Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Urban 2

Cargado por

David Lagunas AriasTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Urban 2

Cargado por

David Lagunas AriasCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp.

926946, 2001

2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved

Printed in Great Britain

0160-7383/01/$20.00

www.elsevier.com/locate/atoures

PII: S0160-7383(00)00082-7

AN INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORK

FOR URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

Douglas G. Pearce

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Abstract: This paper outlines an integrative framework for urban tourism and illustrates

applications with reference to selected aspects of the literature. The framework emphasizes

the identication of subject cells within a matrix dened in terms of scale (site, district, city-

wide, regional, national, and international) and themes (demand, supply, development, and

impacts). It stresses the need to examine the relationships between these, both vertically and

horizontally. This is offered as a means of providing a more systematic and coherent perspec-

tive on urban tourism, as a way of integrating a steadily growing but as yet largely fragmented

body of research and providing structure for future efforts in this eld, both conceptually

and empirically. Keywords: urban tourism, frameworks, linkages, cities, tourism districts, glo-

balization. 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Resume: Un schema dintegration pour les recherches sur le tourisme urbain. Cet article

expose les grandes lignes dun schema dintegration pour les recherches sur le tourisme

urbain et en illustre des applications en se reportant a` certains aspects de la litterature. Ce

schema souligne lidentication de cellules de sujet dans une matrice qui est denie en

fonction dechelle (site, quartier, ville, region, nation, monde) et de the`mes (demande, offre,

developpement, impacts). On accentue le besoin dexaminer verticalement et horizontale-

ment les rapports entre les elements de la matrice. Ce schema pourrait offrir une perspective

plus systematique et coherente sur le tourisme urbain, integrer une importante bibliographie

qui continue a` saccro tre tout en restant en grande partie fragmentaire et fournir une struc-

ture pour des recherches futures dans ce domaine a` partir des points de vue conceptuel

et empirique. Mots-cles: tourisme urbain, schemas, rapports, villes, quartiers touristiques,

mondialisation. 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION

Urban tourism has emerged as a signicant and distinctive eld of

study during the 90s. Earlier work, dating back to the 60s, was sporadic

and limited in scope, much of it being carried out by geographers

(Gutierrez-Ronco 1977; Jansen-Verbeke 1986; Liu 1983; Pearce 1981;

Stanseld 1964; Vetter 1974). The past decade has seen increased

attention throughout the world from both tourism researchers and

urban studies specialists alike, from Europe (Cazes and Potier 1996,

1998; van den Berg, van der Borg and van der Meer 1995) to North

Douglas Pearce is Professor of Tourism Management (School of Business and Public Man-

agement at Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand. Email

<douglas.pearce @vuw.ac.nz>). He has published widely on many aspects of tourism. This

includes three books on Tourist Development; Tourism Today: A Geographical Analysis; and Tourist

Organizations, as well as three co-edited volumes on Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges;

Change in Tourism: People, Places, Processes; and Contemporary Issues in Tourism Development.

926

927 DOUGLAS PEARCE

America (Judd and Fainstein 1999; ONeill 1998), and from Africa

(Marks 1996) to Asia (Teo and Huang 1995; Chang and Yeoh 1999).

This increase in attention in part reects the growth of tourism in

cities and its resulting associated policy issues. These tend to be of

two main types. On the one hand, the growing demand from tourists,

particularly in historic cities, has brought a reactive response arising

from the problems of coping with increased visitation, a situation per-

haps most commonly experienced in Europe (van der Borg 1998). On

the other, many urban policies have recently incorporated an increas-

ingly proactive stance towards tourism which is seen more and more

as a strategic sector for urban revitalization in post industrial cities

(Jansen-Verbeke and Lievois 1999; Judd and Fainstein 1999). This

economic emphasis has often brought with it the belated recognition

that cities are indeed major destinations or, if not now, they may have

the potential to become so. Cazes, however, argues that instead of see-

ing urban tourism as a recent phenomenon, it is, on the contrary,

the remarkable permanence of the attractiveness of cities that should

be underlined (1994:27).

While the sheer volume of studies now appearing contributes to the

identication of urban tourism as a distinctive eld and the term is

often used without question or justication, others have sought to clar-

ify this concept (Ashworth 1992; Marchena Gomez 1995). In determin-

ing whether there is an urban tourism, Ashworth (1992) emphasizes

two interrelated sets of factors: the setting and the associated activities

that occur there. The latter and Blank (1994), Marchena Gomez

(1995), Pearce (1995), and others stress that urban areas are distinctive

and complex places. Four commonly accepted qualities of cities are

high physical densities of structures, people, and functions; social and

cultural hetereogeneity; an economic multifunctionalism; and a physi-

cal centrality within regional and interurban networks. When cities are

considered as settings in which tourism develops, this complexity is

inextricably melded into the structure and nature of urban tourism,

giving it characteristics which set it apart from other, particularly

resort-based, forms in coastal or alpine environments. In cities, tourism

is but one function among many, with tourists sharing and/or compet-

ing with residents and other users for many services, spaces, and ameni-

ties. Moreover, a city may have multiple and overlapping tourism roles:

as a gateway, staging post, destination, and tourist source (Pearce

1981).

As for activities, the attractiveness of urban destinations according to

Karski lies in the rich variety of things to see and do in a reasonably

compact, interesting, and attractive environment, rather than in any

one component. It is usually the totality and the quality of the overall

tourism and town center product that is important (1990:16).

Erhlich and Dreier make the same point specically visitors are

drawn to Boston for the completeness of its urban ambience: the

vitality of its newer developments blend with the richness of its histori-

cal and cultural attractions, architectural delights, interesting shopping

venues, restaurants, theatres and night clubs (1999:161). The demand

928 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

for urban tourism is thus multidimensional and frequently multipur-

pose in nature.

The complexity of urban tourism has no doubt helped delay

research in this eld, because the need to disentangle it from other

urban functions makes it more difcult to study than in many other

settings. The complexity of the setting and associated activities also

results in a continuing problem with urban tourism studies, namely

that of incompleteness and limited coverage. According to Blank,

most urban tourism studies investigate only parts of the traveler

pattern. Partial studies lead to widespread misunderstanding of urban

tourism. As a serious consequence, many urban leaders give the tour-

ism industry less support than if its full role and scope were more

clearly dened. Further, market studies, which must often be limited

in scope, are best undertaken in full knowledge of the total market

(1994:184185).

However, it is not only for practical and policy matters that a more

systematic and comprehensive approach to urban tourism is needed:

A specically urban tourism requires the development of a coherent

body of theories, concepts, techniques and methods of analysis which

allow comparable studies to contribute towards some common goal

of understanding of either the particular role of cities within tourism

or the place of tourism within the form and function of cities

(Ashworth 1992:5).

While special issues of journals and books on urban tourism have pro-

vided some structure to this emerging eld, there is still a considerable

way to go in terms of developing a coherent corpus of work, pursuing

common goals and carrying out comparable studies. The tourism and

urban studies literatures scarcely overlap; considerable scope exists for

improving the linkages among the work being done in Europe, North

America, Asia, and elsewhere, and much effort continues to be

expended on fragmented, ideographic research.

This complexity, fragmentation, and lack of coherence calls for a

clear, analytical framework which provides a more systematic perspec-

tive on urban tourism issues. It should offer both a general overview

of the eld and a means of putting specic studies and problems in

context, so as to understand better the existing interrelationships, to

develop a sense of direction and common purpose, and to provide

more integrated solutions to problems which may arise. The purpose

of this paper is to outline such a framework and to illustrate its appli-

cation with reference to selected aspects of urban tourism research.

AN INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORK

An analytical framework might be thought of as a set of relation-

ships that do not lead to specic conclusions about the world of events

but can serve in organizing in a preliminary way the object of the

inquiry (Pacquet 1993:274). Frameworks can take a variety of forms.

A good framework provides structure but does not act as a straitjacket.

929 DOUGLAS PEARCE

The framework outlined in Figure 1 consists of a matrix in which the

two axes are the themes to be considered and the scale at which this

consideration takes place. Although they may vary in detail and charac-

ter, the key themes to be addressed in cities are common to tourism

elsewhere and will not be examined further at this stage. They include

demand, supply, development, marketing, planning, organization,

operations, and impact assessment. Likewise, spatial scale may be used

to order tourism themes in a variety of contexts, with the range of

scales to be included depending on the problem in question.

In this regard it should be recalled that scales are constructs, ways

of conceptualizing space, rather than existing, xed realities. Here,

spatial scale is a particularly appropriate ordering device as the nature

of the theme may vary from one scale to another along with changes

in responsibility for policymaking, management, operations, and other

practical applications. Moreover, as Ashworth and Voogd assert, scale

becomes crucial if destinations are considered as places:

A place is inevitably one component of a hierarchy of spatial scales.

This is more than the inevitable parochial viewpoint of a geographer

accustomed to hierarchical spatial modeling: it is central to the nature

of the tourism product and how it is marketed (1990:8).

The examination and eshing out of individual cells within the matrix

needs to be complemented by more integrative approaches which sys-

tematically examine linkages both horizontally (that is, which integrate

different themes at the same spatial scale) and vertically (that is, which

examine a theme across two or more spatial scales). From one perspec-

tive, questions of thematic or scale linkages might be seen in terms of

approaches to research or management. Whatever the scale of analysis,

the most common approach to date has been to adopt a supply-side

focus based on inventories of tourism product, usually accommo-

dation, sometimes attractions and transport and, more rarely, a combi-

nation of various elements (Pearce 1998a). Greater understanding will

result when supply-side data are complemented by information on

demand and consumption. Similarly, comprehensive tourism planning

Figure 1. An Integrative Framework for Urban Tourism Research

930 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

will need to incorporate marketing and development as well as con-

sideration of other themes such as organizations and impacts.

At the same time, considerable scope exists for multiscale examin-

ation of a range of themes. Studies of the demand for urban tourism,

for example, have been limited, by the ready availability of appropriate

data, usually to city-level statistics. However, data sources may also exist

at larger and smaller scales. Systematic compilation of a diverse range

of secondary sources, from surveys which set the city in a broader

national and regional context, through city-wide bednight gures to

the results of tourist monitoring at individual sites, has enabled a much

more comprehensive picture of the demand for urban tourism in Paris

to be established (Pearce 1996a). Here diverse data already existed,

but in the absence of an integrative approach little holistic analysis had

been undertaken. Similarly, tourism plans at a variety of scales from

the metropolitan area, through districts such as Montmartre to sites

on the Ile de la Cite have been prepared, but these have essentially

been isolated efforts with little overall coordination between actions at

different scales and in different parts of the city (Pearce 1998a, 1998b,

1999). Impact assessment is another theme that would benet greatly

from an integrated multiscale approach. Surveys may indicate overall

patterns of expenditure but rarely is there any breakdown on where

that spending occurs within the city and who the beneciaries are

(Parlett, Fletcher and Cooper 1995). Likewise, congestion may be a

problem at different scales, from pressure on landing slots at regional

airports to queuing within historical buildings.

From a second but related perspective, relationships might be

explored in terms of who or what constitute the links between scales

or themes. That is, having decided to examine a problem across several

scales or to bring together different themes, how is this to be done?

How are the linkages to be conceptualized and measured? Concep-

tually, relatively little work of this sort has been undertaken with regard

to urban tourism, but use of broader theories and approaches such as

interorganizational analysis (Pearce 1992), globalization and localiz-

ation (Chang 1999), and more general concepts such as gateways

(Burghardt 1971) and hubs (Fleming and Hayuth 1994) provide useful

examples of what might be done and signal fruitful paths to follow.

In terms of measurement, Smith and Timberlake (1995) distinguish

between two dominant methodological strategies in their analysis of

the world city system: the attributional strategy based on the attributes

of cities and the linkage-based strategy which employs data that directly

link cities to one another or to a larger entity such as the world system.

They indicate that the former has been the most common, but argue

that attributional data are only circumstantial when the theories

employed stress relationships among places. The distinction between

the attributional and linkage-based strategies is a potentially very useful

one for operationalizing the connections in Figure 1. Smith and Tim-

berlakes experience suggests, however, that difculty is likely to be

encountered in collecting relevant relational data.

Several potentially useful but as yet largely unexplored lines of

enquiry exist here. First, detailed examination of tourist behavior as

931 DOUGLAS PEARCE

they arrive in a city, travel around within it, and visit particular sites

will provide insights into the ways in which particular places are linked

together, of how tourism districts function (or not), and what interac-

tion occurs. The density and complexity of the urban environment

pose many challenges to researchers in attempting to record

movements and monitor behavior, but use of innovative method-

ologies provides some ways forward as Hartmann (1988), Murphy

(1992a), and Dietvorst (1994) have shown. For example, Hartmanns

use of multiple techniques (interviewing, participant and non-partici-

pant observation), provides some interesting insights into tourist

behavior in Munich while also highlighting the practical and ethical

difculties which can arise with such eldwork. Second, questions of

external and internal accessibility and the provision of transport infra-

structure and services to and within the city are major issues yet ones

which have largely been neglected from a tourism perspective (Page

1995). Third, the commercial linkages and operational arrangements

among providers of services and amenities at different scales and in

different parts of the city must be examined. Jansen-Verbeke and Ash-

worth (1990) provide some useful concepts in this regard, but these

need operationalizing and empirical testing. Fourth, administrative

and organizational roles and responsibilities at different scales need to

be clearly established and attention directed at how effectively various

agencies and organizations come together to develop, promote, or

otherwise facilitate urban tourism (Pearce 1992).

As an analytical framework, Figure 1 enables researchers to establish

systematically what is already known about urban tourism, either for a

particular place or (more generally) to identify gaps in present knowl-

edge and determine more readily what the issues are. Given the

recency of research on this subject, it is likely that in most places the

gaps will exceed what is already known. Use of this chart might

enhance the value of existing work by enabling it to be put into a

broader context and by acting as a framework to develop cumulative

knowledge about urban tourism in general or with regard to problems

associated with other types in a specic town or city. For instance, at

a very basic level, Figure 1 may enable a systematic cataloguing of exist-

ing studies and inventorying of current data sources. At the same time,

it should assist in identifying more clearly where future effort might

be directed and how the different parties involved might come

together more effectively. Likewise, a more integrated approach to

planning and managing urban tourism is called for. In this respect,

the application of the chart may assist in showing the range of issues

and parties involved while the emphasis on linkages highlights the

need for coordination and cooperation between scales and different

themes. What connections are there, for example, among those agenc-

ies, organizations, and individuals responsible for promoting the city,

planning transport infrastructure, managing various attractions, and

operating tourism businesses?

Therefore, as an analytical framework, Figure 1 is offered very much

as a point of departure, as a way of facilitating further work on urban

tourism, rather than as an end-point to be achieved. The ways in which

932 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

it might be applied thematically have been outlined briey above by

reference to such themes as demand, planning, and impact assessment.

The application of the framework as an integrative device and as a tool

for identifying research questions would become more illustrative by

systematically reviewing aspects of the literature on urban tourism in

terms of spatial scale.

A Spatial Application

So far most work on urban tourism has been conned to analyses

at a single spatial scale, commonly tourism in the city as a whole, but

analysis at a range of scales that includes the relationships among them

is essential if a comprehensive picture of urban tourism is to be

developed. The following sections consider in varying detail issues

which arise at the four scales depicted in Figure 1, beginning with

those within the city before considering linkages at a larger scale.

City-Level. Much of the initial research on urban tourism has con-

sisted of general studies and overviews of individual cities or groups

of cities. Here the city is the focus or unit of analysis, and aggregate

data are often used to establish the basic characteristics and general

features of tourism. Two main types of city-level research can be ident-

ied: single city and multiple city studies.

Single city studies tend either to deal with tourism in general (Law

1996; Obiol Menero 1997) or to examine some particular aspect of it,

such as the distribution of accommodation (Oppermann, Din and

Amri 1996; Timothy and Wall 1995) and policy matters (Lopez Palo-

meque 1995). Most city-specic studies adopt a largely empirical

approach, with the emphasis commonly being on describing tourism

in the focal locality rather than using the situation there to address

questions of a more general nature. In their generality they provide

one form of integration by bringing together different aspects of tour-

ism in an urban setting, but the failure to make links with other cities

or broader questions limits their ability to advance the understanding

of urban tourism as a whole. Interesting exceptions to this pattern

include the studies by Cohen (1997) and Atkinson (1997) who use the

examples of Liverpool and New Orleans to examine the relationships

between tourism and popular music. Another is the volume edited by

van den Berg et al (1995) which concludes by synthesizing eight case

studies of European cities with regard to policy and successful urban

tourism products.

In contrast, multiple city studies tend to be more narrowly focused

and examine a specic aspect of a broader problem in a systematic,

comparative fashion. Thus, ONeill (1998) sought to identify the fac-

tors that characterized three United States municipalities recognized

as having effective and innovative tourism and convention bureaus,

while Gilbert and Clark (1997) compared the impact of tourism in two

urban centers that differed in their levels of arrivals. Other compara-

tive studies have adopted a more quantitative approach, examining

specic attributes of tourism among larger groups of cities, for instance

933 DOUGLAS PEARCE

markets and competition (Mazanec 1995) or social structure

(Gladstone 1998).

Tourist Districts. Studies of more specic areas within the city are

needed for two reasons. First, tourism does not occur evenly or uni-

formly, but is concentrated in particular areas that warrant research

in their own right. Second, more detailed analyses requiring a nar-

rowing of the lens and a concentration on problems at a smaller spatial

scale are needed to develop a fuller understanding of patterns, pro-

cesses, and interrelationships, as well as to adopt a greater multidimen-

sional approach to urban tourism.

The clustering of tourism facilities has been observed for some time

and descriptive accounts of districts, especially in historic cities, are

not uncommon at the city level (Obiol Menero 1997; Priestley 1996),

but to date district level studies have scarcely been recognized as a

distinctive research problem (Pearce 1998a). The existence of differ-

ent types of district reects two of the dening attributes of cities noted

by Ashworth (1992): social and cultural hetereogeneity and economic

multifunctionalism. It is also a function of the specic characteristics

of individual cities and a range of promotional and development stra-

tegies. An initial classication might include six types of districts, not

necessarily mutually exclusive.

One: Historic Districts. The old city and historic nuclei have for

some time been recognized as important districts in many cities, parti-

cularly in Europe, attracting tourists through a compact clustering of

interesting buildings, monuments, and museums, often readily access-

ible on foot. Much of the initial research in this area is associated with

the work of Ashworth (1990) and Ashworth and Tunbridge (1990),

whose touristic-historic city model has been used as the basis for other

studies of this type. In an account of the Dutch city of Groningen,

the former underlines the notion of districts as constructs, identifying

several forms of historic city (or district) depending on the perspective

adopted: the architect/historians, the legislative, the urban planners

and managers and the touristic historic city. Drawing on discourse

analysis and Urrys notion of the tourist gaze, Dahles shows how two

different images of the historic inner city of Amsterdam have been

constructed: one for the international tourist based on the tokens

of the remembered empire, a second more local discourse that

reects a middle-class preoccupation with folklore, oral tradition, local

history, but also with welfare and resettlement programmes (Dahles

1996:230). In a completely different context, Teo and Huang trace the

creation of the Civic and Cultural District in Singapore, showing how

its conservation as a rich, historical area was predicated on the argu-

ment that it lies astride the tourism retail belt of Orchard Road

and the convention core of the Marina center (1995:599). In the

United States, theming of historic retail districts has become a wide-

spread strategy in many cities to attract both tourists and shoppers

(Ehrlich and Dreier 1999; Lew 1989). As the growth in heritage tour-

ism intensies, historic districts will attract more attention.

Two: Ethnic Districts. Districts associated with particular ethnic

934 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

groups have also been promoted and developed in various ways as

attractions. Conforti (1996) identies different processes and out-

comes in terms of the Little Italies of American cities. The one in New

York city represents the conscious preservation of a ghetto as an attrac-

tion, proximity to other attractions is a critical factor in Baltimore and

Boston, while in south Philadelphia the lack of appeal to tourists is

partly a function of its out-of-the-way location and absence of a vivid

image.

Perhaps the most explicit and concerted use of ethnic districts for

tourism is to be found in Singapore. There the tourism board, in

association with the urban planning authority, has consciously sought

to exploit the citys multicultural heritage under the slogan Instant

Asia, by theming, conserving, and promoting a number of ethnic and

historic districts, including Chinatown, Little India, and the Malay

Kampong Glam (Chang 1997, 1999; Chang and Yeoh 1999; Teo and

Huang 1995; Yeoh and Huang 1996). These Singaporean writers pro-

vide very detailed and insightful accounts of the processes at work,

from the underlying ideology to the physical and promotional aspects

of theming, and the resultant outcomes, interpreting these from a var-

iety of theoretical perspectives.

Three: Sacred Spaces. Distinctive districts are also to be found in

pilgrimage cities. Schachar and Shoval outline a complex pattern of

sacred spaces in Jerusalem, asserting that the city

rather than containing a single tourism district, encompasses a con-

stellation of spaces, each of which is composed of sites specic to a

particular group of pilgrims and tourists. In addition, a small number

of sites are visited because of their universal appeal, which transcends

their specic religious, cultural or national signicance.

This spatial segmentation

has been a highly political process, molding the entire urban fab-

ric (1999:201).

Even where a single religion prevails, as at Lourdes, pilgrims may con-

centrate in very specic parts of the city, with differences occurring

between group and individual travelers depending on their different

needs and characteristics (Chadefaud 1981).

Four: Redevelopment Zones. With tourism increasingly being used

as a strategy for economic revitalization, tourism services and facilities

are progressively being incorporated into redevelopment zones, parti-

cularly in waterfront areas, as in Amsterdam, Baltimore, and Londons

Docklands (Jansen-Verbeke and van de Wiel 1995; Page 1995). It is in

this context and that of intercity competition that Judd refers to the

remaking and reshaping of parts of many American cities as well-

dened and spatially separate tourist bubbles:

Where crime, poverty and urban decay make parts of a city inhospi-

table to visitors, specialized areas are established as virtual tourist res-

ervations. These become the public parts of town, leaving visitors shi-

elded from and unaware of the private spaces where people live and

work (1999:36).

935 DOUGLAS PEARCE

Such spaces, he suggests, have quickly become standardized venues

featuring a mayors trophy collection of an atrium hotel, festival mall,

convention center, restored historical neighborhood, domed stadium,

aquarium, new ofce towers, and redeveloped waterfront.

Five: Entertainment Destinations. Sassen and Roost argue that large

modern cities have become sites of consumption, they have

assumed the status of exotica, and that modern tourism is centered

on the urban scene, or more precisely, on some version of the

urban scene t for tourism. One consequence of this has been the

development of urban entertainment destinations, such as midtown

Manhattan, in which are concentrated entertainment-oriented

retailers, high-tech entertainment centers, cinema complexes, and

themed restaurants (1999:143).

Six: Functional Tourism Districts. Other researchers, less concerned

with the form of specic types of districts, have been more interested

in ways particular parts of cities function as such and in examining the

intersectoral linkages, both spatial and functional, which have emerged

at that level. Getz (1993), drawing on Stanseld and Rickert (1970),

developed a schematic model of a Tourism Business District, the

essence of which is

a synergistic relationship between CBD [Central Business District]

functions, tourist attractions, and essential services. Access into and

within the CBD is critical . The synergy must not only create a criti-

cal mass of attractions and services to encourage tourists to stay longer

(preferably overnight) but must reinforce the image of a people-ori-

ented place (1993:597).

Likewise, Judd emphasizes the agglomerative nature of the compo-

nents making up a tourist place (1993:179). Jansen-Verbeke and Ash-

worth contend that [s]uccess depends upon the functional inte-

gration within multipurpose clusters, which necessitates more attention

being paid to the nature of integration (1990:619). They then go on

to propose a set of different combinations of spatial association and

functional linkages. Originally conceptual in nature, these studies are

now being complemented by efforts aimed at developing method-

ologies for identifying functional districts (Jansen-Verbeke and Lievois

1999) and other detailed empirical work. Pearces (1998a) research

on three different tourism districts in Paris, for example, has shown a

certain level of synergy exists but that the functional association

between major and other attractions is not as strong as physical prox-

imity alone might otherwise suggest. This study also reveals a varying

degree of compatibility between tourism and other urban functions

across the city.

Considerable scope exists for bringing these different approaches

together. For example, Teo and Huangs (1995) account of how Singa-

pores Civic and Cultural District was created might usefully be comp-

lemented by how it actually functions. The authors observations there

suggests that while much infrastructural development is occurring and

the district has been themed, complete with designated itineraries,

storyboards, and other markers, it has yet to function fully as a tourism

936 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

district. Most of the activity appears at present to occur on the fringes

of the district. Sightseeing coaches are parked in Connaught Drive to

discharge their passengers who quickly make their way in groups to

photograph the sculpture of the Merlion, the created image of Singa-

pore, with relatively few venturing further into the district to admire

its colonial past. More generally, the ways in which the different dis-

tricts are linked together, whether by tourist ows or marketing

activity, deserves much closer attention if this function of cities is to

be fully understood (Pearce 1998a).

Tourist Sites. Research at the scale of more localized sites has basi-

cally been neglected, but is no less critical. For example, it is at this

level of the individual attraction that many of the tourists experiences

are played out, their levels of satisfaction determined, various impacts

are felt, and many management and planning issues arise. Individual

features constitute the basic building blocks on which urban tourism

is founded, and understanding what happens at this scale is essential

for a fuller comprehension of tourism in the city as a whole (Pearce

1999). Work on individual sites has usually taken the form of architec-

tural or planning studies or tourist monitoring. However, more general

issues may also be addressed at this scale, such as exploring the notion

of what constitutes a tourism place, how space at the microscale is

modied and managed, and how competition in the use of space

occurs between hosts and guests.

Regional/National/International. For a fuller understanding of this

form of tourism, urban areas also have to be set in a broader geo-

graphical context with issues being explored at a regional, national,

and international level. This scale of analysis is important both from

the point of view of tourism, particularly when considering the func-

tions of cities other than those of a destination (Pearce 1981), and

from a broader urban perspective, notably in terms of the notion of

centrality mentioned by Ashworth (1992). As with tourism districts, this

is not as yet a readily recognizable eld of study. But among the frag-

mented literature two broad and largely unrelated approaches are dis-

cerned, one primarily concerned with functional issues, the other with

a more theoretical interpretation linked to processes of globalization

and local responses.

One: Functional Roles and Linkages. Cities, especially large metro-

politans, in addition to existing as destinations in their own right, are

also recognized as having other functions in broader regional,

national, or even international systems, notably as gateways (Low and

Toh 1997; Pearce 1981) and, more recently, hubs (OKelly and Miller

1994). These terms, though used much more frequently, still require

elaboration and development, both conceptually and operationally, to

become effective tools for the analysis of urban tourism at such

larger scales.

Gateways in a general sense are seen as major entry/exit points for

tourists into or out of a national or regional system (Pearce 1995).

Burghardts (1971) seminal paper in the broader geographical litera-

937 DOUGLAS PEARCE

ture outlines four key attributes of gateway cities. One, they are in

command of the connections between the tributary area and the out-

side world and develop in positions which possess the potentiality

of controlling the ows of goods and people. Two, they often develop

in the contact zones between differing intensities or types of pro-

duction. Three, although local ties are obviously important, gateways

are characterized best by long distance trade connections. Four, they

are heavily committed to transportation and wholesaling (1971:282).

Work is now needed on determining the tourism dimensions of

these general attributes. What, for example, is the role of tour whole-

salers, both inbound and outbound, in gateway cities? In what ways

and to what extent do their channels of distribution control such ows?

How do the buyersupplier relationships for urban tourism compare

with resort-based types (March 1997)? Renucci (1992), for instance,

shows that very few Italian tour operators include Lyon in their cata-

logues; when they do, such visits are limited to a rapid tour of the city.

Britton (1982), Pearce (1984), and Zurick (1992) have examined the

intermediate role of tourism gateways in such peripheral destinations

as the South Pacic, Belize and Nepal. Yuan and Christensen (1994)

and Ewert (1996) have considered the functions of portal communi-

ties in areas adjacent to natural landscapes. To date, little research

on tourism gateways and hubs has been carried out in the metropolitan

areas of Europe and North America. Pearce (1996b) has commented

on the gateway role of Stockholm, for example in terms of information

provision and linkages with other destination regions such as Lapland

and Gotland. But in general these issues are as yet unexplored.

Recent related work in Europe and North America has come out of

the eld of transport studies and focused more on the concept and

operations of airport hubs, with an emphasis on their transfer func-

tions within a wider network (Dennis 1994; Fleming and Hayuth 1994;

OKelly and Miller 1994; OKelly 1998). For the latter, hubs are

special nodes that are part of a network, located in such a way as to

facilitate connectivity between interacting places (1998:171). This is

achieved by the construction of a network where direct connections

between all origin and destination pairs can be replaced with fewer

indirect connections (OKelly and Miller 1994:31). Again, the tourism

dimensions of hubs and hubbing need further explication. As an illus-

tration of their agglomeration effects, OKelly (1998) suggests that a

hub increases a citys ability to attract conventions and business meet-

ings.

Operationalizing these concepts from a tourism perspective requires

more than the analysis of routes, services, and airline networks that

underpin the work of transport specialists. Particular attention must

be given to the various ways of analyzing travel patterns, as these form

one of the most direct and tangible links among cities and other areas

(Pearce 1995). In Smith and Timberlakes (1995) terms, they consti-

tute an especially relevant relational measure. The Trip Index, which

relates the proportion of nights spent in any one place to the total

length of the trip, can be a useful means of measuring the intermediate

role of cities (Murphy 1992b; Oppermann 1992; Pearce and Elliott

938 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

1983). Murphy, for example, identied a hierarchical spatial pattern

on Vancouver Island based on its two principal gateways. Similarly, sur-

vey data of international tourists in Paris indicates how a visit to the

city ts into a broader pattern of travel (Pearce 1996a). Europeans

have a greater tendency to make Paris the sole focus of their trip than

longer haul tourists from Japan and the United States. For many

Japanese, Paris is one stop on a tour of European cities, with few other

French regions being visited.

Other functional linkages among cities, surrounding regions, and

other areas have been examined by way of interorganizational analysis

in the broader context of the study of the structure and functioning

of tourism organizations at different scales (Pearce 1992). What this

research shows is that different sorts of linkages may exist among them

(voluntary or mandated, top down/bottom up, unifunctional or multi-

functional, cooperative or competitive) and that different sorts of

relationships are found. Some urban entities recognize a functional

interdependence with their surrounding regions and often play a lead-

ership role in marketing and development. In other instances, metro-

politan areas may opt out of joint participation and go it alone on the

grounds that their markets and industry structure differ or that joint

activities and combined decision-making lessen their ability to respond

quickly and exibly to changing conditions.

In the case of Barcelona, Lopez Palomeque (1995) shows how the

over-supply of accommodation in Barcelona following the 1992

Olympic Games led to increased interorganizational activity, both

within the city and between the city and the coastal regions of Cat-

alonia. Barcelonas regional gateway role has generally been rather lim-

ited due to the existence of more direct connections to the Costa Brava

and Costa Daurada. In contrast, Singapore is increasingly seeking to

overcome its constraints as an urban destination by explicitly

developing its gateway functions and adopting a broader tourism

regionalization policy (Chang 1998; Low and Toh 1997).

Two: GlobalLocal Processes. Urban tourism has been used by a

number of authors to explore broader processes that have been exam-

ined from different theoretical perspectives and which stress the need

to set individual cities in a much larger geographical, economic, and

political context (Chang 1999; Chang, Milne, Fallon and Pohlmann

1996; Fainstein and Judd 1999; Roche 1992; Thorns 1997). In these

accounts, urban tourism is heavily contextualized in terms of broader

processes of the economic restructuring of post-industrial cities, glo-

balization, and localization. The emphasis here is on tourism as a form

of regeneration as cities seek to rebuild their economies following the

decline in their more traditional industrial base, with cities becoming

as much sites of consumption as of production. Moreover, with the

growth of an increasingly globalized and interdependent economy,

larger cities are seen as being in ever stronger competition with each

other. The development of facilities and services, together with the

accompanying promotion of a strong, distinctive image, is thus inter-

preted as one dimension of intercity competition and the growth in

place marketing in general. At the same time, the role of local forces

939 DOUGLAS PEARCE

and responses in mediating these more general processes is acknowl-

edged, with urban tourism serving as an example of patterns of interac-

tion at the globallocal nexus.

The nature, pattern, and outcomes of this globallocal interaction

have been variously portrayed. Thorns, for example, suggests that New

Zealands three main citiesAuckland, Wellington, and Christ-

churchhave each sought to develop their distinctiveness within

the gambit of the international tourism agenda by embarking on

different urban development programs (1997:206). Fainstein and Judd

observe that the globalization of mass tourism leads to an odd para-

dox: whereas the appeal of tourism is the opportunity to see something

different, cities that are remade to attract tourists seem more and more

alike (1999:1213). It is this remaking which has given rise to the

enclaves or tourist bubbles described by Judd (1999) mentioned earl-

ier. However, Fainstein and Judd also recognize that while generaliza-

tions might be made about the structure of the industry and its pro-

duct, variations in the impacts of tourism and its multiple

meanings, depending on type of tourism and context, call for an exam-

ination of individual cases (1999:16).

In insightful writings on tourism in Singapore, Chang (1999) and

Chang et al (1996) vigorously assert the role of local factors and pro-

cesses, arguing that both globalization and localization are occur-

ring simultaneously with the outcome being a conation of homogen-

izing and localizing inuences in places (1999:93). The various ways

in which this occurs are discussed with regard to the themed ethnic

districts outlined earlier. Thus, in the case of Little India, Chang con-

siders the government policies which have led to the theming and con-

servation of the district, as well as the subsequent impacts which have

been experienced, whether by locals and tourists or Indian and Chi-

nese merchants. In this instance the social, economic, and spatial struc-

ture at the district level, and even arguably at that of the site, may be

seen as the result of the interplay of different forces, from the inter-

national, through the regional to the local.

Additional studies shed light on these issues in other cities and con-

texts. Pearce stresses the importance of taking individual city features

into account. He found that public intervention in tourism develop-

ment in Paris was indirect and reactive and largely associated with

broader urban policies and practices, particularly those promoting the

image of Paris and fostering its wider inuence. In this latter regard,

the place promotion of Paris was seen to have a distinctive French

avor, being a long established practice and one which successive

heads of state, motivated by a powerful mix of national chauvinism,

and self-aggrandizement, have pursued with varying degrees of vigor

in the French capital (1998b:172173). Hoffmann and Musil

(1999) found that tourism and privatization have been inextricably

linked in both the transformation and the conservation of Prague.

They concluded that evidence from that city is mixed in terms of the

extent to which tourism has provided an entry point allowing trans-

national corporations and homogenized mass culture to overwhelm

local differences.

940 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

In the context of the historic Stone Town of Zanzibar, Marks

explores a similar mix of economic liberalization and the growth of

international tourism, and examines the links between tourism devel-

opment and urban conservation. He, however, is more concerned that

the process in its present form is in danger of becoming a mech-

anism of gentrication and marginalization and calls for a more par-

ticipatory approach (1996:267). A different set of international and

local factors comes through in Edgingtons analysis of Japanese real

estate investment in Canadian cities. In explaining their investment in

hotels and resorts in British Columbia, rather than ofce blocks in

Toronto, Edgington concluded this was shaped by a combination

of corporate locational perceptions and local conditions (1996:303).

Further detailed work of this sort in other cities and countries would

aid in understanding this more commonly occurring aspect of tourism

and globalization.

CONCLUSION

The analytical framework portrayed as Figure 1 emphasizes the

identication of subject cells within a matrix dened in terms of scale

and themes and stresses the need to examine the relationships among

these, both vertically and horizontally. It has been offered as a means

of providing a more systematic and coherent perspective on urban

tourism, as a way of integrating a steadily growing but as yet largely

fragmented body of research and providing some structure for future

efforts in this eld, both conceptually and empirically. The extent to

which the framework succeeds in doing this will be up to others to

judge. However, a number of conclusions might be drawn from the

initial discussion of the framework and the subsequent application

of it.

The paper has highlighted the need for a more systematic, multi-

scale approach to the study of urban tourism, with Figure 1 proving a

practical means of ordering issues and ideas and enabling a larger,

more coherent picture to emerge. City-level studies have been shown

to make a useful contribution in terms of establishing specic urban

characteristics and providing some integration across themes. They

constitute a useful platform for further research, but this scale of analy-

sis alone does not reveal all the complexities of urban tourism. A sys-

tematic review of a fairly disparate literature within the structure of

the chart has enabled various types of tourism districts to be identied

and some common interrelated threads to be discerned in terms of

their causal factors, structure, and functioning.

The integrative approach employed here has brought out common

features at the district level, scarcely perceived previously as a distinc-

tive subeld of study, and shown how such studies t into the larger

picture. Conversely, the quasi-absence of site-specic studies has drawn

attention to the paucity of work done at the microscale and underlined

the research gap that exists there. The focus on regional, national, and

international relationships has drawn attention to two sets of studies,

one largely functional, the other more theoretical. While some com-

941 DOUGLAS PEARCE

mon themes are emerging with the latter, notably in terms of globaliz-

ation and local responses, the various functional issues and approaches

outlined have until now not been seen as focusing on a general prob-

lem. Clearly scope exists for bringing these two strands closer together,

for the globallocal debate is also related to issues of centrality, inter-

mediacy, and functional linkages within a wider tourism network. The

interaction between global and local forces and processes further

underlines the value of adopting a multiscale approach to the analysis

and interpretation of urban tourism. The creation of some of the dis-

tricts examined, such as those in Singapore, was seen to be one out-

come of this interplay.

The more systematic and integrative approach fostered by the frame-

work has also permitted some progress to be made in pursuing Ash-

worths (1992) question of whether or not there is an urban tourism.

In particular, it has enabled some of the distinguishing characteristics

of this setting and the activities that occur there to be elaborated on.

The structured discussion of districts and regional, national, and inter-

national linkages, for instance, has underlined the impact of the social

and cultural hetereogeneity, economic multifunctionalism, and cen-

trality of urban areas and highlighted the ways in which these inuence

tourism in cities.

The greater concern with more general problems and issues among

the non city-level studies also suggests that it is at these scales that

Ashworths question might best be pursued. As an ordering device and

a means of focusing attention on the more general problems which

have been identied in this paper, Figure 1 may also facilitate a bridg-

ing of the gap between the tourism and urban studies literatures and

among work being undertaken in different parts of the world. This in

turn should further help elucidate the nature of urban tourism and

its impact on city structures and processes. At the same time, any focus

on general problems should not obscure the role which individual city

features have been shown to play in many of the studies cited.

Finally, the broader, more integrative approach to research on

urban tourism advocated here suggests more effort must be directed

at synthesizing existing studies, at creating broader research designs

involving diverse methodologies, at drawing on multiple data sources

and combining these in innovative ways, and at interpreting the sub-

sequent results through a variety of lenses. While all of this may not

be possible within a single study, more explicit recognition of where

that study ts into the bigger picture is likely to lead to greater returns

on the research undertaken.

AcknowledgementA preliminary version of this paper was presented at the International

Conference on Urban Tourism held in Zhuai City China in 1999.

REFERENCES

Ashworth, G. J.

1990 The Historic Cities of Groningen: Which is Sold to Whom? In Marketing

Tourism Places, G. Ashworth and B. Goodall, eds., pp. 138155. London:

Routledge.

942 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

1992 Is There an Urban Tourism? Tourism Recreation Research 17(2):38.

Ashworth, G. J., and J. E. Tunbridge

1990 The Tourist-Historic City. London: Belhaven.

Ashworth, G. J., and H. Voogd

1990 Can Places be Sold for Tourism? In Marketing Tourism Places, G. Ash-

worth and B. Goodall, eds., pp. 116. London: Routledge.

Atkinson, C. Z.

1997 Whose New Orleans? Musics Place in the Packaging of New Orleans

for Tourism. In Tourists and Tourism: Identifying with People and Places,

S. Abram, J. D. Waldren and D. V. L. Macleod, eds., pp. 91106. Oxford:

Berg.

Blank, U.

1994 Research on Urban Tourism Destinations. In Travel, Tourism and Hospi-

tality Research: A Handbook for Managers and Researchers, J. R. B. Ritchie

and C. R. Goeldener, eds., 2nd ed., pp. 181193. New York: Wiley.

Britton, S. G.

1982 The Political Economy of Tourism in the Third World. Annals of Tour-

ism Research 9:144165.

Burghardt, A. F.

1971 A Hypothesis about Gateway Cities. Annals of the Association of Amer-

ican Geographers 61:269285.

Cazes, G.

1994 A Propos du Tourisme Urbain: Quelques Questions Prealables et

Derangeantes. Cahiers Espaces 39:2630.

Cazes, G., and F. Potier

1996 Le Tourisme Urbain. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Cazes, G., and F. Potier, eds.

1998 Le Tourisme et la Ville: Experiences Europeenes. Paris: LHarmattan.

Chadefaud, M.

1981 Lourdes, un Pe`lerinage, une Ville. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud.

Chang, T. C.

1997 From Instant Asia to Multi-faceted Jewel: Urban Imaging Strategies

and Tourism Development in Singapore. Urban Geography 18:542562.

1998 Regionalism and Tourism: Exploring Integral Links in Singapore. Asia

Pacic Viewpoint 39:7394.

1999 Local Uniqueness in the Global Village: Heritage Tourism in Singapore.

The Professional Geographer 51:91103.

Chang, T. C., S. Milne, D. Fallon, and C. Pohlmann

1996 Urban Heritage Tourism: The GlobalLocal Nexus. Annals of Tourism

Research 23:284305.

Chang, T. C., and B. S. A. Yeoh

1999 New Asia-Singapore: Communicating Local Cultures through Global

Tourism. Geoforum 30:101116.

Cohen, S.

1997 More Than the Beatles: Popular Music, Tourism and Urban Regener-

ation. In Tourists and Tourism: Identifying with People and Places, S. Abram,

J. D. Waldren and D. V. L. Macleod, eds., pp. 7190. Oxford: Berg.

Conforti, J.

1996 Ghettos as Tourism Attractions. Annals of Tourism Research 23:830842.

Dahles, H.

1996 The Social Construction of Mokum: Tourism and the Quest for Local

Identity in Amsterdam. In Coping with Tourists: European Reactions to

Mass Tourism, J. Boissevain, ed., pp. 227246. Providence RI: Bergahn

Books.

Dennis, N.

1994 Airline Hub Operations in Europe. Journal of Transport Geography

2(4):219233.

Dietvorst, A. G. J.

1994 Cultural Tourism and TimeSpace Behaviour. In Building a New Heri-

tage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe, G. J. Ashworth and

P. J. Larkham, eds., pp. 6989. London: Routledge.

943 DOUGLAS PEARCE

Edgington, D. W.

1996 Japanese Real Estate Investment in Canadian Cities and Regions 1985

1993. Canadian Geographer 40(4):292305.

Ehrlich, B., and P. Dreier

1999 The New Boston Discovers the Old: Tourism and the Struggle for a Liv-

able City. In The Tourist City, D. R. Judd and S. S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 155

178. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Ewert, A. W.

1996 Gateways to Adventure Tourism: The Economic Impacts of Mountaineer-

ing on One Portal Community. Tourism Analysis 1(1):5963.

Fainstein, S. S., and D. R. Judd

1999 Global Forces, Local Strategies and Urban Tourism. In The Tourist City,

D. R. Judd and S. S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 117. New Haven CT: Yale Univer-

sity Press.

Fleming, D. K., and Y. Hayuth

1994 Spatial Characteristics of Transportation Hubs: Centrality and Interme-

diacy. Journal of Transport Geography 2:318.

Getz, D.

1993 Planning for Tourism Business Districts. Annals of Tourism Research

20:583600.

Gilbert, D., and M. Clark

1997 An Exploratory Examination of Urban Tourism Impact, with Reference

to Residents Attitudes in the Cities of Canterbury and Guildford. Cities

14(6):343352.

Gladstone, D. L.

1998 Tourism Urbanization in the United States. Urban Affairs Review 34:3

27.

Gutierrez-Ronco, S.

1977 Localizacion Actual de la Hosteleria Madrilena. Boletin de la Real Socie-

dad Geograca 2:347357.

Hartmann, R.

1988 Combining Field Methods in Tourism Research. Annals of Tourism

Research 15:88105.

Hoffmann, L. M., and J. Musil

1999 Culture Meets Commerce: Tourism in Postcommunist Prague. In The

Tourist City, D. R. Judd and S. S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 179197. New Haven

CT: Yale University Press.

Jansen-Verbeke, M. C.

1986 Contribution a` lAnalyse de la Fonction Touristique des Villes Moyennes

aux Pays-Bas. Hommes et Terres du Nord 1:2130.

Jansen-Verbeke, M. C., and G. Ashworth

1990 Environmental Integration of Recreation and Tourism. Annals of Tour-

ism Research 17:618622.

Jansen-Verbeke, M. C., and E. Lievois

1999 Analysing Heritage Resources for Urban Tourism in European cities. In

Contemporary Issues in Tourism Development, D. G. Pearce and R. W. Butler,

eds., pp. 81107. London: Routledge.

Jansen-Verbeke, M. C., and E. van de Wiel

1995 Tourism Planning in Urban Revitalization Projects: Lessons from the

Amsterdam Waterfront Development. In Tourism and Spatial Transform-

ations, G. J. Ashworth and A. G. J. Dietvorst, eds., pp. 129145. Wallingford:

CAB International.

Judd, D. R.

1993 Promoting Tourism in US Cities. Tourism Management 16:175187.

1999 Constructing the Tourist Bubble. In The Tourist City, D. R. Judd and S.

S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 3553. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Judd, D. R., and S. S. Fainstein, eds.

1999 The Tourist City New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Karski, A.

1990 Urban Tourism: A Key to Urban Regeneration. The Planner (April

6):1517.

944 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

Law, C. M., ed.

1996 Tourism in Major Cities. London: Thompson International Business

Press.

Lew, A. A.

1989 Authenticity and Sense of Place in the Tourism Development Experience

of Older Retail Districts. Journal of Travel Research 27(4):1522.

Liu, J. C.

1983 Hotel Industry Performance and Planning at the Regional Level. In Tour-

ism in Canada: Selected Issues and Options, P. E. Murphy, ed., pp. 211233.

Victoria: University of Victoria.

Lopez Palomeque, F.

1995 La Estrategia del Turismo Metropolitano: El Caso de Barcelona. Estudios

Tur sticos 126:119141.

Low, L., and M. H. Toh

1997 Singapore: Development of Gateway Tourism. In Tourism and Economic

Development in Asia and Australasia, F. M. Go and C. L. Jenkins, eds., pp.

237254. London: Cassel.

March, R.

1997 An Exploratory Study of BuyerSupplier Relationships in International

Tourism: The Case of Japanese Wholesalers and Australian Suppliers. Journal

of Travel and Tourism Marketing 6(1):5568.

Marchena Gomez, M.

1995 El Turismo Metropolitano: Una Aproximacion Conceptual. Estudios

Tur sticos 126:721.

Marks, R.

1996 Conservation and Community: The Contradictions and Ambiguities

of Tourism in the Stone Town of Zanzibar. Habitat International

20:265278.

Mazanec, J.

1995 Competition Among European Cities: A Comparative Analysis with Multi-

dimensional Scaling and Self-organizing Maps. Tourism Economics 1:283

302.

Murphy, P. E.

1992a Urban Tourism and Visitor Behaviour. American Behavioral Scientist

36(2):200211.

1992b Data Gathering for Community-oriented Tourism Planning: Case Study

of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Leisure Studies 11:6579.

Obiol Menero, E. M.

1997 Turismo y Ciudad: El Caso de Valencia. Estudios Tur sticos 134:321.

OKelly, M. E.

1998 A Geographers Analysis of Hub-and-Spoke Networks. Journal of Trans-

port Geography 6(3):171186.

OKelly, M. E., and H. J. Miller

1994 The Hub Network Design Problem: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of

Transport Geography 2:3140.

ONeill, J. W.

1998 Effective Municipal Tourism and Convention Operations and Marketing

Strategies: the Cases of Boston, San Antonio and San Francisco. Journal of

Travel and Tourism Marketing 7(3):95125.

Oppermann, M.

1992 Intranational Tourist Flows in Malaysia. Annals of Tourism Research

20:482500.

Oppermann, M., K. Din, and S. Z. Amri

1996 Urban Hotel Location and Evolution in a Developing Country: The Case

of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Tourism Recreation Research 21(1):5563.

Pacquet, G.

1993 Capital Cities as Symbolic Resources. In Capital Cities: International Per-

spectives, J. Taylor, J. G. Lengelle and C. Andrew, eds., pp. 271285. Ottawa:

Carleton University Press.

Page, S.

1995 Urban Tourism. London: Routledge.

945 DOUGLAS PEARCE

Parlett, G., J. Fletcher, and C. Cooper

1995 The Impact of Tourism on the Old Town of Edinburgh. Tourism Man-

agement 16:355360.

Pearce, D. G.

1981 LEspace Touristique de la Grande Ville: E

lements de Synthe`se et Appli-

cation a` Christchurch (Nouvelle-Zelande). LEspace Geographique 10:207

213.

1984 Planning for Tourism in Belize. Geographical Review 74:291303.

1992 Tourist Organizations. Harlow: Longman.

1995 Tourism Today: A Geographical Analysis (2nd ed.). Harlow: Longman.

1996a Analysing the Demand for Urban Tourism: Issues and Examples from

Paris. Tourism Analysis 1(1):518.

1996b Tourist Organizations in Sweden. Tourism Management 17:413424.

1998a Tourist Districts in Paris: Structure and Functions. Tourism Manage-

ment 19:4965.

1998b Tourism Development in Paris: Public Intervention. Annals of Tourism

Research 25:457476.

1999 Tourism in Paris: Studies at the Microscale. Annals of Tourism Research

26:7797.

Pearce, D. G., and J. M. C. Elliott

1983 The Trip Index. Journal of Travel Research 22(1):3750.

Priestley, G. K.

1996 City Tourism in Spain. In Tourism in Major Cities, C. M. Law, ed., pp.

114154. London: Thompson International Business Press.

Renucci, J.

1992 Apercus sur le Tourisme Culturel Urbain en Region Rhone-Alpes: lEx-

emple de Lyon et de Vienne. Revue de Geographie de Lyon 67(1):518.

Roche, M.

1992 Mega-events and Micro-modernization: on the Sociology of the New

Urban Tourism. British Journal of Sociology 43:563600.

Sassen, S., and F. Roost

1999 The City: Strategic Site for the Global Entertainment Industry. In The

Tourist City, D. R. Judd and S. S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 143154. New Haven

CT: Yale University Press.

Schachar, A., and N. Shoval

1999 Tourism in Jerusalem: A Place to Pray. In The Tourist City, D. R. Judd

and S. S. Fainstein, eds., pp. 198211. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Smith, D. A., and M. Timberlake

1995 Conceptualising and Mapping the Structure of the World Systems City

System. Urban Studies 32:287302.

Stanseld, C. A.

1964 A Note on the UrbanNonurban Imbalance in American Recreational

Research. Tourist Review 19(4):196200.

Stanseld, C. A., and J. E. Rickert

1970 The Recreational Business District. Journal of Leisure Research 2:213

225.

Teo, P., and S. Huang

1995 Tourism and Heritage Conservation in Singapore. Annals of Tourism

Research 22:589615.

Timothy, D. J., and G. Wall

1995 Tourist Accommodation in an Asian Historic City. Journal of Tourism

Studies 6(1):6373.

Thorns, D. C.

1997 The Global Meets the Local: Tourism and the Representation of the New

Zealand City. Urban Affairs Review 33:189208.

van den Berg, L., J. van der Borg and J. van der Meer, eds.

1995 Urban Tourism: Performance and Strategies in Eight European Cities

Avebury: Aldershot.

van der Borg, J.

1998 La Gestion du Tourisme dans les Villes Historiques. In Le Tourisme et

946 URBAN TOURISM RESEARCH

la Ville: Experiences Europeenes, G. Cazes and F. Potier, eds., pp. 99109.

Paris: LHarmattan.

Vetter, F.

1974 On the Structure and Dynamics of Tourism in Berlin West and East. In

Studies in the Geography of Tourism, J. Matznetter, ed., pp. 237258. Frank-

furt am Main: Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universitat.

Yeoh, B. S. A., and S. Huang

1996 The Conservation-redevelopment Dilemma in Singapore: The Case of

the Kampong Glam Historic District. Cities 13:411422.

Yuan, M. S., and N. A. Christensen

1994 Wildland-inuenced Economic Impacts of Nonresident Travel on Portal

Communities: The Case of Missoula, Montana. Journal of Travel Research

32(4):2631.

Zurick, D. N.

1992 Adventure Travel and Sustainable Tourism in the Peripheral Economy

of Nepal. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 82:608628.

Submitted 1 November 1999. Resubmitted 6 June 2000. Accepted 1 August 2000. Refereed

anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Lisle S. Mitchell

También podría gustarte

- J MissaouiDocumento18 páginasJ MissaouiDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Despues Ho CartDocumento24 páginasDespues Ho CartDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- An Trop OlogiesDocumento8 páginasAn Trop OlogiesDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- J MissaouiDocumento18 páginasJ MissaouiDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- AmselleDocumento9 páginasAmselleDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- JuridicaDocumento21 páginasJuridicaDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Nambikwara 1948Documento139 páginasNambikwara 1948David Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Lhom 200 0227Documento56 páginasLhom 200 0227David Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Levi Strauss Gur VichDocumento33 páginasLevi Strauss Gur VichDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Despues Ho CartDocumento24 páginasDespues Ho CartDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Levi Strauss Gur VichDocumento33 páginasLevi Strauss Gur VichDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Journal Des AnthropologuesDocumento2 páginasJournal Des AnthropologuesDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Decert EauDocumento36 páginasDecert EauDavid Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Amsellemas 1Documento9 páginasAmsellemas 1David Lagunas AriasAún no hay calificaciones

- Extrait Logistique Et Transport International de MaDocumento20 páginasExtrait Logistique Et Transport International de MaHanane Aziz67% (3)

- Organigramme CDRDocumento1 páginaOrganigramme CDRSamen LempireAún no hay calificaciones

- BanqueDocumento142 páginasBanqueJallal Diane100% (1)

- Sociologie Des OrganisationsDocumento70 páginasSociologie Des OrganisationsSophie80% (5)

- RatingDocumento27 páginasRatingAbdelkader BoudrigaAún no hay calificaciones

- Indice Icc T2-2023Documento7 páginasIndice Icc T2-2023ousmane fayeAún no hay calificaciones

- Canevas de Budget Secteur Privé Et Société CivileDocumento6 páginasCanevas de Budget Secteur Privé Et Société CivileMoulaye TRAOREAún no hay calificaciones

- Rapport de StageDocumento7 páginasRapport de StagechaimaeAún no hay calificaciones

- Economie Industrielle (Récupération Automatique)Documento7 páginasEconomie Industrielle (Récupération Automatique)Zakaria El-AtiaAún no hay calificaciones

- 03 4 073-En-12271Documento35 páginas03 4 073-En-12271yassineAún no hay calificaciones

- De Herstatt À Lehman Brothers - Trois Accords de Bâle Et 35 Ans de Régulation BancaireDocumento4 páginasDe Herstatt À Lehman Brothers - Trois Accords de Bâle Et 35 Ans de Régulation BancaireEl MehdiAún no hay calificaciones

- L Atelier de L EclairDocumento6 páginasL Atelier de L EclairsolcelmaxAún no hay calificaciones

- CV DenisDocumento2 páginasCV DenisDenis BascopAún no hay calificaciones

- AflamDocumento3 páginasAflamYassine BoughaidiAún no hay calificaciones

- Grille Acoss 2013Documento6 páginasGrille Acoss 2013mic-grAún no hay calificaciones

- ISEEco 1998Documento14 páginasISEEco 1998Dedjima MamamAún no hay calificaciones

- Audit de Performance Renault - pdf950716717 PDFDocumento21 páginasAudit de Performance Renault - pdf950716717 PDFWalid FaridAún no hay calificaciones

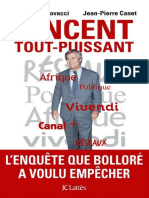

- Vincent BOLLORE Tout PuissantDocumento284 páginasVincent BOLLORE Tout Puissantyveseone0% (1)

- Theme: Brainstorming / Co-Branding / Rebranding: Année UniversitaireDocumento8 páginasTheme: Brainstorming / Co-Branding / Rebranding: Année UniversitairedsiscnAún no hay calificaciones

- Note de Lecture La Nouvelle Raison Du MondeDocumento5 páginasNote de Lecture La Nouvelle Raison Du MondeToukanphAún no hay calificaciones

- Cours MACROECONOMIEDocumento60 páginasCours MACROECONOMIEBen TanfousAún no hay calificaciones

- M&ADocumento12 páginasM&AManuel YounesAún no hay calificaciones

- Maroc Sociétés de Montage AIt Bou Guemez Rapport ISIIMMDocumento97 páginasMaroc Sociétés de Montage AIt Bou Guemez Rapport ISIIMMcheylan100% (1)

- TD CASSIS CorrectionDocumento12 páginasTD CASSIS CorrectionMohamedMohamedAún no hay calificaciones

- Pr. Benjamaa Sonia TD Macro 4 2020Documento4 páginasPr. Benjamaa Sonia TD Macro 4 2020Abdelali TouahriAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 PB PDFDocumento219 páginas1 PB PDFSoukaina IdlhajaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Référentiel d' Évaluation Vitesse - Relais 3 X 60Documento5 páginasRéférentiel d' Évaluation Vitesse - Relais 3 X 60samboss1904Aún no hay calificaciones

- ECO3 Dossier3 ÉlèveDocumento3 páginasECO3 Dossier3 ÉlèveAntoine Van SpeybroeckAún no hay calificaciones

- Dechets en PicardieDocumento224 páginasDechets en PicardieLMCUASAún no hay calificaciones