Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Practitioner Roles

Cargado por

api-200177496Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Practitioner Roles

Cargado por

api-200177496Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

Practitioner Roles

ROLES Varying job levels and positions within any organisation ranging from management to care assistant. EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION Ensuring that information is passed clearly from person to person without misunderstanding. MISSION STATEMENTS The organisations declaration of their aims and objectives for all the services they provide. BARRIERS TO ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE Anything that prevents a business running effectively e.g staff absence, poor training, lack of resources etc.

TASK

Read through each case study and then using the key words explain; 1 What should the service provide in relation to each key word? 2 Which did they fail to provide and why/how?

ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE The business and its daily set up and routines ranging from staffing and training to client care

RESPONSIBILITIES Having duties and obligations within your job role to the client and to ensure you do your job effectively. ACCOUNTABILITY Taking responsibility and account for your actions. All practitioners have a duty of care to their clients and are accountable appropriately providing it.

EFFECTIVE TEAM BUILDING Colleges working together for the good of everyone.

CASE STUDY 1 A social worker who failed to pass on details about the abuse of a toddler a week before she was murdered has been suspended for two years. Judyth Kenworthy was warned that two-year-old Sanam Navsarka had a bruise on her head and had been locked in a cupboard - but did not act. The General Social Care Council imposed the sanction after finding Ms Kenworthy guilty of misconduct. Sanam, of Huddersfield, was killed in 2008 by her mother's partner. She had more than 100 injuries. A GSCC committee said Mrs Kenworthy had been suspended from the social care register for two years. Their decision came after a conduct hearing in London. She had admitted failing to pass on a warning about the bruise on the child's head, saying she had been "extremely busy" at the time. She had also agreed that no measures were taken to safeguard Sanam as a result of her actions and admitted withholding information when she gave a statement to police. "At the very least she did not work in a safe and effective way. The public expects social care workers to be trustworthy and to work to relevant standards. "Confidence in the social care services would be undermined if they do not."

CASE STUDY 2 Twelve men and women who were taken as children from their parents and placed in care after social workers in Rochdale wrongly suspected they were victims of satanic abuse are suing the council. Around 20 children were removed from their homes by Rochdale social services in 1990 after a seven-year-old boy, Daniel Wilson, now 22, told his teachers he had been dreaming of ghosts. Social services were called and, alert to satanic "indicators" after a spate of cases in the US, thought they had uncovered a group of ritual devil worshippers. Accusations levelled against the victims' parents included claims that their children had been given hallucinogenic drugs, forced into ritualistic sex and locked in cages. Social workers also believed that newborn babies had been sacrificed in rituals. Children were subsequently taken from their parents, subject to lengthy interviews and relocated in children's homes for between three months and 10 years. Most were released in early 1991, after a court ruling that social services investigations were flawed and the subsequent allegations were untrue. Police searched the family's house for satanic apparatus, but found nothing. The Herstells' then 10-year-old daughter, Lisa, one of the claimants, was held at a children's home for more than five months. The legal action, expected to reach court later this year, coincides with last night's BBC1 documentary on the case, after the BBC successfully challenged an injunction in the high court that prohibited the victims from speaking about their ordeal. The programme makers were also granted permission to reveal the names of two social workers, Susan Hammersley, 43, and team leader Jill France, 50, who were at the centre of the Rochdale case. Both still work in child protection. In a statement, Rochdale council said: "[We have] both acknowledged and apologised for the errors made in the investigation of the allegations in the 1991 case."

Daniel has only hazy memories of the day that his childhood effectively ended. He vaguely recalls, at the age of 6, being tak en to the head teachers office at school, of strangers arriving and taking him away in a car. He remembers sitting in a small room filled with toys as a social worker asked him endless questions, of pleading for his mother but instead being taken that night to a Catholic childrens home where they put him in a bath and scrubbed him with nailbrushes. He didnt know it then, but he would not return home for another ten years. Though the details of these early events are fragmented in his mind, the memory of his tearful bewilderment and desperate longing to go home remains vivid. Today Daniel, a tall, pleasant but anxious young man of 22, is still uncomprehending and very angry. Incredibly, he was forced to live in care between the ages of 6 and 16, torn from his distraught parents, despite a judge ruling that there was no evidence that he was being abused. But that is not the worst of what happened to his family. The full story beggars belief. Thanks to the zealousness some called it obsessiveness of a handful of social workers in Rochdale, Lancashire, Daniels parents, Andrew and Beverley, were wrongly accused of involvement in a Satanic abuse network, a cult that supposedly involved ritualistic sex with minors, the slaughter of animals and the sacrifice of newborn babies. All four of their children were taken from them. Three months later, in June 1990, 12 more children, all friends of Daniel, his sister and the family, were taken from their beds in traumatic morning raids, forced to endure intimate medical examinations and placed in care for months while investigations were conducted. During this time, bizarre though it seems, parents and children were kept apart because social workers suspected that they were communicating secretly with their children via coded signals and gestures. Andrew and Beverleys other sons, James and Matthew, then 3 and 4, spent seven years in a childrens home. Their daughter Julie, then 11, spent five years in care. Andrew and Beverley were allowed to see their children for just an hour a month, monitored by social workers. Contact with Daniel was reduced gradually from an hour a month to an hour a year. Yet there was never any proof forensic, medical or otherwise to support claims of ritual abuse against any of the families, and the case remains one of the most scandalous misjudgments by a British social services department. The evidence? It was this: Daniel told his teacher that he was dreaming about ghosts apparently a mummy and daddy ghost and a baby ghost that died. He was at the time a withdrawn, disturbed child, often hiding under desks and being disruptive. His speech was poor for his age. This, says Beverley, led to him being bullied. The teacher was concerned enough to alert social services. Unfortunately for residents of the Langley council estate in Rochdale, this coincided with a particular climate in Britain in the late 1980s and early 1990s in which social workers were being trained to spot satanic indicators signs that a child was suffering ritual abuse after a spate of alleged cases in America. Social workers interpreted Daniels ghosts as being his abusers. They read his fantasies of being locked in a cage as reality evidence of satanic abuse and pursued the notion with a vigour that Professor Elizabeth Newson, an expert witness in the case, describes as unhealthy single-mindedness. Now, for the first time, Daniel, his siblings and the other children whose lives were wrecked by the scandal can speak publicly about their experience after the BBC successfully challenged a longstanding injunction that gagged them and prevented the media from identifying the two key social workers involved in the case, Jill France and Susan Hammersley. Both still work in child protection. It also obtained social services original video -recorded interviews with the children a legal precedent which can be seen in a documentary tomorrow night. One child, Caroline, then 6, is seen being so distraught throughout her interview that the judge said it was one of the mos t abiding and disturbing parts of the case. As many of those children, now adults, say, the only abuse they suffered was at the hands of the authorities.

When I meet Daniel, he is in his parents house (they still live on the same estate), drinking tea and struggling for words t o describe how those lost years have scarred him. He finds talking about his fractured upbringing harrowing and there is a palpable air of sadness about him. I lack the confidence that everyone else seems to have, he says. I find it hard to strike up conversations with people. Ive missed such a lot. How would he describe his childhood in care? Unhappy. The first time Daniel heard that suspected satanic abuse and his dreams were at the root of his familys nightmare was when he was 16 and left foster care to return to his mother. He had spent ten years in a fog of uncertainty, never told the specifics of the case or allowed to read newspaper reports of it. I couldnt believe it, he says. At the time I didnt understand what was happening. I had no idea. I kept asking if I coul d go back home and they just said No, its not safe for you, they didnt explain more than that. I didnt believe it but they are in control of you, theres nothing you can do. But I always wanted to go home. Always. His social workers were not even consistent in their explanations. When he was about 12, Daniel, still totally in the dark, asked a social worker why he was in care. I remember her saying that it was because of me, he says. Nothing else, just that. It was a particularly cruel statement, given a childs propensity to f eel responsible for problems in the family. He and Julie were placed in one childrens home, James and Matthew in another. Julie, now 26 and a carer in a nursing home, r ecalls social workers refusing to let them take any toys or clothes from home. They took the clothes we were wearing and threw them away, she says. Id got a new coat for my birthday and they put it in the b in, saying it was filthy. When police raided the house they took as evidence a cross that Julie had made from two lollipop stic ks, and a religious wall plaque that she had given her mother, portraying Jesus on the Cross, which bore the words God bless our home and featured a small well for holy water. It was later alleged that this had been used to hold blood. It is still on the familys wall. Julie winces at the memory of the medical examination she underwent in hospital to determine whether she had been sexually abused (it was negative). I felt sick. Invaded, she says. She, too, had no inkling of the satanic abuse allegations and wasnt told why she was being examined. After a few years in the childrens home Daniel and Julie went to a foster home in Stockport until, unable to bear it any lon ger, she walked out at 16 and went home to her parents. It felt, she says, the most right and natural thing in the world. But she still feels the stigma following her. Being a kid in care is hard, she says. When people at school asked why I was with foster parents Id just say that my real parents were ill. It makes you wonder about the way people look at you, what they think about you. Im still not as confident as I should be; I tend to keep myself to myself. I dont know if well ever get over it. They were by no means the only family to be broken by the so-called satanic panic. David, 13-year-old brother of the traumatised Caroline, says he will never forget the horror of being dragged out of his bed at 7.30am, while his distraught father was held back by police, just because they were friendly neighbours of Daniels family. Or, when he finally came home after two months, of being called devilworshipper in the street and his friends being banned from playing with him.

Now a 29-year-old HGV driver and father of three, he still gets butterflies in his stomach when he recalls the interviews in which he was asked to name the genitals on a naked doll. Like all the children he steadfastly denied that he was being abused but his interviewers seemed reluctant to believe it. At one point on the tapes he asks the social worker Why dont you listen to us like it says on the (NSPCC) posters? The children are now pursuing a civil action against Rochdale Council for the trauma they suffered and may receive thousands in compensation. But, as David says: It was hard for the kids but I think it was probably even harder for the parents. Shit sticks. They had to walk the streets being shouted at and read all that stuff in the papers. Andrew and Beverley certainly felt persecuted. It must be said at the outset that they were not perfect parents. Beverley was a young mother, having Julie when she was just 16, and she was extremely poor. By the time three more babies arrived the authorities, while accepting that the couple loved their children, said that they couldnt look after them very well. So for four years they attended weekly parenting classes run by the National Children s Home, learning about nutrition and how to manage their finances. They even confided to the NCH the problems with Daniels ghost fixation and behaviour at mealtimes he would kick off and crawl into cupboards and were assured that he would grow out of it. Julie remembers that at around that time the children had watched the film Ghostbusters and it had stuck in our heads. Daniel was always a joker, she says, smiling. It also emerged, however, that he had been allowed to watch horror films, despite his age. But when the satanic abuse case collapsed a year after the children were taken, Beverley and Andrews children were the only ones not to return home. Social workers changed tack, saying that the children were neglected and unkempt and should remain in care, despite them all begging to go home. Andrew and Beverley were told that the children were settling in their new lives and that it would be disruptive and unhelpful for them to see too much of their parents but the children say that this wasnt true. Matthew and James were even put up for adoption, their photographs appearing in a social services magazine, although, to Andrew a nd Beverleys eternal relief, no one took them. According to the notes, the neglect seemed to consist of relatively trivial things such as poor discipline and giving the children sweets befo re bed. Much was made of the couples debts, which Tony Heaford, a local councillor who took up their case, described as penalisation of the poor. It felt as though both my arms had been ripped out, says Beverley, 43. In one day they had all just gone. There was nothing I could do. Whatever (we) did was wrong, whatever (we) said was wrong as far as social services were concerned. If I wanted to know anything (about the children) I had to be nice and polite to them or they would say we were being difficult. Every month they faced the unimaginable torture of having to say goodbye to their weeping, clinging children. On one visit Julie screamed and clung to her mother so tightly that a nun from the home had to prise her off. That broke me, she says. Their rights as parents seemed to count for little. Andrew says that they could never see their children on Christmas Day because they had to make their own way there and no buses were running, so for years they had a makeshift festive celebration on December 20 as social workers watched from behind a mirror. It was the same with birthdays they could never see the children on the day, only after the event. They had to beg for privileges such as a school photograph. Any letters and cards had to be sent via the social workers. The nights were the worst, says Beverley. I would just lie there, missing them. I couldnt sleep. For ages I was still making tea for six people. I didnt touch their bedrooms for months. I kept thinking Theyll be back soon, theyll be back soon but I was wrong. Elizabeth Newson, a professor of developmental psychology, was drafted in as an expert witness for the court case. She quickly noted the poor standards of the social workers interviews and observations, the wa y they interpreted dreams as reality. The crucial first interview with Daniel, in which he was alleged to have made long statements about ghosts, was not videotaped.

The judge did accept that the social workers were motivated by zeal rather than malice, saying: I do not question the good f aith or good intentions of the social workers, who I acknowledge were working under considerable pressure. But Professor Newson believes that they were obsessional and had convinced themselves that the ritual abuse was happening. I thought there

was another ingredient to this as well as concern for the children, she says. There was an unhealthy excitement about it which we also saw in Cleveland (another notorious child abuse case) . . . They had begun to believe that they were experts.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s there were 80 alleged cases of satanic abuse in Britain, including the infamous Orkneys case, but not one was ever proved. Parents in Rochdale claim that they were told untruths, including that their children were settling down well with foster parents when actually they were pleading to go home. The social workers were adding to the childrens powerlessness, says Professor Newson. Ironically, Beverley was relieved when they first questioned Daniel. She assumed that it was to do with him be ing bullied and welcomed the intervention. He wouldnt even get dressed for school; I had to drag him there, crying, once, she says. The couple had brushed off his ghost talk. With Daniel it wasnt so much a fear of ghosts as chit -chat. He would hide behind doors and jump out on you, saying that ghosts were behind him. He loved it when you said Ooh, Daniel, you frightened me. It was his favourite game. Now, although she smiles as she remembers the elation when the family were all finally back together again it was like a jigsaw puzzle being finished she doubts that their scars will ever heal. All of them suffer from anxiety. James cannot work because of his depression; Daniel, who has a baby son of his own, also does not work. Ive got four kids but Ive never brought any of them up from nought to a teenager, says Beverley. The bit in the middle is missing and I cant ever get it back. Ive missed little things like James and Matthew getting their first teeth, Julie getting her first boyfriend, holidays together. All we want is for them to say sorry to us and to learn from their mistakes so that it doesn t happen again. Considering the way that this family was treated by the system, it seems precious little to ask. ROCHDALES RESPONSE Terry Piggott, Rochdale Councils executive director responsible for children, schools and families, said of the BBCs documentary: The council was invited to take part in the programme some months ago but declined to do so on legal advice, taking into account the civil action for damages currently being pursued against the council by some of the children (now adults) involved in the case. The council has, however, provided a statement of its position to the BBC to be used as part of the programme. I cannot see how the interests of todays challenges of protecting children will be served by re-examining past cases that are 15 years old. The business of investigating allegations of child abuse can be highly traumatic for all those involved and recent cases sho w that terrible harm is being caused to children both through deliberate abuse and neglect. Society needs able and committed social workers to protect children, and media coverage that makes the recruitment of them even more difficult than it is already should be a concern for all of us. Mr Piggott has not seen the programme. Rochdale Council did not challenge the findings of the 1991 court case and, at the time, said that it had publicly both acknowledged and apologised for the errors made in the investigation of the allegations in this case. The local authority recognised the painful and traumatic experience of all the families involved. The council emphasised: Following the judgment the local authority took immediate steps to ensure that the mistakes that were made in this case would not be repeated.

WWW.TIMESONLINE.COM

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/real_story/4602302.stm

También podría gustarte

- Gce Health and Social Care Assignment Brief Unit 2 Communication and ValuesDocumento5 páginasGce Health and Social Care Assignment Brief Unit 2 Communication and Valuesapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ab Unit 21Documento9 páginasAb Unit 21api-20017749650% (2)

- FSMQ Additional Mathematics Revision NotesDocumento84 páginasFSMQ Additional Mathematics Revision Notesapi-200177496100% (2)

- Briefer Brief For 2015 16Documento38 páginasBriefer Brief For 2015 16api-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- 8 AbDocumento2 páginas8 Abapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

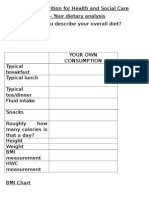

- Nutritional AnalysisDocumento4 páginasNutritional Analysisapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Gce H S Unit 5 AbDocumento2 páginasGce H S Unit 5 Abapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- GenderDocumento3 páginasGenderapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Geographical Location - Miss DobsonDocumento3 páginasGeographical Location - Miss Dobsonapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Individual CircumstancesDocumento3 páginasIndividual Circumstancesapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- EthnicityDocumento3 páginasEthnicityapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- p3 4 Writing FrameDocumento4 páginasp3 4 Writing Frameapi-20017749680% (5)

- UNIT 7 Sociological Perspectives-P3 Homework Task Health and Illness Issue - AGE Life ExpectancyDocumento3 páginasUNIT 7 Sociological Perspectives-P3 Homework Task Health and Illness Issue - AGE Life Expectancyapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mathswatch Foundation AnswersDocumento134 páginasMathswatch Foundation Answersapi-20017749648% (21)

- Evalution TipsDocumento1 páginaEvalution Tipsapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mathswatch Higher AnswersDocumento141 páginasMathswatch Higher Answersapi-20017749636% (14)

- Starter-10 Minutes To Prepare Your Data To Share With The Rest of The ClassDocumento1 páginaStarter-10 Minutes To Prepare Your Data To Share With The Rest of The Classapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Perspectives of Health InequalitiesDocumento24 páginasPerspectives of Health Inequalitiesapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- p2 Unit 2Documento2 páginasp2 Unit 2api-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mathswatch F and H WorksheetsDocumento185 páginasMathswatch F and H Worksheetsapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Embedding ResearchDocumento1 páginaEmbedding Researchapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Analysis HelpsheetDocumento1 páginaAnalysis Helpsheetapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ab 2Documento5 páginasAb 2api-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- p1 Writing FrameDocumento3 páginasp1 Writing Frameapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ab Unit 1 LoaDocumento3 páginasAb Unit 1 Loaapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- 8 - Consolidating Learning TeacherDocumento1 página8 - Consolidating Learning Teacherapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ab Unit 2 LobDocumento2 páginasAb Unit 2 Lobapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- Care Values WorksheetDocumento5 páginasCare Values Worksheetapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- 1 - Concepts of Health p2Documento39 páginas1 - Concepts of Health p2api-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- 7 - The New Right SamDocumento10 páginas7 - The New Right Samapi-200177496Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2102)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Gonzales v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L-37453, (May 25, 1979), 179 PHIL 149-177)Documento21 páginasGonzales v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L-37453, (May 25, 1979), 179 PHIL 149-177)yasuren2Aún no hay calificaciones

- BBS of Lintel Beam - Bar Bending Schedule of Lintel BeamDocumento5 páginasBBS of Lintel Beam - Bar Bending Schedule of Lintel BeamfelixAún no hay calificaciones

- Philsa International Placement and Services Corporation vs. Secretary of Labor and Employment PDFDocumento20 páginasPhilsa International Placement and Services Corporation vs. Secretary of Labor and Employment PDFKrissaAún no hay calificaciones

- Guide To Tanzania Taxation SystemDocumento3 páginasGuide To Tanzania Taxation Systemhima100% (1)

- Precontraint 502S2 & 702S2Documento1 páginaPrecontraint 502S2 & 702S2Muhammad Najam AbbasAún no hay calificaciones

- SANTHOSH RAJ DISSERTATION Presentation1Documento11 páginasSANTHOSH RAJ DISSERTATION Presentation1santhosh rajAún no hay calificaciones

- Listen The Song and Order The LyricsDocumento6 páginasListen The Song and Order The LyricsE-Eliseo Surum-iAún no hay calificaciones

- Art CriticismDocumento3 páginasArt CriticismVallerie ServanoAún no hay calificaciones

- PhonemeDocumento4 páginasPhonemealialim83Aún no hay calificaciones

- JawabanDocumento12 páginasJawabanKevin FebrianAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Curriculum Guides Agricultural ScienceDocumento52 páginas1 Curriculum Guides Agricultural ScienceDele AwodeleAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Papers Harvard Business SchoolDocumento8 páginasResearch Papers Harvard Business Schoolyquyxsund100% (1)

- 34 The Aby Standard - CoatDocumento5 páginas34 The Aby Standard - CoatMustolih MusAún no hay calificaciones

- Computer Education in Schools Plays Important Role in Students Career Development. ItDocumento5 páginasComputer Education in Schools Plays Important Role in Students Career Development. ItEldho GeorgeAún no hay calificaciones

- TWC AnswersDocumento169 páginasTWC AnswersAmanda StraderAún no hay calificaciones

- Gaffney S Business ContactsDocumento6 páginasGaffney S Business ContactsSara Mitchell Mitchell100% (1)

- Upvc CrusherDocumento28 páginasUpvc Crushermaes fakeAún no hay calificaciones

- Bethany Pinnock - Denture Care Instructions PamphletDocumento2 páginasBethany Pinnock - Denture Care Instructions PamphletBethany PinnockAún no hay calificaciones

- The Constitution Con by Michael TsarionDocumento32 páginasThe Constitution Con by Michael Tsarionsilent_weeper100% (1)

- CT, PT, IVT, Current Transformer, Potential Transformer, Distribution Boxes, LT Distribution BoxesDocumento2 páginasCT, PT, IVT, Current Transformer, Potential Transformer, Distribution Boxes, LT Distribution BoxesSharafatAún no hay calificaciones

- Ks3 English 2009 Reading Answer BookletDocumento12 páginasKs3 English 2009 Reading Answer BookletHossamAún no hay calificaciones

- Alliance Manchester Business SchoolDocumento14 páginasAlliance Manchester Business SchoolMunkbileg MunkhtsengelAún no hay calificaciones

- Corporation True or FalseDocumento2 páginasCorporation True or FalseAllyza Magtibay50% (2)

- Cone Penetration Test (CPT) Interpretation: InputDocumento5 páginasCone Penetration Test (CPT) Interpretation: Inputstephanie andriamanalinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Tutorial Inteligencia Artificial by MegamugenteamDocumento5 páginasTutorial Inteligencia Artificial by MegamugenteamVictor Octavio Sanchez CoriaAún no hay calificaciones

- 4.2 Master Schedule - ACMP 4.0, Summar 2020 - 28 Aug 2020Documento16 páginas4.2 Master Schedule - ACMP 4.0, Summar 2020 - 28 Aug 2020Moon Sadia DiptheeAún no hay calificaciones

- Eris User ManualDocumento8 páginasEris User ManualcasaleiroAún no hay calificaciones

- MoncadaDocumento3 páginasMoncadaKimiko SyAún no hay calificaciones

- THE THIRD TEST - No AnswersDocumento11 páginasTHE THIRD TEST - No Answersdniela .fdrsairAún no hay calificaciones

- CerinaDocumento13 páginasCerinajoe 02Aún no hay calificaciones