressly granted the power to regulate and fix the license fee for the occupation of massagists, under the New Charter of Manila, Republic Act 409, said power has been withdrawn or omitted and that now the Director of Health, pursuant to authority conferred by Section 938 of the Revised Administrative Code and Executive Order No. 317, series of 1941, as amended by Executive Order No. 392, series, 1951, is the one who exercises supervision over the practice of massage and over massage clinics in the Philippines; that the Director of Health has issued Administrative Order No. 10, dated May 5, 1953, prescribing "rules and regulations governing the examination for admission to the practice of massage, and the operation of massage clinics, offices, or establishments in the Philippines", which order was approved by the Secretary of Health and duly published in the Official Gazette; that Section 1 (a) of Ordinance No. 3659 has restricted the practice of massage to only hygienic and aesthetic massage prohibits or does not allow qualified massagists to practice therapeutic massage in their massage clinics. Appellant also contends that the license fee of P100.00 for operator in Section 2 of the Ordinance is unreasonable, nay, unconscionable. If we can ascertain the intention of the Manila Municipal Board in promulgating the Ordinance in question, much of the objection of appellant to its legality may be solved. It would appear to us that the purpose of the Ordinance is not to regulate the practice of massage, much less to restrict the practice of licensed and qualified massagists of therapeutic massage in the Philippines. The end sought to be attained in the Ordinance is to prevent the commission of immorality and the practice of prostitution in an establishment masquerading as a massage clinic where the operators thereof offer to massage or manipulate superficial parts of the bodies of customers for hygienic and aesthetic purposes. This intention can readily be understood by the building requirements in Section 3 of the Ordinance, requiring that there be separate rooms for male and female customers; that instead of said rooms being separated by permanent partitions and swinging doors, there should only be sliding curtains between them; that there should be "no private rooms or separated compartments, except those assigned for toilet, lavatories, dressing room, office or kitchen"; that every massage clinic should be provided with only one entrance and shall have no direct or indirect communication whatsoever with any dwelling place, house or building; and that no operator, massagists, attendant or helper will be allowed "to use or allow the use of a massage clinic as a place of assignation or permit the commission therein of any immoral or incident act", and in fixing the operating hours of such clinic between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 p.m. This intention of the Ordinance

was correctly ascertained by Judge Hermogenes Concepcion, presiding in the trial court, in his order of dismissal where he said: "What the Ordinance tries to avoid is that the massage clinic run by an operator who may not be a masseur or massagista may be used as cover for the running or maintaining a house of prostitution." Ordinance No. 3659, particularly, Sections 1 to 4, should be considered as limited to massage clinics used in the practice of hygienic and aesthetic massage. We do not believe that Municipal Board of the City of Manila and the Mayor wanted or intended to regulate the practice of massage in general or restrict the same to hygienic and aesthetic only. As to the authority of the City Board to enact the Ordinance in question, the City Fiscal, in representation of the appellees, calls our attention to Section 18 of the New Charter of the City of Manila, Act No. 409, which gives legislative powers to the Municipal Board to enact all ordinances it may deem necessary and proper for the promotion of the morality, peace, good order, comfort, convenience and general welfare of the City and its inhabitants. This is generally referred to as the General Welfare Clause, a delegation in statutory form of the police power, under which municipal corporations, are authorized to enact ordinances to provide for the health and safety, and promote the morality, peace and general welfare of its inhabitants. We agree with the City Fiscal. As regards the permit fee of P100.00, it will be seen that said fee is made payable not by the masseur or massagist, but by the operator of a massage clinic who may not be a massagist himself. Compared to permit fees required in other operations, P100.00 may appear to be too large and rather unreasonable. However, much discretion is given to municipal corporations in determining the amount of said fee without considering it as a tax for revenue purposes: The amount of the fee or charge is properly considered in determining whether it is a tax or an exercise of the police power. The amount may be so large as to itself show that the purpose was to raise revenue and not to regulate, but in regard to this matter there is a marked distinction between license fees imposed upon useful and beneficial occupations which the sovereign wishes to regulate but not restrict, and those which are inimical and dangerous to public health, morals or safety. In the latter case the fee may be very large without necessarily being a tax. (Cooley on Taxation, Vol. IV, pp. 3516-17; underlining supplied.) Evidently, the Manila Municipal Board considered the practice of hygienic and aesthetic massage not as a useful and beneficial occupation which will promote and is conducive to public morals, and consequently, imposed the said permit fee for its regulation. In conclusion, we find and hold that the Ordinance in question as we interpret it and as intended by the appellees is valid. We deem it unnecessary to discuss and pass upon the other points raised in the appeal. The order appealed from is hereby affirmed. No costs. Paras, C.J., Bengzon, Padilla, Reyes, A., Bautista Angelo, Labrador, Concepcion, Reyes, J.B.L., Endencia and Felix, JJ., concur. Case: YMCA vs. CIR, 33 Phil. 217 (1916) COMMISSIONER G.R. No. Panganiban, J. OF INTERNAL REVENUE v. 124043 October 14, YMCA 1998

Doctrine: - Rental income derived by a tax-exempt organization from the lease of its properties, real or personal, is not exempt from income taxation, even if such income is exclusively used for the accomplishment of its objectives.

- A claim of statutory exemption from taxation should be manifest and unmistakable from the language of the law on which it is based. Thus, it must expressly be granted in a statute stated in a language too clear to be mistaken. Verba legis non est recedendum where the law does not distinguish, neither should we. - The bare allegation alone that one is a non-stock, non-profit educational institution is insufficient to justify its exemption from the payment of income tax. It must prove with substantial evidence that (1) it falls under the classification non-stock, non-profit educational institution; and (2) the income it seeks to be exempted from taxation is used actually, directly, and exclusively for educational purposes. - The Court cannot change the law or bend it to suit its sympathies and appreciations. Otherwise, it would be overspilling its role and invading the realm of legislation. The Court, given its limited constitutional authority, cannot rule on the wisdom or propriety of legislation. That prerogative belongs to the political departments of government. Facts: Private Respondent YMCA is a non-stock, non-profit institution, which conducts various programs and activities that are beneficial to the public, especially the young people, pursuant to its religious, educational and charitable objectives. YMCA earned income from leasing out a portion of its premises to small shop owners, like restaurants and canteen operators, and from parking fees collected from non-members. Petitioner issued an assessment to private respondent for deficiency taxes. Private respondent formally protested the assessment. In reply, the CIR denied the claims of YMCA. Issue: Whether or not the income derived from rentals of real property owned by YMCA subject to income tax Held: Yes. Income of whatever kind and character of non-stock non-profit organizations from any of their properties, real or personal, or from any of their activities conducted for profit, regardless of the disposition made of such income, shall be subject to the tax imposed under the NIRC. Rental income derived by a tax-exempt organization from the lease of its properties, real or personal, is not exempt from income taxation, even if such income is exclusively used for the accomplishment of its objectives. Because taxes are the lifeblood of the nation, the Court has always applied the doctrine of strict in interpretation in construing tax exemptions (Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Court of Appeals, 271 SCRA 605, 613, April 18, 1997). Furthermore, a claim of statutory exemption from taxation should be manifest and unmistakable from the language of the law on which it is based. Thus, the claimed exemption must expressly be granted in a statute stated in a language too clear to be mistaken (Davao Gulf Lumber Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue and Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 117359, p. 15 July 23, 1998). Verba legis non est recedendum. The law does not make a distinction. The rental income is taxable regardless of whence such income is derived and how it is used or disposed of. Where the law does not distinguish, neither should we. Private respondent also invokes Article XIV, Section 4, par. 3 of the Constitution, claiming that it is a non-stock, non-profit educational institution whose revenues and assets are used actually, directly and exclusively for educational purposes so it is exempt from taxes on its properties and income. This is without merit since the exemption provided lies on the payment of property tax, and not on the income tax on the rentals of its property. The bare allegation alone that one is a nonstock, non-profit educational institution is insufficient to justify its exemption from the payment of income tax.

For the YMCA to be granted the exemption it claims under the above provision, it must prove with substantial evidence that (1) it falls under the classification non-stock, non-profit educational institution; and (2) the income it seeks to be exempted from taxation is used actually, directly, and exclusively for educational purposes. Unfortunately for respondent, the Court noted that not a scintilla of evidence was submitted to prove that it met the said requisites. The Court appreciates the nobility of respondents cause. However, the Courts power and function are limited merely to applying the law fairly and objectively. It cannot change the law or bend it to suit its sympathies and appreciations. Otherwise, it would be overspilling its role and invading the realm of legislation. The Court regrets that, given its limited constitutional authority, it cannot rule on the wisdom or propriety of legislation. That prerogative belongs to the political departments of government. Case: Commissioner vs. Makasiar, 177 SCRA 27 (1989)

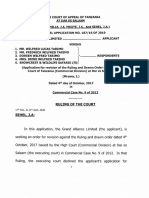

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. Nos. 111202-05 January 31, 2006 COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, Petitioner, vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS; Honorable Arsenio M. Gonong, Presiding Judge Regional Trial Court, Manila, Branch 8; Honorable MAURO T. ALLARDE, Presiding Judge, REGIONAL TRIAL COURT Kalookan City, Branch 123; AMADO SEVILLA and ANTONIO VELASCO, Special Sheriffs of Manila; JOVENAL SALAYON, Special Sheriff of Kalookan City, DIONISIO J. CAMANGON, Ex-Deputy Sheriff of Manila and CESAR S. URBINO, SR., doing business under the name and style "Duraproof Services," Respondents. DECISION AZCUNA, J.: These Petitions for Certiorari and Prohibition, with Prayers for a Writ of Preliminary Injunction and/or Temporary Restraining Order, are the culmination of several court cases wherein several resolutions and decisions are sought to be annulled. Petitioner Commissioner of Customs specifically assails the following: A) Decision of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Manila dated February 18, 1991 in Civil Case No. 89-51451; B) Order of the RTC of Kalookan dated May 28, 1991 in Special Civil Case No. C-234; C) Resolution of the Court of Appeals (CA) dated March 6, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 24669; D) Resolution of the CA dated August 6, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 28387; E) Resolution of the CA dated November 10, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 29317; F) Resolution of the CA dated May 31, 1993 in CA-G.R. No. CV-32746; and G) Decision of the CA dated July 19, 1993 in the consolidated petitions of CA-G.R. SP Nos. 24669, 28387 and 29317.

Petitioner also seeks to prohibit the CA and the RTC of Kalookan1 from further acting in CA-G.R. CV No. 32746 and Civil Case No. 234, respectively. The whole controversy revolves around a vessel and its cargo. On January 7, 1989, the vessel M/V "Star Ace," coming from Singapore laden with cargo, entered the Port of San Fernando, La Union (SFLU) for needed repairs. The vessel and the cargo had an appraised value, at that time, of more or less Two Hundred Million Pesos (P200,000,000). When the Bureau of Customs later became suspicious that the vessels real purpose in docking was to smuggle its cargo into the country, seizure proceedings were instituted under S.I. Nos. 02-89 and 03-89 and, subsequently, two Warrants of Seizure and Detention were issued for the vessel and its cargo.1awph!l.net Respondent Cesar S. Urbino, Sr., does not own the vessel or any of its cargo but claimed a preferred maritime lien under a Salvage Agreement dated June 8, 1989. To protect his claim, Urbino initially filed two motions in the seizure and detention cases: a Motion to Dismiss and a Motion to Lift Warrant of Seizure and Detention.2 Apparently not content with his administrative remedies, Urbino sought relief with the regular courts by filing a case for Prohibition, Mandamus and Damages before the RTC of SFLU3 on July 26, 1989, seeking to restrain the District Collector of Customs from interfering with his salvage operation. The case was docketed as Civil Case No. 89-4267. On January 31, 1991 the RTC of SFLU dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction because of the pending seizure and detention cases. Urbino then elevated the matter to the CA where it was docketed as CA-G.R. CV No. 32746. The Commissioner of Customs, in response, filed a Motion to Suspend Proceedings, advising the CA that it intends to question the jurisdiction of the CA before this Court. The motion was denied on May 31, 1993. Hence, in this petition the Commissioner of Customs assails the Resolution "F" recited above and seeks to prohibit the CA from continuing to hear the case. On January 9, 1990, while Civil Case No. 89-4267 was pending, Urbino filed another case for Certiorari and Mandamus with the RTC of Manila, presided by Judge Arsenio M. Gonong, 4 this time to enforce his maritime lien. Impleaded as defendants were the Commissioner of Customs, the District Collector of Customs, the owners of the vessel and cargo, Vlason Enterprises, Singkong Trading Company, Banco do Brazil, Dusit International Company Incorporated, Thai-Nam Enterprises Limited, Thai-United Trading Company Incorporated and Omega Sea Transport Company, and the vessel M/V "Star Ace." This case was docketed as Civil Case No. 89-51451. The Office of the Solicitor General filed a Motion to Dismiss on the ground that a similar case was pending with the RTC of SFLU. The Motion to Dismiss was granted on July 2, 1990, but only insofar as the Commissioner of Customs and the District Collector were concerned. The RTC of Manila proceeded to hear the case against the other parties and received evidence ex parte. The RTC of Manila later rendered a decision on February 18, 1991 finding in favor of Urbino (assailed Decision "A" recited above). Thereafter, on March 13, 1991, a writ of execution was issued by the RTC of Manila. Respondent Camangon was appointed as Special Sheriff to execute the decision and he issued a notice of levy and sale against the vessel and its cargo. The Commissioner of Customs, upon learning of the notice of levy and sale, filed with the RTC of Manila a motion to recall the writ, but before it could be acted upon, Camangon had auctioned off the vessel and the cargo to Urbino for One Hundred and Twenty Million Pesos (P120,000,000). The following day, Judge Gonong issued an order commanding Sheriff Camangon to cease and desist from implementing the writ. Despite the order, Camangon issued a Certificate of Sale in favor of Urbino. A week later, Judge Gonong issued another order recalling the writ of execution. Both cease and desist and recall orders of Judge Gonong were elevated by Urbino to the CA on April 12, 1991 where it was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 24669. On April 26, 1991, the CA issued a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) enjoining the RTC of Manila from enforcing its cease and desist and recall orders. The TRO was eventually substituted by a writ of preliminary injunction. A motion to lift the injunction was filed by the Commissioner of Customs but it was denied. Hence, in this petition the Commissioner of Customs

assails Resolution "C" recited above. On May 8, 1991, Urbino attempted to enforce the RTC of Manilas decision and the Certificate of Sale against the Bureau of Customs by filing a third case, a Petition for Certiorari, Prohibition and Mandamus with the RTC of Kaloocan.5 The case was docketed as Civil Case No. 234. On May 28, 1991, the RTC of Kaloocan ordered the issuance of a writ of preliminary injunction to enjoin the Philippine Ports Authority and the Bureau of Customs from interfering with the relocation of the vessel and its cargo by Urbino (assailed Order "B" recited above).1awph!l.net Meanwhile, on June 5, 1992, Camangon filed his Sheriffs Return with the Clerk of Court. On June 26, 1992, the Executive Judge for the RTC of Manila, Judge Bernardo P. Pardo,6 having been informed of the circumstances of the sale, issued an order nullifying the report and all proceedings taken in connection therewith. With this order Urbino filed his fourth case with the CA on July 15, 1992, a Petition for Certiorari, Prohibition and Mandamus against Judge Pardo. This became CAG.R. SP No. 28387. The CA issued a Resolution on August 6, 1992 granting the TRO against the Executive Judge to enjoin the implementation of his June 26, 1992 Order. Hence, in this petition the Commissioner of Customs assails Resolution "D" recited above. Going back to the seizure and detention proceedings, the decision of the District Collector of Customs was to forfeit the vessel and cargo in favor of the Government. This decision was affirmed by the Commissioner of Customs. Three appeals were then filed with the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) by different parties, excluding Urbino, who claimed an interest in the vessel and cargo. These three cases were docketed as CTA Case No. 4492, CTA Case No. 4494 and CTA Case No. 4500. Urbino filed his own case, CTA Case No. 4497, but it was dismissed for want of capacity to sue. He, however, was allowed to intervene in CTA Case No. 4500. On October 5, 1992, the CTA issued an order authorizing the Commissioner of Customs to assign customs police and guards around the vessel and to conduct an inventory of the cargo. In response, on November 3, 1992, Urbino filed a fifth Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition with the CA to assail the order as well as the jurisdiction of the Presiding Judge and Associate Judges of the CTA in the three cases. That case was docketed as CA G.R. SP No. 29317. On November 10, 1992, the CA issued a Resolution reminding the parties that the vessel is under the control of the appellate court in CA-G.R. SP No. 24669 (assailed Resolution "E" recited above). CA-G.R. SP Nos. 24669, 28387 and 29317 were later consolidated and the CA issued a joint Decision in July 19, 1993 nullifying and setting aside: 1) the Order recalling the writ of execution by Judge Gonong of the the RTC of Manila; 2) the Order of Executive Judge Pardo of the RTC of Manila nullifying the Sheriffs Report and all proceedings connected therewith; and 3) the October 19, 1993 Order of the CTA, on the ground of lack of jurisdiction. Hence, in these petitions, which have been consolidated, the Commissioner of Customs assails Decision "G" recited above.1awph! l.net For purposes of deciding these petitions, the assailed Decisions and Resolutions will be divided into three groups: 1. The Resolution of the CA dated May 31, 1993 in CA-G.R. No. CV-32746 with the additional prayer to enjoin the CA from deciding the said case. 2. The Order of the RTC of Kalookan dated May 28, 1991 in Special Civil Case No. C-234 with the additional prayer to enjoin the RTC of Kalookan from proceeding with said case. 3. The Decision of the RTC of Manila dated February 18, 1991 in Civil Case No. 89-51451, the Resolutions of the CA dated March 6, 1992, August 6, 1992, November 10, 1992 and the Decision of the CA dated July 19, 1993 in the consolidated petitions CA-G.R. SP Nos. 24669, 28387 and 29317. First Group The Commissioner of Customs seeks to nullify the Resolution of the CA dated May 31, 1993

denying the Motion to Suspend Proceedings and to prohibit the CA from further proceeding in CAG.R. No. CV-32746 for lack of jurisdiction. This issue can be easily disposed of as it appears that the petition has become moot and academic, with the CA having terminated CA-G.R. No. CV32746 by rendering its Decision on May 13, 2002 upholding the dismissal of the case by the RTC of SFLU for lack of jurisdiction, a finding that sustains the position of the Commissioner of Customs. This decision became final and entry of judgment was made on June 14, 2002.7 Second Group The Court now proceeds to consider the Order granting an injunction dated May 28, 1991 in Civil Case No. C-234 issued by the RTC of Kalookan. The Commissioner of Customs seeks its nullification and to prohibit the RTC of Kalookan from further proceeding with the case. The RTC of Kalookan issued the Order against the Philippine Ports Authority and Bureau of Customs solely on the basis of Urbinos alleged ownership over the vessel by virtue of his certificate of sale. By this the RTC of Kalookan committed a serious and reversible error in interfering with the jurisdiction of customs authorities and should have dismissed the petition outright. In Mison v. Natividad,8 this Court held that the exclusive jurisdiction of the Collector of Customs cannot be interfered with by regular courts even upon allegations of ownership. To summarize the facts in that case, a warrant of seizure and detention was issued against therein plaintiff over a number of vehicles found in his residence for violation of customs laws. Plaintiff then filed a complaint before the RTC of Pampanga alleging that he is the registered owner of certain vehicles which the Bureau of Customs are threatening to seize and praying that the latter be enjoined from doing so. The RTC of Pampanga issued a TRO and eventually, thereafter, substituted it with a writ of preliminary injunction. This Court found that the proceedings conducted by the trial court were null and void as it had no jurisdiction over the res subject of the warrant of seizure and detention, holding that: A warrant of seizure and detention having already been issued, presumably in the regular course of official duty, the Regional Trial Court of Pampanga was indisputably precluded from interfering in said proceedings. That in his complaint in Civil Case No. 8109 private respondent alleges ownership over several vehicles which are legally registered in his name, having paid all the taxes and corresponding licenses incident thereto, neither divests the Collector of Customs of such jurisdiction nor confers upon said trial court regular jurisdiction over the case. Ownership of goods or the legality of its acquisition can be raised as defenses in a seizure proceeding; if this were not so, the procedure carefully delineated by law for seizure and forfeiture cases may easily be thwarted and set to naught by scheming parties. Even the illegality of the warrant of seizure and detention cannot justify the trial courts interference with the Collectors jurisdiction. In the first place, there is a distinction between the existence of the Collectors power to issue it and the regularity of the proceeding taken under such power. In the second place, even if there be such an irregularity in the latter, the Regional Trial Court does not have the competence to review, modify or reverse whatever conclusions may result therefrom x x x. The facts in this case are like those in that case. Urbino claimed to be the owner of the vessel and he sought to restrain the PPA and the Bureau of Customs from interfering with his rights as owner. His remedy, therefore, was not with the RTC but with the CTA where the seizure and detention cases are now pending and where he was already allowed to intervene. Moreover, this Court, on numerous occasions, cautioned judges in their issuance of temporary restraining orders and writs of preliminary injunction against the Collector of Customs based on the principle enunciated in Mison v. Natividad and has issued Administrative Circular No. 7-99 to carry out this policy.9 This Court again reminds all concerned that the rule is clear: the Collector of Customs has exclusive jurisdiction over seizure and forfeiture proceedings and trial courts are precluded from assuming cognizance over such matters even through petitions for certiorari, prohibition or mandamus.

Third Group The Decision of the RTC of Manila dated February 18, 1991 has the following dispositive portion: WHEREFORE, IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, based on the allegations, prayer and evidence adduced, both testimonial and documentary, the Court is convinced, that, indeed, defendants/respondents are liable to plaintiff/petitioner in the amount prayed for in the petition for which [it] renders judgment as follows: 1. Respondent M/V Star Ace, represented by Capt. Nahum Rada, Relief Captain of the vessel and Omega Sea Transport Company, Inc., represented by Frank Cadacio is ordered to refrain from alienating or transfer[r]ing the vessel M/V Star Ace to any third parties; 2. Singko Trading Company to pay the following: a. Taxes due the Government; b. Salvage fees on the vessel in the amount of $1,000,000.00 based on the Lloyds Standard Form of Salvage Agreement; c. Preservation, securing and guarding fees on the vessel in the amount of $225,000.00; d. Salaries of the crew from August 16, 1989 to December, in the amount of $43,000.00 and unpaid salaries from January 1990 up to the present; e. Attorneys fees in the amount of P656,000.00; 3. Vlazon Enterprises to pay plaintiff in the amount of P3,000,000.00 for damages; 4. Banco do Brazil to pay plaintiff in the amount of $300,000.00 in damages; and finally, 5. Costs of suit. SO ORDERED. On the other hand, the CA Resolutions are similar orders for the issuance of a writ of preliminary injunction to enjoin Judge Gonong and Judge Pardo from enforcing their recall and nullification orders and the CTA from exercising jurisdiction over the case, to preserve the status quo pending resolution of the three petitions. Finally, the Decision of the CA dated July 19, 1993 disposed of all three petitions in favor of Urbino, and has the following dispositive portion: ACCORDINGLY, in view of the foregoing disquisitions, all the three (3) consolidated petitions for certiorari are hereby GRANTED. THE assailed Order of respondent Judge Arsenio Gonong of the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 8, dated, April 5, 1991, in the first assailed petition for certiorari (CA-G.R. SP No. 24669); the assailed Order of Judge Bernardo Pardo, Executive Judge of the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 8, dated July 6, 1992, in the second petition for certiorari (CA-G.R. SP No. 28387); and Finally, the assailed order or Resolution en banc of the respondent Court of Tax Appeals[,] Judges Ernesto Acosta, Ramon de Veyra and Manuel Gruba, under date of October 5, 1992, in the third petition for certiorari (CA-G.R. SP No. 29317) are all hereby NULLIFIED and SET ASIDE thereby giving way to the entire decision dated February 18, 1991 of the respondent Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 8, in Civil Case No. 89-51451 which remains valid, final and executory, if not yet wholly executed. THE writ of preliminary injunction heretofore issued by this Court on March 6, 1992 and reiterated on July 22, 1992 and this date against the named respondents specified in the dispositive portion of the judgment of the respondent Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 8, in the first petition for certiorari, which remains valid, existing and enforceable, is hereby MADE PERMANENT without

prejudice (1) to the petitioners remaining unpaid obligations to herein party-intervenor in accordance with the Compromise Agreement or in connection with the decision of the respondent lower court in CA-G.R. SP No. 24669 and (2) to the government, in relation to the forthcoming decision of the respondent Court of Tax Appeals on the amount of taxes, charges, assessments or obligations that are due, as totally secured and fully guaranteed payment by petitioners bond, subject to relevant rulings of the Department of Finance and other prevailing laws and jurisprudence. We make no pronouncement as to costs. SO ORDERED. The Court rules in favor of the Commissioner of Customs. First of all, the Court finds the decision of the RTC of Manila, in so far as it relates to the vessel M/V "Star Ace," to be void as jurisdiction was never acquired over the vessel.10 In filing the case, Urbino had impleaded the vessel as a defendant to enforce his alleged maritime lien. This meant that he brought an action in rem under the Code of Commerce under which the vessel may be attached and sold.11 However, the basic operative fact for the institution and perfection of proceedings in rem is the actual or constructive possession of the res by the tribunal empowered by law to conduct the proceedings.12 This means that to acquire jurisdiction over the vessel, as a defendant, the trial court must have obtained either actual or constructive possession over it. Neither was accomplished by the RTC of Manila. In his comment to the petition, Urbino plainly stated that "petitioner has actual[sic] physical custody not only of the goods and/or cargo but the subject vessel, M/V Star Ace, as well."13 This is clearly an admission that the RTC of Manila did not have jurisdiction over the res. While Urbino contends that the Commissioner of Customs custody was illegal, such fact, even if true, does not deprive the Commissioner of Customs of jurisdiction thereon. This is a question that ought to be resolved in the seizure and forfeiture cases, which are now pending with the CTA, and not by the regular courts as a collateral matter to enforce his lien. By simply filing a case in rem against the vessel, despite its being in the custody of customs officials, Urbino has circumvented the rule that regular trial courts are devoid of any competence to pass upon the validity or regularity of seizure and forfeiture proceedings conducted in the Bureau of Customs, on his mere assertion that the administrative proceedings were a nullity.14 On the other hand, the Bureau of Customs had acquired jurisdiction over the res ahead and to the exclusion of the RTC of Manila. The forfeiture proceedings conducted by the Bureau of Customs are in the nature of proceedings in rem15 and jurisdiction was obtained from the moment the vessel entered the SFLU port. Moreover, there is no question that forfeiture proceedings were instituted and the vessel was seized even before the filing of the RTC of Manila case. The Court is aware that Urbino seeks to enforce a maritime lien and, because of its nature, it is equivalent to an attachment from the time of its existence. 16 Nevertheless, despite his liens constructive attachment, Urbino still cannot claim an advantage as his lien only came about after the warrant of seizure and detention was issued and implemented. The Salvage Agreement, upon which Urbino based his lien, was entered into on June 8, 1989. The warrants of seizure and detention, on the other hand, were issued on January 19 and 20, 1989. And to remove further doubts that the forfeiture case takes precedence over the RTC of Manila case, it should be noted that forfeiture retroacts to the date of the commission of the offense, in this case the day the vessel entered the country.17 A maritime lien, in contrast, relates back to the period when it first attached, 18 in this case the earliest retroactive date can only be the date of the Salvage Agreement. Thus, when the vessel and its cargo are ordered forfeited, the effect will retroact to the moment the vessel entered Philippine waters.

Accordingly, the RTC of Manila decision never attained finality as to the defendant vessel, inasmuch as no jurisdiction was acquired over it, and the decision cannot be binding and the writ of execution issued in connection therewith is null and void. Moreover, even assuming that execution can be made against the vessel and its cargo, as goods and chattels to satisfy the liabilities of the other defendants who have an interest therein, the RTC of Manila may not execute its decision against them while, as found by this Court, these are under the proper and lawful custody of the Bureau of Customs.19 This is especially true when, in case of finality of the order of forfeiture, the execution cannot anymore cover the vessel and cargo as ownership of the Government will retroact to the date of entry of the vessel into Philippine waters. As regards the jurisdiction of the CTA, the CA was clearly in error when it issued an injunction against it from deciding the forfeiture case on the basis that it interfered with the subject of ownership over the vessel which was, according to the CA, beyond the jurisdiction of the CTA. Firstly, the execution of the Decision against the vessel and cargo, as aforesaid, was a nullity and therefore the sale of the vessel was invalid. Without a valid certificate of sale, there can be no claim of ownership which Urbino can present against the Government. Secondly, as previously stated, allegations of ownership neither divest the Collector of Customs of such jurisdiction nor confer upon the trial court jurisdiction over the case. Ownership of goods or the legality of its acquisition can be raised as defenses in a seizure proceeding.20 The actions of the Collectors of Customs are appealable to the Commissioner of Customs, whose decision, in turn, is subject to the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the CTA.21 Clearly, issues of ownership over goods in the custody of custom officials are within the power of the CTA to determine.1awphi1.net WHEREFORE, the consolidated petitions are GRANTED. The Decision of the Regional Trial Court of Manila dated February 18, 1991 in Civil Case No. 89-51451, insofar as it affects the vessel M/V "Star Ace," the Order of the Regional Trial Court of Kalookan dated May 28, 1991 in Special Civil Case No. C-234, the Resolution of the Court of Appeals dated March 6, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 24669, the Resolution of the Court of Appeals dated August 6, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 28387, the Resolution of the Court of Appeals dated November 10, 1992 in CA-G.R. SP No. 29317 and the Decision of the Court of Appeals dated July 19, 1993 in the consolidated petitions in CA-G.R. SP Nos. 24669, 28387 and 29317 are all SET ASIDE. The Regional Trial Court of Kalookan is enjoined from further acting in Special Civil Case No. C-234. The Order of respondent Judge Arsenio M. Gonong dated April 5, 1991 and the Order of then Judge Bernardo P. Pardo dated June 26, 1992 are REINSTATED. The Court of Tax Appeals is ordered to proceed with CTA Case No. 4492, CTA Case No. 4494 and CTA Case No. 4500. No pronouncement as to costs.

También podría gustarte

- Act on Anti-Corruption and the Establishment and Operation of the Anti-Corruption: Civil Rights Commission of the Republic of KoreaDe EverandAct on Anti-Corruption and the Establishment and Operation of the Anti-Corruption: Civil Rights Commission of the Republic of KoreaAún no hay calificaciones

- Consumer Protection in India: A brief Guide on the Subject along with the Specimen form of a ComplaintDe EverandConsumer Protection in India: A brief Guide on the Subject along with the Specimen form of a ComplaintAún no hay calificaciones

- 012-Physical Therapy Organization v. Municipal Board of Manila, Et. Al., August 30, 1957Documento5 páginas012-Physical Therapy Organization v. Municipal Board of Manila, Et. Al., August 30, 1957Jopan SJAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy Organization v. Municipal Board of Manila, G.R. No. L-10448, August 30, 1957Documento5 páginasPhysical Therapy Organization v. Municipal Board of Manila, G.R. No. L-10448, August 30, 1957AkiNiHandiongAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy Org. vs. Municipal BoardDocumento5 páginasPhysical Therapy Org. vs. Municipal BoardMermerRectoAún no hay calificaciones

- In Re Physical Therapy Org. of The Phils., Inc. v. Municipal Board of Manila PDFDocumento5 páginasIn Re Physical Therapy Org. of The Phils., Inc. v. Municipal Board of Manila PDFKristabelleCapaAún no hay calificaciones

- 37 Physical Therapy vs. Municipal Board 101 Phil 1142Documento5 páginas37 Physical Therapy vs. Municipal Board 101 Phil 1142Queenie Hadiyah Diampuan SaripAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy Org V Municipal BoardDocumento2 páginasPhysical Therapy Org V Municipal BoardM A J esty FalconAún no hay calificaciones

- CASE DIGEST: Physical Therapy Organization vs. Municipal Board of Manila G.R. No. L-10448Documento2 páginasCASE DIGEST: Physical Therapy Organization vs. Municipal Board of Manila G.R. No. L-10448Lyka Angelique CisnerosAún no hay calificaciones

- Iloilo City Regulation Ordinance 2015-306Documento4 páginasIloilo City Regulation Ordinance 2015-306Iloilo City CouncilAún no hay calificaciones

- Doctrine: in Matalin Coconut v. Municipal Council of Malabang, Lanao Del Sur, 143 SCRA 404, An OrdinanceDocumento7 páginasDoctrine: in Matalin Coconut v. Municipal Council of Malabang, Lanao Del Sur, 143 SCRA 404, An OrdinanceCharmaine Key AureaAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Theraphy Org. V Municipal BoardDocumento1 páginaPhysical Theraphy Org. V Municipal BoardLeyardAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy Organization v. Municipal BoardDocumento1 páginaPhysical Therapy Organization v. Municipal BoardpaoloAún no hay calificaciones

- Exam Cases 2Documento100 páginasExam Cases 2Rustan FrozenAún no hay calificaciones

- Republic Vs Philippine Rabbit Bus Lines Inc Philippine Air Lines, Inc Vs Romeo F Eduetal Caltex Philippines, Inc Vs Coa EtalDocumento12 páginasRepublic Vs Philippine Rabbit Bus Lines Inc Philippine Air Lines, Inc Vs Romeo F Eduetal Caltex Philippines, Inc Vs Coa EtaldoraemoanAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy Organization Vs Municipal Board DigestDocumento1 páginaPhysical Therapy Organization Vs Municipal Board DigestMaureen CoAún no hay calificaciones

- Federico N. Alday For Petitioners. Dakila F. Castro For RespondentsDocumento8 páginasFederico N. Alday For Petitioners. Dakila F. Castro For RespondentsKimberly SendinAún no hay calificaciones

- Federico N. Alday For Petitioners. Dakila F. Castro For RespondentsDocumento12 páginasFederico N. Alday For Petitioners. Dakila F. Castro For Respondentsjack fackageAún no hay calificaciones

- II. General Powers and Attributes of LGUDocumento251 páginasII. General Powers and Attributes of LGUMylene GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pubcorp Batch 2Documento130 páginasPubcorp Batch 2Kates Jastin AguilarAún no hay calificaciones

- B014 de La Cruz vs. Paras GRs L-42571-72Documento5 páginasB014 de La Cruz vs. Paras GRs L-42571-72Mai AlterAún no hay calificaciones

- 7-12 Full CasesDocumento76 páginas7-12 Full CasesShane Irish Pagulayan LagguiAún no hay calificaciones

- Ii General Powers Attributes of LgusDocumento191 páginasIi General Powers Attributes of LgusAllyna GonzalesAún no hay calificaciones

- VICENTE DE LA CRUZ, ET AL. vs. EDGARDO L. PARAS, ET AL.Documento12 páginasVICENTE DE LA CRUZ, ET AL. vs. EDGARDO L. PARAS, ET AL.sahara lockwoodAún no hay calificaciones

- Administrative Order 2010-0034Documento15 páginasAdministrative Order 2010-0034Esperanza Evaristo-ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- Cruz vs. Paras, 123 SCRA 569 (1983)Documento7 páginasCruz vs. Paras, 123 SCRA 569 (1983)rizavillalobos10Aún no hay calificaciones

- State RegulationsDocumento12 páginasState RegulationsSamuel CrawfordAún no hay calificaciones

- Ra 4226Documento3 páginasRa 4226Kenneth RafolsAún no hay calificaciones

- Legal MedicineDocumento117 páginasLegal MedicineJane JaramilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Code of Ethics: Registered Beauty TherapistsDocumento9 páginasCode of Ethics: Registered Beauty Therapistssilvia oanaAún no hay calificaciones

- PubCorp October 15 Cases PDFDocumento64 páginasPubCorp October 15 Cases PDFMiguel AguirreAún no hay calificaciones

- Ra 4226Documento5 páginasRa 4226Ralph Gene Trabasas FloraAún no hay calificaciones

- RA 9173 Articla 7-9Documento7 páginasRA 9173 Articla 7-9Patricia OrtegaAún no hay calificaciones

- Practice of Dentistry:-: PrefaceDocumento7 páginasPractice of Dentistry:-: PrefaceSanAún no hay calificaciones

- PubCorp October 15 CasesDocumento50 páginasPubCorp October 15 CasesMiguel AguirreAún no hay calificaciones

- Medtech LawsDocumento19 páginasMedtech LawsJon Nicole DublinAún no hay calificaciones

- City of Manila VS Judge LaguioDocumento20 páginasCity of Manila VS Judge LaguioQueenie Joy AccadAún no hay calificaciones

- Written Report IN Contemporary NursingDocumento3 páginasWritten Report IN Contemporary NursingLilian FloresAún no hay calificaciones

- Enforce ControlDocumento14 páginasEnforce ControlLilian FloresAún no hay calificaciones

- UntitledDocumento12 páginasUntitledJabeth IbarraAún no hay calificaciones

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocumento3 páginasBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledArreis IlioacAún no hay calificaciones

- Dela Cruz v. ParasDocumento5 páginasDela Cruz v. ParasAntonJohnVincentFriasAún no hay calificaciones

- State Regulation of Hospital Operation PDFDocumento14 páginasState Regulation of Hospital Operation PDFFaith Alexis GalanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Missouri Laws LicensingDocumento3 páginasMissouri Laws LicensingskaluAún no hay calificaciones

- Republic Act NoDocumento14 páginasRepublic Act Nojohn_esturcoAún no hay calificaciones

- Activity No. 2Documento2 páginasActivity No. 2Kookie MarinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Dela Cruz Vs ParasDocumento3 páginasDela Cruz Vs ParasNowell SimAún no hay calificaciones

- An Act Requiring The Licensure of All Hospitals in The Philippines and Authorizing The Bureau of Medical Services To Serve As The Licensing AgencyDocumento4 páginasAn Act Requiring The Licensure of All Hospitals in The Philippines and Authorizing The Bureau of Medical Services To Serve As The Licensing AgencyFides ServandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Professional Code of EthicsDocumento18 páginasProfessional Code of Ethicsct303 uuuAún no hay calificaciones

- OTbillDocumento17 páginasOTbillDino Roel De GuzmanAún no hay calificaciones

- 22-96 The Law of Practicing Medicine and DentistryDocumento6 páginas22-96 The Law of Practicing Medicine and DentistryZakariyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Renewal of Licenses, Permits. - Being TheDocumento10 páginasRenewal of Licenses, Permits. - Being TheLeslie OctavianoAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Laboratory Laws NotesDocumento12 páginasClinical Laboratory Laws NotesRezza Mae Jamili100% (2)

- Ra 8344Documento6 páginasRa 8344April Isidro100% (1)

- 1987 Decree No 2 On Non-DoctorsDocumento11 páginas1987 Decree No 2 On Non-DoctorsSaad MirzaAún no hay calificaciones

- RA - 4226 - Hospital - Licensure - Act - PDF Filename - UTF-8''RA 4226 Hospital Licensure ActDocumento4 páginasRA - 4226 - Hospital - Licensure - Act - PDF Filename - UTF-8''RA 4226 Hospital Licensure ActJEnLipataAún no hay calificaciones

- Commercial Medical Marihuana FacilitiesDocumento14 páginasCommercial Medical Marihuana FacilitiesWWMTAún no hay calificaciones

- Republic Acts: Approved: October 23, 1972Documento1 páginaRepublic Acts: Approved: October 23, 1972LoveAnneAún no hay calificaciones

- DC Board of CosmetolofyDocumento64 páginasDC Board of CosmetolofyDani StewartAún no hay calificaciones

- Protection of Human Rights and Criminal Justice SystemDocumento28 páginasProtection of Human Rights and Criminal Justice SystemShubham Brijwani100% (1)

- Facts:: 9. Tomali V Civil Service CommissionDocumento3 páginasFacts:: 9. Tomali V Civil Service CommissionEmmanuelMedinaJr.Aún no hay calificaciones

- (Digest) Modequillo v. BrevaDocumento2 páginas(Digest) Modequillo v. BrevaKarla BeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Rashidul Jafar Order AttachmentDocumento109 páginasRashidul Jafar Order AttachmentharshAún no hay calificaciones

- Attachement of Decree. GRAND ALLIANCE LTD VS MR. WILFRED LUCAS TARIMO & OTHERS 2019 NEWDocumento28 páginasAttachement of Decree. GRAND ALLIANCE LTD VS MR. WILFRED LUCAS TARIMO & OTHERS 2019 NEWSaid Maneno100% (1)

- United States v. Blythe, 4th Cir. (2006)Documento3 páginasUnited States v. Blythe, 4th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- 12th FebruaryDocumento19 páginas12th Februaryajay kiranAún no hay calificaciones

- Motion Set Aside Default GA Magistrate CourtDocumento9 páginasMotion Set Aside Default GA Magistrate CourtJanet and James80% (5)

- Name: - Class: LLB 2 - Roll No: - Subject: - Subject: Prof.A.Kottapalle - Topic: Legal Services AuthorityDocumento12 páginasName: - Class: LLB 2 - Roll No: - Subject: - Subject: Prof.A.Kottapalle - Topic: Legal Services AuthorityVrushaliAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Ryan Eaddy, 4th Cir. (2013)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Ryan Eaddy, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- P V BadosoDocumento3 páginasP V BadosoEduard Doron FloresAún no hay calificaciones

- Malto V PeopleDocumento5 páginasMalto V PeopleCinja ShidoujiAún no hay calificaciones

- N 400 QuestionnaireDocumento6 páginasN 400 QuestionnaireionutdanciuAún no hay calificaciones

- Alfelor Vs HalasanDocumento1 páginaAlfelor Vs HalasanAirisa MolaerAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Nollora V People GR NoDocumento2 páginas1 Nollora V People GR NoCamille Tapec100% (1)

- Final Moot R44Documento23 páginasFinal Moot R44Anurag Kushwaha100% (1)

- Notice of LossDocumento18 páginasNotice of LossAbigail JimenezAún no hay calificaciones

- Joseph M. Kalady v. Joe W. Booker, Warden and United States Parole Commission, 104 F.3d 367, 10th Cir. (1996)Documento5 páginasJoseph M. Kalady v. Joe W. Booker, Warden and United States Parole Commission, 104 F.3d 367, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Teaching Profession ReportDocumento20 páginasTeaching Profession ReportSharmiene Hazel Monteroso Oñes-BasanAún no hay calificaciones

- Republic Savings Bank Vs CirDocumento1 páginaRepublic Savings Bank Vs CirRobertAún no hay calificaciones

- Consumer Protection Act - Part 2Documento15 páginasConsumer Protection Act - Part 2RiyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Carlos Slay DocumentsDocumento90 páginasCarlos Slay DocumentsPhil AmmannAún no hay calificaciones

- IMMIG AILA National - ManualDocumento340 páginasIMMIG AILA National - Manualmatt29nyc100% (1)

- CAASI Vs Court of AppealsDocumento2 páginasCAASI Vs Court of AppealsJessie Albert Catapang0% (1)

- Tayag Vs Benguet Consolidated CDDocumento2 páginasTayag Vs Benguet Consolidated CDAnonymous jbul0WI6Aún no hay calificaciones

- Judge Dolly GeeDocumento7 páginasJudge Dolly GeemveincenAún no hay calificaciones

- Felonies and Circumstances Which Affect Criminal Liability Chapter One FeloniesDocumento93 páginasFelonies and Circumstances Which Affect Criminal Liability Chapter One FeloniesPots SimAún no hay calificaciones

- Subject: Customs ACT, 1969 Compliance ChecklistDocumento3 páginasSubject: Customs ACT, 1969 Compliance ChecklistNiloy AhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- Forest Hills and Country Club, Inc. v. Kings Properties Corp., G.R. No. 212833Documento2 páginasForest Hills and Country Club, Inc. v. Kings Properties Corp., G.R. No. 212833Joyce50% (2)

- Power of President To Grant PardonDocumento10 páginasPower of President To Grant PardonSubh AshishAún no hay calificaciones