Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Ymj 29 233

Cargado por

MarthaMorales0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

8 vistas6 páginaspolimorfismo

Título original

ymj-29-233

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentopolimorfismo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

8 vistas6 páginasYmj 29 233

Cargado por

MarthaMoralespolimorfismo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 6

Yonsei Medical Journal

Vol. 28, No. 3, 1968

Olivopontocerebellar Atrophy

Il Saing Choi', Myung Sik Lee", Won Tsen Kim’ and Kyung Kyu Choi?

Between 1985 and 1987, 31 patients with sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy (SOPCA) and 3 patients

with familial olivopontocerebellar atrophy (FOPCA) were examined in the Neurologic Clinic of Yongdong Severance *

Hospital. The incidence of the disease among our neurology clinic patients was 0.9%, and 3.4% of those patients

were admitted. Seventeen of them were men and seventeen women, and their ages of onset ranged from 16

to 75 years (mean, 48.2 years). In comparison with SOPCA, the disease began earlier in FOPCA (mean age,

51.0 VS 19.3 years), but there were no other differences in clinical feature of the disease. Four patients had

parkinsonism, one dementia, and one ophthalmoplegia. None presented spinal involvement or abnormal

movements. Fight had a coexisting disease; 3, chronic alcoholism; 2, hypertension: 2, diabetes mellitus; and 1,

‘malignant neoplasm.

Key Words: Olivopontocerebellar atrophy, FOPCA, SOPCA

Olivopontocerebellar atrophy (PCA) is a term

coined by Dejerine and Thomas which comprises as

series of heterogenous diseases whose only common

fator is the loss of neurons in the ventral portion of

the pons, inferior olives and cerebellar cortex, Present-

ly the OPCAs are included under the general heading,

of multiple system atrophy.

OPCA may be clinically diagnosed by means of

history, including pertient family history, characteristic

signs, and in the past, a pneumoencephalogram (PEG).

With the advent of computed tomography (CT), these

patients may be evaluated without the need for PEG

(Aita 1978).

Since Menzel's description of this disorder in 1981,

numerous clinical studies have been performed in

‘America and Europe (Konigsmark and Weiner 1970;

Landis et al. 1974; Berciano 1982; Harding 1982).

However, few reports about this order as it is found

in Korea have appeared in print (Lim et al. 1984; Jeon

Received March 30, 1988

‘Accepted May 24, 1988

Department of Neurology’, Yongdong Severance Hospital, Yonsi

University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Ewha

‘Woman's University, Seoul, Korea

‘Address reprint requests to Dr. 1S Choi, Department of

Neurology, Yongdong Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College

‘of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Number 3

et al. 1984; Lee et al. 1985).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 1985 and 1987, a total of 3,596 patients

{994 admissions) were seen at the Neurologic Clinic,

Yongdong Severance Hospital, Yonsei University

Medical Center.

Of them, the diagnosis of OPCA was made in 34

cases, Parkinson's disease in 150 cases, and Alzhei-

mers disease in 5 cases.

Thirty-four patients with OPCA were classified accor-

ding to incidence, sex, age, family history, duration

of illness, clinical signs and symptoms, and coexisting

diseases, The disease was divided into an hereditary

type and a sporadic group, based on the Greenfield's

mothed (Greenfield, 1954).

CT brain scans were performed in all patients, EEG

(clectroencephalogram) in 15 patients, and BAEP

(brainstem auditory evoked potentials) in.6 patients.

No pathologic study was done.

The diagnostic criteria of OPCA were the follow-

ing: 1) neurologic disturbances including cerebellar,

pyramidal, extrapyramidal andlor spinal involvement;

2) family history; and 3) abnormal C-T brain scan fin-

dings such as atrophy of the pons and cerebellum,

with enlargement of the 4th ventricle and ambient,

prepontine, and quadrigerminal cisterns.

233

Ui Saing Choi et al

‘Table 1. Clinical summary of 34 patients With olivopontocerebellar atrophy

‘Age of Duration Symptoms and signs coexisting

No Sex ——________Smmmroms and signs ___

onset of illness cerebellar and pyramidal extrapyramidal other eaotee

7M 16 12 _ ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, — ‘ophthalmoplegia autosomal

hyperreflexia dominant

2 M 2 6 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperreflexia, _ 7

pathologic reflex

30 F 2 4 ataxia, dysarthria _ — a

4 F a 3 ataxia, hyperreflexia bradykinesia, masked inappropriate _

face, rigidity, laughing

shortstep gait, tremor

5M 54 1 ataxia, hyperreflexia bradykinesia, . inappropriate OM

masked face, rigidity. laughing

6M 48 4 ataxia, hyperreflexia, intention tremor bradykinesia, masked —~ —

7 face, rigidity, short-step *

gait

7 M 40 10. dysarthria, dysphagia, hyperreflexia masked face, rigidity, inappropriate alcoholism

short-step gait, tremor laaghing

BF 59 3 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperreflexia dementia, urinary uterine Ca

incontience

9M 2% 6 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperreflexia, == — hearing toss (ou) —~

nystagmus

10M 54 5 ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, _ _ hypertension

spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention

tremor

11 F 46 * 1 ataxia, dysarthria _ _ -

2M 38 hyperreflexia, spasticity hypertension

BM 54 1 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperreflexia, _ alcoholism

nystagmus, pathologic reflex

“WF 83 2 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperreflexia, == —~ _ _

pathologic reflex

BF 49 3.‘ ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia -

1% F 6 7 ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, _ _

spasticity, hyperreflexia

vr 88 8 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, = =

: hyperieflexia c

1% M "68 1 ataxia, hyperreflexia _ _ ~

199 F 58 3 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, _ _ om

hyperreflexia

20 F 54 10 ataxia, dysarthria — _ —

21M 49 1 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, - _ alcoholism

hyperreflexia, pathologic reflex

22M. 75 2 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, _ _ _

hyperreflexia, pathologic reflex

BF Bf 2 ataxia, dysarthria, hyperteflexia, — — _

pathologic reflex

24 M55 10_ ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, — = =

spasticity, hyperreflexia

2 F 52 11 ataxia, spasticity, hyperreflexia _ ~

2% F 43 1 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, _ _

hyperreflexia

234 Volume 29

Olivopontocerebellar Atrophy

‘Age of Duration

No Sex i

onset of illness cerebellar and pyramidal

Symptoms and signs

coexisting.

extrapyramidal disorder

7 FS 2 ataxia, hyperreflexia -

28 M64 2 ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia _ =

29M 50 4 ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity,

hyperrefiexia

30 F 56 2 ataxia, hyperreflexia, pathologic reflex —

BF 37 6 ataxia, dysarthria =

32 M27 2 ataxia, spasticity, pathologic reflex = —

33M 45 3. ataxia, spasticity, pathologic reflex ‘opticatrophy with = =~,

depigmentation we

3445, 7 ataxia, spasticity, nystagmus, _ _ ~

pathologic reflex

RESULTS

The incidence of OPCA was 0.% of the total group

in our neurologic clinic, and 3.4% of those admitted

(cf Parkinson's disease, 4.1 and 15.1%; Alzheimer’s

disease, 0.14 and 0.5%).

‘A dlinical summary of the 34 patients with OPCA

is given in Table 1

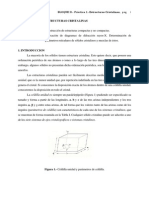

Of the 34 patients, 3 were classified as hereaitary,

with an autosomal dominant transmission (Fig, 1), and

31 were sporadic.

There were 17 men and 17 women. The ages of

‘onset in OPCA ranged from 16 to 75 years (mean,

48.2 years), with the peak incidence in the 5th and

6th decades. The age of onset in famial OPCA (FOP-

A) ranged from 16 to 22 years (mean, 19.3 years),

and that of sporadic OPCA (SOPCA), 26 to 75 years

(mean, 51.0 years) (Table 2).

The duration of the disease varied between 1 year

and 12 years (average duration, 3.9 years).

The initial symptom of OPCA usually was

cerebellar ataxia, especially involving the gait, but 4

patients exhibited parkinsonian symptoms initially. All

patients except two (94.5%) had ataxia, 25(73.5%)

hypereflexia, and 23 (67.6%) dysarthria, Other clinical

features included spasticity, dysphagia, tremor, rigidity

and pathologic reflexes. In rare cases, urinary incon-

tinence, optic atrophy, dementia, and

ophthalmoplegia were noted, None had spinal in-

volvement or abnormal movements (Table 3). There

was no difference in clinical manifestations except for

age of onset between FOPCA and SOPCA.

Fight (23.5%) had a coexisting disease: 3, chronic

alcoholism; 2, hypertension; 2, diabetes mellitus; and

‘one, carcinoma of uterine cervix. EEGs in 15 patients

‘Number 3

G5) () (20)

3 8s

Yon YF

Q stax terse

Zlenws Di vovns

afd

Fig. 1. Pedigrees of three patients with familial OPCA.

235,

U Saing. Choi et al

Table 2. Age of onset and sex distribution in 34 patients with

‘OPCA

= >

Age Male Female . Total

(years)

below 20 1 o 1

2029 3 1 4

3039 ° 1 1

40-49 4 5 9

5059 6 8 15

6069 2 1 3

over 70 1 ° 1

Total 7 v1 3h

Table 3. The fequencies of clinical features in 34 patients

with OPCA

‘Clinical finding No % Clinical finding No %

Ataxia 32 94.1 Bradykinesia 3 88

Hyperreflexia 25 73.5 Short-step gait 3 88

Dysarthria 23 67.6 Inappropriate laugh 3. 88

Spasticity 15 44.1 Nystagmus 3 88

Pathologic reflex 1132.4 Dementia 129

Dysphagia 6 176 Urinary incontinence 1 2.9

Tremor 4118 Ophthalmoplegia. 1 2.9

Rigidity 4 118 Optic atrophy 129

Masked face 4 11.8 Hearing loss 1.29

and BAEPs in 6 patients were obtained, and all were

normal.

DISCUSSION

The olivopontopocerebellar atrophies (OPCA) are

a group’ of diseases characterized by the loss of

neurons in the cerebellar cortex, basis pontis and in-

ferior olivary nuclei, There may be neuronal loss to

a variable degree in the spinal cord, cerebral cortex

and basal ganglia (Landis et al. 1974). Although OPCA

was first reported by Menzel in 1981, OPCA is a term

coined by Dejerine and Thomas who separated their

isolated case from the familial type described by

Menzel (Konigsmark & Weiner 1970). Thereafter

several mothods of classification of OPCA have been

suggested.

Greenfield (1954) led the OPCA’s into an

hereditary type and a sporadic type. Pratt (1967) in

a review of hereditary diseases of the nervous system,

divided the OPCA’s into 2 groups; those with spinal

236

ord involvement and those with the absence of spinal

cord involvement. Becker divided the OPCA’s into 3

types: 1) a dorginant type as described by Menzel;

2) a recessive ‘Hoe including sporadic and 3) typical

types with varing clinical presentations (Harding, 1984),

Konigsmark and Weiner (1970) divided the OPCA’s

into 5 categories; type 1, dominant; type 11, recessive;

type 111, with retinal degeneration; type 1V, Schut

and Haymaker; type V, with dementia, ophthal-

moplegia and extrapyramidal signs.

The literature contains descriptions of varjoys

clinical studies of OPCA, but many of them ware

review article concerned with cases and families (ghut

1950; Landis et al. 1974; Berciano 1982; Harding 1982).

OPCA is a rare disorder of multisystem degeneration.

The incidence of OPCA herein is lower than that of

Parkinson's disease, but higher than that of Alzheimer’s

disease. This finding differs between Korea and other

countries. The age of onset in SOPCA is unually mid-

dle age or older, while FOPCA begins earlier than

SOPCA. The reported sex ratios vary (Schut 1950; Lan-

dis et al. 1974; Berciano 1982), but gender does not

appéar to effect the incidence of OPCA. The dura-

tion of the disease varies between months and several

years, and FOPCA usually lasts longer than SOPCA

(Berciano 1982). As other authors have already in-

dicated (Konigsmark and Weiner 1970; Landis et al.

1974; Berciano 1982), the clinical picture usually

begins with cerebellar ataxia as we found herein,

When parkinsonian symptoms are found among the

first manifestations, they will always be important

symptoms throughout the course of the disease.

In contrast with the greater frequency of ataxic gait

in the early stages, as the disease progresses, the

cerebellar syndrome always becomes static and

kinetic. Dysarthria is also a constant symptom as we

found herein. The type of dysarthria varies among

bulbar or pseudobulbar, slow and monotonous, or

as a mixture of these. Parkinsonian symptoms were

reported in 25 of the 45 cases reviewed by

Rosenhagen (1943), and in 40% of the patients of Jell-

inger and Tamowska-Dziduszko (1971). Of the series

herein, only 4 patients (12.9%) had parkinsonism, Ab-

normal movement considered as a whole are

significantly more frequent in FOPCA (Bercino 1982).

None had abnormal movements in this series.

Dementia was reported in 16 of the 25 cases review-

ed by Jellinger and Tamowska-Dziduszko (1971), and

in 11.1 to 22.2% of the patients of Berciano (1982),

but we had only one case of dementia. Spinal symp-

toms usually were associated with FOPCA, but those

were significantly less frequent is SOPCA (Berciono

1982; Harding 1982). In the series herein, none had

Volume 29

Clivopontocerebellar Atrophy

spinal involvement. In addition, OPCA'had various

clinical features such as urinary incontinence, op- ”

hthalmoplegia, optic atrophy, and so on.

In the past, the pneumoencephlogram (PEG) had

been the only diagnostic test available to confirm the

diagnosis of OPCA during life (Aita 1978; Gilroy and

lynn 1978). With the advent of computed tomo-

graphy (CT), OPCA may be evaluated without the

need for PEG, The CT brain scan findings of OPCA

were atrophy of the pons and cerebellum, with

enlargement of the 4th ventricle and ambient, prepon-

tine and quadrigerminal cisterns (Aita 1978). Gilroy

and Lynn (1978) reported that their 3 patients with

OPCA showed abnormal BAEP findings, and the in-

nocuous AEP procedure might be used in conjunc-

tion with the CT scan in the diagnosis of OPCA,

eliminating the need for PEG.

OPCA is differentiated from various neurologic

diseases. OPCA is distinguished from Friedreich atax-

ia by the relatively late onset and the absence of sings

and symptoms of the spinal cord disease (Thilenius

and Grossman 1961). In familial cases, hereditary

cerebellar ataxia is more difficult in view of persisting

uncertainties regarding the classification of hereditary

ataxia (Hoffman et al. 1971; Hanes et al. 1984). The

family history is of primary importance. Posterior fossa

tumor and cerebellar degeneration occurring as a

remote effect of carcinoma should be considered in

the differential diagnosis (Rowland 1984). Some cases

with rigidity and tremor may initially be mistaken for

Parkinson’s disease. CT usually shows enlargement of

the prepontine cistern and 4th ventricle (Rowland

1984), Recently, Plaitakis and co-workers (1980)

described a significant reduction in the activity of the

enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase in several patients

with receissively inherited OPCA. If this finding is con-

firmed, it would provide a means to indentify a

subgroup of patients and offer a marker for genetic

counseling (Sorbi et al. 1986).

The literature defines OPCAs as a group of genetic

disorders, but most of the cases herein are sporadic.

The causes of SOPCA are unknown. Etiological

possibilities include toxic factors, a specific deficien-

Cy oF possibly a receissive hereditary disease of late

onset.

In the series herein, 3 patients had a history of

alcoholism, But alchol induced CNS lesions usually dit

fer from those of OPCA (Victor et al. 1959). So we

believe alcohol consumption does not contribute to

the development of OPCA. It also appears that

previous ilinesses play no part either. Konigsmark and

Weiner (1970) suggest that many sporadic cases pro-

bably reflect an unrecognized recessive heredity.

Number 3

In conclusion, OPCAs are not rare in Korea, and

it is a characteristic clinical feature of OPCA in Korea

that SOPCAs are exclusively more common than

FOPCAs.

REFERENCES

Aita JF: Cranial computerized tomography and Marie's atax-

la, Arch Neurol 35:55-56, 1978

Berciano J: Olivopontocerebellar atrophy: A review of 1375

cases. J Neurol Sci 53:253:272, 1982 dl

Greenfield JG: The spinocerebellar degeneration. Charles

Thomas, tlinois, 1954, 45

Gilroy J, Lynn GE: Computerized tomography and auditory

evoked potentials: Use in the diagnosis of olivopon-

tocerebellar degeneration. Arch Neurol 35:143-147, 1978

Haines JL, Schut U, Weitkamp LR, et al: Spinocerebellar ataxia

in a large Kindred: Age at onset, reproduction, and

genetic linkage studies. Neurology 34:152-1548, 1984

Harding AE: The clinical features and classification of the late

onset autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: A study of

Il families, including descendants of The Drew family of

Walworth’, Brain 105:1-28, 1982

Hoffman PM, Sturat WH, Earle KM, Brody JA: Heriditary late-

onset cerebellar degeneration, Neurology 21:771-777,

1971

Jellinger k, Tarmowska-Dziduszko: Die ZNS-Veranderungen

bei den olivaponto-cerebellaren Atrophien. Z Neurol

199:192-214, 1971. cited from Berciano J.

Jeon 85, Roh JK, Myung H J: Three cases of olivopon-

tocerebellar atrophies. Kor Neurol Assoc 2:77-83, 1984

Konigsmark BW, Weiner LP: The olivopontocerebellar

trophies: A review. Medicine 49:227-241, 1970

Landis DM, Rosenberg RN, Landis SC, et alt Olivopon-

tocerebellar degeneration: clinical cand ultrastructural ab-

normalities. Arch Neuro! 31:295-307, 1974

Lee KS, Sunwoo IN, Kirn 5, Kim KW: Clinical Study of pon-

tocerebellar atrophy base on CT brain scan. J Kor Neurol

Assoc 3:40-48, 1985

Lim Sk, Sunwoo IN, Kim KW: A family of hereditay olivopon-

tocerebellar atrophy: Menzel type OPCA, OPCA Il with

retinal degeneration. J Kor Neurol Assoc 2:77-83, 1984

Platakis A, Nicklas WJ, Desnick Rj: Glutamate dehydrogenese

deficiency in three patients with spinocerebellar syn-

drome. Ann Neurol 7:297:303, 1980

Pratt RTC: The genetics of neurological disorders, Oxford

University Press, London, 1967, 37

Rosenhagen H: die Primare Atrophie des Brickenfusses und

der unteren Oliven (dar gestellt nach klinischen und

anatomischen Beobachtungen). Arch Psychiat Nervenkr

116:163-228, 1943. cited from Berciano J.

Rowland LP: Merritt's textbook of neurology. 7th ed. Lea &

237

Mt Saing Choi et al

Febiger, Philadelphia, 1984, 499547 ° ‘Ann Neurol 19:239-245, 1986

‘Schut J, Haymaker W: Hereditary ataxia clinical study through, “Thilenius OG, Grossman Bf: Friedreich's ataxia with heart

six generations. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 63:535-568, 1950 disease in children. Pediatrics 27:246-254, 1961

Sorbi S, Tonini 5, Giannini E, et af: Abnormal platelet Vietor M, Adams RD, Mancall EL: A restricted form of

glutamate dehydrogenase activity and activation in domi- cerebellar cortical degeneration occurring in alcoholic

nant and nondominant olivopontocerebellar atrophy. patients. Arch Neurol 1:579-568, 1959

238 Volume 29

También podría gustarte

- Desviaciones A La Ley de BeerDocumento2 páginasDesviaciones A La Ley de BeerMarthaMorales100% (1)

- Propiedades Electricas y SemiconductoresDocumento40 páginasPropiedades Electricas y SemiconductoresMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Mediciones en QuimicaDocumento24 páginasMediciones en QuimicaMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Me TodosDocumento1 páginaMe TodosMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Carolina Saracho: C++ (Pronounced Cee Plus Plus, / SiDocumento1 páginaCarolina Saracho: C++ (Pronounced Cee Plus Plus, / SiMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Estructuras cristalinas, parámetros reticulares y diagramas de difracciónDocumento18 páginasEstructuras cristalinas, parámetros reticulares y diagramas de difracciónmario alexisAún no hay calificaciones

- ExtrusionDocumento67 páginasExtrusionMiroosslava MendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Metales y Aleaciones Ferrosas - Secc3 - Mtto para Expo RodoDocumento17 páginasMetales y Aleaciones Ferrosas - Secc3 - Mtto para Expo RodoMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Cerveza artesanal JaliscoDocumento86 páginasCerveza artesanal JaliscoMartin Emmanuel Cueva Lopez86% (7)

- Cristal EsDocumento37 páginasCristal EsMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Solucionario Denis Zill, Capitulo de Números ComplejosDocumento22 páginasSolucionario Denis Zill, Capitulo de Números ComplejosRodrigo Figueroa100% (3)

- Teoria de Colas2Documento14 páginasTeoria de Colas2MarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- 2000 2012 PDFDocumento7 páginas2000 2012 PDFgallito6Aún no hay calificaciones

- Los componentes de la sangreDocumento25 páginasLos componentes de la sangreCarlos Cayulef UlloaAún no hay calificaciones

- Nucleación ExtendidaDocumento3 páginasNucleación ExtendidaMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- TesisDocumento79 páginasTesisMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Sistema Inmune-CelulasDocumento10 páginasSistema Inmune-CelulasAngel CAún no hay calificaciones

- Metales y Aleaciones Ferrosas - Secc3 - Mtto para Expo RodoDocumento17 páginasMetales y Aleaciones Ferrosas - Secc3 - Mtto para Expo RodoMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Aem 6Documento24 páginasAem 6Matt CosentinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Propiedades Electricas y SemiconductoresDocumento40 páginasPropiedades Electricas y SemiconductoresMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Conductividad TérmicaDocumento2 páginasConductividad TérmicaMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- PATENTEDocumento18 páginasPATENTEMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Operación Microsoft ExcelDocumento2 páginasOperación Microsoft Excelcarolina_schnyder100% (1)

- Uso de Excel en Registros y ComandosDocumento1 páginaUso de Excel en Registros y ComandosMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Articulo AbsorciónDocumento9 páginasArticulo AbsorciónMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Notas Anova1 ExcelDocumento2 páginasNotas Anova1 ExcelJkhkhkjhj SffsfsAún no hay calificaciones

- Tipos de EquilibrioDocumento2 páginasTipos de EquilibrioMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Notas Anova1 ExcelDocumento2 páginasNotas Anova1 ExcelJkhkhkjhj SffsfsAún no hay calificaciones

- Habilidades DirectivasDocumento1 páginaHabilidades DirectivasMarthaMoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)