Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The Narrative of John Smith

Cargado por

yollacullenDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Narrative of John Smith

Cargado por

yollacullenCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Before there was the astute detective Sherlock Holmes and his capable compatriot Watson, there was

the opinionated Everyman John Smith. In 1883, when he was just twenty-three, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote The Narrative of John Smith while he was living in Portsmouth and struggling to establish himself as both a doctor and a writer. He had already succeeded in having a number of short stories published in leading magazines of the day, such as Blackwoods, All the Year Round, London Society, and the Boys Own Paperbut as was the accepted practice of literary journals of the time, his stories had been published anonymously. Thus, Conan Doyle knew that in order to truly establish his name as a writer, he would have to write a novel. That novelthe first he ever wrote and only now published for the first time is The Narrative of John Smith.

Many of the themes and stylistic tropes of his later writing, including his first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarletpublished in 1887can be clearly seen. More a series of ruminations than a traditional novel, The Narrative of John Smith is of considerable biographical importance and provides an exceptional window into the mind of the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Through John Smith, a fifty-year-old man confined to his room by an attack of gout, Conan Doyle sets down his thoughts and opinions on a range of subjects including literature, science, religion, war, and educationwith no detectable insecurity or diffidence. His writing is full of bravado.

Though unfinished, The Narrative of John Smith stands as a fascinating record of the early work of a man on his way to being one of the best-known authors in the world. This book will be welcomed with enthusiasm by the numerous Conan Doyle devotees.

Arthur Conan Doyle's first novel, written in 1883 and lost in the mail on its way to the publisher (the uncompleted text we have was rewritten from memory), The Narrative of John Smith was first published in 2010 by the British Library, which acquired the manuscript in 2004. The edition was edited and introduced by Jon Lellenberg, Daniel Stashower, and Rachel Foss, who provide a very good background essay and a series of explanatory annotations to show how ideas, concepts and even specific turns of phrase

first deployed here find their way into Conan Doyle's later, better-known writings.

The narrative itself is less than exciting; a middle-aged man, confined to his room for a week by gout, engages in a series of ruminations and descriptions: he provides a minute tour of his room and its furnishings, muses on the neighbors across the street and those who share his building, and discourses (mostly with himself, but occasionally with his visiting doctor) on all manner of topics. Not a whole lot happens, and the fragmentary nature of the rewritten text prevents much narrative flow from getting underway. Not to mention, of course, the fact that the novel remains unfinished.

But, there are diamonds in this rough: the style that those of us who enjoy Conan Doyle's stories know and love shines through in more than a few places. Some of those I noted particularly:

- describing the lot of a young writer: "The articles which I sent forth came back to me at times with a rapidity and accuracy which spoke well for our postal arrangements. If they had been paper boomerangs they could not have returned more infallibly to their unhappy dispatcher" (p. 29)

- on books: "There should be a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Books. I hate to see the poor patient things knocked about and disfigured. A book is a mummifed soul embalmed in morocco leather and printer's ink instead of cerecloths and unguents. It is the concentrated essence of a man. Poor Horatius Flaccus has turned to an impalpable power by this time, but there is his very sprit stuck like a fly in amber, in that brown-backed volume in the corner. A line of books should make a man subdued and reverent. If he cannot learn to treat them with becoming decency he should be forced" (p. 19)

- a tour round his flat: "And then the knick-knacks! Those are the things which give the individuality to a room - the flotsam and jetsam which a man picks up carelessly at first, but which soon drift into his heart. If it conduces

to comfort to have these little keepsakes of the past before one's eyes, then what matter how inelegant they may chance to be!" (p. 17)

Certainly worth reading for the insight it offers into the author's early style. But make sure to read the notes as you go along; they're a key part of the work, and the editors have done a fine job with them.

También podría gustarte

- A Shocking Accident - Graham GreeneDocumento5 páginasA Shocking Accident - Graham GreenelluneraAún no hay calificaciones

- Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the 1920s and 1930sDe EverandShores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the 1920s and 1930sCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (16)

- The Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950-1965De EverandThe Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950-1965Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (8)

- The Devils and Canon Barham: Ten Essays On Poets, Novelists and MonstersDe EverandThe Devils and Canon Barham: Ten Essays On Poets, Novelists and MonstersCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (3)

- The Circus, and Other Essays and Fugitive PiecesDe EverandThe Circus, and Other Essays and Fugitive PiecesAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes: Classic Stories (Barnes & Noble Collectible Editions)De EverandSherlock Holmes: Classic Stories (Barnes & Noble Collectible Editions)Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Daily Sherlock Holmes: A Year of Quotes from the Case-Book of the World’s Greatest DetectiveDe EverandThe Daily Sherlock Holmes: A Year of Quotes from the Case-Book of the World’s Greatest DetectiveCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2)

- The Hidden Holmes: A Serious Rereading of the Stories and Novels by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with Analyses and CommentaryDe EverandThe Hidden Holmes: A Serious Rereading of the Stories and Novels by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with Analyses and CommentaryAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes Great War Parodies and Pastiches I: 1910-1914De EverandSherlock Holmes Great War Parodies and Pastiches I: 1910-1914Aún no hay calificaciones

- On Conan Doyle: Or, The Whole Art of StorytellingDe EverandOn Conan Doyle: Or, The Whole Art of StorytellingCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (50)

- Literature in the Making, by Some of Its MakersDe EverandLiterature in the Making, by Some of Its MakersAún no hay calificaciones

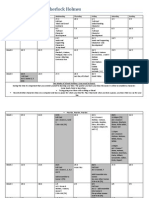

- Sotheby's Catalog Excerpt - Inscribed Edition of A Study in ScarletDocumento5 páginasSotheby's Catalog Excerpt - Inscribed Edition of A Study in ScarletScott MontyAún no hay calificaciones

- Victorian Literature (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)De EverandVictorian Literature (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Rogues: A Scandalous History of Wayward AuthorsDe EverandLiterary Rogues: A Scandalous History of Wayward AuthorsCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (24)

- Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920sDe EverandClassic American Crime Fiction of the 1920sCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Delphi Works of George Bernard Shaw (Illustrated)De EverandDelphi Works of George Bernard Shaw (Illustrated)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Steven Moore - The Novel - An Alternative History - Beginnings To 1600 (2013)Documento1205 páginasSteven Moore - The Novel - An Alternative History - Beginnings To 1600 (2013)Fer100% (3)

- The Millionaire and the Bard: Henry Folger's Obsessive Hunt for Shakespeare's First FolioDe EverandThe Millionaire and the Bard: Henry Folger's Obsessive Hunt for Shakespeare's First FolioCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (8)

- The World's Smartest Detectives: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; Martin Hewitt, Investigator; The Old Man in the Corner; and The Thinking MachineDe EverandThe World's Smartest Detectives: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; Martin Hewitt, Investigator; The Old Man in the Corner; and The Thinking MachineAún no hay calificaciones

- 1235 - Heart of Darkness Critical NotesDocumento2 páginas1235 - Heart of Darkness Critical NotesSumayyah Arslan100% (1)

- Krystal, Arthur - Easy WritersDocumento7 páginasKrystal, Arthur - Easy WritersMiroslav Curcic100% (1)

- George Steiner, The Art of Criticism No. 2: Interviewed by Ronald A. SharpDocumento55 páginasGeorge Steiner, The Art of Criticism No. 2: Interviewed by Ronald A. SharpArdit Kraja100% (1)

- Don QuixoteDocumento1 páginaDon QuixotedenisAún no hay calificaciones

- CharacterDocumento4 páginasCharacterAndreaAún no hay calificaciones

- Novel 2Documento21 páginasNovel 2Sara SwaraAún no hay calificaciones

- Types of NovelsDocumento6 páginasTypes of NovelsRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamAún no hay calificaciones

- English Novels Note 3Documento6 páginasEnglish Novels Note 3roxAún no hay calificaciones

- Interview With Philip KitcherDocumento11 páginasInterview With Philip Kitcherartosk8100% (1)

- Handout English LiteratureDocumento7 páginasHandout English LiteratureAlina Georgia MarinAún no hay calificaciones

- Written Lives - Javier MariasDocumento125 páginasWritten Lives - Javier MariasEduardo ArauAún no hay calificaciones

- Holiday Homework - XiDocumento5 páginasHoliday Homework - Xiarmyinsane1Aún no hay calificaciones

- In Defense of The Canon - Arthur KrystalDocumento5 páginasIn Defense of The Canon - Arthur KrystalStephen GarrettAún no hay calificaciones

- Borges Jorge Luis A Universal History of Infamy Penguin 1975 PDFDocumento138 páginasBorges Jorge Luis A Universal History of Infamy Penguin 1975 PDFRupai Sarkar100% (1)

- Ecstasies and Odysseys: The Weird Poetry of Donald WandreiDocumento21 páginasEcstasies and Odysseys: The Weird Poetry of Donald WandreiLeigh Blackmore50% (2)

- English Novel Since 1950Documento13 páginasEnglish Novel Since 1950Andrew YanAún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Art in An Age of Formula Fiction and Mass Consumption: Double Coding in Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Blue Carbuncle"Documento16 páginasLiterary Art in An Age of Formula Fiction and Mass Consumption: Double Coding in Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Blue Carbuncle"AnanyaRoyPratiharAún no hay calificaciones

- Balzac: The Greatest Novelist of Them All?Documento17 páginasBalzac: The Greatest Novelist of Them All?Christopher GuerinAún no hay calificaciones

- Jess308 PDFDocumento12 páginasJess308 PDFRajat SabharwalAún no hay calificaciones

- 19th CenturyDocumento8 páginas19th CenturyRaquel GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Romantic Latin Quotes and PhrasesDocumento2 páginasRomantic Latin Quotes and PhrasesyollacullenAún no hay calificaciones

- Romantic Latin Quotes and PhrasesDocumento2 páginasRomantic Latin Quotes and PhrasesyollacullenAún no hay calificaciones

- Alberto Manguel CitateDocumento18 páginasAlberto Manguel CitateyollacullenAún no hay calificaciones

- Michelangelo Buonarroti PoemsDocumento5 páginasMichelangelo Buonarroti PoemsyollacullenAún no hay calificaciones

- Elizabethan TheatreDocumento27 páginasElizabethan TheatreyollacullenAún no hay calificaciones

- Bram Stoker - DraculaDocumento346 páginasBram Stoker - DraculaxhopinAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock HolmesDocumento16 páginasSherlock HolmesLorenzo Stefano Fachinetti TorresAún no hay calificaciones

- MorDocumento2 páginasMorGit GitaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Boscombe Valley MysteryDocumento1 páginaThe Boscombe Valley MysteryIva SivarajaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Speckled Band ResumenDocumento2 páginasThe Speckled Band ResumenMi ScrAún no hay calificaciones

- Tugas Bahasa InggrisDocumento2 páginasTugas Bahasa InggrisLuckyta Citra Ayu ParamithaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes The Norwood MysteryDocumento24 páginasSherlock Holmes The Norwood MysteryLa Princesa De Cristian50% (2)

- Reader.2 The Last Sherlock Home StoryDocumento2 páginasReader.2 The Last Sherlock Home StoryEstrellaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock HolmesDocumento2 páginasSherlock HolmesEvrydiki GkoriAún no hay calificaciones

- Too Sign of 4Documento22 páginasToo Sign of 4rohit koyandeAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes Short Stories: Sir Arthur Conan DoyleDocumento4 páginasSherlock Holmes Short Stories: Sir Arthur Conan DoyleLearn EnglishAún no hay calificaciones

- The Characters: Sherlock HolmesDocumento18 páginasThe Characters: Sherlock HolmesMark TaysonAún no hay calificaciones

- AK-Sherlock Holmes Boscombe PoolDocumento2 páginasAK-Sherlock Holmes Boscombe PoolVeronica Villalva50% (2)

- Rehearsal Schedule FINAL 2Documento5 páginasRehearsal Schedule FINAL 2Edwin ChaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading Comprehension Sherlock Holmes, The World's Best-Known DetectiveDocumento6 páginasReading Comprehension Sherlock Holmes, The World's Best-Known DetectiveEvelyn GualdronAún no hay calificaciones

- BSI Oral History ProjectDocumento36 páginasBSI Oral History ProjectRavi JanakiramanAún no hay calificaciones

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocumento6 páginasRhetorical Analysisapi-262751160Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Notorious Canary Trainers: Check Your Name Below Contact Information Changes? Use Back If NeededDocumento1 páginaThe Notorious Canary Trainers: Check Your Name Below Contact Information Changes? Use Back If Neededapi-42860685Aún no hay calificaciones

- Duty of Reading Chapter 5Documento2 páginasDuty of Reading Chapter 5Mass Dittya SangKsatria GarudaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Arthur Conan DoyleDocumento162 páginasThe Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Arthur Conan DoyleDaffodilAún no hay calificaciones

- The Boscombe Valley Mystery STDDocumento11 páginasThe Boscombe Valley Mystery STDkaveesh_93Aún no hay calificaciones

- 10th English Slow Learners Study Materials English Medium PDF DownloadDocumento3 páginas10th English Slow Learners Study Materials English Medium PDF DownloadDharuman MAún no hay calificaciones

- Book Report I, Report 3Documento2 páginasBook Report I, Report 3CV Putera Pandega PupaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Hound of The Baskervilles Chapter 1Documento5 páginasThe Hound of The Baskervilles Chapter 1Jean Claire LlemitAún no hay calificaciones

- The Adventure of The Abbey GrangeDocumento20 páginasThe Adventure of The Abbey GrangemoisesAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes Level5 PenguinDocumento135 páginasSherlock Holmes Level5 PenguinHammad Raza100% (8)

- MacmillanDocumento1 páginaMacmillanantonn85Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Adventure of Speckled BandDocumento2 páginasThe Adventure of Speckled BandMeha SakariyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Transcript - I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere Episode 203: The Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes PodcastDocumento40 páginasTranscript - I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere Episode 203: The Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes PodcastScott MontyAún no hay calificaciones

- Sherlock Holmes Is Over 130: Cape "ElementaryDocumento4 páginasSherlock Holmes Is Over 130: Cape "ElementaryFrancisco RiveraAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Appearance Personality Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form 93999Documento2 páginasPhysical Appearance Personality Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form 93999Shihab Ameen AL-saidiAún no hay calificaciones