Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Kuchuk, F. J. - Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal Wells PDF

Cargado por

Nicolás Vincenti WadsworthTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Kuchuk, F. J. - Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal Wells PDF

Cargado por

Nicolás Vincenti WadsworthCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

T

Distinguished

Author Series

Well Testing and Interpretation

for Horizontal Wells

Fikri J. Kuchuk, SPE, Schlumberger Technical Services Inc.

Summary

The use of transient well testing for determining reservoir parameters

and productivity of horizontal wells has become common because of

the upsurge in horizontal drilling. Initially, horizontal well tests were

analyzed with the conventional techniques designed for vertical

wells. During the last decade, analytic solutions have been presented

for the pressure behavior of horizontal wells. New flow regimes have

been identified, and simple equations and flow regime existence cri-

teria have been presented for them. The flow regimes are now used

frequently to estimate horizontal and vertical permeabilities of the

reservoir, wellbore skin, and reservoir pressure.

Although the existing tools and interpretation techniques may be

sufficient for simple systems, innovation and improvement of the

present technology are still essential for well testing of horizontal

wells in many reservoirs with different geological environments

and different well-completion requirements.

Introduction

This paper reviews testing and interpretation methods for hori-

zontal wells. Since Renney's! article in 1941, many articles dealing

with reservoir engineering, PI, and well-testing aspects of horizon-

tal wells have appeared in the literature. 1-12 In the last decade, many

papers have been published on the pressure behavior of horizontal

wells in single-layer, homogeneous reservoirs.Jr-" Recently,

numerous papers on interpretation of horizontal well test data

21

-

26

and on the behavior of horizontal wells in naturally fractured

27

-

29

and layered

30

31

reservoirs have appeared.

Because of the uncertainty of regulating flow rate or keeping it

constant for drawdown tests in general and buildup tests (particularly

at early-times), the use of production logging tools to measure down-

hole flow rate during pressure well tests has increased in the last

decade. These tools have increased the scope of pressure-transient

well testing by providing new measurements. Drawdown tests, for

which it has often been difficult to keep the flow rate constant, can

now provide the same quality of information as buildup tests. Thus,

the possibility of obtaining reliable information about the well/reser-

voir system by using characteristic features of both transient tests

(drawdown and buildup) has increased considerably. This is particu-

larly crucial for horizontal wells, where the early-time transient data

are the most sensitive to the vertical permeability and skin if the well-

bore storage effect is minimized. Recently, production logging and

Copyright 1995 Society of Petroleum Engineers

This paper is SPE 25232. Distinguished Author Series articles are general, descriptive pa-

pers that summarize the state of the art in an area of technology by describing recent develop-

ments for readers who are not specialists in the topics discussed. Written by individuals rec-

ognized as experts in the area, these articles provide key references to more definitive work

and present specific details only to illustrate the technology. Purpose: to inform the general

readership of recent advances in various areas of petroleum engineering. A softbound

anthology, SPE Distinguished Author Series: Dec. t98t-Dec. 1983. is available from SPE's

Book Order Dept.

36

downhole shut-in have been combined'? to acquire reliable pressure/

rate data during drawdown and buildup tests.

Nonaxisymmetric drilling-fluid invasion and the long, snakelike

completed wellbore make the cleanup process difficult, particularly

toward the tips of horizontal wells. Therefore, it is important to

obtain flow profiles and the effective well length, which is often

much less than the drilled length, for the interpretation of horizontal

well tests. The effective well length is important for determining

damage skin and the vertical permeability. Production logging for

horizontal wells is now usually conducted with a coiled-tubing sys-

tem.

32

The fluid profiles also provide information about standing

water and wellbore crossflow, both common phenomena.V Unfor-

tunately, the wellbore crossflow during buildup tests makes inter-

pretation difficult. In many instances, the pressure data may not

reveal any information about the wellbore cross flow. The wellbore

temperature profiles are often useful tools for determining wellbore

crossflow for buildup tests.

Significant progress has been made over the last decade in devel-

oping forward analytical models and interpretation techniques for

horizontal wells. Many flow regimes predicted by the theory, which

are essential for system identification, have been observed in the

field examples. However, testing horizontal wells is sill challenging

in terms of measurements and interpretation. The field experience

documented in the last decade indicates that interpreting tests from

horizontal wells is much more difficult than for vertical wells.

The objective of this paper to present solutions and to describe

problems in pressure-transient testing and interpretation for hori-

zontal wells rather than to provide a scholarly review of the litera-

ture on the subject.

Flow Regimes for Horizontal Wells

Let us consider a horizontal well (Fig. I) completed in an anisotrop-

ic reservoir, which is infinite in the x and y directions. The formation

permeabilities in the principal directions are denoted by k

x

=k

y

=kH

and kz = kv, with a thickness, h, porosity, fjJ, compressibility, Ct, and

viscosity,,u. The well half-length is 4. the radius is r

w

, and the dis-

tance from the wellbore to the bottom boundary is z.,.. The boundary

conditions at the top and bottom(in the z direction) of the system are

either no flow and/or constant pressure. For this horizontal well in

a single-layer reservoir, we provide simple equations for obtaining

permeabilities and skins. There are usually several flow regimes

with different durations because of the partially penetrated nature of

horizontal wells and multiple boundary effects. For instance, as Fig.

2 shows, we may observe three radial (pseudoradial) flow regimes

for a horizontal well in a vertically bounded single-layer reservoir.

The flow regimes for horizontal wells have been investigated by

many authors,I4-18 and specific methods have been proposed to

identify flow regimes and their durations under ideal conditions.

January 1995 JPT

derivatives

Ex. 2

. _

10-4

0.1

10

pressure

Zw

x

ky

L

o

Fig. 1-Horizontal well model.

I

I

I Z

.....

H-Lw

I

I

I

""""""

h

and the damage skin as

mIl = 162.6qll/2 jkHkvL

w

(1)

s 1.151[ + 3.2275 + 2 log 1'(

. . .. .. . . . .. . . .. .. (2)

(AA)]

+ 4 - + - log --- ,

k

H

TABLE 1-RESERVOIR PARAMETERS FOR

EXAMPLES SHOWN IN FIG. 3.

h

kH kv i;

Zw

Example

.Q!L

(md) (md)

J!!L J!!L

.

1 100 100 10 500 20 0.00146

2 100 100 1 500 20 0.00389

3 100 100 5 500 5 0.00194

4 40 100 5 500 20 0.00197

5 200 200 1 500 20 0.00530

Where fwD = (f

W

/ 2L

w

l(1+

k - Il

c,

[2 (h )2]

v - 0.00026377Ct

sjb e

max zw. - z., . (4)

where lsfbe is the time to feel the second (farthest) boundary effect.

In practice. Eqs. 3 and 4 may not be reliable because the Ilcr prod-

uct may not be accurately known . Nevertheless, they can be used

qualitatively. Alternatively. because Eqs. 3 and 4 provide two pieces

of information. they may also be used to provide constraints on the

positions of the boundaries. Thi s information is useful when the

where tsnbe is the time to feel the effect of the nearest boundary. or

where q is the constant flow rate, !i.PI hr = Po- Pw(t= I hour) for

drawdown tests, and !i.Plhr=Pw(!i.t=1 hour) - (!i.t- 0) for buildup

tests. Pw at 1hour for both tests is obtained from the semilog, Horner,

or derivative plot.

In principle, the geometric mean permeability j kHk

v

and damage

skin may be obtained from the first radial flow regime. provided thaI

the wellbore pressure during this regime is not affected by wellbore

storage and/or boundaries. The anisotropy ratio is needed for calcu-

lati7 damage skin from Eq. 2. However, because the dependence

on kH/k

v

is logarithmic. its effect on the damage skin estimation

will usually be small.

The vertical permeability may be obtained from the time of onset

of the deviation of the pressure or pressure deri vative from this flow

regime as (in oilfield units)

k - Il

c,

. 2 2

V - 00002637 t mm [zw.(h - zw)], (3)

. "I. snbe

Fig. 3-Derivatives for Examples 1 through Sand pressure for

ExampleS.

10-

2

Third radi al

_J ._.

Time

Fig. 2-Radial flow regimes for a horizontal well.

First radial

7

-

r

Hemi-radial

-.. ..r--.

First Radial Flow Regime. The first flow pattern for horizontal

wells is ellipti c-cylindrical. After some time. the elliptic-cylindrical

flow regime becomes pseudoradial, as shown in Fig. 2. This radial

flow around the wellbore may continue until the effect of the nearest

boundary is felt at the wellbore. It may not develop if the anisotropy

ratio. kH/kV. is large. The behavior of this regime is similar to the ear-

ly-time behavior of partially penetrated wells. The derivatives for

all examples, for which the well/reservoir parameters are given in

Table 1 (see Ref. 18), clearly indicate (Fig. 3) the first radial flow

regime . The slope of the semilog straight line can be expressed as

Log-log plots the change in the wellbore pressure. !i.p...

associated with type curves have been used extensively as diagnostic

and interpretation tools since the early 1970's.9 In the early 1980s.

Bourdet et al.

33

showed that a combined log-log plot of pressure and

pressure derivative is a better diagnostic and interpretation tool than

a pressure plot alone for comparing measured transient data with the

model responses. In this paper. the pressure change and pressure

derivative are denoted by !i.Pw and dPw/dIn t. respectively.

10

OJ

.2:

Cii

>

o

JPI' January 1995 37

location of one of the boundaries changes with time, such as when

the gas cap moves downward or when there is an unknown continu-

ous shale above or below the well.

Second Radial Flow Regime. This is a hemicylindrical flow

regime, as shown in Fig. 2, that follows the first radial flow. This

flow regime may occur when the well is not centered with respect

to the no-flow top and bottom boundaries. In some cases, only this

flow regime may be observed without the first flow regime. The

slope obtained from this flow regime is two times larger than that

obtained from the first regime. Thus,

mrz = 2m

rl

(5)

and

s 2302{ + 32275 + IO{(1 + fj;) ;:]

- log ( ,/,kHkVz) } . . (6)

-r/lctrw

As in the first radial flow regime, the geometric mean permeability

j kH/k

v

and damage skin may be obtained from this flow regime.

Intermediate-Time Linear Flow Regime. If the horizontal well is

much longer than the formation thickness, this flow regime may

develop after the effects of the upper and lower boundaries are felt

at the wellbore. As Fig. 3 shows, the derivative for Example 4 exhib-

its a linear flow regime for almost one logarithmic cycle because the

formation thickness (Table I) is short (40 ft). The slope of the linear

straight line (plot of pressure vs. the square root of time) is given by

mil = (8.128q/2L

wh)j/l/kJIPc,

(7)

and the skin by

S = (2LwjkHk v/141.2q/l)!1POhr

+ 2.303

where !1POhr is the intercept. Note that if bo. jkv/k

H

(h/L

w),

is not

small, then the linear flow regime will not take place because the

flow will spread out significantly from the ends of the well before

the effects of the top and bottom boundaries are seen.

Third (Intermediate) Radial FlowRegime. After the effects of the

top and bottom boundaries are felt at the wellbore, a third radial flow

pattern will develop (Fig. 2) in the x-y plane. This regime does not

exist for wells with a gas cap or aquifer. The semilog straight-line

slope is

m

r

3 = 162.6q/l/k

Hh

(9)

and the skin is

(10)

where S, - 2303 IO{ (1 + jf;}-

- fj; L(t - + (11)

38

Eq. 11 is valid only for no< 2.5. The full expression given by

Kuchuk et ai.

18

should be used when ro 2.5.

The start of this flow regime can be written as18

tv = 20, (12)

where tv = (13)

The start ofthe third radial flow regime defined by Eq. 12is some-

what subjective. Clonts and Ramey,13 Goode and Thambynaya-

gam.!" Ozkan et ai.,16 and Odeh and Babu17 presented different

expressions for the start of the third regime. Although it can be used

only qualitatively to determine an upper bound to the horizontal

permeability (see Fig. 3), Eq. 12 is a good approximation for the

start of the third radial flow regime. However, for bo 1, Eq. 12

becomes crude, as shown by Curves 2 and 5 in Fig. 3. For these two

examples, the start times are actually less than those obtained from

Eq. 12. For large anisotropy ratios, ho may become large, and the

start of the radial flow regime could be much larger than that

obtained from Eq. 12.

Other flow regimes may also develop, depending on the outer

boundaries in the x and y directions and the well geometry. For

example, a spherical flow regime may occur if a horizontal well is

much shorter than the formation thickness.

Constant-Pressure Boundary. If the top or bottom boundary is at

a constant pressure, a steady-state pressure is achieved at the well-

bore. The total skin can then be expressed as

s = (jkHk

v

Lw/374.4q/l)!1Pss - 2.303

I

[

8h (nz

w)

(h - zw) fj;H]

X og ( 2h + --r::- k

v

'

nr; 1 + ,;kv/k

H

...................... (14)

where !1pss is the pressure difference between the well pressure and

constant pressure at the boundary. The height of the formation may

be estimated from the time lcbp- at which the wellbore pressure

becomes steady state, as

h = 0.01 jkvtCbP/cjJ/lCt, (15)

where tcbp is the time to reach the steady-state pressure at the well-

bore. Alternatively, if h is known, this equation may be used to esti-

mate the vertical permeability.

Interpretation

Horizontal test well data may be interpreted in two steps: the first is

the identification of the boundaries and the main features, such as

faults and fractures, of the model from flow regime analyses. Unlike

most vertical wells, well test measurements from horizontal wells

are usually affected by nearby shale strikes and lenses and by top

and bottom boundaries at early times. The second step is to estimate

well/reservoir parameters and to refine the model that is obtained

from flow regime analyses.

The graphical type curve procedure is practically impossible for

the analysis of horizontal well test data because usually more than

three parameters are unknown, even for a single-layer reservoir.

Thus, along with the flow regime analyses, nonlinear least-squares

techniques are usually used to estimate reservoir parameters. In

applying these methods, one seeks not merely a model that fits a

given set of output data (pressure, flow rate, and/or their derivatives)

but also knowledge of what features in that model are satisfied by

the data. Evaluation of model features can be done iteratively during

estimation and by the diagnostic tools mentioned above (identifying

flow regimes). However, if the uncertainties about the model can be

resolved with the diagnostic tools, the estimation can be carried out

with a greater confidence at a minimal cost. For instance, if the loca-

tions of the lower and upper boundaries are known or identified

January 1995 JPT

Fig. 5-The permeability and thickness distributions for the

nine-layer reservoir.

Layered Reservoirs. Most oil and gas reservoirs are often layered

(stratified) to various degrees because of sedimentation processes

over long geologic times. The geologic characterization of layered

reservoirs and their evaluation have received increasing attention in

recent years because of the widespread use of 3D seismic and high-

resolution wireline logs.

Understanding the pressure-transient behavior of layered reser -

voirs is important because of the strong influence that layering has

on the productivity of horizontal weIIs.

12

However, single-layer

models are often used for the interpretation of weII-test data from

layered reservoirs. Recently, an interesting example-" was pres-

ented to examine the behavior of a horizontal weII in a nine-layer

reservoir and in two equivalent single-layer reservoirs. The nine-

layer system consists of nine different-thickness horizontal layers

with high and low horizontal and vertical penneabilities randomly

distributed among the layers (Fig. 5) . In this nine-layer reservoir,

each layer is a laterally and vertically continuous flow unit that com-

municates vertically (formation crossflow) with adjacent layers

in the z direction. The horizontal well is completed in the middle

of the fifth layer. For computation of the single-layer response,

we used the thickness-weighted arithmetic average horizontal

permeability < k

H

> = [k7= j(kH);h;]/h, and the harmonic aver-

age vertical nneability < k

v

> = hr7k7=lhj(kvl; or < k

v

> =

k7=1 (kHkv);hjh

r

(the < kHk

v

> curve in Fig. 6), where lit =

k7=A

As shown in Fig. 6, the derivatives for these three cases clearly

indicate the first radial flow regime before the effects of the bottom

100

kH

!iJ kv

80 60 40

permeability, md

20 a

5

g) 15 '.:.::::\,:x";-,:x

20

:

10

15.

Fractured Reservoirs. Many horizontal weIIs have been drilled in

fractured reservoirs, such as Respo Mare" and Austin Chalk,23 to

increase production. The solutions presented for horizontal wells in

naturaIIy fractured (double-porosity) reservoirs are a simple exten-

sion of homogeneous single-layer solutions.

27-29

Although the

double-porosity model may work for late-time behavior, it does not

work at early- and middle-time intervals unless the fracture density

is very high and its conductivity is low.

1000

from the flow regime analyses, the horizontal and vertical pennea-

Lilities and damage skin can beestimated with a greater confidence.

The well bore volume of horizontal wells is usually larger than

those of vertical wells. Field observations indicate that well bore

storage may vary considerably as pressure builds up. The effect of

wellbore storage can be easily eliminated or reduced if the down-

hole flow rate is measured and analyzed with the bottornhole pres-

sure. As stated, a downhole shut-in tool should be used for buildup

tests, particularly for low-productivity wells, to minimize the weII-

bore storage effect.

It is well known that the estimated parameters for horizontal wells

are strongly correlated. For instance, vertical permeability and well-

bore storage are strongly correlated. Skin is correlated to both kH

and ky. As recommended by Kuchuk et al.,21 it may be necessary to

conduct a short drawdown test and a long buildup test for flowing

wells to estimate these parameters confidently. These two tests

should be carried out sequentially. For shut-in weIIs, the drawdown

should be long enough to minimize the effect of producing time.

Fig, 4 presents pressure derivatives for two drawdown and two

72-hour buildup tests with a 24-hour producing time for the same

system with different vertical penneabilities. For the drawdown

tests, derivatives are taken with respect to the logarithmic of the test

time. For buildup tests, derivatives are taken with respect to the log-

arithm of the Homer time (t

p

+6. t}/6.t, where t

p

is the producing

time and 6.t is the test time].

As Fig. 4 shows, even for a 24-hour producing time, the effect is

visible. The behavior of the low-vertical-permeability case is not

drastically different from that of the high-vertical-permeability

case. A 24-hour producing time is about the minimum time required

to flow the well for these two systems. The drawdown derivative

type curves without skin and storage for these two systems are pres-

ented in Fig. 3 as Example 1 (ky =10 md) and Example 2 (ky =I

md). Note that none of the flow regimes that are clearly visible in

Fig. 3 can be identified in Fig. 4 because of the weIIbore storage and

skin effects. Although these are noise-free synthetic data, the third

radial flow regime is hardly identifiable even at 72 hours. This prob-

lem would become much more pronounced for real tests . If the

downhole flow rate is measured or a downhole shut-in device is

used, the identifiable data interval would then be increased.

--nine-layer

harmonic <ky>

-----harmonic <kHky>

'R

gj'

... 100

QJ

"0

--DOfor kv=10md

11 BUfor kv=lO md

---.- DD for kv = 1 md

o BUfor ky= 1 md 100

10

time, hr

Fig. 4-Comparison of derivatives for drawdowns and buildUps

for different vertical permeabllities.

Fig. 6-Comparison of derivatives for layered and equivalent

homogeneous single-layer systems.

JPT January 1995 39

and top no-flow boundaries. After a transition period, all curves flat-

ten, indicating a late-time radial flow regime. This occurs because

during this period the horizontal well behaves as a point-source well

in the x-y plane. As Fig. 6 shows, the behavior of the nine-layer res-

ervoir is completely different from that for a reservoir with two

equivalent single layers, except for the late-time radial flow regime,

which evolves in 100 hours. Note that the shape of the derivative of

the nine-layer case is similar to that of the single-layer case given

by Example I (Fig. 3). Consequently, identification of such a layer

system may not be possible and may also lead to an incorrect inter-

pretation, particularly in estimating the vertical permeability and the

distance to the boundaries. As Fig. 6 also shows, it is difficult to say

which averaging techniques work better for vertical permeability.

Therefore, a multilayer reservoir generally cannot be treated as an

equivalent single-layer system, except when the permeability varia-

tions are small .

30

.

In addition, the behavior of the gas and water zones may differ

from that of the constant-pressure boundary condition, and the

effect of a gas cap or a water zone should not automatically be

assumed as a constant-pressure boundary.P

Conclusions

Over the last decade, significant progress has been made in develop-

ing forward analytical models and interpretation techniques for hor-

izontal wells. The effects of the top and the bottom boundaries, such

as no-flow and/or constant-pressure boundaries, on the transient

behavior of horizontal wells have been recognized. Flow regimes

have been presented for system identification and for estimation of

a number of reservoir parameters.

A wide variety of testing equipment (hardware) for vertical wells

has been adapted for testing horizontal wells. Production logging

and/or downhole shut-in have been used successfully to acquire reli-

able pressure and rate data for drawdown and buildup tests. Produc-

tion logging tools usually have been run with a coiled-tubing system.

Field experience indicates that the interpretation of well tests

from horizontal wells is much more difficult than for vertical wells .

A large anisotropy ratio and the existence of multiple boundaries

with unknown distances to the wellbore increase the complexity of

the interpretation. Minimizing the well bore storage effect is crucial

for system identification and parameter estimation.

The pressure derivative is shown to be an effective system identi-

fication tool that can also provide initial approximations of the non-

linear estimation. Relying solely on nonlinear estimation without

diagnostics may lead to an erroneous model and estimates.

The behavior of a multilayer reservoir with a horizontal well can-

not be treated as an equivalent single-layer system with average

properties.

Nomenclature

c/ = total compressibility, Lt

2tm

, psi - I

h = thickness, L, ft

k= permeability, L2, md

L = length, L, ft

m= slope

n = number of layers

p= pressure, mlLt

2,

psi

q = flow rate, L

3tt,

RB/D

r = radius, L, ft

S= skin

t = time, t, hours

x, y, z= coordinates, L, ft

Jl = viscosity, mILt, cp

ljJ = porosity, fraction

Subscripts

D = dimensionless

H = horizontal

hr= hour

i = layer number

1= linear

0= initial or original

40

p = producing

r= radial

ss = steady-state

t= total

v= vertical

w= well

wf= flowing pressure (drawdown)

x, y,z= coordinate indicator

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Schlumberger for permission to publish this paper.

I am indebted to P.A. Goode, R.M. Thambynayagam, and DJ.

Wilkinson for their contributions to horizontal well testing.

References

\. Renney, L.: "Drilling Wells Horizontally," Oil Weekly (Jan. 20,1941 )

12.

2. Giger, EM., Reiss, L.H., and Jourdan, A.P.: "Reservoir Engineering

Aspects of Horizontal Drilling ," paper SPE 13024 presented at the 1984

SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, Sept.

16-19.

3. Giger, EM.: "Horizontal Wells Production Techniques in Heteroge-

neous Reservoirs," paper SPE 13710 presented at the 1985 SPE Middle

East Oil Technical Show, Bahrain, March 11-14.

4. Reiss, L.H.: "Production From Horizontal After 5 Years," 1PT (Nov.

1987) 1411; Trans. , AIME, 283.

5. Sherrard. D.W., Brice, B.W., and MacDonald , D.G.: "Application of

Horizontal Wells at Prudhoe Bay," 1PT(Nov. 1987) 1417.

6. King, G.R. and Ertekin, T.: "Comparative Evaluation of Vertical and

Horizontal Drainage Wells for the Degasification of Coal Seams,"

SPERE (May 1988) 720.

7. Babu, O.K. and Odeh, A.S.: "Productivity of a Horizontal Well,"

SPERE (Nov. 1989) 417.

8. Joshi, S.D.: "Augmentation of Well Productivity With Slanted and Hor-

izontal Wells," 1PT (June 1988) 729; Trans., AIME 285.

9. Karcher, BJ., Giger, EM., and Combe , J.: "Some Practical Formulas to

Predict Horizontal Well Behavior," paper SPE 15430 presented at the

1986 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans,

Oct . 5-8.

10. Goode, P.A. and Kuchuk, FJ.: "Inflow Performance of Horizontal

Wells," SPERE(Aug. 1991) 319.

I \. Goode, P.A. and Wilkinson, OJ.: "Inflow Performance of Partially

Open Horizontal Wells," 1PT(Aug. 1991) 983.

12. Kuchuk, FJ. and Saaedi, J: "Inflow Performance of Horizontal Wells in

Multilayer Reservoirs," paper SPE 24945 presented at the 1992 SPE

Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Washington, DC, Oct. 4-7.

13. Clonts, M.D. and Ramey, HJ. Jr.: "Pressure Transient Analysis for

Wells with Horizontal Drainholes,' paper SPE 15116 presented at the

1986 SPE California Regional Meeting, Oakland, April 2--4.

14. Goode, P.A. and Thambynayagam, R.M.: "Pressure Drawdown and

Buildup Analysis for Horizontal Wells in Anisotropic Media," SPEFE

(Dec. 1987) 683; Trans., AIME, 283.

15. Daviau, E et al .: "Pressure Analysis for Horizontal Wells," SPEFE

(Dec. 1988) 716.

16. Ozkan, E., Raghavan, R., and Joshi, S.D. : "Horizontal Well Pressure

Analysis," SPEFE (Dec. 1989) 567; Trans . AIME, 287.

17. Odeh, A.S. and Babu, O.K.: "Transient Flow Behavior of Horizont al

Wells: Pressure Drawdown and Buildup Analysis," SPEFE (March

1990) 7; Trans ., AIME, 289,

18. Kuchuk, FJ. et al .: "Pressure-Transient Behavior of Horizontal Wells

With and Without Gas Cap or Aquifer," SPEFE (March 1991) 86;

Trans ., AIME. 291.

19. Rosa, AJ and Carvalho, R.S.: "A Mathematical Model for Pressure

Evaluation in an Infinite-Conductivity Horizontal Well," SPEFE (Dec.

1989) 559.

20. Ozkan. E. and Raghavan , R.: "Performance of Horizontal Wells Subject

to Bottomwater Drive," SPERE (Aug. 1990) 375; Trans. AIME, 289,

2\. Kuchuk, FJ. et al.: "Pressure Transient Analysis for Horizontal Wells,"

JPT (August 1990) 974; Trans., AIME, 289.

22. Abbaszadeh, M. and Hegeman, P.: "Pressure-Transient Analysis for a

Slanted Well in a Reservoir With Vertical Pressure Support," SPEFE

(Sept. 1990) 277; Trans ., AIME, 289.

23. Lichtenberger, GJ.: "Pressure Buildup Test Results From Horizontal

Wells in the Pearsall Field of the Austin Chalk," paper SPE 20609 pres-

ented at the 1990 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibit ion,

New Orleans, Sept. 23-26.

January 1995 JIYI'

SI Metric Conversion Factors

Canadian SPEICIM/CANMET IntI. Conference on Recent Advances in

Horizontal Well Applications, Calgary, March 20-23.

Fikri J. Kuchuk is chief reservoir engineer for Schlumberger

Middle East in Dubai. He was a senior scientist and a group

leader at Schiumberger-Doll Research Center, Ridgefield , CT,

and conducted research in pressure transient testing , inverse

problem, flow through porous media, and downhole pressure

and flow rate measurements. He was a consulting professor in

the Petroleum Engineer ing Dept. of Stanford U. during

1988-1994. Kuchuk was the recipient of the 1994 Reservoir Engi-

neering Award. He was the Program Chairman for the 1993

Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition and has chaired

many SPEtechnical committees.

E-OI =m

E-04 =,um

2

E+OO = kPa

ft x 3.048*

md x 9.869 233

psi x 6.894 757

"Conva rsion factor is exact.

24. Rosenzweig, U., Korpics, D.C., and Crawford, G.E.: "Pressure Tran-

sient Analysis of the JX-2 Horizontal Well, Prudhoe Bay, Alaska," pa-

per SPE 20610 presented at the 1990 SPE Annual Technical Conference

and Exhibition, New Orleans, Sept. 23-26.

25. Shah, P.C., Gupta , D.K., and Deruyck, B.G.: "Field Application of the

Method for Interpretation of Horizontal-Well Transient Tests," SPEFE

(March 1994) 23.

26. Suzuki, K. and Nanba, T.: "Horizontal Well Test Analysis System," pa-

per SPE 20613 presented at the 1990SPE Annual Technical Conference

and Exhibition, New Orleans, Sept. 23-26.

27. Carvalho, R.S. and Rosa, AJ .: ' 'Transient Pressure Behavior for Hori-

zontal Wells in Naturally Fractured Reservoir," paper SPE 18302 pres-

ented at the 1988 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition,

Houston, Oct. 2- 5.

28. Williams, E.T. and Kikani, 1.: "Pressure Transient Analysis of Horizon-

tal Wells in a Naturally Fractured Reservoir," paper SPE 20612 pres-

ented at the 1990 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition,

New Orleans, Sept. 23- 26.

29. Aguilera, R. and Ng, M.e.: "Transient Pressure Analysis of Horizontal

Wells in Anisotropic Naturally Fractured Reservoirs," SPEFE (March

1991) 95.

30. Kuchuk, FJ.: "Pressure Behavior of Horizontal Wells in Multilayer

Reservoirs With Crossflow,' paper SPE 22731 presented at the 1991

SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, Oct. 6-9.

31. Suzuki, K. and Namba, T.: "Horizontal Well Pressure Transient Behav-

ior in Stratified Reservoirs," paper SPE 22732 presented at the 1991

SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, Oct. 6-9.

32. Domzalski, S. and Yver, J.: "Horizontal Well Testing in the Gulf of

Guinea," Oil Field Review (Apri l 1992) 42.

33. Bourdet, D. et al.: "A New Set of Type Curves Simplifies Well Test

Analysis," World Oll (May 1983).

34. Kuchuk, FJ . and Kader, A.S: "Pressure Behavior of Horizontal Wells

in Heterogeneous Reservoirs," paper HWC94-25 presented at the 1994

JPT January 1995 41

También podría gustarte

- Pressure Transient Formation and Well Testing: Convolution, Deconvolution and Nonlinear EstimationDe EverandPressure Transient Formation and Well Testing: Convolution, Deconvolution and Nonlinear EstimationCalificación: 2 de 5 estrellas2/5 (1)

- Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal WellsDocumento6 páginasWell Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal Wellsmiguel_jose123Aún no hay calificaciones

- Well Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal WellsDocumento6 páginasWell Testing and Interpretation For Horizontal WellsGaboGagAún no hay calificaciones

- Kuchuk 1995Documento6 páginasKuchuk 1995petroleumTY wpuAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE Analysis of Slug Test Data From Hydraulically Fractured Coalbed Methane WellsDocumento14 páginasSPE Analysis of Slug Test Data From Hydraulically Fractured Coalbed Methane WellsJuan Manuel ContrerasAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 89334 Analysis of The Effects of Major Drilling Parameters On Cuttings Transport Efficiency For High-Angle Wells in Coiled Tubing Drilling OperationsDocumento8 páginasSPE 89334 Analysis of The Effects of Major Drilling Parameters On Cuttings Transport Efficiency For High-Angle Wells in Coiled Tubing Drilling OperationsmsmsoftAún no hay calificaciones

- Part 16 Horizontal Well TestingDocumento16 páginasPart 16 Horizontal Well TestingChai CwsAún no hay calificaciones

- Analyze Oil Well Pressure Buildup TestDocumento49 páginasAnalyze Oil Well Pressure Buildup Testmeilani5Aún no hay calificaciones

- Pressure Transient Analysis and Inflow Performance For Horizontal WellsDocumento16 páginasPressure Transient Analysis and Inflow Performance For Horizontal WellsednavilodAún no hay calificaciones

- Chern 2007Documento8 páginasChern 2007Albab HossainAún no hay calificaciones

- Reservoir Eng For Geos 6Documento3 páginasReservoir Eng For Geos 6StylefasAún no hay calificaciones

- Well-Test Analysis For Naturally Fractured Reservoirs: SeriesDocumento4 páginasWell-Test Analysis For Naturally Fractured Reservoirs: SeriesIván VelázquezAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 144583 A Semi-Analytic Method For History Matching Fractured Shale Gas ReservoirsDocumento14 páginasSPE 144583 A Semi-Analytic Method For History Matching Fractured Shale Gas Reservoirstomk2220Aún no hay calificaciones

- Analisa Pressure Build Up TestDocumento28 páginasAnalisa Pressure Build Up TestDerips PussungAún no hay calificaciones

- Analisa Pressure Build Up TestDocumento49 páginasAnalisa Pressure Build Up TestLuc ThirAún no hay calificaciones

- 09 Well Test Interpretation in Hydraulically Fracture WellsDocumento30 páginas09 Well Test Interpretation in Hydraulically Fracture WellstauseefaroseAún no hay calificaciones

- Fractured ReservoirsDocumento23 páginasFractured Reservoirstassili17Aún no hay calificaciones

- Well-Test Horizontal Well, Student PresentationDocumento13 páginasWell-Test Horizontal Well, Student PresentationGabriel ColmontAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 114591 Rate Transient Analysis in Naturally Fractured Shale Gas ReservoirsDocumento17 páginasSPE 114591 Rate Transient Analysis in Naturally Fractured Shale Gas ReservoirsIbrahim ElsawyAún no hay calificaciones

- Variations in Clear Water Scour Geometry at Piers of Di Erent e Ective WidthsDocumento15 páginasVariations in Clear Water Scour Geometry at Piers of Di Erent e Ective Widthsfernando salimAún no hay calificaciones

- Otc-6333 - Dedicated Finite Element Model For Analyzing Upheaval Buckling Response of Submarine PipelinesDocumento10 páginasOtc-6333 - Dedicated Finite Element Model For Analyzing Upheaval Buckling Response of Submarine PipelinesAdebanjo TomisinAún no hay calificaciones

- Draft Tube SurgesDocumento33 páginasDraft Tube SurgesvesselAún no hay calificaciones

- Butterfly Valve and FlowDocumento5 páginasButterfly Valve and FlowMurugan RangarajanAún no hay calificaciones

- IADC/SPE-178881-MS Swab and Surge Pressures With Reservoir Fluid Influx Condition During MPDDocumento13 páginasIADC/SPE-178881-MS Swab and Surge Pressures With Reservoir Fluid Influx Condition During MPDqjbsexAún no hay calificaciones

- Burley 1985 Aquacultural-EngineeringDocumento22 páginasBurley 1985 Aquacultural-EngineeringJorge RodriguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Hole Cleaning Performance of Light-Weight Drilling Fluids During Horizontal Underbalanced DrillingDocumento6 páginasHole Cleaning Performance of Light-Weight Drilling Fluids During Horizontal Underbalanced Drillingswaala4realAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 12895-1984-P.,Griffith - Multiphase Flow in Pipes PDFDocumento7 páginasSPE 12895-1984-P.,Griffith - Multiphase Flow in Pipes PDFGustavo Valle100% (1)

- CFD Ball ValveDocumento8 páginasCFD Ball ValveKelvin Octavianus DjohanAún no hay calificaciones

- Experimental Investigation of Pressure Distribution On A Rectangular Tank Due To The Liquid SloshingDocumento14 páginasExperimental Investigation of Pressure Distribution On A Rectangular Tank Due To The Liquid Sloshingtravail compteAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 77951 Multirate Test in Horizontal Wells: SurcolombianaDocumento12 páginasSPE 77951 Multirate Test in Horizontal Wells: SurcolombianaJorge RochaAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 145808 Three-Phase Unsteady-State Relative Permeability Measurements in Consolidated Cores Using Three Immisicible LiquidsDocumento12 páginasSPE 145808 Three-Phase Unsteady-State Relative Permeability Measurements in Consolidated Cores Using Three Immisicible LiquidsCristian TorresAún no hay calificaciones

- Wel Configurations in Anisotropic Reservoirs SPEDocumento6 páginasWel Configurations in Anisotropic Reservoirs SPErichisitolAún no hay calificaciones

- Multiphase FlowDocumento15 páginasMultiphase FlowvictorvikramAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 48937 Effect of Completion Geomety and Phasing On Single-Phase Horizontal Wells Liquid Flow Behavior inDocumento12 páginasSPE 48937 Effect of Completion Geomety and Phasing On Single-Phase Horizontal Wells Liquid Flow Behavior inPablo A MendizabalAún no hay calificaciones

- Flow of Water by Notch and WeirsDocumento17 páginasFlow of Water by Notch and WeirsMuhammad Zulhusni Che RazaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Wen Atid Can: Performance of Distillate Reservoirs in Gas CyclingDocumento16 páginasWen Atid Can: Performance of Distillate Reservoirs in Gas CyclingSamuel Quintero HerreraAún no hay calificaciones

- Flow Over WeirsDocumento13 páginasFlow Over WeirsAkmalhakim Zakaria100% (4)

- NACA TN 3169 RoshkoDocumento30 páginasNACA TN 3169 RoshkodickysilitongaAún no hay calificaciones

- Flow of Water by Notch and WeirsDocumento15 páginasFlow of Water by Notch and WeirsCik Tiem Ngagiman93% (29)

- PressureDrop IJFMRDocumento18 páginasPressureDrop IJFMRThinh Tran HungAún no hay calificaciones

- Well Testing Methods Reveal Reservoir PropertiesDocumento28 páginasWell Testing Methods Reveal Reservoir PropertiesDHIVAKAR AppuAún no hay calificaciones

- Test Pumping Test in Fractured ReservoirsDocumento6 páginasTest Pumping Test in Fractured ReservoirsZulu75Aún no hay calificaciones

- Analytical modelling of groundwater wells and well systemsDocumento40 páginasAnalytical modelling of groundwater wells and well systemsMagdy BakryAún no hay calificaciones

- Ojo Poe SLBDocumento16 páginasOjo Poe SLBSebastian MorenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Labyrinth WierDocumento5 páginasLabyrinth Wiershefali1501Aún no hay calificaciones

- Use of Coiled Tubing As A Velocity StringDocumento3 páginasUse of Coiled Tubing As A Velocity StringMark Johnson100% (1)

- Lab Manual (Hydraulics Engineering)Documento34 páginasLab Manual (Hydraulics Engineering)Shahid Kamran63% (8)

- B. Tech. Petroleum Engineering: University College of Engineering Kakinada (A)Documento20 páginasB. Tech. Petroleum Engineering: University College of Engineering Kakinada (A)54 Pe AravindswamyAún no hay calificaciones

- Numerical modelling of subcritical open channel flowDocumento7 páginasNumerical modelling of subcritical open channel flowchrissbansAún no hay calificaciones

- Transient Analyses of Interceptor TrenchDocumento9 páginasTransient Analyses of Interceptor TrenchAmanda CervantesAún no hay calificaciones

- Lewis F. Moody, Friction Factor For Pipe Flow, 1944Documento19 páginasLewis F. Moody, Friction Factor For Pipe Flow, 1944Lion Rock0% (1)

- Department of Mechanical and Industrial TechnologyDocumento20 páginasDepartment of Mechanical and Industrial TechnologyMPHILWENHLE JELEAún no hay calificaciones

- Modelling Sedimentation TanksDocumento45 páginasModelling Sedimentation TanksJeremy DudleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Flood Routing - 1Documento36 páginasFlood Routing - 1SAURABH GUPTAAún no hay calificaciones

- Spe 126Documento13 páginasSpe 126advantage025Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Effect of Perforating Conditions On Well PerfonnanceDocumento9 páginasThe Effect of Perforating Conditions On Well PerfonnancerafaelAún no hay calificaciones

- Pipeline Design for Water EngineersDe EverandPipeline Design for Water EngineersCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Hydraulic Tables; The Elements Of Gagings And The Friction Of Water Flowing In Pipes, Aqueducts, Sewers, Etc., As Determined By The Hazen And Williams Formula And The Flow Of Water Over The Sharp-Edged And Irregular Weirs, And The Quantity DischargedDe EverandHydraulic Tables; The Elements Of Gagings And The Friction Of Water Flowing In Pipes, Aqueducts, Sewers, Etc., As Determined By The Hazen And Williams Formula And The Flow Of Water Over The Sharp-Edged And Irregular Weirs, And The Quantity DischargedAún no hay calificaciones

- Workover Equipment GuideDocumento21 páginasWorkover Equipment GuideHaries SeptiyawanAún no hay calificaciones

- Vol 7Documento422 páginasVol 7yasaswyAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 189134 Economic Optimization of Water and Gas Shut Off Treatment in Oil WellsDocumento16 páginasSPE 189134 Economic Optimization of Water and Gas Shut Off Treatment in Oil WellsEdgar GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- 2021 Upstream CatalogDocumento76 páginas2021 Upstream CatalogChimaroke Uchechukwu AnyanwuAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 6-Well Completion UTMDocumento51 páginasChapter 6-Well Completion UTMNurzanM.Jefry50% (2)

- SPE Plunger LiftDocumento19 páginasSPE Plunger LiftEdwin VargadAún no hay calificaciones

- Basic Applied Reservoir Simulation - (1 - Introduction) PDFDocumento10 páginasBasic Applied Reservoir Simulation - (1 - Introduction) PDFix JanAún no hay calificaciones

- BP Squeeze CementingDocumento2 páginasBP Squeeze CementingilkerkozturkAún no hay calificaciones

- Exwell Lock MandrelDocumento1 páginaExwell Lock MandrelLuis David Concha CastilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Hydraulic-Fracture Design: Optimization Under Uncertainty: Risk AnalysisDocumento4 páginasHydraulic-Fracture Design: Optimization Under Uncertainty: Risk Analysisoppai.gaijinAún no hay calificaciones

- Degassing Stations and Gas-Oil Separation ProcessDocumento12 páginasDegassing Stations and Gas-Oil Separation ProcessashrafsaberAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 63088 EOS of State of A Complex Fluid in OrocualDocumento14 páginasSPE 63088 EOS of State of A Complex Fluid in OrocualWilmer CuicasAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 134586 Casing Drilling Application WDocumento17 páginasSPE 134586 Casing Drilling Application WAmine MimoAún no hay calificaciones

- Baker Bsee Iadc PDFDocumento10 páginasBaker Bsee Iadc PDFAbhinav Hazra100% (1)

- Introduction Well ControlDocumento37 páginasIntroduction Well ControlEkkarat RattanaphraAún no hay calificaciones

- Baker Multistage Annular FracturingDocumento16 páginasBaker Multistage Annular FracturingzbhdzpAún no hay calificaciones

- Further (Sat, Igcse) Mathematics Tutor.: Personal InfoDocumento6 páginasFurther (Sat, Igcse) Mathematics Tutor.: Personal InfoEngr. Douglas IdieseruAún no hay calificaciones

- Cover Lettre Master GreecDocumento1 páginaCover Lettre Master GreecMallouli KeremAún no hay calificaciones

- Oman Drilling Contractor NDSC ProfileDocumento4 páginasOman Drilling Contractor NDSC Profilecmrig74Aún no hay calificaciones

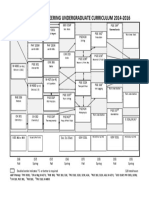

- Petroleum Engineering Undergraduate Curriculum 2014-2016Documento1 páginaPetroleum Engineering Undergraduate Curriculum 2014-2016Lopez RamAún no hay calificaciones

- Production Technology For Other Disciplines - PTODocumento4 páginasProduction Technology For Other Disciplines - PTOGama ArthurAún no hay calificaciones

- Well control worksheet drillers methodDocumento1 páginaWell control worksheet drillers methodTriana Priyo SunjoyoAún no hay calificaciones

- SPE 129177 Polymer Injection in Heavy Oil Reservoir Under Strong Bottom Water DriveDocumento15 páginasSPE 129177 Polymer Injection in Heavy Oil Reservoir Under Strong Bottom Water DriveLeopold Roj DomAún no hay calificaciones

- IADC WellCAP Well ControlDocumento3 páginasIADC WellCAP Well ControlJorge ToalaAún no hay calificaciones

- Underbalanced Drilling (UBD) : Lesson 1Documento39 páginasUnderbalanced Drilling (UBD) : Lesson 1HunterAún no hay calificaciones

- Gas Engineer's ResumeDocumento1 páginaGas Engineer's Resumeeng20072007Aún no hay calificaciones

- Workover PresentationDocumento32 páginasWorkover PresentationNicky Adriaansz100% (3)

- Booklet Arabic Volume1Documento3 páginasBooklet Arabic Volume1njennsAún no hay calificaciones

- IADC Well Control Worksheet Surface Stack Wait and WeightDocumento3 páginasIADC Well Control Worksheet Surface Stack Wait and WeightJorge Toala100% (1)

- Re-Frac Job by HBTDocumento31 páginasRe-Frac Job by HBTEvence ChenAún no hay calificaciones