Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

August J. Fabens v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 519 F.2d 1310, 1st Cir. (1975)

Cargado por

Scribd Government DocsDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

August J. Fabens v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 519 F.2d 1310, 1st Cir. (1975)

Cargado por

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

519 F.

2d 1310

75-2 USTC P 9572

August J. FABENS, Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, RespondentAppellee.

No. 75-1057.

United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit.

Argued May 5, 1975.

Decided June 30, 1975.

James Sawyer, Great Neck, N.Y., with whom charles R. Van De Walle,

Great Neck, N.Y., was on brief, for appellant.

Arthur L. Bailey, Atty., Tax Div., Dept., of Justice, with whom Scott P.

Crampton,Asst. Atty. Gen., Gilbert E. Andrews, and Jonathan S. Cohen,

Attys., Tax Div., Dept. of Justice, Washington, D.C., on brief, for

appellee.

Before COFFIN, Chief Judge, McENTEE and CAMPBELL, Circuit

Judges.

McENTEE, Circuit Judge.

The parties stipulated that from 1953 to 1969 taxpayer Fabens maintained in a

trust account municipal bonds, the income from which was tax-exempt, and

other securities the income from which was taxable. The trust also realized

capital gains and losses from transactions involving its holdings. Upon

termination the fair market value of the trust assets included a considerable

amount of unrealized capital appreciation1 which was reflected in the fiduciary

fees paid on termination and computed under local law as a percentage of

current market value. Taxpayer deducted the full amount of these commissions

as expenses for the production of income under Int.Rev.Code Sec. 212.2 The

Commissioner disallowed a portion of this deduction pursuant to Int.Rev.Code

Sec. 265(1) prohibiting the deduction of expenses directly or indirectly

allocable to the production of tax-exempt income. The fees were disallowed in

the ratio of tax-exempt income over the life of the trust to total income

(including net capital gains) realized during that period.3

2($740,093

-------($211,443

28.57 percent),

and this percentage was applied to the total amount of receiving and paying

commissions incurred upon termination of the trust ($50,695) to determine the

amount of the termination commissions ($14,484) allocable to tax-exempt

income. The Commissioner made a separate allocation with respect to the

annual commissions (income and principal commissions) for 1969 in the total

amount of $3,241. The Commissioner allocated this commission by computing

the total income (taxable and tax exempt) of the trust for 1969 ($24,743), and

computing tax-exempt income for 1969 ($9,028), as a percentage of total

income

4($ 9,028

------- = 36.49 percent).

($24,743

The percentage was applied to the annual commissions ($3,241) for 1969 to

determine the amount ($1,183) allocable to tax-exempt income for that year.

The total amount ($15,667) allocable to tax-exempt income ($14,484 of the

termination charges, plus $1,183 of the annual commissions) was disallowed as

a deduction pursuant to the provisions of Section 265 of the Code. The

Commissioner allowed the remaining amounts ($38,269) as deductions for

1969.

In the Tax court taxpayer argued that this formula was not reasonable in the

light of all the facts and circumstances, Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.265-1(c), because it

did not reflect the unrealized appreciation of the trust assets. The court upheld

the Commissioner's allocation and taxpayer appeals.

The Commissioner argues there was no evidence that the trust assets were

actually managed for capital appreciation; and that to the extent they were so

managed, the Commissioner's inclusion in his allocation formula of net capital

gains realized over the life of the trust would reasonably reflect this fact. We

disagree on both counts. As an initial matter even if achieving appreciation

were not a prime goal of the trustee's management, it would remain unclear

how fees created solely because of a rise in the value of taxable investments

could be considered "allocable" within the statute to the production of tax

exempt income. At any rate, while there is no specific evidence as to the

trustee's investment objectives, that appreciation was such an objective is

inferable from the facts that the trustee apparently insisted on compensation for

appreciation when the trust was established, and that appreciation under the

trustee's management comprised more than half of corpus value at termination.

As to the second point, since the trustee's decision to sell securities (thereby

realizing capital appreciation) is dictate by considerations other than that of the

trust's termination date, there is no necessary reason to suppose that the net

capital gains realized over the life of the trust and included in the

Commissioner's formula will fairly reflect the trustee's division of labor

between exempt and taxable income-production activities in administering the

trust.4 Since the value of the property comprising corpus generates the fee, an

allocation measure like taxpayer's which somehow reflects that value will

seemingly result in a fairer apportionment.5 See M. Ferguson, J. Freeland & R.

Stephens, Federal Income Taxation of Estates and Beneficiaries 492-93, 644 n.

115 (1970). The Tax Court characterized the appreciation as "ephemeral." but

the commissions it produced represented an outlay very tangible indeed.

8

It is clear as a general matter that expenditures aimed at the production of

future capital gains are deductible under Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.212-1(b). It is also

clear as a general matter that in the application of Sec. 265, an allocation based

on realized income is not mandatory, Rev.Rul. 63-27, and this was true as

regards trustees' fees too, at least under the 1939 Code. Edward Mallinckrodt,

Jr., 2 T.C. 1128, 1148 (1943). The Commissioner argues, however, that where a

trust is involved, the concept of distributable net income, see Int.Rev.Code Sec.

643(a), and the special system of taxation in subchapter J (dealing with trusts

and estates) are important components of a "all the facts and circumstances"

mentioned in Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.265-1(c). Manufacturers Hanover Trust Co. v.

United States, 312 F.2d 785, 795, 160 Ct.Cl. 582 (1963). Trusts are taxable

entities which compute their deductions basically as do individuals, though in

order to effectuate the "flow-through" scheme of taxation of subchapter J they

are allowed a special deduction for distributions to beneficiaries. Int.Rev.Code

Sec. 641(b); Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.641(b)-1. This distribution deduction is limited

by distributable net income, Int.Rev.Code Sec. 661(a). The statute contemplates

that items of deduction like fiduciary fees be allocated exclusively among items

of distributable net income. Int.Rev.Code Sec. 661(b); Treas.Reg. Sec.

1.652(b)-3(b). Thus, in Manufacturers Hanover Trust v. United States, supra,

and Tucker v. Commissioner, 322 F.2d 86 (2d Cir.1963), the courts upheld the

Commissioner's excluding from the allocation base realized capital gains

allocable to corpus not required to be distributed in the current year, hence

excluded from distributable net income. Int.Rev.Code Sec. 643(a)(3). Since

capital appreciation is never included in distributable net income, the

Commissioner contends, it may never be included in the base for allocating

commissions between exempt and taxable income.

9

The Commissioner himself acknowledges that the allocation of termination

fees like those involved here may not be subject to the strictures of the

distributable net income concept, conceding that the deductions may instead

pass to beneficiaries under the general allocation provisions and the excess

deduction provisions of Sec. 642(h)(2). We think this is in fact the case.

Distributable net income is an annual concept. Int.Rev.Code Sec. 643(a).

Manufacturers Hanover Trust and Tucker involved annual commissions and

income beneficiaries.6 Since income beneficiaries would not be taxed for

capital gains (which were allocated to corpus under the trust instrument), the

Court of Claims saw no reason to give them the added advantage of a deduction

for expenses which would be inflated if it included fees based on such gains-gains which would eventually be a tax burden to another (the remainderman).

312 F.2d at 796. In the present case taxpayer will receive the benefit of the

appreciation if anyone does. There is no authority in the code for computing, as

the Commissioner in effect wishes, a second, analogous distributable net

income based on figures from the entire duration of the trust. Thus the court in

Whittemore v. United States, 383 F.2d 824 (8th Cir.1967), facing the identical

issue as we are, seemingly did not feel constrained by Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.652(b)3 in applying Sec. 642(h)(2).7

10

In sum, we agree that the Commissioner's allocation was proper as to the

annual fees but conclude it was not reasonable in light of all the facts and

circumstances, including taxpayer's proposed allocation, insofar as the

termination fees were concerned.

11

Affirmed in part and reversed in part. Remanded for further proceedings

consistent with this opinion.

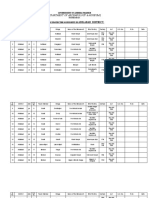

The stipulation as to these amounts is summarized in the following table:

Applicable to

municipal

bond holdings

Income Due to dividends and

interest realized over the

life of the trust, 4/9/536/16/69 .............................. $211,443

Capital gain income realized

over the life of the trust as

Applicable to

non-municipal

bond holdings

503,641

Tota

715

a result of sales, liquidations,

distributions or uncollectibility

of principal, 4/9/53-6/16/69 ........ ($127,340)

Unrealized appreciation during

period 4/9/53-6/16/69 .................. --0-Ordinary income realized by

the trust for the calendar

year 1969 ............................ $ 9,028

152,349

$1,476

15,715

Upon termination of the trust on June 16, 1969, taxpayer paid trustee the

following fiduciary commissions:

A.

Receiving and Paying Commissions:

(a) Receiving Commissions:

(i) Receiving commissions based on

capital appreciation of assets sold,

redeemed and collected ................... $ 717.31

(ii) Receiving commissions based on

capital increase of assets distributed ... 18,401.12

----------

C.

25

$1,476,023

B.

24

$19,118.4

(b) Paying Commissions:

(i) Paying commission based on market value at date of

distribution, administrative expenses and assets

remaining on hand .................................... 31,576.3

--------TOTAL Receiving and Paying Commissions:

$50,694.7

Trustee's annual principal commission (based on the then

current market value of the fund)

1,279.4

Trustee's annual income commission (based on income

collected for period 5/3/68-6/1/69)

1,920.5

--------TOTAL fiduciary commissions due and paid Bankers Trust

Company upon termination of Trust Agreement in June

1969

$53,894.6

In allocating a portion of these expenses to the tax-exempt income, the

Commissioner first determined the total amount of tax-exempt income earned

by the trust between 1953 and 1969 ($211,443), and then computed the total

income of the trust for this period ($740,093), which included taxable interest

and dividends and capital gains, plus the tax-exempt income. Tax-exempt

income was then expressed as a percentage of total income

Here the unrealized appreciation exceeded the net capital gain included in the

Commissioner's ratio by a factor of 60. It is not wholly unrealistic to conceive a

trust owning common stock, which experiences enormous appreciation during

the trust's existence while paying little or nothing in dividends as growth stocks

often do, along with a single municipal bond paying a steady coupon interest.

In such a situation the commissioner's formula would obviously result in a

distorted apportionment of termination fees paid for the whole job of

administering the trust. See In re Gildersleeve's Estate, 75 Misc.2d 207, 347

N.Y.S.2d 96 (Sur.Ct.1973)

5

This may be a special "fact and circumstance" to be considered in making the

allocation under Treas.Reg. Sec. 1.265-1(c). M. Ferguson, J. Freeland & R.

Stephens, Federal Income Taxation of Estates and Beneficiaries 493 (1970)

The court in Manufacturers Hanover Trust twice noted, 312 F.2d at 794, 796 &

nn. 13, 15, that the case would "present different problems" if the allowable

deductions exceeded distributable net income as the Tax Court found was the

case here

Though the allocation fashioned by the court in that case was the one adopted

by the Commissioner here, the possibility of considering capital appreciation

was not before the court there. The problem it perceived in allocating on the

basis of corpus value--that part of the value of the exempt securities represented

appreciation which would be taxable when realized even though the income

from these securities was not--is absent here where the exempt securities

actually depreciated

También podría gustarte

- Marcia Brady Tucker and Estate of Carll Tucker, Deceased, Marcia Brady Tucker, Carll Tucker, JR., and Luther Tucker, Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 322 F.2d 86, 2d Cir. (1963)Documento5 páginasMarcia Brady Tucker and Estate of Carll Tucker, Deceased, Marcia Brady Tucker, Carll Tucker, JR., and Luther Tucker, Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 322 F.2d 86, 2d Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Manufacturers Hanover Trust Co., Robert P. Payne and Charles C. Parlin, As Trustees U/i 6/4/32 by Anne D. Dillon, As Grantor v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 431 F.2d 664, 2d Cir. (1970)Documento6 páginasManufacturers Hanover Trust Co., Robert P. Payne and Charles C. Parlin, As Trustees U/i 6/4/32 by Anne D. Dillon, As Grantor v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 431 F.2d 664, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Sheldon B. Bufferd Phyllis Bufferd v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 952 F.2d 675, 2d Cir. (1992)Documento6 páginasSheldon B. Bufferd Phyllis Bufferd v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 952 F.2d 675, 2d Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Abkco Industries, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 482 F.2d 150, 3rd Cir. (1973)Documento10 páginasAbkco Industries, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 482 F.2d 150, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Lewyt Corp. v. Commissioner, 349 U.S. 237 (1955)Documento13 páginasLewyt Corp. v. Commissioner, 349 U.S. 237 (1955)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- CRC Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. CRC Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 693 F.2d 281, 3rd Cir. (1982)Documento4 páginasCRC Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. CRC Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 693 F.2d 281, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Old Mission Portland Cement Co. v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 289 (1934)Documento4 páginasOld Mission Portland Cement Co. v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 289 (1934)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocumento6 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Skelly Oil Co., 394 U.S. 678 (1969)Documento16 páginasUnited States v. Skelly Oil Co., 394 U.S. 678 (1969)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Mills Estate, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Mills Estate, Inc, 206 F.2d 244, 2d Cir. (1953)Documento4 páginasMills Estate, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Mills Estate, Inc, 206 F.2d 244, 2d Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Bayshore Gardens, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 267 F.2d 55, 2d Cir. (1959)Documento6 páginasBayshore Gardens, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 267 F.2d 55, 2d Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Adolph Coors Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 519 F.2d 1280, 10th Cir. (1975)Documento6 páginasAdolph Coors Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 519 F.2d 1280, 10th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Julia R. & Estelle L. Foundation Incorporated v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 598 F.2d 755, 2d Cir. (1979)Documento5 páginasJulia R. & Estelle L. Foundation Incorporated v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 598 F.2d 755, 2d Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- National Life Insurance Company and Subsidiaries v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 103 F.3d 5, 2d Cir. (1996)Documento7 páginasNational Life Insurance Company and Subsidiaries v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 103 F.3d 5, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Babcock & Wilcox Co. v. Pedrick. Babcock & Wilcox Tube Co. v. Pedrick, 212 F.2d 645, 2d Cir. (1954)Documento12 páginasBabcock & Wilcox Co. v. Pedrick. Babcock & Wilcox Tube Co. v. Pedrick, 212 F.2d 645, 2d Cir. (1954)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Bruce A. and Marianne S. Prabel v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 882 F.2d 820, 3rd Cir. (1989)Documento12 páginasBruce A. and Marianne S. Prabel v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 882 F.2d 820, 3rd Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Daniel S. Kampel and Clarisse Kampel v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 634 F.2d 708, 2d Cir. (1980)Documento13 páginasDaniel S. Kampel and Clarisse Kampel v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 634 F.2d 708, 2d Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Colony, Inc. v. Commissioner, 357 U.S. 28 (1958)Documento8 páginasColony, Inc. v. Commissioner, 357 U.S. 28 (1958)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Helvering v. Bliss, 293 U.S. 144 (1934)Documento6 páginasHelvering v. Bliss, 293 U.S. 144 (1934)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Bangor & Aroostook R. Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 193 F.2d 827, 1st Cir. (1951)Documento9 páginasBangor & Aroostook R. Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 193 F.2d 827, 1st Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- I. J. Marshall and Claribel Marshall v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Flora H. Miller v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 510 F.2d 259, 10th Cir. (1975)Documento8 páginasI. J. Marshall and Claribel Marshall v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Flora H. Miller v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 510 F.2d 259, 10th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Don E. Williams Co. v. Commissioner, 429 U.S. 569 (1977)Documento16 páginasDon E. Williams Co. v. Commissioner, 429 U.S. 569 (1977)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 901, Docket 88-4155Documento9 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 901, Docket 88-4155Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Gold Kist, Inc. v. Comr. of IRS, 110 F.3d 769, 11th Cir. (1997)Documento9 páginasGold Kist, Inc. v. Comr. of IRS, 110 F.3d 769, 11th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Helvering v. American Dental Co., 318 U.S. 322 (1943)Documento8 páginasHelvering v. American Dental Co., 318 U.S. 322 (1943)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Tate & Lyle, Inc. and Subsidiaries v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service, 87 F.3d 99, 3rd Cir. (1996)Documento14 páginasTate & Lyle, Inc. and Subsidiaries v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service, 87 F.3d 99, 3rd Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Harry M. Stevens, Inc. v. James W. Johnson, Former Collector of Internal Revenue For The Third District of New York, 238 F.2d 436, 2d Cir. (1956)Documento5 páginasHarry M. Stevens, Inc. v. James W. Johnson, Former Collector of Internal Revenue For The Third District of New York, 238 F.2d 436, 2d Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Public Service Company of Oklahoma, 241 F.2d 18, 10th Cir. (1957)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Public Service Company of Oklahoma, 241 F.2d 18, 10th Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Estate of John Schlosser, Deceased. Raymond Schlosser v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 277 F.2d 268, 3rd Cir. (1960)Documento4 páginasEstate of John Schlosser, Deceased. Raymond Schlosser v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 277 F.2d 268, 3rd Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Thomas Browne Foster v. United States, 329 F.2d 717, 2d Cir. (1964)Documento5 páginasThomas Browne Foster v. United States, 329 F.2d 717, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- G. Douglas Burck and Marjorie W. Burck v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 533 F.2d 768, 2d Cir. (1976)Documento10 páginasG. Douglas Burck and Marjorie W. Burck v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 533 F.2d 768, 2d Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. South Texas Lumber CoDocumento9 páginasCommissioner of Internal Revenue v. South Texas Lumber CoScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Freuler v. Helvering, 291 U.S. 35 (1934)Documento12 páginasFreuler v. Helvering, 291 U.S. 35 (1934)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Olympic Radio & Television., 349 U.S. 232 (1955)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Olympic Radio & Television., 349 U.S. 232 (1955)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Thomas M. Ferrill, Jr. and Louise B. Ferrill v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 684 F.2d 261, 3rd Cir. (1982)Documento7 páginasThomas M. Ferrill, Jr. and Louise B. Ferrill v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 684 F.2d 261, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Willcuts v. Milton Dairy Co., 275 U.S. 215 (1927)Documento4 páginasWillcuts v. Milton Dairy Co., 275 U.S. 215 (1927)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- CIR v. CADocumento2 páginasCIR v. CALynne SanchezAún no hay calificaciones

- Mass. Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. United States, 288 U.S. 269 (1933)Documento5 páginasMass. Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. United States, 288 U.S. 269 (1933)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Mutual Shoe Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 238 F.2d 729, 1st Cir. (1956)Documento7 páginasMutual Shoe Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 238 F.2d 729, 1st Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Schulde v. Commissioner, 372 U.S. 128 (1963)Documento12 páginasSchulde v. Commissioner, 372 U.S. 128 (1963)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Raymond J. Dusek and Velma W. Dusek v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 376 F.2d 410, 10th Cir. (1967)Documento5 páginasRaymond J. Dusek and Velma W. Dusek v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 376 F.2d 410, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Noel D. Induni and Janet E. Induni v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 990 F.2d 53, 2d Cir. (1993)Documento8 páginasNoel D. Induni and Janet E. Induni v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 990 F.2d 53, 2d Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Nat Dorfman and Annette Dorfman v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 394 F.2d 651, 2d Cir. (1968)Documento8 páginasNat Dorfman and Annette Dorfman v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 394 F.2d 651, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Merchants Industrial Bank, A Corporation Organized and Existing Under The Laws of The State of Colorado v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 475 F.2d 1063, 10th Cir. (1973)Documento5 páginasMerchants Industrial Bank, A Corporation Organized and Existing Under The Laws of The State of Colorado v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 475 F.2d 1063, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Pepsi-Cola Niagara Bottling Corporation, 399 F.2d 390, 2d Cir. (1968)Documento9 páginasCommissioner of Internal Revenue v. Pepsi-Cola Niagara Bottling Corporation, 399 F.2d 390, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Commissioner v. Wheeler, 324 U.S. 542 (1945)Documento5 páginasCommissioner v. Wheeler, 324 U.S. 542 (1945)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Security Mills Co. v. Comm'r., 321 U.S. 281 (1944)Documento6 páginasSecurity Mills Co. v. Comm'r., 321 U.S. 281 (1944)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Bufferd v. Commissioner, 506 U.S. 523 (1993)Documento10 páginasBufferd v. Commissioner, 506 U.S. 523 (1993)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Atlas Life Insurance Company v. United States, 333 F.2d 389, 10th Cir. (1964)Documento16 páginasAtlas Life Insurance Company v. United States, 333 F.2d 389, 10th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Active Media Services, Inc. Response To Internal Revenue Service Form 5701 Tax Year Ended 6/30/2008Documento3 páginasActive Media Services, Inc. Response To Internal Revenue Service Form 5701 Tax Year Ended 6/30/2008tommydAún no hay calificaciones

- Susan L. Ketchum v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 697 F.2d 466, 2d Cir. (1982)Documento12 páginasSusan L. Ketchum v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 697 F.2d 466, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United Cal. Bank v. United States, 439 U.S. 180 (1978)Documento29 páginasUnited Cal. Bank v. United States, 439 U.S. 180 (1978)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: Nos. 148-150, Dockets 29926-29928Documento9 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: Nos. 148-150, Dockets 29926-29928Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Pacific First Federal Savings Bank v. Commissioner Internal Revenue Service, 961 F.2d 800, 1st Cir. (1992)Documento11 páginasPacific First Federal Savings Bank v. Commissioner Internal Revenue Service, 961 F.2d 800, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Abkco Industries, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 486 F.2d 1371, 3rd Cir. (1973)Documento6 páginasAbkco Industries, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 486 F.2d 1371, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 451. Docket 28752Documento5 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 451. Docket 28752Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Dexsil Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 147 F.3d 96, 2d Cir. (1998)Documento9 páginasDexsil Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 147 F.3d 96, 2d Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Mills, Incorporated v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 250 F.2d 55, 1st Cir. (1957)Documento6 páginasMills, Incorporated v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 250 F.2d 55, 1st Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- David Gambardella v. G. Fox & Co., 716 F.2d 104, 2d Cir. (1983)Documento26 páginasDavid Gambardella v. G. Fox & Co., 716 F.2d 104, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento20 páginasUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento21 páginasCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento8 páginasPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento6 páginasBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento24 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento22 páginasConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento50 páginasUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento100 páginasHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento10 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento14 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento27 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento17 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento18 páginasWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento10 páginasNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Verification Handbook For Investigative ReportingDocumento79 páginasVerification Handbook For Investigative ReportingRBeaudryCCLE100% (2)

- In - Gov.uidai ADHARDocumento1 páginaIn - Gov.uidai ADHARvamsiAún no hay calificaciones

- Taste of IndiaDocumento8 páginasTaste of IndiaDiki RasaptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Service Industries LimitedDocumento48 páginasService Industries Limitedmuhammadtaimoorkhan86% (7)

- Amazon InvoiceDocumento1 páginaAmazon InvoiceChandra BhushanAún no hay calificaciones

- Research For ShopeeDocumento3 páginasResearch For ShopeeDrakeAún no hay calificaciones

- Ebook Service Desk vs. Help Desk. What Is The Difference 1Documento18 páginasEbook Service Desk vs. Help Desk. What Is The Difference 1victor molinaAún no hay calificaciones

- List of Solar Energy Operating Applications 2020-03-31Documento1 páginaList of Solar Energy Operating Applications 2020-03-31Romen RealAún no hay calificaciones

- Debate Motions SparringDocumento45 páginasDebate Motions SparringJayden Christian BudimanAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 CBT Sample Questionnaires-1Documento101 páginas1 CBT Sample Questionnaires-1Mhee FaustinaAún no hay calificaciones

- La Salle Charter School: Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Assets - Modified Cash BasisDocumento5 páginasLa Salle Charter School: Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Assets - Modified Cash BasisF. O.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Shiva Gayathri Mantra - Dhevee PDFDocumento4 páginasShiva Gayathri Mantra - Dhevee PDFraghacivilAún no hay calificaciones

- Phrasal Verbs and IdiomaticDocumento9 páginasPhrasal Verbs and IdiomaticAbidah Sarajul Haq100% (1)

- Crisologo-Jose Vs CA DigestDocumento1 páginaCrisologo-Jose Vs CA DigestMarry LasherasAún no hay calificaciones

- Kentucky Economic Development Guide 2010Documento130 páginasKentucky Economic Development Guide 2010Journal CommunicationsAún no hay calificaciones

- The Powers To Lead Joseph S. Nye Jr.Documento18 páginasThe Powers To Lead Joseph S. Nye Jr.George ForcoșAún no hay calificaciones

- Admissions and ConfessionsDocumento46 páginasAdmissions and ConfessionsAlexis Anne P. ArejolaAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Management Education: Piet NaudéDocumento147 páginasContemporary Management Education: Piet Naudérolorot958Aún no hay calificaciones

- Maintain Aircraft Records & Remove Liens Before SaleDocumento1 páginaMaintain Aircraft Records & Remove Liens Before SaleDebs MaxAún no hay calificaciones

- RGPV Enrollment FormDocumento2 páginasRGPV Enrollment Formg mokalpurAún no hay calificaciones

- Criminal Investigation 11th Edition Swanson Test BankDocumento11 páginasCriminal Investigation 11th Edition Swanson Test BankChristopherWaltonnbqyf100% (14)

- Chap 1 ScriptDocumento9 páginasChap 1 ScriptDeliza PosadasAún no hay calificaciones

- Protected Monument ListDocumento65 páginasProtected Monument ListJose PerezAún no hay calificaciones

- Petition For The Issuance of A New Owner's Duplicate TCTDocumento4 páginasPetition For The Issuance of A New Owner's Duplicate TCTNikel TanAún no hay calificaciones

- General Math Second Quarter Exam ReviewDocumento5 páginasGeneral Math Second Quarter Exam ReviewAgnes Ramo100% (1)

- Cooperative by LawsDocumento24 páginasCooperative by LawsMambuay G. MaruhomAún no hay calificaciones

- 978191228177Documento18 páginas978191228177Juan Mario JaramilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Power Plant Cooling IBDocumento11 páginasPower Plant Cooling IBSujeet GhorpadeAún no hay calificaciones

- BP Code of ConductDocumento112 páginasBP Code of ConductLuis ZequeraAún no hay calificaciones

- Matrix of Activities For The Submission of Tasks For ResearchDocumento5 páginasMatrix of Activities For The Submission of Tasks For ResearchJAY LORRAINE PALACATAún no hay calificaciones